The German philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer believed in reincarnation. He clearly saw that the existence of a newborn has its origin in the worn-out and perished existence of another being in another time. But he also saw this as a riddle. Said he, “To show a bridge between the two (existences) would certainly be the solution of a great riddle.” In this chapter, we will construct this bridge based on the concept of a new kind of memory.

I have spoken of macrobodies of our physical world having grossness because their possibility waves are sluggish. The macrobodies have a property that adds to their grossness. Because of their complexity, once they are “excited” by some interaction, they take a long time to return to their normal “ground” state; in other words, they have a long regeneration time. This allows macrobodies to make memories or records that are practically permanent, that seem irreversible; a tape, audio or video, are examples. I call this classical memory since all you need to understand it is classical physics. An important difference between physical and subtle substances is that the subtle substances do not form classical memory, which requires the grossness of the macrobody.

Do any of our bodies other than the physical form memory of any kind? This is a most important question, because this is the quintessential test of whether they can carry some kind of an identity of lived experience from one incarnation to another. Brahman, the bliss body, comprises all creatures, great and small; manifestations happen within it but do not affect it. But how about the intellect, mental, and vital components of the subtle body?

To their credit, both the Buddhists and the Hindus have always postulated that reincarnation carries learned habits and tendencies from one life to another. Buddhists call these sanskaras and Hindus call them karma. But even these ancient traditions fall short of suggesting a mechanism for transferring the tendencies. This is where our science within consciousness is elucidating.

In the event of every quantum measurement involving us as observer, consciousness not only collapses the possibility wave of the external object of our observation, but also the quantum possibility wave in the brain that gives us self-reference. The collapse in the brain also involves classical memory making. This is clearly content memory, much like an audio or video tape, even though it could be holographic as suggested by the neurophysiologist Karl Pribram,21 and contributes to the personal history with which we identify. For example, I am Amit Goswami, born in Faridpur, India, raised in Calcutta; I moved to United States in my youth, etc.

But another kind of memory associated with quantum measurements in the brain is more subtle. The classical memory made of each measured event is played back whenever a similar stimulus is presented. Because of such repeated measurements of a confined quantum system (that is, not only the stimulus but also the memory playback is measured), the mathematical equation of the system acquires a so-called nonlinearity. This other kind of memory has to do with this nonlinearity due to memory feedback.

Don't get bogged down by mathematical terms such as nonlinearity and what that means; leave it to the mathematician. I am just preparing the context so that you may appreciate the discovery story below. Ordinary quantum mathematics, unencumbered by nonlinearity, gives us waves of possibility and freedom to choose from possibilities. In 1992, a sudden flash of insight convinced me that the nonlinearity of the quantum mathematics for the brain with memory feedback is responsible for a loss of freedom of choice, in other words, what psychologists call conditioning. But how to prove it? The solution of nonlinear equations is notoriously difficult even for mathematicians.

One afternoon I was pondering the problem while devouring a large glass of diet Pepsi at the “fish bowl” (so named because it is surrounded by glass walls) in the University of Oregon student union building when a physics graduate student, Mark Mitchell, joined me, saying, “Why do you look so distraught?” To this I said, “How can one be happy when one has a nonlinear equation to solve?” We got to talking and I continued complaining to Mark about the difficulty of solving nonlinear equations. Mark took one look at my equation and said, “I know how to find a solution. I will bring it to you tomorrow.”

When Mark did not show up the next day, I was not surprised. One learns to accept the limitations of youthful enthusiasm in my profession. So I was doubly surprised when Mark did bring a solution the following day. There were still some glitches, but nothing that could not be worked out (here my greater experience paid off), and the solution was genuine. What we found is this. The more our burden of memory and its playback is, the more compromised our freedom to choose becomes. For any previously encountered stimulus, the probability increases that we will respond to it the same way that we responded to it previously (Mitchell and Goswami 1992). This, of course, is a well-known property of memory; recall enhances the probability of further recall. But the tendency for conditioned behavior lies not in the memory itself, which is physical. The tendency comes from the biasing of the probabilities of those quantum possibilities that we have actualized and lived in the past. The conditioning is contained in the modified quantum mathematics; this I call quantum memory.22

Reader, behold! Objects obey quantum laws—they spread in possibility following the equation discovered by Erwin Schrödinger—but the equation is not codified in the objects. Likewise, appropriate nonlinear equations govern the dynamical response of bodies that have gone through the conditioning of quantum memory, although this memory is not recorded in them. Whereas classical memory is recorded in objects like a tape, quantum memory is truly the analog of what the ancients called akashic memory, memory written in akasha, emptiness—nowhere.

