TWENTY-NINE

Dinosaur Physiology

When Richard Owen named Dinosauria (1842b), he did so specifically to set them apart from other reptiles. He had only a few forms to work with, and they were known only from fragmentary remains. However, even on the basis of what was then known about Iguanodon, Hylaeosaurus, and Megalosaurus, Owen knew two things about these animals: that they belonged together, and that they were like no other reptiles ever discovered, living or extinct (Torrens 1992).

Today, when we look at the paintings and statues of these early dinosaurs made by such artists as Waterhouse Hawkins under Owen's direction (fig. 29.1), we might regard them as quaint and crude, because we know so much more about the anatomy of dinosaurs now. But if we look closely, we can tell these are representations of dinosaurs, not of other reptiles, and not just because they are so large. These are dinosaurs because they have an erect posture, which no one would have dreamed of giving a reptile. This stance is one of the main reasons why Owen knew dinosaurs were different from other reptiles. He knew they had to stand erect; they could not sprawl like other reptiles. In fact, it was why he concluded that of all reptiles, dinosaurs most closely approached the mammalian condition (Desmond 1979).

However, Owen stopped short of concluding that dinosaurs were as physiologically advanced as mammals, and he had a precise philosophical reason (Desmond 1982). Owen was committed to an implicit principle of nineteenth-century biology—that of typology, or the assumption that all animals that were classified in a single group automatically shared the same general features of structure and physiology (Russell 1916). This view does not allow transitions among major and different groups of organisms. Dinosaurs could not be as metabolically “advanced” as mammals, because their skeletal features clearly showed that they were reptiles, and reptiles are not warm blooded (Desmond 1979). In 1870, Owen drew the same conclusions about pterosaurs. These flying reptiles were so similar to birds in many skeletal respects that other paleontologists, such as H.G. Seeley, suggested that they were warm blooded. But Owen refused this conclusion—again, because pterosaurs were not birds, but reptiles (Padian 1995a).

To Owen, all the structural sophistication of dinosaurs and pterosaurs that approached the conditions of mammals and birds were in his words “purely adaptive,” and not indications of advanced metabolism. As far as the Victorians knew, dinosaurs and pterosaurs had no insulatory covering, such as feathers or fur, and so could not be endothermic. “We say that Archaeopteryx was warm-blooded because it had feathers, not because it could fly,” Owen said (1870:73), and it was feathers that made it a bird, even though it retained a long reptilian tail and teeth (Desmond 1982). Like any taxonomist, Owen picked out key characters, such as feathers, and ignored others, to establish taxonomic position. Once they were classified, Owen could automatically infer all the physiological features of the extinct members of the group from the living ones. Although Archaeopteryx was utterly unlike any living bird, and no one knew how well it could fly or what its internal temperature was, it had feathers and therefore to Owen was a bird, as different from reptiles as it was from any fish.

Typology has long ceased to be a guiding principle of evolutionary biology; in fact, Ernst Mayr devoted a large part of his long career to destroying its credibility (e.g., Mayr 1942, 1963, 1982). However, Mayr was talking about a “typology” of species and populations, in which the variation necessary as the raw material of evolution was not recognized. This was not the sense of typology that Owen recognized, nor that we discuss here. Owen accepted evolution but not transmutation by material forces, such as natural selection (Desmond 1982); his acceptance of a vertebrate “Archetype,” for example, was an Aristotelian concept (Rupke 1994), a Bauplan on which actual animals could be built (Padian 1997a).

Typological thinking is useful in many respects; it is merely a generalization based on experience, from a smaller set of individuals to a larger class of them. We use typological thinking all the time; for example, when we presume that the relatives of a given bug that has been killed by a new pesticide will also fall to it, when we describe a “veliger” or “nauplius” larval stage through which diverse groups of invertebrates pass, or when we avoid any aposematically colored snake, because it might be poisonous. Typology is useful in these respects, but it is inimical to evolutionary thinking, because it emphasizes the “typical” and even (in a pre-evolutionary sense) “fixed” characters of a taxon. Therefore it ignores the diversity on which evolutionary change is built. It minimizes the importance of variation; it is antithetical to “populational thinking” (Mayr 1963), and it ignores possibly intermediate and transitional features and forms. When Darwin and Wallace (1859) supplied the mechanism of natural selection to explain the transmutation of species, it became intellectually respectable to accept that evolution had actually occurred, and therefore, that all organisms could plausibly have descended from other organisms (Ellegård 1958). (Darwin's only figure in The Origin of Species is devoted to this concept.) If all this evolution had indeed happened, then the boundaries that separate traditional Linnean classes, orders, families, and so on must be to some degree arbitrary. For Darwin, typology was not only an obstacle to sensible classification, but to the understanding of evolution itself, as his letters to Water-house and Huxley make clear (Padian 1999). This was a different view than Owen's, even though contemporary with it.

FIGURE 29.1. Detail of a painting by Waterhouse Hawkins of the exhibits for the Crystal Palace, outside London, 1858. (Courtesy of E.H. Colbert.)

The irony of Owen's construction of Dinosauria as a group so different from other reptiles will not be lost on most readers today. Owen was relentlessly typological (Desmond 1979; Rupke 1994; Padian 1995c, 1997a). In fact, he singlehandedly resuscitated the concept of the archetype from the ashes of Geoffroy's devastation at Cuvier's hands two decades before (Appel 1987), even though at first, he was violently opposed to the concept (Sloan 1992; Padian 1995c, 1997a). He accepted a kind of transmutation of species, but not completely by natural means, and he would not have accepted that birds evolved from any known kind of reptile, living or extinct (Desmond 1982). Yet he had no hesitation in proclaiming dinosaurs different from other reptiles and as close to the mammalian condition as reptiles had ever come.

It is all the more ironic, then, that today, there is such interest in defending dinosaurs as mere reptiles. These authors do not use phylogenetic analysis that underlies the comparative method we outline below, and that Witmer (1995a) epitomized so well in his concept of the Extant Phylogenetic Bracket (EPB). We agree that, without a phylogenetic perspective, it is difficult to see how to evolve from one set of taxa with certain characters and features (e.g., basal reptiles) to another (e.g., dinosaurs and eventually birds). If we do not study these problems phylogenetically, even if we admit that there is some “variation” within groups, how are we escaping typology?

We contend that, with a few exceptions, the continuing dialectic about dinosaur physiology is less a matter of evidence than of preconception (Padian and Horner 2002). Those workers who are impressed that dinosaurs are reptiles are inclined to begin with the assumption that dinosaurs were ectothermic because they were reptiles; that in their features of structure, growth, and behavior, they were much like living reptiles; and that no particular evidence need be adduced to support this default position. This position, we contend, is typological and is even argued in the terms that Owen, Linnaeus, and other pre-Darwinians used.

