One of the great paradoxes of death is the issue of the fear of death. Generally speaking, people believe that death is a hard thing, a bad thing. They fear death, hence the tendency to deny its inevitability.

It is interesting that primitive people are not particularly afraid of death but are afraid of the dead. They are more sensitive to the dead and seem to be affected by them. And the more they are affected by them, the more they are fearful of them. It took the discovery that the dead can affect us only if the living cooperate (by being afraid, by being sensitive) to change our fear of the dead. Disbelief became the protection against any harm by the dead.

And then a new fear gripped us—the fear of death itself. Or rather, the loss of fear of the dead revealed our fear of death itself. We intuited in the early days of civilization that the after-death state is a journey of the soul into dark Hades, and we became afraid. As a Greek poet wrote, “Death is too terrible. Frightening are the depths of Hades.” This fear continues today. “Now I am about to take my last voyage, a great leap into the dark,” wrote the author Thomas Hobbes, echoing this fear.

The development of materialist science should have eliminated our fear of Hades. If we are simply matter, only atoms (or genes) that do survive death, then why fear Hades? But what science has tried to accomplish philosophically has not changed people's (scientists included) personal fear of death. The point is that the fear of death is irrational in materialist science. The fear of the irrational has become irrational fear.

Why is death feared as a bad thing? How can we consider something bad before we have experienced it? From where does the idea of badness of our personal death arise? Materialist/behaviorist models of ourselves cannot answer such questions very well.

And yet a different perspective of death also exists. The psychologist Carl Jung put it well when he wrote, “Death is the hardest thing from the outside and as long as we are outside of it. But once inside you taste of such completeness and peace and fulfillment that you don't want to return.” Jung's statement was prompted by a near-death experience he had when he suffered a heart attack in 1944.

Many people in our culture have benefited from near-death experiences. Such people often experience being out of the body and often have spiritual experiences. As a result of such experiences, freed from the dominant body identity, they shed their fear of death. This is a good thing to remember: death may be very different from inside than it appears from outside.

Admittedly, and especially when we look at death from a materialist worldview, from the outside, death looks terminal for our life, mind, and consciousness. But from the inside Jung felt (as do subjects of near-death experiences in general) that death is a freeing of consciousness from the shackles of the body. It is impossible to make sense of such a statement in a materialist model of the world.

You may argue, correctly I believe, How can near-deathers be “inside” death when they don't really die? But this raises the still more intriguing question: Is it possible to understand death without dying, without even the near-death experience, in such a way that the fear of death disappears?

Jung's statement implies that consciousness survives death. And it does not necessarily take a near-death experience to reach that conclusion. Many people living normal lives intuit that their consciousness is not limited to their body and that, even when their bodies die, consciousness will survive in some way. It is this kind of direct intuition that rids people of the fear of death.

The point is that only truth can set us free from fear. If materialism were truth, all true believers of materialism, including most scientists, would be free from their fear of death. But they are not. On the other hand, people who deeply realize that consciousness extends beyond the material world, beyond their ego, are more or less free of the fear of death. As Dorothy Parker said, “Death, where is thy sting-a-ling-a-ling?”

It is known that in cultures where reincarnation is accepted the fear of death abates considerably. The person can relax, because in some way or other she will not die but will come back. We are not afraid to lose consciousness in sleep! As you can see, reincarnation is another way of achieving a sort of immortality, not in the same body but through the continuity of some “essence of life.” The poet Walt Whitman, a connoisseur of reincarnation, expressed the same sentiment:

I know I am deathless,

I know this orbit of mine cannot be swept by a

carpenter's compass. . . .

And whether I come to my own today or in ten

thousand or ten million years,

I can cheerfully take it now, or with equal

cheerfulness I can wait . . .

I laugh at what you call dissolution,

And I know the amplitude of time. . . .

To be in any form, what is that?

(Round and round we go, all of us, and ever come

back thither) . . .

Believing I shall come back again upon the earth

after five thousand years. . . .

(Whitman; quoted in Cranston and Williams 1994, 319)

To some of us, “I will come back” is certainly reassuring, but how much more reassuring it would be if we knew how we'd come back. Can we gain some control over what happens at death? This question gives rise to the idea of dying consciously, dying creatively.