Let's now remember that our experiences of the world as observers not only involves the brain but also the supramental, the mental, and the vital body. In the beginning of the chapter, I noted that subtle bodies cannot make classical memory like a tape recording. This is one of the reasons these bodies are called subtle. The important question now is, Can they make quantum memory?

We have already noted that the physical is needed for the mapping and manifestation of the vital and mental functions that involve movement in space and time. This mapping includes classical memory. Subsequently, if the physical body is excited in this memory state due to some stimulus, consciousness recognizes and chooses to collapse and experience the corresponding correlated states of the vital and the mental body. This repetition is how the mental and vital bodies acquire quantum memory.

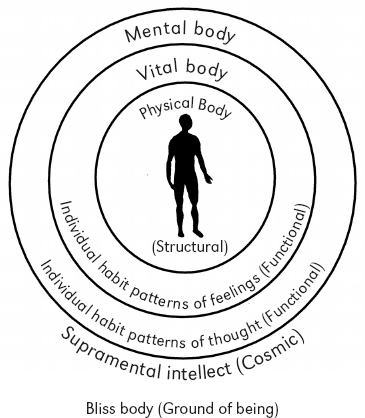

Thus, the memory of the vital and mental bodies is entirely quantum memory that occurs through conditioning of the possibility structure due to repeated experiences, and it results from the same basic dynamics as the quantum memory of the physical body. With many repeated experiences, the quantum memory tends to prevail for any response to any stimulus; this is when our vital and mental bodies can be said to have acquired individual character (fig. 7.1).

Fig. 7.1 The individualization of the vital and the mental bodies.

The identification with this mental and vital character and the classical memory (history) recorded in the brain gives us the ego. Note that since the supramental cannot be mapped in the physical, it cannot be conditioned either. In other words, there is no supramental component to the ego. Interestingly, the Theosophists intuited this distinction between the supramental (which they call “higher mental”) and mental-vital parts (which they call “lower mental”) of the subtle body.

Let's study the message of figure 7.1 carefully. The core of our individual fixity is the physical body; it has a concrete structure. Next comes the vital and the mental bodies: here there is no individual structure, but their fixity comes from our identification with conditioned pattern of habits that we acquire for vital and mental responses. We habitually invoke certain vital energies (feelings) more than others when we respond to emotional situations. We think in character (as a mathematician, as an artist, as a businessman, etc.) when we solve a problem. Thus, our vital and mental bodies are entirely functional. Finally, our supramental intellect and bliss bodies remain unconditioned and universally shared.

Neurophysiologists tell us that there is a full half a second time lag between the time a stimulus arrives and the time of our verbal response (Libet et al. 1979). What happens during this half a second? When a stimulus first arrives, we have many possible quantum responses to it, and we are free to choose among them. The corresponding event of collapse (let's call this the primary collapse event) gives rise to our subject-object split awareness: subject looking at an object. But this subject has freedom of choice, it is not compromised by memory replay, it has no individual habit pattern to respond from. I call the experience of this subject a quantum self experience. It is characterized by creative spontaneity. Now begins memory playback and the conditioning that brings.

The figure 7.2 shows this by the compromise of choice between past (physical, mental, and vital) images and new modes of perception, meaning and feeling included: the probability of choice is greater (indicated by the longer arrow) for the past image than for a new mode. In the secondary collapse event that follows, it is more likely that the past image will collapse than a new perception. As the stimulus percolates down through repeated reflection in the mirror of past memory, the secondary collapse events display more and more tendencies for collapsing a past image rather than a new mode of perception.

Fig. 7.2 The domains of the ego, the preconscious, and the quantum self experiences.

However, in these preconscious stages, there is still some freedom of response. If we exercise this freedom, we experience our quantum self. But by the time the half a second is over and we make our usual verbal response, it is almost a hundred percent conditioned response. If I am looking at a fish (the stimulus), my conditioned mind says “food” if I am a fish eater. I am responding from my ego, strictly according to conditioned patterns of thinking and feeling.

Of course, this is familiar territory for you. You get a new hairdo and dress up nicely in preparation for dinner with your significant other. Your loved one comes home, looks at you but doesn't “see,” and says, “What's for dinner?” You also must have noticed the difference when the response is from the preconscious quantum self: it is spontaneous and joyful, worth dressing up for.

