TWENTY-THREE

Ceratopsidae

Ceratopsids, or horned dinosaurs, comprise a monophyletic assemblage of large-bodied (4-8 m long), quadrupedal, herbivorous ornithischians. Easily recognized by their varied and elaborate horn and frill morphologies, as well as their hypertrophied narial regions and complex dental batteries, ceratopsids possess some of the largest, most elaborated skulls found among vertebrates. Indeed, skulls of certain taxa (e.g., Torosaurus and Pentaceratops) reached lengths greater than 2 m, the largest known for any terrestrial vertebrate (Colbert and Bump 1947; Lehman 1998). Ceratopsidae consists of two well-defined clades: Centrosaurinae and Chasmosaurinae. Although some genera and species are represented by single, incomplete individuals (e.g., Arrhinoceratops, Diceratops), many others consist of numerous nearly complete skulls and skeletons (e.g., Chasmosaurus, Centrosaurus). Intact skeletons are less common than skulls, and several ceratopsids have no reliably associated postcranials (e.g., Arrhinoceratops, Diceratops). In addition to numerous isolated materials, ceratopsids were also regularly preserved in large, low-diversity mass death assemblages, or bone beds.

Among the first ceratopsid taxa to be described were Agathaumas Cope 1872, Polyonax Cope 1874, Dysganus Cope 1876a, and Monoclonius Cope 1876a. All of these forms were based on incomplete materials from which no concept of ceratopsians could be derived. In fact, Marsh (1887a) named one of the first Triceratops “Bison alticornis,” because he imagined that the enormous horn-core belonged to an extinct bovid. The first complete ceratopsian cranial material was that of Triceratops (Marsh 1889b). New ceratopsids are still being discovered—two new taxa, Einiosaurus procurvicornis and Achelousaurus horneri, were described in 1995 (Sampson 1995), and a new species of Chasmosaurus—C. irvinensis—was named in 2001 (Holmes et al. 2001). The first comprehensive study of ceratopsids was that of Hatcher et al. (1907). At that time, complete skulls were known only for Triceratops and Torosaurus; nevertheless, that 1907 monograph remains the most valuable single reference on ceratopsid anatomy.

Ceratopsids were a highly successful group (table 23.1). They form 25%-42% of the individuals in the Campanian dinosaur communities in which they occur, subordinate in this category only to hadrosaurids (Dodson 1983, 1987; Lehman 1997; D. B. Brinkman et al. 1998). Similarly, they make up 61%-71% of the terminal Cretaceous communities, although at much reduced diversity (e.g., Triceratops, Torosaurus, Lehman 1987; White et al. 1998). The time and location of the origin of ceratopsids from more basal neoceratopsians has been enigmatic due to a paucity of relevant fossil data. The recent discovery of a Turonian-age ceratopsian, Zuniceratops (Wolfe and Kirkland 1998), provides some insights into this matter. In addition to its early occurrence, Zuniceratops possesses characters previously thought to be restricted to Ceratopsidae, and thus provides crucial evidence for character evolution toward ceratopsids. Nevertheless, ceratopsids comprise an evolutionary radiation that diversified into a broad array of species over a geologically brief period during the Late Cretaceous (Campanian and Maastrichtian). The group is also restricted geographically, known only from western North America (United States, Canada, Mexico), with their remains preserved primarily along the western shores of the inland sea. They ranged from the North Slope of Alaska (Parrish et al. 1987) and the Northwest Territories (Russell 1984c), at paleolatitudes as high as 85° N (Brouwers et al. 1987), down south as far as Mexico (Murray et al. 1960; Ferrusquia-Villafranca 1998). To date, reports of ceratopsids outside of western North America cannot be confirmed; isolated horns from Asia have been claimed to be ceratopsid but are more plausibly interpreted as ankylosaurian (Coombs 1987). Until recently, it was thought that chasmosaurines were more widely distributed than centrosaurines. However, remains of at least one centrosaurine genus (Pachyrhinosaurus) have been found in Alaska (Rich et al. 1997), and Williamson (1997) provided unequivocal evidence of an early Campanian centrosaurine from the Menefee Formation of New Mexico.

Definition and Diagnosis

We define Ceratopsidae as the clade consisting of Centrosaurus and Triceratops and their most recent common ancestor and all of its descendants. Ceratopsids are derived in many aspects of their bony anatomy, particularly the skull. Characters diagnosing Ceratopsidae include: greatly enlarged external nares, prominent premaxillary septum, antorbital fenestra greatly reduced in size, presence of a nasal horn-core, reduced lacrimal, frontal eliminated from the orbital margin, dentary articulation set well below the alveolar margin, the basioccipital excluded from the foramen magnum, the supraoccipital eliminated from the foramen magnum, the marginal undulations on the frill augmented by epoccipitals, the tooth row extending caudal to the coronoid process, laterally stacked quadrate-quadratojugal-jugal, presence of a shallow supracranial cavity complex, an elongate groove on the squamosal to receive the quadrate, the largest dimension of parietal fenestra oriented axially, olfactory tract exits surrounded by interorbital ossifications, number of exits for c.nn. X, XI, XII reduced to two, more than two replacement teeth in each vertical series, loss of subsidiary ridges on teeth, teeth with two roots, atlantal neural arch steeply inclined caudally, ten or more sacral vertebrae, sternum short and broad, laterally everted shelf on the dorsal rim of the ilium, presence of a supracetabular process (“antitrochanter”), the ischium gently to greatly decurved, the greater and cranial trochanters fused together on the femur, the femur longer than the tibia, and hooflike pedal unguals.

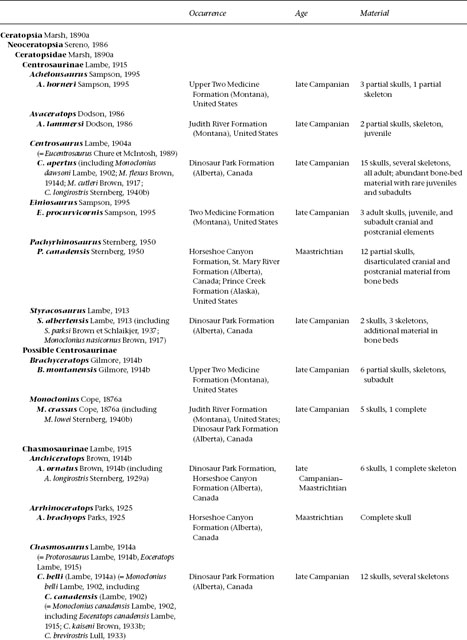

TABLE 23.1

Ceratopsidae

Anatomy

Skull and Mandible

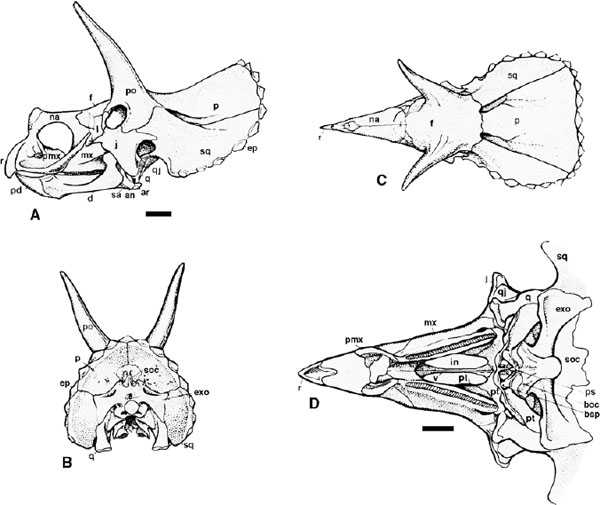

The skulls of ceratopsids (figs. 23.1–23.4) are broadly triangular in dorsal view, flaring widely across the jugals and tapering rostrally to a narrow, keeled, edentulous beak. A prominent parietosquamosal frill characterizes all taxa. A deep face is also characteristic, and the tall premaxilla, with a greatly enlarged external naris, occupies much of this height. The rostral has a rugose texture and may have been covered by a horny sheath in life. Its ventral cutting edge is thin and beveled. The rostral fuses to the premaxilla only in mature individuals and is frequently not preserved in juveniles and young adults. The specific shape of the rostral differs between chasmosaurines and centrosaurines: that of centrosaurines is nearly triangular in lateral view with short dorsal and caudal processes, whereas that of chasmosaurines is much more elongate, with a greatly decurved rostral “beak.” The rostral opposes the more elongate predentary, which terminates in a sharp, upcurved point that rests inside the rostral. The predentary is robust and the cutting edge, which is thick and flat, is nearly horizontal in chasmosaurines but strongly sloped laterally in centrosaurines (Forster 1990b; Lehman 1990). The caudodorsal process of the predentary is elongate compared to that of basal ceratopsians and is subequal in size to the caudoventral process.

The premaxilla is one of the most prominent elements of the facial skeleton and may nearly equal the maxilla in length. The external naris is greatly enlarged and usually subcircular in shape. The premaxillae lie directly appressed to each other for their entire rostral half, forming an extensive, deep septum directly in front of the external naris. In centrosaurines, this septum is flat, solid, and simple, whereas that of chasmosaurines is greatly elaborated. For example, the nasal septum of chasmosaurines is thickened into a stout narial strut along its caudal margin. Further rostrally, the septum is indented by a fossa, which is variably perforated by an interseptal foramen in most taxa (e.g., Anchiceratops, Triceratops). Ventral to this perforation of the nasal septum, more derived chasmosaurines have a variably sized diverticulum that opens into the premaxillary body. Chasmosaurines also have a triangular process that projects into the external naris from the base of the narial strut (Forster 1996a); in some taxa (e.g., Triceratops) this triangular process is invaginated by a fossa on its lateral surface. These elaborate premaxillary fossae, foramina, and processes characteristic of chasmosaurines are directly linked with an intrapremaxillary cavity, and all of these features may be of pneumatic origin, derived from a paranasal air sac (Sampson and Witmer 1999). Centrosaurines lack pneumatic premaxillae, but possess other specializations of this element, including a small process formed by the nasal and premaxilla that projects forward from the caudal border of the external naris. The thickened oral margin of the premaxilla is flat in chasmosaurines to meet a horizontal cutting edge of the predentary, whereas it is angled in centrosaurines to overlap a laterally beveled predentary cutting surface. Ventrally, medial flanges of the premaxillae meet the premaxillary processes of the maxillae to form a short hard palate.

