bar 4

Blues Feelings and “Real Bluesmen”

THE AUDIBLE RESIDUE OF TRANSGENERATIONAL STRUGGLES

By this point, I presume, you’ve got a working sense of the ideological struggle that governs contemporary blues talk and a somewhat more nuanced sense of the music’s sociohistorical origins and aesthetic strategies. Before we move ahead into a counterstatement of sorts, I’d like very briefly to recapitulate. (The twelve-bar blues structure is characterized by both repetition and inflection points—i.e., chord changes. Bar 4, the first such inflection point, is always characterized by a feeling of incipient change.)

I began by framing contemporary blues talk as a struggle between two polarized positions. The first, black bluesism, insists that blues is, or should be, a black thing. White blues audiences are acceptable although not ideal; white blues performers (and especially singers) are deeply problematic, at once aesthetically inadequate and unconsciously beholden to blackface minstrelsy; whites who seek to profit from, speak with presumed authority about, or in any other way make possessive claims on the music are inflictors of the blues rather than legitimate claimants, and thus aligned with the slave owners, bossmen, and unscrupulous record label owners of yore.

The other position, blues universalism, acknowledges that a great preponderance, if not quite all, of the past masters of the music were black, but it also celebrates white inheritors, a select set of what might be called white blues greats. More important, it views blues music and contemporary blues culture as an inspiring democratic melting pot, a healing cauldron in which blacks and whites and everybody else who plays and grooves to the music is, or should be, judged not by the color of their skin but by the content of their musical character. Blues, in this case, becomes a shared subcultural endeavor with an antiracist sense of purpose.1 The shared sense of purpose among black and white musicians is understood, moreover, to have a fugitive history tracing back to the days of Jim Crow. David Honeyboy Edwards speaks in his autobiography about Harmonica Frank Floyd, a white Mississippi-born blues musician with whom he traveled and worked in the 1920s and ’30s. “Musicians was just musicians back then, it didn’t have nothing to do with black or white,” Honeyboy insisted. “We was all glad just to see each other. We made music together.”2 Blues universalism views black bluesist race-talk as hurtful, a needless stirring up of trouble in the face of so much good news.

One problem with the blues universalist position is that such scenes of musical brotherhood are situated within a political economy in which white people have more economic and institutional power.3 This power differential was certainly operative in the early days of the race records industry, as Karl Hagstrom Miller argues in Segregating Sound: Inventing Folk and Pop Music in the Age of Jim Crow (2010), and as August Wilson dramatizes in the figures of Sturdyvant and Irvin, and in some ways it’s even more noticeable today, in the aftermath of the white blues eruption of the 1960s. In Gramscian terms, whites have achieved something close to hegemony. With few exceptions, they run the festivals, record labels, clubs, museums, cruises, and booking agencies; they dominate the blues societies, radio shows, instructional websites, and audiences. Not surprisingly, white ideas about, and tastes in, blues tend to dominate the mainstream market—if not, importantly, the much smaller soul-blues market. African American artists know this. Some resent the situation; some make the necessary adjustments and profit from it.4 A black bluesist might argue, for example, that Honeyboy’s autobiographical cowriters, Janis Martinson and Michael Frank, are both white; that Frank was his longtime manager as well as harmonica accompanist at the time; that Honeyboy’s contemporary audience is overwhelmingly white; and that his fond memories of Harmonica Frank Floyd may contain an element of calculated self-interest, abetted by the editorial interventions of his white handlers.

When cultural politics enter the picture, contemporary conversations about the music trend rather quickly toward either black bluesism or blues universalism. Both extremes tend to shy away from the paradoxes that would call their certainties into question. It would seem hard to argue, for example, with the claim that the blues, understood both historically and experientially, come from somewhere—specifically, the difficult material and social conditions that confronted working-class African American musicians in the Jim Crow South. Yet even that “from” is, at least potentially, a bone of contention. Some commentators on the black bluesist side of the divide argue for a longer horizon; they view the blues as the audible residue of transgenerational black struggles that extend back beyond the Civil War into the slave past. Yet many black commentators, as I’ve noted, distinguish the pressured freedom of Jim Crow from the manifest unfreedom of slavery in an effort to explain the difference, the novelty, of blues song. Theologian James H. Cone argues for that position in The Spirituals and the Blues. “Despite the fact that the blues and the spirituals partake of the same black experience,” he writes,

there are important differences between them. The spirituals are slave songs, and they deal with historical realities that are pre–Civil War. They were created and sung by the group. The blues, while having some pre–Civil War roots, are essentially post–Civil War in consciousness. They reflect experiences that issued from Emancipation, the Reconstruction Period, and segregation laws. … Also, in contrast to the group singing of the spirituals, the blues are intensely personal and individualistic.5

Although Cone distinguishes the blues from slave songs both formally (i.e., solo singing versus group compositions) and experientially (i.e., post-Emancipation experience versus pre–Civil War experience), he also reinforces the idea that experience, black experience, is the key constitutive element of the music. Until recently, most people would have considered this claim uncontroversial, especially if what was being discussed was blues music created during the first half of the twentieth century. Aren’t the blues, at bottom, a sort of collective black feeling of suffering, of beleaguerment, in the face of white racist violence and exploitation in the Deep South? When contemporary black commentators like Corey Harris insist, in the face of the white blues onslaught, that blues is black music, with that specific and audible emphasis on the word “black,” their claim is founded, among other things, on a familiar declension: blues isn’t just a musical form, a set of lyrics and sounds and instrumental techniques that anybody can master, and it isn’t just a feeling. It’s a specifically racial feeling, one grounded in the painful particulars of the black experience. Since whites don’t share that experience, either historically or existentially (i.e., in the present day), they can’t possibly play the music for real. They’re just appropriating, mimicking, pretending.

BLUESMEN AND SONGSTERS

Regardless of how far back one sources the music or what one thinks about white blues musicians as a group, it would seem hard to argue with the baseline claim that there’s some connection between blues music and the multiple stresses of black life under Jim Crow. But that is precisely what Elijah Wald does in his paradigm-shifting study, Escaping the Delta: Robert Johnson and the Invention of the Blues (2004). Wald doesn’t deny racism. He readily admits that the world in which blues music was popular was a world in which African Americans were terrifically oppressed. He just doesn’t believe that that oppression had much to do with the reasons why black people sang, played, recorded, and—above all—purchased and listened to the blues. In this respect, he is arguing against one of the central claims I offered in my own academic study, Seems Like Murder Here: Southern Violence and the Blues Tradition (2002), which is that the blues tradition, both musical and literary, is marked in various ways by anxiety, grief, and rage bred by lynching and other forms of disciplinary violence.

