6

A bullshit detection kit: How to recognise lies and misinformation

If you were online at the turn of the new millennium, you may remember reading about the myth of the ‘flesh-eating bananas’.

In late 1999, a chain email began to spread across the internet, reporting that fruit imported from Central America could infect people with ‘necrotising fasciitis’ – a rare disease in which the skin erupts into livid purple boils before disintegrating and peeling away from muscle and bone. The email stated that:

Recently this disease has decimated the monkey population in Costa Rica . . . It is advised not to purchase bananas for the next three weeks as this is the period of time for which bananas that have been shipped to the US with the possibility of carrying this disease. If you have eaten a banana in the last 2–3 days and come down with a fever followed by a skin infection seek MEDICAL ATTENTION!!!

The skin infection from necrotizing fasciitis is very painful and eats two to three centimeters of flesh per hour. Amputation is likely, death is possible. If you are more than an hour from a medical center burning the flesh ahead of the infected area is advised to help slow the spread of the infection. The FDA has been reluctant to issue a country wide warning because of fear of a nationwide panic. They have secretly admitted that they feel upwards of 15,000 Americans will be affected by this but that these are ‘acceptable numbers’. Please forward this to as many of the people you care about as possible as we do not feel 15,000 people is an acceptable number.

By 28 January 2000, public concern was great enough for the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to issue a statement denying the risks. But their response only poured fuel on the flames, as people forgot the correction but remembered the scary, vivid idea of the flesh-eating bananas. Some of the chain emails even started citing the CDC as the source of the rumours, giving them greater credibility.

Within weeks, the CDC was hearing from so many distressed callers that it was forced to set up a banana hotline, and it was only by the end of the year that the panic burned itself out as the feared epidemic failed to materialise.1

![]()

The necrotising-fasciitis emails may have been one of the first internet memes – but misinformation is not a new phenomenon. As the eighteenth-century writer Jonathan Swift wrote in an essay on the rapid spread of political lies: ‘Falsehood flies and the truth comes limping after it’.

Today, so-called ‘fake news’ is more prevalent than ever. One survey in 2016 found that more than 50 per cent of the most shared medical stories on Facebook had been debunked by doctors, including the claim that ‘dandelion weed can boost your immune system and cure cancer’ and reports that the HPV vaccine increased your risk of developing cancer.2

The phenomenon is by no means restricted to the West – though the particular medium may depend on the country. In India, for instance, false rumours spread like wildfire through WhatsApp across its 300 million smartphones – covering everything from local salt shortages to political propaganda and wrongful allegations of mass kidnappings. In 2018, these rumours even triggered a spate of lynchings.3

You would hope that traditional education could protect us from these lies. As the great American philosopher John Dewey wrote in the early twentieth century: ‘If our schools turn out their pupils in that attitude of mind which is conducive to good judgment in any department of affairs in which the pupils are placed, they have done more than if they sent out their pupils merely possessed of vast stores of information, or high degrees of skill in specialized branches.’4

Unfortunately, the work on dysrationalia shows us this is far from being the case. While university graduates are less likely than average to believe in political conspiracy theories, they are slightly more susceptible to misinformation about medicine, believing that pharmaceutical companies are withholding cancer drugs for profit or that doctors are hiding the fact that vaccines cause illnesses, for instance.5 They are also more likely to use unproven, complementary medicines.6

It is telling that one of the first people to introduce the flesh-eating banana scare to Canada was Arlette Mendicino, who worked at the University of Ottawa’s medical faculty ? someone who should have been more sceptical.7 ‘I thought about my family, I thought about my friends. I had good intentions,’ she told CBC News after she found out she’d been fooled. Within a few days, the message had spread across the country.

In our initial discussion of the intelligence trap, we explored the reasons why having a higher IQ might make you ignore contradictory information, so that you are even more tenacious in your existing beliefs, but this didn’t really explain why someone like Mendicino could be so gullible in the first place. Clearly this involves yet more reasoning skills that aren’t included in the traditional definitions of general intelligence, but that are essential if we want to become immune to these kinds of lies and rumours.

The good news is that certain critical thinking techniques can protect us from being duped, but to learn how to apply them, we first need to understand how certain forms of misinformation are deliberately designed to escape deliberation and why the traditional attempts to correct them often backfire so spectacularly. This new understanding not only teaches us how to avoid being duped ourselves; it is also changing the way that many global organisations respond to unfounded rumours.

![]()

Before we continue, first consider the following statements and say which is true and which is false in each pairing:

Bees cannot remember left from right

And

![]()

Cracking your knuckles can cause arthritis

And now consider the following opinions, and say which rings true for you:

Woes unite foes

Strife bonds enemies

And consider which of these online sellers you would shop with:

rifo073 Average user rating: 3.2

edlokaq8 Average user rating: 3.6

We’ll explore your responses in a few pages, but reading the pairs of statements you might have had a hunch that one was truthful or more trustworthy than the other. And the reasons why are helping scientists to understand the concept of ‘truthiness’.