The maxilla forms at least half the height of the face. A prominent longitudinal ridge on the dorsal maxilla marks its restricted contact with the jugal. In ceratopsids, the dentigerous portion of the maxilla continues caudally some distance medial to the jugal. The greatly reduced antorbital fenestra is situated in a cleft on the dorsal maxilla between its jugal and lacrimal processes. There is much individual variability in the prominence of this feature and it is barely detectable in some individuals.

The small, quadrilateral lacrimal forms the rostral margin of the orbit between the jugal ventrally and the prefrontal dorsally. The lacrimal is small in ceratopsids, forming only a small portion of the orbit margin. Unlike in most dinosaurs, this element is not pierced by a lacrimal foramen. The lacrimal roofs the antorbital fenestra rostrally and contacts the nasal rostrodorsally. Early fusion of the lacrimal frequently obscures its borders with adjacent elements.

The nasal is a major element of the face in ceratopsids, bearing a small to prominent bony horn-core in most taxa. The horn-core was presumably covered in life with a horny, keratinous sheath that would have increased the total length of this structure. The nasal horn-cores of centrosaurines tend to be large (up to 500 mm in length for Styracosaurus), whereas those of chasmosaurines are uniformly small. The horn-core is formed by fusion of the paired nasals, which co-ossify from the tip downward, as indicated by a number of juveniles (Gilmore 1917; Sampson et al. 1997). Centrosaurine nasal horn-cores are always centered over the rear of the external nares. In some centrosaurines (Centrosaurus, Styracosaurus), the unmodified nasal horn-cores are often tall and straight with well-defined and sometimes constricted bases. In contrast, Einiosaurus is characterized by a large nasal horn-core that is hooked strongly forward in some individuals. In other centrosaurine taxa (Achelousaurus, Pachyrhinosaurus) the nasal horn-cores were apparently modified during ontogeny to develop gnarled, pachyostotic bosses in adults (Sternberg 1950; Langston 1967, 1975; Sampson 1995). Among chasmosaurines, the nasal horn-core is centered at the rear of the external narial margin in some taxa (e.g., Chasmosaurus), but shifts forward to a position over the premaxillary septum in more derived chasmosaurines (e.g., Torosaurus, Triceratops). Although the horn-core of chasmosaurines is also formed primarily from outgrowths of the nasals, a separate center of ossification augmenting the rostral side of the nasal horn-core, an “epinasal ossification,” has been postulated. This accessory element was first described by Hatcher et al. (1907), disputed by Sternberg (1949), then reiterated by Ostrom and Wellnhofer (1986), Lehman (1990), and Forster (1996a). Epinasal ossifications have thus far been observed in some Chasmosaurus and Triceratops, but not in any other chasmosaurine. This situation may be due to the rarity of juvenile chasmosaurines.

Bones of the postnasal midline series and of the dorsal orbital series are highly modified in ceratopsids. The relevant sutures were subject to early fusion during growth, and few skulls exhibit them clearly. Two salient changes involve the prefrontal and supraorbital (= palpebral of the authors). In some centrosaurines (Styracosaurus and Centrosaurus), medial expansion of the prefrontals results in midline contact of these elements, with consequent separation of the nasals from the frontals (Forster 1990b). Other centrosaurines, as well as chasmosaurines, reflect the primitive state for this character, retaining a broad nasal-frontal contact. A supraorbital is rarely discernible on the skulls of mature ceratopsids, but subadult skulls and isolated material show it to be a blocky element that fused with the prefrontal via a broad, rugose contact, thereby excluding the latter from the orbital rim (Sampson 1993). The supraorbital makes a rostroventral contribution to the orbital horn-core in at least centrosaurines, and likely in all ceratopsids.

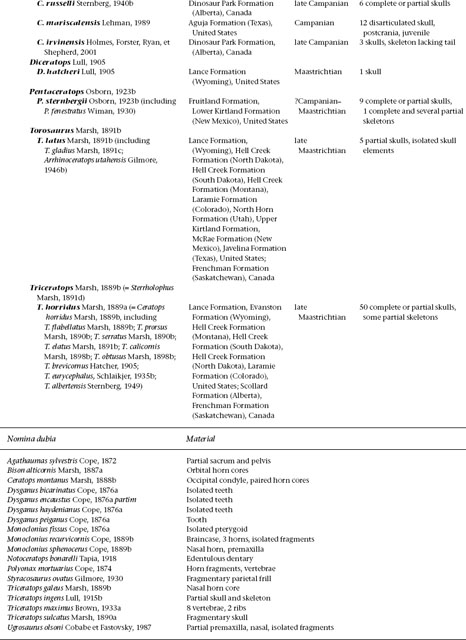

FIGURE 23.1. Skulls of Centrosaurinae: A, Avaceratops lammersi; B, Centrosaurus apertus; C, D, Styracosaurus albertensis, C, lateral view, D, dorsal view; E, Einiosaurus procurvicornis; F, Achelosaurus horneri; G, Pachyrhinosaurus canadensis. Scale = 20 cm. (A from Penkalski and Dodson 1999; B-D after Lull 1933; E, F after Sampson 1995.)

The postorbital is a major bone of the dorsal orbit and cheek. The supraorbital horn-cores are outgrowths of this bone, as indicated by ontogenetic series (Sampson et al. 1997). The suggestion that the supraorbital horn-cores are derived from separate centers of ossification that fuse to the postorbital (Huene 1911; Lambe 1913) has not been substantiated. Adults of certain centrosaurine taxa (Styracosaurus, Pachyrhinosaurus, Einiosaurus) show irregular depressions above the orbits rather than well-formed supraorbital horns. Dodson and Currie (1990) suggested these may represent the loss of a separate center of ossification. More recently it has been suggested that these pits result from the resorption of part or all of the supraorbital horn-cores (Sampson et al. 1997). Particularly convincing in this regard are numerous individuals spanning an array of resorption stages, from small terminal pits on horn-cores to elaborate excavations replacing the horn-core altogether. The orbital horn-cores of centrosaurines are usually less than 150 mm in height, and two taxa (Achelousaurus and Pachyrhinosaurus) had their supraorbital horn-cores ontogenetically replaced with gnarled, pachyostotic bosses. Supraorbital horn-cores of large chasmosaurines may approach 1 m in length and have massive, hollow bases. Most Chasmosaurus belli and C. russelli also have short, centrosaurine-like supraorbital horns and occasionally exhibit pitting and resorption. In Chasmosaurus irvinensis horn-cores are absent, replaced by pitted excavations, as in some centrosaurines.

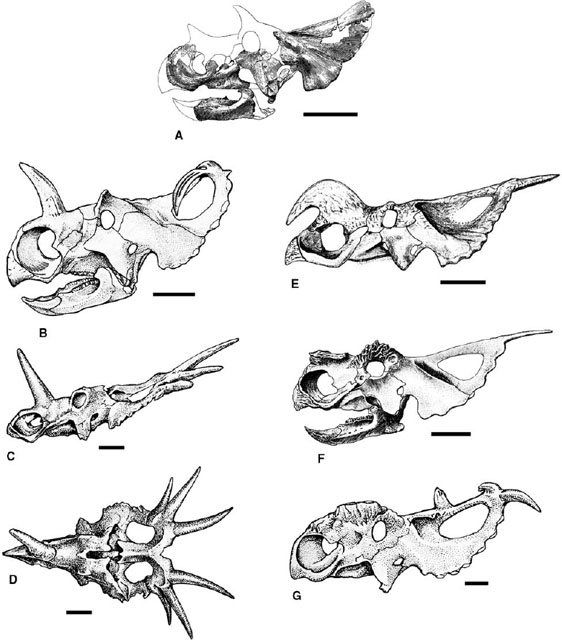

FIGURE 23.2. Skulls of Chasmosaurinae: A, Anchiceratops ornatus (lateral and dorsal views); B, Chasmosaurus belli (lateral and dorsal views); C, Chasmosaurus belli; D, Chasmosaurus russelli; E, Arrhinoceratops brachyops; F, Torosaurus latus; G, Triceratops horridus; H, Triceratops horridus; I, Pentaceratops sternbergii. Scale = 20 cm. (A-C, E-G, I after Lull 1933; D after Godfrey and Holmes 1995.)

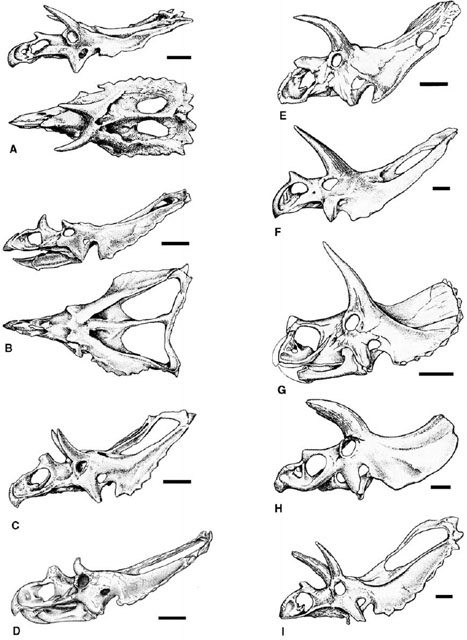

FIGURE 23.3. Skull of Triceratops horridus: A, lateral view; B, occipital view; C, dorsal view; D, palatal view. Scale = 20 cm (A, B, C), scale = 10 cm (D). (After Hatcher et al. 1907.)

The enlarged jugal has the form of an inverted triangle, the base of which forms the ventral rim of the orbit. The jugal is expanded ventrally into an elongate flange, extending almost to the distal end of the quadrate and overlapping the caudal process of the maxilla. The distal tip of the jugal flange is thickened and accentuated by an epidermal ossification, the epijugal. Among ceratopsids, epijugals are more pronounced in chasmosaurines. The epijugal of Arrhinoceratops brachyops (Parks 1925) and Pentaceratops sternbergii (Osborn 1923b) forms a pronounced, laterally projecting jugal “horn,” in which the thickness exceeds the width of the ventral end of the quadrate. Epijugals are not prominent in other chasmosaurines (e.g., Chasmosaurus, Triceratops), although they are distinct ossifications. The caudomedial surface of the ventral tip of the jugal shows a rugose surface where it overlaps the quadratojugal. In some ceratopsids (e.g., Triceratops), the epijugal may also articulate with the quadratojugal. A broad jugal-squamosal contact above the infratemporal fenestra characterizes ceratopsids. In centrosaurines and some species of the chasmosaurine Chasmosaurus (C. belli, C. russelli), the jugal develops a caudal flange that contacts the squamosal below the infratemporal fenestra.

