3 What would a post-drug-war world look like?

AS INCREASING NUMBERS of people have realized that prohibiting drugs has failed, a parallel debate has emerged about what other approaches might work better. If prohibition doesn’t work and often makes things far worse, only retaking control of the market from criminals and bringing it within the control of the state, can, in the longer term, substantially reduce many of the key costs associated with the illegal trade, and deliver the improved outcomes that we all hope for.

Prohibition has always had an ideological focus on reducing or eradicating drug use, the ultimate goal being the achievement of a ‘drug-free world’. All other aims have become secondary to that goal, no matter how hopelessly unrealistic and unachievable it clearly is. By focusing so narrowly, often almost obsessively, on the fantasy of a ‘drug-free world’, wider policy goals, in health, human rights and social development, have been marginalized, or lost entirely.

This is why it is vital to emphasize from the outset that the overarching aim of drug policy (and indeed, any policy) should be to minimize social and health harms, and to maximize wellbeing. While the goal of reducing harms certainly overlaps with one of reducing use, they are not the same. Working towards reducing harm would shift the focus of policy from reducing use per se to reducing problematic use (in other words, use that creates significant negative impacts for the user or those around them). It also means that harms beyond those associated merely with drug use would be factored into policy-making decisions – including those associated with the criminal-controlled drugs market and with drug law enforcement itself, such as mass criminalization and incarceration.

Within this broader general goal of reducing harms, a series of sub-aims can be identified. Key among these are:

• Protecting and improving public health

• Reducing drug-related crime, corruption and violence

• Improving security and development

• Protecting the young and vulnerable

• Protecting human rights

• Basing policy on evidence as to what works, and what provides good value for money.

Regulation: the pragmatic middle-ground

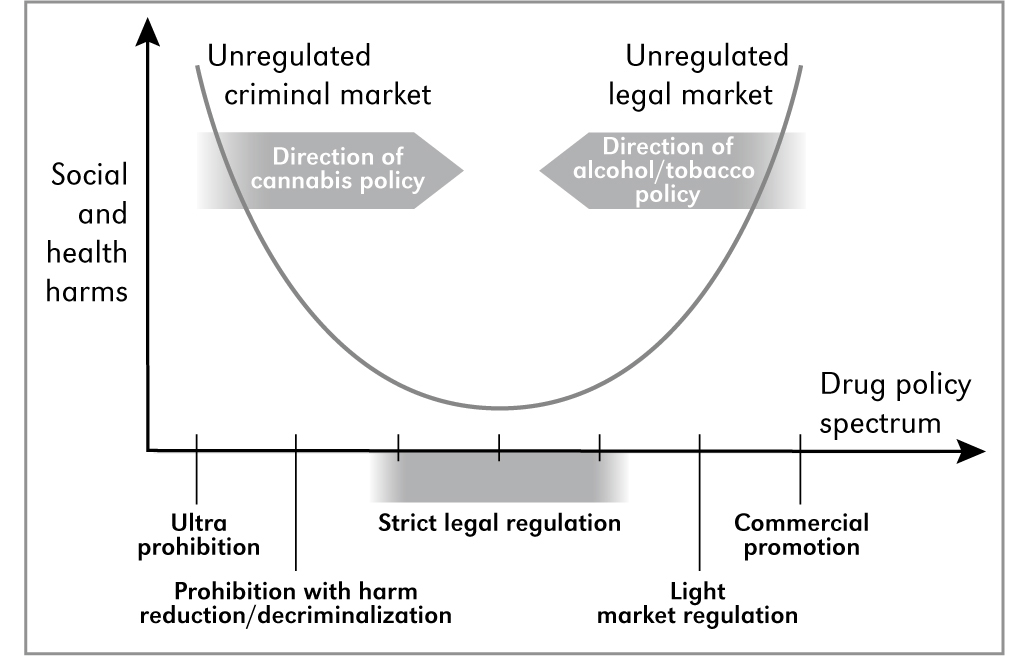

Having clarified what the goals of drug policy should be, the question is then: which policy model can most effectively deliver them? The central argument for a regulated legal market is summarized by the graphic below, positioning it as the middle-ground option on the spectrum between illicit markets controlled by criminals, and legal markets controlled by profit-seeking corporations.

