TWENTY-EIGHT

Physiology of Nonavian Dinosaurs

Ever since dinosaurs were first recognized as a distinct group of reptiles, the question of what they were like as living animals has sparked considerable interest. In many respects, dinosaurs were arguably the most successful of all land vertebrates. With their spectacular morphological diversity and impressive size range, they dominated the terrestrial fauna from the Late Triassic to the Late Cretaceous. Their cosmopolitan reign far surpassed that of any other group of tetrapods, including mammals. Not surprisingly, the possible reason for this unparalleled success—their biology—has been the focus of much attention. Dinosaur paleobiology remains a vibrant, exciting, and, more often than not, highly contentious field of research.

Over time, perceptions of dinosaur lifestyle and paleobiology have been altered repeatedly by new insights and interpretations. During the 1820s and 1840s, dinosaurs were generally likened to extant reptiles, only bigger, and they were conventionally portrayed as dimwitted, sluggish, cold-blooded swamp dwellers. Owen (1842b) first challenged these ideas: pointing to postural similarities between dinosaurs and such mammals as elephants and rhinoceroses, he postulated a mammal-like physiology for dinosaurs. Likewise, Huxley (1870) emphasized similarities between Archaeopteryx and small (nonavian) theropod dinosaurs. However, this idea of an elevated metabolic capacity for dinosaurs was short-lived, and most people reverted to the sluggish, reptilian models (Lambe 1917a; Colbert et al. 1946, 1947). These notions were challenged once again in the 1970s, when the similarities between theropods and birds received renewed attention. This “renaissance” view of dinosaurs held that they were dynamic, warm-blooded creatures, essentially comparable with modern mammals and birds (Russell 1965; Ostrom 1970b; Bakker 1972, 1975a, 1975b; Ricqlès 1974, 1980). These reconstructions of hot-blooded dinosaurs were widely embraced and have become firmly entrenched in the popular media. However, they were based, in large part, on the unwarranted assumptions that ectothermy necessarily implies a sluggish, inactive lifestyle, and that only endothermy could account for the dynamic attributes and success of the dinosaurs. Recent decades have seen an increased appreciation of the complex biology of ectotherms (summarized, for example, in an ongoing series of reviews in Biology of the Reptilia). This, combined with a more rigorous approach for assessing the paleophysiology of fossilized organisms, has broadened our understanding of the biology of dinosaurs.

Thermoregulation versus Aerobic Capacity: General Principles

During the past several decades, one of the most contentious issues in dinosaur paleobiology has been their metabolic status: were these animals endothermic (like modern mammals and birds), ectothermic (like extant reptiles and most other vertebrates), or did they possess yet another kind of metabolic physiology? The answer to this question carries many implications for our understanding of the ecology and lifestyles of dinosaurs. In these debates, two distinct issues—thermoregulation and aerobic capacity (i.e., the capacity for sustainable, oxidative metabolism)—are frequently confused. Warm-bloodedness and homeothermy are often uncritically equated with endothermy and elevated metabolic rates, and ectothermy with poikilothermy and cold-bloodedness. This oversimplification fails to recognize the complexities of the thermal ecology of endotherms and, especially, those of ectotherms. In the interest of clarity, we provide the following brief outline of these distinct physiological attributes.

Thermoregulation

Under conventional laboratory conditions, as well as in strongly seasonal, cool-temperate latitudinal zones, differences in the thermal strategies of extant endotherms and ectotherms are obvious. Through high rates of internal heat production, endotherms are able to maintain a constant body temperature over a wide range of ambient thermal conditions, even while at rest. Ectotherms, on the other hand, are usually unable to maintain an independent body temperature under these circumstances, and thus frequently are sluggish even in moderate temperatures. Such sharply contrasting characteristics formed much of the basis for the early reconstructions of sluggish dinosaurs, but they also lie at the core of the notions of the supposed competitive superiority of endotherms and the concept of hot-blooded dinosaurs (Bakker 1968, 1971b, 1975a, 1975b, 1980, 1986).

However, the low resting metabolic rates of extant ectotherms do not preclude the acquisition of high body temperatures or even homeothermy. Under favorable conditions, extant reptiles are capable of maintaining a significant thermal gradient between internal and external environments (Pearson 1954; Schmidt-Nielsen 1990). Many lizards thermoregulate behaviorally during the diurnal activity period, and routinely maintain body temperatures that overlap those of endotherms (see Greenberg [1980] and Avery [1982] for reviews). Larger ectotherms, by virtue of their small surface-area-to-volume ratio and correspondingly low heat loss rates (high thermal inertia), can remain virtually homeothermic in their natural environments (Friar et al. 1972; McNab and Auffenberg 1976; Standora et al. 1984; Paladino et al. 1990).

Extrapolating from such observations, Spotila et al. (1973, 1991; see also Spotila 1980; Paladino et al. 1997; O'Connor and Dodson 1999) have constructed heuristic mathematical models to examine the biophysical constraints of thermoregulation in large animals. These models indicate that thermal inertia increases with increasing body mass. Regardless of metabolic capacity, large-bodied animals tend to become isolated from ambient thermal conditions and attain stable internal temperatures. Consequently, it is not necessary to postulate high, endothermic metabolic rates to achieve homeothermy in most dinosaurs. Over the size range of dinosaurs (2 to >30,000 kg), these models suggest that small individuals (<75 kg) would still be affected by daily temperature fluctuations. However, moderatesized to large dinosaurs (>500 kg) would be essentially unaffected by such changes, and would respond only to fluctuations on a weekly-to-monthly scale, even if these animals were reconstructed with ectothermic metabolic rates. In fact, endothermic metabolic rates would likely have put large dinosaurs (>1000 kg) at risk of overheating, even at moderate temperatures (Spotila et al. 1991; Paladino et al. 1997; O'Connor and Dodson 1999). Note that no particular adaptations, other than large size, are required to attain inertial homeothermy (contra Padian 1997b), although enhanced vascular control of heat loss could refine the thermoregulatory abilities of such animals (Paladino et al. 1990; Paladino and Spotila 1994).

Taking into consideration the comparatively warm and equable climatic conditions of the Mesozoic, Spotila et al. (1973, 1991) and O'Connor and Dodson (1999) conclude that, between behavioral thermoregulation and thermal inertia, ectothermic dinosaurs would have been capable of attaining high body temperatures and remaining homeothermic for extended periods of time. However, at high latitudes during the more seasonal Late Cretaceous, such animals might have had to resort to hibernation or migration. This is not meant to suggest that dinosaurs could not have been endothermic, but to emphasize that, even if they were ectothermic, this by no means implies that they were limited to having low body temperatures or a sluggish lifestyle.

Aerobic Capacity

Although the thermal profiles of endotherms and ectotherms may effectively converge under the right conditions, the fundamental physiological difference between ectotherms and endotherms lies in their aerobic capacities. Endotherms have much higher rates of cellular oxygen consumption: even at rest, mammalian and avian metabolic rates are usually about 5–15 times greater than those of reptiles of the same body mass and temperature (Bennett 1973, 1982, 1991; Bennett and Dawson 1976; Else and Hulbert 1981; Schmidt-Nielsen 1984, 1990). In the field, the metabolic rates of mammals and birds usually exceed reptilian rates by about a factor of 20 (Nagy 1987). To support such high rates of aerobiosis, endotherms have made profound structural and functional modifications to facilitate the assimilation of oxygen in the tissues. Both birds and mammals have highly specialized lungs with greatly increased pulmonary capacity and ventilation rates (Duncker 1978, 1989; Perry 1983), fully segregated pulmonary and systemic circulations, and expanded cardiac outputs (Romer and Parsons 1986; Bennett 1991; Kardong 2002). They also have greatly increased blood volume and blood oxygen carrying capacities (Bennett 1973, 1991; Schmidt-Nielsen 1990), increased mitochondrial density and enzymatic activities (Else and Hulbert 1981, 1985; Ruben 1991, 1995), as well as altered membrane protein and phospholipid content (Ruben 1995).

Unfortunately, however, these key signals of endothermy are not preserved in fossils. Consequently, most previous discussions about the metabolic status of extinct groups have relied primarily on speculative and/or circumstantial evidence, such as predator/prey ratios, fossilized trackways, and paleoclimatological inferences, or on correlations with mammalian or avian morphology, such as posture, brain size, and bone histology. Subsequent reviews of these approaches have revealed that virtually all of these arguments are equivocal, at best (Bennett and Dalzell 1973; Bennett and Ruben 1986; Farlow 1990; Chinsamy 1994; Farlow et al. 1995a).

Fisher et al. (2000) describe evidence of what they claim is a fossilized four-chambered heart with a fully partitioned ventricle in Thescelosaurus. These authors suggest that the absence of a foramen of Panizza between the ventricles and the presence of a presumed single aortic arch argue for an intermediate or higher metabolic rate in this ornithischian. However, in addition to lingering questions about nature of the concretion (Morell 2000; Stokstad 2000), several anatomical errors and questionable assumptions cast serious doubts on this interpretation. Contrary to the authors' assumptions, the ventricles of extant crocodilians are, like those of birds, fully separated; the foramen of Panizza is located at the base of the aortic arches and not between the ventricles (Goodrich 1930; White 1968, 1976; Franklin et al. 2000). A four-chambered heart is thus present in both crocodilians and birds, and its presence among dinosaurs is not only a safe inference, it is also not informative about possible metabolic rates of these animals. The presence of a single aortic arch would have been more diagnostic, but the authors cannot substantiate that only one arch was present. As neither the pulmonary arteries nor the carotids are preserved (Fisher et al. 2000), it is clear that the cardiovascular complex is in completely preserved. Significantly, its left side, where the “missing” aortic arch would most likely have been, was lost to erosion. Consequently, this material provides little, if any, insight into the metabolic physiology of these animals.