However, those workers who conclude that dinosaurs were more like birds and mammals than like other living reptiles find many analogical features that extinct dinosaurs share with mammals and birds. They also use the EPB approach, and are impressed by the many phylogenetic analyses that conclude that birds evolved from dinosaurs and that dinosaurs share many unique features with birds. This argument is thus based on both structural analogy and phylogeny, specifically phylogenetic systematics; but whether this heritage is enough to draw physiological inferences depends on the extent to which those shared features of birds and other dinosaurs have distinct physiological implications (Witmer 1995a).

Because nonavialan dinosaurs are extinct, it is not possible to decide conclusively most aspects of their physiology and behavior. On the basis of the evidence that we discuss below, we contend that (1) dinosaurs were, in many respects, more like living large birds and mammals than they were like living reptiles; (2) more physiological advances occurred at or near the origin of dinosaurs than at the origin of birds; (3) not all dinosaurs were alike in these physiological respects, any more than living mammals or birds are all alike; and (4) comparative biology is a better guide to evolutionary paleobiology than typology is. We also discuss some suggestions for the possible resolution of problems based more on definition and preconception than on evidence.

Methods

We accept that phylogenetic reconstruction based on shared derived characters is the most reliable guide to understanding the actual pattern of evolution. This is the view of the great majority of systematic biologists, regardless of what taxon they work on, and whether they analyze molecules or fossils. And, as many works have shown (Eldredge and Cracraft 1980; Padian 1982, 1995b, 2001a; Brooks and McLennan 1991), phylogeny is a useful test of hypotheses about evolutionary processes as played out in evolving lineages.

Hypotheses about whether a particular extinct organism had a certain physiological or behavioral condition or feature can be assessed in only two ways. First, it must be shown that a certain structure (or other evidence preservable in fossils) was necessary and sufficient for the condition in question. Second, the same structure must be unambiguously necessary and sufficient in a living animal (the actualistic hypothesis). So far, no unambiguous indicators of physiology are recognized in the fossil record. All indicators are indirect, correlated to a greater or lesser extent with metabolism. But no feature, despite some published statements, is “causally correlated” or a “Rosetta Stone” for metabolism. Consequently, the presence or absence of a single feature connected to physiology is less persuasive than a pattern of several such features placed in phylogenetic context.

Hypotheses about how a given condition evolved in a line-age are hypotheses of process. Normally, they are guided and constrained by what we think we know about the biology of living organisms. We sometimes allow that evolution may have pushed some extinct forms to different limits when they fall outside the range of extant organisms. We can construct any number of hypotheses about how a given condition evolved, but how do we know which of these hypotheses is more plausible than any other? One way is to examine the pattern of evolution of the lineage in question, based on robust phylogenies. Phylogenetic patterns, based on cladistic methods, do not rely on ideas about what evolutionary processes and pathways are more or less likely. So they provide an independent test of process-based hypotheses, without being final arbiters (Eldredge and Cracraft 1980; Padian 1982, 1995b, 2001a).

For example, a perspective unrooted in phylogeny could regard dinosaurs as ectothermic simply because they are reptiles and not birds or mammals. An alternate approach would map characters related to physiology and behavior on a phylogeny built from other characters, and infer from this logical structure the points at which the former characters may have first appeared (Eldredge and Cracraft 1980; Brooks and McLennan 1991; Witmer 1995a). To be considered seriously in this debate, any feature must be uniquely shared and must have uniquely demonstrable metabolic consequences. This is why it is not enough merely to look at single features; the entire picture must be considered.

Typological Approaches to Dinosaurian Biology

All authors who review the history of issues of physiology, metabolism, and behavior in extinct dinosaurs agree that these questions will never reach unanimity, because direct observation is impossible. In published works, the statements that follow this truism generally explain the authors' respective philosophical bases. We review some recent syntheses of the issues, because the philosophical structure of these arguments is at least as important as the adduced evidence.

Paladino et al. (1997) provided a thoughtful and readable perspective that dinosaurs were essentially little more than gigantic versions of large living reptiles, such as sea turtles and Komodo dragons (see also Paladino and Spotila 1994). Their approach is to look at metabolic processes in living reptiles and to extrapolate how they would work at the larger sizes of dinosaurs. This is a perfectly defensible approach, of course; it is one way to predict what dinosaurs might actually have done. But how would we know if the projections were inaccurate?

To begin with, Paladino et al. (1997) suggest that paleontologists may have relied too much on a phylogenetic approach when considering paleophysiology. Because extinct dinosaurs are more closely related to birds than to crocodiles, paleontologists may be predisposed to conclude that birds are better metabolic models than are crocodiles. This would be a mistake, they caution, because the early members of clades are likely to be more similar to each other than to highly derived members. (We agree that this would be true, of course, providing there is clear evidence that these similarities are rooted in particular metabolic characteristics and not simply assumed.) Note that these authors are rejecting from the outset the view that phylogenetic analysis, which adduces the actual sequence of transitions of features from taxon to taxon, is a relevant method.

As an example of the pitfalls of the phylogenetic method, Paladino et al. use the classic cladistic formulation that the lung-fish is phylogenetically closer to the cow than to the trout. This is a mistake for interpreting physiology, they say, because the trout and lungfish have more primitive characters in common, and this vindicates the traditional Linnean system that regards these two animals as fishes. But for several reasons, this is a poor example. First, one hardly needs a cladogram to demonstrate that cows are far different physiologically from the other two animals. Second, lungfishes actually share some features with all tetrapods (not only the admittedly extreme example of cows) that are physiologically important. They have internal choanae, functional lungs, fleshy limbs, and the ability to survive seasonal dryness. We do not know if the first tetrapods were physiologically more like the lungfishes of today than like tetrapods of today, but they could certainly do things that both ancient and living trout relatives cannot. And these features were directly related to the ability of such sarcopterygians to survive on land. This is why we need to use phylogeny, not discount it.

Paladino et al. (1997:492) note that living birds do not have teeth or a long bony tail, although “some Mesozoic birds did,” and that these are “two other features in which dinosaurs more closely resemble crocodilians than modern birds.” Hence, we should conclude that dinosaurs were more like crocodiles than birds. But if basal birds had teeth and a long bony tail, why were they not like crocodiles too, even though they had feathers (as we now know the closest dinosaurs to birds did)? This inconsistency in logic underscores the problem of abandoning a phylogenetic perspective in asking evolutionary questions.

Despite these limitations, Paladino et al. (1997) summarize a great deal of comparative information about the physiology of living animals and extrapolate situations for extinct dinosaurs, based on first principles and data from extant forms. They conclude that dinosaurs could have functioned perfectly well as gigantic versions of ectothermic reptiles. This conclusion may be valid, although we will argue below that other data suggest an interpretation that is more consistent with empirical observations.