Before digging more deeply into the debate, I should note that Wald and I are both white blues musicians who spent a lot of time working side by side with gifted and charismatic older African American performers, and our ideas about the music have been strongly inflected by that experience. My partner and guide was Sterling “Mr. Satan” Magee, a Harlem-based guitarist and singer who hailed from Mt. Olive, Mississippi. Wald worked with Howard “Louie Bluie” Armstrong, a string-band musician from Tennessee who played fiddle and mandolin. Many people would call Armstrong a songster, not a bluesman, somebody who played a wide range of folk, jazz, and popular material, and here it is worth pausing to clarify an issue that will become important in a moment.

When most people use the word “bluesman,” they use it not just as a way of objectively describing the repertoire that a given musician performed and recorded but as a term of high praise, a marker of authenticity: a “real bluesman.” The irony is that no term has less relevance to the lives that African American blues performers in the prewar South actually lived. The term “bluesman” is the creation not of black blues performers but of white folklorists and journalists. The term appears in print very sporadically prior to the early 1960s; the online Oxford English Dictionary offers two early journalistic uses of the unhyphenated “blues man,” one each in 1930 and 1953, both of which refer to white jazz clarinetists (Ted Lewis and Mezz Mezzrow) and seem edged with gentle mockery, as though commenting on a fad.6 In 1961, folklorist Mimi Clar and D. K. Wilgus, the record review editor of the Journal of American Folklore, use the terms “blues men” and “bluesmen,” respectively, when discussing recently issued recordings by African American blues performers.7 The publication of foundational studies by Charters (1959) and Oliver (1960), along with the emergence of the folk revival and the rediscovery of older black southern recording artists, including Son House, Mississippi John Hurt, and Skip James, seems to have given currency to the term, but it also introduced a complication: by 1965, Wilgus is invoking “the new distinction between ‘songster’ and ‘bluesman.’”8 The distinction is an academic one, quite literally. Prior to the intervention of white folklorists, the word “songster,” along with the words “musicianer” and “musical physicianer,” were what people in black communities called traveling musicians who performed blues and other popular material; white journalists and record collectors tended to just call them blues singers. Folklorists, concerned with delineating and preserving black folk communities and disconcerted by the recent emergence of a white blues “thing,” wanted to distinguish between what they took to be two different sorts of black male blues performers of acoustic or “country” blues: those whose repertoires, especially on record, seemed to consist primarily of blues songs, and those whose repertoires included a broad range of nonblues material, much of it oriented toward white audiences as well as black ones. They called the former bluesmen, the latter songsters. Son House was a bluesman; Mississippi John Hurt was a songster. The bluesmen, to these folklorists and the journalists who took cues from them, were the hardcore, defined by terms of critical approbation like “raw,” “impassioned,” and “authentic”; the songsters were … songsters. Hurt was “gentle,” “soft-spoken,” and “soothing.”9 Bluesmen were the presumptive carriers of race-wide pain—“the conscience of the Delta,” in the words used by ethnomusicologist David Evans to describe Charley Patton.10 Songsters were something less than that.

Bluesmen and songsters. It’s a false distinction, based on a significant misunderstanding, and it’s a falsehood that Wald skewers in a chapter in Escaping the Delta called “What the Records Missed.” Our foundational error, according to Wald, is to imagine that we can accurately assess what blues performers like Honeyboy Edwards, Robert Johnson, and Muddy Waters played live by looking at their recorded repertoires. But we can’t. The reason this assumption would be mistaken has something to do with racism in the music industry, a lot to do with racism in the Jim Crow South, and everything to do with the fact that juke boxes—which spun 78 rpm records and provided music without live musicians—didn’t really enter the southern scene in a big way until the late 1930s. If you were a black folk musician who wanted to make a living prior to the jukebox era, and even after jukeboxes were introduced, you had to act like what we might now retroactively call a human jukebox. You needed a wide range of material that you could pull out of the hat on a moment’s notice, whatever the public requested. You needed current hits, regardless of the idiom, along with old favorites, and you needed to minister to white as well as black audiences. That’s how you made enough nickels and dimes to stay out of the white folks’ fields. It turns out that Edwards, Johnson, Waters, and their peers had much broader performing repertoires than they were actually permitted to record. When Muddy was interviewed by Alan Lomax in the early 1940s, he listed a half-dozen Gene Autry songs in his repertoire.11 Johnson, according to his traveling companion Johnny Shines, “did anything that he heard over the radio” but was especially fond of polkas. (“Polka hound” was Shines’s term.)12 “Overall,” Wald writes of those players and others of their ilk, “it is probably true that no one outside vaudeville made a living during this period as purely a ‘blues’ player. All were dance players, party players, street-corner players—songsters and musicianers, if you will—who included blues because it was one of the hot sounds of their time.”13 As a consequence, the repertoires of these so-called bluesmen and their white peers in the South overlapped to a considerable degree, which is to say that both cohorts drew on a common stock of songs, both old and new. The black musicians didn’t just play blues or “black music,” in other words, and the hillbilly players didn’t just play old-timey or “white music.” The situation on the ground was much more hybrid than that.

But, as Miller articulates in Segregating Sound, racism in the recording industry worked hard to clarify—which to say, racialize—the situation. In essence, the industry put all southern musicians through a racial sorting process. Talent scouts told the black musicians, “You will be permitted to record race records,” which meant blues. They told the hillbilly musicians, “You will be permitted to record old-timey, mountain, vaudeville, and novelty numbers.” Some white musicians of the period, most notably Jimmie Rodgers, recorded blues as well (“Blue Yodel No. 1”), but they were sold as hillbilly records rather than race records. Just as important, gatekeepers to the blues recording industry like H. C. Spier of Jackson, Mississippi, insisted that the black musicians perform their own original tunes, not covers of current pop songs, in part to feed the “hot” race records market and in part to avoid paying the statutory royalties that pop covers would have required. Faced with this situation, songsters like Edwards, Johnson, and Waters set aside the full spectrum of songs and idioms through which they’d been expressing themselves and making a living—“ragtime, pop tunes, waltz numbers, polkas,” in Johnson’s case—and said, in effect, “Okay boss, since blues are what you want, I’ll give you blues.” They narrowed their focus and remanufactured themselves as bluesmen, although that specific term didn’t exist at the time.

What has been handed down to us as a result is this idea that blues artists, “real bluesmen,” just play pure, dark, down-home blues in which the soul-deep ache of an oppressed race finds expression. Nothing could be further from the truth. Almost all of the prewar blues artists played, and expressed themselves through, a much wider range of material than that—material that spoke to a world of experience beyond the blues conditions and blues feelings that I’ve been exploring thus far. If we know that Johnson’s favorite performance pieces, apart from polkas, included “Yes, Sir, That’s My Baby,” “My Blue Heaven,” and “Tumbling Tumbleweeds,” that tends to undercut not just the idea of Johnson as a tortured genius obsessed with the devil but also the larger idea of the black southern bluesman as a musical mechanism for bodying forth the cry of an oppressed people.14 The revisionist arguments offered by Wald and Miller profoundly destabilize both ideas.

