‘Blighty, oh Blighty in about a Week’

Leave

Officers did much better than men in getting leave. They could expect it two or three times a year, while a single short trip home was the best the average Tommy could hope for. There was always a sense of unreality about going on leave. ‘All he seemed to want was to be at home and rest … we did all we could to strengthen him up but the time was all too short … he felt parting keenly.’ Robert Saunders's account described how he welcomed a son home from the Front in December 1915.1 Letters home are often filled with men's excitement about and anticipation of leave. Some did talk when they got home. Members of the Liverpool Territorials, we are told, spoke much about their experience to families and friends at social and sporting clubs.2 But how could they cross that chasm between life at the Front and in their homes, when so much about the war in France was simply unimaginable for their families? Overall, therefore, the actual experience of Blighty, the shock of suddenly being at home for a short time, is little documented in letters written during the war.

For officers who were single, leave meant family cosseting and catching up with the lives of brothers and sisters. Julian Grenfell was more privileged than most. Reaching the Front in October 1914, he twice enjoyed short trips back to his home at Taplow on the Chiltern Edge that winter. He was as predictably ecstatic about these leaves as he was about fighting. ‘I've never loved three days better,’ he told his mother in December, ‘it was absolutely perfect and better from being so unexpected.’ ‘I did love my last leave,’ he reiterated in February 1915. Then, projecting his own war fever onto his men, he declared, ‘you should have seen our men setting out from here for the trenches – absolutely radiant with excitement and joy to be getting back to fight again’.3

Ernest Smith, with no premonition of how short his life was to be, announced his plans with suppressed excitement in June 1915. He would arrive at Victoria on the 25th and be leaving on the 29th. ‘My idea is to have a quiet Sunday with you all at home,’ he told his mother, ‘and then bustle about on Monday and fix up about my kit.’ ‘I cannot run about visiting,’ he advised her, so he left it to her whom to ask on each spare day. He remained fussed about his kit, expressing his fears to his father that there would be ‘no end of things to think of’. A friend had warned him how little spare time he had found there was ‘but I expect he was rather more conscientious and minute than I shall be’. His leave turned out to be quite glorious, giving him renewed energy: ‘it seemed to go in a flash, but at the same time I feel as if I am going to enter with zest into everything here’.

When his next leave came round Ernest had won his spurs in battle but was more worn down as a result. There was an even chance of the next week he announced on 2 October 1915: ‘how I am looking forward to it!!’ He ended a breathless note next day ‘no more now as I can think of nothing but leave at the moment’. This time he worried that his men would lack his leadership while he was away. However, his right-hand man Sergeant Mould, he wrote later in a reassuring note, having arrived back after a comfortable journey, ‘I find has not lost the platoon in my absence, or misbehaved himself in any way!’4

When Graham Greenwell published his letters home he set them out in chapters, divided by the five spells of leave he was granted over two years from November 1915 to October 1917. They bookmarked his time at the Front. Graham was pleased that his first leave gave him the chance to introduce his friend Conny, whose leave coincided with his, to the family in London. ‘I shall clean up at the Grosvenor,’ he promised, writing from Courcelles. Back in the ‘rain and the gloom’ ten days later, he reflected that already in early November ‘the holiday seems like a distant and happy dream’. But the generosity of the officer leave rota at this period in the Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire Light Infantry undoubtedly did much to keep men like Graham optimistic. There was no news, but ‘the thought of seeing you all again next month keeps me cheerful and well’, he wrote in mid-December 1915.

Graham's second leave, in February 1916, was marked by a bad return crossing: ‘departures from the cabin though hasty were never too late … the sides of the boat were literally a mass of men groaning and swearing’. He was lucky to snatch a third ten-day leave in the run-up to the Somme, marred this time by a terrible sixteen-hour train journey back from Le Havre. It felt like a ‘long martyrdom’ when Graham's next leave was delayed until May 1917. But he was given three weeks then and another month that October, after Passchendaele. Many officers found this irregularity of leave as the war went on difficult to cope with. Tommies had no choice but to live with it.5