Recently, the oxygen isotopic (O16/O18) composition of fossilized bone phosphate has been used to assess the thermal physiology of dinosaurs (Barrick and Showers 1994, 1995; Barrick et al. 1996, 1997). The preserved isotope ratios purportedly reflect in vivo body temperatures, and the apparent lack of intrabone and especially interbone variation in a variety of dinosaurs was presumed to signal the presence of homeothermy and high metabolism. Unfortunately, in addition to uncertainties regarding the stability of bone oxygen isotopes during the fossilization process (Hubert et al. 1996; Kolodny et al. 1996), several assumptions render these conclusions doubtful. First, as Reid (1997b) also pointed out, Barrick and Showers (1994, 1995) and Barrick et al. (1996, 1997) assumed that bone deposition rates are equally continuous in the different bones compared. However, the variable distribution of rest lines (annuli or lines of arrested growth [LAG]; see below) reported among different bones of many dinosaurs (Reid 1990, 1996) indicates that this assumption is often not supported. Second, Barrick and Showers (1994) and Barrick et al. (1996, 1997) incorrectly apply a definition of homeothermy, which delimits only the temperature fluctuations of body core (Bligh and Johnson 1973), to thermal variation between the body core and the extremities. In fact, extant endotherms are typically a thermal mosaic, and the temperatures of their extremities are routinely closer to ambient temperatures (Scholander 1955; Schmidt-Nielsen 1990). This means that, in particular, interbone temperature variations have no bearing on homeothermy. Third, these authors assume that homeothermy can only be accounted for through endothermic physiology; this assumption has been repeatedly falsified (see above). Consequently, these studies on oxygen isotopes of dinosaur bone reveal little, if any, definitive information about dinosaur metabolic status.

When discussing dinosaur physiology, several additional points are worth bearing in mind. The first is that endothermy is a derived attribute convergently found in mammals and birds (Gauthier et al. 1988b; Kemp 1988), whereas ectothermy is the primitive condition for vertebrates (Crompton et al. 1978; Bennett and Ruben 1979; Bennett 1991; Ruben 1995; Farmer 2001). This implies that in the case of extinct taxa, such as dinosaurs, in which the metabolic status is in question, it is inherently more conservative to infer ectothermy as the primitive condition until an unambiguous argument can be made for a departure from this state to a derived condition. Most workers agree that the closest living relatives of dinosaurs include (ectothermic) crocodilians and (endothermic) birds, although the exact nature of the evolutionary relations between birds and dinosaurs remains controversial (Burke and Feduccia 1997; Feduccia 1999; Dodson 2000). We take no position in these phylogenetic discussions, but point out that if nonavian dinosaurs are bracketed by extant birds and crocodilians, arguments for a derived, birdlike metabolic status must necessarily be founded on so-called “level II inferences” (Witmer 1995a). Such inferences require explicit identification of preserved attributes that have strong, causally linked functional associations with markedly elevated resting metabolic rates before presence of endothermy may be inferred. Based solely on the hypothesized close phylogenetic affinity of birds and theropod dinosaurs, Padian and Horner (2002, this vol.) have argued that endothermic features must have evolved in nonavian theropods or a broader ancestral group. This would be a legitimate inference only if basal birds (e.g., Archaeopteryx, Rahonavis, Patagopteryx, Vorona, Confuciusornis) had already achieved full endothermic status, a conclusion that has never been established and one that has repeatedly been disputed (Ruben 1991; Chinsamy et al. 1994; Chinsamy 2000, 2002; Jones and Ruben 2001). The evolution of endothermy, with its many requisite structural and functional modifications, was likely a protracted process of gradual, cumulative physiological and morphological improvements (see also Bennett and Ruben 1979; Ruben 1995). However, questions of when endothermic attributes were acquired in any evolutionary lineage can only be answered with positive evidence of osteological, or at least fossilizable, functionally linked attributes of this derived physiological status. Until such evidence is revealed, the case for endothermic dinosaurs must be considered unsubstantiated.

The second point to bear in mind is that considerable variation in metabolic capacity often does exist among conspecific individuals and populations, among closely related species, and among families and orders within classes (Nagy et al. 1984; Ruben 1995); such variation is often strongly correlated with dietary habits (McNab 1986a, 1986b, 1988). However, as O'Connor and Dodson (1999) point out, such differences are comparatively minor relative to the 5–15-fold differences that exist between extant endotherms and equivalent-sized reptiles (Bennett and Dawson 1976; Else and Hulbert 1981). Even the low basal metabolic rates of monotremes, when corrected for the low temperature set point of these animals (accounting for Q10 effects), are within 5% of the mean for all mammals and nonpasserine birds (Schmidt-Nielsen 1984). Although the reasons for such highly conserved metabolic rates remain poorly understood, it seems likely that the suite of attributes that support a particular metabolic strategy is under strong intrinsic constraint (Taylor and Weibel 1981; Weibel 2000). For example, a highly modified lung cannot provide much metabolic benefit (i.e., is not selectively advantageous) unless the circulatory system and the cellular physiology are adjusted to process the additional oxygen. Such physiological and morphological constraints would tend to restrict the ability of closely related taxa to have greatly divergent metabolic rates. It is therefore unlikely, for instance, that iguanodontids would have a profoundly different metabolic status than hadrosaurids. Nor is it likely that taxa could have switched from endothermy early in life to ectothermy at maturity (as suggested by Horner and Lessem [1993]), or alternated seasonally between these two states (as suggested by Farlow [1990]). True, many small mammals and some birds can, under certain circumstances, avoid unfavorable conditions by opting out of high-cost endothermic metabolism and go into torpor or hibernation, and some larger mammals, such as some bears, also maintain lower-than-normal body temperatures during a “winter sleep” (Schmidt-Nielsen 1990; Randall et al. 2002). However, none of these animals maintains activity during these highly specialized and tightly regulated avoidance behaviors: no extant forms alternate between ectothermic and endothermic modes while remaining active.

Finally, one of the principal factors affecting metabolic rates—aside from metabolic status—is body mass. Large animals, because of their greater volume of metabolizing tissues, inherently have greater overall metabolic rates than small mammals, even at rest. However, per unit mass, the tissues of the larger animal consume less oxygen than those of the smaller animal; mass-specific basal metabolic rates are therefore higher in small animals than in larger ones. Again, the underlying physiological causes for this somewhat counterintuitive scaling phenomenon are not clear (for a discussion, see Schmidt-Nielsen [1990], Darveau et al. [2002], and Randall et al. [2002]), but this relationship has been documented for all vertebrate and invertebrate animal groups (Hemmingsen 1960), and almost certainly applied to dinosaurs as well (Reid 1997b). Padian and Horner (2002, this vol.) were thus correct in stating that small theropods most likely had higher mass-specific basal metabolic rates than did large forms. However, this has no implication for the metabolic status of these animals (see also Reid 1997b): scaling alone cannot make small theropods move closer to endothermic levels than large ones. Large mammals are not less endothermic than small ones, and small crocodilian species are no closer to an avian metabolic status than are the larger species.

To understand the physiological and functional aspects of dinosaurs, we also rely on pattern matching (Coombs 1990a). This involves analytical comparisons with their extant relatives (birds, crocodilians, and other sauropsids), as well as comparisons with mammals when considering other aspects of pattern matching, such as their closest living morphological equivalents, closest living ecological equivalent, and their closest living behavioral equivalent.

A number of reviews of nonavian dinosaur physiology have been published in recent years (Farlow 1990; Farlow et al. 1995a; Padian 1997b; Reid 1997b), and to avoid a reiteration of these works, we will not revisit these earlier arguments. However, several new approaches and recent discoveries of soft tissues in nonavian dinosaurs have shed additional light on the physiology of these animals. In this chapter, we look specifically at new evidence pertaining to dinosaur energetics and thermoregulation.

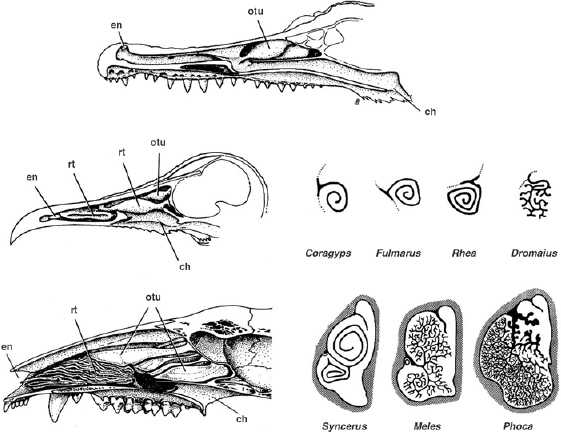

FIGURE 28.1. Nasal passages of extant amniotes. Reptiles, such as crocodilians (top), have up to three simple nasal conchae, all of which are exclusively covered with olfactory epithelium. In contrast, birds (center left) and mammals (bottom left) possess additional complex respiratory turbinates. Cross sections of the respiratory turbinates of representative birds (center right) and mammals (bottom right) are also shown. (Modified from Hillenius 1994.)

