‘Write as Often as You Can’

Letters and Parcels

Collections of letters take us into the private worlds of loved ones and the most intimate concerns of family life. Our soldiers were always in close touch with home. Letters used in this book express the sheer comfort to be obtained by writing to a member of the family. Thousands watched for the post in eager anticipation of a buff or green envelope with familiar handwriting. We have to read between the lines, perceiving the understanding and sensitivity with which the soldier's words would be greeted when the envelope was opened. Replying was a recognition of the massive encouragement that the bursting mailbags brought to the Front. ‘Write as often as you can. I long for letters now,’ Peter McGregor told his wife.1

Three of our soldiers rejoiced in well-settled marriages. Their broods of young children pored over paternal missives. Another large group were young men that were the oldest offspring of sizeable families, with siblings who looked up to them, admiring their courage in going to war. A few were not yet married but had sweethearts whose dedicated support, in the form of numerous letters and parcels, sustained their endurance. This was very much a family war. Men's emotions were always more than half left behind them in Britain. Crumpled pages filled soldiers’ pockets until, bulging out, they had to be replaced by new missives of love and care from across the Channel.

Rowland and Edith Feilding trusted each other completely. ‘I continue writing to you of all the dangers of the war,’ he confirmed in May 1917, ‘remembering that you once said that if I hid anything you would know it and only imagine worse things than were really happening.’ His 261 letters home are powerful testimony to the war as it was lived by a senior commander in the field. ‘Snowball’, with his shock of white hair, was a familiar and much-respected figure at the Front from 1915 to 1918.

The Feildings had three daughters. Fifteen times he wrote to his eldest Joan, who was ten at the outbreak of the war. She acted as a channel of communication with her sisters. She packed up candles to send him soon after he left for France. He sent her a German soldier's shoulder strap, booty he seized at the Hohenzollern Redoubt. When Edith told him about Joan's efforts at Auntie Agnes's bazaar, making £5 in all, he was proud of her. More solemnly, when his men were suffering in the freezing cold of the 1916 winter, he told his eldest girl to ‘remember what they are going through for you and pray for them’. The others were much in his mind too: ‘I use Anita's soap box every day,’ Rowland wrote gratefully, ‘and I carry Peggy's chocolate in my haversack to eat when I get hungry in the trenches.’ ‘I am sending each of you a poppy to put in your prayer books,’ he wrote in June 1915.

By 1917 Rowland had a fourth daughter. He thanked Joan in February for her latest letter: ‘I send four German postcards choose the one you like best and give the others to Anita, Peggy and Pru’. He thought he could guess which she would choose. He had found the postcards on a dead German. In October, he was back on the Somme, reporting ‘miles of devastation’ to Edith. ‘I rode through one of the flattened villages near here’, he told Joan. The church was ‘a mound of stones and dirt’ but, beside it, he found a great crucifix standing undamaged. ‘One sees that so often in France nowadays’, he explained.2

‘My pockets are so full of letters that I have to burn them,’ wrote Peter McGregor. ‘I've had a letter almost every day from you since I came here,’ he noted wonderingly on 2 July 1916. Margaret, ten years old, and Bob, who was nine that year, were every day in his thoughts. He lived for and fought for them. He treasured all Jen's news of the family's doings. Grannie McGregor, too generous, needed to limit her parcels. ‘I wonder if it would hurt Grannie's feelings,’ he asked, ‘if you told her not to send so many oatcakes. I am in one place for so short a time and to carry extra weight is just a bit too much for me.’ Peter was always full of gratitude. The sheer ardency of his love for Jen shines out of his letters. ‘I seem to love you deeper and better than I have ever done,’ he declared shortly before embarkation.3

Robert Hermon's letters to his wife Ethel were equally touching. He usually began ‘Darling Mine’ or ‘my dear old Lassie’. Before his leave in October 1916, he wrote 280 letters to her in reply to 303 she had sent him. He was easily disappointed when she missed a day, as on 23 May 1915, which brought ‘four from the Chugs which I liked very much’. His children were Mary, Bob, Meg and Betty (plate 17). His eldest boy and girl both wrote to him very frequently, amusing him by their spontaneous but chaotic spelling. Mairky sent him bullseyes; Meg cake and candles. When the children enclosed hairs from the dogs in an envelope, he kept them with his photos of them in his pocketbook.

It was almost unbearable when Ethel sent accounts of time on the beach at a rented holiday home near Worthing: ‘I would give anything to see the Chugs and you,’ he wrote, but he was ‘glad to hear my little Meggie is so brave in the sea’. He sent Bob a bayonet, rather a gruesome memento, he confessed, which he suggested should be ‘firmly nailed to the nursery wall’. Away from home Robert remained very much the paterfamilias. There was a controlling aspect to his correspondence. Betty shook the camera, spoiling some photos of the family. ‘Teach her to put it on a chair,’ resting it if possible, he advised. He was horrified by Lloyd George's suggestion that women should work in the munitions factories. This was for spinsters and widows: ‘your first duty to your country is the efficient upbringing of your children to be useful members of society,’ he told Ethel. But he consoled her when she had to see Bob off to boarding school for the first time on her own. After six months, Robert found himself ‘rather homesick’ and ‘just longing to be out of this wretched business’. ‘I hope all the doggies are well,’ he wrote plaintively. Accustomed to the life of a country squire, it had not been easy to come out of retirement.