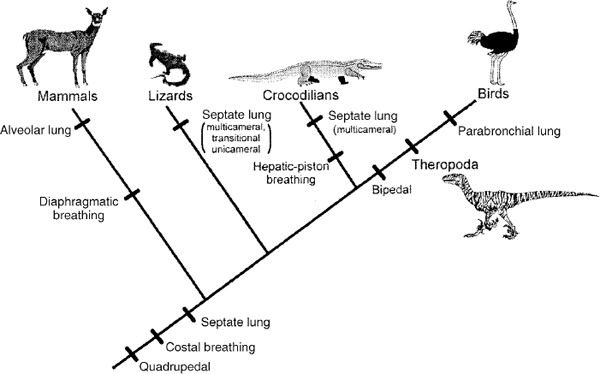

FIGURE 29.2. Phylogenetic distribution of amniote lungs. (From Hicks and Farmer 1999.)

Ruben and his colleagues (e.g., Ruben et al. 1997a, 1998b, 1999) rely on several key features or “Rosetta Stones” that they invoke to put to rest the idea that dinosaurs had any avian or mammalian physiological features. One such feature is nasal turbinates, which they say have a functional association with high lung ventilation rates and endothermy in living birds and mammals. It is not true, however, that all living birds and mammals have these structures, it has never been shown that they are essential to endothermy, and it has not been shown that dinosaurs did not have them or could not have had them (or something like them). Respiratory turbinates do not fuel lung ventilation rates, tidal volumes, or gas exchange efficiency in the lungs. They mainly recover exhalant moisture, but there are other ways that animals can conserve, store, and recover water. Moreover, such structures do not have to be ossified, and they do not have to be readily preserved in the fossil record. In Victorian times, it was acceptable, if logically weak, to argue on the basis of negative evidence (Padian 1995a, 1995b), but today it is not. Finally, Owerkowicz and Crompton (2001) have shown that both turbinates and trachea serve the functions discussed above; however, mammals use turbinates more extensively, whereas birds rely more on the trachea. In this context, it may not be surprising that Mesozoic theropods have so far shown little evidence of turbinates; however, they do have unusually long necks (Gauthier 1986).

Ruben et al. (1997a, 1998b, 1999) have also argued that dinosaurs must have had a simple unicameral lung inflated by a hepatic piston attached to the apron of the pubis, as in crocodiles. There are many problems with this interpretation (Perry 1992, 1998; Hicks and Farmer 1999; Christiansen and Bonde 2000). First, other paleontologists do not accept their interpretation that the colored stain within the body area of the small theropod dinosaur Scipionyx is the liver (Currie and Chen 2001). Second, there is no evidence that the pubic apron anchored a diaphragmaticus muscle; phylogenetic and anatomic evidence, placed in a phylogenetic framework, indicate that this area was the attachment point for M. pubo-ischio-femoralis externus 1 (Hutchinson 2001a). If a kind of M. diaphragmaticus attached here, it could only have attached superficially, but there is no evidence of it in other theropods, other dinosaurs, or any ornithosuchian outgroups. Third, the configuration of the pubic apron in theropods, as in other saurischian dinosaurs, is a variably broad plate that presents a craniodorsally oriented surface to the chest cavity. In crocodiles, the pubic apron conforms to the shape of the abdominal wall and so is an extension of the cylindrical pelvic girdle of other reptiles. Its broadest surface is ventral, approaching the ventral ribs. Thus, the structures in the two animals are oriented in completely different directions, which provides no support for functional inferences of similarity. Fourth, it is strange to posit a unicameral lung for dinosaurs. As Perry (1992, 1998) showed, a multicameral lung is far more likely, because it is so broadly distributed in reptiles; unicameral lungs are found only in small animals or those with low metabolic rates, and are clearly secondarily derived, not primitive, within reptiles (fig. 29.2). This is another reason why the phylogenetic distribution of structures must be respected in framing evolutionary hypotheses. Finally, Ruben et al. (1997a, 1998b, 1999) stated that it would not be possible to evolve an avian lung from their reconstruction of a dinosaurian lung without rupturing the internal musculature. If this statement is true, then either their reconstruction is wrong or birds could not have evolved, because Ruben et al. do not provide a model of a lung from which the avian lung could have evolved, and do not show which known animals have or could have had it ancestrally.

A Transformational Approach to Dinosaurian Physiology

Transformational approaches use hypotheses of both patterns and processes to reconstruct evolution. Reid (e.g., 1997a, 1997b) has most effectively articulated the case for “intermediate” dinosaurs in transformational terms; that is, Mesozoic dinosaurs were neither exactly like extant ectotherms nor extant endotherms, a proposition that Ostrom (1970b) first advanced and Dodson (1974) vigorously defended. In so doing, Reid has recurred to the biology of the basal archosaurs from which dinosaurs evolved, and has acknowledged the origin of birds from coelurosaurian dinosaurs in reconstructing the biological context of the first birds. The question, as Reid and other authors have pointed out, is to determine in what respects dinosaurs may have been like the ectotherms and endotherms that we know, and how they may have been different from anything known today—given that all relevant variables can only be indirectly assessed. Reid, considering the situation in living archosaurs (birds and crocodiles; Witmer 1995a), argues that dinosaurs had a circulatory system that was more like those of birds than of other reptiles, with a fully developed double-pump system and well-separated left and right chambers. Otherwise, it is difficult to imagine how large sauropod dinosaurs could have acquired their great size, and difficult to explain the long necks and cervical postures of dinosaurs in general.

Acknowledging that large dinosaurs would have been by default inertial homeotherms, immune to daily vicissitudes of temperature, Reid then asks what model is most appropriate for small dinosaurs. He noted (Reid 1997b:457) that “small forms would automatically have higher mass-specific SMRs [standard or basal metabolic rates] than large ones, without this implying any movement toward endothermy—although, lacking the temperature stabilization of mass effects, they could have been under greater selection pressure to move toward it.” Reid explains that if the model of Regal and Gans (1980) is followed, dinosaurs could have retained a low SMR that would have allowed them to devote more energy derived from their food to growth. But Reid thinks that such dinosaurs were at least moving toward endothermy, because they would have had “a double-pump circulation, full aerobic activity, and a capacity for fast continuous growth.” As Reid (1997b:468) notes, animals with this combination of characters (double-pump hearts, fast-growing fibrolamellar bone, and a cardiovascular system capable of supporting its growth) could in no way be merely large “good reptiles.” “Mass homoiothermy,” Reid continues, “also cannot explain fast continuous growth in small species and juveniles too small to show mass effects, or alone explain the ability to grow quickly to large sizes.” We agree.

Where we tend to part company with Reid is on the emphasis accorded to the interpretation of vascular structures in dinosaur bones. Reid (1997b:469) acknowledges that basal metabolic rates must be separated from various measures of activity rates, and that for the latter, there may be little difference between endotherms and ectotherms. He also acknowledges that dinosaurs grew continuously at high rates, as the predominance of well-vascularized cortical tissue in their long bones indicates. But he does not infer that this well-vascularized cortical tissue had to be produced by high basal metabolism (regardless of adult size), and for two reasons. First, other reptiles of today can produce the same tissue, sometimes in a sustained mode; and second, dinosaur bones also have other structures such as growth lines that indicate slow growth. He finds that dinosaurs would best fit an “intermediate” model between living reptiles and birds.