The officer rota for the East Surreys began three months after they landed at the end of October 1915. Billie Nevill started getting excited that his turn was coming in mid-November. In a letter to Mother, Elsie and Doff, to be sent on to Amy, Howard and Tom, he was at his most ebullient. ‘I don't want to see any fodder out of a tin the whole time I'm home, twiggez-vous?’ No peppermints or chocolates either, since he supposed he would be returning to them as staple fare all winter. ‘Toast I should like and coffee, buckets of it … a nice fried lemon sole, some haddock! A chicken!, some fresh green vegetables ( Stop it my tummy aches). And so on, ad lib.’ A warning, he felt, was in order: ‘I expect you'll find me a wee bit quick worded, but don't mind that.’ As men contemplated getting home, they wondered if they would tell everything too fast or close up completely. Billie was generally verbose. He expected to be garrulous with his family.6

Billie's plan was to fill every minute. His brother Howard told sister Elsie in 1918, no doubt recalling Billie's attitude, that it was the change that counted: ‘it does not matter if you do yourself to a frazzle as long as you have heaps of things to think of the next few months’. Billie's six days in December 1915 were hectic. It was ‘topping’ visiting his old school, Dover College and seeing how his brother Tom loved it there. He saw a new play in the West End called Bric-a-Brac and caught up with plenty of relations. He was pleased he did not spend too much money: ‘yet we didn't exactly skimp, but, Mother, you paid a lot too much’. Don't let that occur again, please was Billie's reprimand. But Mrs Nevill's affectionate largesse for those few short days was totally understandable.7

His first leave made Billie more confident that the family were coping without him and would continue to do so. His letters became less frequent, and shorter: ‘there doesn't seem the need to keep you disalarmed about me now … you know I am permanently alright’. Billie looked forward to his spring leave in 1916 immensely. He hoped for nine full days this time, warning ‘don't let too many relations know’. The 6.15 from Amiens to Boulogne, then Folkestone, then Victoria. Billie set out the timetable in a hurried note on 26 April. ‘Blighty,’ he sighed in expectation, ‘oh Blighty, in about a week.’

But Billie in fact enjoyed his spring leave less than he had done his winter one. His teeth had become a nightmare. The dentist's ministrations, completed in far too much of a hurry, had, it was believed, given the East Surreys a secret weapon. Billie's new death's head grimace when he smiled would, it was reckoned, finish off any Boche encountered in the enemy lines. Sadly his relationship, expected to turn into marriage, with Muff Schooling collapsed on this leave under the strain of separation. The best of it was his time with Howard, also on leave from the Front. They went off together to buy the footballs for the Big Push everyone knew was coming soon.8

Lance Spicer, like Billie, was jolted into constructive planning by the start of a rota in his regiment. The allocation of time, eight days in all – effectively six clear days in England – set his mind racing with plans for a dash to Edinburgh to see a brother and sister. ‘I think I should go a burst and have a sleeper,’ he decided, reckoning on saving travelling time to allow more social time. His good spirits when it was over suggest that Lance's leave was highly restorative. Of course ‘the time was all too short’, he wrote in February 1916. But he was emphatic about having ‘enjoyed my leave enormously’ and ‘living on sweet memories’. An hour by hour account of the journey back was a necessary exercise in acclimatisation. In the weeks when the Somme battle raged, Lance yearned for another leave but he became philosophical about its not coming his way. Largely due to a shortage of officers, it was ‘a complete and utter washout’, he confessed in August 1916. He consoled himself by reflecting that fortunately he was then serving ‘in a very quiet part of the line’.9

Those with small children had the profoundly moving experience of seeing how they had developed. They had to come to terms with the fact that they were missing this period in their young lives completely. Sometimes this made adjustment afterwards difficult. Charlie May reflected in his diary on ten days of ‘utter unalloyed happiness’ in February 1916 with his wife Maud and daughter Pauline. It was so soon over, ‘like a dream’. The shelling he returned to seemed unreal. The contrast between trench conditions and his clean and comfortable home was almost unbearable. Four days back in the trenches he confessed to feeling that his leave had ‘been with me awfully strongly till I have felt quite humpy and fed up’. He longed to see the ‘bally war won’.10

Rowland Feilding was to and fro to France throughout the Great War, both because he kept sustaining minor injuries and on the regular leave he was permitted as a senior officer. He spent a few days with his family in August 1915 and again in September. After a period of heavy responsibility during the Battle of Loos he was again home, for a week this time, in late October. He hurried down to Devon to visit two of his daughters, Joan and Anita, at their boarding school in Sidmouth. In December, he was invalided home with a badly infected knee which kept him incapacitated until the following March. ‘The sea was like glass,’ he wrote to Edith, describing his journey back to the Front in April, ‘the scene was very picturesque and rather spectral as our ship lay to, outside the great submarine net, waiting for darkness before setting out.’