Ceratopsids exhibit considerable reorganization of the cheek region. The ventral end of the quadrate is rotated forward, the infratemporal fenestra is pushed ventrally below the level of the orbit and reduced in size, and the jugal, quadratojugal, and quadrate are telescoped so as to lie side by side rather than in series front to back (Forster 1990b; Dodson 1993). The quadratojugal is thus reduced to a spacer element interposed between the jugal flange and the quadrate. The quadrate is short in ceratopsids and is covered in lateral view by the squamosal, quadratojugal, and jugal. The ventral end of the quadrate is robust and transversely expanded, but the dorsal end is extremely thin. The quadrate does not have a “head” in ceratopsids, but rather its entire proximolateral margin fits inside a long slot on the ventral surface of the squamosal. This arrangement precluded any streptostyly (Weishampel 1984a). A distinct shallow fossa for the pterygoid on the pterygoid ramus of the quadrate is characteristic of ceratopsids. The quadratojugal is thick caudoventrally and thins dorsally, wrapping around to the caudal surface of the midquadrate shaft. Although the quadratojugal is largely obscured in lateral view by the jugal, its degree of exposure adjacent to the infratemporal opening is variable both individually and taxonomically.

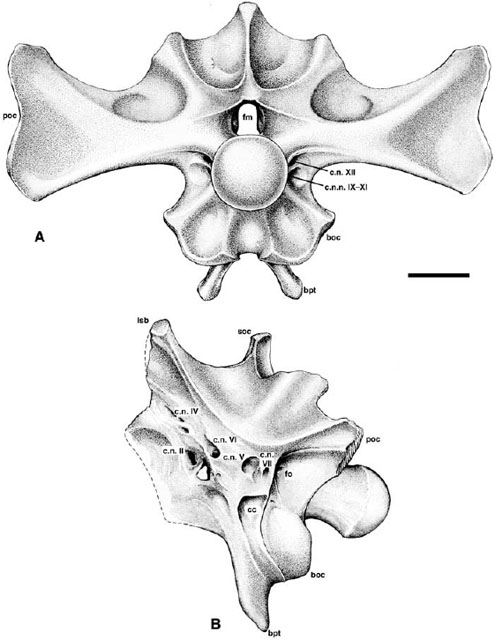

FIGURE 23.4. Braincase of Centrosaurus apertus: A, occipital view; B, left lateral view. Scale = 5 cm.

In ceratopsids, the fused frontals are restricted in extent and excluded from the orbit. The frontals also do not contribute to the supratemporal fenestra, which is composed of the postorbital, the squamosal, and the parietal. Although this area of the skull is firmly coossified in adult ceratopsids, these relationships are evident in juvenile centrosaurines. A feature unique to Ceratopsidae is the supracranial cavity, a system of smooth-walled, bony spaces dorsal to the braincase that opens onto the dorsum of the skull via an aperture variously referred to as the frontal fontanelle (Sternberg 1927a) or postfrontal fontanelle (Gilmore 1919b). The supracranial cavity is absent or nascent in juveniles (Gilmore 1917) and highly variable among adults of various ceratopsid taxa. It is shallow, narrow, and simple in some adult centrosaurines (e.g., Centrosaurus) and chasmosaurines (e.g., Chasmosaurus), whereas adults of other taxa possess more elaborate, extensive cavities divided into complex series of chambers by bony septa. Among certain taxa exhibiting the latter condition (e.g., Triceratops, Pachyrhinosaurus), the supracranial cavity extends laterally and dorsally to invade and hollow the base of the supraorbital ornamentation (horn-core or boss) (Forster 1990b). Minimally, however, the supracranial cavity system includes the frontals, the postorbitals, the parietals, and the supraoccipital.

The dorsal opening of the supracranial cavity, the frontal fontanelle, is formed by the frontals rostrally and laterally and the parietal caudally. Caudal expansion of the frontal eliminates the postorbital from the dorsal midline, as well as from the border of the frontal fontanelle (Forster 1990b; Sampson 1995). The size and shape of the fontanelle vary greatly among ceratopsids, being rostrocaudally elongate and narrow in centrosaurines and ranging from keyhole-shaped (Chasmosaurus, Pentaceratops) to oval or round (e.g., Anchiceratops, Triceratops) in chasmosaurines. Remarkably, a number of skulls representing both Centrosaurinae and Chasmosaurinae indicate that an additional opening pierced the floor of the supracranial cavity, forming a direct bony communication with the endocranial cavity (Gilmore 1917, 1919a; Lehman 1989; Forster 1990b; Sampson 1995; Sampson et al. 1997). This feature may be variable among ceratopsids, or even among individuals of the same taxon. For example, this opening is found in some Triceratops, but closed over by a thin layer of bone in others (Sternberg 1927a; Lull 1933; Forster 1996a). This latter opening, referred to as the frontoparietal foramen, was thought to house a photosensitive organ homologous with the pineal eye (Gilmore 1919a; Lehman, 1989), but this relationship is unlikely (Sampson et al. 1997). To date, the function of this aperture remains unknown.

In addition to their various horn morphologies, ceratopsids are easily recognized by the presence of an enlarged, elaborate, caudally projecting bony frill. Determination of the bony composition of this frill, particularly the median element, was problematic (Hay 1909; Huene 1911; Brown 1914c; Gilmore 1919b), at least until the discovery and description of the basal ceratopsian Protoceratops andrewsi (Granger and Gregory 1923; Gregory and Mook 1925). It then became clear (Sternberg 1927a; Brown and Schlaikjer 1940a) that the median portion is composed of fused parietals, as was asserted by Marsh (1891a) and Hatcher et al. (1907), while the paired squamosals formed the lateral (Chasmosaurinae) or rostrolateral (Centrosaurinae) portions. Among ceratopsids the large parietosquamosal frill varies from 60% to slightly over 100% of the basal skull length. Despite the apparent enormity of this structure, it is no larger relative to the basal skull length than the frill of Protoceratops (65%-70%). In general, the frill is short in centrosaurines and the chasmosaurine Triceratops, but more elongate in other chasmosaurines such as Anchiceratops, Torosaurus, and Pentaceratops. Bilateral fenestrae are found in the parietals of nearly all taxa; these openings are hypertrophied in species of Chasmosaurus and Pentaceratops, greatly reduced in Diceratops, and secondarily closed in Triceratops.

The ceratopsid squamosal is a flattened, complex element that contacts the jugal, quadratojugal, and postorbital rostromedially; the parietal medially and caudally; and the quadrate and paroccipital process rostroventrally. In centrosaurines, the squamosal is significantly shorter than the parietal, and the length of the postquadrate portion of the squamosal exceeds that of the rostral prequadrate portion by as much as three to two (Avaceratops is an exception). In chasmosaurines, the squamosal is enormous, equaling the parietal in length. In the small Chasmosaurus belli, the squamosal is often less than 1 m in length, whereas in one Torosaurus latus (Colbert and Bump 1947), the squamosal measures 1.43 m. In chasmosaurines, the postquadrate portion may exceed the rostral portion by four to one. The ceratopsid squamosal is constricted opposite the quadrate articulation to form a jugal notch. On the medial surface of the squamosal, the attachment of the exoccipital is marked by a prominent ridge, rostral to which is the long slotlike cotylus for the quadrate. In chasmosaurines, squamosal fenestrae, usually unilateral, are a common intraspecific variant in all genera except Triceratops. Although it has been suggested that these fenestrae are injury related (Lull 1933; Molnar 1977), their consistent position on the squamosal and their smooth, even margins argue against this interpretation. In all ceratopsids, the infratemporal fenestra is reduced in size and restricted to a position below the orbit by the dorsoventral expansion of the proximal squamosal. The squamosal shares a broad contact with the jugal, excluding the postorbital from the infratemporal fenestra.

In ceratopsids, the hypertrophied parietals fused at an early ontogenetic stage—even juveniles show no indication of a mid-line suture (Dodson and Currie 1988). The coalesced parietals are generally thickest sagittally and along the external borders. The thinnest areas occur lateral to the midline, regardless of whether or not parietal fenestrae are present. The shape of the caudal external border of the parietal varies from slightly convex (e.g., Triceratops) to deeply embayed (e.g., Pentaceratops, Chasmosaurus mariscalensis). The fused parietals form the caudal margin of the frontal fontanelle, in addition to the caudodorsal portion of the supracranial cavity, as described above. However, in contrast to other dinosaurs (and vertebrates generally), they apparently do not participate in the braincase.

The outer, peripheral margin of both the squamosal and parietal bears a number of regular undulations, which are capped by dermal ossifications known as epoccipitals. Although there has been considerable debate as to whether or not certain taxa lack these accessory ossifications, ontogenetic data suggest that most (and likely all) ceratopsids possessed these features (Sampson et al. 1997). Much of this confusion is due to the fact that epoccipitals often become firmly fused to the frill margin in adults, obscuring any evidence of separate ossification. Epoccipitals vary greatly in shape among ceratopsids, being broad based and triangular in chasmosaurines and more elliptical with constricted bases among centrosaurines. In some chasmosaurines, the parietal epoccipitals are unmodified and directed caudally. However, parietal epoccipitals in other chasmosaurines (e.g., Chasmosaurus, Pentaceratops) and virtually all centrosaurines are modified into a species-specific array of hornlike processes that may be straight or curved, with a variety of orientations. In Pachyrhinosaurus sp., the median parietal bar is also ornamented with several irregular hornlike processes (Tanke 1988; Dodson and Currie 1990; Dodson 1996). In adult centrosaurines, the laterally placed squamosal and parietal processes, with their attached epoccipitals, are imbricate, exhibiting a sine-wavelike morphology in which the rostral border of each process is depressed relative to the caudal border (Sampson et al. 1997). Largely due to the presence of these remarkably varied ornamentations, the parietal is the single most diagnostic element of the ceratopsid skull.