Certainly, living reptiles can produce bone that reflects rapid rates of growth; however, this occurs nearly always at young stages, at which stages almost all tetrapods grow more rapidly than when they are older (J. R. Horner et al. 2001). A rapidly growing young alligator, even kept at optimal conditions, does not ordinarily produce fibrolamellar bone; moreover, its vascularization, although higher than in crocodiles, is not as high as in dinosaurs, and is normally dominated by longitudinal vascular canals that are characteristic of slow-growing bone (Castanet et al. 1996). (For definitions and descriptions of these tissues, see Reid [1996, 1997a] and Ricqlès [1980].) Reid's (1997a: fig. 32.7a, b) figures of a young, wild-caught alligator from North Carolina show a matrix of bone described as fibrolamellar, with numerous small, longitudinally oriented osteons that frequently anastomose radially. For a crocodile, this is well-vascularized tissue that is probably growing rapidly; but it differs from the bones of young dinosaurs of the same size. Those dinosaur bones have larger osteons set in a laminar or plexiform pattern that reflects much higher rates of growth; there are more and larger vascular canals, and their orientations are more complex (Castanet et al. 1996; J. R. Horner et al. 2001). Furthermore, the difference between the characteristic cortical matrices of dinosaurs and pterosaurs, on the one hand, and pseudosuchians (archosaurs including and closer to crocodiles than to birds) on the other, is distinct in terms of ontogeny and phylogeny and was probably so since the split between these two archosaurian subgroups, sometime before the Late Triassic (Ricqlès et al. 2000; Padian et al. 2001b). It would be good to have more specific information about the individual alligator that Reid describes, because it appears to be anomalous with respect to the usual crocodylian (and pseudosuchian) pattern, unless it merely represents a rapidly growing juvenile stage.

Reid's (1997b:463, fig. 32.7c) other example of a rapidly growing extant reptile is bone from a half-grown Galapagos tortoise, which is well-vascularized, reticular fibrolamellar bone without growth rings. Again, we would hypothesize that the tortoise is laying down this kind of bone because it is growing rapidly, as Reid (1997b:464) also accepts; and this would be expected, because animals of large adult size generally have higher growth rates than smaller animals (Case 1978a). What is interesting, of course, is that both the alligator and the tortoise have much lower basal metabolic rates than do endotherms. If they produce the same bone as dinosaurs did through life, why claim that dinosaurs had high basal metabolic rates? In our view, the kind of bone deposited is crucial to consider: not simply whether it is reasonably well vascularized or contains fibrolamellar tissue, but how well vascularized it is, what the vascular pattern is (laminar or plexiform versus longitudinal with occasional anastomoses), and how predominant the fibrolamellar tissue is. In these respects, our observations clearly separate dinosaurs and their relatives from crocodiles and theirs (Padian et al. 2001b; Ricqlès et al. 2003).

The second point that Reid raises concerns the meaning of “growth lines” in cortical bone. These are plesiomorphic in vertebrates, and retained in mammals and birds that grow large enough, or slowly enough, to record them (J.R. Horner et al. 1999, 2000, 2001). Reid (1997b:464) takes the presence of these lines, which are found in nearly all dinosaurs, to mean that dinosaurs were “able to grow in the manner of ectothermic reptiles as well as that of endothermic mammals, and as sometimes also growing in both styles in different parts of their bodies.” This important point underscores the fact that different bones grow in different ways and at different rates in the same individual, which was as true of Mesozoic dinosaurs (Horner et al. 1999, 2000) as it is of living birds (Castanet et al. 1996).

However, not all growth lines are the same, nor do they necessarily carry the same biological meaning. In many (but not all) living taxa, they are deposited annually, and this hypothesis has been tested and sustained for at least some dinosaurs, based on independent measures of tissue growth (Horner et al. 2000). However, different numbers of lines of arrested growth (LAGs) can be deposited in different bones of the same skeleton, sometimes more lines than the plausible age of the animal (Horner et al. 1999). And although some dinosaur bones show growth lines with successively decreasing intervals toward the periphery (Reid 1997a: fig. 32.10), in others the lines can be of uneven intervals (e.g., Chinsamy 1993).

Moreover, there are many different kinds of structures called “growth lines.” Some are broad bands of avascular or nearly avascular bone that interrupt vascularized parallel-fibered or fibrolamellar bone. This is the “lamellar-zonal” structure seen in slowly growing living reptiles and amphibians. These bands represent a considerable amount of time of deposition, as their poorly vascularized structure indicates. Other lines do not comprise a separate band of deposited tissue, but are simply dark, slightly scalloped lines that may reflect not just a pause in deposition, but some erosion of previously existing tissue. These are the LAGs most commonly seen in dinosaur and pterosaur bone (Reid 1996; Horner et al. 1999, 2000; Ricqlès et al. 2000), as well as in the bones of many crocodiles and even birds and mammals (particularly those of larger size that take more than a year to mature). Other kinds of growth lines may form because of cortical drift, reproductive stress, environmental stress, seasonal variation, or endogenous rhythms. They do not always encircle the cortex completely, and they may be visible in only part of the shaft. And still others, called “false LAGs,” have no erosional structure and disappear under close magnification (Ricqlès 1980). They may represent a slight pause in deposition, but the necessary relation of these lines, like the other categories, to thermal physiology is not clear and does not appear to be the same in all taxa. For all these reasons, it is important to keep separate the different kinds of growth lines, which require more research and understanding.

Because growth lines are plesiomorphic for vertebrates, and some kinds of them are found in endotherms, it is difficult to use the simple presence of any kind of growth lines as an indication that extinct taxa were not endothermic (Horner et al. 1999, 2000; Schweitzer and Marshall 2001). We find a lot of plausibility in Reid's “intermediate” hypothesis, because it explains many patterns and presents a model that is consistent with a great deal of evidence. However, we tend to see the glass more as half full than as half empty. Our reservations are, first, that the bone matrix in dinosaurs and pterosaurs is predominantly fibrolamellar bone that is unlike those of other reptiles and reflects sustained rapid growth; and second, that “growth lines” are heterogeneous affairs that take many forms, some of which are found in living endothermic tetrapods, as well as in dinosaurs and pterosaurs.

We return to Reid's central issue, that of basal metabolic rates, which are impossible to measure directly in these extinct animals. There is no reason to assert a priori that dinosaurs were more like other reptiles in this respect than like birds and mammals. Unlike other reptiles, dinosaurs show derived features of their bone histology that are associated with sustained rapid growth and high metabolic rates in both birds and mammals. At some point, the physiological transition to the condition of living birds occurred. Basal birds may not have been exactly like living birds in all metabolic respects, but they appear to have been endothermic (pace Ruben 1991) because they have a full complement of feathers, which are ipso facto insulatory devices. They were not substantially different from other dinosaurs and pterosaurs in the osteological features that reflect growth rates and underlying sustained metabolism, even though they are different from pseudosuchian archosaurs in these respects (Padian et al. 2001b).