Strict legal regulation: the healthy middle-ground

Definitions

Prohibition describes policy and law under which the production, transit, supply and possession of certain drugs for non-medical or scientific purposes is illegal, and therefore subject to punitive sanctions, including criminal penalties. Although the three United Nations drug conventions – the legal bedrock of the global drug-control regime – define such prohibitions for specified drugs as global in scope, the domestic laws, enforcement approaches, and the nature of sanctions applied for different offenses, and for different drugs, vary significantly between jurisdictions.

Legalization is a process by which the prohibition of a substance is ended, allowing for its production, availability and use to be legally regulated. ‘Legalization’ is, however, merely the process of legal reform, rather than a policy model in itself; the nature of the regulation model that follows needs to be specified separately.

Regulation of a market describes the way in which government authorities intervene to control a particular legal drug product, or activities related to it. This control can take the form of regulations on, for example, a drug’s price, potency, and packaging, as well as various aspects of its production, transit, availability, marketing and use. Products or activities that sit outside of the parameters of a regulatory framework (such as sales to children) remain prohibited and subject to punitive sanctions. There is no single regulation model; there are a range of regulatory tools that can be deployed in a variety of ways, depending on the product, and the context of its availability and use.

Decriminalization is not a clearly defined legal term in drug-policy discourse (and is often mistakenly confused with legalization). It is most commonly understood to refer to the removal of criminal penalties for the possession of small amounts of certain specified drugs for personal use. So when you hear the phrase ‘decriminalization of drugs’, it more accurately means ‘ending the criminalization of people who use drugs’. Under a decriminalization approach, possession remains an offense that can still be subject to a civil or administrative sanction such as a fine or mandatory treatment assessment. There is considerable variation in how decriminalization is implemented in different jurisdictions, in terms of quantity thresholds (which distinguish between possession for personal use, and possession with intent to supply), the nature of civil sanction, how sanctions are enforced, and by whom (the police, judges, social workers, or health professionals). Unlike legalization and regulation, decriminalization of this kind is permitted within the UN drug conventions. Decriminalization generally refers to possession of drugs for personal use but is sometimes applied to other less serious drug offenses, including cultivation of cannabis for personal use, or small-scale not-for-profit drug supply or sharing.

Either end of this spectrum involves effectively unregulated markets: the criminal markets of total prohibition at one end, and legal, commercial free markets at the other. At both these extremes, profit is the primary focus of the market, with other outcomes of little importance. This inevitably leads to high levels of avoidable social and health harms, as those in control of the market prioritize profits over the public good, and take no responsibility for the externalities of the drug trade.

Given the reality of continuing high demand for drugs, and the resilience of illicit supply in meeting this demand (in other words, the abject historic failure of prohibition) regulating drugs as we do other dangerous or potentially harmful substances looks like the best option by far. It is here, at the bottom of this U curve, where an optimum level of government regulation lies – a point at which policy is both ethical and effective, because it represents where overall harms are minimized.

As well as identifying the need to move towards responsible regulation of currently prohibited drugs, this way of considering the various options also highlights the need for better regulation of currently legal drugs, where over-commercialization is leading to avoidable harms. The destination – optimum regulation that minimizes social and health harms – is the same, even if the starting point is different. Viewed in this way, the legalization and responsible regulation of currently illegal drugs is no longer an extreme position, but can instead legitimately claim to represent the pragmatic center-ground position, sitting comfortably with parallel calls for stricter regulation of tobacco and alcohol.

Regulation is, in its simplest formulation, the way in which government authorities intervene in the market to control a particular legal drug product, or activities related to it. It is fundamentally about the management and minimization of risk. Such regulation of risk is one of the primary functions of government, and is all around us: product safety regulation such as flame-retardant mattresses, or preventing choking hazards on toys; food regulation such as ingredient monitoring and labelling requirements; regulation of which vehicles we can drive, how fast, and where; controls on who can use certain machinery, who can buy and use certain fireworks, and so on.