Rowland had left Edith pregnant, and his fourth daughter was born in October 1916. It was his sister-in-law who found the time to send a full account of the baby. Joan, at twelve years old, was besotted, telling her father, in a ‘delicious’ letter, that ‘so far she had only seen Pru with her eyes shut’. A week later, replying to her, he confessed he was ‘simply pining’ to see the new baby: ‘what a lovely baby Prunella sounds from your description. I hope she will keep her blue eyes.’ Three weeks later he was back home in Gordon Place, Kensington drinking in the sight of his new daughter. Another decent three-week period of leave followed in March 1917. A broken hand and fractured rib in a riding accident brought him home again in July for two months. Then he fell and dislocated his elbow when leading an attack in March 1918. He had chloroform twice before his elbow was put right in the field hospital, then needed weeks in a hospital in Park Lane, before returning for a final spell of active service in August 1918. Rowland's was an adventurous war. He was a great survivor.11

There were some senior officers who, utterly absorbed in their work, had real difficulty about taking leave. Ethel Hermon, pregnant and missing him, began pressing Robert to get home in August 1915. ‘I will come as soon as I can,’ he pleaded, ‘of course all this is dependent on what the Boche does to us or we to him.’ He felt tied by ‘such an exceptionally good lot, both of officers and men’, who ‘so absolutely trust one and look up to me to do the right thing’ that he was finding it hard to get away. Then Loos intervened. Robert decided to send his servant Buxton home in his place to reassure Ethel that he was ‘fit and well’. He would tell her all the news and ‘buck like steam’: ‘I wish I was in Buxton's shoes but it is quite impossible just now as I have so much doing … believe about one eighth of what he tells you.’ Buxton received credit from Ethel for not grousing, but he went beyond his appointed role by announcing the war would be over by Christmas 1915. ‘I don't see how it can be,’ Robert wrote, hastening to disabuse her. He suggested it could be May 1916 before the Germans ‘came tumbling home very much faster than they went out’.

Robert was thinking about his wife's coming confinement and assumed they would have a second son. They agreed his name for the present should be Benjamin. He arranged for a fur coat to be sent from a London store, reckoning that if Ethel wore it at once ‘both of you could benefit by it’. Their fifth child, who was a son, was born on 11 November but it was two days later that Robert heard the news. ‘The glorious news dawned’ on him when Buxton brought him a wire in the middle of mess dinner. ‘The new moon is shining in an absolutely cloudless starlit sky and the whole world seems at peace,’ Robert wrote, describing his mood that evening, ‘there isn't a gun firing and if Ben wanted a better augury he couldn't possibly have it.’ He was the happiest man in France and would be home in just a fortnight.

Meanwhile the children's reports poured in. Betsy said Benjamin had ‘lots and lots of hair for his age’ and ‘it is a very dark baby’. But sometimes, she had heard, ‘dark babies turn fair’. ‘I expect they have nearly torn him to bits by now in their anxiety to hold him,’ Robert told Ethel, adding ‘I expect you are feeling as proud as an old Peahen’ to have produced a fifth child. Even Tom Woolven, Robert's gardener at Brook Hill, sent a congratulatory letter. The mess became a distraction. Robert needed peace to communicate his deepest thoughts about women's bravery: ‘not a word of all your pain and your nice cheery card a few hours afterwards’. His emotions were stirred and hard to handle. ‘I am very tired of this life apart,’ he had written earlier. But now there was more fruit from his loins; and another boy, too.12

Leave boats were now sailing from Le Havre to Southampton, a journey in darkness to avoid German submarines, which took thirty-six hours. The Hermons christened the child Kenneth Edward, not Benjamin, during that leave, so the baby shared his initials with Robert's regiment the King Edward's Horse. The Armistice on his third birthday, though they did not know it, still lay well off during that blissful period of family reunion in the Sussex countryside. Robert was devastated that his manly reserve broke down at his departure. He dared not open a note Ethel gave him containing a four-leafed clover, but thrust it straight in his pocket. He explained in a letter from Southampton ‘I was sorry I was so stupid and just broke down for a minute … I couldn't have read a message from you and then said goodbye to the kids afterwards without breaking down.’ ‘You say it was hard going before,’ he wrote, ‘but this dearie beats anything.’