Respiratory Turbinates and Resting Metabolic Rates in Nonavian Dinosaurs

Function of Respiratory Turbinates in Extant Amniotes

Nasal turbinates, or conchae, are convoluted bony or cartilaginous projections from the walls of the nasal cavity. These structures are found in most modern amniotes, and range in complexity from comparatively simple curls in reptiles to elaborately scrolled or branched structures in birds and mammals (fig. 28.1). The turbinates are covered with moist epithelia and principally serve to increase the surface area available to these membranes.

Two distinct kinds of turbinates—olfactory and respiratory—are recognized in extant amniotes. These are distinguished by the kind of epithelium they bear, as well as their location in the nasal cavity (Parsons 1971; Hillenius 1994). Olfactory turbinates are nearly ubiquitous among amniotes. These are lined with olfactory sensory epithelium and are generally situated outside the main path of respiratory air. They function specifically to enhance the sense of smell, and are unrelated to metabolic physiology (Hillenius 1994). In contrast, respiratory turbinates are found only among birds and mammals; they are completely absent in all modern reptiles. In both mammals and birds, the respiratory turbinates project directly into the main nasal air stream, are covered exclusively with non-sensory respiratory epithelium, and have a distinct functional association with endothermy (Hillenius 1992, 1994; Ruben 1996; Geist 2000).

Among birds and mammals, chronically elevated rates of lung ventilation (a consequence of having elevated rates of metabolism even while resting—a key attribute of endothermy) could result in potentially deleterious desiccation and heat loss rates, as large volumes of warm, humid air are expelled from the lungs. However, respiratory turbinates provide a compensatory mechanism by absorbing a substantial portion of the heat and moisture contained in respiratory air through a mechanism of intermittent countercurrent exchange (Jackson and Schmidt-Nielsen 1964; Schroter and Watkins 1989; Hillenius 1992, 1994; Geist 2000). In the absence of such a recovery mechanism, respiratory heat and water loss rates associated with continuously high rates of oxidative metabolism and lung ventilation would likely exceed tolerable levels, and endothermy itself might well be unsustainable (Hillenius 1992; Ruben 1995; Geist 2000). Significantly, total surface area of the respiratory turbinates in both mammals and birds scales proportionately with mass-specific resting metabolic rates—both are proportional to body mass0.75 (Owerkowicz and Crompton 2001).

Respiratory turbinates are present in all extant nostrilbreathing terrestrial mammals and birds; they are reduced or absent only in extremely rare cases, most of which occur in aquatic specialists, such as whales, cormorants, and pelicans (Hillenius 1994; Ruben et al. 1996). The widespread presence of respiratory turbinates among extant endotherms strongly suggests that it is very difficult for these animals to circumvent the need for these structures through alternative sites or mechanisms for water recovery. Note that, energetically, respiratory turbinates are comparatively cheap to operate: the countercurrent exchange mechanism incurs no physiological energy expense (Collins et al. 1971). This contrasts sharply with potential alternative water recovery mechanisms, such as salt glands or enhanced kidney function, which require significant, and continuous, investments of cellular energy to function (Schmidt-Nielsen 1990; Randall et al. 2002). Maintenance of a countercurrent exchange mechanism in any portion of the respiratory tree other than the nasal cavity would be untenable: such exchange sites in the body cavity would necessarily preclude deepbody homeothermy, and the presence of such a system in the trachea would likely interfere with the stability of brain temperatures, because of the proximity to the brain-bound carotid arteries (Ruben et al. 1997b; Jones and Ruben 2001). The fact that deep nasopharyngeal temperature virtually equals core body temperature in extant mammals (Ingelstedt 1956; Jackson and Schmidt-Nielsen 1964; Proctor et al. 1977) and birds (Geist 2000) confirms that little or no heat exchange takes place in the trachea. Finally, the widespread presence of respiratory turbinates among extant mammals and birds also indicates that these structures are likely a plesiomorphic attribute for each of these groups (Hillenius 1992, 1994; Geist 2000); all cases of turbinate reduction or absence among these taxa clearly represent secondary, specialized developments.

In contrast to the nearly ubiquitous presence of respiratory turbinates in endotherms, these structures are entirely absent in all extant ectotherms (Parsons 1971), nor are there other modifications of the nasal cavity designed specifically for the recovery of respiratory water vapor. Lung ventilation rates of these animals are sufficiently low that respiratory heat and water loss rates seldom create problems (Geist 2000; Randall et al. 2002). Note that nasal heat exchange and modest recovery of respiratory moisture do occur in thermoregulating reptiles (Murrish and Schmidt-Nielsen 1970; Schmidt-Nielsen 1984). However, without complex respiratory turbinates, the simple nasal passages of ectotherms are effective only at low ventilation rates; for the chronically higher rates of metabolism and ventilation characteristic of mammalian and avian endothermy, specialized respiratory turbinate systems are necessary for complete heat and water exchange (Jackson and Schmidt Nielsen 1964; Schroter and Watkins 1989; Hillenius 1992, 1994; Geist 2000).

Recent embryological and anatomical studies confirm that the respiratory turbinates are neomorphic structures in mammals and birds, which arose independently in each lineage (Witmer 1995b). The most parsimonious conclusion is that these structures evolved in concert with expanding metabolic and lung ventilation rates and the origin of endothermy (Hillenius 1994). Consequently, the presence or absence of respiratory turbinates among fossil amniotes may be a good indicator of the minimal routine, resting ventilation rates and, by extension, metabolic rates of these taxa (Hillenius 1994; Ruben et al. 1996; Jones and Ruben 2001). In other words, respiratory turbinates are exactly the kind of attribute to look for to corroborate a level II inference of endothermy, particularly in those animals often thought to represent the evolutionary precursors to extant endotherms.

Were Respiratory Turbinates Present among Nonavian Dinosaurs?

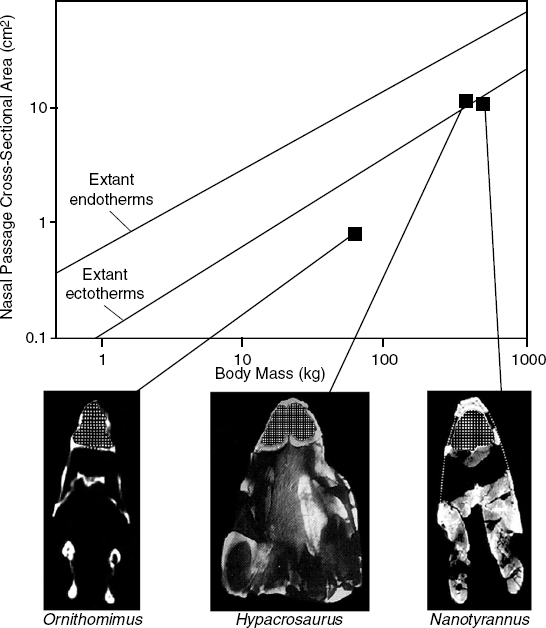

Although turbinates are occasionally found preserved in the fossil record (olfactory turbinates in phytosaurs [Camp 1930], and both respiratory and olfactory turbinates in early mammals [Lillegraven and Krusat 1991]), the fragile nature of the turbinates usually precludes their preservation in fossils. Furthermore, although they ossify or calcify in many extant taxa, the turbinates often remain cartilaginous in birds, further decreasing their chances for preservation. However, Ruben et al. (1996) point out that a correlation exists between the presence of respiratory turbinates in extant mammals and birds and a marked expansion of the proportionate cross-sectional area of the respiratory portion of the nasal cavity (cavum nasi proprium; fig. 28.2). Complex respiratory turbinates form a significant resistance to airflow in the nasal passage of endotherms, which already have elevated ventilation and nasal airflow rates compared with equivalent-sized ectotherms. The expansion of the nasal passages in endotherms noted by Ruben et al. (1996) probably serves to ameliorate problems associated with resistance to airflow, thereby keeping the energetic cost of ventilation to a minimum (Kao 1972; West and Jones 1975; Staub 1991).

Computed tomography (CT) scanning techniques have greatly facilitated the noninvasive study of the nasal passages of dinosaurs, especially of incompletely prepared material, in which traces of the fragile turbinates might still be preserved. Ruben et al. (1996) used CT techniques to examine the nasal regions of Nanotyrannus, Ornithomimus, and Hypacrosaurus. In all three cases, they found no evidence of preserved respiratory turbinates, although remnants of olfactory turbinates were clearly present in the caudal region of the nasal cavity of Nanotyrannus. Moreover, the scans revealed that in the two theropods, large maxillary sinuses occupied a considerable portion of the rostrum and restricted the respiratory portion of the nasal cavity to a narrow, tubular passage (fig. 28.2). There is no sign of an expanded cavum nasi proprium similar to that of mammals or birds; in fact, the proportional diameter of this region in these theropods is virtually identical to that of extant ectotherms (fig. 28.2). Jones and Ruben (2001) point out that similar maxillary sinuses were also present in other tetanuran theropods (and in many nonornithurine birds; Witmer 1997a, 1997b); presumably their respiratory passages were similarly restricted.