Pharmaceuticals are also regulated and, more pertinently for this book, so too are legal alcohol and tobacco products with, for example: controls on the alcohol and nicotine content; information and warnings on the packaging; age controls on who can buy; where they are sold and consumed and how they are marketed.

When you look at it in this way, the legalizing and regulating of adult access to and use of drugs stops being something radical or strange, and becomes something obvious and normal. Punitive prohibitions are the ‘radical’ policy response – not regulation. Regulating drugs is simply a case of applying the regulatory principles and mechanisms that are routinely applied to everything else, to certain risky products and behaviors that (for irrational historical reasons explored in Chapter 1) have previously been controlled entirely within a criminal economy.

As with markets for other products, all aspects of a drug market can be regulated – from production through sales to consumption. Regulation means establishing the rules and parameters for what is allowed within these different elements of the market, and then ensuring that the rules are complied with. Activities that take place beyond these parameters, such as sales to children, or inaccurate packaging information, would remain prohibited and subject to a hierarchy of proportionate sanctions. Just as we already do with alcohol and tobacco, this could involve civil or administrative sanctions such as fines, or loss of a vending license, only graduating to criminal sanctions for more serious offenses or violations.

This understanding of legalization and regulation stands in contrast to some popular misconceptions that legalizing drugs inevitably implies ‘relaxing’ control or ‘liberalizing’ markets. In fact, it involves rolling out state control into a market sphere where currently there is little or no control whatsoever, and establishing a clearly defined role for enforcement agencies in managing any newly established regulatory model.

It is certainly true that some free-market libertarian thinkers have gone further, arguing for what is sometimes called a ‘supermarket model’. Under this scenario, all aspects of a drug’s production and supply would be made legal, with regulation essentially left to market forces, except for the sort of basic consumer-product controls we are used to for products available in a supermarket – things like truthful lists of ingredients, and ‘sell by’ dates. While a free-market model remains a feature of the debate, demarcating one extreme end of the spectrum of options, it has very few advocates and is more useful as a thought experiment to explore the perils of inadequate regulation.

In terms of the actual mechanics of a regulation model, the production of drugs and their transit to sale are perhaps the simplest parts of the regulatory challenge. Many of the ‘illegal’ drugs being considered – such as amphetamines, cocaine and various opiates, including heroin – are already produced legally for medical uses, as a look through the secure cabinet in any hospital emergency room will quickly reveal. The UN drug conventions that form the bedrock of global prohibition on non-medical use also provide the framework for the legal production of the same drugs for medical uses. These extensive medical-production models operate without significant problems and indicate clearly how production of both plant-based and synthetic drugs can be carried out in a safe and controlled way.

There is a striking difference between the minimal harms associated with these legally regulated medical markets, and the multiple costs associated with the criminally controlled non-medical markets for the same products. This contrast is demonstrated most starkly by the example of heroin. This is widely regarded as one of the most risky and problematic of all illegal drugs when used non-medically, but is also one of a number of vitally useful and entirely legal medicines derived from the opium poppy, and used by doctors around the world for pain control.

Of global opium production, half is entirely legal, produced under license for refining into opiate medicines, including pharmaceutical heroin (diamorphine). Fields of the very same opium poppies that are grown illegally in Afghanistan and Mexico are also grown legally across the world, in England, Spain, Turkey, India, Australia and at least 13 other countries. This regulated opium production – and the processing of some of it into legal pharmaceutical heroin – is not associated with any of the crime, conflict and chaos of the parallel illegal market for the same drug.

Regulating availability and use arguably presents a greater challenge. To break this down, legal regulation allows controls to be put in place over:

• Products (dosage, preparation, price, and packaging)

• Vendors (licensing, vetting and training requirements)

• Marketing (advertising, branding and promotions)

• Outlets (location, outlet density, appearance)

• Who has access (age controls, licensed buyers, access based on club membership)

• Where and when drugs can be consumed (restrictions on consumption in public places).

It is again worth pointing out that we have extensive practical experience in precisely this sort of drug regulation. The World Health Organization’s Framework Convention on Tobacco Control, for example, provides a useful template for how international best practice in trade and regulation for non-medical use of a risky drug can be developed, implemented and evaluated.1 Strikingly, the tobacco control convention features a level of support from UN member states comparable to that for the three prohibitionist UN drug conventions – despite their serving a purpose that could not be more different in principle or in practice.

