1

The rise and fall of the Termites: What intelligence is – and what it is not

As they nervously sat down for their tests, the children in Lewis Terman’s study can’t have imagined that their results would forever change their lives – or world history.* Yet each, in their own way, would come to be defined by their answers, for good and bad, and their own trajectories would permanently change the way we understand the human mind.

* The stories of the following four children are told in much greater detail, along with the lives of the other ‘Termites’, in Shurkin, J. (1992), Terman’s Kids: The Groundbreaking Study of How the Gifted Grow Up, Boston, MA: Little, Brown.

One of the brightest was Sara Ann, a six-year-old with a gap between her front teeth, and thick spectacles. When she had finished scrawling her answers, she casually left a gumdrop in between her papers – a small bribe, perhaps, for the examiner. She giggled when the scientist asked her whether ‘the fairies’ had dropped it there. ‘A little girl gave me two,’ she explained sweetly. ‘But I believe two would be bad for my digestion because I am just well from the flu now.’ She had an IQ of 192 – at the very top of the spectrum.6

Joining her in the intellectual stratosphere was Beatrice, a precocious little girl who began walking and talking at seven months. She had read 1,400 books by the age of ten, and her own poems were apparently so mature that a local San Francisco newspaper claimed they had ‘completely fooled an English class at Stanford’, who mistook them for the works of Tennyson. Like Sara Ann, her IQ was 192.7

Then there was eight-year-old Shelley Smith – ‘a winsome child, loved by everyone’; her face apparently glowed with suppressed fun.8 And Jess Oppenheimer – ‘a conceited, egocentric boy’ who struggled to communicate with others and lacked any sense of humour.9 Their IQs hovered around 140 – just enough to make it into Terman’s set, but still far above average, and they were surely destined for great things.

Up to that point, the IQ test – still a relatively new invention – had been used mostly to identify people with learning difficulties. But Terman strongly believed that these few abstract and academic traits – such as memory for facts, vocabulary, and spatial reasoning skills – represent an innate ‘general intelligence’ that underlies all your thinking abilities. Irrespective of your background or education, this largely innate trait represented a raw brainpower that would determine how easily you learn, understand complex concepts and solve problems.

‘There is nothing about an individual as important as his IQ,’ he declared at the time.10 ‘It is of the highest 25% of our population, and more especially to the top 5%, that we must look for the production of leaders who will advance science, art, government, education, and social welfare generally.’

By tracking the course of their lives over the subsequent decades, he hoped that Sara Ann, Beatrice, Jess and Shelley and the other ‘Termites’ were going to prove his point, predicting their success at school and university, their careers and income, and their health and wellbeing; he even believed that IQ would predict their moral character.

The results of Terman’s studies would permanently establish the use of standardised testing across the world. And although many schools do not explicitly use Terman’s exam to screen children today, much of our education still revolves around the cultivation of that narrow band of skills represented in his original test.

If we are to explain why smart people act foolishly, we must first understand how we came to define intelligence in this way, the abilities this definition captures, and some crucial aspects of thinking that it misses – skills that are equally essential for creativity and pragmatic problem solving, but which have been completely neglected in our education system. Only then can we begin to contemplate the origins of the intelligence trap – and the ways it might also be solved.

We shall see that many of these blind spots were apparent to contemporary researchers as Terman set about his tests, and they would become even more evident in the triumphs and failures of Beatrice, Shelley, Jess, Sara Ann, and the many other ‘Termites’, as their lives unfolded in sometimes dramatically unexpected ways. But thanks to the endurance of IQ, we are only just getting to grips with what this means and the implications for our decision making.

Indeed, the story of Terman’s own life reveals how a great intellect could backfire catastrophically, thanks to arrogance, prejudice – and love.

![]()

As with many great (if misguided) ideas, the germs of this understanding of intelligence emerged in the scientist’s childhood.

Terman grew up in rural Indiana in the early 1880s. Attending a ‘little red schoolhouse’, a single room with no books, the quiet, red-headed boy would sit and quietly observe his fellow pupils. Those who earned his scorn included a ‘backward’ albino child who would only play with his sister, and a ‘feeble-minded’ eighteen-year-old still struggling to grasp the alphabet. Another playmate, ‘an imaginative liar’, would go on to become an infamous serial killer, Terman later claimed – though he never said which one.11

Terman, however, knew he was different from the incurious children around him. He had been able to read before he entered that bookless schoolroom, and within the first term the teacher had allowed him to skip ahead and study third-grade lessons. His intellectual superiority was only confirmed when a travelling salesman visited the family farm. Finding a somewhat bookish household, he decided to pitch a volume on phrenology. To demonstrate the theories it contained, he sat with the Terman children around the fireside and began examining their scalps. The shape of the bone underneath, he explained, could reveal their virtues and vices. Something about the lumps and bumps beneath young Lewis’s thick ginger locks seemed to have particularly impressed him. This boy, he predicted, would achieve ‘great things’.

‘I think the prediction probably added a little to my self-confidence and caused me to strive for a more ambitious goal than I might otherwise have set’, Terman later wrote.12

By the time he was accepted for a prestigious position at Stanford University in 1910, Terman would long have known that phrenology was a pseudoscience; there was nothing in the lumps of his skull that could reflect his abilities. But he still had the strong suspicion that intelligence was some kind of innate characteristic that would mark out your path in life, and he had now found a new yardstick to measure the difference between the ‘feeble-minded’ and the ‘gifted’.