Two days later, Robert confessed to ‘a large aching void, Lassie mine, which will take a lot of filling’. But he believed that his ‘lovely time at home ending with Ben's nice little service’ would last him some time. He had not yet got used to the name ‘Kenneth’. Ethel scanned his letters for hints of depression. Emotionally he was at home, not in the mess at Vaudricourt that Christmas. He came clean in a letter on Christmas Day in 1915: ‘I hardly dare think of your day at home and I can't write decently with other folk in the room.’ Four days later Robert confessed: ‘it has somehow been a bit of a job settling down again and it was really far easier going before than it was this time … I think if I had stayed for Xmas I should never have come back at all.’

When Ethel spoke of his next leave in March 1916 Robert read her a stern letter in duty. Sixty-one NCOs and men in the squadron had been ‘out the whole time and not yet had leave’. He could not claim special stress to justify putting his need above theirs. ‘I want to get the original men home if possible before one goes again,’ he insisted. Yet by October he was ready to declare ‘I am heartily sick of having been away so long … I am afraid dearie it will be many weary months before we can do things together once more … the end is not in sight.’ He was both desperate to be back with her and the Chugs and could not bear the thought of another parting. Ethel had been writing about the possibility of a meeting in Paris. He dismissed her ‘low mind’ about this. He did get home for two weeks in October 1916. He agreed, presumably at Ethel's prompting, that they needed time for them to be just themselves. So they spent their last three days together in London, staying at the Berkeley Hotel. Ethel may have been suffering from premonitions of losing him.13

Leave was much associated in everyone's mind with sex, the most severe deprivation of military life, for many not easily resolved by available French country girls. Lieutenant General Hacking, inspecting the Royal Welch Fusiliers in 1916, ‘chatted and chaffed’, it was noted, ‘pinched their arms and ears’, as he passed along the line and asked ‘how many children they had and if they could be doing with leave to get another’.14 Reggie Trench, feeling increasingly sex starved in June 1917 after five months apart from Clare, told her that there was much talk of this in his mess. ‘The great excuse we young married officers want to give is “sexual starvation” – this would pass as far as Brigade with endorsements in favour of leave I'm sure but I doubt if it would get past Division.’ His campaign for leave had just begun in earnest, with his CO forwarding an application declaring ‘that this “zealous and energetic officer” should have the rest that leave entails’.15

When Reggie started thinking about leave that May his mind ran on his daughter, now just eighteen months old: ‘will she recognise me? and talk to me? … she must have a rocking horse soon mustn't she?’ Once it became clear that he might get his leave while Clare and Delle were having their long summer spell on the south coast, it took shape in his mind, in terms of sea, sand, paddling and bathing. ‘If the place is not too crowded we could bathe from some isolated cove along the shore,’ he suggested; ‘that would be much nicer than bathing with crowds of other people.’ When he heard they were settled at Charmouth on 3 July, he declared ‘it must be jolly’ there, ‘wishing there was a decent chance of getting down to you’.

Next day, leave seemed to be in the wind. ‘I'll be in Blighty by Tuesday noon,’ Reggie dreamed, ‘and with you for night ops that night!!!’ It was actually another ten days before Reggie was reunited with his family and then his mother joined them too in their lodgings at Charmouth. The photographs on the beach prove that this holiday was all they had dreamed about. When his leave was over, Clare travelled to London for their traumatic parting. Reggie was anxious till he had heard she was safely back in Dorset, where Delle's nurse had been tending the child.16

Clare's letters expressed disbelief that it was all over so quickly. ‘Yes Darling,’ he replied, ‘I feel that I can hardly realise that I was ever lying on the beach with you and Delle or undressing with you on that grass under the cliff – its all a lovely dream. Never mind we did have the time and it will come again one day.’ His great sorrow in his letters those next weeks was that Clare sent him no news of Delle welcoming a brother. He longed for a son. Another ten days’ leave at Christmas in 1917 enabled Reggie to visit relatives in Berkshire and Warwickshire.