The vaulted secondary palate of ceratopsids has received little attention (Hatcher et al. 1907; Lull 1933; Brown and Schlaikjer 1940a; Sternberg 1940b). The paired choanae are long and large because of the restriction of the palatines caudally. The palatine foramen is lost, and the ectopterygoids are limited in size and eliminated from exposure on the ventral palate by contact between the maxilla and the palatine. The vomer is a straight median bar running between the pterygoids caudally and the palatal processes of the maxillae rostrally. The vomer is rarely observed in ceratopsids, but has been reported in Triceratops (Hatcher et al. 1907), Chasmosaurus belli (Lull 1933), and Achelousaurus horneri (Sampson 1993). In at least the first two taxa, the vomer is oriented horizontally. A caudal transverse wing of the palatine achieves a vertical orientation to contact the lacrimal, prefrontal, and jugal medially in the vicinity of the antorbital foramen. Expansion of the palatine is accompanied by restriction of the ectopterygoid to a small, flattened bone on the dorsum of the caudal process of the maxilla. Contact of the ectopterygoid with the palatine has been lost in ceratopsids. The pterygoid is a complex bone that retains its primitive role as a link between the quadrate and palate, with a brace on the braincase.

In the occipital region, the supraoccipital is excluded from the foramen magnum by a broad contact between the exoccipitals. Distinct vertical elliptical depressions mark the muscular attachments, likely of M. rectus capitis, on the supraoccipital and exoccipital just off the median sagittal plane. A pair of strong rostrodorsal processes of the supraoccipital supports the parietals at their junction with the frontals. The occiput is broad, and the long, deep paroccipital processes extend laterally to brace against the inside of the squamosal. These processes support the dorsal end of the quadrate, as well as the massive frill. Lateral to the supraoccipital, the entire dorsal margin of the parocciptal processes is in contact with the parietal. Two large foramina exit the braincase behind the paroccipital processes, just ventrolateral to the foramen magnum, and transmit c.nn. X, XI, and XII (Forster 1996a). In ceratopsids, the dorsal margin of the paroccipital processes may show prominent depressions, indicating the attachment of M. longissimus capitis, which continue onto the ventral parietal. The exoccipitals form at least two-thirds of the occipital condyle. In large ceratopsids, the occipital condyle is huge, measuring 96 mm in diameter in Pachyrhinosaurus canadensis (Langston 1975) and up to 106 mm in Triceratops horridus (Hatcher et al. 1907). The opisthotic, prootic, and laterosphenoid are firmly fused in ceratopsid braincases, but the position of foramina suggests they likely retain the usual vertebrate arrangement. The orbitosphenoid is apparently ossified although it is rarely seen as separate from the laterosphenoid, owing to early fusion of these elements. It is unknown whether a presphenoid is present. The basisphenoid is indistinguishable from the parasphenoid. The rostral process of the parasphenoid contacts the vomer. The basipterygoid processes are shorter and more vertical in ceratopsids than in more basal ceratopsians.

The long dentary has straight parallel dorsal and ventral borders and a pronounced erect coronoid process. The coronoid process is offset strongly from the ramus and its apex is expanded rostrally into a pointed process. The medial surface of the dentary bears a series of foramina that pierce the bone along the base of each vertical tooth family. A short diastema occurs along the oral margin between the predentary and the first alveolus. A moderate ridge running the length of the dentary on its lateral surface is confluent with the rostral edge of the coronoid process. The tooth row is strongly inset and passes medial to the coronoid process. The dentary is thickest at the base of the coronoid process, where it surrounds the mandibular fossa, which is covered ventromedially by an extensive splenial that meets the articular. In large ceratopsids such as Triceratops and Pentaceratops, the articular is of remarkable breadth, corresponding to the breadth of the quadrate condyle. The surangular contribution to the coronoid process is reduced in ceratopsids, forming only a narrow strip along the caudal coronoid margin. The angular is reduced as well and exposed only on the lateral aspect.

The teeth bear a strong median ridge on their ornamented side (buccal in maxillary teeth, lingual in dentary teeth) and lack the secondary ridges seen in more primitive neoceratopsians. The crown is set at a high angle to the root. The occlusal surface is oriented nearly vertically and is continuous across all the teeth in the battery (Ostrom 1966). The dental battery of ceratopsids consists of three to five teeth in each vertical tooth family, with adjacent tooth crowns tightly packed against one another. The roots of the teeth are split and arranged labially and lingually so that the crown of the tooth below it nestles tightly within the fork of the previous tooth. This interlocking arrangement imparted great stability and ensured a continual replacement of teeth without gaps. Vascular labile bone, similar in structure and function to mammalian cementum, further stabilized each tooth in its alveolus. Lehman (1989) reports an ontogenetic increase from 20 to 28 tooth positions for Chasmosaurus mariscalensis, but ontogenetic data on tooth number are unknown for other ceratopsids. The total number of tooth positions roughly follows absolute skull size, ranging from 28 to 31 in Centrosaurus and from 36 to 40 in Triceratops.

Hyoid bones have been described for Centrosaurus apertus (Parks 1921) and Triceratops horridus (Lull 1933). In C. apertus they take the form of simple slender rods; in T. horridus the rodlike ceratohyals are curved. Sclerotic rings are rarely preserved in ceratopsids. A partial ring in “Monoclonius nasicornis” (= C. apertus, Sampson et al. 1997) preserves only five plates (Brown 1917), each plate overlapping approximately half of the next. The surface of each plate is finely rugose and the margins are irregular.

Postcranial Skeleton

AXIAL SKELETON

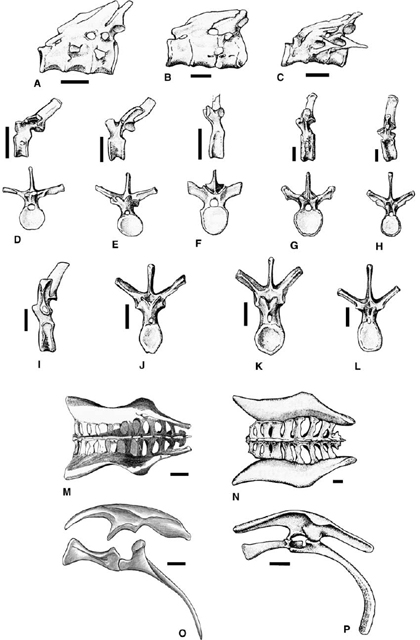

Although there are many fine ceratopsid skulls, postcranial remains are less common in collections, and few have complete vertebral columns (figs. 23.5). Indeed, “Monoclonius nasicornis” (Brown 1917) and Anchiceratops ornatus may be the only ceratopsids in which the complete vertebral column is known. The ceratopsid vertebral formula usually consists of 10 cervicals, 12 dorsals, and 10 sacrals. Complete caudal counts, where known, range from 38 to 50.

Complete coalescence of the centra and neural arches of the first cervicals to form a syncervical (Ostrom and Wellnhofer 1986) or cervical bar (Langston 1975) characterizes all ceratopsids. It has been controversial whether the syncervical incorporates the first three (Brown 1917) or the first four (Hatcher et al. 1907) cervicals; Romer (1956) accepted three or four cervicals. The consensus for many years favored the interpretation of three cervicals (e.g., Parks 1921; Lull 1933; Brown and Schlaikjer 1940a; Sternberg 1951; Langston 1975; Sereno 1986). In the neoceratopsian Leptoceratops gracilis, the atlas is small and bears no neural spine; the first three cervicals co-ossify only when large size is achieved (Sternberg 1951). Ostrom and Wellnhofer (1986) suggest the unlikelihood that the atlas had a separate neural arch in Triceratops. Acceptance of this view implies that the atlas has been severely reduced in most neoceratopsians and that the small cranial element represents a vestigial atlas. However, the complete ring formed by the atlas in Triceratops (Hatcher et al. 1907) may argue for the presence of a fused atlantal centrum and neural arches. The ceratopsid syncervical thus incorporates a fused atlas-axis complex as well as cervicals 3 and 4. This view is accepted herein and vertebral counts are correspondingly adjusted.

Cervicals 5-10 in ceratopsids are short and broad. The neural spines are uniform in height in Triceratops (Hatcher et al. 1907; Ostrom and Wellnhofer 1986), whereas in other ceratopsids the spines form a graded series increasing in height caudally. The cervical neural spines are low in long-frilled Chasmosaurus belli (Sternberg 1927b) and Pentaceratops sternbergii (Wiman 1930), and comparatively high in Anchiceratops ornatus (Lull 1933). Adventitious fusion of cervicals 5 and 6 is reported in Styracosaurus albertensis (Brown and Schlaikjer 1937) and of cervicals 6 and 7 in Centrosaurus apertus (Lull 1933). Cervical 10 is the last presacral vertebra with the capitular facet on the centrum (Brown 1917). Double-headed ribs are borne on all centra beginning with cervical 3. The tuberculum is prominent, and the shaft is short and straight. Elongation of the ribs usually begins with the sixth except for Triceratops, in which the eighth rib is short as well (Ostrom and Wellnhofer 1986). The first long rib articulates with cervical 9 (considered dorsal 1 by Hatcher et al. 1907).

FIGURE 23.5. Axial skeleton and pelvis of ceratopsids: A–C, syncervical vertebrae (left lateral view), A, Styracosaurus albertensis, B, Pachyrhinosaurus canadensis, C, Triceratops horridus; D, cranial dorsal vertebra of Centrosaurus apertus (left lateral and cranial views); E, mid-dorsal vertebra of Centrosaurus apertus (left lateral and cranial views); F, dorsal vertebra of Chasmosaurus canadensis (left lateral and cranial views); G, cranial dorsal vertebra of Triceratops horridus (left lateral and cranial views); H, caudal dorsal vertebra of Triceratops horridus (left lateral and cranial views); I, dorsal vertebra of Centrosaurus apertus (left lateral view); J-L, dorsal vertebra (cranial view), J, Styracosaurus albertensis, K, Pachyrhinosaurus canadensis, L, Triceratops horridus; M, N, sacrum and ilia (dorsal view), M, Centrosaurus apertus (= “Monoclonius flexus”), N, Triceratops horridus; O, P, pelvis (left lateral view), O, Centrosaurus flexus, P, Chasmosaurus mariscalensis. Scale = 10 cm. (A, B, J, K after Langston 1975; C, D, G, H, L, N after Hatcher et al. 1907; E, I, M after Lull 1933; F after Tyson 1977; P after Lehman 1989.)