With the ego-response firmly established, there is also a continuity in response. Virtually gone is the discontinuity of the creative response available only in the quantum self.

Let me emphasize once again that it is through this quantum memory processing that we acquire an individual mind and vital body (what we call individual intellect is really part of the individual mind, because the real intellect is supramental and cannot be mapped directly in the brain). Potentially, we all have access to the same mental and vital worlds that are structurally indivisible, but we acquire different propensities and habit patterns that manifest the mental and vital functions in individual ways. Thus, our individual mental (which includes the intellect as intuited and elaborated in the mental) and vital bodies are functional bodies, not structural ones as with the physical body.

Now you can see what happens when we die. The physical body dies with all its classical memories. But the subtle body, the monad, has no structure; there is nothing there to die. The monad with its quantum memory, with its conditioned vital and mental components, remains available as a conglomerate of conditioned vital and mental possibilities. This monad with quantum memory, let's call it a quantum monad, is a viable model of what the Tibetan Book of the Dead and other spiritual traditions identify as the surviving soul.

If somebody else in some future time and place uses a conditioned quantum monad from the past, then, even without the classical memory or prior conditioning in the current life, the vital and mental patterns with which he or she will respond will be a learned pattern, the learned pattern of the quantum monad. In principle, the use of such quantum monads is available to all of us. It seems, however, that certain incarnate individuals are correlated via quantum nonlocality; they have privileged access to the events of each others' lives via nonlocal information transfer (see chapters 4 and 5). It seems that it is these individuals who share the same quantum monad in an ongoing fashion; it is they who can be called the reincarnations of one another. The past life mental and vital propensities that one inherits in this way is called karma in the Hindu tradition.

Thus, the monad, the survivor of the death of the material body, forms a continuum with the physical incarnations because it carries, via its subtle vital and mental bodies, part of the individual identity (fig. 7.3); not the melodrama, not the ego-content, but the character, the tendencies of mental thinking and vital feeling, the (mentally) learned repertoire of contexts, also phobias, avoidances of certain contexts—in other words, both good and bad habit patterns that we call karma. It should now be clear that the propounders of life and death as a continuum are right, and therefore, the Tibetan Book of the Dead is correct—we have proven the validity of its essential point!

Fig. 7.3 The quantum monad and the wheel of karma.

The monad is not only a theme collective that is common to all humanity, as I suggested in chapter 4. It is individualized, possessing vital and mental memory of which contexts have been learned in a particular reincarnational history, a learning that takes place through the modification of the vital body's and the mind's quantum dynamics. At birth, the monad brings karma to the present incarnation. At death, the monad continues, with additional karma accumulated in this life.

Renee falls in love with Sam and learns about romantic love—love expressed as romance. The content—the particular story with Sam—is stored in her brain and is not a part of the quantum monad. But the learning about romantic love is, and it is this mental learning that goes forth from one incarnation to another. The totality of all such learnings forms the quantum memory of the quantum monad.

What entails learning of a context? Quantum leaping to the supramental intellect in a creative insight, we have a momentary mental map of the new context discovered in the insight for which the brain makes a memory. But this does not alter the existing propensities of the mind substantially. That happens when we repeatedly live the insight. The repeated feedback of the brain content memory into the dynamics of experience produces quantum memory in the brain as well as in the mind. Then only can we say that the context has become a learned context of the quantum monad. The same can be said of the vital component of the quantum monad.

For the after-death journey, the idea of the surviving quantum monad complements the nonlocal consciousness of the at-death experience elucidated previously (see chapter 4). Lived content is transferred between incarnations via the nonlocal window; learned contexts and habit patterns are transferred via the vital and mental components of the quantum monad. As discussed in chapter 5, currently there are plenty of objective data that stand witness to the validity of these ideas (also, see below).

When we are alive, we have a public domain of experience—the physical body; but we also have a private domain—the subtle body of the quantum monad. When we die, the public domain disappears, but why should the private disappear since the quantum monad survives?

Many people imagine, in fact, that conscious awareness in the subtle body is lighter, livelier, and presents far greater opportunity for being creative than while living in conjunction with a gross body. Some Hindus think that it is possible to work off karma, even strive toward liberation, while in the subtle body, even without a physical body. And it's not only the Hindus. In a Gallup survey, it was found that fully one third of all adult Americans believe that they will grow spiritually in Heaven (Gallup 1982).