When I think of creative dying, I sometimes think of Franklin Merrell-Wolff. I met this wonderful spiritual philosopher and teacher when he was 97 years old. During the next year, his last, I spent about twelve weeks in his presence, including a one-month period which I consider the happiest time of my life. I still refer to it as Shangri-la.

During my time with him, I noticed that one of Dr. Wolff's preoccupations was, not surprisingly, death. He wanted to die consciously, he repeatedly said to me. But most times, we would just sit quietly. I felt, for the first time, being in Dr. Wolff's presence.

I think he wanted to die in this state of pure being. Did he succeed? I was not there when he died; actually, nobody was with him. He died from pneumonia at around midnight after he was left alone, apparently sleeping, for a few moments. When Andrea, his nurse-companion and student, returned, Dr. Wolff was dead. The reports I got from all those who attended Dr. Wolff during his two-week illness was that he maintained his sense of humor, his kindness, and being, if you will, until the very end.

How can one die consciously? Is it important to die consciously? Death is this wonderful opportunity to be liberated or, at least, to communicate via our nonlocal window with our entire string of reincarnations; thus, the importance of conscious dying cannot be overstated. The first question—How can one die consciously?—is the much more difficult one to answer, although there is a whole yoga called death yoga, which can teach us that.

The essence of reality, when you comprehend it with a science within consciousness, is that there is no death, there is only the creative play of consciousness. And ultimately, the play is only appearance. The Hindu philosopher-sage Shankara is emphatic: “There is neither birth nor death, neither bound nor aspiring soul, neither liberated soul, nor seeker after liberation—this is the ultimate and absolute truth.” So creative dying, death yoga, liberation itself, has this one goal: to comprehend this true nature of reality that is consciousness.

We are afraid of death because we don't realize the truth that we are one with the whole, and we suffer as a result. In the last chapter, I spoke of the various stages patients go through when they discover their imminent mortality—denial, anger, bargaining, and all that. You have been there, too, if not in this life (yet), many times in your past incarnations. You have denied that your ego will die, you have been angry about its inevitability, you have tried to bargain with God, thinking that God is separate from you. Where has that got you? As long as you are convinced of the reality of your ego, the suffering recurs.

Sure, when you are young and healthy, you can philosophize. Life and death, joy and suffering, sickness and health—these are the polarities of the human condition. Perhaps the best strategy is to accept these polarities. Meditate “this too shall pass” when suffering hits. When death knocks on your door, you can remind yourself that you will be born again in another life, so there is no big deal about dying in this one. The problem with this kind of thinking is that a true acceptance of this philosophy does not come easy. In fact, it requires liberation or a state of being that is pretty close to it.

Twenty-five hundred years ago, a prince in India who was kept isolated from all suffering for his first twenty-nine years, went on an unsanctioned tour of his city and discovered that there is sickness, that people get old and die. This prince Gautama, who later became Buddha, the enlightened one, realized that life is recurrence of suffering. He discovered the virtue of nonattached living, meditating on “this too shall pass” not only when suffering but also when pleasured in order to move toward nirvana, the extinction of desires—liberation.

A true acceptance of the polarities of our being can lead to desirelessness—a falling away of desires, an abatement of preferences; many sages throughout history have stood witness to that. But look at some people striving for liberation in the spiritual path, embracing pain (if only the pain of boredom), and you wonder, “Aren't these people just trading off?” They may remind you of a story. Two old friends are talking. One of them complains of gout. The other one gloats, “I never suffer from gout. A long time ago, I taught myself to take a cold shower early every day. That's a sure prevention of gout, you know.” The other friend scoffs, “Yes, but you've got cold shower, instead.”

You want to be free (of suffering), but you don't want to take cold showers for it. The good news is that there is an avenue to liberation even for you, a way to escape the birth-death cycle. Welcome to death yoga, learning how to die consciously, with creativity, and so be liberated. Any creative experience is a momentary encounter with the quantum self, but in a creative experience—outer or inner—while you are living fully, you have to return from the encounter back to ordinary reality where your ego-identity usually takes hold once again. But in a creative encounter with God at death, there is no coming back. Such an experience can truly liberate you.