Two separate conclusions may be derived from these observations (Ruben et al. 1996; Jones and Ruben 2001): (1) without preserved respiratory turbinates, there is no concrete evidence to corroborate a level II reconstruction of avianlike, markedly elevated resting ventilation rates for these theropods; and (2) the restricted dimensions of the respiratory passage suggest that not only were such turbinates not preserved in the fossils, they were most likely also absent in life. If so, this suggests that chronic respiratory water loss was not a significant problem for these animals, and that resting ventilation rates were probably low compared with modern avian rates. It is possible that the resting ventilation rates of some or all nonavian theropods were modestly higher than most reptilian rates, but not yet so high as to warrant compensatory mechanisms to control respiratory water loss. However, at present, there is no positive evidence to confirm that resting ventilation rates of any nonavian theropods had expanded significantly beyond those of extant reptiles. Note that these observations reveal little about the capacity for maximal ventilation rates and oxygen consumption during periods of activity.

Hypacrosaurus had a similar narrow, ectotherm-like nasal passage (fig. 28.2), and, as in the nasal passages of the theropods discussed above, there is no reason to believe it contained respiratory turbinates (Ruben et al. 1996). In the supracranial crest, the upper end of the lambeosaurine nasal passage, including that of Hypacrosaurus, comprises a complex of curved passages and blind diverticula (Lambe 1920; Weishampel 1981a), but these relate to olfactory functions (Horner et al. 2001) and possibly to sound production (Weishampel 1981b, 1997). Analogously, several other ornithischian groups (ceratopsids, hadrosaurine ornithopods), as well as many sauropods, have made extensive modifications to their narial regions, often resulting in enormously expanded narial fossae. Interestingly, in every case, these are independently derived developments, as they are lacking in the basal members of each clade (Dodson and Currie 1990; Weishampel et al. 1993; Upchurch 1995). Although Witmer (2001a) emphasized that the fleshy nostril was most likely located far forward in the bony narial opening or fossa in all dinosaurs, which places the full length of the narial apparatus in the nasal airstream, the functional significance of the expanded narial regions of the forms mentioned remains unclear. A variety of functions have been proposed, including visual or acoustic signaling (Hopson 1975b), excretory functions (Osmólska 1979; Whybrow 1981), and heat exchange associated with brain cooling (Wheeler 1978), but none of these proposals has been corroborated. At present, there is no particular reason to suspect that the expanded narial regions were associated with reducing respiratory water loss in association with elevated resting metabolic rates: in both extant mammals and birds, these functions are invariably performed by the turbinates in the cavum nasi proprium, and the contribution of the narial region is minimal. However, an analogous development of a narial conchal complex also cannot be completely ruled out either; clearly, this is an area deserving of more attention (Witmer and Sampson 2000; Witmer 2001b).

FIGURE 28.2. Relation of the cross-sectional area of the respiratory nasal passage (cavum nasi proprium) to body mass in extant endotherms (birds and mammals) and ectotherms (lizards and crocodilians), and three genera of Late Cretaceous dinosaurs Hypacrosaurus, Nanotyrannus, and Ornithomimus. Stippled areas in the inset CT cross sections through the rostrum indicate the nasal passages. The data from the dinosaurs were not used in regression calculations. (Modified from Ruben et al. 1996.)

Lung Structure, Ventilation, and Elevated Active Metabolic Rates

In both mammals and birds, highly modified lungs capable of sustaining high rates of respiratory gas exchange support the high aerobic activity capacity associated with endothermy. Both lung morphology and ventilatory mechanisms of endotherms are distinct from those of ectotherms, although birds and mammals follow two fundamentally different patterns. In this light, information on dinosaurian lung structure can provide direct clues about the activity capacity of these animals. Several recent discoveries have yielded surprising new insights into the way dinosaurs may have lived and breathed.

Lungs of Extant Amniotes

Mammals have bronchioalveolar lungs, whereas reptiles and birds have septate lungs. The mammalian respiratory system consists of a hierarchical system of branching air passages (the respiratory tree). The single trachea divides into two bronchi, which in turn subdivide into bronchioles. These further subdivide 20 or more times, ultimately yielding over a million or more tubes, which end in highly vascularized, thin-walled sacs called “alveoli” (approximately 10 microns in diameter). The alveoli are distributed homogeneously throughout the lung and cumulatively provide a large respiratory surface area (Duncker 1978, 1989; Perry 1983). As a result, mammalian lungs have a comparatively high anatomical diffusion factor (ADF), a mass-specific measure of the ratio of total vascularized pulmonary respiratory surface area to mean pulmonary blood-gas barrier thickness. For comparative purposes, ADF is a useful index for the maximal gas exchange capacity of the lung (Duncker 1989). Ventilatory airflow in the mammalian lung is bidirectional (i.e., air flows in and out of the alveoli, but not through them), and each alveolus functions in a bellows-like manner. During inhalation, individual alveoli fill passively under negative intrapulmonary (alveolar) pressure generated by costal expansion and/or diaphragmatic contraction. Exhalation occurs largely as a result of increased intrapulmonary pressure, caused by the elastic recoil of the alveoli. Consequently, during the respiratory cycle, each alveolus participates actively in gas exchange as well as in ventilation. This combination of attributes enables the mammalian lung to sustain the high maximal rates of oxygen consumption associated with extended periods of aerobic exercise in endotherms.

The lung morphology of modern sauropsid amniotes differs fundamentally from the bronchioalveolar lungs of mammals. Further differences in lung morphology occur between avian and nonavian sauropsids. The lung of nonavian sauropsids is comparable with a single, oversized mammalian alveolus at the end of a single bronchus. Septal ingrowths finely partition the wall of the lung into a system of vascularized, honeycomb-like cells called “ediculae” or “faveoli”; in many reptiles, a second generation of larger septae subdivides the lumen of the lung into two or more chambers (Duncker 1978, 1989; Perry 1983). Respiratory exchange occurs principally on the walls of the ediculae/faveoli, but these are generally less well vascularized than the mammalian alveoli. Total respiratory surface area is significantly less than that of similar-sized mammals and birds, and reptilian septate lungs have comparatively low ADF values (Perry 1983; Duncker 1989). As a result, reptilian lungs are intrinsically limited, compared with those of mammals and birds, in their capacity for gas exchange (Ruben et al. 1997a, 1998b). These limitations may be partially circumvented through increased ventilation (Hicks and Farmer 1998, 1999), but here reptiles face additional constraints.

As in mammals, ventilatory airflow in reptilian lungs is bidirectional, but unlike the mammalian alveoli, the respiratory ediculae or faveoli have only limited elastic recoil properties and therefore contribute little to the movement of air during inhalation or exhalation (Duncker 1978; Perry 1983). Instead, respiratory gases move in and out of the ediculae/faveoli primarily through diffusion (Duncker 1978, 1989). In partial compensation, many reptiles maintain a large part of the lung as a less vascularized, but more compliant region, whose primary function is to assist in ventilation of the vascularized portions, resulting in a functionally and morphologically heterogeneous, multichambered lung system (Duncker 1978; Perry 1983). The total lung volume of reptiles, therefore, usually exceeds that of similar-sized mammals and birds (Tenney and Tenney 1970; Perry 1983). However, lung volume is itself constrained by the presence of other organ systems in the abdominal cavity, and the volume of reptilian septate lungs cannot be expanded sufficiently to attain gas exchange rates equivalent to those of mammals and birds. Furthermore, most terrestrial reptiles have a mechanical constraint on lung ventilation during locomotion, because the locomotor action of their costal musculature interferes with its ventilatory action (Carrier 1987, 1991). No extant reptile is capable of achieving maximal aerobic respiratory exchange rates greater than about 15%–20% of those of most endotherms (Hicks and Farmer 1998, 1999; Ruben et al. 1998b). Even in a best-case scenario based on hypothetical improvements of the circulatory system and optimized pulmonary diffusion capacity, the reptilian septate lung attains no more than 57% of these rates, and thus barely overlaps with some of the less active mammals (Hicks and Farmer 1998, 1999; Ruben et al. 1998b). The nonavian septate lung is inherently constrained from supporting respiratory exchange that is consistent with maximal aerobic metabolic rates of active endotherms.