The object of Terman’s fascination was a test developed by Alfred Binet, a celebrated psychologist in fin de siècle Paris. In line with the French Republic’s principle of égalité among all citizens, the government had recently introduced compulsory education for all children between the ages of six and thirteen. Some children simply failed to respond to the opportunity, however, and the Ministry of Public Instruction faced a dilemma. Should these ‘imbeciles’ be educated separately within the school? Or should they be moved to asylums? Together with Théodore Simon, Binet invented a test that would help teachers to measure a child’s progress and adjust their education accordingly.13

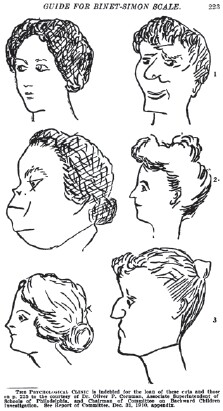

To a modern reader, some of the questions may seem rather absurd. As one test of vocabulary, Binet asked children to examine drawings of women’s faces and judge which was ‘prettier’ (see image below). But many of the tasks certainly did reflect crucial skills that would be essential for their success in later life. Binet would recite a string of numbers or words, for example, and the child had to recall them in the correct order to test their short-term memory. Another question would ask them to form a sentence with three given words – a test of their verbal prowess.

Binet himself was under no illusions that his test captured the full breadth of ‘intelligence’; he believed our ‘mental worth’ was simply too amorphous to be measured on a single scale and he baulked at the idea that a low score should come to define a child’s future opportunities, believing that it could be malleable across the lifetime.14 ‘We must protest and react against this brutal pessimism,’ he wrote; ‘we must try to show that it is founded on nothing.’15

But other psychologists, including Terman, were already embracing the concept of ‘general intelligence’ – the idea that there is some kind of mental ‘energy’ serving the brain, which can explain your performance in all kinds of problem solving and academic learning.16 If you are quicker at mental arithmetic, for instance, you are also more likely to be able to read well and to remember facts better. Terman believed that the IQ test would capture that raw brainpower, predetermined by our heredity, and that it could then predict your overall achievement in many different tasks throughout life.17

And so he set about revising an English-language version of Binet’s test, adding questions and expanding the exam for older children and adults, with questions such as:

If 2 pencils cost 5 cents, how many pencils can you buy for 50 cents?

And:

What is the difference between laziness and idleness?

Besides revising the questions, Terman also changed the way the result was expressed, using a simple formula that is still used today. Given that older children would do better than younger children, Terman first found the average score for each age. From these tables, you could assess a child’s ‘mental age’, which, when divided by their actual age and multiplied by 100, revealed their ‘intelligence quotient’. A ten-year-old thinking like a fifteen-year-old would have an IQ of 150; a ten-year-old thinking like a nine-year-old, in contrast, would have an IQ of 90. At all ages, the average would be 100.*

* For adults, who, at least according to the theory of general intelligence, have stopped developing intellectually, IQ is calculated slightly differently. Your score reflects not your ‘mental age’ but your position on the famous ‘bell curve’. An IQ of 145, for instance, suggests you are in the top 2 per cent of the population.

Many of Terman’s motives were noble: he wanted to offer an empirical foundation to the educational system so that teaching could be tailored to a child’s ability. But even at the test’s conception, there was an unsavoury streak in Terman’s thinking, as he envisaged a kind of social engineering based on the scores. Having profiled a small group of ‘hoboes’, for instance, he believed the IQ test could be used to separate delinquents from society, before they had even committed a crime.18 ‘Morality’, he wrote, ‘cannot flower and fruit if intelligence remains infantile.’19

Thankfully Terman never realised these plans, but his research caught the attention of the US Army during the First World War, and they used his tests to assess 1.75 million soldiers. The brightest were sent straight to officer training, while the weakest were dismissed from the army or consigned to a labour battalion. Many observers believed that the strategy greatly improved the recruitment process.

Carried by the wind of this success, Terman set about the project that would dominate the rest of his life: a vast survey of California’s most gifted pupils. Beginning in 1920, his team set about identifying the crème de la crème of California’s biggest cities. Teachers were encouraged to put forward their brightest pupils, and Terman’s assistants would then test their IQs, selecting only those children whose scores surpassed 140 (though they later lowered the threshold to 135). Assuming that intelligence was inherited, his team also tested these children’s siblings, allowing them to quickly establish a large cohort of more than a thousand gifted children in total – including Jess, Shelley, Beatrice and Sara Ann.

Over the next few decades, Terman’s team continued to follow the progress of these children, who affectionately referred to themselves as the ‘Termites’, and their stories would come to define the way we judge genius for almost a century. Termites who stood out include the nuclear physicist Norris Bradbury; Douglas McGlashan Kelley, who served as a prison psychiatrist in the Nuremberg trials; and the playwright Lilith James. By 1959, more than thirty had made it into Who’s Who in America, and nearly eighty were listed in American Men of Science.20

Not all the Termites achieved great academic success, but many shone in their respective careers nonetheless. Consider Shelley Smith – ‘the winsome child, loved by everyone’. After dropping out of Stanford University, she forged a career as a researcher and reporter at Life magazine, where she met and married the photographer Carl Mydans.21 Together they travelled around Europe and Asia reporting on political tensions in the build-up to the Second World War; she would later recall days running through foreign streets in a kind of reverie at the sights and sounds she was able to capture.22

Jess Oppenheimer, meanwhile – the ‘conceited, egocentric child’ with ‘no sense of humour’ – eventually became a writer for Fred Astaire’s radio show.23 Soon he was earning such vast sums that he found it hard not to giggle when he mentioned his own salary.24 His luck would only improve when he met the comedian Lucille Ball, and together they produced the hit TV show I Love Lucy. In between the scriptwriting, he tinkered with the technology of film-making, filing a patent for the teleprompter still used by news anchors today.