RETHINKING “REAL BLUES”

Wald’s revisionism is enabled by a specific definitional decision that he introduces early in his study and that turns out to have enormous implications. His working definition of blues, he says, will be “whatever the mass of black record buyers called ‘blues’ in any period.”15 This seemingly innocuous move accomplishes several things. One thing it does is completely separate blues music from any necessary connection to oppressive conditions and bruised feelings. Instead, it insists that blues is pop music: music that sells a lot, charts well, and compels the interest of the widest possible swath (the “mass”) of the black record-buying public. A second thing that happens when you shift the definitional focus from the harsh world out of which the music emerged to the tastes of the black audience that helped determine the market for the music is that the “deep blues” of Charley Patton, Son House, Robert Johnson, and other Delta legends is suddenly decentered in favor of … what? Well, the recordings that a nationwide audience of black music consumers actually purchased, rather than the Delta blues stuff that never caught their fancy. W. C. Handy and his compositions, especially “St. Louis Blues,” take center stage in the 1910s, not Henry Sloan and other country blues precursors. Bessie Smith, Ma Rainey, and the other blues queens dominate the 1920s, since they were, as theater historian Paige McGinley argues in Staging the Blues: From Tent Shows to Tourism (2014), the first blues performers who actually became pop stars; they literally defined the word “blues” as an American show-business concept at a time when Patton and House were strictly local celebrities.16 In the 1930s, crucially, an urbane singer and pianist named Leroy Carr becomes for Wald the paradigm of a blues recording star, waxing several hundred recordings, including “How Long, How Long Blues.” Carr not only outsold Robert Johnson by a hundredfold or more, but he also was remembered decades later by aging black listeners who had no idea who Johnson was.

Why don’t we—meaning contemporary blues fans, black and white alike—know as much about Carr as we know about Johnson? According to Wald, it’s because the story of the blues has for a long time been told by white writers invested in what historians would call a presentist narrative line. Seeking a blues genealogy for aging rock-blues superstars like Eric Clapton, the Rolling Stones, and Led Zeppelin, the baby boomer blues story anchors itself in what it imagines to be the autochthonous brilliance and gothic atmospherics of a Delta primitive like Johnson, neglecting the fact that Johnson’s recordings barely registered with the nation’s black record-buying public. Carr and the blues women, by contrast, although immensely popular with black audiences during their lifetimes and beyond, offer no anchoring mythology for rock’s grand narrative, no shared aesthetic strategies or thematic concerns—except perhaps when Janis Joplin is viewed as an update on Big Mama Thornton. When the blues story is told as essentially the run-in to rock, what gets erased is a radically different and in some ways much truer history in which the tastes of “the mass of black record buyers” are tracked from the 1910s right up into the present day, bypassing rock entirely to focus on black blues and soul-blues artists like Willie Clayton, Ms. Jody, Sir Charles Jones, Denise LaSalle, Bobby Rush, Johnnie Taylor, and Dinah Washington. In this respect, at least, Wald’s intervention serves the black bluesist cause by forcing white blues lovers to acknowledge the self-serving way they’ve distorted the music’s history even while pretending to honor it.

Wald isn’t content, however, just to shift the center of gravity from what he sees as the overvalued stock of Robert Johnson to the undervalued stock of Leroy Carr. He insists, incredibly, that Johnson is irrelevant to the course of blues history—at least when blues is defined in terms of black pop-musical tastes. In the face of the mass of white blues musicians, journalists, scholars, and fans who consider Johnson to be a central figure, one who anchors the tradition, Wald suggests “that Johnson was nothing of the kind, and that as far as blues history goes, he was essentially a nonentity.”17 This is no more than a half-truth; if nothing else, Johnson remained an important influence on Muddy Waters, and Muddy had a fair number of hits on the R&B charts. But the half-truth it contains is potent: neither Johnson nor his songs achieved the slightest visibility, on a national level, with the black record-buying public of his time. Compared to a hundred other blues artists, from Leroy Carr to Bessie Smith, from Lonnie Johnson to Walter Davis, Robert Johnson was, in fact, a nonentity. He wasn’t “hot.” He wasn’t even warm. His form of solo guitar-based blues wasn’t at all what the black record-buying public wanted in the late 1930s. If we—today’s imputed white blues-consuming public—think of Johnson as important, Wald argues, that’s because he’s important to Eric Clapton and Keith Richards and other boomers who were introduced to him on record in the early 1960s as a disembodied phantasm, a “legend” to whom few biographical facts were ascribed and whose Faustian myth and tragic death made him impossibly attractive as a precursor figure for a rock-blues lineage of bad boys.

There is something elegant, logical, and compelling about defining blues as “whatever the mass of black record buyers called ‘blues’ in any period.” It certainly seems at first blush like a gesture designed to rescue the blues tradition from the distortions accrued during the decades of white ascendance. But Wald’s revisionist move has unforeseen consequences. One problem surfaces when we imagine somebody making the same claim with regard to literature: that the really important and representative stuff, finally, is the stuff that shows up on the best-seller lists. The bestselling novels of 1930 were Cimarron by Edna Ferber and Exile by Warwick Deeping; a relative unknown named William Faulkner also published a novel that year.18 As I Lay Dying sold poorly and was soon forgotten—until, fifteen years later, a literary critic named Malcolm Cowley published The Portable Faulkner and people began to pay attention. Today, Faulkner is the canonical figure, the conscience of his era, and Ferber and Deeping are all but forgotten. Isn’t it possible that in recuperating and celebrating Robert Johnson, the white blues audience, like Cowley with Faulkner, rescued a neglected genius from the unwarranted obscurity to which mercurial black popular tastes had consigned him? Although mass popularity can be an index of what is on people’s minds, the category of “unpopular” often turns out to contain artists—Henry David Thoreau and Herman Melville, for example—who are speaking complex, uncomfortable truths about their own historical moments that the popular audience isn’t prepared to hear. Maybe “Hell Hound on My Trail” was too much of a downer for a black public that preferred lighter, more danceable fare. And maybe it’s a good thing that Clapton and Richards were electrified by it.