Birds, like all sauropsids, also possess septate lungs, but avian lungs are highly modified from those of their sauropsid ancestors (Duncker 1971, 1974; Perry 1983, 1992). The avian trachea divides into two bronchi; however, each bronchus continues through the lung and connects with the cranial and caudal air sacs. The intrinsic limitations on gas exchange of the reptilian septate lung are circumvented in birds by modifying the dorsal edicular/faveolar portions into a system of narrow, parallel tubes called “parabronchi.” Along their length, the parabronchi give off numerous air capillaries (1 micron in diameter, and thus much smaller than the mammalian alveoli). The air capillaries intertwine with blood capillaries and are the sites for gas exchange (King 1966; Duncker 1971, 1972, 1974; Perry 1983; McLelland 1989a). The total surface area of the vascularized portions of the lung is comparable to or greater than that of a similar-sized mammal, and as a result, the ADF of most avian lungs usually exceeds even that of mammals (Perry 1983, 2001; Duncker 1989; Powell 2000). To prevent collapse of the air capillaries, the respiratory portion of the lung must remain rigid and is therefore firmly attached to the dorsal portion of the ribcage (Duncker 1978, 1989). Air is drawn into the lungs by expansion and contraction of the air sacs (derived from the nonvascular pulmonary chambers of the ancestral reptilian lung [Duncker 1978; Perry 1983, 1992]) that surround the lung and act as bellows (Bretz and Schmidt-Nielsen 1971, 1972; Powell and Scheid 1989; Scheid and Piiper 1989). In the paleopulmo (the main portion of the lung), airflow through the parabronchi is unidirectional. Many birds, especially Passeriformes, have, in addition, a smaller neopulmonic region, in which the parabronchi are less highly organized, and in which airflow appears to be bidirectional (Duncker 1971, 1972, 1974; Perry 1983, 1992; Maina 1989). The unique pattern of air flow through open-ended parabronchi in both the paleopulmo and neopulmo portions of the lung allows a crosscurrent flow of air and blood in the lung; air passes through the parabronchial lung in a caudal-to-cranial direction, and because blood moves in a generally perpendicular direction, it continuously meets air with a high oxygen content (Tucker 1968; Scheid 1979; Piiper 1989). Crosscurrent gas exchange is more efficient than alveolar gas exchange, and this attribute is largely responsible for the high oxygen-extraction capacity of the avian lung and the high capacity for oxygen consumption characteristic of avian physiology, despite the small avian lung volume (Piiper and Scheid 1972, 1975, 1982; Scheid and Piiper 1972; Morgan et al. 1992; Maloney and Dawson 1994; Powell 2000).

Ventilation

Extant amniotes utilize a variety of musculoskeletal mechanisms to ventilate their lungs. Lizards and snakes tend to rely on simple costal ventilation, in which alteration of intrapulmonary pressure results from expansion and contraction of the ribcage; presumably, this is the primitive condition of pulmonary ventilation for tetrapods (Gans 1970; Carrier 1987). Some lizards augment costal ventilation with contractions of the throat musculature during and after bouts of vigorous activity (Brainerd and Owerkowicz 1996; Owerkowicz et al. 1999).

Costal action also contributes to lung ventilation in mammals and crocodilians. However, both crocodilians and mammals rely extensively on active, diaphragm-assisted lung ventilation, whereby a transverse septum, or diaphragm, completely divides the visceral cavity into pleuropericardial and abdominal regions. In mammals, the diaphragm is itself extensively muscularized, and its contraction results in expansion of the pleural cavity and filling of the lungs (Ruben et al. 1987; Bramble and Jenkins 1993). In contrast, the crocodilian diaphragm is nonmuscular and consists of a sheet of connective tissue that closely adheres to the cranial surface of the liver. Inspiratory movement is provided by pairs of longitudinal muscles that extend from the lateral edges of the liver to the pubis, the caudal gastralia, and the preacetabular process of the ischium. Contraction of these diaphragmatic muscles results in a pistonlike caudal displacement of the liver-diaphragm complex, which inflates the lungs (Gans and Clark 1976; Ruben et al. 1997a).

Birds, like lizards, rely principally on costal lung ventilation and lack a mammal-like or crocodilian-like diaphragm. However, the ribcage and sternum of birds are highly modified to facilitate ventilation of the abdominal air sacs. Avian ribs possess a unique system of synovial intercostal and sternocostal joints, which allows a pendulum-like movement of the sternum and shoulder girdle in the sagittal plane. Significantly, the distal end of each sternal rib is transversely expanded and forms a robust hinge joint with the thickened craniolateral border of the sternum. Costal action results in a dorsoventral rocking motion of the caudal end of the enlarged sternum, which expands and contracts the air sacs (King 1966; Schmidt-Nielsen 1971; Brackenbury 1987; Fedde 1987). These characteristics are present even in flightless birds (Schmidt-Nielsen 1971).

Lung Structure and Ventilation in Nonavian Dinosaurs

Among extant tetrapods, the bronchioalveolar lung is unique to mammals, and the repeated subdivisions of the embryonic respiratory diverticulum that are its ontogenetic foundation (Feduccia and McGrady 1991) are apparently an apomorphic attribute of the synapsid clade. Given their affinity to sauropsid amniotes, it is reasonable (a level I inference) to infer that dinosaurs possessed some form of septate lung. Moreover, because dinosaurs are phylogenetically bracketed by crocodilians and birds, it is likewise reasonable (also a level I inference) to infer a complex, heterogeneous, multicameral lung for these animals (Perry 1983, 1992, 2001). The question, however, is whether there is enough evidence to support a level II inference of highly derived, birdlike lungs (i.e., highly heterogeneous parabronchial lungs with crosscurrent gas exchange and an extensive abdominal air-sac system). Alternately, did dinosaurs retain unmodified—crocodilian-like—multicameral lungs?

No fossilized lung tissues have yet been documented, so reconstructions of dinosaurian lungs must rely on indirect evidence. A level II inference of highly derived, avian-like parabronchial lungs for nonavian dinosaurs thus requires osteological correlates of the presence of an extensive abdominal air-sac system, necessary for effective crosscurrent gas exchange (Powell 2000; Perry 2001). Perry (1992, 2001) suggests that the potential for crosscurrent exchange may have been present in ancestral archosaurian lungs, as it is in those of extant crocodilians. However, this does not mean that crosscurrent gas exchange was in fact already manifested in nonavian dinosaurs (as asserted by Perry [2001]). The postulated modifications (Perry 1983, 1992) could, for example, just as easily have taken place within birds.

The thoracic skeleton of nonavian dinosaurs lacks the morphological adaptations associated with the parabronchial lung/abdominal air-sac system of modern birds. Avian-like jointed or hinged ribs are absent in all nonavian dinosaurs, and there is no indication of specialized sternocostal mechanism, such as that which ventilates the abdominal air sacs in extant birds. Ossified sternal ribs are documented for Apatosaurus (Marsh 1883; McIntosh 1990a), and several theropod taxa, including oviraptorids (Clark et al. 1999), ornithomimosaurs (Pelecanimimus; Hillenius, pers. obs.), and dromaeosaurids (Ostrom 1969a; Norell and Makovicky 1999), but in each case, the sternal ribs lack the distinct, transversely oriented distal expansions that form the sternocostal joints characteristic of the avian thorax. The sternal plates of dinosaurs, which are known from a variety of taxa, including ankylosaurs (Coombs and Marya ska 1990), ornithopods (Norman 1980; Foster 1990; Weishampel and Horner 1990), ceratopsians (Sereno and Chao 1988), sauropodomorphs (Young 1947; McIntosh 1990), as well as oviraptorids (Barsbold 1983a, 1983b; Clark et al. 1999), ornithomimosaurs (Pérez-Moreno et al. 1994), and dromaeosaurids (Barsbold 1983a, 1983b; Norell and Makovicky 1997, 1999; Xu et al. 1999b; Burnham et al. 2000), are generally short, and in all cases, lack the thickened lateral border and the transversely oriented hinge joints for the sternal ribs that characterize the sterna of all extant birds. The sternal plates of the immature dromaeosaurid Bambiraptor are exceptionally long, but its lateral edges, including the regions where the sternal ribs articulated, are described as thin (Burnham et al. 2000). By themselves, simple articulations between sternum and sternal ribs cannot be considered diagnostic for any particular lung morphology or ventilatory mechanisms; such articulations between ribs and sternae occur in most amniotes, including lepidosaurs, crocodilians, and mammals (Romer 1956).

ska 1990), ornithopods (Norman 1980; Foster 1990; Weishampel and Horner 1990), ceratopsians (Sereno and Chao 1988), sauropodomorphs (Young 1947; McIntosh 1990), as well as oviraptorids (Barsbold 1983a, 1983b; Clark et al. 1999), ornithomimosaurs (Pérez-Moreno et al. 1994), and dromaeosaurids (Barsbold 1983a, 1983b; Norell and Makovicky 1997, 1999; Xu et al. 1999b; Burnham et al. 2000), are generally short, and in all cases, lack the thickened lateral border and the transversely oriented hinge joints for the sternal ribs that characterize the sterna of all extant birds. The sternal plates of the immature dromaeosaurid Bambiraptor are exceptionally long, but its lateral edges, including the regions where the sternal ribs articulated, are described as thin (Burnham et al. 2000). By themselves, simple articulations between sternum and sternal ribs cannot be considered diagnostic for any particular lung morphology or ventilatory mechanisms; such articulations between ribs and sternae occur in most amniotes, including lepidosaurs, crocodilians, and mammals (Romer 1956).

The presence of avian-like uncinate processes (caudodorsal projections on the thoracic ribs) in oviraptorids (Clark et al. 1999) and some dromaeosaurids (Norell and Makovicky 1999) is sometimes mentioned in this context (Paul 2001; Perry 2001). However, avian uncinate processes function primarily in strengthening the ribcage and stabilizing the shoulder musculature (Bellairs and Jenkin 1960; King and King 1979; Hildebrand and Goslow 2001); they have no particular role in sternocostal ventilation of the avian lungs. Uncinate processes are absent in screamers (Anseriformes: Anhimidae), and may be reduced in other birds (Bellairs and Jenkin 1960; Brooke and Birkhead 1991). Furthermore, cartilaginous or ossified uncinate processes are also known in crocodilians (Hoffstetter and Gasc 1969; Duncker 1978; Frey 1988), Sphenodon (Wettstein 1931–37; Hofstetter and Gasc 1969), and even several temnopspondyl anamniotes, such as Eryops (W. K. Gregory 1951). Thus, the presence of uncinate processes does not correlated with respiratory adaptations.