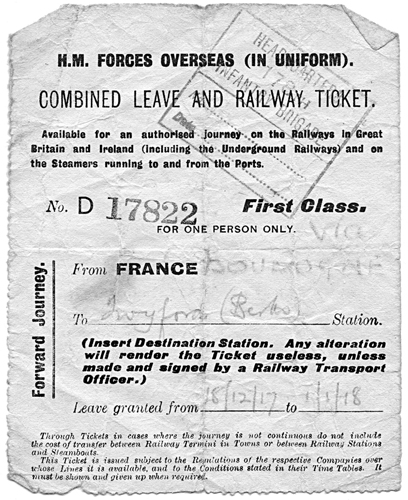

11. Reggie Trench's combined leave and railway ticket, 18 December 1917-1 January 1918, France to Twyford, Berks.

That Christmas leave he basked in his daughter's company: ‘Delle is looking so awfully pretty now – and of course talking much more than she used to.’ He sent his mother a little paper knife made by one of his pioneers, the handle from ‘a Boche cartridge case’, the blade from ‘a piece of brass shell case’. He was thrilled with Clare's present of ‘a ripping fur-lined “British Warm”, that is a short coat reaching to the knees’ with ‘a fine big collar of opossum that turns up right over one's ears’. Trying for a son was a preoccupation during those precious days. Writing on the journey back, Reggie reflected, using the nickname Clare gave him, ‘I think if we have a “Chennie” he will be quite fit as we are both so well – which is more than is always the case with men on leave’. But it was tough leaving home again. His account was clipped, concealing his massive emotions. ‘I hated saying goodbye,’ Reggie wrote, ‘but we had a jolly time together. It gets harder every time to say goodbye.’17

The Sherwood Foresters endured a long, hard winter. Temporarily in command of the battalion in February, Reggie was very aware that many of his officers and men were well overdue for Blighty leave. Tension was mounting with the expectation of a major German offensive. Everything possible was being done to meet it effectively. An Amiens pass became the best to be hoped for in those winter days. This in itself was a taste of bliss, so there was much competition for these passes. Simply to walk up and down the main street of Amiens, ‘a gay happy place untouched by the ravages of war, jostled by the throng on the Rue des Trois Cailloux, stopping here and there to look into picture shops or book shops, was a joy that made the long journey there in a dusty, bumpy lorry, a mere thing of no account’, recorded the battalion history. ‘I am sending officers and men in to Amiens every day,’ Reggie reported, ‘it does them good I think: any change is good for a man.’18

For two of our soldiers, falling in love and the pursuit of a love affair at home provided the emotional impetus to remain strong as a soldier at the Front. When Cyril Newman created the typescript version of his war correspondence he organised it around the ‘fiery ordeal’ of his initiation into trench warfare, his first leave in January 1916, the Somme, ‘second Blighty leave’ in July 1917 and the ‘Great German Attack’ from March to August 1918, when he eventually came home wounded. It was the sheer unbounded solace of his two periods of leave that made sense of his long war for Cyril.

Cyril used the diary he had kept during his 1916 leave to write the account he gave his children of the glorious week when, briefly at home, he was betrothed to their mother. Every detail of his excitement on the journey from Carnoy to Waterloo was still vivid in his memory many years later. It was strange walking in his uniform, leaving the station he knew well, passing city workers, on his way to visit his own workplace, the offices of the Official Receiver in Carey Street nearby. ‘I felt exalted, superior. The passers-by knew not of trench life … of the degradation of living in mud and dirt … hurrying along on their apparently purposeless pursuit of the daily means of existence – earthbound – muckrakers, missing the glory – the crown of self-sacrifice … not one stopped to enquire – was I from the front?’ Cyril's recollections encapsulate that mental gulf between the Home Front and the Western Front which historians are still trying to puzzle out.

It is much easier to understand the rising joy of Cyril's experiences as that day, 14 January 1916, went on, than his lonely walk from Waterloo to Carey Street. There was the office welcome, the friendly chat there, his City shave, shampoo and haircut, meeting Winnie who had been at her office, the bus journey to Muswell Hill, the reunions with his family and hers. Tea was mixed with tears of joy. Cyril could hardly eat at all those first days home, when he saw many friends he had missed for eighteen months and talked with his Sunday school boys. Visiting Winnie's home one morning, when she had obtained leave from her office job, he recorded that she ‘sang to me “Wonderful Love”, “Just the same” and “Rock of Ages”’.

