bar 9

Ralph Ellison, Richard Wright, and the Southern Blues Violences

BRUTAL EXPERIENCE AND LYRIC FLIGHT

If Handy, Hughes, and Hurston help usher the blues literary tradition into being, then one thing that unites them is a shared concern with two issues that have proven to be central to that tradition: the dialectical energy—pain and pleasure, tragedy and comedy—marshaled by the music and its congregants, and the representational strategies through which blues lyricism can be displaced onto the written page. Ralph Ellison, too, is a canonical blues literary figure, and his description of the blues in a 1945 review-essay, “Richard Wright’s Blues,” has been extraordinarily influential over the years, in part because it addresses both issues, embracing the blues’ bittersweet tonality and enlarging their scope to encompass prose literature. “The blues,” Ellison proposed,

is an impulse to keep the painful details and episodes of a brutal experience alive in one’s aching consciousness, to finger its jagged grain, and to transcend it, not by the consolation of philosophy but by squeezing from it a near-tragic, near-comic lyricism. As a form, the blues is an autobiographical chronicle of personal catastrophe expressed lyrically.1

In Bar 8, I invoked Memphis Minnie’s “Bumble Bee” and Bessie Smith’s “Empty Bed Blues” as plausible sources for the pleasure-and-pain dialectic evidenced by Their Eyes Were Watching God; Ellison opens that interpretive door in another famous passage from the same essay. “Like a blues sung by such an artist as Bessie Smith,” he wrote of Wright’s autobiography, “its lyrical prose evokes the paradoxical, almost surreal image of a black boy singing lustily as he probes his own grievous wound. … Black Boy represent[s] the flowering—cross-fertilized by pollen blown by the winds of strange cultures—of the humble blues lyric” (91).

Many decades later, we’re still exploring the implications of those words “flowering” and “cross-fertilized.” In what way, precisely, do the “humble blues lyric”—more specifically, tens of thousands of blues recordings—and the African American literary tradition speak to each other? Is the fusion of blues lyrics with more traditional Western literary forms, such as the autobiography, the only way, or the most important way, or merely one important way, in which blues literature flowers into being? Or does the blues impulse, as Ellison conceives of it, animate the tradition: a desire not merely to narrate (or sing) an experience characterized by the words “painful,” “brutal,” and “aching,” but to beat it back with an admixture of humor so that the blues ethos is embodied? And where, in all this, are the blues musicians themselves—performers who sing the songs, exemplify the impulse, and live out the ethos? Janie’s autobiographical chronicle in Their Eyes, after all, was shaped by the active intervention of Tea Cake, a guitar-picker and piano-tickler; he was the bumble bee who cross-fertilized her world with the blues and contributed directly to her flowering. When we’re seeking to assess the blues content of particular literary texts, how critical is the presence of such blues-musical figures?

One way of exploring such issues, I suggest, is to make Black Boy a test case. Does Wright’s autobiography truly deserve to be called a work of blues literature? Wright makes no attempt, after all, to depict the blues culture that was thriving in the Mississippi and Arkansas of his youth, a culture of street-corner busking and all-night-long house parties presided over by a loosely organized brotherhood of skilled, promiscuous, highly mobile songsters—a world rendered in rich autobiographical detail by Honeyboy Edwards in The World Don’t Owe Me Nothing. Young Richard does, at one point, stand outside a saloon in Memphis; somebody gives him a drink and teaches him some filthy language—language he repeats for the amusement of the bar’s patrons until, later, he is beaten badly for repeating it at home. This could be an urban juke joint, except that no music is audible, here or elsewhere in Black Boy. Nor does Wright offer us blues lyrics rendered on the page, as three-line stanzas or briefer lyric echoes, in the manner pioneered by Handy, Hughes, and Hurston. Wright doesn’t actually sing the blues per se; Ellison is being purely metaphorical when he characterizes young Richard as “singing lustily.” Where, then, is the presumed bluesiness of Black Boy sourced? Did Wright just somehow absorb the blues, thanks to his blackness and his Deep South upbringing?

In the summer of 1921, when Wright was fourteen, he made a brief, disillusioning tour of the Mississippi Delta as an assistant to W. Mance, an illiterate black insurance agent. “I saw a bare, bleak pool of black life and I hated it,” he wrote in Black Boy. “The people were alike, their homes were alike, and their farms were alike.”2 Where young Wright saw a bleak and uninspiring tableau of subsistence-level peasantry, devoid of the individuating expressiveness enabled by the blues, Edwards speaks of a Delta childhood animated and enriched by the music—but also marked by the violence that pervaded southern blues culture:

Mama … could play guitar and harp. She’d put a guitar across her lap with a pocket knife and play “Par-a-lee” on it. We was all kind of musical people. Didn’t none of her family but her play music, but on my father’s side was musicians. He played violin and guitar but he got rid of them after I got up to be a little size; he quit playing.