There’s no reason to assume, in other words, that the white blues audience’s extraordinarily high valuation of Robert Johnson is misplaced. But Wald’s claims might lead us to think twice before saying, in effect, “I’m going to anchor my ideas about the blues in a specific group of rural artists”—the Mississippi Delta bluesmen—“whose recordings sold very poorly to black consumers.” Why not begin with the early blues artists whose recordings black consumers actually bought in large quantities? When you do this, you’re forced to say, “Well, the women blues singers were really important.” They sold really well in the 1920s, and their performances garnered infinitely more attention in the popular press than the Delta bluesmen. And here Wald confronts us with another paradox, one that pressures our residual desire, whoever we are, to locate the “real blues” in those black male bluesmen. We are inclined to think, because the story has so often been told this way, that the country blues predate the city blues—that the blues “come from the cotton fields,” as the saying goes—and, consequently, that the country bluesmen inaugurate a rough-hewn tradition that the classic blueswomen appropriate, gussy up, theatricalize, and render less authentic. This story gains apparent explanatory power from several factors, including the fact that the classic blueswomen like Ma Rainey and Bessie Smith traveled in posh Pullman coaches rather than hitchhiking along gravel highways and the fact that Tin Pan Alley songwriters, ambitious and urbane black men, composed many of the songs these blueswomen performed and recorded. The bluesmen were rural primitives, the classic blueswomen were urban professionals; the latter capitalized on the music of the former. That’s how the story goes. But the story, or at least the second half of the story, is wrong—or so Wald argues.

Although African American blueswomen first debuted on record in 1920, with Mamie Smith’s epochal “Crazy Blues” (authored by Perry Bradford), it turns out that they had a significant prehistory in the Mississippi Delta during the preceding decade. This is the revelation offered by archival historians Lynn Abbott and Doug Seroff in Ragged but Right: Black Traveling Shows, “Coon Songs,” and the Dark Pathway to Blues and Jazz (2007). The Delta, it turns out, was overrun at harvesttime with black minstrel troupes and tent shows featuring “Southern coon shouters” and “up-to-date coon shouters,” the then-current terms of art for Rainey, Smith, Lizzie Miles, and other soon-to-be recorded blues stars. “Eighteen shows have made Clarksdale in the past month,” wrote an entertainment reporter in 1917, as the cotton harvest came in. “And still they come to Mississippi.”19 The word “blues,” we know, was just beginning to develop a pop-musical valence during those years in the aftermath of W. C. Handy’s “St. Louis Blues” (1914) and “Hesitating Blues” (1915). Rainey and Smith weren’t yet called blues singers, but they sang songs called blues—and they did so with a power and polish, backed by jazzy horn-and-rhythm ensembles, that mightily impressed the rural Mississippi audiences who had paid a nickel or a dime to see their show. Charley Patton, Son House, and other future legends of the Delta blues were a part of that audience, and, argues Wald, they were paying attention. Those men as yet had no name for the little cotton field ditties and “jump ups” they’d been evolving with the help of steel-stringed guitar and slides, but there is every reason to think—or so insists Wald—that the tent-show women, blues singers before the term existed, helped them shape and name their own new acoustic music. So if you thought that blues starts in the country and then migrates to the city: not so fast! The city—Bessie and Ma out of Chattanooga and Atlanta—came to the country, and the country took notes. After the tent shows had packed up and left the Delta for the winter, a musician who could flavor his guitar and vocal stylings in a way that evoked the blueswomen and their flashy repertoire stood a better chance of attracting a paying audience.

It is at this point, I suggest, that we might begin to glimpse common ground between Wald’s blues-as-pop-music perspective and my own claims about the way the blues tradition is marked by anxieties about white mob violence and disciplinary encirclement. Why might have the Delta bluesmen, and Robert Johnson in particular, have been so interested in where the cutting edge was, stylistically speaking? Because the cotton fields were right there, offering their specter of hard, exploitative labor backed up by vagrancy law and lynch law, and that was your fate unless you found another way to get by. Any freedom worth having was premised on economic freedom; knowing how to satisfy your audience, knowing what was “hot” and getting at least a little of that into your repertoire, was the traveling musician’s escape route. This is why the “bluesmen” weren’t bluesmen at all but songsters, musicianers, jacks-of-all-trades. They were skilled musical artisans, rambling tradesmen with guitars. They aimed to please the people, by any means necessary. And the people were pleased. The women in particular, according to Honeyboy Edwards, were so pleased that a traveling musicianer could have his pick.20

Where, amid all this pleasure and careerism, is the suffering out of which the blues were supposedly born? A central paradox of the blues lies in the tension between what Wald rightly calls the “up-to-date power and promise” that attracted black listeners to the music and what he dismisses as the “folkloric melancholy” lingering behind the music, the “heart-cry of a suffering people” that, he argues, just doesn’t have much to do with why black record buyers made the choices they did.21 That heart-cry, that blues feeling, is, for contemporary exponents of the black bluesist position such as Sugar Blue, the whole point. It’s the transgenerational inheritance voiced by the music, a collective race memory that contemporary white investments in the music threaten to obliterate. “This is a part of my heritage in which I have great pride,” Blue told a crowd of scholars, musicians, and aficionados at the 2012 “Blues and the Spirit” symposium at Dominican University near Chicago.

Paid for in the blood that whips, guns, knives, chains and branding irons ripped from the bodies of my ancestors as they fought to survive the daily tyrannies in the land of the free, where some men were at liberty to murder, rape, and lay claim to all and any they desired. From this crucible, the blues was born, screaming to the heavens that I will be free, I will be me. You cannot and will not take this music, this tradition, this bequest, this cry of freedom and dignity from bloodied, unbowed heads without a struggle as fierce as the one that brought us in chains of iron beneath the putrid decks of wooden ships to toil in pain but not in vain.22

Sugar Blue (born James Whiting in Harlem, N.Y.) is uninterested in the sorts of arguments tendered by African American scholars such as Cone, Davis, and Salaam about why blues music stands apart, formally and thematically, from the music of the slavery era. Instead, he sources the blues in a continuing narrative of brutally compelled black labor, one that at some indeterminate moment provoked the birth of a prophetic musical scream or cry—freedom-seeking, individualized, a mode of resistance that conferred personhood. The invidious “you” he indicts is, it would seem, the whole white blues “thing”: not just his white musical peers (whom he may not even consider his peers, since the oppressive history he invokes isn’t theirs to claim) and a million lesser talents but the white-dominated superstructure of the mainstream blues world—DJs, clubs, festivals, magazines, societies, museums, instructional websites, advocacy organizations, and awards ceremonies. Scholarship, too, perhaps.