Those triumphs certainly bolster the idea of general intelligence; Terman’s tests may have only examined academic abilities, but they did indeed seem to reflect a kind of ‘raw’ underlying brainpower that helped these children to learn new ideas, solve problems and think creatively, allowing them to live fulfilled and successful lives regardless of the path they chose.

And Terman’s studies soon convinced other educators. In 1930, he had argued that ‘mental testing will develop to a lusty maturity within the next half century . . . within a few score years schoolchildren from the kindergarten to the university will be subjected to several times as many hours of testing as would now be thought reasonable’.25 He was right, and many new iterations of his test would follow in the subsequent decades.

Besides examining vocabulary and numerical reasoning, the later tests also included more sophisticated non-verbal conundrums, such as the quadrant on the following page.

The answer relies on you being able to think abstractly and see the common rule underlying the progression of shapes – which is surely reflective of some kind of advanced processing ability. Again, according to the idea of general intelligence, these kinds of abstract reasoning skills are meant to represent a kind of ‘raw brainpower’ – irrespective of your specific education – that underlies all our thinking.

Our education may teach us specialised knowledge in many different disciplines, but each subject ultimately relies on those more basic skills in abstract thinking.

What pattern completes this quadrant?

At the height of its popularity, most pupils in the US and the UK were sorted according to IQ. Today, the use of the test to screen young schoolchildren has fallen out of fashion, but its influence can still be felt throughout education and the workplace.

In the USA, for instance, the Scholastic Aptitude Test (SAT) used for college admissions was directly inspired by Terman’s work in the 1920s. The style of questioning may be different today, but such tests still capture the same basic abilities to remember facts, follow abstract rules, build a large vocabulary and spot patterns, leading some psychologists to describe them as IQ tests by proxy.

The same is true for many school and university entrance exams and employee recruitment tests – such as Graduate Record Examinations (GREs) and the Wonderlic Personnel Test used for selecting candidates in the workplace. It is a sign of Terman’s huge influence that even quarterbacks in the US National Football League take the Wonderlic test during recruitment, based on the theory that greater intelligence will improve the players’ strategic abilities on the field.

This is not just a Western phenomenon.26 Standardised tests, inspired by IQ, can be found in every corner of the globe and in some countries – most notably India, South Korea, Hong Kong, Singapore and Taiwan – a whole industry of ‘cram schools’ has grown up to coach students for exams like the GRE that are necessary to enter the most prestigious universities.27 (To give an idea of their importance, in India alone these cram schools are worth $6.4 billion annually.)

Just as important as the exams themselves, however, is the lingering influence of these theories on our attitudes. Even if you are sceptical of the IQ test, many people still believe that those abstract reasoning skills, so crucial for academic success, represent an underlying intelligence that automatically translates to better judgement and decision making across life – at work, at home, in finance or in politics. We assume that greater intelligence means that you are automatically better equipped to evaluate factual evidence before coming to a conclusion, for instance; it’s the reason we find the bizarre conspiracy theories of someone like Kary Mullis to be worthy of comment.

When we do pay lip service to other kinds of decision making that are not measured in intelligence tests, we tend to use fuzzy concepts like ‘life skills’ that are impossible to measure precisely, and we assume that they mostly come to us through osmosis, without deliberate training. Most of us certainly haven’t devoted the same time and effort to develop them as we did to abstract thinking and reasoning in education.

Since most academic tests are timed and require quick thinking, we have also been taught that the speed of our reasoning marks the quality of our minds; hesitation and indecision are undesirable, and any cognitive difficulty is a sign of our own failings. By and large, we respect people who think and act quickly, and to be ‘slow’ is simply a synonym for being stupid.

As we shall see in the following chapters, these are all misconceptions, and correcting them will be essential if we are to find ways out of the intelligence trap.

![]()

Before we examine the limits of the theory of general intelligence, and the thinking styles and abilities that it fails to capture, let’s be clear: most psychologists agree that these measures – be they IQ, SATs, GREs, or Wonderlic scores – do reflect something very important about the mind’s ability to learn and process complex information.

Unsurprisingly, given that they were developed precisely for this reason, these scores are best at predicting how well you do at school and university, but they are also modestly successful at predicting your career path after education. The capacity to juggle complex information will mean that you find complex mathematical or scientific concepts easier to understand and remember; that capacity to understand and remember difficult concepts might also help you to build a stronger argument in a history essay.

Particularly if you want to enter fields such as law, medicine or computer programming that will demand advanced learning and abstract reasoning, greater general intelligence is undoubtedly an advantage. Perhaps because of the socioeconomic success that comes with a white-collar career, people who score higher on intelligence tests tend to enjoy better health and live longer as a result, too.