Their betrothal was a formal matter. Cyril explained his prospects to Mr Blackburn with Winnie discreetly absenting herself. When her parents had agreed to the marriage, the couple knelt together in the Blackburns’ front room for her father's prayer for God's blessing upon them. Next morning Cyril and Winnie did the round of City jewellers, finding a ring they were happy with at Bravingtons in Ludgate Hill. On the day of his departure it was Cyril who sang in the Newmans’ front room. The hymns, which Winnie played as he sang them, were ‘God be with you till we meet again’ and ‘Blest be the tie that binds our hearts in human love’.

Their letters to each other after the desperate emotions of their sad parting at Waterloo were exercises in establishing, for Cyril and Winnie, the self-control they needed and the acceptance that the war would go on. After the family kisses at the station, Cyril noticed the train was pulling out. ‘Give me one more kiss,’ he pleaded with Winnie, then he ‘had to run to be pulled into the carriage’. Writing to Winnie's parents, Cyril confessed his ‘natural aversion’ to the whole way of life he was thrust back into, but he insisted that, at war, ‘by living for God I am best endeavouring to live worthy of Winnie and her love’. The next Sunday afternoon Cyril managed to escape for a long quiet walk to Sailly-Laurette, where he sat on a cart in a field. He could cry there quietly to himself. He told Winnie about this in one of his green envelope letters.19

By January 1917 it seemed an age since the eyes of these lovers had met. It was tantalising knowing that, as a Tommy, you could not expect to hear about your leave till the day before you went. The dream of visiting Winnie's sister at school in Essex, on the next leave, was focused for Cyril upon the notion of having her to himself most of a whole day: ‘we might have a carriage to ourselves both ways’. In April 1917, Cyril discovered he was about number thirty on his battalion list but he knew leave was often stopped, ‘owing to our or the enemy's activity’. In May, he was dreaming of a holiday with Winnie at the seaside: ‘what a ripping time we would have together … a daily swim in the morning – walks in the afternoon. And at least three times a day I should demand a kiss – morning, afternoon and evening’.

Winnie continued to badger him about when he would get this leave. Three men granted it in May 1917 had waited nineteen months, he reported. Then he heard: 15 to 25 July with nine clear days in Blighty. His diary is a blank on the details of how he spent his time but begins again with the return journey. It recaptures his feelings: ‘the cruel heart-breaking leave train has just brought me to this cruel place – Folkestone Rest Camp. My heart is numbed and burning tears are kept back only by strong effort.’

Cyril's record of an incident during his return journey reveals the hierarchy of the BEF and how this came across to one poor Tommy. He and two others were seeking to find their way to the battalion, untidy and bedraggled, when two Lancers passed them, escorting none other than General Haig, immaculately dressed.20 They saluted, he returned the salute. What a few words would have meant in that flat, bleak countryside, Cyril reflected, ‘if he had asked us who we were and whither we were wandering … how that story would have spread … but he was too lofty – too aloof – too proud – to take any interest in three riflemen’.21

Jack Sweeney explained to his pen-friend Ivy before his leave in May 1916 how shy he would be. He had even talked of putting his gas helmet on when he knocked at her door, ‘then you will not be able to see me blushing’. But she had sought to bolster his courage in advance: ‘I am so glad you are going to let me be your boy while I am on leave,’ Jack wrote on 2 May.

His leave was beyond Jack's wildest dreams. Ivy sought to put his mind at rest about his not being sufficiently educated for her. To his amazement, she ‘told him it didn't make any difference whatsoever’, as Ivy related years later. Ivy's father was more concerned about this issue than she was, ‘but soon became as fond of him as my mother’. When she plucked up courage to ask her mother about their going out to a show together, she was not surprised, knowing the mores of that time, to be told ‘you'll have to get Dad to take you’. So they went as a threesome to a variety show at the Coliseum. ‘But we had walks together,’ Ivy recalled, ‘and I saw him off at Waterloo.’ She gave him a kiss when they parted, ‘though I also gave a kiss to another soldier he was with’.