There is no single regulation model for ‘drugs’; there are a range of regulatory tools that can be deployed in a variety of ways, depending on the risks of a particular product.

The political and social context in which the availability and use of a particular drug is being considered will inevitably shape the nature of the models that are developed. We have seen, for example, very different models of cannabis regulation emerging in different political and social environments, such as Uruguay, Spain and Colorado (see page 80). A key point to emphasize is that management of drug availability by responsible government authorities ensures that regulation can be deployed at different levels of intensity, depending on the risks of a given product or activity, or the needs of a particular local situation.

Naturally, the riskier a drug, the stricter the controls we would see: we would expect, for example, injectable heroin to be subject to far more stringent controls than cannabis. This ability to vary the intensity of regulatory controls allows us to create an ‘availability gradient’ that corresponds to the varying risks of different drugs, behaviors and environments in which they are consumed.

This availability/risk gradient can support broader public-health goals by progressively discouraging higher-risk products, preparations and behaviors, ‘nudging’ patterns of use towards less risky avenues, and, in the longer term, fostering social norms around more responsible and less harmful use. Illicit drug markets are not neutral in this regard; in many instances they actively push use in the opposite direction, towards increasingly harmful products and practices.

There are five basic models for regulating drug supply/availability, all of which have been used for various existing products and markets.

• Medical prescription – The riskiest drugs, such as injectable heroin, can be prescribed to people who are dependent via a qualified medical practitioner. Heroin prescribing is a well-established and highly effective model of legal drug availability that has been used in a number of countries (see page 85-9). Similar approaches have been used with some stimulants, including amphetamines, as well as with opiate substitutes such as methadone and buprenorphine. This model can include extra tiers of regulation, such as requiring that drug consumption takes place in a supervised venue.

• Pharmacy sales – This is essentially a retail model in which licensed and trained professionals serve as gatekeepers to a range of drugs, in a similar way to over-the-counter sales in a pharmacy. The vendors are required to enforce access controls (such as restrictions on age and sales volume), but would also be trained to offer advice on risks, safer use, and access to services where needed. This model could be appropriate for medium-risk drugs – stimulants used in the party scene, for example, such as MDMA. Drugs would be sold in functional, non-branded packaging (as prescribed drugs presently are) with risk and health information mandated.

• Licensed sales – This is a more conventional sales model, similar to how the licensed retailing of alcohol operates in many countries. Such licensed outlets could sell lower-risk drugs, such as cannabis, magic mushrooms, or some lower-potency stimulants. All sales would be in accordance with strict licensing conditions established and enforced by a dedicated regulatory authority. These could include price controls and taxes, responsible vendor training, restrictions on advertising and promotion, age restrictions, and health-and-safety information on product packaging.

• Licensed premises for sale and consumption – Similar to pubs, bars, or Dutch cannabis ‘coffee shops’, licensed premises could sell lower-risk drugs for on-site consumption, subject to strict licensing conditions similar to those listed above for licensed sales. Additional regulation, such as restrictions on sales to people who are intoxicated and partial vendor liability for customers’ behavior, may also be enforced.

• Unlicensed sales – Drugs of sufficiently low risk, such as coffee or coca tea, require little or no licensing, with regulation more like conventional food products. The only requirement would be to ensure that appropriate production practices and trading standards were followed, and that product descriptions and labelling (which includes, for example, ‘use-by’ dates and ingredient lists) were accurate.

Institutions for regulating non-medical drug markets

Establishing new, legally regulated markets for currently illegal drugs will require a wide range of policy decisions to be made, and new legal, policy and institutional structures to be established in different tiers of government: international (global and regional agencies – such as the UN or EU); domestic (federal and devolved); and various tiers of local government (state, county, municipality, etc). A key challenge, therefore, involves determining which existing or new institutions should be given responsibility for decision-making, implementation and enforcement of the various aspects of regulation. In principle, these challenges do not significantly differ from similar issues in other arenas of social policy and law related to currently legal medical and non-medical drugs, including alcohol, tobacco and pharmaceuticals.