The term was first popularised by the American comedian Stephen Colbert in 2005 to describe the ‘truth that comes from the gut, not from the book’ as a reaction to George W. Bush’s decision making and the public perception of his thinking. But it soon became clear that the concept could be applied to many situations8 and it has now sparked serious scientific research.

Norbert Schwarz and Eryn Newman have led much of this work, and to find out more, I visited them in their lab at the University of Southern California in Los Angeles. Schwarz happens to have been one of the leaders in the new science of emotional decision making that we touched on in the last chapter, showing, for instance, the way the weather sways our judgement of apparently objective choices. The work on truthiness extends this idea to examine how we intuitively judge the merits of new information.

According to Schwarz and Newman, truthiness comes from two particular feelings: familiarity (whether we feel that we have heard something like it before) and fluency (how easy a statement is to process). Importantly, most people are not even aware that these two subtle feelings are influencing their judgement – yet they can nevertheless move us to believe a statement without questioning its underlying premises or noting its logical inconsistencies.

As a simple example, consider the following question from some of Schwarz’s earlier studies of the subject:

How many animals of each kind did Moses take on the Ark?

The correct answer is, of course, zero. Moses didn’t have an ark ? it was Noah who weathered the flood. Yet even when assessing highly intelligent students at a top university, Schwarz has found that just 12 per cent of people register that fact.9

The problem is that the question’s phrasing fits into our basic conceptual understanding of the Bible, meaning we are distracted by the red herring – the quantity of animals – rather than focusing on the name of the person involved. ‘It’s some old guy who had something to do with the Bible, so the whole gist is OK,’ Schwarz told me. The question turns us into a cognitive miser, in other words – and even the smart university students in Schwarz’s study didn’t notice the fallacy.

Like many of the feelings fuelling our intuitions, fluency and familiarity can be accurate signals. It would be too exhausting to examine everything in extreme detail, particularly if it’s old news; and if we’ve heard something a few times, that would suggest that it’s a consensus opinion, which may be more likely to be true. Furthermore, things that seem superficially straightforward often are exactly that; there’s no hidden motive. So it makes sense to trust things that feel fluent.

What’s shocking is just how easy it is to manipulate these two cues with simple changes to presentation so that we miss crucial details.

In one iconic experiment, Schwarz found that people are more likely to fall for the Moses illusion if that statement is written in a pleasant, easy-to-read font – making the reading more fluent – compared to an uglier, italic script that is harder to process. For similar reasons, we are also more likely to believe people talking in a recognisable accent, compared to someone whose speech is harder to understand, and we place our trust in online vendors with easier-to-pronounce names, irrespective of their individual ratings and reviews by other members. Even a simple rhyme can boost the ‘truthiness’ of a statement, since the resonating sounds of the words makes it easier for the brain to process.10

Were you influenced by any of these factors in those questions at the start of this chapter? For the record, bees really can be trained to distinguish Impressionist and Cubist painters (and they do also seem to distinguish left from right); coffee can reduce your risk of diabetes, while cracking your knuckles does not appear to cause arthritis.11 But if you are like most people, you may have been swayed by the subtle differences in the way the statements were presented – with the fainter, grey ink and ugly fonts making the true statements harder to read, and less “truthy” as a result. And although they mean exactly the same thing, you are more likely to endorse ‘woes unite foes’ than ‘strife bonds enemies’ – simply because it rhymes.

Sometimes, increasing a statement’s truthiness can be as simple as adding an irrelevant picture. In one rather macabre experiment from 2012, Newman showed her participants statements about a series of famous figures – such as a sentence claiming that the indie singer Nick Cave was dead.12 When the statement was accompanied by a stock photo of the singer, they were more likely to believe that the statement was true, compared to the participants who saw only the plain text.

The photo of Nick Cave could, of course, have been taken at any point in his life. ‘It makes no sense that someone would use it as evidence – it just shows you that he’s a musician in a random band,’ Newman told me. ‘But from a psychological perspective it made sense. Anything that would make it easy to picture or easy to imagine something should sway someone’s judgement.’ Newman has also tested the principle on a range of general knowledge statements; they were more likely to agree that ‘magnesium is the liquid metal inside a thermometer’ or ‘giraffes are the only mammal that cannot jump’ if the statement was accompanied by a picture of the thermometer or giraffe. Once again, the photos added no further evidence, but significantly increased the participants’ acceptance of the statement.

Interestingly, detailed verbal descriptions (such as of the celebrities’ physical characteristics) provided similar benefits. If we are concerned about whether he is alive or dead, it shouldn’t matter if we hear that Nick Cave is a white, male singer – but those small, irrelevant details really do make a statement more persuasive.

Perhaps the most powerful strategy to boost a statement’s truthiness is simple repetition. In one study, Schwarz’s colleagues handed out a list of statements that were said to come from members of the ‘National Alliance Party of Belgium’ (a fictitious group invented for the experiment). But in some of the documents, there appeared to be a glitch in the printing, meaning the same statement from the same person appeared three times. Despite the fact that it was clearly providing no new information, the participants reading the repeated statement were subsequently more likely to believe that it reflected the consensus of the whole group.