Finally, Chinsamy and Hillenius (this vol.) argue that because ectothermy is a primitive condition for amniotes, it is a priori parsimonious to infer that extinct amniotes, such as dinosaurs, were ectothermic, and hence it is not necessary to search for supporting evidence of this. In addition to being a misuse of the concept of parsimony (Johnson 1982), the statement is illogical. The reason is again based in our acceptance as biologists that evolution is the central principle of biology, and hence that phylogeny is a reflection of evolution. At some point, the differences that separate living descendants of lineages must have evolved. Because well more than 99.99% of all taxa that have ever lived are extinct, those transitions are likely to have occurred in fossil organisms.

If all amniotes were ectothermic, then it would be highly probable that dinosaurs were ectothermic. However, because birds are endothermic, and they evolved from reptiles, at some point, endothermic features had to evolve; and if the first birds were endothermic, this must have taken place in nonavialan theropods or in a broader ancestral group. For this reason alone, all extinct animals that lie between (endothermic) crown group birds and their next extant outgroup (ectothermic crocodiles) are of questionable physiological status that cannot be assumed a priori. A simple example will demonstrate this. Birds have fully erect posture, but crocodiles, lizards, and turtles do not. If dinosaurs were ectothermic, we would then have to assume that they were not fully erect, and we would not be required to adduce evidence to demonstrate it. However, as Owen showed when he erected the taxon, dinosaurs were indeed fully erect in a way that no other reptiles are. Witmer (1995a) formalized this principle of analysis as part of his consideration of the logic surrounding the EPB. We assume that the extinct horse Merychippus had fur not only because all horses today do, but because other perissodactyls and nearly all other mammals do, except if it is secondarily lost. But we cannot infer that a kannemeyerid dicynodont, a Triassic relative of mammals, similarly had fur, because it is outside the group of extant taxa known to have fur. The level of inference depends partly on the preservation of necessary structures that delimit the feature, and partly on the level of phylogenetic relationship.

Some dinosaurs produce LAGs and some do not. We suggest that these animals produce LAGs not because they cannot grow all year, but simply because they do not grow all year—at least, not at uniform rates. But this is also true for mammals, especially mid-sized and larger ones that take more than several weeks to mature. Food and water may be seasonally scarce; temperatures may vary seasonally; but none of these factors necessarily restricts growth, as the bones and teeth of most living ungulates show. Furthermore, cold-weather mammals brought inside for the winter and fed well still deposit rest lines, suggesting that these lines are at least in part endogenous—as they are in crocodiles (Buffrénil 1980).

Today's dinosaurs—birds—do not have LAGs for a simple reason: they reach adult size before LAGs would be deposited. Most small birds reach adult size in 6–12 weeks or less, and they sustain rapid growth until they reach full size. Most of these are passerines and other small species, but even the kiwi, which grows more slowly than do most birds, reaches full size in less than a year (Reid and Williams 1975), and tinamous do so in 28 weeks (Bohl 1970). Many small birds do not deposit fibro-lamellar tissue like that in larger birds and other dinosaurs, so it is difficult to compare them with larger birds. However, even some small birds are known to deposit LAGs that are decidedly not annual (Van Soest and Van Utrecht 1971; Klevezal et al. 1972). Even among large birds that deposit fibrolamellar tissue, the rhea and the ostrich reach adult size in less than a year (Bertram 1992), too short to reflect an annual LAG.

LAGs are known to be annual in some living tetrapods, although skeletochronology is not always so straightforward. In fossil taxa, LAGs are sometimes merely assumed to be annual, but this assumption can be tested. In Maiasaura, for example, the thickness between successive LAGs in the larger long bones is consistent with what would be expected in a year, based on the rates of deposition of the particular kind of fibrolamellar tissue seen in living animals (Horner et al. 2000). However, it appears that a LAG was not deposited during the first year, presumably because the animal was growing so quickly. We expect that this was the case for large dinosaurs in general, although smaller ones had a decidedly different growth regime (Padian et al. 2001b).

Chinsamy and Hillenius (this vol.) argue that fibrolamellar bone interrupted by LAG suggests an alternating/fluctuating physiological condition, which would come from poikilothermy or heterothermy. This hypothesis can be tested by looking at extant animals in which LAGs are deposited. As noted above, although living birds apparently reach maturity too quickly to deposit LAGs, this is mainly because they are too small. But both the Eocene giant anseriform relative Diatryma and the Pleistocene giant ratite Dinornis (both members of the crown clade of birds, and therefore presumed endothermic) deposited LAGs that are identical to those inferred to be annual in extinct large nonavialan dinosaurs (Horner et al. 1999; Ricqlès et al. 2001). We infer from these data that, if crown group birds evolve a sufficiently large adult size, they will deposit LAGs if they take over a year to reach maturity. No one has proposed that Diatryma and Dinornis were poikilothermic or heterothermic, however, and such physiological limitations cannot be claimed for the elk, a living mammal—known to be endothermic—that also deposits LAGs and takes more than a year to mature (Horner et al. 1999). Thus the view that LAGs by themselves necessarily show anything about physiological regime is falsified.

Growth Rates

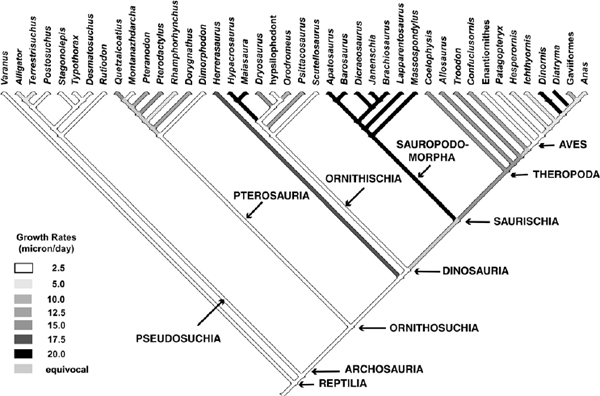

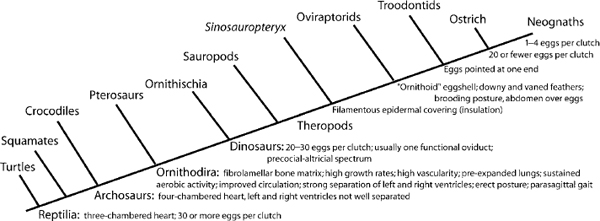

As Amprino's Rule states, the kind of bone tissues deposited directly reflects the rates at which they are deposited (Amprino 1947). Large Mesozoic dinosaurs and pterosaurs deposited well-vascularized fibrolamellar bone throughout their ontogeny, with few exceptions. This is in sharp contrast to the situation for all known pseudosuchians (including crocodylians; fig. 29.3). We assessed the subadult tissues deposited in the bones of a variety of living and extinct archosaurs, and compared the growth rates of these tissues with those observed in living birds (Castanet et al. 1996, 2000). Our only assumption is the actualistic one that a given kind of tissue is deposited at the same approximate range of rates, regardless of the taxon (Amprino 1947). We then superimposed these inferred growth rates, which are no more than a summary of the distribution of tissues at the subadult stage, on a standard phylogeny of archosaurian reptiles (fig. 29.3). These rates were based on observed rates of growth in some living bird tissues (Castanet et al. 1996, 2000). Since these rates were calculated, new work in the same laboratory has shown substantial overlap in growth rates—indeed, often much higher growth rates than first observed (60–100microns per day or more) in some tissues of the fibrolamellar complex (Margerie et al. 2001). Because bones of extinct dinosaurs often comprise the same tissues, it is possible that growth rates were even higher than previously conservatively estimated (Padian et al. 2001b). However, all these fibrolamellar tissues grow substantially faster than do the lamellar-zonal tissues found in pseudosuchians. Our pattern (fig. 29.3) would be falsified if extensive overlap between fibrolamellar and lamellar-zonal growth rates were systematically identified.