Papa used to hold country dances on a Saturday night, sell whiskey and play guitar at the house. Sometimes he’d go off to play at jukes. He got in a fight one time at one of them Saturday night dances. My daddy got to fighting and hollering with a guy and they run out of the dance and into the field. My daddy had a plaid shirt on and this guy Jack shot at him with a Winchester rifle. The bullet just missed Papa, but it shot a hole through his shirt! Then he quit playing.3

Although Wright was not, according to biographer Hazel Rowley, “tempted by saloons, shooting craps, or houses of ill repute” after moving to Memphis with his mother in 1925, he did occasionally visit the Palace Theatre on Beale Street during his two-and-a-half-year residence and listen to Gertrude Saunders, a touring vaudevillian, sing the blues.4 That’s not much cultural exposure, at least when compared with the much deeper well from which Hughes and Hurston were drawing. Ellison later backpedaled, as it happens, on his early claims about Wright’s literary bluesiness. “For all of his having come from Mississippi,” Ellison told interviewer Robert O’Mealley in 1976, “he didn’t know a lot of the folklore. And although he tried to write a blues, he knew nothing about that or jazz.”5

The written blues Ellison disparages here is almost surely “King Joe (Joe Louis Blues),” a thirteen-stanza blues song that Wright composed in 1941 at the suggestion of producer John Hammond in honor of boxer Joe Louis’s recent triumphs. A shortened version of “King Joe” was set to music by Count Basie and performed on record by actor Paul Robeson in his deep, powerful, operatic basso. “The man certainly can’t sing the blues,” Basie later mused of Robeson, but Wright’s labored lyrics were no help to the swing-challenged singer—although the producers were shrewd enough to leave a half-dozen of the clunkiest stanzas off the recording, including the following:

Big black bearcat couldn’t turn nothing loose he caught (2x)

Squeezed it ’til the count of nine, and just couldn’t be bought

Now molasses is black and they say buttermilk is white (2x)

If you eat a bellyful of both, it’s like a Joe Louis fight

Wonder what Joe Louis thinks when he’s fighting a white man

Say wonder what Joe Louis thinks when he’s fighting a white man

Bet he thinks what I’m thinking … ’cause he wears a deadpan6

Although Wright would, in later years, occasionally revisit the blues in poems such as “Blue Snow Blues” and “The FB Eye Blues,” liner notes for albums by Josh White and Big Bill Broonzy, and an influential foreword to Paul Oliver’s Blues Fell This Morning: The Meaning of the Blues (1960), his commitment to blues vernacular culture pales beside that of Hughes, Hurston, Brown, Sherley Anne Williams, August Wilson, Albert Murray, and Ellison himself.7 Yet a crucial distinction needs to be made here between blues expressiveness and blues feeling. Wright may not, as Ellison claimed, have known how to write a convincing blues song, and there is no record of him singing the blues. But it might be argued—and I am about to argue—that he had the blues as a Mississippi black boy, lived a life structured by blues feelings that he shared with his peers and elders—including the sorts of blues performers whom he chose later, as a writer, not to represent. The source of these feelings, as Ellison suggests, is a brutal experience composed of painful details and episodes that the blues subject, a subject half-created by this experience, chooses to keep alive in aching consciousness.

As a way of making that argument and teasing out the implications of Ellison’s statement, I’ll begin with a claim that I’ve already evidenced: blues expressiveness is grounded in and shaped by the encounter of working-class black folk with violence in the Jim Crow South. There’s more to blues expressiveness than that, of course, as other critics have argued. The aesthetic and attitudinal contours of the music are also shaped by the spatial mobility made possible by a post-Reconstruction southern railway system and the sonic textures engendered by that system’s horizon-bound trains; by the consolidation of a mass audience with the emergence of a race records market and its technologies of reproduction; and by the way the new sexual freedom of post-Emancipation life was explored by the music’s black producers and consumers.8 Yet southern violence is, I would argue, a more thoroughgoing influence on blues lives, blues feelings, and blues song than these other three domains, in part because it hovers behind them—prompting dreams of escape and fears of pursuit, for example, and infecting intimate relationships. This violence consists of three distinct but interlocking forms of interpersonal violence: disciplinary violence, retributive violence, and intimate violence.