A hierarchical decision-making structure means that tensions will inevitably emerge when lower-level decision-making authorities choose to go against the will of higher-level authorities, or vice versa. Examples of such tensions have been seen with pioneering cannabis reforms now under way: Uruguay’s cannabis-regulation model breaching the UN drug conventions; the Washington and Colorado state models being implemented in conflict with US federal law; and an array of local initiatives on cannabis regulation, including in Copenhagen, more than 60 municipalities in The Netherlands, Mexico City and Spain’s Basque country, that are challenging national-government positions. In a scenario in which the global, federal or state governments are showing little inclination to lead on reform, these tensions are inevitable. Such challenges will eventually lead to reform at federal and UN level, at which point any tensions will be dramatically reduced, even if, to some extent, they remain part of the landscape.

International

There will be a clear and important role for the various UN legal structures and agencies in global drug policy. Key functions for the UN will be:

• Overseeing issues that relate to international trade. As well as the UN, there will be a role for regional agencies such as the European Union, ASEAN, the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), or any dedicated regional or bilateral trade agreements that emerge to serve new markets.

• Assuming responsibility for more general oversight of relevant human rights, labor laws, development and security issues. This role will, however, inevitably change from one of overseeing a global prohibitionist system to one more like the UN role with regard to legal drugs and pharmaceuticals, with UN agencies providing the foundation, ground rules and legal parameters within which countries can or should operate.

• Acting as a hub of research on health issues and best practice in drug policy and law. This research and advisory role will mirror the WHO’s existing role in relation to tobacco and alcohol policy, and will work in partnership with equivalent regional and national research bodies, such as the European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction. At a later stage this analysis and best-practice guidance could potentially be formalized in an international agreement similar to the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control.

Aside from the necessary bureaucratic and legal reforms, the change in focus from punitive enforcement towards pragmatic public-health management clearly indicates that lead responsibility for drug-related issues should move from its current home with the UN Office on Drugs and Crime (essentially a law-enforcement agency), to the World Health Organization and sit alongside its existing role for alcohol and tobacco. It is also likely that the UN-level renegotiation of international law that wider drug reforms will necessitate (already beginning with cannabis) will involve reconsidering a range of human rights issues relating to, amongst other things, the right to privacy (use of drugs in one’s home), the right to freedom of belief and practice (religious or spiritual use of drugs), the right to health (access to drugs for medical use, and access to health information for non-medical use), and proportionality in sentencing. These are likely to have global implications in terms of ending or calling for an end to the criminalizing of personal use of drugs. It is important to make clear, however, that reforms of international law to end the criminalization of people who use drugs will not require governments to make legally regulated drugs available. Such decisions will remain in the hands of individual governments.

National government

Individual jurisdictions will need to determine their own drug-regulation policies and legal frameworks within the international legal parameters, rights and responsibilities established by the UN, and other international bodies or federal governments to which they belong.

Any new overarching parameters agreed at the UN level would set basic standards of justice and human rights, with implications for the use of punitive sanctions against people who use drugs. In contrast to the current prohibitionist framework, these parameters would neither impose nor preclude particular options relating to legal access and supply, or internal domestic drug markets. At the national level, responsibility for decision-making and enforcement of regulation most naturally sits alongside comparable institutional frameworks for alcohol and tobacco. This responsibility, as at the UN level, will logically sit with the government department responsible for health, rather than with that for criminal justice as under the old prohibitionist models.

That said, it is important to be clear that drug policy and regulation, as with alcohol and tobacco regulation, involve a range of agencies and government departments. For example, criminal-justice agencies (including police and customs) will still have a key role in enforcing any new regulatory framework, because those who operate outside it will still be subject to punitive sanctions; departments of foreign affairs and trade will oversee international trade issues and trading standards; departments of education will be involved in public and school-based education and prevention programs, and treasury departments will be involved in tax collections and budgeting. So while the lead role will fall to the health department, some form of national-level entity or co-ordinating body with a cross-departmental brief will be essential. This could involve drug regulation becoming a new responsibility for an existing agency, as has happened in Washington State, where regulatory decision-making on cannabis policy has been delegated to the State Liquor Control Board. Alternatively, it could become the responsibility of a new, dedicated agency, as is the case in Uruguay, where legislation has established a new Institute for the Regulation and Control of Cannabis.