Sugar Blue’s conception of the blues as an ancestral inheritance, an inalienable black cry tracing back to slavery, is echoed in a 2019 interview by Pulitzer Prize–winning black poet Tyehimba Jess, author of leadbelly (2005):

You’re talking about a sound that came directly out of slavery getting directly transported from the continent, laboring under the duress of loss of language, not being able to speak your language upon punishment of death, not being able to learn how to spell or read and write in the language of your captor. Not being able to do that, and then not being able to own yourself or any of the things produced from your labor, or even the things you produced from yourself—your children. Or any of the things that produced you; your mother and father are taken away from you. The only thing you actually do have that they can’t touch is what comes out of you—and that is the blues, that is the sound of the blues. So you sing the sound that is labored underneath all of that tension, has been shaped by that tension. … So when you’re talking about the blues, that is what you’re talking about.23

Perhaps because his forum is the literary world, where he has essentially no white peers seeking to fill the role of blues poet, rather than the mainstream blues scene, where any number of white blues harmonica players are jostling with Sugar Blue for available gigs, Jess’s heritage claim is animated by far less frustration and aggression than Blue’s. “[The blues] still manifests on the technical level in playing the instruments,” Jess says, praising a recent performance by Billy Branch,

but I think, in a lot of ways, you want to talk about ownership by the people who created it. Literature is where you find the real ripple effect of the blues the strongest. The most impermeable. Because it’s directly out of the black experience. … Other people will be able to practice the blues. But it generated from us, and the most direct experience of it is coming through other art forms. The one I know best is literature.24

The word “practice” signifies on and delegitimizes white (indeed, any non–African American) blues musical performance. But Jess also defends the black blues, as a larger project, by decentering blues music: insisting that the ancestral inheritance and its resonance in contemporary black experience can’t be endangered, no matter how many whites play the music, because “the sound of the blues” lives on in the poems he writes.

Jess has a luxury, in a sense, that Blue, Branch, and other black blues musicians on the mainstream scene don’t have: freedom from direct competition. This can help explain why the words “fierce” and “struggle” rip out through the belly of Blue’s manifesto. Sidestepping the paradoxes and complexities of lived historical experience explored by Wald and others, including Robert Johnson’s fondness for polkas and the wholesale abandonment of blues music in favor of soul music by black youth during the 1960s, Blue evokes the blues less as music than as the purest and most hard-won sort of feeling, a racial and ancestral feeling carried by the music, whose continuance is profoundly endangered by the present state of affairs.

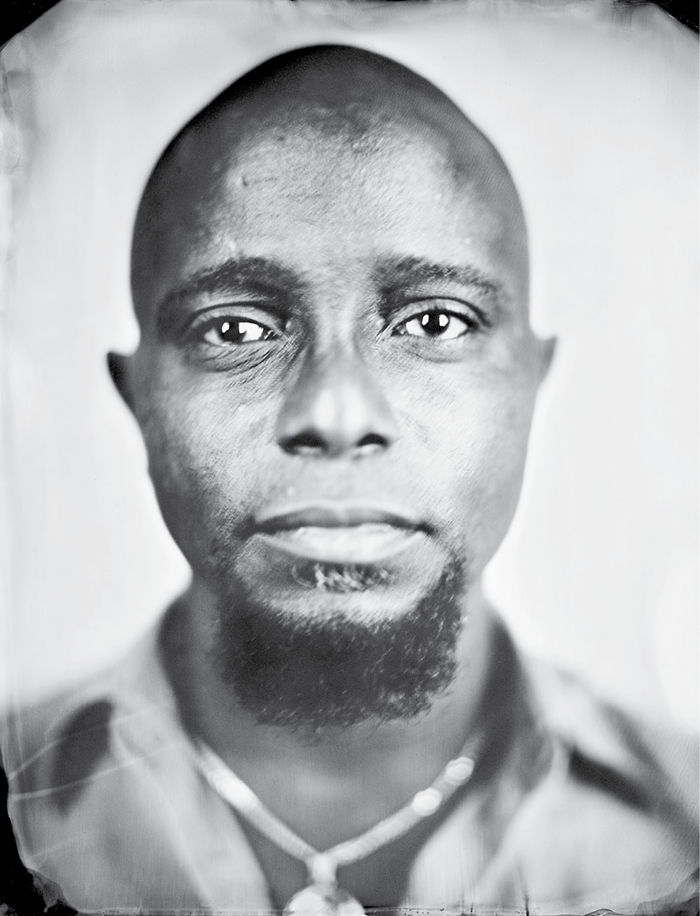

Tyehimba Jess

(courtesy of the photographer, Keliy Anderson-Staley)

Whatever objections one might raise, one is forced to say: here is a distinctly contemporary evocation of blues feeling, this mixture of pain, pride, and outrage felt by an African American musician seeking to reclaim a cherished inheritance from the predations of the contemporary blues world. One might go a step further than that, in fact, and view Blue’s and Corey Harris’s aggressive pushback against white-dominated blues-business-as-usual as a cultural development that parallels the political advocacy of Black Lives Matter: new black consciousness demanding, in no uncertain terms, that a palpably unjust situation—at least in the eyes of those who so adjudge it—be rectified in a way that acknowledges the continuing precarity of black life.

We have the grounds for a worthy debate here. Although I view Blue’s totalizing claims as a kind of mythmaking rather than a properly historical argument, mythmaking—personalizing and enlarging grievance to epic dimensions—is an essential constituent of the blues tradition, as the names Howlin’ Wolf and “the Devil’s Son-in-Law” suggest. Blue’s statement speaks powerfully, in any case, to two key concerns that animated African American blues performers in the Jim Crow South: economic exploitation and disciplinary violence, the latter enforcing the former. In actual practice, the desire to scream, “I will be free, I will be me,” was mediated by a keen sense of self-preservation, since the same vigilante violence that bred terror and resentment could easily jump down on anybody foolish enough to complain about it directly. In 1946, folklorist Alan Lomax sat down with Big Bill Broonzy, Memphis Slim, and Sonny Boy Williamson in a New York City hotel room and got them to speak openly, into his Presto disc recorder, about such matters—a recording issued more than three decades later as Blues in the Mississippi Night. “Tell me what the blues are all about,” he said. And they did. “Here, at last,” he later wrote, “black working class men had talked frankly, sagaciously and with deep resentment about the inequities of the Southern system of racial segregation and exploitation.” Broonzy and Slim both described the practice of signifying: men they knew who wanted to “cuss out the boss,” but, fearful of reprisal, did that indirectly by cursing out a nearby mule or encoding the insults into a work song. “Signifying and getting his revenge through songs,” Slim summed up: that was the southern black man’s strategy. Yet after having unburdened themselves so frankly to Lomax, the three men were terrified when he played back the recording and they begged him never to share it with the public. “If these records came out on us,” they told him, southern whites would “take it out on our folks down home; they’d burn them out and Lord knows what else.”25

The violence was real, the feelings it produced in these bluesmen were urgent and real; both the violence and the feelings shaped the blues tradition in profound ways that dismissive phrases like “folkloric melancholy” don’t do justice to. This is where I part company with Wald and his decision to ground claims about the blues in black popular taste. If Sugar Blue is too quick to totalize the blues, reducing the entire tradition to a freedom-scream paid for in blood, whips, guns, knives, chains, and branding irons, then Wald is too ready to write off any critical concern with the darker blues feelings as a species of white blues romanticism, a projection of an imagined “heart-cry of a suffering people” into a streamlined pop music characterized by professionalism, humor, “up-to-date power and promise.” My own perspective has been shaped by the blues literary tradition, especially autobiographies by Mississippi musicians such as Willie Dixon, Honeyboy Edwards, B. B. King, and Henry Townsend. When I speak about the blues, I am speaking about not just the songs those men recorded but also the life stories they told about the Deep South world in which they came of age, including the emotional scars they bore as a result of that upbringing.