Disciplinary violence, to reiterate, is white-on-black violence that aims, in white southern parlance, to keep “the Negro in his place”; it consists primarily of lynching, police brutality, and related forms of white vigilantism. When Ellison speaks in “Richard Wright’s Blues” about young Richard having come of age in a world ruled by “an elaborate scheme of taboos supported by ruthless physical violence” (95), he is offering a succinct definition of disciplinary violence as it functioned in Mississippi between 1890 and 1965. Little Brother Montgomery’s 1936 recording, “The First Time I Met You,” with the singer’s cry of having been “run from tree to tree” by the blues and his plea, “Mr. Blues, don’t murder me,” exemplifies the blues response to disciplinary violence.9 Robert Johnson’s preternaturally restless “Hell Hound on My Trail” (“I got to keep movin’ / I’ve got to keep movin’ / blues fallin’ down like hail”) is similarly haunted by the presence of white violence in the landscape it evokes, in the mobility it both enacts and laments.

Retributive violence, somewhat less common in both southern history and blues song, is black-on-white violence that strikes back, or threatens to strike back, at disciplinary violence and other forms of racist oppression, sometimes with a kind of badman swagger. “Stackolee,” which features a St. Louis lawman who is leery of confronting that “bad son-of-a-gun they call Stackolee,” is a badman blues ballad that flirts with retributive violence.10 Luzanna Cholly, the nattily attired Alabama bluesman in Albert Murray’s novel Train Whistle Guitar (1974), is a hero to the young black narrator precisely because, with inimitable cool, he threatens retributive violence. “The idea of going to jail didn’t scare him at all,” Murray tells us,

and the idea of getting lynch-mobbed didn’t faze him either. All I can remember him ever saying about that was: If they shoot at me they sure better not miss me they sure better get me that first time. Whitefolks used to say he was a crazy nigger, but what they really meant or should have meant was that he was confusing to them. … They certainly respected the fact that he wasn’t going to take any foolishness off of them.11

Intimate violence, the third kind of blues violence, is black-on-black violence driven by jealousy, hatred, and other strong passions, particularly the cutting and shooting that cut a wide swath through blues song and blues literature. Ma Rainey’s “See See Rider Blues,” which climaxes with a verse in which the singer swears she’s going to kill her abandoning lover with “a pistol just as long as I am tall,” exemplifies this sort of intraracial vengeance. Intimate violence is a particularly fruitful axis around which to align blues lyrics and blues literature; knives, for example, surface not just in songs such as “Got Cut All to Pieces,” “Good Chib Blues,” and “Two-By-Four Blues,” but novels such as Walter Mosley’s RL’s Dream, Murray’s Train Whistle Guitar, Gayl Jones’s Eva’s Man, and Hurston’s Their Eyes Were Watching God, poems such as Hughes’s “In a Troubled Key” and “Suicide,” plays such as August Wilson’s Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom and Seven Guitars, and autobiographies by David Honeyboy Edwards, Henry Townsend, and others.

FINGERING THE JAGGED GRAIN

Richard Wright may not have known how to write a blues, as Ellison later insisted, but he did know how to evoke these three Jim Crow violences, which together constitute much of the brutal experience he suffered and survived, and which likewise reveal his underlying affinity with the blues textual tradition I’ve just sketched. In this respect, Ellison’s characterization of Black Boy as a kind of literary flowering of the humble blues lyric is apt. Not only were Wright (b. 1908) and Little Brother Montgomery (b. 1910) contemporaries who came of age in the Delta, for example, but Montgomery’s signifying protest against lynching in “The First Time I Met You” is uncannily echoed in Black Boy’s evocation of the terror produced in his youthful imagination by the phantasmic lynch mob. “I had already grown to feel that there existed men against whom I was powerless,” Wright insisted of his Deep South boyhood, “men who could violate my life at will. … I had already become as conditioned to their existence as though I had been the victim of a thousand lynchings” (87). Here is one audible blues-note in Wright, a note born out of the black southern subject’s confrontation with the threat of disciplinary violence. Another blues-note can be heard when Wright reports a story he’s been told about one woman’s response to such violence. “One evening,” Wright tells us,

I heard a tale that rendered me sleepless for nights. It was of a Negro woman whose husband had been seized and killed by a mob. It was claimed that the woman vowed she would avenge her husband’s death and she took a shotgun, wrapped it in a sheet, and went humbly to the whites, pleading that she be allowed to take her husband’s body for burial. It seemed that she was granted permission to come to the side of her dead husband while the whites, silent and armed, looked on. The woman, so went the story, knelt and prayed, then proceeded to unwrap the sheet; and, before the white men realized what was happening, she had taken the gun from the sheet and had slain four of them, shooting at them from her knees. (86)

Wright’s tale resonates with blues singer Josie Miles’s 1924 recording, “Mad Mama’s Blues,” which threatens shotgun-wreaked vengeance against a blues-inducing world:

Wanna set the world on fire, that is my one mad desire

I’m a devil in disguise, got murder in my eyes

Now I could see blood runnin’ through the streets

Now I could see blood runnin’ through the streets

Could be everybody layin’ dead right at my feet

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

I took my big Winchester, down off the shelf

I took my big Winchester, down off the shelf

When I get through shootin’, there won’t be nobody left.