Souls, looked upon in the way developed here as discarnate quantum monads, cannot have subject-object awareness, cannot grow spiritually in any tangible sense, and cannot be liberated by doing spiritual work in the heavens. They carry the conditioning and the learning of previous incarnations, but they cannot add to or subtract from the conditioning by further creative endeavors, which can be done only in conjunction with earthly form. The reason is subtle.

The truth is, collapse of the possibility wave requires a particular self-referential dynamics called tangled hierarchy (a circularity of hierarchies as explained below) which only a material brain (or a living cell and its conglomerates) provides.

I have already mentioned that there is a circularity, a breakdown of logic, when we consider the role of the brain in relation to quantum measurement and the collapse of the quantum possibility. Undeniably, collapse creates the brain in the sense that it is our observation that collapses quantum possibilities of the brain to actuality. On the other hand, how can we deny that there is no collapse without the presence of a sentient observer's brain? This tangled hierarchy characterizes the quantum measurement in the brain.

It will help to understand the difference between a simple and a tangled hierarchy. Consider the reductionist picture of the material world. Elementary particles make atoms, atoms make molecules, molecules make living cells, cells make brains, brains make observer/subjects, us. At each stage, cause flows from the lower level of the hierarchy to the higher level. That is, the interaction of atoms is believed to be the cause of the behavior of molecules, interaction between cells (neurons) causes the behavior of the brain, and so forth. Ultimately, the interactions of the lowest level, the elementary particles, are believed to cause everything else. This is a simple hierarchy of upward causation.

But when we say that quantum measurements take place as a result of our observations, we are violating the rules of a simple hierarchy. We are acknowledging that the elementary particles, the atoms, all the way up to the brain, are waves of possibility, not actuality. And we, the observers, are required to choose (collapse) actuality from possibility. We are here because of the brain, no doubt, but without us the state of the brain would remain in possibility. This is suggestive of a fundamental tangled hierarchy involved in the quantum measurement in the brain.

To see this, consider the liar's paradox, the sentence, “I am a liar.” Notice that as the predicate of the sentence defines the subject, the subject of the sentence redefines the predicate; if I am a liar, then I am telling the truth, but then I am lying, and so on ad infinitum. This is a tangled hierarchy because the causal efficacy does not lie entirely with either the subject or the predicate but instead fluctuates unendingly between them. But the real tangle of causal efficacy in the liar's paradox is not in the sentence “I am a liar”; it is in our consciousness, in our knowledge of the metalanguage rules of English (Hofstadter 1979).

Try the paradox with a foreigner; he will ask, “Why are you a liar?” failing to appreciate the tangle because the rules of metalanguage are obscure to him. But once we know and abide by these metalanguage rules, looking at the sentence from “inside,” we cannot escape the tangle. When we identify with the sentence, we get caught: the sentence is self-referential, talking about itself. It has managed to separate itself from the rest of the world of discourse.

Thus, realizing that the quantum measurement in an observer's brain is a tangled-hierarchical process helps us to understand our self-reference—our capacity to look at the (collapsed) object of our observation separate from us, the subjects. Note also that this subject-object split is only an appearance. After all, the self-referential separation in the liar's paradox of the sentence from the rest of the world of discourse is only an appearance. The same thing happens for the quantum measurement in the brain. The subject—that collapses, that chooses, that observes (or measures), that experiences—dependently co-arises with awareness of the object(s) that are observed and experienced; they dependently co-arise (as appearance) from one undivided, transcendent consciousness and its possibilities.

A tangled hierarchy in the brain's mechanism for quantum measurement is responsible for the self-reference, the appearance of the subject-object split in consciousness. Since we identify with the self (which I call the quantum self) of this self-reference, the appearance takes on the aura of reality. This identification is also the source of the apparent subject-object duality. However, ultimately, we, who are the causal force behind the tangle of the self-referential sentence, transcend the sentence and can jump out of the sentence. Can we similarly jump out of our self-referential separateness from reality? We can. This is what is referred to by such exalted concepts as moksha and nirvana.