Local government

The micro-level detail and decision-making around how regulatory frameworks are implemented and enforced at the local level will largely fall to local or municipal authorities. These local responsibilities will include most decisions around the licensing of vendors and retail outlets (such as where outlets can be located, and their opening hours), as well as inspection and policing priorities.

This localized decision-making should provide democratic opportunities for local communities to have an input into licensing decisions, as they often do with alcohol sales and venue licensing. The prospect of ‘NIMBYism’ (‘Not In My Back Yard’ opposition) is a realistic one that will need to be dealt with sensitively. It may well be that some communities democratically determine that they do not wish to have some or any legal drugs available from retail outlets within their geographical boundaries, even if possession and use is legalized nationally and legal supply is available in neighboring communities. This has happened in ‘dry’ counties in the US and Australia, and also with medical cannabis dispensaries at the county level in the US, and coffee shops in different Dutch municipalities.

Addressing key concerns around legalization and regulation

Risks of unintended negative consequences exist for any policy change, and, while experience with regulating other drugs can provide clear guidance, it is important to acknowledge that there is also a lot we do not know. But this is not a change that will happen overnight. Moves toward regulated drug markets would need to be phased in cautiously over a period of months and years, with close evaluation and monitoring of the impacts of any new model. Experimental policy models and pilot projects would be needed, and lessons from these – such as the pioneering cannabis-regulation models emerging around the world – could then inform the body of knowledge available for others as we move forward.

Over-commercialization and profit-led promotion of drug use

One key risk would be that drugs would be made available without adequate regulation and that there would be profit-motivated commercialization and aggressive marketing of newly legalized drugs. Clearly there are profound tensions between the interests of public health (to moderate risky drug use and minimize health harms), and the interests of commercial entities selling drugs (to maximize consumption, sales and profits). While legal corporations are preferable to organized crime groups in that they pay tax (or should do), and are answerable to the law, trade unions and consumer groups, they do also have the freedom and power to market and advertise their products directly to customers in ways that organized crime cannot. Important lessons need to be learned from the successes and failures of different approaches to alcohol and tobacco regulation – companies have to be constrained from seeking more profit by encouraging new consumers to try the products or existing consumers to buy more.

In practice this will entail establishing regulatory frameworks that can prevent the excesses of unregulated marketing of the kind that has proved such a public-health disaster with alcohol and tobacco in the past. We have, for example, grown used to alcohol product brands sponsoring sports teams and music events – aggressively exposing adults and children to positive associations between a risky drug and aspirational, glamorous and healthy lifestyles. The idea that legal drug brands in the future would sponsor sporting events would quite rightly be met with outrage. But remember that tobacco sponsorship of the Olympics continued until as recently as 1984, and alcohol-brand Olympic sponsorship continues today. Even high-speed car racing (with frequent crashes all part of the entertainment) is still routinely sponsored by alcohol brands, which is astonishing in the context of almost 270,000 alcohol-related road fatalities worldwide each year.2 Incorporating these lessons is likely to mean the sort of regulatory controls that are increasingly seen in tobacco control (and outlined in the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control). These have effectively reduced tobacco consumption in many countries, without denying legal access to the market for businesses, or resorting to the criminalizing of users. Other models that could be considered include restricting the size of businesses allowed to participate in a market (to prevent corporate capture, and industry lobbying); restricting market access to benefit or not-for-profit corporations or social enterprises; or even having state monopoly control of part or all of the market. While these may seem unusual options, there are precedents for all of them within existing economies. Russia once had a state monopoly on alcohol production, and state monopolies on alcohol supply remain common, for example across Scandinavia (‘Systembolaget’ in Sweden, ‘Alko’ in Finland, ‘Vínbúð’ in Iceland, ‘Vinmonopolet’ in Norway), and in the Canadian provinces of Quebec and Ontario.

Drugs are ‘no ordinary products’; their unique risks justify a level of state intervention in the market that is over and above that which we might see for groceries. But policymakers also have a unique opportunity to design and implement regulatory models to manage and minimize these risks. They will be working from a blank slate. With this great opportunity comes a responsibility to get it right and not to repeat the mistakes of the past.