Schwarz observed the same effect when his participants read notes about a focus group discussing steps to protect a local park. Some participants read quotes from the same particularly mouthy person who made the same point three times; others read a document in which three different people made the same point, or a document in which three people presented separate arguments. As you might expect, the participants were more likely to be swayed by an argument if they heard it from different people all converging on the same idea. But they were almost as convinced by the argument when it came from a single person, multiple times.13 ‘It made hardly any difference,’ Schwarz said. ‘You are not tracking who said what.’

To make matters worse, the more we see someone, the more familiar they become, and this makes them appear to be more trustworthy.14 A liar can become an ‘expert’; a lone voice begins to sound like a chorus, just through repeated exposure.

These strategies have long been known to professional purveyors of misinformation. ‘The most brilliant propagandist technique will yield no success unless one fundamental principle is borne in mind constantly and with unflagging attention,’ Adolf Hitler noted in Mein Kampf. ‘It must confine itself to a few points and repeat them over and over.’

And they are no less prevalent today. The manufacturers of a quack medicine or a fad diet, for instance, will dress up their claims with reassuringly technical diagrams that add little to their argument – with powerful effect. Indeed, one study found that the mere presence of a brain scan can make pseudo-scientific claims seem more credible – even if the photo is meaningless to the average reader.15

The power of repetition, meanwhile, allows a small but vocal minority to persuade the public that their opinion is more popular than it really is. This tactic was regularly employed by tobacco industry lobbyists in the 1960s and 70s. The vice president of the Tobacco Institute, Fred Panzer, admitted as much in an internal memo, describing the industry’s ‘brilliantly conceived strategy’ to create ‘doubt about the health charge without actually denying it’, by recruiting scientists to regularly question overwhelming medical opinion.16

The same strategies will almost certainly have been at play for many other myths. It is extremely common for media outlets to feature prominent climate change deniers (such as Nigel Lawson in the UK) who have no background in the science but who regularly question the link between human activity and rising sea temperatures. With repetition, their message begins to sound more trustworthy – even though it is only the same small minority repeating the same message. Similarly, you may not remember when you first heard that mobile phones cause cancer and vaccines cause autism, and it’s quite possible that you may have even been highly doubtful when you did. But each time you read the headline, the claim gained truthiness, and you became a little less sceptical.

To make matters worse, attempts to debunk these claims often backfire, accidentally spreading the myth. In one experiment, Schwarz showed some undergraduate students a leaflet from the US Centers for Disease Control, which aimed to debunk some of the myths around vaccinations – such as the commonly held idea that we may become ill after getting the flu shot. Within just thirty minutes, the participants had already started to remember 15 per cent of the false claims as facts, and when asked about their intentions to act on the information, they reported that they were less likely to be immunised as a result.17

The problem is that the boring details of the correction were quickly forgotten, while the false claims lingered for longer, and became more familiar as a result. By repeating the claim – even to debunk it – you are inadvertently boosting its truthiness. ‘You’re literally turning warnings into recommendations,’ Schwarz told me.

The CDC observed exactly this when they tried to put the banana hoax to rest. It’s little wonder. Their headline: ‘False Internet report about necrotizing fasciitis associated with bananas’ was far less digestible – or ‘cognitively fluent’, in the technical terms – than the vivid (and terrifying) idea of a flesh-eating virus and a government cover-up.

In line with the work on motivated reasoning, our broader worldviews will almost certainly determine how susceptible we are to misinformation – partly because a message that already fits with our existing opinions is processed more fluently and feels more familiar. This may help to explain why more educated people seem particularly susceptible to medical misinformation: it seems that fears about healthcare, in general, are more common among wealthier, more middle-class people, who may also be more likely to have degrees. Conspiracies about doctors – and beliefs in alternative medicine – may naturally fit into that belief system.

The same processes may also explain why politicians’ lies continue to spread long after they have been corrected – including Donald Trump’s theory that Barack Obama was not born in the United States. As you might expect from the research on motivated reasoning, this was particularly believed by Republicans – but even 14 per cent of Democrats held the view as late as 2017.18

We can also see this mental inertia in the lingering messages of certain advertising campaigns. Consider the marketing of the mouthwash Listerine. For decades, Listerine’s adverts falsely claimed that the mouthwash could soothe sore throats and protect consumers from the common cold. But after a long legal battle in the late 1970s, the Federal Trade Commission forced the company to run adverts correcting the myths. Despite a sixteen-month, $10-million-dollar campaign retracting the statements, the adverts were only marginally effective.19

![]()

This new understanding of misinformation has been the cause for serious soul searching in organisations that are attempting to spread the truth.