Ordinary quantum amplification by a measurement apparatus, such as in our observation of an electron using a Geiger counter, is simple-hierarchical. The micro quantum system that we are measuring (electron) and the macro measurement apparatus (Geiger counter) we are using for amplification to facilitate our seeing is distinct; what is quantum system and what is measurement apparatus is clear. But in a self-referential system, be it a brain or a single living cell, this distinction is blurred since the supposed quantum processor of the stimulus and the supposed amplifying apparatuses are of the same size.23 There is feedback, and in effect, the quantum processor and the amplifying apparatuses “measure” one another, creating an infinite loop because no number of such “measurements” can by themselves ever collapse actuality from possibility, as only consciousness can from a transcendent level. This is a tangled hierarchy.

It's like the Escher picture of drawing hands (fig. 7.4) in which the left hand draws the right and the right hand draws the left. But in truth, neither can ever quite do the drawing; their drawing each other is only appearance. It takes Escher from outside the system to draw them both.

Fig. 7.4. “Drawing Hands” by M. C. Escher. From the “immanent” reality of the paper, the left and the right hands draw each other, but from the transcendent inviolate level, Escher draws them both.

The subtle supramental, mental, and vital bodies do not differentiate between micro and macro; in effect, this makes it impossible to precipitate a tangled-hierarchical quantum measurement of the vital, the mental, or the supramental body by itself. Therefore, no tangled hierarchy, then no collapse of the quantum possibilities.24

Of course, the possibility waves of the vital, mental, and the supramental bodies collapse when they are correlated with the possibility waves of the physical body (even the correlation with a single cell is sufficient for collapse, although the mapping of the mind is only indirect in living organisms until the brain develops, and the direct mapping of the supramental is waiting further evolution) in one fell swoop of self-referential quantum measurement of the latter. But there is no collapse of the quantum possibility waves of a discarnate quantum monad without the aid of a correlated physical body/brain. Consequently, a discarnate quantum monad is devoid of any subject-object experience. We cannot be overoptimistic about the possibility of working off karma while in after-death sojourns. We may have to settle for a less melodramatic existence.

(Are you disappointed that there is no melodrama after death? I sympathize. When I was a teenager, I read a most wonderful novel by a Bengali writer, Bibhuti Banerji, about a spiritual love story in Heaven. I even fantasized translating the book into English, so enamored was I with its message. I guess truth is sometimes more disappointing than fiction!)

If, in the nonlocal consciousness of the state of death, the dying person recognizes the dim light of pure consciousness of the fifth bardo, the person has a choice. He can choose to reincarnate or to assume the Sambhogakaya form of the quantum monad and be free from human reincarnations. For such a person, the only karma left is one of joyful service to all those who need it. (How does such a person render service? See below.)

In the Mahayana Buddhist tradition, it is a high ideal to not take personal salvation but to remain in service, helping all people to arrive in nirvana. In death, this consists of deliberately not seeing the clear light of the fourth bardo and choosing to recognize the dim light of the fifth bardo instead. What is the hurry?

As mentioned in chapter 5, some of the reincarnation data consists of reincarnational-memory recall of content, for which the opening into the nonlocal window of the individual is enough. But there are also data of transmigration of special propensities or phobias that now can find explanation in terms of their actual transmigration via the quantum monad from one incarnation to the next.

What gives rise to the propensities? The quantum memory of the inherited quantum monad makes sure that contexts learned in the previous incarnations are recalled with greater probability. How do phobias arise? They are due to the avoidance of certain responses, the avoidance of collapsing certain quantum possibilities into actuality because of past-life trauma. Why does hypnotic regression therapy work? The recall of a past-life trauma amounts to reenacting the scene, thus giving the subject another opportunity to creatively collapse the suppressed response.

With the quantum memory from a past life helping us, it is now easy to understand the phenomenon of genius. An Einstein is not built via childhood learning in one life; many previous lives contributed to his abilities. The inventor Thomas Edison intuited the situation correctly when he said, “Genius is experience. Some seem to think that it is a gift or talent, but it is the fruit of long experience in many lives. Some are older souls than others, and so they know more.”

Even the conditioning of the vital body can be transmitted. Consider the following case, investigated by Ian Stevenson. The subject, an East Indian man, clearly remembered that in his previous life he was a British officer who had served in World War I and was killed in battle by a bullet hitting his throat. The man was able to give Stevenson many details of the Scottish town of his previous incarnation, details quite inaccessible to him in the present life. These details were later verified by Stevenson.