Too shy to declare himself on this leave, Jack did so when back at the Front. ‘Dear Ivy, I've fallen in love with you … I know if I cannot be your boy I will love you as a loving friend,’ he wrote. For her this was the most treasured of all his letters. When she replied positively, his confidence increased. ‘Well my Darling,’ he wrote on 23 June, ‘I am so glad that my letter did not offend you … but now I know and you have made me so happy I can fight out here now with a good heart knowing I am fighting for such a darling girl.’22

As Jack went through the Somme that year the correspondence blossomed. Towards the end of 1916, he was asserting ‘I am sure I shall not be shy next time I am home.’ He needed a month in Blighty, he insisted, but leave was a long time coming. ‘You might ask Lloyd George,’ he joked, ‘or ring him up on the buzzer.’ Ruefully, he noted that leave was coming round for his officers every three months but, with only six in his battalion going on leave each week, it was taking a year for Tommies to get a turn. ‘I only wish you would come and fetch me.’23 But then his luck did come up: he was sent on leave just before Passchendaele.

It was on this leave that Jack and Ivy became engaged. She had no hesitation at all in accepting, though they had spent just a few days together more than a year before. She felt she had really got to know him through their intense and incessant correspondence. Her parents fully approved, giving him the spare room as a mark of how they felt. The last evening, with the gramophone playing and Ivy's affectionate attention overwhelming him, made Jack sleep so well he almost missed the leave train. ‘I am glad that you did not cry dear,’ he reflected, dwelling on those last hours they had together, when he wrote from the Front, ‘but I must tell you dear that I was crying myself that morning I came downstairs past your room.’ Propriety prevented him from opening her door, ‘so I glanced into the drawing room at the spot where we sat the night before’. Just catching his train at Victoria, Jack ‘felt it when I saw the other boys with their girls on the platform, but still I wiped my eyes and fancied that you were there’. Jack related the reception his pals had given him: ‘some say lucky kid, others Poor Old Nobbler caught at last’. He guessed that what friendly Sergeant O'Brien would say when he saw him would be ‘tres bon, when's the wedding?’24

It took some while for the BEF to organise proper leave rotas. After all, with leave for two million men to be administered, just one week's leave in the year required the movement of around 40,000 men daily. As we have seen, the notion of an annual entitlement was not enforceable for all. When it did come up, going on leave meant entering a kind of limbo where disciplinary regulations were relaxed. But there was always tension. Leave trains were specially designated and famous for their missing doors and broken windows. There were canteens at the larger stations run by society women. At Folkestone men scrambled for seats on the London train. At Victoria men often received cigarettes and chocolate handed out by waiting crowds who welcomed them home.25

Many found leave hardly credible. It was difficult to adjust to Blighty, to home life and rich civilian food. Above all, it was the strangeness of being back in England which disconcerted men, though this was something they could only put their finger on much later. Because men did not write letters when they were at home, it would be easy for us to miss a crucial point about the double identity into which the Great War forced volunteers. Patrick Campbell, in his memoir In the Cannon's Mouth, published in 1979, wrote a short chapter which articulated the experience of leave many years afterwards very much more revealingly than anything written at the time.

The strangeness, he recalled, ‘began as soon as I was in the train at Folkestone’. He had been told that Ypres would seem like a bad dream when he got to London. But, on the contrary, ‘it seemed to me that London was the dream, Ypres and Potijze Road the reality’. The Thames Valley was familiar, ‘but for some reason it seemed less home-like now’. He was missing something. It was strange how much he thought about his friends whom he would not see for ten days. His parents harried him with questions; his sister laughed with him ‘but did not ask me questions about the war’. He could not help dwelling on the others, ‘wondering whose turn it was to go to the Observation Post and what the shelling had been like today’.

In an attempt to snap out of his identity crisis, Campbell took off his uniform and went into Oxford. But a corporal who knew him stopped to ask whether ‘I did not want to be out there with all the other lads’. He had forgotten his reply when he told the story decades later, but ‘a true answer would have been that I was already there, not here in the middle of Oxford’. His parents took him to Brighton, hoping he might forget the Front, but his pretty young cousin, who lived there, asked him what battle was like and if the Belgian girls were as pretty as English ones. ‘But she did not really want to know the answers and I did not want to tell her.’26

Leave always had a bittersweet tang. Letters cited in this account have hinted at the powerful emotions it induced, at the suddenness with which it began and ended, at the sense that it was baffling and almost inevitably disappointing in some way or another. Yet we have also seen how much it meant to individual soldiers, the importance of the brief experience of loving care for men living away from home in such demanding circumstances. Leave could be, despite everything, a temporary source of pure joy and exaltation.