The usual number of free dorsals in ceratopsians is 12, but up to three additional dorsal centra may be incorporated into the sacrum as sacrodorsals. In ceratopsids, the dorsal centra are axially short and the neural arches are high. Mid-dorsal centra are significantly narrower than midcervical centra, a feature that is more striking in chasmosaurines than in centrosaurines. Faces of the dorsal centra are either round or pear-shaped. The neural canal decreases in diameter caudally along the dorsal series. Transverse processes are strongly elevated by dorsal 3 but decrease in prominence in the caudal half of the series, the region in which the zygapophyses increase in prominence. Neural spines are robust and generally show little variation in height, although there is more variation in Chasmosaurus belli (Sternberg 1927b) and Pentaceratops sternbergii (Wiman 1930) than in others. The tallest dorsal spine varies in position from dorsal 5 to 7 (C. belli, P. sternbergii, Sternberg 1927b; Wiman 1930), to dorsal 7 to 8 (Centrosaurus apertus, Brown 1917; Lull 1933). Bundles of ossified epaxial tendons have been noted in the cranial dorsal region of Styracosaurus albertensis (Brown and Schlaikjer 1937), the mid-dorsal region of Triceratops horridus (Hatcher et al. 1907), and the dorsal and sacral regions of “M. nasicornis” (Brown 1917). In T. horridus tendons lie parallel at the summits of the arches. In “M. nasicornis,” Brown described a “mass” of tendons, lacking any regular order, possibly due to poor preservation of their original positions. It is reasonable to assume that all ceratopsids had ossified epaxial tendons. Dorsal ribs are figured by Gilmore (1917) and Ostrom and Wellnhofer (1986), and are described by Brown (1917). The second to sixth dorsal ribs are subequal in length, after which there is a variable shortening caudally. The twelfth rib may be weak. The cranial dorsal ribs are comparatively straight with a prominent tuberculum widely separated from the capitulum. In the mid-dorsal region, the ribs are more curved and the tuberculum less prominent. Caudally, the tuberculum is weak and closer to the rib head.

The sacrum of ceratopsids consists of ten variably ankylosed centra (11 in Pentaceratops sternbergii, Wiman 1930), including three sacrodorsals, four sacrals with both transverse processes and sacral ribs, and three sacrocaudals. The degree of fusion among sacral vertebrae has a strong ontogenetic basis. In the juvenile centrosaurine “Brachyceratops montanensis” (USNM 7951; Gilmore 1917), there is no fusion, but eight centra are in sutural contact. A heavy, ventral acetabular bar, formed by the fusion of distally expanded sacral ribs, runs half the length of the sacrum. Sacral ribs are robust and abut the ilium; expanded distal ends may fuse (in Triceratops horridus, cranial four and caudal two; Hatcher et al. 1907). In Triceratops and Pentaceratops sternbergii, the seventh and eighth transverse processes are the longest, and the following ones are shorter, thus imparting an “oval” shape to the sacrum in dorsal view. However, in Centrosaurus apertus (Lull 1933), the oval shape is scarcely discernible. The neural arches are low and broad and fused to a variable degree. In Pentaceratops all spines are distinct; in Triceratops spines 2 to 5 are fused; and in Styracosaurus albertensis (Brown 1917), spines 2 to 7 are fused. Sacral centra are wide and low, and the sacrum is arched dorsally, with the result that the base of the tail is directed downward. The ventral surface of the sacrum is strongly excavated in chasmosaurines and less strongly so in centrosaurines (Lehman 1990). In the juvenile centrosaurine Brachyceratops montanensis, the first sacral is the broadest, while in Centrosaurus apertus, sacrals I-III are wide, sacrals IV-VII are narrow, and the remaining sacrals broaden again.

Complete caudal series are rarely found. The number of caudals in Styracosaurus albertensis is 46 (Brown 1917), and in Anchiceratops ornatus 38 or 39 (Lull 1933). In Pentaceratops sternbergii, 28 caudals are preserved (Wiman 1930), and the last is so small that it is unlikely there were more than about five others. The caudals are simple, the size of all components decreasing steadily toward the end of the tail. Transverse processes terminate halfway down the tail (caudal 19 in Pentaceratops fenestratus, caudal 23 in Styracosaurus albertensis, caudal 25 in Brachyceratops montanensis). Chevrons are about as long as their corresponding neural spines but incline backward more strongly; they terminate about five segments from the end of the tail.

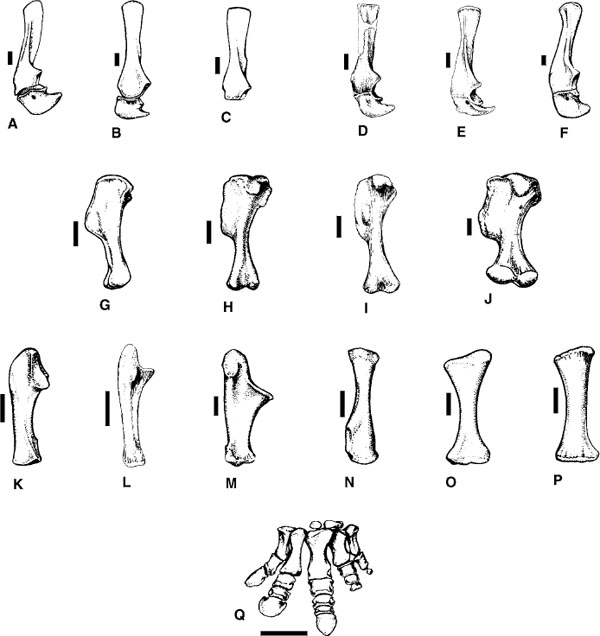

APPENDICULAR SKELETON

Long bones of large ceratopsid genera (e.g., Triceratops, Torosaurus, Hatcher et al. 1907; Johnson and Ostrom 1995) show hypertrophied ends with rugose textures, otherwise seen in sauropods, which are indicative of thick terminal cartilage pads. Medium-sized ceratopsids (e.g., Centrosaurus, Chasmosaurus) have more modestly expanded ends with smooth textures. A scapular spine is prominent in ceratopsids, usually crossing from the caudal supraglenoid ridge distally to the craniodorsal blade (fig. 23.6). The large coracoid has a long caudal process that effectively limited the range of humeral extension. In adults the coracoid fuses to the scapula, which forms two-thirds of the glenoid fossa, with the coracoid forming one-third. Ossified clavicles have never been reported in ceratopsids. Paired, flat, bean-shaped sternal plates are closely appressed and may have supported cartilaginous sternal ribs.

There is always a strong disparity in the relative lengths of the forelimbs and hindlimbs, the former being only about 70% the length of the latter. The head of the humerus is hemispheric and eccentric, extending onto the proximocaudal surface of humerus. In ceratopsids the prominent deltopectoral crest extends distally half or more the length of the humerus. Ceratopsids have a pronounced olecranon process on the ulna, longer in chasmosaurines than in centrosaurines (Adams 1988). The humerus exceeds the radius in length. Four small, flat carpals are ossified in ceratopsids. The manus is always smaller than the pes and is comparatively short and broad. The metacarpals do not tightly interlock with one another, and were apparently arranged to form a strong arch when viewed proximally. The phalangeal formula of the manus is 2-3-4-3-1 or 2. The unguals on the first three digits are small, dorsoventrally compressed, and blunt and irregular distally. Digits IV and V terminate in small, irregular nubbins of bone.

In ceratopsids, the ilium is long and low, straight in forms such as Triceratops (Hatcher et al. 1907), but showing marked deflection of the cranial preacetabular process in others such as Chasmosaurus (Lehman 1989). The entire dorsal margin is everted into a horizontal shelflike structure. A large supracetabular process (“antitrochanter”) lies caudal to the ischial peduncle. The prepubic process is pronounced, extending as far cranially as the tip of the ilium and flaring distally. The pubic shaft is extremely short, barely reaching beyond the acetabulum. The ischium is robust and decurved. This curve is extremely developed in chasmosaurines (Lehman 1990). The femur (fig. 23.7) is always longer than the tibia, even among juveniles (e.g., Brachyceratops montanensis, Gilmore 1917; Avaceratops lammersi, Dodson 1986). The greater and cranial trochanters are fused on the proximal femur and the fourth trochanter is reduced to a low prominence approximately halfway down the femur. The distal femoral condyles are nearly equal in size; however, the lateral condyle extends more distally than the medial one (Lehman 1982). From this, it may be inferred that the action of the femur was not in the vertical plane. Calcanea are flattened and may be fused to the lateral aspect of the astragalus. Two distal tarsals are usually found, although three are reported in Chasmosaurus belli (Lull 1933) and Brachyceratops montanensis (Gilmore 1917). The foot is short and robust. There are four functional metatarsals (I-IV) and frequently a small splint representing metatarsal V. The phalangeal formula in all neoceratopsians is 2-3-4-5-0. Unguals are blunt and rounded with irregular margins.

FIGURE 23.6. Forelimb skeleton of ceratopsids: A, B, left scapulocoracoid of Centrosaurus apertus (lateral view); C, left scapula of Styracosaurus albertensis (lateral view); D-F, left scapulocoracoid (lateral view), D, Chasmosaurus mariscalensis (lateral view; after Lehman 1989), E, Pentaceratops sp., F, Triceratops horridus; G-J, left humerus (caudal view), G, H, Centrosaurus apertus, I, Chasmosaurus mariscalensis, J, Triceratops horridus; K-M, left ulna (medial view), K, Centrosaurus apertus, L, Chasmosaurus mariscalensis, M, Triceratops horridus; N-P, left radius (cranial view), N, Centrosaurus apertus, O, Chasmosaurus belli, P, Triceratops horridus; Q, left manus of Centrosaurus apertus (dorsal view). Scale = 10 cm. (A, G, K, N, Q after Lull 1933; B, H after Parks 192; C after Langston 1975; D, I, L after Lehman 1989; E after Lehman, 1993; F, J, M, P, after Hatcher et al. 1907.)