And if, perchance, you are not convinced that this philosophy of liberation is for you because “life is fun in spite of death, pleasure is fun in spite of the pain that follows,” you need to expand your concept of liberation. You have intuited a philosophy deeper even than liberation philosophy. Liberation philosophy is based on “life is suffering,” and it suits some people just fine. After all, all this is maya, an illusory play of consciousness. But wait! The illusory play has a purpose—to comprehend creatively all that is possible, all that is potential in consciousness. And creative comprehension is ananda—spiritual joy. So in this philosophy, the play is the thing, and life is joy. In this philosophy, what is the role of liberation? It is to achieve true freedom of choice and to live creatively all the time.

For “life is suffering” seekers, liberation is freedom from the birth-death cycle, and death leads to a merging into the unity of reality forever. For “life is joy” seekers, liberation is having the choice, to be born or not to be born is a question they would like to keep forever open, forever having the option to partake of all that life offers, including its polarities, but to partake of it creatively.

So you can look at the ultimate aim of death yoga either as a way to opt out of the birth-death cycle or a way to achieve ultimate freedom—freedom to choose if and when to take birth again. At the least, death yoga can enable you to stay conscious in parts of the dying process, crucial in order to have a real choice in your next incarnation.

Try to meditate in the midst of a marketplace. It is quite a challenge to concentrate on your breath or a mantra when there are so many distractions. Sounds and sights, smells and tastes abound. People buying and selling have a frenetic energy; that too sends your efforts awry. Isn't it easier to meditate in a quiet corner without distractions?

Similarly, life is full of distractions. In a sense, it is also a marketplace of buying and selling, exchange of possessions and relationships. Comparatively speaking, death is a quiet corner where things and possessions, people and relationships, leave you alone.

Creativity is an encounter of the ego and the quantum self (May 1975; Goswami 1996). At death, as we have seen, consciousness begins to withdraw from the physical body. While it continues to collapse correlated possibility waves so that experience goes on, the center of identity shifts first to the vital-mental body, then past that to the realm of archetypes (the theme body). When the identity shifts in this way, the ego becomes more fluid, as in a dream; it has a minimum of the fixity that we experience during our ordinary waking hours, a fixity that is the utmost obstruction against the creative encounter.

A good analogy is the flow experience that you have when you forget yourself in the dance of creation with the quantum self. Flow is when the dance dances you, the music plays you, the pen writes on the paper as if it is just happening and you are not doing it. We sometimes naturally fall into this state in our pursuits, but we can also practice to maximize the chance of falling into them. Practicing to be in the creative state of flow as we die is a purpose of death yoga.

In the Upanishads, it is said that people at death go to Chandraloka—the realm of the moon (obviously a station between Heaven, the transcendent, and Earth, the ordinary immanent realm). Here they are asked, “Who are you?” Those who cannot answer are destined for reincarnation as determined by their karmic bondage. But those who answer “I am you” are allowed to proceed on their great journey (Abhedananda 1944). But notice how paradoxical the phrase “I am you” is. I am separate because I can see “I am,” and yet I also see my identity with you. This is the nature of the encounter between the ego and the quantum self.

Creative acts require four stages: preparation, incubation (unconscious processing), encounter and insight, and manifestation. Creativity in death is no exception. In the following pages, let's look into the details of these stages. One good thing about death is that you don't have to go through hoops to achieve it. It costs you nothing and has the potential to give you everything. What a treat!

When should you begin preparing for death? There is really no reason why you should not start right now. Some people regard their whole life as a preparation for death (somewhat like people who eat their whole dinner in preparation for the dessert), and they are not wrong to think and act in this way (death is their “dessert”). But if you have lived “normally,” then when to prepare for death has special significance. It is the beginning of your particular practice of death yoga.

You must begin such preparation when you know you have a terminal disease—that's easy. But when there is no such clear indication, what then?

When you are old, if you watch for them, some preliminary symptoms of the eventual withdrawal of consciousness from life become clear to you. The physical body may get weak. You may experience periods of dry mouth and difficulty in breathing. You may also have difficulty in recognizing people. These withdrawal symptoms may also appear as a general reduction in the need to conceptualize, a tendency toward less aggressiveness in doing or accomplishment, and a lessening of desire for things. These symptoms are further accompanied by a natural tendency to fall into nondoing, a disinterest in the contents of the mind that is close to emptiness. Why these tendencies? There is a gradual decoupling of the correlated actions of the mental and physical, or of the physical, mental, and vital. When this becomes fairly frequent, it is time to prepare in earnest.