Remember that use of drugs that are legally produced and supplied will be qualitatively different in terms of risk from the present hazardous cocktails. Legalized and regulated drugs will be of known quality and potency, will come with dosage and safety information from the vendor and on the packaging. They are also more likely to be consumed in safer, supervised environments that encourage more responsible using behaviors. We have to move beyond the historical preoccupation with reducing prevalence of use and have a pragmatic focus on reducing risky use and overall harm.

Will legalization mean more drug use?

We can say that the goal of policy should be to reduce health harms until we are blue in the face but much of the political discourse remains preoccupied with whether legalization would result in increased use. So what do we know?

Evidence suggests that decriminalizing personal drug possession does not increase use (see page 81). However, under decriminalization, the supply of drugs remains prohibited: legalization is completely different.

When considering the impact of legal regulation, we also need to factor in changes to how drugs are made available and promoted (if at all), and how social and cultural norms around their use might evolve. Legal regulation can take many forms, from free markets to state monopolies, so it is unhelpful to generalize: the devil is in the detail.

Evidence of the impact of legalization and regulation on levels of use comes from a range of sources: tobacco and alcohol regulation (including the repeal of alcohol prohibition in the US); medicines; heroin prescribing; The Netherlands’ de facto legal cannabis market; cannabis social clubs in Spain; recent large-scale, legally regulated cannabis markets in Uruguay; and several US states (see the case studies in Chapter 4).

Evidence from tobacco regulation has shown that comprehensive bans on advertising reduce consumption.3 Similarly, since a greater concentration of alcohol outlets is associated with increased alcohol use,4 controls on the location and density of drug outlets are likely to constrain increases in consumption.

Regulation can also help shape the impact of legalization on social deterrence factors that influence levels of use. So, while a change of legal status could provoke an increase in use among certain groups, responsible regulatory controls can moderate this effect. Adopting such controls for tobacco products, combined with better education and prevention efforts, has fostered a norm of social disapproval for smoking, contributing to a 50-per-cent decline in prevalence in some countries over the past 30 years.5 It was not necessary to prohibit cigarettes, or to criminalize smokers, to achieve this.

Of the growing number of regulated cannabis markets, The Netherlands’ is the most well-established, yet it has prices comparable to the illicit US market. This shows that legalization does not have to mean dramatic price decreases, which could produce large increases in consumption. This, along with age restrictions, advertising bans, and controls on the number and location of outlets, has resulted in The Netherlands having levels of cannabis use comparable with neighboring countries, and substantially lower than the US, despite 40 years of effectively legal availability.

So the extent of any upward pressures on levels of drug use following legalization are likely to be dramatically lower if commercial promotion is resisted, stringent regulations are imposed, and prices are kept relatively high.

Are developing countries able to deal with the regulatory challenge?

Many people argue that, even if the broad case for regulation were accepted, in practice, institutions in many countries do not have the capacity to carry out their existing functions, let alone to regulate drugs. This argument will resonate with many – particularly in the development field. But at its core is a misunderstanding of current realities, and a confusion about what drug-law reform can achieve or is claiming to be able to achieve. The starting point is that, as Chapter 2 made clear, the violence, crime, corruption and instability associated with the illegal drug trade is actively undermining many state institutions, and these are problems either created or fuelled directly by the current prohibitionist approach to drugs. If countries do not have the capacity to regulate drugs adequately, then they will certainly not have the capacity to enforce the prohibition of illegal drug markets in the face of powerful cartels – history has clearly demonstrated that, at least once demand is established, drug prohibition has never worked anywhere. In countries such as Mexico a vicious circle of mistrust is created: the public have little faith in state institutions because they see the impunity with which drug cartels operate, and this in turn means they do not provide institutions with the information and support they need to function. The success, visibility and impunity of cartels undermine both the rule of law and respect for the institutions of law. Criminals can even become role models, corrupting established community values.

These problems are exacerbated when the police or military become dependent on foreign resources (particularly from the US) to fight the cartels. When this happens, priorities are skewed towards those of the funders, reducing the opportunities for states to direct their efforts towards local needs or objectives.