In an influential white paper, John Cook, then at the University of Queensland, and Stephan Lewandowsky, then at the University of Western Australia, pointed out that most organisations had operated on the ‘information deficit model’ – assuming that misperceptions come from a lack of knowledge.20 To counter misinformation on topics such as vaccination, you simply offer the facts and try to make sure that as many people see them as possible.

Our understanding of the intelligence trap shows us that this isn’t enough: we simply can’t assume that smart, educated people will absorb the facts we are giving them. As Cook and Lewandowsky put it: ‘It’s not just what people think that matters, but how they think.’

Their ‘debunking handbook’ offers some solutions. For one thing, organisations hoping to combat misinformation should ditch the ‘myth-busting’ approach where they emphasise the misconception and then explain the facts. A cursory glance at an NHS webpage on vaccines, for instance, lists the ten myths, in bold, right at the top of the page.21 They are then repeated again, as bold headlines, underneath. According to the latest cognitive science, this kind of approach places too much emphasis on the misinformation itself: the presentation means it is processed more fluently than the facts, and the multiple repetitions simply increase its familiarity. As we have seen, those two feelings – of cognitive fluency and familiarity – contribute to the sense of truthiness, meaning that an anti-vaccination campaigner could hardly have done a better job in reinforcing the view.

Instead, Cook and Lewandowsky argue that any attempt to debunk a misconception should be careful to design the page so that the fact stands out. If possible, you should avoid repeating the myth entirely. When trying to combat fears about vaccines, for instance, you may just decide to focus on the scientifically proven, positive benefits. But if it is necessary to discuss the myths, you can at least make sure that the false statements are less salient than the truth you are trying to convey. It’s better to headline your article ‘Flu vaccines are safe and effective’ than ‘Myth: Vaccines can give you the flu’.

Cook and Lewandowsky also point out that many organisations may be too earnest in their presentation of the facts – to the point that they over-complicate the argument, again reducing the fluency of the message. Instead, they argue that it is best to be selective in the evidence you present: sometimes two facts are more powerful than ten.

For more controversial topics, it is also possible to reduce people’s motivated reasoning in the way you frame the issue. If you are trying to discuss the need for companies to pay for the fossil fuels they consume, for example, you are more likely to win over conservative voters by calling it a ‘carbon offset’ rather than a ‘tax’, which is a more loaded term and triggers their political identity.

Although my own browse of various public health websites suggests that many institutions still have a long way to go, there are some signs of movement. In 2017, the World Health Organisation announced that they had now adopted these guidelines to deal with the misinformation spread by ‘anti-vaccination’ campaigners.22

![]()

But how can we protect ourselves?

To answer that question, we need to explore another form of metacognition called ‘cognitive reflection’, which, although related to the forms of reflection we examined in the previous chapter, more specifically concerns the ways we respond to factual information, rather than emotional self-awareness.

Cognitive reflection can be measured with a simple test of just three questions, and you can get a flavour of what it involves by considering the following example:

The maths required is not beyond the most elementary education, but the majority of people – even students at Ivy League colleges – only answer between one and two of the three questions correctly.23 That’s because they are designed with misleadingly obvious, but incorrect, answers (in this case, $0.10, 24 days, and 100 minutes). It is only once you challenge those assumptions that you can then come to the correct answer ($0.05, 47 days, and 5 minutes).

This makes it very different from the IQ questions we examined in Chapter 1, which may involve complex calculations, but which do not ask you to question an enticing but incorrect lure. In this way, the Cognitive Reflection Test offers a short and sweet way of measuring how we appraise information and our abilities to override the misleading cues you may face in real life, where problems are ill-defined and messages deceptive.24

As you might expect, people who score better on the test are less likely to suffer from various cognitive biases – and sure enough scores on the CRT predict how well people perform on Keith Stanovich’s rationality quotient.

In the early 2010s, however, a PhD student called Gordon Pennycook (then at the University of Waterloo) began to explore whether cognitive reflection could also influence our broader beliefs. Someone who stops to challenge their intuitions, and think of alternative possibilities, should be less likely to take evidence at face value, he suspected – making them less vulnerable to misinformation. Sure enough, Pennycook found that people with this more analytical thinking style are less likely to endorse magical thinking and complementary medicine. Further studies have shown that they are also more likely to reject the theory of evolution and to believe 9/11 conspiracy theories.

Crucially, this holds even when you control for other potential factors – like intelligence or education – underlining the fact that it’s not just your brainpower that really matters; it’s whether or not you use it.25 ‘We should distinguish between cognitive ability and cognitive style,’ Pennycook told me. Or, to put it more bluntly: ‘If you aren’t willing to think, you aren’t, practically speaking, intelligent.’ As we have seen with other measures of thinking and reasoning, we are often fairly bad at guessing where we lie on that spectrum. ‘People that are actually low in analytic [reflective] thinking believe they are fairly good at it.’