Of what does preparation consist? Although documented best with terminally ill patients, the truth is that most of us go through the stages of denial, anger, bargaining, and depression when we are confronted with death, even vaguely (as and when we are old and not so healthy and begin to notice the preliminary withdrawal symptoms above). The first essential step of preparation is to go through these stages, ending in acceptance. Acceptance is the opening of the mind toward the creative possibilities of death. The psychologist Carl Rogers gave high value to an open mind for creativity.

In a Zen story, a professor goes to see a Zen master to learn about Zen. While the Zen master prepares tea, the professor begins to give the Zen master an earful of what he knows about Zen. When the tea is ready, the Zen master starts pouring the tea into the professor's cup. But he goes on pouring, even after the cup is full, until the professor cries out, “The cup is overflowing.” The Zen master calmly says, “So is your mind with ideas about Zen. How can I teach you when your mind is so full?”

And yet preparation also entails reading the literature of death, dying, and reincarnation. You are going to discover what happens after death. The literature tells you about other people's intuitions—it provides you with useful hints. But you must remember the lesson of the story above. You must be careful not to make what you read part of your belief system.

What we normally call dying of old age is actually death from some illness or other. As the physician/author Sherwin Nuland says, death is painful and grubby. Preparation means that you strive to make your death a creative experience, a death with dignity. It is also a letting go.

The truth is, you are already that which you seek—the immortal one and original consciousness. What you are looking for is the one that is looking. But in the process of looking, there is separateness and pain. This separateness dissolves when you don't strive. That's when unconscious processing occurs.

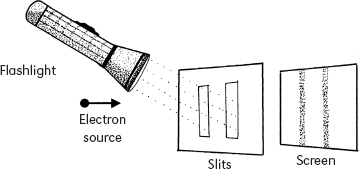

Remember the double-slit experiment? Electrons go through both slits of a two-slitted screen to make a multifringe pattern on the fluorescent plate behind the screen (see chapter 2 and figure 2.1). But this quantum wonder happens only if the electrons are not looked at so they pass through both slits; if you look, there are only two fringes (fig. 10.1) because your looking collapses each electron at only one of the two slits through which it now travels. This is the thing. Striving is always looking. Process, don't look. Unconscious processing lets us accumulate and proliferate ambiguity through the quantum dynamics of the brain-mind/vital-physical bodies.

Fig. 10.1 In an arrangement where a flashlight is aimed at the slits so we can see which slit an electron passes through, the interference pattern disappears and electrons behave like classical, tiny baseballs.

So when pain comes, you may respond to it with both doing and nondoing. Doing means something active, for example, doing some of the practices described below. Nondoing means just that, just letting go—not resisting and not identifying with the pain. The first requires will, the second surrender. This interplay of both may lead to the preconscious encounter, the encounter between your ego and the quantum self, between who you think you are and God.

The filmmaker Mel Brooks said, “If you're alive, you got to flap your arms and legs, you got to jump around a lot, you got to make a lot of noise, because life is the very opposite of death. And therefore, as I see it, if you're quiet you are not living. You've got to be noisy, or at least your thoughts should be noisy and colorful and lively.” In contrast, there is a Zen haiku, “Sitting quietly, doing nothing. The spring comes, and the grass grows by itself.” So the road to the creative encounter combines the wisdom of Mel Brooks and Zen.

You already know about the bardo at the moment of death when you go through an out-of-body experience, take dreamy and visionary trips through the transcendent realms, do a life review, and all that (see chapter 8). The problem is to maintain awareness through it all. It is the perfect balance of doing and nondoing that can take you through it to the clear light.

The Tibetans suggest three practices to help the action-dynamic of the doing/nondoing duo in the creative approach to death.29 These are: the death prayer, which is a practice of devotion; perfect sacrifice, which is a practice of virtue in action; and effortless contemplation, which is the practice of jnana (wisdom/inquiry). Each of these practices is found in many other traditions as well.