Neuroscientists have also identified some of the anatomical differences that might account for greater general intelligence.28 The bark-like cerebral cortex is thicker and more wrinkled in more intelligent people, for example, and these also tend to have bigger brains overall.29 And the long-distance neural connections linking different brain regions (called ‘white matter’, since they are coated in a fatty sheath) appear to be wired differently too, forging more efficient networks for the transmission of signals.30 Together, these differences may contribute to faster processing and greater short-term and long-term memory capacity that should make it easier to see patterns and process complex information.

It would be foolish to deny the value of these results and the undoubtedly important role that intelligence plays in our lives. The problems come when we place too much faith in those measures’ capacity to represent someone’s total intellectual potential31 without recognising the variation in behaviour and performance that cannot be accounted for by these scores.32

If you consider surveys of lawyers, accountants or engineers, for instance, the average IQ may lie around 125 – showing that intelligence does give you an advantage. But the scores cover a considerable range, between around 95 (below average) and 157 (Termite territory).33 And when you compare the individuals’ success in those professions, those different scores can, at the very most, account for around 29 per cent of the variance in performance, as measured by managers’ ratings.34 That is certainly a very significant chunk, but even if you take into account factors such as motivation, it still leaves a vast range in performance that cannot be accounted for by their intelligence.35

For any career, there are plenty of people of lower IQ who outperform those with much higher scores, and people with greater intelligence who don’t make the most of their brainpower, confirming that qualities such as creativity or wise professional judgement just can’t be accounted for by that one number alone. ‘It’s a bit like being tall and playing basketball,’ David Perkins of the Harvard Graduate School of Education told me. If you don’t meet a very basic threshold, you won’t get far, but beyond that point other factors take over, he says.

Binet had warned us of this fact, and if you look closely at the data, this was apparent in the lives of the Termites. As a group, they were quite a bit more successful than the average American, but a vast number did not manage to fulfil their ambitions. The psychologist David Henry Feldman has examined the careers of the twenty-six brightest Termites, each of whom had a stratospheric IQ score of more than 180. Feldman was expecting to find each of these geniuses to have surpassed their peers, yet just four had reached a high level of professional distinction (becoming, for example, a judge or a highly honoured architect); as a group, they were only slightly more successful than those scoring 30?40 points fewer.36

Consider Beatrice and Sara Ann – the two precocious young girls with IQs of 192 whom we met at the start of this chapter. Beatrice dreamed of being a sculptor and writer, but ended up dabbling in real estate with her husband’s money – a stark contrast to the career of Oppenheimer, who had scored at the lower end of the group.37 Sara Ann, meanwhile, earned a PhD, but apparently found it hard to concentrate on her career; by her fifties she was living a semi-nomadic life, moving from friend’s house to friend’s house, and briefly, in a commune. ‘I think I was made, as a child, to be far too self-conscious of my status as a “Termite” . . . and given far too little to actually do with this mental endowment’, she later wrote.38

We can’t neglect the possibility that a few of the Termites may have made a conscious decision not to pursue a high-flying (and potentially stressful) career, but if general intelligence really were as important as Terman initially believed, you might have hoped for more of them to have reached great scientific, artistic or political success.39 ‘When we recall Terman’s early optimism about his subjects’ potential . . . there is the disappointing sense that they might have done more with their lives,’ Feldman concluded.

![]()

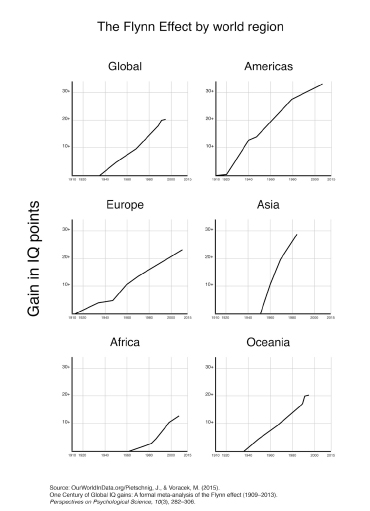

The interpretation of general intelligence as an all-powerful problem-solving-and-learning ability also has to contend with the Flynn Effect – a mysterious rise in IQ over the last few decades.

To find out more, I met Flynn at his son’s house in Oxford, during a flying visit from his home in New Zealand.40 Flynn is now a towering figure in intelligence research, but it was only meant to be a short distraction, he says: ‘I’m a moral philosopher who dabbles in psychology. And by dabbling I mean it’s taken over half my time for the past thirty years.’

Flynn’s interest in IQ began when he came across troubling claims that certain racial groups are inherently less intelligent. He suspected that environmental effects would explain the differences in IQ scores: richer and more educated families will have a bigger vocabulary, for instance, meaning that their children perform better in the verbal parts of the test.

As he analysed the various studies, however, he came across something even more puzzling: intelligence – for all races – appeared to have been rising over the decades. Psychologists had been slowly accounting for this by raising the bar of the exam – you had to answer more questions correctly to be given the same IQ score. But if you compare the raw data, the jump is remarkable, the equivalent of around thirty points over the last eighty years. ‘I thought, “Why aren’t psychologists dancing in the street over this? What the hell is going on?” ’ he told me.

Psychologists who believed that intelligence was largely inherited were dumbfounded. By comparing the IQ scores of siblings and strangers, they had estimated that genetics could explain around 70 per cent of the variation between different people. But genetic evolution is slow: our genes could not possibly have changed quickly enough to produce the great gains in IQ score that Flynn was observing.