Pennycook has since built on those findings, with one study receiving particularly widespread attention, including an Ig Nobel Award for research ‘that first makes you laugh, then makes you think’. The study in question examined the faux inspirational, ‘pseudo-profound bullshit’ that people often post on social media. To measure people’s credulity, Pennycook asked participants to rate the profundity of various nonsense statements. These included random, made-up combinations of words with vaguely spiritual connotations, such as ‘Hidden meaning transforms unparalleled abstract beauty’. The participants also saw real tweets by Deepak Chopra – a New Age guru and champion of so-called ‘quantum healing’ with more than twenty New York Times bestsellers to his name. Chopra’s thoughts include: ‘Attention and intention are the mechanics of manifestation’ and ‘Nature is a self-regulating ecosystem of awareness.’

A little like the Moses question, those statements might sound as though they make sense; their buzzwords seem to suggest a kind of warm, inspirational message – until you actually think about their content. Sure enough, the participants with lower CRT scores reported seeing greater meaning in these pseudo-profound statements, compared to people with a more analytical mindset.26

Pennycook has since explored whether this ‘bullshit receptivity’ also leaves us vulnerable to fake news – unfounded claims, often disguised as real news stories, that percolate through social media. Following the discussions of fake news during the 2016 presidential election, he exposed hundreds of participants to a range of headlines – some of which had been independently verified and fact-checked as being true, others as false. The stories were balanced equally between those that were favourable for Democrats and those that were favourable to Republicans.

For example, a headline from the New York Times proclaiming that ‘Donald Trump says he “absolutely” requires Muslims to register’ was supported by a real, substantiated news story. The headline ‘Mike Pence: Gay conversion therapy saved my marriage’ failed fact-checking, and came from the site NCSCOOPER.com.

Crunching the data, Pennycook found that people with greater cognitive reflection were better able to discern the two, regardless of whether they were told the name of the news source, and whether it supported their own political convictions: they were actually engaging with the words themselves and testing whether they were credible rather than simply using them to reinforce their previous prejudices.27

Pennycook’s research would seem to imply that we could protect ourselves from misinformation by trying to think more reflectively – and a few recent studies demonstrate that even subtle suggestions can have an effect. In 2014, Viren Swami (then at the University of Westminster) asked participants to complete simple word games, some of which happened to revolve around words to do with cognition like ‘reason’, ‘ponder’ and ‘rational’, while others evoked physical concepts like ‘hammer’ or ‘jump’.

After playing the games with the ‘thinking’ words, participants were better at detecting the error in the Moses question, suggesting that they were processing the information more carefully. Intriguingly, they also scored lower on measures of conspiracy theories, suggesting that they were now reflecting more carefully on their existing beliefs, too.28

The problems come when we consider how to apply these results to our daily lives. Some of the mindfulness techniques should train you to have a more analytic point of view, and to avoid jumping to quick conclusions about the information you receive.29 One tantalising experiment has even revealed that a single meditation can improve scores on the Cognitive Reflection Test, which would seem promising if it can be borne out through future research that specifically examines the effect on the way we process misinformation.30

Schwarz is sceptical about whether we can protect ourselves from all misinformation through mere intention and goodwill, though: the sheer deluge means that it could be very difficult to apply our scepticism even-handedly. ‘You couldn’t spend all day checking every damn thing you encounter or that is said to you,’ he told me.*

* Pennycook has, incidentally, shown that reflective thinking is negatively correlated with smartphone use – the more you check Facebook, Twitter and Google, the less well you score on the CRT. He emphasises that we don’t know if there is a causal link – or which direction that link would go – but it’s possible that technology has made us lazy thinkers. ‘It might make you more intuitive because you are less used to reflecting – compared to if you are not looking things up, and thinking about things more.’

When it comes to current affairs and politics, for instance, we already have so many assumptions about which news sources are trustworthy – whether it’s the New York Times, Fox News, Breitbart, or your uncle – and these prejudices can be hard to overcome. In the worst scenario, you may forget to challenge much of the information that agrees with your existing point of view, and only analyse material you already dislike. As a consequence, your well-meaning attempts to protect yourself from bad thinking may fall into the trap of motivated reasoning. ‘It could just add to the polarisation of your views,’ Schwarz said.

This caution is necessary: we may never be able to build a robust psychological shield against all the misinformation in our environment. Even so, there is now some good evidence that we can bolster our defences against the most egregious errors while perhaps also cultivating a more reflective, wiser mindset overall. We just need to do it more smartly.

Like Patrick Croskerry’s attempts to de-bias his medical students, these strategies often come in the form of an ‘inoculation’ – exposing us to one type of bullshit, so that we will be better equipped to spot other forms in the future. The aim is to teach us to identify some of the warning signs, planting little red flags in our thinking, so that we automatically engage our analytical, reflective reasoning when we need it.

John Cook and Stephan Lewandowsky’s work suggests the approach can be very powerful. In 2017, Lewandowsky and Cook (who also wrote The Debunking Handbook) were investigating ways to combat some of the misinformation around human-made climate change – particularly the attempts to spread doubt about the scientific consensus.