CONFESSING THE BLUES

One thing that became apparent to me as I began to investigate this material is that the autobiographical process offered these men a long-deferred chance to bear witness. The songs they’d recorded as younger men were one way of doing that, perhaps, but their late-life confessions gave them a chance to speak with considerably more frankness about southern blues life than their Jim Crow environs permitted them back in the day. Their confessions were enabled by their knowledge that they were no longer in danger of violent reprisal. Quite the opposite: they were bearing witness into the tape recorders of congenial white ghostwriters who were eager to help them shape those confessions into books that could be shared with an admiring white public of blues fans who, like Lomax, wanted to know where their blues came from.

I termed this form of retrospective witness-bearing “confessing the blues.”26 In Blues All around Me (1996), King offers a remarkable example of this phenomenon, one that supplements his somewhat more circumspect claim in 1986 about how “so many Negroes … had been killed many, many different ways if you said the wrong thing at the wrong time,” that people in Mississippi lived under “fear of the boss,” and that his blues—the blues he sang and played—were prompted by living under that threat of violence.27 It’s crucial to remember that King never directly addresses lynching and other forms of racial violence in his lyrics, with one notable exception: the second verse of “Why I Sing the Blues” (1969), with its invocation of slavery in a first-person voice that stands in for the collective subject of black history:

When I first got the blues

They brought me over on a ship

Men were standing over me

And a lot more with a whip

And everybody wanna know

Why I sing the blues

Well, I’ve been around a long time

Mm, I’ve really paid my dues

But lynching? King never sings of it. Very few blues performers did. There wasn’t much of a market for it. But the musicians certainly knew about lynching, saw its after-effects, avoided its clutches as best they could. They felt it. Its presence in the social field was part of the emotional palette from which many of them were working. King makes this clear by describing his own encounter, as a preteen, with the aftermath of a lynching in Lexington, Mississippi—a legal lynching, in fact, where the body of a young black man who had been hung inside the jail was brought out front for all to see. It was a moment “of shock and pain,” he recalls, “that can’t be erased from my memory”:

A sunny Saturday afternoon and I’m walking to the part of Lexington with the stores and the main square. I’m running an errand for Mama King, feeling the summer heat along my skin, feeling halfway happy. At least there’s no school today. I’m delivering a big basket of rich folks’ clothes Mama King has washed and ironed. Suddenly I see there’s a commotion around the courthouse. Something’s happening that I don’t understand. People crowded around. People creating a buzz. Mainly white folk. I’m curious and want to get closer, but my instinct has me staying away. From the far side of the square, I see them carrying a black body, a man’s body, to the front of the courthouse. A half-dozen white guys are hoisting the body up on a rope hanging from a makeshift platform. Someone cheers. The black body is a dead body. The dead man is young, nineteen or twenty, and his mouth and his eyes are open, his face contorted. It’s horrible to look, but I look anyway. I sneak looks. I hear someone say something about the dead man touching a white woman and how he got what he deserves. Deep inside, I’m hurt, sad, and mad. But I stay silent.

What do I have to say, and who’s going to listen to me? This is another secret matter; my anger is a secret that stays away from the light of day because the square is bright with the smiles of white people passing by as they view the dead man on display. I feel disgust and disgrace and rage and every emotion that makes me cry without tears and scream without sound. I don’t make a sound.28

Here is B. B. King as a black boy in Mississippi, shocked into awareness of his own vulnerability. Even as he is suffused with the most intense sort of blues feeling, a mixture of disgust, disgrace, rage, and “every emotion” that might make a boy cry and scream, he’s terrorized into silence by whiteness-as-violence.

If we can grant that what King feels here is, in fact, the blues, then we might reasonably ask, What happens to this feeling? Where does it go? It finds late-life expression as autobiographical confession, to be sure, but how does it shape King’s musical production? In his earlier statement about living under “fear of the boss,” he speaks about how he broods afterward on such moments and becomes “really bluesy” because he is “hurt deep down,” and how he sings from that feeling as a way of “trying to say what the blues is to me.” The next most important source of blues feeling, he insists, “which is relatively minor compared to living like I have, is your woman.” Yet most of King’s hit recordings are about women, and none of them openly address white racial violence. Quite a few of them, in fact, exemplify the up-to-date power and promise that black consumers, according to Wald, are far more compelled by than any sounding of folkloric melancholy. How do we make sense of this paradox?

We are left, I think, with no choice but to take King at his word about the sources of his art. And we are forced to modify Wald’s claim in a way that allows blues music to speak from, and call to, currents of feeling—embodied individual sadness with collective resonance—that may not be immediately and universally discernable in the lyrics or stylistics of specific songs. In Seems Like Murder Here, I used the term “transcode,” drawn from philosopher Paul Gilroy, to speak about the way a blues musician’s meditations on racial violence might express themselves as narratives of romantic loss.29 For all we know, for the black audience that made King a star, the appeal of King’s music may have been his singular ability to fuse a forward-looking rhythm-and-blues aesthetic with a “cry” sourced in the feelings generated by his youthful wounding; his gift for transcoding individual and ancestral trauma into elegant and feelingful songs addressed to the “baby” who has done him wrong.

My “Teaching the Blues” handout offers a long catalog headlined “blues feelings.” Blues feelings, the emotions that lead people to sing the blues and that are frequently referenced in the lyrics themselves, are more diverse and nuanced than they might first appear. Many of them are grounded in varieties of loss or lack or both; the “good” blues feelings often speak to moments when loss and lack have been alleviated, at least temporarily. Keeping Gilroy in mind, it may be possible to hear the deeper meanings that linger behind the blues’ familiar invocations of loss and lack.