Integument

Impressions of patches of skin have been described for several ceratopsids (Chasmosaurus belli, Lambe 1914b; “Monoclonius nasicornis,” and “M. cutleri,” Brown 1917; C. belli, Sternberg 1925; “M. cutleri,” Lull 1933). A large impression from the right pelvic area of C. belli (Sternberg 1925) shows a texture of large circular plates up to 55 mm in diameter set in irregular rows and decreasing in size ventrally. The spacing between plates varies from 50 to 100 mm. Between the circular plates are fields of smaller, polygonal, nonimbricating scales. In “M. cutleri” (Brown 1917; Lull 1933:pl. III), skin over the distal femur has the same general pattern as described for Chasmosaurus belli, except that the rounded plates are more widely separated.

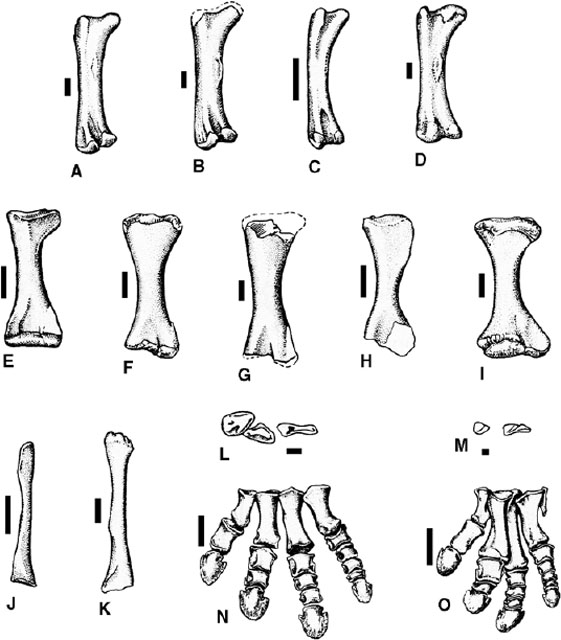

FIGURE 23.7. Hindlimb elements of ceratopsids: A-D, left femur (caudal view), A, Styracosaurus albertensis; B, Pachyrhinosaurus canadensis, C, Chasmosaurus belli, D, Triceratops horridus; E, left tibia, astragalus, and calcaneum Centrosaurus apertus (cranial view) ; F-H, left tibia (cranial view), F, Styracosaurus albertensis, G, Pachyrhinosaurus canadensis, H, Chasmosaurus belli; I, left tibia, astragalus, and calcaneum of Triceratops horridus (cranial view); J, K, left fibula (lateral view), J, Centrosaurus apertus, K, Triceratops horridus; L, M, left distal tarsals (proximal view), L, “Brachyceratops montanensis,” M, Centrosaurus apertus; N, O, left pes (dorsal view), N, Centrosaurus sp., O, Centrosaurus apertus. Scale = 10 cm. (A, B, F, G, after Langston 1975; D, I, K after Hatcher et al. 1907; E, J after Lull 1933; L after Gilmore 1917; M after Brown and Schlaikjer 1940a; N, O after Brown 1917.)

Phylogeny and Evolution

An understanding of intraspecific variation, either explicit or implicit, is a prerequisite for phylogenetic analysis—species identified in such research must obviously represent discrete biological units. With such an abundant fossil record, ceratopsids provide a rare opportunity to address the issue of variation directly, and several recent studies have done just that. For example, a century of paleontology in western North America resulted in 16 named species of Triceratops, distinguished from one another on the basis of minor variations in skull morphology. Modern thought has emphasized within-species biological variability as a basis for rationalizing taxonomy. Ostrom and Wellnhofer (1986), arguing largely on the basis of analogy with extant herbivorous taxa, posited that all of this variation could be accommodated within a single species, Triceratops horridus.

Forster (1996b) took a more rigorous approach to the Triceratops problem, conducting a morphometric and cladistic study of skulls in order to address this issue of species resolution. She identified two forms that overlap geographically and stratigraphically—one centered on T. horridus and the other on T. prorsus. While recognizing that sexual dimorphism may be a causal factor, Forster accepted these different forms as valid species based on the congruence of three variable characters within the genus and a separation of the two in morphospace. She also recognized the closely related Diceratops hatcheri, represented by a single skull, as an additional valid taxon. Subsequently, Lehman (1990, 1998) followed Ostrom and Wellnhofer (1986), arguing for a single, morphologically diverse species of Triceratops. According to Lehman, the characters distinguishing the two species of Triceratops in Forster's scheme are gradational and consistent with intraspecific variation rather than discrete morphs. Similar disagreements have complicated understanding of the species of Chasmosaurus from Alberta. Godfrey and Holmes (1995) analyzed variability in Chasmosaurus and recognized two morphs, which they interpreted as two species (C. russelli and C. belli). Lehman (1997) later argued that these differences are due to intraspecific variability, and he postulated a single species of Chasmosaurus. Recent efforts to relocate Chasmosaurus in a stratigraphic context suggests that these two forms of Chasmosaurus occur in different levels of the Dinosaur Park Formation, strengthening the view that they represent two distinct species (Holmes et al. 2001; Ryan, pers. comm.). Recently, a third species of Chasmosaurus from Alberta was named, C. irvinensis, which occurred in younger strata than either C. belli or C. russelli (Holmes et al. 2001).

Detailed studies of large, low-diversity bone beds (see below) have also yielded primary insights into ceratopsid variation (Lehman 1989; Rogers 1990; Ryan 1990; Sampson 1995; Sampson et al. 1997; Sampson and Ryan 1997). In particular, these studies have increased our understanding of ceratopsid ontogeny, which has obvious relevance in delimiting taxa for phylogenetic analyses. Sampson et al. (1997) examined large fossil samples from several centrosaurine bone beds and establish three age classes (juvenile, subadult, and adult) on the basis of multiple criteria (e.g., suture closure, absolute size, bone surface texture). They found that most species-specific characters occur on the horns and frills and that these features were expressed fully only after the onset of adult size. As a result of this pattern of retarded growth, which is also common among extant vertebrates, centrosaurine juveniles look similar, and it is difficult to distinguish taxa based solely on juvenile or subadult remains. Moreover, Sampson et al. (1997) argued that certain taxa—namely Brachyceratops montanensis and Monoclonius crassus—should be regarded as nomina dubia since they are based on juveniles and/or subadults that had not expressed adult features at the time of death. In support of the latter notion, large but unadorned, “Monoclonius-like” skull elements were recovered from virtually all of the bone beds, which span millions of years in the Campanian and Maastrichtian.

Tumarkin and Dodson (1998) accepted the age criteria advanced by Sampson et al. (1997) and further developed the concept of heterochrony as an important mechanism enhancing the evolution of ceratopsid diversity. Heterochrony, the change of timing of developmental events in relation to the ancestral condition, is held by Weishampel and Horner (1994) and Long and McNamara (1997) to be a major and hitherto largely unrecognized factor in the morphological evolution of dinosaurs. Tumarkin and Dodson (1998) took issue with the view that Monoclonius crassus should be regarded as an invalid taxon. In their opinion, at least one individual (referred to “Monoclonius lowei”) is too large to be a juvenile of any known Judithian centrosaurine; instead they interpret it as a neotenic form; that is, one that maintains juvenile morphology at large size. By similar reasoning, they believe that Avaceratops may be a progenetic form that matured at a small body size. However, other researchers consider Avaceratops to be simply a juvenile or subadult (e.g., Sampson et al. 1997). These issues are unresolved, but studies are under way to develop modern models for aging techniques such as bone texture development.

If the horns and frills of ceratopsids functioned as sexual signaling devices (see below), one might expect to find a high degree of sexual dimorphism. Dimorphism between the sexes has been postulated for the basal ceratopsian Protoceratops (Kurzanov 1972; Dodson 1976). Dodson (1976), in particular, found the most reliable indicators of sex to be the nasal prominence and the parietosquamosal frill shape in Protoceratops. Sexual dimorphism in horn and frill morphologies has also been posited for several ceratopsids, including both chasmosaurines (Lehman 1989, 1990) and centrosaurines (Dodson 1990c). Sample sizes are invariably small, however, and are further hampered by postmortem distortion (e.g., Forster 1990b). Thus, while two morphs may be identifiable within a given sample, it is often impossible to determine whether this variation relates to sexual differences, phylogenetic separation, or even intraspecific variation. Thus, to date, there is no unequivocal evidence of sexual dimorphism—relating either to body size or ornamentation—in any ceratopsid (Forster 1990b; Sampson et al. 1997; Lehman 1998).

Interestingly, however, among various extant vertebrates, sexual dimorphism tends to be minimal or absent in small-bodied taxa, greatest in middle-size taxa (80-300 kg), and reduced in large-bodied taxa (>300 kg), particularly in gregarious forms inhabiting open environments (Walther 1966; Estes 1974; Geist 1974, 1978; Jarman 1983). Sexual dimorphism in the latter category tends to be concentrated on horns and other “social organs.” Thus, given that there is independent evidence suggesting that ceratopsids may be gregarious and/or lived in open environments (see below), it may be that the observed pattern also characterized ceratopsids. Sampson et al. (1997) expected to find minimal sexual dimorphism in ceratopsids and, where present, dimorphism should be concentrated in the horns and frills.

The investigation of these myriad sources of variation in ceratopsids and their apportionment to individual, ontogenetic, sexually dimorphic, and species-specific variation has provided the basis for much discussion of ceratopsid phylogenetic relationships. Ceratopsidae has always been considered a monophyletic group (e.g., Hatcher et al. 1907), a view supported by numerous recent studies (e.g., Sereno 1984, 1986; Marya ska and Osmólska 1985; Dodson and Currie 1990; Forster 1990b; Sampson 1995). Hatcher et al. (1907) divided Ceratopsidae into two groups: a Monoclonius-Triceratops group (also including Diceratops, “Agathaumus,” and Centrosaurus), and a “Ceratops”—Torosaurus group. Lambe (1915) later divided ceratopsids into three subfamilies: Eoceratopsinae, Centrosaurinae, and Chasmosaurinae. Lull (1933) reverted to the two-group system of Hatcher et al., diagnosing each group largely on the basis of frill length. Lull recognized a “short-crested” lineage (Centrosaurus, Styracosaurus, Triceratops) and a “long-crested” lineage (Chasmosaurus, Anchiceratops, Pentaceratops, Arrhinoceratops, Torosaurus), and this division has persisted in both the scientific and popular literature (e.g., Steel 1969; Thulborn 1971a; Colbert 1981; Norman 1985).

ska and Osmólska 1985; Dodson and Currie 1990; Forster 1990b; Sampson 1995). Hatcher et al. (1907) divided Ceratopsidae into two groups: a Monoclonius-Triceratops group (also including Diceratops, “Agathaumus,” and Centrosaurus), and a “Ceratops”—Torosaurus group. Lambe (1915) later divided ceratopsids into three subfamilies: Eoceratopsinae, Centrosaurinae, and Chasmosaurinae. Lull (1933) reverted to the two-group system of Hatcher et al., diagnosing each group largely on the basis of frill length. Lull recognized a “short-crested” lineage (Centrosaurus, Styracosaurus, Triceratops) and a “long-crested” lineage (Chasmosaurus, Anchiceratops, Pentaceratops, Arrhinoceratops, Torosaurus), and this division has persisted in both the scientific and popular literature (e.g., Steel 1969; Thulborn 1971a; Colbert 1981; Norman 1985).