Flynn instead argues that we need to consider the large changes in society. Even though we are not schooled in IQ tests explicitly, we have been taught to see patterns and think in symbols and categories from a young age. Just think of the elementary school lessons that lead us to consider the different branches of the tree of life, the different elements and the forces of nature. The more children are exposed to these ‘scientific spectacles’, the easier they find it to think in abstract terms more generally, Flynn suggests, leading to a steady rise in IQ over time. Our minds have been forged in Terman’s image.41

Other psychologists were sceptical at first. But the Flynn Effect has been documented across Europe, Asia, the Middle East and South America (see below) – anywhere undergoing industrialisation and Western-style educational reforms. The results suggest that general intelligence depends on the way our genes interact with the culture around us. Crucially – and in line with Flynn’s theory of ‘scientific spectacles’ – the scores in the different strands of the IQ test had not all risen equally. Non-verbal reasoning has improved much more than vocabulary or numerical reasoning, for instance – and other abilities that are not measured by IQ, like navigation, have actually deteriorated. We have simply refined a few specific skills that help us to think more abstractly. ‘Society makes highly different demands on us over time, and people have to respond.’ In this way, the Flynn Effect shows that we can’t just train one type of reasoning and assume that all the useful problem-solving abilities that we have come to associate with greater intelligence will follow suit, as some theories would have predicted.42

This should be obvious from everyday life. If the rise of IQ really reflected a profound improvement in overall thinking, then even the smartest eighty-year-old (such as Flynn) would seem like a dunce compared to the average millennial. Nor do we see a rise in patents, for example, which you would expect if the skills measured by general intelligence tests were critical for the kind of technological innovation that Jess Oppenheimer had specialised in;43 nor do we witness a preponderance of wise and rational political leaders, which you might expect if general intelligence alone was critical for truly insightful decision making. We do not live in the utopian future that Terman might have imagined, had he survived to see the Flynn Effect.44

![]()

Clearly, the skills measured by general intelligence tests are one important component of our mental machinery, governing how quickly we process and learn complex abstract information. But if we are to understand the full range of abilities in human decision making and problem solving, we need to expand our view to include many other elements – skills and styles of thinking that do not necessarily correlate strongly with IQ.

Attempts to define alternative forms of intelligence have often ended in disappointment, however. One popular buzzword has been ‘emotional intelligence’, for instance.* It certainly makes sense that social skills determine many of our life outcomes, though critics have argued that some of the popular tests of ‘EQ’ are flawed and fail to predict success better than IQ or measures of standard personality traits such as conscientiousness.45

* Despite these criticisms, updated theories of emotional intelligence do prove to be critical for our understanding of intuitive reasoning, and collective intelligence, as we will find out in Chapters 5 and 9.

In the 1980s, meanwhile, the psychologist Howard Gardner formulated a theory of ‘multiple intelligences’ that featured eight traits, including interpersonal and intrapersonal intelligence, bodily-kinaesthetic intelligence that makes you good at sport, and even ‘naturalistic intelligence’ – whether you are good at discerning different plants in the garden or even whether you can tell the brand of car from the sound of its engine. But many researchers consider that Gardner’s theory is too broad, without offering precise definitions and tests or any reliable evidence to support his conjectures, beyond the common-sense notion that some people do gravitate to some skills more than others.46 After all, we’ve always known that some people are better at sport and others excel at music, but does that make them separate intelligences? ‘Why not also talk about stuffing-beans-up-your-nose intelligence?’ Flynn said.

Robert Sternberg at Cornell University offers a middle ground with his Triarchic Theory of Successful Intelligence, which examines three particular types of intelligence – practical, analytical and creative – that can together influence decision making in a diverse range of cultures and situations.47

When I called him one afternoon, he apologised for the sound of his young children playing in the garden outside. But he soon forgot the noise as he described his frustration with education today and the outdated tools we use to calculate mental worth.

He compares the lack of progress in intelligence testing to the enormous leaps made in other fields, like medicine: it is as if doctors were still using outdated nineteenth-century drugs to treat life-threatening disease. ‘We’re at the level of using mercury to treat syphilis,’ he told me. ‘The SAT determines who gets into a good university, and then who gets into a good job – but all you get are good technicians with no common sense.’

Like Terman before him, Sternberg’s interest took root in childhood. Today, there is no questioning his brainpower: the American Psychological Association considered Sternberg the sixtieth most eminent psychologist in the twentieth century (twelve places above Terman).48 But as a second-grade child facing his first IQ test, his mind froze. When the results came in, it seemed clear to everyone – his teachers, his parents and Sternberg himself – that he was a dunce. That low score soon became a self-fulfilling prophecy, and Sternberg is certain he would have continued on this downward spiral, had it not been for his teacher in the fourth grade.49 ‘She thought there was more to a kid than an IQ score,’ he said. ‘My academic performance shot up just because she believed in me.’ It was only under her encouragement that his young mind began to flourish and blossom. Slippery concepts that had once slid from his grasp began to stick; he eventually became a first-class student.

As a freshman at Yale, he decided to take an introductory class in psychology to understand why he had been considered ‘so stupid’ as a child ? an interest that carried him to post-graduate research at Stanford, where he began to study developmental psychology. If IQ tests were so uninformative, he wondered, how could we better measure the skills that help people to succeed?