Similarly, the pneumatized vertebrae of sauropods and some theropods, which resemble those of extant birds, have been cited as evidence of a birdlike lung/air-sac system (Bakker 1986; Reid 1997a; Britt et al. 1998; Perry and Reuter 1999; Paul 2001; Perry 2001). Caution is advised in interpreting presumed pneumatic features in the postcranial skeleton (O'Connor 1999). However, in modern birds, pneumatization of the vertebrae and ribs is invariably accomplished by diverticuli of the cervical air sacs (McLelland 1989a), which are located outside the trunk and contribute little, if anything, to the respiratory air flow (Scheid and Piiper 1989). Presence of pneumatized vertebrae in nonavian dinosaurs therefore only speaks of the possible presence of such nonrespiratory diverticuli, and cannot be regarded as indicative of an extensive, avian-style abdominal air-sac system. Note that the presence of diverticuli of the upper airways is an apparent archosaurian synapomorphy (Witmer 1995b, 1997a), and that other sauropsids also possess nonvascularized, saclike portions of the respiratory tract (Duncker 1978; Perry 1983) without possessing parabronchial lungs.

Consequently, there is no compelling evidence that any nonavian dinosaur possessed musculoskeletal modifications to ventilate an avian-like parabronchial lung/abdominal air-sac system. It is possible that a less highly derived, protoparabronchial lung may have existed in some dinosaurs (Perry 1992, 2001), but at present, there is no unequivocal indication of the presence thereof, and such a reconstruction must be considered speculative (Perry and Reuter 1999).

Recently, several authors have presented a novel hypothesis, in which nonavian theropods may have used their well-developed gastralia (dermal ossifications of the abdominal wall) to ventilate an avian-like abdominal air-sac system (Claessens 1997; Carrier and Farmer 2000). Although gastralia, which occur primitively throughout amniotes (Romer 1956; Carrier and Farmer 2000), but which are absent in all extant birds, can hardly be considered a diagnostic correlate of a derived, avian-like lung/air-sac system, it is also not clear that these ossifications necessarily preclude the presence of such a system, and this intriguing proposal deserves further investigation. Nonetheless, there are several problems with the proposed mechanism of cuirassal breathing, in which action of the pelvic muscles is thought to depress the medial aspect of the gastralia, thereby generating negative abdominal pressures that help fill the lungs during inhalation. In extant crocodilians, as well as in Sphenodon, the gastralia are not known to contribute to the generation of either negative or positive abdominal pressure during lung ventilation (Farmer and Carrier 2000). Furthermore, in extant forms, the muscles postulated for cuirassal breathing in nonavian theropods (Mm. ischiotruncus and caudotruncus) do not insert on the medial aspects of the gastralia, but insert on the dorsolateral aspects instead (Farmer and Carrier 2000). There is, in other words, no extant example of the model proposed. Finally, in nonavian theropod dinosaurs, the gastralia are limited to the ventral body wall, and an extensive flank region exists between the gastralia and the caudal abdominal ribs. Negative abdominal pressures generated through the proposed cuirassal breathing mechanism would therefore have resulted in paradoxical inward movement of the lateral abdominal wall, resulting in unavoidable loss of ventilatory efficiency. At present, the cuirassal breathing model for theropod ventilation must be considered highly speculative, at best.

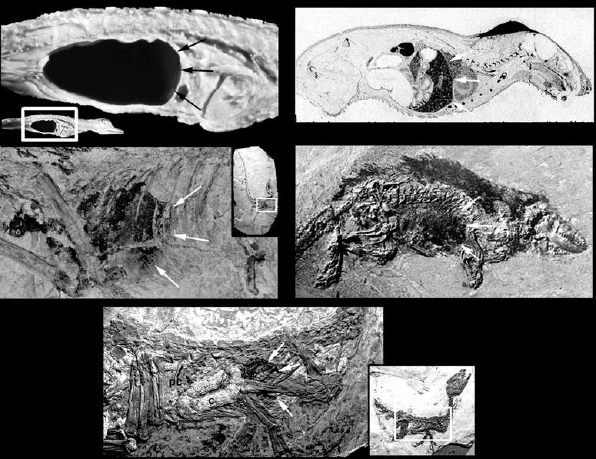

Ruben et al. (1997a, 1999) proposed a third alternative model for lung ventilation in nonavian theropods, which invokes a crocodilian-like hepatic-piston mechanism. Fossilized remains of soft tissues in two theropods, Sinosauropteryx (Chen et al. 1998) and Scipionyx (Dal Sasso and Signore 1998), suggest that the abdominal cavity of these theropods was subdivided in distinct cranial (pleuropericardial) and caudal (peritoneal) cavities (figs. 28.3, 28.4). In both cases, pigmented stains representing the remains of liver and intestinal tissues are restricted to the caudal region. In each case, the pigmentation extends from the vertebral column to the ventral thoracic wall (Ruben et al. 1997a, 1999). In Sinosauropteryx, comparatively few structural details of the abdominal viscera can be discerned, but in Scipionyx, exceptionally well-preserved structures include fine transverse folds of the intestinal wall. In Scipionyx, the liver is most readily visible under ultraviolet light, when it appears as a dark-indigo region distinct from other structures of the specimen or the surrounding matrix (fig. 28.3; Ruben et al. 1999). The color is significant, and strongly suggestive of preserved liver remains, because the fluorescence of biliverdin, a primary liver bile pigment in nonmammalian tetrapods, includes a primary emission peak in the blue region of the visible spectrum (~470 nm; Song et al. 1973). This indigo region extends vertically from the vertebral column to the ventral body wall (fig. 28.3; Ruben et al. 1999). Cranial to the liver, the pleuropericardial region is empty, because the delicate lung tissues were not fossilized, a preservational condition identical to that of exquisitely preserved Eocene mammals from Messel (fig. 28.3).

The distinct, vertically oriented division between the pigmented abdominal and the apparently empty pleuropericardial regions in both Sinosauropteryx and Scipionyx suggests the presence of a complete diaphragmatic separation between these body cavities, which is inconsistent with the extensive abdominal air-sac system associated with the avian parabronchial lungs. In extant birds, a vertical subdivision of the body cavity is absent, and the liver is located largely or entirely ventral to the parabronchial lungs, which are themselves firmly attached to the dorsal ribcage (Duncker 1978; Perry 1983; McLelland 1989a). In contrast, such a division is consistent with a mammal-like or crocodilian-like arrangement (fig. 28.3), in which a complete diaphragm separates the lungs from the liver and other abdominal viscera.

The positions of the colon and the trachea in Scipionyx also argue against the presence of a birdlike lung/air-sac system in this animal (Ruben et al. 1999). The caudal segment of the spectacularly well-preserved colon is situated far dorsally, and lies close to the lumbar and sacral vertebrae (fig. 28.3). This position is comparable with that of the colon in extant crocodilians and mammals, but is unlike that of extant birds, in which the colon is suspended in the midabdominal cavity, between and below the large abdominal air sacs, and at some distance from the vertebral column (Duncker 1978).

A portion of the trachea is preserved immediately cranial to the pectoral girdle of Scipionyx. It is located well ventral to the vertebral column, in a position comparable with that of crocodilians, in which the trachea enters the lung at its cranioventral apex, close to the sternum (Duncker 1978), but unlike that of most birds, in which the parabronchial lung is necessarily attached to the dorsal portion of the ribcage and the trachea lies close to the cervical vertebrae (Duncker 1978; McLelland 1989b).

In extant crocodilians, the vertically oriented liver and diaphragm function in conjunction with longitudinal flank muscles to produce a pistonlike mechanism for supplemental lung ventilation. The close resemblance of the liver and the abdominal subdivision in Scipionyx and Sinosauropteryx to those of extant crocodilians suggests that a similar hepatic-piston mechanism may also have been present in the theropods. Other aspects of theropod anatomy are consistent with this reconstruction (Ruben et al. 1997a; 1999). The triradiate pelvis of Scipionyx, Sinosauropteryx, and other nonavian theropods broadly resembles that of modern and basal crocodylomorphs, such as protosuchids and sphenosuchids. Specifically, in both groups, the pubis comprises a robust, rodlike ramus, often with a marked distal expansion (Romer 1956; Carrier and Farmer 2000; Jones and Ruben 2001). In crocodylomorphs, this expansion consists of a transversely oriented blade, the craniolateral edge of which, following the condition of extant crocodilians, is one of the main attachment sites for the diaphragmaticus muscles that drive the hepatic piston (Gans and Clark 1976; Ruben et al. 1997a; Carrier and Farmer 2000). In extant crocodilians, other slips of M. diaphragmaticus also attach more proximally on the pubis and caudal gastralia and on the acetabular region of the ischium (Gans and Clark 1976; Ruben et al. 1997; Farmer and Carrier 2000). In theropods, whose deeper and narrower trunks resulted in comparatively more elongate pubes with a craniocaudally oriented boot, diaphragmaticus-like musculature may have had a similar attachment. Significantly, a small patch of longitudinally oriented muscle fibers, preserved immediately cranial to the pubis of Scipionyx, dorsal to the gastralia, appears to represent a remnant of the diaphragmatic musculature of this theropod (Ruben et al. 1999). This patch fluoresces in much the same way as preserved musculature in other parts of the body (e.g., at the base of the tail and in the pectoral area; Dal Sasso and Signore 1998). No other longitudinally oriented muscle fibers would be expected in this location.