Sternberg (1949) also subdivided Ceratopsidae into two lineages, but removed Triceratops from the “short-squamosaled” group by hypothesizing a “long-squamosaled” origin for this genus. Langston (1967), citing characters of the premaxilla, concurred with this reassignment of Triceratops and added Pachyrhinosaurus to the “short-squamosaled” group. Langston's paper marked the first use of a character other than frill length to diagnose ceratopsid subfamilies. The placement of Triceratops within the “long-squamosaled” clade Chasmosaurinae has been upheld by subsequent analyses (e.g., Dodson and Currie 1990; Forster 1990b).

Lehman (1990) revived two of Lambe's (1915) three subfamilies, formally subdividing Ceratopsidae into Chasmosaurinae and Centrosaurinae, a division upheld by all subsequent studies. Recent consideration of historical relationships, including cladistic analyses, within Ceratopsidae include those of Lehman (1990, 1998, Chasmosaurinae), Dodson (1990c, Centrosaurinae), Dodson and Currie (1990, Ceratopsidae), Forster (1990b, Ceratopsidae); Godfrey and Holmes (1995, Chasmosaurus); Sampson (1995, Centrosaurinae), and Penkalski and Dodson (1999, Centrosaurinae). While all these studies support the monophyly of Ceratopsidae, Centrosaurinae, and Chasmosaurinae, the arrangement of taxa within each clade differs among them. Additionally, Penkalski and Dodson (1999) removed Avaceratops from Ceratopsidae, suggesting instead that this genus is the sister to all other ceratopsids.

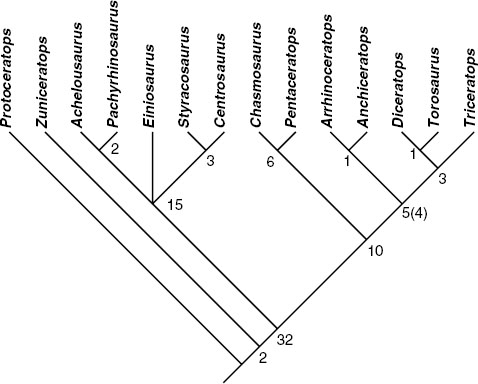

To examine phylogenetic relationships among ceratopsid genera, a cladistic analysis was performed employing 12 ingroup taxa: Achelousaurus, Anchiceratops, Arrhinoceratops, Centrosaurus, Chasmosaurus, Diceratops, Einiosaurus, Pachyrhinosaurus, Pentaceratops, Styracosaurus, Torosaurus, and Triceratops. Outgroups used for this analysis were Protoceratops and Zuniceratops. The data matrix for this study was culled from a more comprehensive, species-level analysis of ceratopsid relationships (Forster and Sampson, in review). The tree presented here was rooted using Zuniceratops and Protoceratops as outgroups. This analysis included 73 cranial and postcranial characters and was optimized using delayed transformations. Multistate characters 17, 29, 31, and 71 were ordered based on ontogenetic information, and all characters were equally weighted. The data were analyzed using PAUP and manipulated in MacClade.

FIGURE 23.8. Cladogram of Ceratopsidae. Adams consensus of three trees (L = 85 steps, CI = 0.906, HI = 0.094, RI = 0.941). Numbers indicate how many synapomorphies are found at each node.

Three most parsimonious trees resulted from this analysis (L = 85 steps, CI = 0.906, HI = 0.094, RI = 0.941), which strongly support the monophyly of Ceratopsidae, Centrosaurinae, and Chasmosaurinae. The instability in these trees is due entirely to ambiguity in the placement of Einiosaurus within Centrosaurinae. Einiosaurus is either the sister to all other centrosaurines, the sister to Centrosaurus-Styracosaurus, or the sister to Achelousaurus-Pachyrhinosaurus. All other taxa remain stable in all trees. The strict consensus tree is identical to the Adam's consensus tree and is shown in figure 23.8.

Zuniceratops, the sister group to Ceratopsidae, possesses characters previously thought to be restricted to Ceratopsidae. In this analysis, two unambiguous characters are pulled down to the Zuniceratops + Ceratopsidae node: the presence of supraorbital ornamentation and a craniocaudally expanded distal coronoid process. The development of supraorbital horns, long thought to be a diagnostic character of Ceratopsidae, occurred prior to the origination of this clade and suggests that long supraorbital horns are primitive for Ceratopsidae. Likewise, the expanded coronoid process of Zuniceratops indicates that this feature preceded the origination of Ceratopsidae. However, the full complement of characters observed in the complex masticatory system of ceratopsids remains only partially developed in Zuniceratops. For example, Zuniceratops still retains single-rooted cheek teeth.

The definition and diagnosis of Ceratopsidae is presented at the beginning of this chapter. Of the two subclades of Ceratopsidae, Centrosaurinae is defined as all Ceratopsidae closer to Centrosaurus than to Triceratops and is diagnosed by ten unambiguous and five ambiguous (where noted) characters: premaxillary oral margin extends below the alveolar margin, the caudoventral premaxillary process inserts into the nasal (ambiguous), postorbital horns less than 15% of the basal skull length, a jugal infratemporal flange, short parietosquamosal frill (0.70 or less than the basal skull length [ambiguous]), parietal marginal imbrication, squamosal much shorter than parietal, squamosal rostromedial lamina, median bar wide (ambiguous), the epoccipital crosses the parietal-squamosal joint (ambiguous), pattern of epoccipital fusion from caudal to rostral, six to eight parietal epoccipitals per side, parietal epoccipital at locus 2 medially directed, parietal epoccipital at locus 3 modified into a large horn (ambiguous), and predentary triturating surface inclined steeply laterally.

Chasmosaurinae, the other subclade of Ceratopsidae, is defined as all members of Ceratopsidae closer to Triceratops than to Centrosaurus. It is diagnosed by ten unambiguous characters: rostral enlarged with a deeply concave caudal margin and hypertrophied dorsal and ventral processes, premaxillary septum, premaxillary narial strut, presence of an interpremaxillary fossa, rostrally elongate premaxillary narial process, keyhole-shaped fontanelle, triangular squamosal epoccipitals, rounded ventral sacrum (sulcus absent), ischial cross section laterally compressed with bladelike dorsal margin, and ischial shaft broadly and continuously decurved.

The basal structure among chasmosaurines is moderately well supported, with the Triceratops (Diceratops + Torosaurus) plus Anchiceratops-Arrhinoceratops clade supported by four unambiguous and three ambiguous (where noted) characters: caudoventral premaxillary process inserts into nasal (ambiguous), nasal ornamentation located over the dorsal or rostrodorsal naris, postorbital ornamentation arises caudodorsal or caudal to orbit, postorbital horns straight or rostrally curved (ambiguous), supracranial cavity deep and complex, frontal fontanelle round to oval, and parietal median bar wide (ambiguous). The Triceratops (Diceratops + Torosaurus) clade is united by three unambiguous synapomorphies: recess in the ventral premaxillary septum, large and deep recess in the premaxillary septum, and recess in the premaxillary narial process. Similarly, the Chasmosaurus-Pentaceratops clade is united by three unambiguous and one ambiguous (as noted) characters: bony flange along the caudal margin of the narial strut, forked distal end of the premaxillary caudoventral process, large parietal fenestrae (45% or more total parietal length), and parietal epoccipital at locus 1 caudally directed (ambiguous).

Although this analysis results in nearly complete resolution among all ceratopsid genera, in some cases the support for lower level relationships is weak. For example, among centrosaurines only one additional step is required to collapse the Achelousaurus-Pachyrhinosaurus clade and two steps are required to collapse the Centrosaurus-Styracosaurus clade. Within chasmosaurines, one additional step is needed to collapse both the Arrhinoceratops-Anchiceratops and Diceratops-Torosaurus node.

The centrosaurine Avaceratops was eliminated from the final analysis because of its subadult status (a number of characters are coded for the adult condition only) and lack of crucial diagnostic morphology (e.g., nasals, postorbitals, and parietal epoccipitals). Nevertheless, Avaceratops shares a number of characters exclusively with Centrosaurinae (e.g., squamosal length and morphology, premaxillary morphology), supporting its placement within this clade.

Historical Biogeography

To date remains of ceratopsids have been confirmed only in western North America (Canada, United States, and Mexico), as has their closest outgroup, Zuniceratops, implying a wholly North American origin and evolution for Ceratopsidae. A third taxon has figured prominently in recent discussions of ceratopsid phylogeny and biogeography—Turanoceratops tardabilis—reported by Nessov et al. (1989) from the Upper Cretaceous (?Coniacian) Bissekty Formation of Uzbekistan. Based on isolated and fragmentary materials, Turanoceratops was reported to include double-rooted teeth and supraorbital horns, leading Nessov (1995) to claim that it was a ceratopsid. Based on his analysis, a number of authors have regarded Turanoceratops as the sister taxon to Ceratopsidae (e.g., Sereno 1997; Chinnery and Weishampel 1998; Wolfe and Kirkland 1998), suggesting that ceratopsids may have had an Asian origin. However, problems with the Turanoceratops material make these interpretations untenable. First, the lack of association among the fragments assigned to Turanoceratops make it impossible to confidently associate this material with a single taxon. Additionally, Makovicky (2002), after reexamining these materials, reported that the teeth are single-rooted as in nonceratopsid ceratopsians, and suggested that the supraorbital horn may conceivably belong to a thyreophoran. He regarded Turanoceratops as a nomen dubium, an assessment that we follow here. Therefore, the origin and evolution of Ceratopsidae is restricted entirely to North America.