As luck would have it, observations of his own students started to provide the inspiration he needed. He remembers one girl, Alice, who had come to work in his lab. ‘Her test scores were terrific, she was a model student, but when she came in, she just didn’t have any creative ideas,’ he said. She was the complete opposite of another girl, Barbara, whose scores had been good but not ‘spectacular’, but who had been bursting with ideas to test in his lab.50 Another, Celia, had neither the amazing grades of Alice, nor the brilliant ideas of Barbara, but she was incredibly pragmatic – she thought of exceptional ways to plan and execute experiments, to build an efficient team and to get her papers published.

Inspired by Alice, Barbara and Celia, Sternberg began to formulate a theory of human intelligence, which he defined as ‘the ability to achieve success in life, according to one’s personal standards, within one’s sociocultural context’. Avoiding the (perhaps overly) broad definitions of Gardner’s multiple intelligences, he confined his theory to those three abilities – analytical, creative and practical – and considered how they might be defined, tested and nurtured.

Analytical intelligence is essentially the kind of thinking that Terman was studying; it includes the abilities that allowed Alice to perform so well on her SATs. Creative intelligence, in contrast, examines our abilities ‘to invent, imagine and suppose’, as Sternberg puts it. While schools and universities already encourage this kind of thinking in creative writing classes, Sternberg points out that subjects such as history, science and foreign languages can also incorporate exercises designed to measure and train creativity. A student looking at European history, for instance, might be asked, ‘Would the First World War have occurred, had Franz Ferdinand never been shot?’ or, ‘What would the world look like today, if Germany had won the Second World War?’ In a science lesson on animal vision, it might involve imagining a scene from the eyes of a bee. ‘Describe what a bee can see, that you cannot.’51

Responding to these questions, students would still have a chance to show off their factual knowledge, but they are also being forced to exercise counter-factual thinking, to imagine events that have never happened – skills that are clearly useful in many creative professions. Jess Oppenheimer exercised this kind of thinking in his scriptwriting and also his technical direction.

Practical intelligence, meanwhile, concerns a different kind of innovation: the ability to plan and execute an idea, and to overcome life’s messy, ill-defined problems in the most pragmatic way possible. It includes traits like ‘metacognition’ – whether you can judge your strengths and your weaknesses and work out the best ways to overcome them, and the unspoken, tacit knowledge that comes from experience and allows you to solve problems on the fly. It also includes some of the skills that others have called emotional or social intelligence – the ability to read motives and to persuade others to do what you want. Among the Termites, Shelley Smith Mydans’ quick thinking as a war reporter, and her ability to navigate her escape from a Japanese prison camp, may best personify this kind of intelligence.

Of the three styles of thinking, practical intelligence may be the hardest to test or teach explicitly, but Sternberg suggests there are ways to cultivate it at school and university. In a business studies course, this may involve rating different strategies to deal with a personnel shortage;52 in a history lesson on slavery, you might ask a student to consider the challenges of implementing the underground railroad for escaped slaves.53 Whatever the subject, the core idea is to demand that students think of pragmatic solutions to an issue they may not have encountered before.

Crucially, Sternberg has since managed to test his theories in many diverse situations. At Yale University, for example, he helped set up a psychology summer programme aimed at gifted high-school students. The children were tested according to his different measures of intelligence, and then divided randomly into groups and taught according to the principles of a particular kind of intelligence. After a morning studying the psychology of depression, for instance, some were asked to formulate their own theories based on what they had learnt – a task to train creative intelligence; others were asked how they might apply that knowledge to help a friend who was suffering from mental illness – a task to encourage practical thinking. ‘The idea was that some kids will be capitalising on their strengths, and others will be correcting their weaknesses,’ Sternberg told me.

The results were encouraging. They showed that teaching the children according to their particular type of intelligence improved their overall scores in a final exam – suggesting that education in general should help cater for people with a more creative or practical style of thinking. Moreover, Sternberg found that the practical and creative intelligence tests had managed to identify a far greater range of students from different ethnic and economic backgrounds – a refreshing diversity that was apparent as soon as they arrived for the course, Sternberg said.

In a later study, Sternberg recruited 110 schools (with more than 7,700 students in total) to apply the same principles to the teaching of mathematics, science and English language. Again, the results were unequivocal – the children taught to develop their practical and creative intelligence showed greater gains overall, and even performed better on analytical, memory-based questions – suggesting that the more rounded approach had generally helped them to absorb and engage with the material.

Perhaps most convincingly, Sternberg’s Rainbow Project collaborated with the admissions departments of various universities – including Yale, Brigham Young and the University of California Irvine – to build an alternative entrance exam that combines traditional SAT scores with measures of practical and creative intelligence. He found that the new test was roughly twice as accurate at predicting the students’ GPA (grade point average) scores in their first year at university, compared to their SAT scores alone, which suggests that it does indeed capture different ways of thinking and reasoning that are valuable for success in advanced education.54

Away from academia, Sternberg has also developed tests of practical intelligence for business, and trialled them in executives and salespeople across industries, from local estate agents to Fortune 500 companies. One question asked the participants to rank potential approaches to different situations, such as how to deal with a perfectionist colleague whose slow progress may prevent your group from meeting its target, using various nudge techniques. Another scenario got them to explain how they would change their sales strategy when stocks are running low.