FIGURE 28.3. Similar body cavity partitioning in extant crocodilians (Alligator, top left) and mammals (Rattus, top right), and fossils of Sinosauropteryx (center left), Scipionyx (bottom, under ultraviolet illumination), and the Eocene mammal Pholidocercus (center right). Arrows delineate the vertical division between the pleuropericardial (cranial) and peritoneal (caudal) cavities. Insets show entire animal for perspective. (After Jones and Ruben 2001; center right, modified from von Koenigswald et al. 1988.)

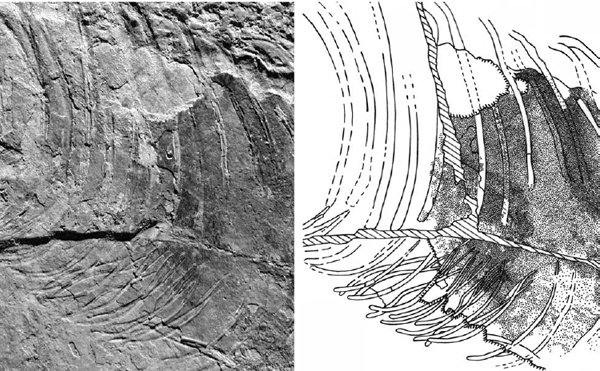

FIGURE 28.4. Close-up of the thorax of Sinosauropteryx prima. Cracks passing through this region (indicated in the drawing by hatched lines and shaded areas) do not affect most of the cranial margin of the abdominal stain. See text for details. (Digital photo by W. J. Hillenius.)

In this reconstruction of theropod ventilation, inhalation involved both conventional costal action and expansion of the ribcage, and contraction of diaphragmaticus muscles that extended between the liver and the pelvis. The latter action would have resulted in caudal displacement of the liver and a supplemental increase in pleural cavity volume. Relaxation of the flank muscles during this phase would have allowed the displaced abdominal viscera to bulge outward—similar to the condition during inhalation in extant crocodilians (Boelaert 1942; Farmer and Carrier 2000). Exhalation would have involved, in addition to conventional costal mechanisms, contraction of the flank musculature, which, possibly acting in conjunction with the gastralia, restored the abdominal viscera and liver to their original positions. Farmer and Carrier (2000) assert that in extant crocodilians, mobility of the pubis is an important component of the hepatic-piston mechanism, presumably to prevent undue intraabdominal pressure build-up from interfering with venous blood flow from the hind limbs. However, elevated intraabdominal pressures do not pose a problem during diaphragmatic breathing in extant mammals (which do not have mobile pubes, but in which liver movement can nevertheless contribute considerably to ventilation; Bramble and Jenkins 1993). Documented intraabdominal pressures in exercising humans (38 mm Hg, or approximately 5 kPa; Grillner et al. 1978) far exceed those reported for exercising alligators (~3.5 kPa; Farmer and Carrier 2000) without deleterious effects. In any case, elsewhere, Carrier and Farmer (2000) indicate that the diaphragmaticus musculature probably evolved in crocodylomorphs prior to pubic mobility. It seems likely that pubic mobility is a secondary crocodilian development, with an uncertain relationship to hepatic-piston ventilation, and there is little reason to suspect that absence of pubic mobility in theropods would preclude such a mechanism from operating in these animals.

Criticisms of the hepatic-piston model largely fall into three categories: (1) the division of the abdominal cavity seen in Sinosauropteryx is not real, but artifactual; (2) internal organs were dislocated as a consequence of postmortem compression; and (3) there is no room on the theropod pubis for diaphragmaticus musculature. Paul (2001) and Currie and Chen (2001) suggested that the division between the thoracic and abdominal cavities in Sinosauropteryx represents an artifactual result of cracks and breaks. However, although several cracks do pass through the region in question, the margin of the pigmented region is mostly unaffected by these (fig. 28.4). A dislodged chip has obliterated the uppermost margin of the abdominal stain, immediately below the vertebral column, as Currie and Chen (2001) pointed out, but the remainder of the edge of the stain is real. The colored, plaster-filled crack, to which both Paul (2001) and Currie and Chen (2001) alluded, passes more or less vertically through this region, but does not coincide with the margin of the liver stain; a continuation of the pigmentation is readily observed cranial to this crack (fig. 28.4). Finally, a cranioventral crack, which passes diagonally from the center of the ribcage caudoventrally toward the gastralia, also does not coincide with the margin of the stain: unstained matrix from the pleuropericardial cavity cranial to the diaphragm can be seen between the stained area and this crack (fig. 28.4). Although the cranial margin of the abdominal stain of Sinosauropteryx is not well defined, nevertheless, there remains a clear qualitative division between the stained caudal and unstained cranial halves of the abdominal region of Sinosauropteryx. This division extends vertically from the vertebral column to the gastralia, and is fully consistent with a diaphragmatic division of the pleuroperitoneal cavity, such as that seen in extant crocodilian archosaurs, but inconsistent with an extensive, avian-like abdominal air-sac system.

Currie and Chen (2001) furthermore doubted that soft structures in the abdominal cavity could have maintained their original shape and position as the individuals collapsed into two dimensions. However, there is no sign of trauma or violence in either Sinosauropteryx or Scipionyx. In both specimens, the skeletons are preserved fully articulated and intact, with the ribs and gastralia in their natural positions, indicating that little or no postmortem abdominal bloating took place. That soft tissues were preserved at all suggests that bacterial decomposition had not progressed very far before burial. In particular, in Scipionyx, preserved structures include exceptional detail of the wall of the large intestine, in which fine rugose foldings can be readily discerned; the preservation of the horny claw sheaths on several of the digits; and muscular tissues in several areas of the body (Dal Sasso and Signore 1998). All these indicate quick postmortem burial, or at least removal from oxic conditions conducive to bacterial proliferation (Dal Sasso and Signore 1998). Generally, the liver is a comparatively solid organ, and it is not especially surprising that it could have survived a brief postmortem period prior to burial, whereas the more delicate lungs and small intestines did not. Furthermore, in extant crocodilians, the liver is attached by ligaments to the dorsal aspect of the body cavity, and largely rotates around this attachment during ventilation (Gans and Clark 1976); a similar attachment in theropods would have anchored the liver dorsally and prevented excessive dislocation of this organ prior to burial and preservation. Both Sinosauropteryx and Scipionyx materials appear to have collapsed gently and orthogonally, probably well after burial, during the general compaction of the sedimentary beds in which they were preserved. In Sinosauropteryx, the abdominal viscera are preserved as a carbonized film (Chen et al 1998; Currie and Chen 2001), which almost certainly would have settled on the substrate before sediment compaction took place. Likewise, in Scipionyx, the liver is identified primarily by the indigo stain that corresponds to preserved remnants of liver compounds. These, too, would have settled onto the underlying sediment early in the taphonomic process, before compaction of the sediment. Given that every indication suggests these individuals settled and were buried in a low-energy environment, with minimal, if any, skeletal displacement, there is no reason to suspect the internal organs were not faithfully preserved in situ.

Martill et al. (2000) interpreted a conical, calcitic structure, associated with a partial skeleton of a small coelurosaurian theropod, as a lithified section of the colonic tract. A portion of this tract has a midabdominal position, and these authors suggest it more accurately reflects theropod anatomy than the colon in Scipionyx. However, the structure in question is oriented at a steep oblique angle to the vertebral column as it first approaches the pubic canal, then makes several turns and a sharp, ventromedial loop as it enters the canal and extends between the pubes and ischia (Martill et al. 2000). In neither extant birds nor extant crocodilians does the colonic tract possess such acute flexures, which would probably interfere with the movement of fecal matter toward the cloaca. Instead, the colon of extant forms is almost invariably a straight tract, parallel to the vertebral column, between the ileum and the cloaca (McLelland 1979; Guard 1980; Zug et al. 2001), and the same may reasonably be expected in extinct dinosaurs. The conformation of the presumed colon in this theropod fossil therefore almost certainly reflects significant postmortem displacement of these tissues.