In the Tibetan version, the death prayer means praying to Amitabha Buddha while thinking of the Land of Bliss, the Buddhist version of Heaven. This is similar to the last rites in the Catholic tradition, when the priest takes you through a final confession and a prayer to Jesus. Of course, if you make the death prayer your practice for death yoga, you can't wait for the priest to be present every time you do the practice. Similarly, Moslems are told to die saying, “No God but Allah, and Muhammad is the messenger.” Hindus practice japa, meditating internally on a name of God.

When Gandhi was shot, his death prayer was so internalized, he was so ready, that his instant last word was “Ram”—a name of God. The idea of the death prayer is exactly to have this kind of readiness so that the moment of death becomes a true encounter between God and you, your quantum self and you.

How to practice? Create a short mantra for yourself with an archetype of your particular tradition (to which image you are naturally devoted) as the centerpiece of the prayer, and then repeat it at all conscious moments. If it is, “God, I surrender to you,” then you are saying that in your mind whenever you are aware. Pain comes. “God, I surrender to you.” You doze off. You wake, “God, I surrender to you.” Distraction comes. You become aware that you are distracted, “God, I surrender to you.” After you do this a while, the prayer will internalize; it will go on by itself as unconscious processing. You have now reached the perfect balance of doing and nondoing. The Hindus call this ajapa-japa (japa without japa).

What happens? All traditions claim that this prayer practice enables you to recognize consciousness in its suchness (the clear light of the Tibetan Book of the Dead).

The second practice, perfect sacrifice, is the practice of one of the highest ideals in spiritual traditions. It is based on the intuition that voluntary sacrifice is a highly efficacious way to arrive at the nature of truth. Jesus chose crucifixion to redeem humanity, and in the process he himself arrived at resurrection. Buddhists call this the bodhisattva practice, to sacrifice even one's own liberation until all beings are liberated. The Bhagavad Gita talks about tyaga, sacrifice, as the highest practice; it is the theme of the Gita's last chapter, “The Yoga of Liberation.”

So, instead of looking at pain and suffering and recoiling from them, we embrace pain and suffering to relieve not my pain but the pain of humanity.

How to do this practice? If you are going through a particular suffering (not uncommon for people who know they are going to die), imagine that you have taken on this suffering for the sake of others. If you are not suffering from anything in particular, you can imagine taking on a particular suffering for the sake of others. Feel the joy of those who would be relieved from this particular suffering. Coordinate your breath: as you breathe in, take on the suffering of all beings; as you breathe out, send the happiness of release to all beings. Again, you cannot do this by striving alone; you will need to arrive at a balance of will and surrender.

Why does this practice work? You can see that it is akin to bhakti yoga with a touch of karma yoga (see chapter 9). Ordinarily, in our ego we are solipsistic—we literally think or behave as if we are the center of the universe and all else is real only to the extent that we relate to it. From this state, it is impossible to sacrifice for anybody unless we “love” them. I love my spouse, my children, my country, so I can sacrifice for these entities. The practice of sacrificing for others leads to the discovery of the otherness of others, which is the discovery of true love—love that is not conditional on the other being related to me or being my extension. The more you find that you can love others, the less is the dominion of your ego over you. If you can truly die to relieve others' suffering and to bring them joy, you have transcended the self-imposed boundaries of the ego and clearly have entitled yourself to see the light of consciousness.

The psychiatrist Stan Grof has inadvertently discovered a wonderful and effective method for this practice—holotropic breathing, breathing that literally leads to more holistic identification. Initially, when Grof first administered this practice to his clients, they were going through what seemed to be prenatal and perinatal experiences in the birth canal. But as people went deeper, the experiences that came up involved collective pain, the suffering of the whole of humanity. Read, in particular, the experience of the philosopher Christopher Bache with this technique; you will see its power (Grof 1998; Bache 2000).

The jnana path discussed in the last chapter can be used, but this way of developing effortless contemplation is said to be the most difficult—it is to discover consciousness by staying within its nature, within the present moment, without allowing distraction. This is the true meaning of the phrase “conscious dying.”

“Of all mindfulness meditations,” said the Buddha in the Parinirvana Sutra, “that on death is supreme.” In practice, however, only people who are already practicing meditators, who can hold attention for prolonged periods of time, can expect to stay with all the pain, all the suffering, all the distraction, all the grubbiness that death usually involves.