So far it is all a case of reincarnational-memory recall via the nonlocal window. What is spectacular in this man's case were twin birthmarks on both sides of the throat, which Stevenson thought were consistent with bullet marks. It seems that the past-life trauma, recorded as a propensity of the vital body, had followed this man to this life and given him an unforgettable memory, carried in his body through the scars. Read Stevenson's vast work for this and many other cases of transmigration of the vital body's conditioning (Stevenson 1974, 1977, 1987).

“I find myself thinking increasingly of some intermediate ‘nonphysical body’ which acts as the carrier of these attributes from one life to another,” says Stevenson. I agree: the subtle body of the quantum monad is the carrier of the attributes from one life to another.

By fleshing out the notion of survival and by identifying what survives from one incarnation to another, this extended model enables us to understand aspects of mediumistic communication that go beyond communication through the nonlocal window. How does a medium communicate with a discarnate quantum monad in “Heaven”?

Consciousness cannot collapse possibility waves in a quantum monad in the absence of a physical body, but if the discarnate quantum monad is correlated with a medium, collapse can happen. Clearly, channelers are those people who have a particular talent and the openness to act in that correlated capacity; by the purity of their intention, they can establish nonlocal correlation with a discarnate quantum monad. It is well-known that while a channeler channels, his or her habit patterns—manner of speaking, even thinking—undergo amazing changes. This is because, while the medium is in communication with the discarnate monad, the subtle body of the medium is temporarily replaced by the subtle body of the discarnate quantum monad whose habit patterns the medium displays. Note that historical information—for example, in xenoglossy, speaking an unknown foreign language—still has to come in through quantum nonlocal channels, but the information would be very difficult to process without help from the propensities that the deceased had that remain latent in the discarnate quantum monad.

The philosopher Robert Almeder (1992) has discussed the case of the medium Mrs. Willett, making the same point that I am making. Mrs. Willett displayed philosophical savvy demonstrating that she was in touch with propensities she did not have—the know-how of philosophical argumentation. These propensities could likely have come from discarnate quantum monads that learned and retained the propensities.

In the case of the channeler JZ Knight, whom I have seen in action when she channels the entity called Ramtha, there are records of her channeling extending over two decades. As Ramtha, JZ becomes a spiritual teacher of considerable originality. The records suggest that the content of Ramtha's spiritual teaching has changed over the years following the changes in the models of new-age spirituality. It makes sense to say that JZ supplies the content while Ramtha provides the contextual ability to shape the content.

There are cases of automatic writing that deserve similar explanation. The prophet Muhammad wrote the Koran, but he was practically illiterate. Creative ideas, spiritual truths, are available to everyone, but creativity requires a prepared mind, which Muhammad did not have. The problem is solved for Muhammad because the Archangel Gabriel—a Sambhogakaya quantum monad—lends Muhammad a prepared mind, so to speak. The experience also transformed Muhammad. A spectacular recent case of automatic writing is A Course in Miracles—a book that gives a modern interpretation of many Biblical teachings—which was channeled through the work of a couple of psychologists, one of whom was not particularly sympathetic to what she was channeling.

On the negative side, possession is a similar phenomenon as channeling, except that the discarnate quantum monad that becomes correlated with the possessed is not one of angelic character.

Previously, I introduced the idea that angels belong to the transcendent realm of archetypes. These are the formless angels.

People who take rebirth in Sambhogakaya form, which is another metaphor for saying that these people no longer identify with any incarnate bodies, have no further need for quantum monads to transmigrate propensities and unfinished tasks from one life to another; they have fulfilled their contextual obligations. Thus, their discarnate quantum monads become available to all of us, to lend their mind and vital bodies to us, if we are receptive to their service. They become a different kind of angel, an angel in the form of a fulfilled quantum monad (the Sambhogakaya form). (For recent perspectives on angels, read Parisen 1990.)

In Hinduism, there is the concept of arupadevas and rupadevas. Arupadevas—devas without form—are purely archetypal contexts, part of the theme collective. But rupadevas, I believe, represent different entities; they have individual vital and mental (that includes the mental maps of the intellect) bodies. They are the discarnate quantum monads of liberated people.

Similarly, in Buddhism, there are archetypal, formless bodhisattvas, for example, Avalokitesvara, the archetype of compassion. In contrast, liberated Buddhists, when they die, become bodhisattvas in the discarnate form of the fulfilled quantum monad; they choose to go out of the death-rebirth cycle and be born in the Sambhogakaya realm. This rebirth as the discarnate quantum monad beyond the birth-death cycle is part of what Tibetans call the fifth bardo experience.