Legalization and regulation, by contrast, can help create an environment that facilitates, rather than impedes, social development and institution-building. As outlined above, drug-policy reform will inevitably be a phased and cautious process, one that allows regulatory infrastructure to be developed and implemented over a period of time, in parallel with wider developments in social policy and institutional capacity.

As with all forms of regulation, drug-market regulation may initially be imperfect, but it can develop and improve over time. And in any case, evidence from tobacco regulation (for example from the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control) shows that positive results can be achieved even with imperfect regulatory systems in developing and newly industrialized countries. The reality is that some form of regulation is preferable to none, which is the position we are in at the moment.

What will all the criminals do?

Another concern often raised is that, if the most lucrative source of illegal income is denied to organized criminals, there will be an explosion in other forms of crime. No-one is suggesting that the sprawling criminal empires involved in drug production and supply will somehow magically disappear overnight, or that the criminals involved will all ‘go straight’ and get jobs selling flowers or working in the local supermarket. This is a classic ‘strawman’ argument.

However, it is equally absurd to suggest that they will all inevitably embark on some previously unimagined and far worse crime spree. There are many examples from around the world of successful conflict resolution and the disbanding of armed groups and militias. Looked at objectively, this argument is a strange one as it effectively says that we should keep prohibition as a way of maintaining violent illegal drug empires, so that organized criminals don’t have to change jobs.

If we followed that logic, we would never take any crime-prevention measures – for example, trying to prevent burglary – in case the criminals involved committed different crimes instead. In reality, the legal regulation of drug markets could remove one of the largest criminal opportunities globally, not just from existing criminals but in future too. Ending the war on drugs holds out the prospect of preventing huge numbers of young people entering a life of crime as the next generation of drug producers, traffickers and dealers.

Crime is, to a large extent, a function of opportunity, and the more drug markets become legal entities, the smaller will be the opportunities available to organized crime. Other criminal activities simply could not absorb the person power currently deployed in the multi-billion-dollar illicit drug market. Even if there is some displacement to other criminal activity, it should not be overstated. The bigger picture will undoubtedly show a significant net fall in overall criminal activity. As opportunities dry up, many on the periphery of the drug trade will move back to the legitimate economy.

Clearly some criminals will seek out new areas of illegal activity, and it is realistic to expect that there may be increases in some forms of criminality – for example, extortion, kidnapping, or other illicit trades, such as counterfeit goods or human trafficking. The scale of this potential ‘unintended consequence’ of reform, however, needs to be put in perspective. As a direct result of being able to invest their drug profits in other activities, organized crime groups have already diversified their business interests extensively in recent years, particularly where they have become the most entrenched and powerful groups.

Moving away from prohibition will, in fact, free up large sums of money to spend on targeting any remaining criminals, whose power to resist or evade law-enforcement efforts will diminish as their drugs income shrinks. Criminal groups will experience diminishing profit opportunities as reforms are phased in carefully over a number of years. During this transition, there may be localized spikes in violence as they fight over the contracting profits. But, if such conflict does occur, it is likely to be a temporary phenomenon, and if it can be realistically predicted it can also be more effectively managed, with problems minimized through strategic policing.

1 See who.int/fctc/en

2 WHO, Global Status Report on Alcohol and Health, 2011, nin.tl/WHOalcohol2011

3 Lisa Henriksen, ‘Comprehensive tobacco marketing restrictions: promotion, packaging, price and place’, Tobacco Control, vol 21, 2011, pp 147-153, nin.tl/BMJtobaccocontrol

4 S Popova et al, ‘Hours and days of sale and density of alcohol outlets:’, Alcohol and Alcoholism, vol. 44, no. 5, 2009, pp 500-516. nin.tl/Popova_impact; National Association of State Alcohol and Drug Abuse Directors, ‘Current Research on Alcohol Policy and State Alcohol and Other Drug (AOD) Systems’, State Issue Brief, 2006.

5 Health and Social Care Information Centre, Statistics on Smoking, England –2013, nin.tl/smokingEng; Australian Department of Health, Tobacco key facts and figures, 2015, nin.tl/tobaccoAus