Rather than tackling climate myths directly, however, they first presented some of their participants with a fact sheet about the way the tobacco industry had used ‘fake experts’ to cast doubts on scientific research linking smoking to lung cancer.

They then showed them a specific piece of misinformation about climate change: the so-called Oregon Petition, organised by the biochemist Arthur B. Robinson, which claimed to offer 31,000 signatures of people with science degrees, who all doubted that human release of greenhouse gases is causing disruption of the Earth’s climate. In reality, the names were unverified – the list even included the signature of Spice Girl ‘Dr’ Geri Halliwell31 – and fewer than 1 per cent of those questioned had formally studied climate science.

Previous research had shown that many people reading about the petition fail to question the credentials of the experts, and are convinced of its findings. In line with theories of motivated reasoning, this was particularly true for people who held more right-wing views.

After learning about the tobacco industry’s tactics, however, most of Cook’s participants were more sceptical of the misinformation, and it failed to sway their overall opinions. Even more importantly, the inoculation had neutralised the effect of the misinformation across the political spectrum; the motivated reasoning that so often causes us to accept a lie, and reject the truth, was no longer playing a role.32 ‘For me that’s the most interesting result – inoculation works despite your political background,’ Cook told me. ‘Regardless of ideology, no one wants to be misled by logical fallacies – and that is an encouraging and exciting thought.’

Equally exciting is the fact that the inoculation concerning misinformation in one area (the link between cigarettes and smoking) provided protection in another (climate change). It was as if participants had planted little alarm bells in their thinking, helping them to recognise when to wake up and apply their analytic minds more effectively, rather than simply accepting any information that felt ‘truthy’. ‘It creates an umbrella of protection.’

![]()

The power of these inoculations is leading some schools and universities to explore the benefits of explicitly educating students about misinformation.33

Many institutions already offer critical thinking classes, of course, but these are often dry examinations of philosophical and logical principles, whereas inoculation theory shows that we need to be taught about it explicitly, using real-life examples that demonstrate the kinds of arguments that normally fool us.34 It does not seem to be enough to assume that we will readily apply those critical thinking skills in our everyday lives without first being shown the sheer prevalence of misinformation and the ways it could be swaying our judgements.

The results so far have been encouraging, showing that a semester’s course in inoculation significantly reduced the students’ beliefs in pseudoscience, conspiracy theories and fake news. Even more importantly, these courses also seem to improve measures of critical thinking more generally – such as the ability to interpret statistics, identify logical fallacies, consider alternative explanations and recognise when additional information will be necessary to come to a conclusion.35

Although these measures of critical thinking are not identical to the wise reasoning tests we explored in Chapter 5, they do bear some similarities – including the ability to question your own assumptions and to explore alternative explanations for events. Importantly, like Igor Grossmann’s work on evidence-based wisdom, and the scores of emotion differentiation and regulation that we explored in the last chapter, these measures of critical thinking don’t correlate very strongly with general intelligence, and they predict real-life outcomes better than standard intelligence tests.36 People with higher scores are less likely to try an unproven fad diet, for instance; they are also less likely to share personal information with a stranger online or to have unprotected sex. If we are smart but want to avoid making stupid mistakes, it is therefore essential that we learn to think more critically.

These results should be good news for readers of this book: by studying the psychology of these various myths and misconceptions, you may have already begun to protect yourself from lies – and the existing cognitive inoculation programmes already offer some further tips to get you started.

The first step is to learn to ask the right questions:

Given the research on truthiness, you should also look at the presentation of the claims. Do they actually add any further proof to the claim – or do they just give the illusion of evidence? Is the same person simply repeating the same point – or are you really hearing different voices who have converged on the same view? Are the anecdotes offering useful information and are they backed up with hard data? Or do they just increase the fluency of the story? And do you trust someone simply because their accent feels familiar and is easy to understand?

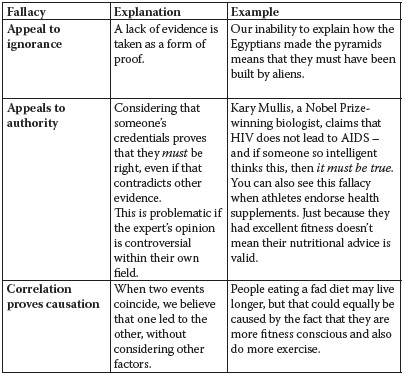

Finally, you should consider reading about a few of the more common logical fallacies, since this can plant those ‘red flags’ that will alert you when you are being duped by ‘truthy’ but deceptive information. To get you started, I’ve compiled a list of the most common ones in the table below.

These simple steps may appear to be stating the obvious, but overwhelming evidence shows that many people pass through university without learning to apply them to their daily life.37 And the over-confidence bias shows that it’s the people who think they are already immune who are probably most at risk.

If you really want to protect yourself from bullshit, I can’t over-emphasise the importance of internalising these rules and applying them whenever you can, to your own beloved theories as well as those that already arouse your suspicion. If you find the process rewarding, there are plenty of online courses that will help you to develop those skills further.