Loneliness, for example. Loneliness is one of the most primal feelings evoked in the blues. I’m a poor boy a long way from home. I ain’t got nobody. We tend to hear such invocations as cries of romantic or familial despair: there’s nobody around to hug and hold me, give me shelter, tell me I’m their special somebody. That’s an entirely valid reading—one that enables blues universalism without foreclosing black bluesism. Black male blues performers back in the day traveled widely, often solo; few of them enjoyed a settled domestic life complete with home, hearth, spouse, and children. But the loneliness evoked in such lines has another, more pointedly racial dimension, one connected with vulnerability in Jim Crowed public space. Vagrancy laws had such rambling men as their prime targets; lynch law was markedly more suspicious of what it called “strange Negroes”—black men not on the plantation payroll and unknown to local whites. Honeyboy speaks in his autobiography of how important it was to have a white man around who could speak in your defense.30 (He may not have wanted a boss, but he knew how helpful they could be.) In that sort of context, invocations of loneliness could speak to deeper kinds of vulnerability and unwantedness; they could transcode a yearning for protection from the storm, from that ever-present threat that could reach down out of the skies and carry you off.

Blues, as a dialectical art, often works on multiple levels simultaneously. A lover creates a world for you, distancing you psychologically from the harsh, unloving, potentially deadly world of southern segregation. The loss of a lover, in such a context, can be particularly devastating, because you are left alone with your fears, your isolation, and your exploitation. Lynch law has you in its sights if you head out onto the highway; the cotton fields are all you’ve got if you stay put. “Loneliness,” in such a context, is a freighted term; it has a romantic dimension, to be sure, but it carries more weight than that.

James “Son” Thomas and Walter Liniger

(courtesy of Walter Liniger)

I’ve been speaking here not just about loneliness but also about romantic abandonment. James “Son” Thomas, a Mississippi Delta bluesman and gravedigger whom folklorist William Ferris once referred to as his guru, evokes that primal scene as well as anybody I know. “I get a feeling out of the blues,” he told Ferris:

That may be because I been worried a lot. After my first wife quit me, I had the blues. I was working in the field, and I come in one evening. I had bought a pack of cigarettes. I never will forget that. A little boy told me, “Your wife gone.”

And I got sick all at once. I said, “I know she gone.”

“She carried away all her clothes.”

I said, “Get on away from here, boy.”

But that hurts you. After that, anytime you get lonesome, you gonner want to hear some blues.31

Romantic hopelessness is a third sort of blues feeling, one that enters the blues lyric tradition in several different ways. In Bessie Smith’s “I Ain’t Got Nobody” (1925), the singer’s romantic hopelessness is accompanied by loneliness; both feelings follow on the heels of abandonment by a “lovin’ man” who has “throwed [her] down.” “I sings good songs all the time,” Smith complains. “Won’t some man be a pal of mine? / I ain’t got nobody, nobody, ain’t nobody cares for me.” In Howlin’ Wolf’s “Killing Floor” (1964), by contrast, hopelessness isn’t generated by abandonment but by mistreatment—and, crucially, by the singer’s foolish willingness to endure that mistreatment. “I should have quit you … a long time ago,” he sings, bemoaning the fact that, not having left her, he now finds himself “down on the killing floor,” a reference to the location in a slaughterhouse where livestock is killed and butchered. Here again, death shadows love in a blues context.

Anger at romantic mistreatment or rejection: a familiar blues feeling. In psychiatrist Elisabeth Kubler-Ross’s schema, anger is the second stage of grief precipitated by loss or threatened loss.32 Honeyboy Edwards talks about the homicidal jealousy that he strove to steer clear of when he thought about messing around with beautiful women whose husbands or lovers might take it badly; this sort of rage, in a blues context, is as likely to lash out at the philandering beloved as at the meddling outsider: “If I can’t have you, nobody else will.”33 The all-points dispossession that marks black southern blues lives, ameliorated by the joys of sexual love, becomes intolerable the moment love turns fickle and is withdrawn, especially when a third party is involved. This is the theme of Ma Rainey’s canonical “See See Rider Blues” (1925):

See, see, rider, see what you done done, Lord, Lord, Lord

Made me love you, now your gal done come

You made me love you, now your gal done come

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

I’m gonna buy me a pistol, just as long as I am tall, Lord, Lord, Lord

Gonna kill my man and catch the Cannonball

If he don’t have me, he won’t have no gal at all.

Although this particular narrative of romantic mistreatment seems a straightforward story of jealousy and violence, black blues romance is always shadowed by the possibility of white malfeasance. When blues musicians wanted to curse out their bossman, they didn’t just curse at the mule; they sang about the woman or “baby” who had mistreated them. When Mississippi-born pianist Eddie Boyd (1919–94) spoke to interviewers Jim O’Neal and Amy van Singel in 1977, he claimed to have narrowly evaded lynching on three occasions before he was twenty-three, simply because he refused to be disrespected or whipped by his white employers. “They were always beating some black man to death down there,” he said. “I went through terrible experiences here in this country, man. Just because I didn’t buck dance and scratch behind my head when I’m looking at a white man.”34 He fled for his life after the third dispute, moving first to Memphis, then Chicago, before eventually resettling in Europe. In “Five Long Years” (1952), he uses romantic mistreatment to signify on workplace mistreatment:

Have you ever been mistreated? You know

just what I’m talking about.

Have you ever been mistreated? You know

just what I’m talking about.

I worked five long years for one woman,

she had the nerve to put me out.

I got a job in a steel mill, shucking steel like a slave.

Five long years, every Friday I come straight

back home with all my pay.

Have you ever been mistreated? You know

just what I’m talking about.

I worked five long years for one woman,

she had the nerve to put me out.

“Put me out,” in this context, signifies on the familiar mode of white reprisal against an insubordinate plantation hand: the bossman’s nonnegotiable demand that the troublemaker pack up his belongings and “be off the place by sundown.”

Homesickness is a blues feeling—the emotional obverse, in a sense, of the restlessness, rage at mistreatment, spirit of free enterprise, and urge to partake of the world’s pleasures that leads so many blues performers to ramble. The blues tradition here takes its cue from American popular music, which has been mining the theme of yearning for the “southern home” at least since Stephen Foster’s “Old Folks at Home” (1851). Even as they evoke a dozen different reasons for heading down the big road that speeds them away from mistreatment and north toward the promise of Chicago and New York, blues performers also pause to reflect on the changed circumstances into which migration has thrown them. In some cases they sing longingly of returning home, as in Roosevelt Sykes’s “Southern Blues” (1948): “Chicago and Detroit. Folks have you heard the news? / Old Dixieland is jumping, I’ve got those southern blues. …”