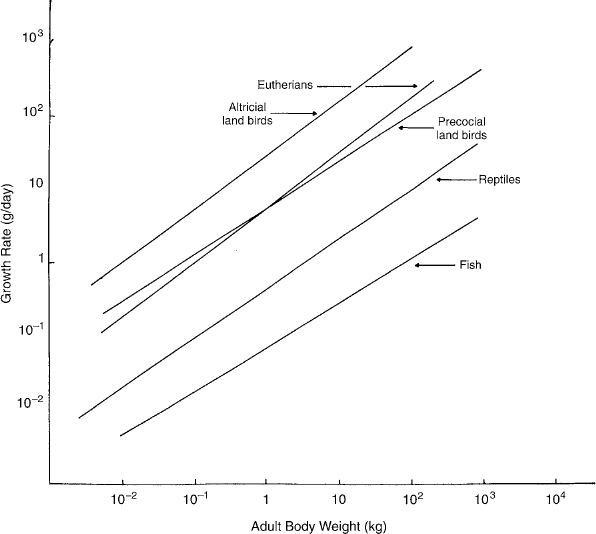

The results are straightforward. Pseudosuchian archosaurs, even large ones, grew at much slower rates than ornithosuchian archosaurs of the same size. Although it is an inference to suggest that such sustained high growth rates were probably supported by high basal metabolic rates, we know of no other explanation, and none has yet emerged from physiological studies. In apparent contradiction to our generalization, some members of the ornithosuchian lineages grew at lower rates did than others. These are smaller members of their lineages, which, as Case (1978a) noted, tend to grow more slowly to their smaller adult size than do larger taxa (fig. 29.4). Hence, their tissues should reflect lower growth rates, which we have assigned conservatively. More importantly, however, new stories, such as Margerie et al. (2001), are changing the calibration of some of these rates of tissue growth, although they are not falsifying Amprino's Rule.

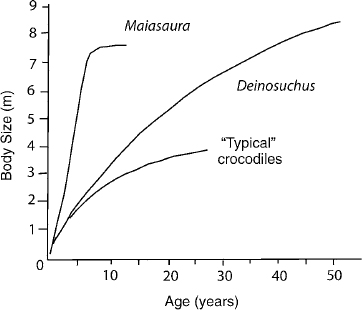

Growth slowed with age in dinosaurs and pterosaurs, as it does in mammals and all other known tetrapods (Horner et al. 1999, 2000; Ricqlès et al. 2000; Erickson et al. 2001). However, in dinosaurs, this growth did not slow until much later in ontogeny than it does in living nonavian reptiles, if the kind of tissue deposited is any indication (Amprino 1947). Slowed growth is reflected by reduced vascularization, predominance of longitudinal canals to the near exclusion of radial and circumferential canals, less space between successive LAGs (which may not appear at all in early growth stages), a permanent layer of endosteal bone deposited along the perimeter of the marrow cavity, and the onset of a nearly avascular layer, the external fundamental system, beneath the periosteum (Cormack 1987; Castanet et al 1993; Reid 1996). The growth curve of a large dinosaur, such as Maiasaura, reconstructed from its bone tissues (Horner et al. 2000), is qualitatively different from that of crocodiles, even large crocodiles, such as the Cretaceous Deinosuchus (fig. 29.5; Erickson and Brochu 1999). Therefore, not only is the sustained deposition of fibrolamellar bone important; it provides the only evidence we have of the rates at which dinosaurs actually grew. Finally, inasmuch as sustained skeletal growth is only found in animals with sustained high metabolic rates, such as living birds and mammals, it is difficult to avoid the conclusion that the metabolic rates of the dinosaurs that produced such sustained high growth rates must have been energetically more like birds and mammals than like typical reptiles of today.

Finally, concerning the metabolic status of some Mesozoic birds, we conclude that the histological features of their long bones suggest not the incomplete evolution of endothermy (e.g., Chinsamy et al. 1995), but the slowdown of growth rates, a strategy that basal birds used to become miniaturized relative to their larger theropod relatives (Erickson et al. 2001; Padian et al. 2001b; Ricqlès et al. 2001). The previous conclusion of incomplete endothermy was based on examination of the histological profiles of parts of sampled bone cortices at an unknown ontogenetic stage and directly inferring physiological regime from it. In contrast, the latter conclusion is based in both ontogeny and phylogeny; recognizing that birds evolved from rapidly growing theropod dinosaurs, it becomes evident that the bone tissues that reflect a predominance of slowly growing tissues would result in a smaller adult size.

FIGURE 29.3. Cladogram of archosaurian taxa, after various sources, with subadult long bone growth rates superimposed. Darker stem lines denote higher growth rates. Rates were based on observations of cortical tissues of subadult femora and tibiae, compared with the same kinds of tissues of known growth rate in the mallard, ostrich, and emu. Calibrations, however, are very conservative, based on a range of rates. (Based on Padian et al. 2001b.)

Our inferences about the comparative growth rates of dinosaurs and other living and extinct reptiles are consistent with some predictions from actualistic physiology. Dunham et al. (1989:6) used models that integrate nutritional energetics and life-history variation to approach the problem of how quickly a dinosaur, such as Maiasaura, could have grown to adult size, based on the variables that they could assess. “Even in the absence of limitations due to environmental availability of food, it is unlikely that dinosaurs of the same order of adult size as Maiasaura peeblesorum or larger could have matured in less than about five years.” This is consistent with our projections of about seven years to adulthood for Maiasaura; and, as Dunham et al. note, their model does not depend on ectothermy or endothermy as a physiological model.