According to the principles of inoculation, you should start out by looking at relatively uncontroversial issues (like the flesh-eating bananas) to learn the basics of sceptical thought, before moving on to more deeply embedded beliefs (like climate change) that may be harder for you to question. In these cases, it is always worth asking why you feel strongly about a particular viewpoint, and whether it is really central to your identity, or whether you might be able to reframe it in a way that is less threatening.

Simply spending a few minutes to write positive, self-affirming things about yourself and the things that you most value can make you more open to new ideas. Studies have shown that this practice really does reduce motivated reasoning by helping you to realise that your whole being does not depend on being right about a particular issue, and that you can disentangle certain opinions from your identity.39 (Belief in climate change does not have to tear down your conservative politics, for instance: you could even see it as an opportunity to further business and innovation.) You can then begin to examine why you might have come to those conclusions, and to look at the information in front of you and test whether you might be swayed by its fluency and familiarity.

You may be surprised by what you find. Applying these strategies, I’ve already changed my mind on certain scientific issues, such as genetic modification. Like many liberal people, I had once opposed GM crops on environmental grounds – yet the more I became aware of my news sources, the more I noticed that I was hearing opposition from the same small number of campaign groups like Greenpeace – creating the impression that these fears were more widespread than they actually were. Moreover, their warnings about toxic side effects and runaway plagues of Frankenstein plants were cognitively fluent and chimed with my intuitive environmental views – but a closer look at the evidence showed that the risks are tiny (and mostly based on anecdotal data), while the potential benefits of building insect-resistant crops and reducing the use of pesticides are incalculable.

Even the former leader of Greenpeace has recently attacked the scaremongering of his ex-colleagues, describing it as ‘morally unacceptable . . . putting ideology before humanitarian action’.40 I had always felt scornful of climate change deniers and anti-vaccination campaigners, yet I had been just as blinkered concerning another cause.

![]()

For one final lesson in the art of bullshit detection, I met the writer Michael Shermer in his home town of Santa Barbara, California. For the past three decades, Shermer has been one of the leading voices of the sceptical movement, which aims to encourage the use of rational reasoning and critical thinking to public life. ‘We initially went for the low-hanging fruit – television psychics, astrology, tarot card reading,’ Shermer told me. ‘But over the decades we’ve migrated to more “mainstream” claims about things like global warming, creationism, anti-vaccination – and now fake news.’

Shermer has not always been this way. A competitive cyclist, he once turned to unproven (though legal) treatments to boost his performance, including colonic irrigation to ease his digestion, and ‘rolfing’ – a kind of intense (and painful) physiotherapy which involves manipulating the body’s connective tissue to reinforce its ‘energy field’. At night, he had even donned an ‘Electro-Acuscope’ – a device, worn over the skull, that was designed to enhance the brain’s healing ‘alpha waves’.

Shermer’s ‘road-to-Damascus moment’ came during the 1983 Race Across America, from Santa Monica, California, to Atlantic City, New Jersey. For this race, Shermer hired a nutritionist, who advised him to try a new ‘multivitamin therapy’ – which involved ingesting a mouthful of foul-smelling tablets. The end result was the ‘most expensive and colourful urine in America’. By the third day, he decided that enough was enough – and on the steep climb to Loveland Pass, Colorado, he spat out the mouthful of acrid tablets and vowed never to be duped again. ‘Being sceptical seemed a lot safer than being credulous’, he later wrote.41

A stark test of his newfound scepticism came a few days later, near Haigler, Nebraska. It was nearly halfway through the race and he was already suffering from severe exhaustion. After waking from a forty-five-minute nap, he was convinced that he was surrounded by aliens, posing as his crew members, trying to take him to the mothership. He fell back asleep, and awoke clear-headed and realised that he had experienced a hallucination arising from physical and mental exhaustion. The memory remains vivid, however, as if it were a real event. Shermer thinks that if he had not been more self-aware, he could have genuinely confused the event for a real abduction, as many others before him have done.

As a historian of science, writer and public speaker, Shermer has since tackled psychics, quack doctors, 9/11 conspiracy theorists and holocaust deniers. He has seen how your intelligence can be applied powerfully to either discover or obfuscate the truth.

You might imagine that he would be world-weary and cynical after so many years of debunking bullshit, yet he was remarkably affable on our meeting. A genial attitude is, I later found out, crucial for putting many of his opponents off their guard, so that he can begin to understand what motivates them. ‘I might socialise with someone like [Holocaust denier] David Irving, because after a couple of drinks, they open up and go deeper, and tell you what they are really thinking.’42

Shermer may not use the term, but he now offers one of the most comprehensive ‘inoculations’ available in his ‘Skepticism 101’ course at Chapman University.43 The first steps, he says, are like ‘kicking the tyres and checking under the hood’ of a car. ‘Who’s making the claim? What’s the source? Has someone else verified the claim? What’s the evidence? How good is the evidence? Has someone tried to debunk the evidence?’ he told me. ‘It’s basic baloney detection.’