Anxiety, often with an admixture of fear, is a quintessential blues feeling. Its sources are many and varied. Anxiety is a reasonable response—a suppressed flight-response—to racial terrorism, especially the threat of lynching, but it’s also a reaction to the knowledge that one is being financially exploited for another’s gain. Much more widespread in the blues tradition are the anxieties that result from troubled romance: the forward-projected yearnings that occur when you’re opening yourself to a new lover and desperate for acknowledgement, and, on the other end, the pain that accompanies a bad fight or a breakup. Being anxious in this way isn’t the same as being heartbroken, although it may accompany heartbreak. When I was twenty-six, my live-in girlfriend of five years left me for somebody I knew. I experienced the sort of lonely desolation that James “Son” Thomas evokes with such stark force, but I also came face to face with the anxiety I’ve sketched here. It struck me with the force of a revelation, an augury of mental breakdown, although the latter never quite took place. Knowing more or less where she was—at his apartment, twenty blocks away—I found it physically impossible, many nights, to sit by myself in what was now my, rather than “our,” apartment. I was haunted by what was not there. It was during this period of my life that I began to frequent a blues club in the East Village, drinking and losing myself in the music, letting the grooves and songs, many of which suddenly took on profound meaning, comfort me as best they could. Albert Collins’s “My Mind Is Trying to Leave Me” (1983) dug particularly deep: “I began to think about my baby / Aha, like a crazy fool would do / You see, my woman gone away an’ left me / An’ now my mind is tryin’ to leave me too.” On one occasion, literally shaking, I called a good friend from the club and begged him to let me sleep on the floor of his apartment because the thought of sleeping in my own bed, formerly “our” bed, filled me with dread. It sounds surreal now, but it was quite real then—that preternatural anxiety and the way blues music helped voice it and keep it at bay. No other available music, and certainly not the synth-pop of the mid-1980s, spoke to my condition and purged my anxiety the way blues did.

The fact that I, a white man, can offer this particular response to the blues call might stand as counterevidence for the black bluesist declaration, “Blues is black music.” Although some white investments in the blues are surely invidious—profiteering, minstrelized, callow, touristic—others are deep and transformative. My baptism in the blues was the secular equivalent of a conversion experience, a spiritual rebirth; it led me into an apprenticeship with a Bronx-born black harmonica player, a five-year stint as a Harlem street musician, a lifelong partnership with the older black Mississippi-born guitarist I met there, an interracial marriage, an academic career devoted to blues literature and culture, and a decades-long blues harmonica teaching practice in which, among other things, half a dozen black men have sought me out for private lessons.35 To dismiss those sorts of investments and relationships as essentially trivial, as Black Rock Coalition founder Greg Tate does in Everything but the Burden: What White People Are Taking from Black Culture (2003), is to misrepresent the true scope of the music’s transformative powers, powers that are themselves a product of the music’s long confrontation with the evilest of circumstances.36 By the same token, it is vital that we attend to the specific ways blackness inflects blues subjectivity—marking the difference, for example, between my own anxious encounter with the blues occasioned by romantic loss and the encounter with “Mr. Blues” evoked by Little Brother Montgomery (and later covered by Buddy Guy) in “The First Time I Met You” (1936):

The first time I met the blues, mama,

they came walking through the wood

The first time I met the blues, baby,

they came walking through the wood

They stopped at my house first, mama,

and done me all the harm they could

Now the blues got at me, lord, and run me from tree to tree

Now the blues got at me, and run me from tree to tree

You should have heard me begging Mr. Blues, don’t murder me

Blues songs rarely signify on lynching, but this one does, with startling directness. Every element of the ritual is named except the rope: the terrifying but unspecified mob-wrought tortures adumbrated by “all the harm they could”; the “tree” where such rituals frequently took place. “Blues,” in this case, is the lynch mob itself, personified in the figure of Mr. Blues—“Mr.” being the honorific that every white man in the South demanded, on pain of beating or death, from every black man. The song is aligned with Montgomery’s own anxious, fearful temperament, to judge from the portrait offered by New Orleans banjoist Danny Barker:

Little Brother was a master at travelling through the south. I noticed that he never stopped at any place that was owned or operated by white folks. When he wanted to stop for food or drink he would ask some coloured person where there was a coloured place. He drove slowly and carefully when passing through a community. He watched the road like a hawk, but when we hit the outskirts he’d sigh and relax.37

The anxiety I felt in the aftermath of romantic loss, frightening as it was, was merely personal; the abject fear evoked in Montgomery’s song and corroborated by Barker’s recollections are personal soundings of a much broader social ill, the terror inflicted by whites and suffered by blacks under the reign of Jim Crow. Yet blues music speaks to and for both of us.

My “Teaching the Blues” sheet lists anxiety as part of a subset of blues feelings that includes fear, restlessness, terror, fury, and bitterness. Fury and bitterness, like the other emotions, manifest lyrically in both romantic and political contexts; they’re directed not just toward lovers and competitors but also toward those who inflict a range of injustices, including racial ones. Another subset of negative blues feelings, directed inward rather than outward, includes a sense of worthlessness, shame, or guilt. Commentators such as Albert Murray, evoking blues music as a kind of sonic force field that drives away bad feelings and evinces a spirit of prideful resistance, tend to understate the degree to which some blues songs hold up the white flag of spiritual surrender. “It’s my own fault, baby,” B. B. King sings in “My Own Fault, Darlin’” (1952), “treat me the way you wanna do.”

And then, because the blues are relentlessly dialectical, our catalog of blues feelings tacks suddenly in the direction of hope. A sense of renewed possibility, hopefulness, or potency: the sector of the blues lyric and performance tradition that speaks to the moment when, as in “Trouble in Mind,” the clouds dissipate, the promised “some day” arrives, and the sun finally shines in your back door. A lot of people are under the mistaken impression that the blues, perhaps because it’s been (rightly) associated with the burdens of black history, is uniformly a music of downheartedness and despair. But that’s no more than a half-truth. The blues musician’s role has always been to conjure good feelings out of bad, using lyrics, rhythm, and onstage stylistics—a sense of dramatic occasion and the right amount of swagger—as magic wands. Someone who has the blues may feel that the world has broken apart in the worst kind of way, or is merely a cross to be borne, but the right kind of song and groove, in the right hands, have the power to resuscitate. Blues music can drive away your despair and put the swing back in your step. The community is a crucial part of this process. When I was suffering the blues actively as a newly single young man and couldn’t abide my own apartment at night, I’d drive down to Dan Lynch, that East Village juke joint, where the Holmes Brothers, an African American trio of wise older men, were the house band presiding over the weekly jam sessions. I’d get a drink, or a few drinks, and sit at the bar listening to songs about the women who’d done them, and me, wrong; I’d lose myself in edgy guitar solos that tracked and voiced my pain, share in the yells of approval that the room gave back to the bandstand. I’d look around at the motley interracial brotherhood and decide that I’d found my place and that all was not lost. Later I’d stride out the swinging front doors, music vibrating through me, ready to call it a night. Feeling just fine, for the moment.

The Holmes Brothers

(© Joseph A. Rosen)