Buddhists, in general, are asked to become bodhisattvas—to stay at the doorway of merging into the whole but not to merge until the whole humanity becomes free of samsara. Hence, the famous Quan Yin vow: “Never shall I seek nor receive private individual salvation; never shall I enter the final peace alone; but forever and everywhere, shall I live and strive for the redemption of every creature throughout the world.” A similar prayer is found in the Bhagavata Purana of the Hindus: “I desire not the supreme state . . . nor the release from rebirth; may I assume the sorrow of all creatures who suffer and enter into them so that they may be made free from grief.”

Think of it in another way. Ellen Wheeler Wilcox wrote about the idea of meeting God face to face, or of seeing the clear light in her poem, “Conversation”:

God and I in space alone . . .

and nobody else in view . . .

“And where are all the people,

Oh Lord” I said,

“the earth below

and the sky overhead

and the dead that I once knew?”

“That was a dream,” God smiled

and said: “The dream that seemed to

be true; there were no people

living or dead; there was no earth,

and no sky overhead,

there was only myself in you.”

“Why do I feel no fear?” I asked,

“meeting you here in this way?

For I have sinned, I know full well

and is there heaven and is there hell,

and is this Judgment Day?”

“Nay, those were but dreams”

the Great God said, “dreams that have ceased to be.

There are no such things as fear and sin;

there is no you . . . you never have been.

There is nothing at all but me.”

Yes, that is the reality of the clear light; in the clear light nothing ever happens, and that must include seeing the clear light itself. For the creation to continue, the appearance of separation must continue. And since consciousness continues its illusory play, why not continue to play in it? First play in the physical body, and then without it. But play you do, because play is joy!

So the Vaishnavites in India postulate that the individual monad (called jiva in Sanskrit) always retains its identity. It makes sense. If the play is eternal, so is the (apparent) separation of the jiva from the whole.

The service or joyful play of angels, rupadevas, and bodhisattvas comes not only in spectacular automatic writing that gives us the Koran or A Course in Miracles but also as inspirations and guidance in our most difficult moments. Bodhisattvas and angels are available to all of us. Their intention to serve is omnipresent. When our intention matches theirs, we become correlated; then they act through us and serve through us.

When the East Indian sage Ramana Maharshi was dying, his disciples kept asking him not to go. To this finally Ramana said, “Where would I go?” Indeed, a discarnate quantum monad such as Ramana's would live forever in the Sambhogakaya realm, guiding whoever wanted his guidance.

Is it possible to “be in” the quantum monad while living, while in our incarnate bodies? In out-of-the-body and near-death experiences, people have autoscopic vision (vision of themselves) from a vantage point of hovering over their own body that can be explained as nonlocal seeing (see chapter 5). In these experiences, however, there is more than nonlocal viewing. People who have these experiences report that they were out of the body, that their identity shifted from the usual physical-body centered identity. To what?

I think the identity shifts to one centered in the subtle body conglomerate of the quantum monad. A woman, for example, was out of her body while she was being operated upon. She later reported that in that state she was totally unconcerned about the outcome of the surgery, about her physical well-being, which was “absurd” since she had small children. But the absurdity gives way to making sense when we realize that in these experiences people do not identify with their present situations, their body and brain and the accompanied history; instead, they identify with their quantum monad, which has no history, only character.

There is some controversial data that people and animals (for example, dogs) see something (a “ghost?”) at the very places where subjects later report having been during their OBE (Becker 1993). Do we “see through” a quantum monad while the quantum monad (and its parallel physical body) is nonlocally “seeing through” us? Such a reciprocity between correlated entities would certainly make sense. When we see an apparition, perhaps we project what we see inside to the outside where we perceive the event to be taking place.

I think that spiritual visions also have a similar origin. Many people have experiences of seeing Jesus, the Virgin Mary, or Buddha, or their deceased spiritual guru. At the Hollywood Vedanta Society, where I occasionally give workshops, people sometimes have visions of Swami Vivekananda, the founder of the society. These visions could be the result of inner experiences projected outside.

Let me briefly mention one of the latest, extremely controversial, data regarding communication with discarnate quantum monads. In this data, discarnate quantum monads are supposedly communicating with specific groups of experimenters through machines—tape recorders, radios, TV, even computers (Meek 1987). This is referred to as the electronic voice phenomenon (EVP). If substantiated, this will eliminate the question of fraud in survival data. Of course, then a very difficult question arises: how does the discarnate quantum monad without the help of a physical body and physical interaction (which is forbidden) affect a material machine?