In his review of Black Boy, Ellison evokes this sort of blues-bearing retributive violence when he speaks of “three general ways” in which black folk confronted their destiny “in the South of Wright’s childhood,” the third way being to “adopt a criminal attitude, and carry on an unceasing psychological scrimmage with the whites, which often flared forth into physical violence” (94).

What interests Ellison far more than black badman (or badwoman) vengeance against whites, however, is the linkage he glimpses in Wright’s Mississippi boyhood between white disciplinary violence, especially lynching, and black intimate violence, an intimate violence that took the form not of mayhem in the jooks but of beatings Wright suffered at the hands of his mother and grandmother. “Wright saw his destiny,” Ellison writes, “… in terms of a quick and casual violence inflicted upon him by both family and community” (94). This family violence, the violence of black southern elders against their children, is viewed by Ellison as a problematic but understandable attempt to suppress a rebellious individuality that, were it expressed by these children, would be met with white reprisal against the entire black community. Later he elaborates: “One of the Southern Negro family’s methods of protecting the child is the severe beating—a homeopathic dose of the violence generated by black and white relationships. … Even parental love is given a qualitative balance akin to ‘sadism’” (101). Many would dispute Ellison’s depiction of black family life under Jim Crow—a sympathetic paraphrase, clearly, of Wright’s unremittingly bleak rendering. Yet Wright’s vision of intimate violence as the passion-driven inflicting of beatings on the people one is closest to is a blues vision of sorts, one that links his autobiography with blues song and the blues literary tradition.

In blues song, this sort of intimate violence issues more frequently against a lover than a child—as when Robert Johnson in “Me and the Devil Blues” (1938) sings, “I’m goin’ to beat my woman / until I get satisfied,” or Muddy Waters in “Oh Yeah” (1954) cries, “Oh yeaaah, someday I’m goin’ to catch you soon / cut you in the morning, whup you in the afternoon.” The beatings that slowly infect the relationship between Janie and Tea Cake in Their Eyes offer similar testimony. It might be argued that what I am calling intimate violence in Wright’s case—black southern elders whipping a child to keep him in line—is actually a kind of second-order disciplinary violence, the internalization, transformation, and anticipatory staging of a far more deadly and indiscriminate white disciplinary violence that those elders hope to ward off. This is precisely Ellison’s claim, in fact. In Black Boy, however, boundaries between the two sorts of violence begin to break down; the black disciplining gesture is resisted and thereby forced into the open, revealed to be a form of naked aggression not much different from a knife-slashing. The starkest example of this is the moment where young Richard watches his Uncle Tom tear “a long, young, green switch from the elm tree” (186) and determines not to be beaten by the older man. Richard goes to his dresser drawer, gets out a pack of razor blades, and arms himself with “a thin blade of blue steel in each hand” (186–87). This gesture aligns him with the blues lyric and literary tradition—with Waters (in “Walking thru the Park” [1959]) singing, “Don’t you bother my baby, no telling what she’ll do / She might cut you, she might shoot you too,” and with Tea Cake arming himself with blades and cards before leaving Janie and heading off to a local juke. “I’ve got a razor in each hand!” young Richard warns his uncle in “a low, charged voice.” “If you touch me, I’ll cut you! Maybe I’ll get cut too, but I’ll cut you, so help me God!” (187). If intimate violence is a way southern blues people and their migrant peers express some of their fiercest feelings, then young Richard’s gesture of revolt transforms the scene of parent-child discipline into a kind of juke joint brawl—albeit a brawl lacking both the rich musical context and elaborate social context (frontier brags, half-mocking threats at the gambling table, sexual possessiveness) that Hurston encountered in the Pine Mill jook.

Richard Wright’s rebellion against his uncle’s threatened beating closely parallels an encounter described by St. Louis bluesman Henry Townsend in his autobiography, A Blues Life. Townsend, born in Shelby, Mississippi, the year after Wright was born in Natchez, is catapulted into his future career the day he learns, as a nine-year-old, that his father is going to beat him for blowing snuff in his cousin’s eyes. “My daddy was gonna get me for that,” he claims,

and that’s when I first left home. You don’t know how bad it hurts my feelings for me to think that somebody is gonna physically interfere with me, like hitting on me. You don’t know how bad it hurts me. My heart jumps and tears in two like busting a string. I can’t stand that. I don’t dish it out and I can’t stand it. I’ve been whipped but it wasn’t a pleasant thing for the man that whipped me—or me—I’ll tell you that.