In each case, the questions test people’s ability to prioritise tasks and weigh up the value of different options, to recognise the consequences of their actions and pre-empt potential challenges, and to persuade colleagues of pragmatic compromises that are necessary to keep a project moving without a stalemate. Crucially, Sternberg has found that these tests predicted measures of success such as yearly profits, the chances of winning a professional award, and overall job satisfaction.

In the military, meanwhile, Sternberg examined various measures of leadership performance among platoon commanders, company commanders and battalion commanders. They were asked how to deal with soldier insubordination, for instance – or the best way to communicate the goals of a mission. Again, practical intelligence – and tacit knowledge, in particular – predicted their leadership ability better than traditional measures of general intelligence.55

Sternberg’s measures may lack the elegance of a one-size-fits-all IQ score, but they are a step closer to measuring the kind of thinking that allowed Jess Oppenheimer and Shelley Smith Mydans to succeed where other Termites failed.56 ‘Sternberg’s on the right track,’ Flynn told me. ‘He was excellent in terms of showing that it was possible to measure more than analytic skills.’

Disappointingly, acceptance has been slow. Although his measures have been adopted at Tufts University and Oklahoma State University, they are still not widespread. ‘People may say things will change, but then things go back to the way they were before,’ Sternberg said. Just like when he was a boy, teachers are still too quick to judge a child’s potential based on narrow, abstract tests – a fact he has witnessed in the education of his own children, one of whom is now a successful Silicon Valley entrepreneur. ‘I have five kids and all of them at one time or another have been diagnosed as potential losers,’ he said, ‘and they’ve done fine.’

![]()

While Sternberg’s research may not have revolutionised education in the way he had hoped, it has inspired other researchers to build on his concept of tacit knowledge – including some intriguing new research on the concept of ‘cultural intelligence’.

Soon Ang, a professor of management at the Nanyang Technological University in Singapore, has pioneered much of this work. In the late 1990s, she was acting as a consultant to several multinational companies who asked her to pull together team of programmers, from many different countries, to help them cope with the ‘Y2K bug’.

The programmers were undeniably intelligent and experienced, but Ang observed that they were disappointingly ineffective at working together: she found that Indian and Filipino programmers would appear to agree on a solution to a problem, for instance, only for the members to then implement it in different and incompatible ways. Although the team members were all speaking the same language, Ang realised that they were struggling to bridge the cultural divide and comprehend the different ways of working.

Inspired, in part, by Robert Sternberg’s work, she developed a measure of ‘cultural intelligence’ (CQ) that examines your general sensitivity to different cultural norms. As one simple example: a Brit or American may be surprised to present an idea to Japanese colleagues, only to be met with silence. Someone with low cultural intelligence may interpret the reaction as a sign of disinterest; someone with high cultural intelligence would realise that, in Japan, you may need to explicitly ask for feedback before getting a response – even if the reaction is positive. Or consider the role of small talk in building a relationship. In some European countries, it’s much better to move directly to the matter at hand, but in India it is important to take the time to build relationships – and someone with high cultural intelligence would recognise that fact.

Ang found that some people are consistently better at interpreting those signs than others. Importantly, the measures of cultural intelligence test not only your knowledge of a specific culture, but also your general sensitivity to the potential areas of misunderstanding in unfamiliar countries, and how well you would adapt to them. And like Sternberg’s measures of practical intelligence, these tacit skills don’t correlate very strongly with IQ or other tests of academic potential – reaffirming the idea that they are measuring different things. As Ang’s programmers had shown, you could have high general intelligence but low cultural intelligence.

‘CQ’ has now been linked to many measures of success. It can predict how quickly expats will adapt to their new life, the performance of international salespeople, and participants’ abilities to negotiate.57 Beyond business, cultural intelligence may also determine the experiences of students studying abroad, charity workers in disaster zones, and teachers at international schools – or even your simple enjoyment of a holiday abroad.

![]()

My conversations with Flynn and Sternberg were humbling. Despite having performed well academically, I have to admit that I lack many of the other skills that Sternberg’s tests have been measuring, including many forms of tacit knowledge that may be obvious to some people.

Imagine, for instance, that your boss is a micromanager and wants to have the last say on every project – a problem many of us will have encountered. Having spoken to Sternberg, I realised that someone with practical intelligence might skilfully massage the micromanager’s sense of self-importance by suggesting two solutions to a problem: the preferred answer, and a decoy they could reject while feeling they have still left their mark on the project. It’s a strategy that had never once occurred to me.

Or consider you are a teacher, and you find a group of children squabbling in the playground. Do you scold them, or do you come up with a simple distraction that will cause them to forget their quarrel? To my friend Emma, who teaches in a primary school in Oxford, the latter is second nature; her mind is full of games and subtle hints to nudge their behaviour. But when I tried to help her out in the classroom one day, I was clueless, and the children were soon running rings around me.

I’m not unusual in this. In Sternberg’s tests of practical intelligence, a surprising number of people lacked this pragmatic judgement, even if, like me, they score higher than average on other measures of intelligence, and even if they had years of experience in the job at hand. The studies do not agree on the exact relation, though. At best, the measures of tacit knowledge are very modestly linked to IQ scores; at worst, they are negatively correlated. Some people just seem to find it easier to implicitly learn the rules of pragmatic problem solving – and that ability is not very closely related to general intelligence.