Ceratopsids spread widely throughout western North America during the Late Cretaceous. Centrosaurines are best known from more northerly regions, particularly Alberta and Montana, yet their remains have been recovered from as far north as Alaska (Clemens and Nelms 1993) and as far south as New Mexico (Williamson 1997) and Mexico (Sampson, unpublished data). Chasmosaurines were also latitudinally widespread, known from southern Canada down to Mexico.

Taphonomy and Paleoecology

The fossil record of ceratopsids is exceptional, one of the best known for any major group of dinosaurs. All genera are represented by essentially complete skulls, almost all by multiple individuals, and about half by associated skeletal material. Although preservation of solitary individuals is common, numerous examples of low-diversity bone beds, or mass death assemblages, of ceratopsids are known. To date, mass death assemblages of horned dinosaurs have been found in Alberta (Langston 1975; Currie and Dodson 1984; Tanke 1988; Ryan and Russell 1994; Eberth 1996; Ryan et al. 2001b), Montana (Rogers and Sampson 1989; Rogers 1990; Horner et al. 1992), and Texas (Lehman 1989). White et al. (1998) documented occurrences of Triceratops across the spectrum of depositional environments preserved in the Hell Creek Formation, including channel deposits (thalweg, point bar, and toe-of-point bar), floodplain paleosols and ponds, as well as distal levees. However, despite abundant material, monotypic bone beds of Triceratops are not known in the Hell Creek Formation or elsewhere.

Ceratopsid bone beds consist of abundant, disarticulated remains (Langston 1975; Currie 1981, 1987b; Currie and Dodson 1984; Lehman 1989; Sampson 1995; Sampson et al. 1997). Bone-bed assemblages are currently known for Anchiceratops ornatus, “Brachyceratops montanensis,” Centrosaurus apertus, Chasmosaurus belli, C. mariscalensis, Einiosaurus procurvicornis, Pachyrhinosaurus canadensis, an undescribed pachyrhinosaur, and Styracosaurus albertensis (Sternberg 1970; Currie and Dodson 1984; Tanke 1988; Rogers 1990; Horner et al. 1992; Sampson 1995, Sampson et al. 1997; Ryan et al. 2001b). Many of these sites preserve evidence of dozens or hundreds of individuals, and some may have more than 1,000 (Eberth 1996). In virtually all instances, the great majority of elements belong to a single species. While most isolated ceratopsid materials consist of mature individuals whose skulls exhibit partial or complete closure of sutures, bone beds often contain juveniles and subadults, as well as adults. Thus, these mass deaths offer a window into ceratopsid ontogeny, and into the breadth of intraspecific variation generally. Interestingly, while Triceratops is one of the most commonly occurring of all dinosaurs (Dodson 1990c), it occurs primarily as solitaires; no bone beds or evidence of mass death have been reported.

Such remarkable concentrations of bones belonging to a single species suggest that ceratopsids congregated in large, gregarious accumulations that were susceptible to mass mortality. Bone beds in channel deposits indicate that flooding may have been responsible for mass drowning in some cases (Currie and Dodson 1984). Another interpretation is that channel deposits concentrated individuals into large accumulations. Other bone beds, however, occur in overbank or floodplain sediments associated with quiet water environments. Drought is the primary cause of mass death accumulations today (e.g., Corfield 1973; Haynes 1987, 1988), with carcasses of large herbivores often concentrated around waterholes. Evidence of strong seasonality and semiarid conditions in association with ceratopsid bone beds indicates that drought may also have been a major killing agent during the Late Cretaceous (Rogers 1990). Mass bone-bed accumulations have sometimes been interpreted as evidence for herding behavior in ceratopsids (e.g., Currie and Dodson 1984). However, waterholes also may act to concentrate large numbers of individuals of otherwise solitary species during times of drought. Caution, plus knowledge of the taphonomy of each site, must be taken into account before framing such behavioral hypotheses.

There is still a question as to the preferred environment(s) of ceratopsids. They were large-bodied herbivores, and some of the bone-bed evidence suggests that some species may have been gregarious for at least a portion of the year. If so, they probably moved through a range of environments. A number of studies suggest that ceratopsids were more abundant in coastal habitats than inland (Lehman 1987; Brinkman 1990; D. B. Brinkman et al. 1998; but see Lehman 1997). Notably, however, D. B. Brink-man et al. (1998) found that the large, low-diversity ceratopsid bone beds in upper Campanian sediments of Dinosaur Provincial Park, Alberta, occur with much greater frequency in inland deposits. These authors interpreted this result as possible evidence of seasonal movements in response to climate variations. That is, small groups of ceratopsids occupied coastal environments for part of the year and then aggregated in large “herds” to move inland, perhaps in association with nesting.

Functional Morphology, Behavior, and Evolution

Posture and Locomotion

The posture and gait of ceratopsids has proven to be remarkably troublesome (Dodson and Farlow 1997). The first skeletal mounts in museums were those of Triceratops at the U.S. National Museum of Natural History in 1904 and at the American Museum of Natural History in 1923, and of Chasmosaurus at the National Museum of Canada in 1927. In each case, the skeleton was reconstructed with erect, parasagittal hind legs and widely splayed, sprawling fore legs, with humeri oriented nearly horizontally. Sternberg (1927b) and Osborn (1933) were explicit as to why the mounts showed a sprawling pose: the articulations of the bones permitted no other interpretation. In particular, the large humeral head is situated not on the proximal end but wraps to the caudal surface of the proximal humerus, defying attempts to mount it vertically. In addition, the prominent coracoid impedes forward movement (protraction) of the humerus, an action further limited by the large deltopectoral crest.

Many recent artistic renderings of ceratopsids have favored fully erect, columnar posture for the forelimbs (e.g., Bakker 1987; Paul 1987b, 1991b). This pose was first suggested by Marsh (1891d), who reconstructed Triceratops with an erect forelimb in which the shoulder joint was completely disarticulated. After reevaluating ceratopsid forelimb anatomy and biomechanics, Johnson and Ostrom (1995), Dodson (1996), and Dodson and Farlow (1997) argued that anatomical objections to upright, columnar posture remain and that artistic reconstructions do not substitute for actually posing the bones. These authors argued for a semierect forelimb posture with the elbows slightly everted. More recently, based on footprint data and interpretations of bony morphology, Paul and Christiansen (2000) argued that the forelimb of ceratopsids was held with the elbow slightly everted but operated in a nearly parasagittal plane.

Two lines of evidence may in future help resolve the problem of posture: footprints and computer models. Footprints of ceratopsids are rare, but Ceratopsipes goldenensis from Colorado was recently described by Lockley and Hunt (1995b), who claim that the narrow gauge prints confirm upright stance and falsify sprawling stance. Dodson (1996) failed to find the 1.25-m spread of the front feet indicative of narrow gauge. In addition, Dodson and Farlow (1997) emphasized that it is impossible to infer the angulation of the forelimb from shoulder to foot simply from the separation of the front feet in a trackway; a narrow gauge may not imply a columnar stance. Computer manipulation of accurate three-dimensional models of bones offers great promise. These have already been applied to the problem of the mobility of sauropod necks (Stevens and Parrish 1999) and analyses of the kinetics of the skeleton of Triceratops at the Smithsonian Institute (Andersen et al. 1999; Chapman et al. 1999; Jabo et al. 1999). Studies such as these may provide additional evidence of the range of motion permitted at each joint, evidence that is difficult to obtain by physical manipulation of the bones themselves owing to their size, weight, and fragility.

The potential for galloping in ceratopsids also has been explored. For example, Paul and Christiansen (2000) suggested that ceratopsids had a maximum running speed that significantly exceeded that of extant elephants and that they were likely able to attain a full gallop. Conversely, Carrano (1998) studied categories of locomotor habit in dinosaurs and mammals and showed that ceratopsids comprised some of the most “graviportal” of all dinosaurs, possessing robust limb bones, short distal limb segments, and long input muscle lever arms. Although some large graviportal mammals (e.g., bears, rhinos) gallop, others do not (e.g., hippos, elephants). In addition, galloping is not limited to mammals with erect, parasagittal limbs—even semierect crocodilians are known to gallop. Despite speculation regarding galloping in ceratopsids, the correlation between gait and bony morphology remains uncertain.

Feeding, Diet, and Respiration

The jaw system of ceratopsids is highly derived and unique among vertebrates, characterized by massive dental batteries with vertical shear. Ostrom (1964a, 1966) first described the functional morphology of this jaw system. Like hadrosaurs, and unlike all other dinosaurs, ceratopsids possess elongate, highly specialized jaws with tooth batteries and robust, edentulous beaks. In contrast to hadrosaurs, which possessed the capacity for crushing and grinding (Ostrom 1964b; Norman and Weishampel 1985), ceratopsid jaws were restricted to vertical or near-vertical shearing. However, both hadrosaurs and ceratopsids were conservative in the evolution of the masticatory apparatus. Once evolved, the two highly derived feeding systems persisted with only minor modifications until the ultimate extinction of both lineages. The ceratopsid beak is well designed for grasping and plucking rather than for biting (Ostrom 1966). The location of the jaw articulation well below the level of the dentary tooth row, combined with the tall coronoid process (acting as a fulcrum for the jaw adductors), indicates that extremely high bite forces could be generated along the tooth row. The head was held low, so herbaceous plants were probably favored as food (Tait and Brown 1928), although horns and beaks could conceivably have been used to push down taller plants.

An advantage of large body size is the ability to consume lower-quality fodder than small-bodied animals (Demment and Van Soest 1985). Like large mammalian herbivores today, ceratopsids and other dinosaurian herbivores probably had low mass-specific metabolic rates and may have had a gut microflora to aid in the fermentation and digestion of poor quality fodder (Farlow 1987a). Whether ceratopsids were foregut (such as bovids) or hindgut (such as horses) fermenters is unknown, but it is probably unwarranted to apply the browser-grazer continuum used in the description of mammalian diets to dinosaurs. The distinction between browsers and grazers is based primarily on the relative amount of grasses in the diet. As grasses were not available to Mesozoic herbivores, this kind of classification is likely to lead to erroneous conclusions, although it may eventually be possible to describe a browser continuum based on the fodder of herbivorous dinosaurs.