… I didn’t give [my daddy] no chance [to whip me]. I caught the train. I didn’t know where I was going—I didn’t care. I knew I wasn’t gonna stay there and get a whooping.12

Wright is the Mississippi black boy who silently suffers the blues of disciplinary and intimate violence, finally rebelling when pressed to the breaking point but escaping only later to exorcise his blues up north in the form of a literary autobiographical chronicle. He has, in Trudier Harris’s memorable phrase, “no outlet for the blues,” or at least no musical outlet for those feelings.13 Townsend, by contrast, is the Mississippi black boy who refuses to stay put and allow those particular blues to be inflicted on him; his escape to East St. Louis is a creative liberation, the first step into eventual self-ownership marked by a mastery of blues song’s expressive vocabulary. Townsend is a blues lyricist as well as performer; when I spoke with him backstage at B. B. King’s Blues Club in New York in the summer of 2001, he mentioned pridefully that he was the composer of the blues standard, “Every Day I Have the Blues”—the original 1935 version by pianist Pinetop Sparks, on which he played guitar. Although he can’t take credit for the well-known lines added to the song by Memphis Slim in his influential 1949 version—“Nobody loves me, nobody seems to care / Worries and troubles, you know I’ve had my share”—it’s tempting to see the song as the declaration of a bitterly rebellious but euphoric nine-year-old runaway riding the rails north, away from his father’s blows. It’s also tempting to see those lines as the crystallization of young Richard Wright’s predicament: “Every Day I Have the Blues” is the humble blues lyric from which Black Boy seems to have sprung, even if Wright himself was incapable of singing that song in so many words.

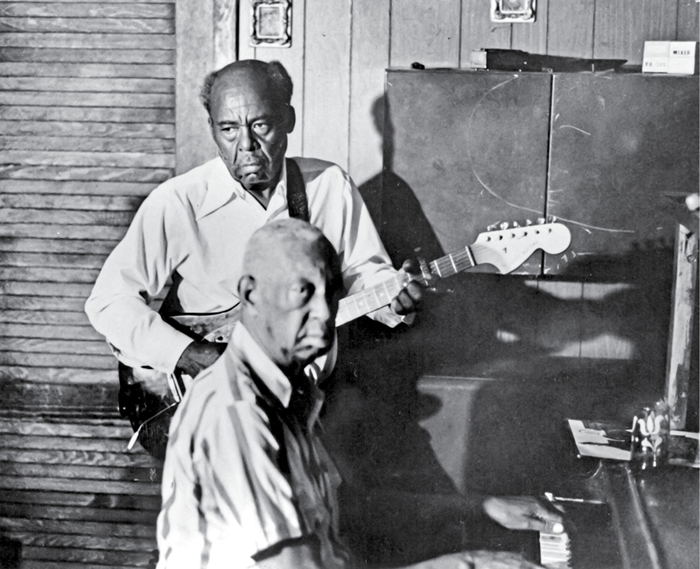

Henry Townsend (guitar) and Henry Brown (piano)

(courtesy of the photographer, Hans Andreásson)

Southern violence, considered in its entirety, doesn’t just hurt feelings. It produces a range of abject black bodies: beaten, battered, dismembered, dead. The bodies produced by white violence show up at several points in Black Boy—most notably, as the corpses of Uncle Hoskins and an acquaintance of Wright’s named Bob, both of whose lynchings-by-shooting are related to Wright by others—but these bodies are represented in a sketchy, fleeting way. The traumatic effect they have on young Wright is out of proportion with the unspectacular representations themselves, as though his own imagination were doing most of the terrorizing. In one of the few moments in Black Boy where retributive violence is imaged, the tale about the black woman who wraps a shotgun in a sheet to avenge the death of her mobbed husband, Wright is similarly circumspect; this story compels his attention by the sheer audacity of the woman’s act rather than the morbid details of the revenge-murders themselves. The most graphic spectacles imaged by Wright in Black Boy, it turns out, are the beatings he suffers at the hands of his mother and grandmother. The novel opens with such a scene after he has accidentally set the family’s house on fire:

“You almost scared us to death,” my mother muttered as she stripped the leaves from a tree limb to prepare it for my back.

I was lashed so hard and long that I lost consciousness. I was beaten out of my senses and later found myself in bed, screaming, determined to run away, tussling with my mother and father who were trying to keep me still. I was lost in a fog of fear. A doctor was called—I was afterwards told—and he ordered that I be kept abed, that I be kept quiet, that my very life depended on it. My body seemed on fire and I could not sleep. Packs of ice were put on my forehead to keep down the fever. (7)

If intimate violence produces shocking images of Wright’s battered body in Black Boy, where disciplinary and retributive violence only sketchily represent the bodily violations wrought on, and by, others, then all three violences intermingle in Wright’s imagination to evoke a portrait of southern black blues life as a desperate and humorless struggle, a living nightmare.