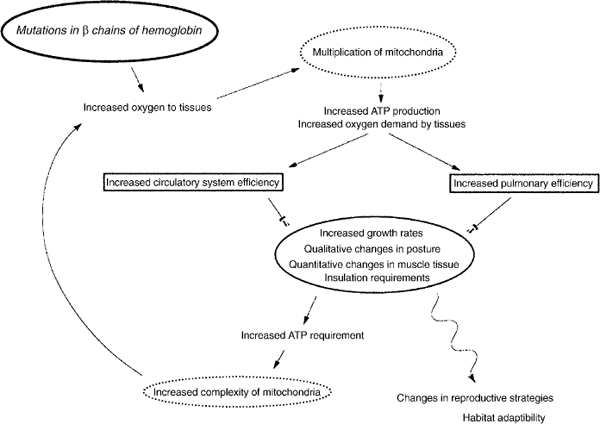

Evolution of Endothermy: A Molecular Model

The long history of commentary on the evolution of endothermy has tended to rely more on knowledge of selective processes than on knowledge of pattern. This is understandable, because there are few—if any—direct lines of evidence about the molecular basis of endothermy that can be preserved in the extinct organisms that would be involved in phylogenetic analyses of metabolic evolution. Recently, however, Schweitzer and Marshall (2001) have provided a molecular model of the evolution of endothermy that is rooted both in molecular process and phylogenetic pattern. Molecular processes, they note, can work across a wide range of body temperatures and basal metabolic rates. However, in endotherms, those processes generally work within a narrower, and higher, set of ranges. Schweitzer and Marshall ask how these rates may have increased incrementally, so as to preserve the functions of integrated organismal systems, and whether phylogenetic evidence can provide any test for hypotheses about metabolic evolution.

In their model (fig. 29.6), mutations in β-hemoglobin chains that bind more negatively charged organophosphates stabilize the deoxy-form of hemoglobin and lower its affinity for oxygen. This allows more oxygen to be delivered to the tissues. Because excess oxygen forms free radicals that are toxic, mitochondria within the cells would multiply to produce higher concentrations of the enzymes that reduce oxygen radicals to water. Increased numbers of mitochondria increase ATP production and accompanying waste heat, and so increase the demand for oxygen. This step would require a more efficient circulatory system, but if the common ancestor of archosaurs had a four-chambered heart, as crocodiles and birds do, then the basis for improvement was already present. Pulmonary efficiency would also need to increase, but as we have noted, ornithodirans probably already had multicameral lungs, because these are generally distributed in reptiles; moreover, they were likely to have been dorsally attached, and this, as Schweitzer and Marshall note, essentially “pre-expands” the lung to a larger volume than in sprawling reptiles, which compress their lungs from side to side as they walk (Carrier 1987; Perry 1992, 1998).

FIGURE 29.4. Within clades of tetrapods, species with larger adult sizes grow more rapidly than those of smaller adult sizes. (From Case 1978a.)

FIGURE 29.5. Comparative growth histories of the hadrosaurid dinosaur Maiasaura and the giant Cretaceous crocodile Deinosuchus, with typical crocodiles for comparison (crocodile data from Erickson and Brochu 1999). Deinosuchus grows slightly more rapidly and extends its active growth curve more than crocodiles, but the curve for Maiasaura, a large dinosaur with respect to its growth profile, is qualitatively different, reaching approximately the same adult size in about seven years, rather than 40 years or more (Horner et al. 1999). Although data on partial growth series have been collected for some dinosaurs (Erickson et al. 2001), none but Maiasaura is currently represented from embryo to adult.

Schweitzer and Marshall describe several consequences of the abovementioned modifications. We have mapped some of these in figure 29.7, along with other features (Padian and Horner 2002: fig. 3), based on a standard phylogeny of Reptilia. First, the ability to grow more rapidly follows from better circulation and pulmonary efficiency, and histological studies show a distinct difference between pseudosuchians and ornithodirans in tissue patterns that reflect growth rates, as noted above (Padian et al. 2001b). A second consequence is the ability to sustain aerobic activity, and from this, improvements in posture, including habitual bipedality, an erect stance, and parasagittal gait. These features are characteristic of basal ornithodirans. Third, muscles would be expected to benefit from increased production of ATP by increasing mitochondrial efficiency, as in living tetrapods. In turn, integumentary insulation that can control the gain and loss of body heat assists metabolic processes to operate at high and constant levels. Feathers and other integumentary coverings are now known to have been present in a variety of nonavialan coelurosaurs, as well as in pterosaurs.

The cumulative effects of these changes, Schweitzer and Marshall say, include the ability to invade new adaptive zones, inhabit less equable climates, and adjust reproductive strategies to fit these environments. The phylogenetic distribution of the features related to metabolic evolution that can be observed in preserved morphology supports their model in several ways. These features include rapidly growing tissues, erect posture, parasagittal gait, bipedality, a four-chambered heart, multicameral lungs, insulatory coverings, and nest brooding using the abdomen (see below).

FIGURE 29.6. Schematic diagram illustrating genetic and epigenetic changes and their possible consequences for structure, metabolism, and behavior. (From Schweitzer and Marshall 2001.)

FIGURE 29.7. Cladogram mapping of some of the features discussed in the text on a phylogeny established on other characters from the skull, vertebrae, girdles, and limbs, and others inferred from molecular changes manifested in the skeleton (see Padian and Chiappe 1998b; Schweitzer and Marshall 2001). This transformational approach clarifies which features are really peculiar to birds, and which were already present in nonavian ornithodirans. It also suggests that most features associated with endothermy were already present before the origin of birds.

Reproduction and Behavior

Given how difficult it is to preserve soft tissues in extinct dinosaurs, it is all the more surprising that we know as much as we do about some aspects of their reproductive biology and their behavior. As far as is known, all dinosaurs laid eggs (and continue to do so today), and the presence of identifiable embryos in some fossil eggs has permitted us to associate many kinds of eggs, which have diagnostic shell microstructures, with particular groups of dinosaurs (reviews in Carpenter et al. 1994b; Horner and Dobb 1997; Mikhailov 1997b; Carpenter 1999). These features, like any others, can be interpreted within a phylogenetic framework. This approach provides the only known method to assess characteristics in evolutionary context.

Eggs and Clutches

Only nonavian theropods and living birds have the same “ornithoid-ratite” eggshell morphotype (Moratalla and Powell 1994). It is not true that retaining two functional ovaries and oviducts is a crocodilian feature, because paired ovaries have been recorded in at least 86 species of 16different orders of birds; and although usually only the left oviduct is functional, ducks with two functional ovaries have been known to lay two eggs in one day (Welty 1979).