I think the discarnate quantum monad, first of all, becomes correlated with a medium, so that its possibility waves can collapse along with those of the medium. The rest is perhaps psychokinesis with amplification. Similar psychokinetic powers are witnessed in the poltergeist phenomenon. Perhaps discarnate quantum monads add greater psychokinetic power to a medium via some mechanism of amplification that we have yet to understand. Clearly, the idea of the quantum monad gives us a new way to think about a great deal of unexplained data. We will learn more as we continue with the adventure in the new science.

In the Republic, Plato tells a story in which the idea is conveyed that we choose our incarnations, “Your destiny shall not be allotted to you, but you shall choose it for yourselves.” To what extent is this true? Let's find out in the next chapter.

In the preface of the book, I promised that the basic questions of reincarnation will be addressed and answered in this book with the adequate development of a physics of the soul. Let's summarize and see to what extent the promise has been kept.

Recognize once again that if you think of the soul without the backing of the right physics, you fall prey to dualism, and questions like, How does the nonmaterial soul and the material body interact without a mediator? haunt you. The dualism problem is solved in quantum physics by realizing that both the nonmaterial soul and the material body are mere possibilities within consciousness and consciousness mediates their interaction and maintains their parallel functioning.

Classical Newtonian determinism-oriented physicists say things like, The more we study the universe, the more we find it meaningless. Our soul sets the contexts in which meaning enters our lives. This contextualizing aspect of the soul is the supramental intellect or the theme body. Meaning is processed by the mind and expresses itself through a body whose plan is unfolded via the making of the representations of the morphogenetic fields of our vital body. Quantum physics, by making the concept of the nonmaterial soul a viable scientific concept, also revives meaning as a scientific pursuit of our lives.

But I call the soul a quantum monad, an individualized unit. How does the soul become individualized? The answer is: through the individualization of the mind and the vital body. This many-splendored individualization takes place through what I call quantum memory.

What is quantum memory? Memory that you are familiar with takes place because of the modification of the structure of something physical. Large macrobodies take a long time to regenerate from any such modifications of structure; hence, the modifications are retained as memory, and I appropriately call them classical memory. A magnetic tape recording is a good example. In contrast, quantum memory takes place via the modification of probabilities of accessing the various quantum possibilities that we collapse as actualities in our experience.

Every quantum possibility, be it of the brain, the mind, or the vital body, comes with an associated probability determined by quantum dynamics. The first time you actualize a possibility in response to a stimulus, your chance of actualizing it depends on the probability given by the appropriate quantum dynamics. Suppose for a particular possibility, the probability is 25 percent. Your consciousness has the freedom to choose this particular possibility into actuality anytime with the caveat that for a large number of such collapse events the probability constraint must be fulfilled, that is, for a large number of collapse events involving this possibility, this possibility may become actuality only one fourth of the time. But with subsequent experience of the same stimulus, the probabilities are modified; they are biased more toward recapitulating the past responses; this is conditioning. So now with conditioning, the probability of the aforementioned possibility to be actualized may be biased toward near 100 percent, in which case the response is no longer free at all. It is now a habit, a memory—quantum memory.

The complete model of reincarnation, the one that agrees with all the reincarnational data, can now be stated: Our various incarnations in many different places and times are correlated beings, correlated by our intentions; information can transfer between these incarnations by virtue of the quantum nonlocal correlation. Behind the discreteness of the physical body and lived history of these incarnations, there exists a continuum, a continuum of the unfolding of meaning. Formally, the continuum is represented by the quantum monad, a conglomerate of unchanging themes and changeable and evolving vital and mental propensities, or karmas.

21However, the known laws of physics do not allow such memory to be completely irreversible.

22Physicist Howard Carmichael (private communication with author) has shown by statistical “Monte Carlo” calculations that the solution of nonlinear Schrödinger equations for a photon in a resonant cavity also acquires conditioning, thus providing an independent verification of the idea of quantum memory.

23This point is particularly emphasized by Stapp 1993.

24The question can be raised: Can a physical body alone, if it has a tangled-hierarchical dynamics built into it, precipitate self-referential collapse without teaming up with a mental or a vital body? We may have to build a quantum computer to find the answer!