When we pay attention to the way this linked set of southern violences circulates within blues song and blues literature, it becomes clear that Black Boy stands simultaneously at the margins and the center of the blues textual tradition. The fact that it erases all traces of Mississippi’s thriving blues culture from the world it describes, with the ideological intent of depicting the unrelieved bleakness of black southern life, makes it marginal. Where are the belted-out blues songs described by James Cone as “an expression of fortitude in the face of a broken existence”?14 Where is the temporary but vital liberation claimed by black Mississippians—including Honeyboy Edwards’s father—at house parties and juke joints every Saturday night? Yet to the extent that Wright’s own life is an expression of fortitude in the face of a broken existence, one shaped by disciplinary, retributive, and intimate violence, Black Boy is indeed an exemplary blues text, one animated by the deepest of southern blues feelings.

ELLISON’S VIOLENT BLUES HUMORS

In his own writings, Ralph Ellison represents the blues violences somewhat differently from Wright. Most important, perhaps, Ellison steers clear of the horror provoked by white racial terrorism, refusing to hold those experiences in aching consciousness as Wright does; he redeems desperation with humor rather than seconding it with unrelieved grimness. One explanation for this difference in approach is the social milieu in which each author grew up: relations between blacks and whites were considerably more benign in Oklahoma City during Ellison’s boyhood than in Mississippi and Arkansas during Wright’s, granting Ellison a more detached perspective.15 Ellison knows that lynching is a source of agony for black folk, as his short story “A Party Down at the Square” makes clear. But his decision to make the narrator of that story a white boy who admires the lynchers, rather than a black witness who shudders at them, reveals an inclination to reject helpless subjection in favor of very dark satire.16 The same impulse to heighten the comedic side of the blues’ tragicomic dialectic is at work in Invisible Man, where Ellison has Dr. Bledsoe, a Booker T. Washington stand-in who rules his Tuskegee-like empire with a ruthless hand, echo a pronouncement made by Mississippi’s most infamous white demagogue, James Vardaman. “I’ll have every Negro in the country hanging on tree limbs by morning,” thunders Bledsoe, “if it means staying where I am.”17 One can hardly imagine Richard Wright making this sort of joke. In his essay “An Extravagance of Laughter,” Ellison evokes a related form of disciplinary violence, aggressive southern policing, in a way that rejects Wright’s bitter pronouncements about “days lived under the threat of violence” for a more benign stoicism. “I gave Jeeter Lester types a wide berth,” Ellison acknowledges of his college days in Alabama, “but found it impossible to avoid them entirely—because many were law-enforcement officers who served on the highway patrols with a violent zeal like that which Negro slave narratives ascribed to the ‘paterollers’ who had guarded the roads during slavery. … (Southern buses were haunted, and so, in a sense, were Southern roads and highways). … Even the roads that led away from the South were also haunted; a circumstance which I should have learned, but did not, from numerous lyrics that were sung to the blues.”18

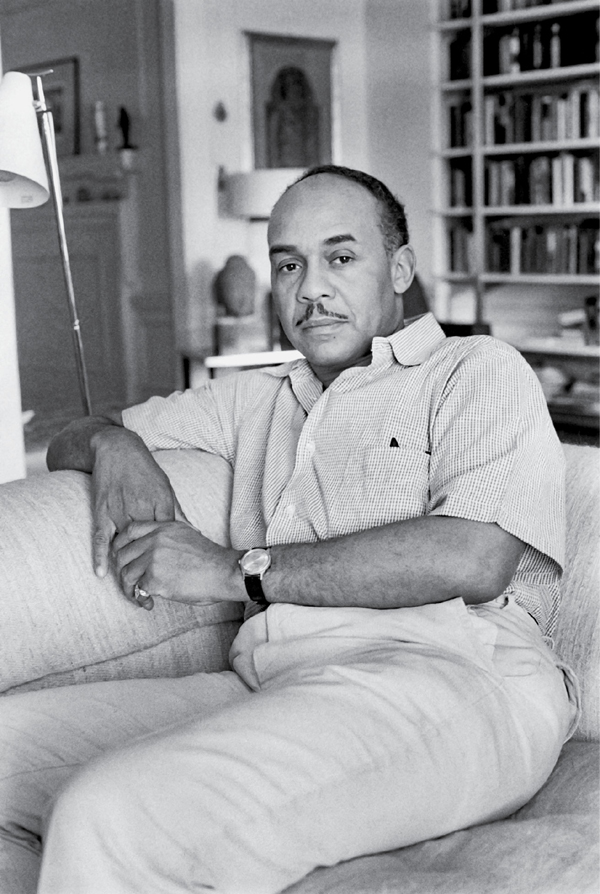

Ralph Ellison

(courtesy of Rockefeller Archive Center, Sleepy Hollow, N.Y.)