Nor is it true that the number of eggs in nonavialan dinosaur clutches is reptilian and suggests that dinosaurs were r-strategists. Crocodiles lay from 30 eggs (American alligator; Goodwin and Marion 1978) to 32–43 eggs (American crocodile; Lutz and Dunbar-Cooper 1984) up to 80 eggs (Nile crocodile; Pooley and Gans 1976) in a clutch, and crocodiles are far smaller than most dinosaurs (such as sauropods, hadrosaurs, and theropods) that lay far fewer eggs. Whereas some birds lay as few as one or two eggs, the ostrich major hen lays an average of 11 eggs, and the mean number of incubated eggs in the nest (including those from minor hens) is 19 (Bertram 1992). Under the circumstances, it is difficult to regard known nonavialan dinosaur clutch sizes as “reptilian” (oviraptorid, 22; troodontid, 22–24; tyrannosaurid, 26; titanosaurian, 6–20; Maiasaura, 16; lambeosaurine, 22), when their numbers are closer to those of large birds than to those of crocodiles. Furthermore, ostrich eggs, like those of the much smaller kiwi, are about the same size as those of Maiasaura (Horner 1999) and known sauropods (Chiappe et al. 1998a), the alligator, and Troodon (in descending order), but not nearly as large as those of lambeosaurines (Horner 1999). Hatching size (as a percentage of adult size) in the nonavialan dinosaurs closest to birds (oviraptorids and troodontids) is large, as in birds; not small, as in other reptiles. The phylogenetic patterns suggest that the retention of clutches of up to two dozen large eggs is a plesiomorphic feature of birds that was inherited from nonavialan theropod ancestors. So are the habits of laying asymmetrical eggs and retaining two functional ovaries (based on troodontids, which are phylogenetically closer to birds than are oviraptorids). This phylogenetic view, we think, explains the distribution of evidence better than a typological approach does.

Parental Care and Growth Strategies

The hypothesis that some dinosaurs provided extended care to their altricial young (Horner and Makela 1979; Horner 2000; J.R. Horner et al. 2001) does not have direct implications for endothermy, but indicates a growth strategy that is known only in extant endothermic animals. Altricial and semi-altricial young are provided food that they do not have to expend energy to acquire, and they use that saved energy to grow rapidly. Young crocodilians and other extant nonavian reptiles would likely also grow at a much faster rate if they, too, were afforded free food, as shown by captive crocodilians raised under optimal conditions. It is unlikely, however, as our previous discussion of growth rates and bone histology shows, that parental feeding of ectothermic reptiles would allow growth rates commensurate with those of Dinosauria, and in particular, Theropoda (J.R. Horner et al. 2001).

Whether dinosaur nesting behavior supports an endothermic physiology is not straightforward, first because it is variable (as it is in birds and other reptiles), and second, because evidence for it is indirect. Repeated examples of oviraptorids and troodontids squatting on nests of eggs with arms spread (Norell et al. 1995; Dong and Currie 1996; Varricchio et al. 1997; Clark et al. 1999) indicate that these animals were incubating the eggs, using their bodies to warm them. Geist and Jones (1996) purported to find more similarities here with crocodiles and other reptiles than with birds, and stated that the incubating syndrome is widely distributed among extant tetrapods. Again, this is a typological confusion of plesiomorphic and derived features. The oviraptorid is not resting its forward end on a nest mound like a crocodilian or wrapping its body around its eggs like a python, but is sitting with its abdomen centered directly on top of a neatly arranged clutch of eggs, identical to brooding birds. Its feet are tucked beneath the body and the (apparently feathered) forelimbs are spread to cover the eggs. To overlook this position, and comment only on generalized behaviors that relate to extant nonavian reptiles and amphibians, is not only typological but mistakes one end of the animal for the other (Horner et al. 2001), therefore voiding the alleged similarity.

Furthermore, incubating (warming eggs by any means) is not the same as brooding (warming with body heat). Animals that cannot radiate sufficient body heat or are too large to sit on their nests without breaking the eggs must use means other than body heat to warm eggs. Therefore, an animal that sits on its nest must, prima facie, be contributing heat. As pythons show, it is possible to brood eggs without being endothermic in the traditional sense. And, as maiasaurs, lambeosaurines, and other large dinosaurs show, it is possible to incubate eggs without using body heat—although this does not imply ectothermy, as the highly derived nest constructions of megapode birds show. (Megapodes do not brood, but they turn their asymmetrical eggs in their burrows, which range in depth from 30 cm to 3 m of vegetal and soil cover [Jones et al. 1975]. There is no reason why troodontids could not have done the same.) Given a theropod dinosaur known to have feathers (as oviraptorids and other basal, as well as derived, maniraptorans have) and sitting in the exact position on a nest that birds do today, why is it reasonable to compare this dinosaur to a crocodile?

Dinosaur reproductive behavior, as interpreted from taphonomic occurrences and comparative methodology, provides no contrary evidence for dinosaur endothermy. Instead, the similarities in brooding position to those of extant birds, and in the degree of ossification of limb bones to those of altricial or semi-altricial bird hatchlings, reinforce the hypothesis that some configuration of endothermy existed within extinct Dinosauria. These conclusions are not based on isolated similarities but on derived similarities set in a phylogenetic context. This method contrasts sharply with that of typologists, who either search for similarity with primitive taxa or search for differences from derived taxa. But typology cannot produce data relevant to ancestry or evolutionary patterns, because it produces not patterns, but unstructured pairwise comparisons.

Conclusions

Formulations that see no reason to regard dinosaurs as anything other than reptiles are typological. That is, they are based on the assumption of no departure from what is assumed to be a primitive condition in the lineage that separates dinosaurs from other reptiles. Even if Mesozoic dinosaurs were no different than reptiles of today, the typological method is inadmissible as support for this conclusion.

However, there are good reasons to think that Mesozoic dinosaurs were more like today's birds and mammals than they were like today's reptiles. They were, possibly, “damn good reptiles,” as Farlow (1990) cogently argued in his summary of the topic; but then, so are birds. We provide a summary of evidence from bone tissues that shows that dinosaurs were nothing like reptiles in growth rates (and, we argue, in supporting metabolism), but like large birds and mammals in these respects (see also Padian et al. 2001b). We also show why some indicators of growth, such as growth lines, are not reliable guides for the interpretation of physiology, based on living animals. Further discussion of these points can be found in J.R. Horner et al. (1999, 2000, 2001) and Ricqlès et al. (2000, 2001), and a brief review of more traditional arguments is in Padian (1997b). It is not necessary to postulate that these dinosaurs were exactly like today's birds and mammals, any more than it is to postulate that they were exactly like today's reptiles. However, there is no convincing evidence that these dinosaurs were like today's reptiles in any important respects.

The typological approach to inferring soft-tissue anatomy, function, behavior, and physiology in extinct animals has little utility in an evolutionary framework (Padian 1995b; Witmer 1995a). Because there are no “Rosetta Stones” or “magic bullets” of structure in fossil vertebrates that unequivocally constrain or indicate metabolism and physiology, hypotheses about these properties and their evolution should logically be tested by independent lines of evidence, with recourse to phylogenies of the lineages in question. Moving from a known basal state to a known derived state, the physiologically diagnostic characters of the taxa in a lineage can be identified as they are assembled evolutionarily in the lineage. Otherwise, there is no accepted method of testing a hypothesis about the evolution of a particular physiological or behavioral feature. Dinosaurs cannot be regarded simply as “good reptiles,” because they have a great many features that “typical” reptiles lack and that are identified with higher rates of growth and metabolism. The burden of evidence, it seems to us, is on those who see the glass as less than half full.