Like the other psychologists I have spoken to, he is certain that the vivid, real-life examples of misinformation are crucial to teach these principles; it’s not enough to assume that a typical academic education equips us with the necessary protection. ‘Most education is involved in just teaching students facts and theories about a particular field – not necessarily the methodologies of thinking sceptically or scientifically in general.’

To give me a flavour of the course, Shermer describes how many conspiracy theories use the ‘anomalies-as-proof’ strategy to build a superficially convincing case that something is amiss. Holocaust deniers, for instance, argue that the structure of the (badly damaged) Krema II gas chamber at Auschwitz-Birkenau doesn’t match eye-witness accounts of SS guards dropping gas pellets through the holes in the roof. From this, they claim that no one could have been gassed at Krema II, therefore no one would have been gassed at Auschwitz-Birkenau, meaning that no Jews were systematically killed by the Nazis – and the Holocaust didn’t happen.

If that kind of argument is presented fluently, it may bypass our analytical thinking; never mind the vast body of evidence that does not hinge on the existence of holes in Krema II, including aerial photographs showing mass exterminations, the millions of skeletons in mass graves, and the confessions of many Nazis themselves. Attempts to reconstruct the Krema gas chamber have, in fact, found the presence of these holes, meaning the argument is built on a false premise – but the point is that even if the anomaly had been true, it wouldn’t have been enough to rewrite the whole of Holocaust history.

The same strategy is often used by people who believe that the 9/11 attacks were ‘an inside job’. One of their central claims is that jet fuel from the aeroplanes could not have burned hot enough to melt the steel girders in the Twin Towers, meaning the buildings should not have collapsed. (Steel melts at around 1510° C, whereas the fuel from the aeroplanes burns at around 825° C.) In fact, although steel does not turn into a liquid at that temperature, engineers have shown that it nevertheless loses much of its strength, meaning the girders would have nevertheless buckled under the weight of the building. The lesson, then, is to beware of the use of anomalies to cast doubt on vast sets of data, and to consider the alternative explanations before you allow one puzzling detail to rewrite history.44

Shermer emphasises the importance of keeping an open mind. With the Holocaust, for instance, it’s important to accept that there will be some revising of the original accounts as more evidence comes to light, without discounting the vast substance of the accepted events.

He also advises us all to step outside of our echo chamber and to use the opportunity to probe someone’s broader worldviews; when talking to a climate change denier, for instance, he thinks it can be useful to explore their economic concerns about regulating fossil fuel consumption – teasing out the assumptions that are shaping their interpretation of the science. ‘Because the facts about global warming are not political – they are what they are.’ These are the same principles we are hearing again and again: to explore, listen and learn, to look for alternative explanations and viewpoints rather than the one that comes most easily to mind, and to accept you do not have all the answers.

By teaching his students this kind of approach, Shermer hopes that they will be able to maintain an open-minded outlook, while being more analytical about any source of new information. ‘It’s equipping them for the future, when they encounter some claim twenty years from now that I can’t even imagine, so they can think, well this is kind of like that thing we learned in Shermer’s class,’ he told me. ‘It’s just a toolkit for anyone to use, at any time . . . This is what all schools should be doing.’

![]()

Having first explored the foundations of the intelligence trap in Part 1, we’ve now seen how the new field of evidence-based wisdom outlines additional thinking skills and dispositions – such as intellectual humility, actively open-minded thinking, emotion differentiation and regulation, and cognitive reflection – and helps us to take control of the mind’s powerful thinking engine, circumventing the pitfalls that typically afflict intelligent and educated people.

We’ve also explored some practical strategies that allow you to improve your decision making. These include Benjamin Franklin’s moral algebra, self-distancing, mindfulness and reflective reasoning, as well as various techniques to increase your emotional self-awareness and fine-tune your intuition. And in this chapter, we have seen how these methods, combined with advanced critical thinking skills, can protect us from misinformation: they show us to beware of the trap of cognitive fluency, and they should help us to build wiser opinions on politics, health, the environment and business.

One common theme is the idea that the intelligence trap arises because we find it hard to pause and think beyond the ideas and feelings that are most readily accessible, and to take a step into a different vision of the world around us; it is often a failure of the imagination at a very basic level. These techniques teach us how to avoid that path, and as Silvia Mamede has shown, even a simple pause in our thinking can have a powerful effect.

Even more important than the particular strategies, however, these results are an invaluable proof of concept. They show that there are indeed many vital thinking skills, besides those that are measured in standard academic tests, that can guide your intelligence to ensure that you use it with greater precision and accuracy. And although these skills are not currently cultivated within a standard education, they can be taught. We can all train ourselves to think more wisely.

In Part 3, we will expand on this idea to explore the ways that evidence-based wisdom can also boost the ways we learn and remember – firmly putting to rest the idea that the cultivation of these qualities will come at the cost of more traditional measures of intelligence. And for that, we first need to meet one of the world’s most curious men.