Ellison knows that white death haunts the southern roads traveled by black folk, but he refuses to be rendered psychologically brittle by this fact. The prospect, enactment, or aftermath of a lynching doesn’t function in Ellison’s work as the sort of destabilizing phantasm it becomes in Wright’s story “Big Boy Leaves Home” and his poem “Between the World and Me.” It functions instead as an existential challenge to be mastered and moved beyond. The metaphorical outlines of spectacle lynching, for example, surface in the celebrated Battle Royal scene of Invisible Man, where the narrator, wrestling blindfolded with a group of black boys while white onlookers take bets, is kicked by one white man onto an electrified carpet. “It was,” he tells us, “as though I had rolled through a bed of hot coals. It seemed a whole century would pass before I would roll free, a century in which I was seared through the deepest levels of my body to the fearful breath within me and the breath seared and heated to the point of explosion.”19 When lynching victims were burned, as the black victim in “A Party Down at the Square” is burned, the ritual was often referred to by whites as a “Negro barbecue.” Ellison is signifying on that ritual here: not, as Wright does, to image black abjection as a form of protest, but to dramatize the capacity of the black blues subject to resist tragedy with the help of improvisational dexterity—figuring out how to roll off the carpet without being hurt too badly. What Ellison’s Invisible Man is always seeking, often without knowing it, is the half-comic insight that wrings transcendence out of misery and frustration.

Retributive violence bursts forth on the second page of Invisible Man, and the instrument of retribution is a blues knife, a knife deployed against oppressive whiteness with a raging sense of grievance. “Oh yes, I kicked him!” exclaims the narrator, speaking of a “tall blond man” who has called him “an insulting name” and repeatedly cursed him after the two men have accidentally bumped into each other one night on the street and begun to struggle:

And in my outrage I got out my knife and prepared to slit his throat, right there beneath the lamplight in the deserted street, holding him in the collar with one hand, and opening the knife with my teeth—when it occurred to me that the man had not seen me, actually; that he, as far as he knew, was in the midst of a walking nightmare! And I stopped the blade, slicing the air as I pushed him away, letting him fall back to the street. I stared at him hard as the lights of a car stabbed through the darkness. He lay there, moaning on the asphalt; a man almost killed by a phantom. It unnerved me. I was both disgusted and ashamed. I was like a drunken man myself, wavering about on weakened legs. Then I was amused: Something in this man’s thick head had sprung out and beaten him within an inch of his life. I began to laugh at this crazy discovery. Would he have awakened at the point of death? Would Death himself have freed him for wakeful living? But I didn’t linger. I ran away into the dark, laughing so hard I feared I might rupture myself.20

Knives that show up in blues literature almost always do damage, from the razor with which a “little woman” in a Mississippi juke joint slits her abusive husband’s throat in Edwards’s autobiography, to the knife that Levee plunges into Toledo’s back at the end of Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom, to the knife that leads Bea Ella Thornhill to get rechristened “Red Ella” after she eviscerates her faithless lover Beau Beau Weaver in Train Whistle Guitar. These blues-blades are instruments of a fierce passion that rarely subsides without bloodshed. The Invisible Man’s knife is an exception. The hysterical laughter that wells up in Ellison’s protagonist at the absurdity of his situation and causes him to run away without using his knife—a violence-dissolving hilarity—is a calculated divergence from the harsh truth of blues culture. Ellison has taken what might be called the “hardening” laughter of the blues tradition and deployed it in a way that defuses his protagonist’s explosive feelings. This is a creative but fertile misreading of the tragicomic thrust of the blues.

Blues people may have told violent stories and sung violent songs that were annealed with humor, but that humor was a way of dealing with the fact that blues culture was, or could be, fearsomely violent, rippling with interpersonal grievances that mere laughter could not defuse. “They tell me she shot one old man’s arms off, down in Mississippi,” bluesman Johnny Shines recalled of blues singer Memphis Minnie, chuckling at the memory. “Shot his arm off, or cut it off with a hatchet, something. Some say shot, some say cut. Minnie was a hellraiser, I know that!”21 This sort of blues laughter is a way of maintaining psychological equilibrium in the face of a Jim Crowed social environment rendered deadly by the double-barreled threat of white disciplinary and black intimate violence. Ellison transforms this blues laughter, in his book’s opening scene, into something quite different: a psychological tool for defusing one’s own violence. There is little evidence to suggest that this is the way blues people in the Deep South actually dealt with the rage, terror, and sadness that white disciplinary violence provoked in them. They may have sometimes grinned in the white man’s face, as Levee’s father grins in the face of the white men who have raped his wife, but these grins dissolved neither their aggrieved feelings nor their fantasies of violent retribution. For the most part, blues people expressed their fury either by murdering the white men who had wronged them, as Levee’s father does, or, more typically, by redirecting those feelings at an acceptable target—which is to say, by using guns and knives against each other in juke joints and Chicago recording studios.