On the other hand, there is the following anecdote about a sage named Tukaram in India. A disciple inquired of Tukaram about how his transformation came, how he never got angry, how he was always loving, and so forth; he wanted to know Tukaram's “secret.”

“I don't know what I can tell you about my secret,” said Tukaram, “but I know your secret.”

“And what secret is that?” the disciple asked curiously.

“You are going to die in a week,” said Tukaram gravely.

Since Tukaram was a great sage, the disciple took his words seriously. During the next week, he cleaned up his act. He treated his family and friends lovingly. He meditated and prayed. He did everything he could in preparation for his death.

On the seventh day, he lay down on his bed, feeling weak, and sent for Tukaram. “Bless me, sage, I'm dying,” he said.

“My blessing is always with you,” said the sage, “but tell me how you've been spending the last week? Have you been angry with your family and friends?”

“Of course not. I had only seven days to love them. So that's what I did. I loved them intensely,” said the disciple.

“Now you know my secret,” exclaimed the sage. “I know that I can die at any time. So I am always loving to all my relationships.”

Just so, the special leverage that the dying situation gives you is intensity—the most essential component of concentration.

Effortless contemplation of the nature of reality is not thinking, but paradoxically it is transcending thinking via thinking. Franklin Merrell-Wolff said, “Substantiality is inversely proportional to ponderability.” The more substantial your contemplation of reality becomes, the less ponderable it is. And the less ponderable it is, the less effort is required. Finally, a stage comes when you realize that, as Ramana Maharshi often reminded people, “Your effort is the bondage.” When effort blends with surrender, everything becomes effortless—sahaj in Sanskrit.

When contemplation becomes substantial and imponderable and no effort is needed, you are in the natural flow of consciousness—sahaj samadhi. As Bokar Rinpoche says, “When death finally comes, if the practitioner remains in the nature of the mind [consciousness], he or she will obtain full awakening and become a Buddha at the stage called the absolute body or clear light of the moment of death.”

There is a great story in the Upanishads. There was a young boy, Nachiketa, whose father arranged a great yajna (Sanskrit word meaning sacrificial ritual) of sacrifice, a giveaway orgy, to assure his place in Heaven. But the father was calculating; for example, he kept the best cows for himself, giving away the weak ones. Nachiketa, noticing his father's halfhearted giving, challenged him. “Father, to whom are you giving me?” No answer. But Nachiketa persisted. When he asked the third time, the father angrily replied, “Yama, the death god. I've decided to give you to the death god.”

But a promise is a promise, so Nachiketa went to the abode of Yama. Since he was premature, nobody was there to receive him. Nachiketa waited for three nights after which the death god returned. Yama was embarrassed that a guest had been ignored for three nights, and to make up for it, he granted Nachiketa three boons.

The first two boons were trivial, but for the third boon, Nachiketa wanted to know the secret of death—what happens after death? “Some say we die, some say we don't. What really happens?”

Now Yama was in a bind and tried to bribe himself out of giving away the secret of death. But nothing doing. So finally, he taught Nachiketa the truth about existence—consciousness does not die with death. Realizing this truth within oneself, said Yama, one learns the mystery of death.

It happens. Ramana Maharshi was sixteen when one day he had the strange feeling that he was going to die and “a violent fear of death overtook me.” He began thinking what to do about death. What does death mean? What is it that is dying? He also began dramatizing the coming of death. He stretched out stiff, as though rigor mortis had set in, imitating a corpse. And he thought to himself, “Now that this body is dead, with the death of this body, am I dead? Is the body I?” The force of his inquiry precipitated an unexpected transformation in being. Later he wrote:

It flashed through me vividly as living truth that I perceived directly, almost without thought process. “I” was something very real, the only real thing about my present state, and all the conscious activity connected with my body was centered on that “I.” From that point onwards the “I” or Self focused attention on Itself by a powerful fascination. Fear of death had vanished. Absorption in the Self continued unbroken from that time on. Whether the body was engaged in talking, reading, or anything else, I was still centered on “I” (Quoted in Osborne 1995).

29I had much help from the spiritual teacher Joel Morwood in writing this section.