Hutchinson (2001a) considered it unlikely that nonavian theropods had a crocodilian-like diaphragmaticus muscle, because pelvic muscles (Mm. puboischiofemoralis 1 et 2) occupied the cranial and caudal surfaces, respectively, of the pubic apron. However, the diaphragmaticus muscle does not attach to the pubic apron in extant crocodilians, inserting instead on the craniolateral edge of the distal part of the pubis, between and ventral to the sites of attachment of Mm. puboischiofemoralis 1 et 2 (other slips of M. diaphragmaticus insert on more proximal section of the pubis, and the acetabular region of the ischium; Gans and Clark 1976; Ruben et al. 1997a; Carrier and Farmer 2000). Elsewhere, Hutchinson (2001a) suggested that the lateral surface of the distal pubis and the pubic boot of theropods served mainly for abdominal muscles, including M. rectus abdominis. The crocodilian diaphragmaticus muscles are considered to be derivatives of at least the caudal portion of M. rectus abdominis (Carrier and Farmer 2000). Therefore, there is no conflict between Hutchinson's (2001a) reconstruction of theropod pelvic musculature and the presence of a diaphragmaticus-like muscular system in these animals.

If a diaphragmaticus-like muscle did attach to the pubis, retroversion of the pubis, such as that found in Herrerasaurus and some maniraptoran theropods (Hutchinson 2001a) would effectively have resulted in elongation of this muscle. This may have permitted additional travel of the liver during hepatic-piston ventilation, and an additional expansion of lung tidal volume in these animals.

Significance for Dinosaur Physiology

Whereas respiratory turbinates may provide significant insight into the minimal levels of chronic resting ventilation and metabolic rate (and the likely absence of these structures in dinosaurs therefore suggests that these animals probably lacked mammal-or birdlike resting rates, and instead were likely ectothermic), lung structure is more informative with regard to the maximum sustainable ventilatory capacity (i.e., that used during strenuous sustainable exercise). Unfortunately, as no fossilized lung tissues have yet been documented, reconstructions of dinosaurian lungs must therefore rely on indirect evidence. A mammal-like alveolar lung is precluded on phylogenetic grounds: it is associated only with the synapsid clade. There is no unambiguous evidence to support a level II inference that any nonavian dinosaur possessed a highly derived, birdlike parabronchial lung with an extensive abdominal air-sac system; nonavian dinosaurs lack the musculoskeletal adaptations associated with the ventilation of this kind of lung in all modern birds, including flightless forms. Without such lungs, it is unreasonable to infer the high levels of sustained maximal aerobic activity characteristic of extant birds. The available evidence does, however, permit the inference of an unmodified septate lung, such as that probably present primitively in archosaurs, and in extant crocodilians: a heterogenous, multicameral lung with conventional tidal ventilation. Although some prerequisite attributes of an avian-like parabronchial lung are present in crocodilian lungs (i.e., heterogeneous chambers, tubular dorsal chambers, and communicating pores between adjacent chambers; Perry 1992), and it is therefore theoretically conceivable that some nonavian dinosaurs had modified these attributes into a protoparabronchial lung, there is no evidence to indicate that any had, in fact, done so, and this reconstruction of a more derived kind of lung must be considered entirely conjectural. An unmodified septate lung is consistent with an overall ectothermic physiology and a comparatively limited metabolic scope for the majority of dinosaurs. However, the presence of a hepatic-piston mechanism to augment costal lung ventilation in nonavian theropods may indicate that the aerobic capacity of this group was expanded beyond that known for extant reptilian ectotherms, because it suggests the kind of ventilatory changes Hicks and Farmer (1998, 1999) alluded to for increasing the capacity for gas exchange of septate lungs. Even with a resting physiology of ectotherms, nonavian theropods may have been capable of sustaining levels of activity above that of any modern reptile. Theropods may thus have had the best of both worlds: low, reptilian-grade maintenance costs during equable climatic conditions, but with an enhanced capacity for aerobic activity, perhaps partly overlapping that of some mammals (although the limits of theropod activity capacity are currently not quantifiable; Hicks and Farmer 1998, 1999; Ruben et al. 1998b). Such a potential combination of metabolic traits is not otherwise known among tetrapods.

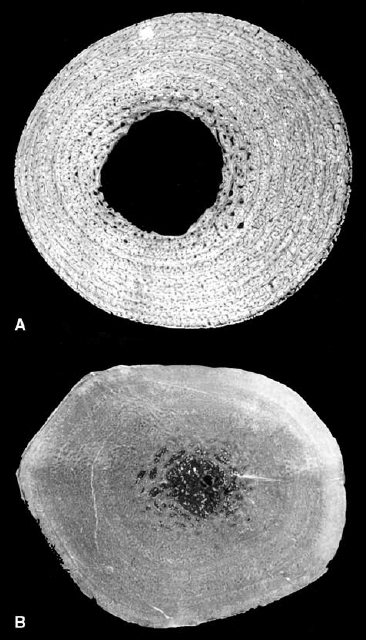

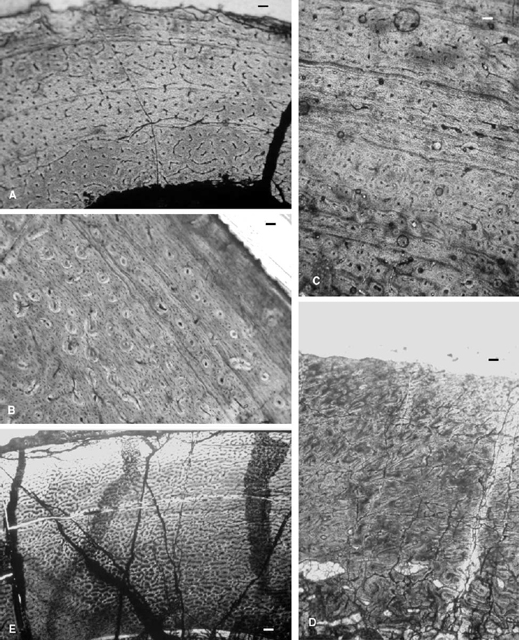

Bone Microstructure and Thermoregulation

Over the past several decades, bone microstructure has been used to deduce various aspects of the physiology of dinosaurs (Ricqlès 1980, 1983; Reid 1984a, 1984b; Bakker 1986). However, it is increasingly recognized that there is no direct connection between bone microstructure, physiology, and metabolic rates (Chinsamy 1994, 2000). Ever since Amprino (1947), different bone depositional rates were thought to result in distinctly different kinds of bone microstructure. Recent research by Starck and Chinsamy (2002), however, documents that a single kind of bone tissue can result from a range of bone depositional rates, and emphasizes that the relationship between bone depositional rate and bone tissue is therefore not as clear-cut as previously assumed. Although qualitatively, Amprino's rule still holds true, caution is advised in making quantitative deductions regarding rates of bone tissue formation across taxa. Extrapolating physiological parameters from bone microstructure is highly problematic, because bone microstructure is riddled with mixed messages, as discussed below.

Zonal versus Azonal Bone

Seasonal changes in ambient conditions can result in alternating periods of fast and slow growth in extant reptiles (Hutton 1986), and this pattern is reflected in the bone microstructure of the animal: cycles of bone depicting alternating fast and slow rates of deposition are visible in the compacta of bones of turtles, lizards, and crocodilians (Castanet et al. 1993). The resulting bone tissue is referred to as “zonal bone.” Other extant ectotherms, such as frogs and fishes, also grow in a cyclical manner. In contrast, mammals and birds generally grow in a rapid manner, unhindered by environmental or climatic disruptions (Chinsamy and Dodson 1995). This rapid, sustained rate of growth is also reflected in the bone microstructure: avian and mammalian bone is usually deposited in an uninterrupted, azonal manner. The rate of bone formation in endotherms is related to ontogeny, and generally does not undergo cyclical changes. For example, the initial rapid rate of juvenile growth in mammals and birds results in fibrolamellar bone, whereas more mature animals, with much slower rates of growth and bone formation, form parallel-fibered or lamellated bone (Chinsamy 1995a; Chinsamy and Dodson 1995). Rest lines are commonly found only in the peripheral regions of mature mammals and birds, and are indicative of a determinate growth strategy. Some notable exceptions to this general pattern exist in endotherms: under certain circumstances, growth rings form in mammalian bone. This happens particularly among marine mammals (porpoises; Buffrénil 1982), mammals from strongly seasonal, cold climatic zones (polar bears; Chinsamy and Dodson 1995; Chinsamy 1997), and several small hibernators (Klevezal and Kleinenberg 1969) that periodically either shut down or redirect energy allocations. In addition, Castanet et al. (1993) suggest that lines of arrested growth (LAGs) could form as a result of illness, starvation or disease, but this relationship is not well understood, and recent studies on extant birds that have suffered trauma (Tumarkin and Chinsamy 2001; Starck and Chinsamy 2002) do not support this purported link. Among modern birds, rest lines are reported in the slowly formed, outer, circumferentially lamellated bone (i.e., formed after the mature body size is reached); this situation is different from the LAGs and annuli that interrupt fibrolamellar bone in growing bones of several nonavian dinosaurs and nonornithurine birds (Chinsamy 2000). (In this context, note the so-called “Harris lines,” which are recognized in X-rays in the epiphyseal regions of long bones of children that have endured severe illness. Harris lines are distinctly different from LAGs, which occur in the cortical bone of the diaphysis of long bones, and not in the epiphyseal region. Interestingly, Harris lines were not observed in the bones of young elephants that succumbed to drought [Chinsamy, unpublished]). Thus, although the circumstances under which LAGs form in the cortical bone of mammals and birds remain unclear, they are isolated occurrences. This contrasts with the LAGs and annuli of extant ectotherms and several dinosaur taxa, which appear regularly throughout ontogeny.