Ellison’s divergence from the harsh realities of blues violence in his novel’s opening scene can help us see more clearly what he’s trying to do in the novel’s portrait of Jim Trueblood, a blues-singing sharecropper who accidentally rapes his own daughter while dreaming restlessly in the family bed one night. Ellison elides from that portrait the feelings of bitterness that Trueblood might be expected to harbor after his wife Kate has furiously attacked and wounded him, and he transforms the disciplinary violence that haunted the South in the form of “Jeeter Lester types” into an instrument of comic vengeance. The sharecropper tells the narrator and Mr. Norton how “biggity school folks up on the hill” (52)—higher-class black folk—have tried to shut him up so that he won’t embarrass them in white eyes with his tale of low-down degradation. “They sent a fellow out here, a big fellow too, and he said if I didn’t leave they was going to turn the white folks loose on me. It made me mad and it made me scared” (52). But Trueblood’s fear of white reprisal fades in the face of profitable white fascination with his tale of dream-provoked incest. The rest of Trueblood’s portrait is free from the sort of looming redneck threat that marks “A Party Down at the Square” and “Flying Home.” Ellison’s satiric purpose leads him to make the white folks Trueblood’s “friends” and the “biggity [black] school folks” Trueblood’s ineffectual antagonists, stewards of a white lynch mob that never forms.

Ellison similarly soft-pedals the harsh realities of black southern blues culture when he depicts Trueblood as a man willing to sit still and allow his own wife to beat him down. Blues musicians do not generally let blows directed at them go unanswered; the life stories of Skip James, Henry Townsend, and Leadbelly offer us hardened survivors who don’t hesitate to strike back at anyone who manhandles them. But sometimes, as Honeyboy Edwards acknowledges, one’s wife is delivering justified payback for one’s transgressions. “Most of the time when we did fight,” Honeyboy admitted, speaking to this point, “I would be the cause of it. Because I would come in drunk, jump on her sometimes. Which I had no business doing. She’d cut on me! I’d be wanting to fight and she’d cut me up! She’d be right on me with that pocketknife. I got cuts all over me. Bessie was tough; she was bad with a razor blade.”22

Trueblood’s Kate, although not Bessie’s sort of natural-born brawler, levels a comically exaggerated attack on her sinful husband. Her determination to use every available object as a weapon—including, in sequence, “little things and big things,” “somethin’ cold and strong-stinkin’,” something that sounds “like a cannonball,” a double-barrel shotgun, some unnamed thing that digs into Trueblood’s side “like a sharp spade,” an iron, and finally an ax (61–63)—places her squarely in the blues tradition of intimate violence as expressive violence, violence that vividly communicates feelings. Ellison, in turn, forces us to look at the wounds suffered by Trueblood, including the “scar on his right cheek” (50) and the “wound” (53) around which “flies and fine white gnats” (53) swarm, in a way that connects him with August Wilson’s Levee, who lifts his shirt to show his bandmates his scarred chest. Flesh wounds, in both cases, bespeak deeper emotional wounds. What Ellison doesn’t offer us with Trueblood, however, is Levee’s sort of violent response. Trueblood suffers his wife’s blows, passively resigned. Yet he also transmutes his fate into self-acceptance with the help of the blues. One night, rejected by his family and his preacher, he gazes up at the stars and starts singing. “I sing me some blues that night ain’t never been sung before,” he remembers later, “and while I’m singin’ them blues I make up my mind that I ain’t nobody but myself and ain’t nothing I can do but let whatever is gonna happen, happen.” Months after the episode, living an uneasy truce with Kate and his daughter, he is also profiting richly from white folks who come by his shack to gaze at his wounds, listen to his story, and give him money. (They, Ellison wants us to understand, are the “flies and fine white gnats,” ethically diminished by their voyeuristic fascination with black misery.) Trueblood hasn’t just survived but prospered.

The blues are grounded in paradox—above all, the paradox that was African American life in the segregated South during slavery’s long aftermath. How can one be both free and imprisoned? And how can one get by in such a world? That was the situation confronted by blues people: free in name, significantly freer than they had been as slaves, but also hemmed in by white violence, part of the brutal experience Ellison invokes in his celebrated definition. Hemmed in by family, too, as Wright and Ellison tell it. The mother and grandmother that protect you also beat you; the daughter you love is also the daughter you have somehow ended up raping in your sleep. How can the blues do justice to these painful paradoxes? It can chronicle personal catastrophe, squeeze from that tale a near-tragic, near-comic lyricism, and hope for the best, as Jim Trueblood does—beaten down, regretful, but determined to persist, whistling a bittersweet melody as he rises to confront the uncertain life that awaits him.