For our purposes, it’s also worth paying special attention to counter-factual thinking – an element of creative intelligence that allows us to think of the alternative outcomes of an event or to momentarily imagine ourselves in a different situation. It’s the capacity to ask ‘what if . . .?’ and without it, you may find yourself helpless when faced with an unexpected challenge. Without being able to reappraise your past, you’ll also struggle to learn from your mistakes to find better solutions in the future. Again, that’s neglected on most academic tests.

In this way, Sternberg’s theories help us to understand the frustrations of intelligent people who somehow struggle with some of the basic tasks of working life – such as planning projects, imagining the consequences of their actions and pre-empting problems before they emerge. Failed entrepreneurs may be one example: around nine out of ten new business ventures fail, often because the innovator has found a good idea but lacks the capacity to deal with the challenges of implementing it.

If we consider that SATs or IQ tests reflect a unitary, underlying mental energy – a ‘raw brainpower’ – that governs all kinds of problem solving, this behaviour doesn’t make much sense; people of high general intelligence should have picked up those skills. Sternberg’s theory allows us to disentangle those other components and then define and measure them with scientific rigour, showing that they are largely independent abilities.

These are important first steps in helping us to understand why apparently clever people may lack the good judgement that we might have expected given their academic credentials. This is just the start, however. In the next chapters we will discover many other essential thinking styles and cognitive skills that had been neglected by psychologists – and the reasons that greater intelligence, rather than protecting us from error, can sometimes drive us to make even bigger mistakes. Sternberg’s theories only begin to scratch the surface.

![]()

In hindsight, Lewis Terman’s own life exemplifies many of these findings. From early childhood he had always excelled academically, rising from his humble background to become president of the American Psychological Association. Nor should we forget the fact that he masterminded one of the first and most ambitious cohort studies ever conducted, collecting reams of data that scientists continued to study four decades after his death. He was clearly a highly innovative man.

And yet it is now so easy to find glaring flaws in his thinking. A good scientist should leave no stone uncovered before reaching a conclusion – but Terman turned a blind eye to data that might have contradicted his own preconceptions. He was so sure of the genetic nature of intelligence that he neglected to hunt for talented children in poorer neighbourhoods. And he must have known that meddling in his subjects’ lives would skew the results, but he often offered financial support and professional recommendations to his Termites, boosting their chances of success. He was neglecting the most basic (tacit) knowledge of the scientific method, which even the most inexperienced undergraduate should take for granted.

This is not to mention his troubling political leanings. Terman’s interest in social engineering led him to join the Human Betterment Foundation – a group that called for the compulsory sterilisation of those showing undesirable qualities.58 Moreover, when reading Terman’s early papers, it is shocking how easily he dismissed the intellectual potential of African Americans and Hispanics, based on a mere handful of case-studies. Describing the poor scores of just two Portuguese boys, he wrote: ‘Their dullness seems to be racial, or at least inherent in the family stocks from which they came.’59 Further research, he was sure, would reveal ‘enormously significant racial differences in general intelligence’.

Perhaps it is unfair to judge the man by today’s standards; certainly, some psychologists believe that we should be kind to Terman’s faults, product as he was of a different time. Except that we know Terman had been exposed to other points of view; he must have read Binet’s concerns about the misuse of his intelligence test.

A wiser man might have explored these criticisms, but when Terman was challenged on these points, he responded with knee-jerk vitriol rather than reasoned argument. In 1922, the journalist and political commentator Walter Lippmann wrote an article in the New Republic, questioning the IQ test’s reliability. ‘It is not possible’, Lippmann wrote, ‘to imagine a more contemptible proceeding than to confront a child with a set of puzzles, and after an hour’s monkeying with them, proclaim to the child, or to his parents, that here is a C-individual.’60

Lippmann’s scepticism was entirely understandable, yet Terman’s response was an ad hominem attack: ‘Now it is evident that Mr Lippmann has been seeing red; also, that seeing red is not very conducive to seeing clearly’, he wrote in response. ‘Clearly, something has hit the bulls-eye of one of Mr Lippmann’s emotional complexes.’61

Even the Termites had started to question the values of their test results by the ends of their lives. Sara Ann – the charming little girl with an IQ of 192, who had ‘bribed’ her experimenters with a gumdrop – certainly resented the fact that she had not cultivated other cognitive skills that had not been measured in her test. ‘My great regret is that my left-brain parents, spurred on by my Terman group experience, pretty completely bypassed any encouragement of whatever creative talent I may have had’, she wrote. ‘I now see the latter area as of greater significance, and intelligence as its hand-maiden. [I’m] sorry I didn’t become aware of this fifty years ago.’62

Terman’s views softened slightly over the years, and he would later admit that ‘intellect and achievement are far from perfectly correlated’, yet his test scores continued to dominate his opinions of the people around him; they even cast a shadow over his relationships with his family. According to Terman’s biographer, Henry Minton, each of his children and grandchildren had taken the IQ test, and his love for them appeared to vary according to the results. His letters were full of pride for his son, Fred, a talented engineer and an early pioneer in Silicon Valley; his daughter, Helen, barely merited a mention.

Perhaps most telling are his granddaughter Doris’s recollections of family dinners, during which the place settings were arranged in order of intelligence: Fred sat at the head of the table next to Lewis; Helen and her daughter Doris sat at the other end, where they could help the maid.63 Each family member placed according to a test they had taken years before – a tiny glimpse, perhaps, of the way Terman would have liked to arrange us all.