The children were never far from his mind. ‘Would to God this damned war was over and we were together to pursue the even tenor of our ways with the little Chugs once more’, he declared in early 1916. A few weeks later, he sent Meg ‘a small birthday present of some French buttons worn by a soldier who gave his life for his country at Souchez’. When Ethel reported to him the children's enjoyment of a birthday party in the village, he reflected that they were ‘lucky to have so little knowledge of what is going on.… I look forward to the time when I can bring them out here and show them what war means’, he reflected, showing them the landscape around Loos. ‘They would never forget it’, he believed, peering uncertainly into the future of his world, ‘and perhaps later on when questions of conscription .€.€. cropped up it might be very useful for them to have seen it.’ Meanwhile he was ‘simply starving’ for a sight of them. ‘I think old Mairky's little pencil effort simply sweet and old Bet's ‘pres’ too’, he told Ethel.4

Reggie Trench's double correspondence is unique among these collections, containing 245 letters to his wife and 35 to his mother. The contrast in the tone of these letters is striking. To his mother Isabel he was factual and unemotional, like the little boy he had been when reporting from boarding school, but regaling her now with the domestic activities of his military life. Indeed he wrote once ‘I can tell you we are very like boys at school here and look forward to the mail with eagerness every day.’ He knew the power of her love and her need to support him. ‘A fortnightly parcel would be very welcome,’ he soon prompted, ‘chocolate, coffee, butterscotch, toffee … tinned fish, fruits and meats, potted meat, sardines, anything that will make a change in our diet’.5

To Clare he was above all a lover. He treated her incessant letters as texts, in replies which often took her news and queries point by point, creating an intimate conversation. He tried to write every day, explaining the reason when he was occasionally unable to.6 Their married life since early 1915, long delayed, had been blissfully happy; their daughter Delle was a precious bond (plate 30). Reggie's physical longing for Clare was somewhat alleviated by the scarf she sent him after he had been away three months. ‘It is quite priceless,’ he insisted, ‘I sleep in it every night and wind it round my head. The feel of it makes me dream of you, my love. I know it so well over your dear shoulders around your sweet neck.’

The scarf created Clare's presence in bed with him. It was ‘particularly comforting’, he confided in a moment of candour about his vulnerability, because he had ‘an empty tooth’ needing filling. Soon after returning from leave in 1917, Reggie stressed just how crucial Clare's letters were to his morale. ‘I can truly say that my whole day is made bright when I get a letter from you,’ he wrote, ‘it always feels as if I have had a talk with your sweet self when I have read your letter.’ In October Clare sent him her silhouette, the new form of photographic profile just in fashion in England. He was ecstatic: ‘it is a remarkable likeness – it stands opposite me now – standing on my pistol, leaning against my flask.’

On his leave Reggie and Clare organised the purchase of identical rings to be worn on corresponding fingers as symbols of their troth. Their little girl was always present in their letters. Clare plied Reggie with photos and word pictures of her activities. ‘I think they are quite perfect,’ he declared, thanking her for a ‘ripping’ consignment. He had mounted his favourites, he reported, calling them ‘The house that Mummie built’, ‘Dare I knock it down?’ and ‘Oh so careful’, which showed Delle walking in her bonnet and coat, her ‘eyes on the ground quite intent on her feet’. He sent suggestions, for example a rocking horse, for Christmas presents. He wanted her to have a donkey and cart; with ‘promotion to a pony perhaps when peace comes’. His was a caring, besotted fatherhood of the mind and imagination.7

Clare's parcels, carefully thought out, were a constant joy. An early one included porridge, shoes, cigarettes, soap and cocoa tablets. What about boxed kippers to provide variety at brekker on a fortnightly basis? Reggie suggested. Clare began supplying Reggie with alcohol, ranging from claret to curaçao and liqueur brandy, besides consignments of high-quality wines from her father's cellar. He was delighted to find that all this travelled well.8

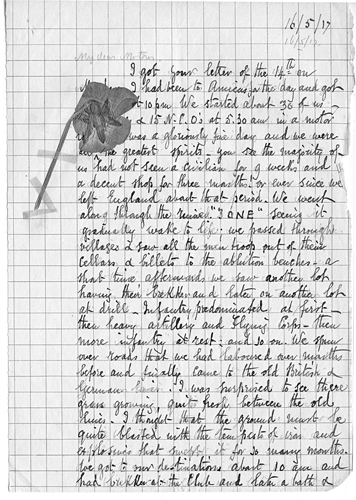

3. Letter from Reggie Trench to his mother with poppy attached, 16 April 1917.

There can have been few more energetic correspondents with a whole circle of relatives and friends than Cyril Newman. In the front line during April 1917, he counted his unanswered letters, finding 56 to which he owed replies. He asked his fiancée Winnie to explain to his six Sunday school boys and others at church the need to understand the impossibility of his writing as regularly as they did. He had sent off 66 postcards to friends the previous Christmas. But Winnie had to come first. When for a short time officers sought to limit letters to three a week, saving them time on censorship, he was quick with plans to evade this by enclosures in letters to his mother. His very emotional stability and strength depended upon contact with Winnie. His letter to her, almost without fail when time allowed, was the highlight of his day. He usually found something from her in the mail. When there was a gap caused by the vagaries of the post he pined: ‘four days without a letter from you seems so long a time’.

Chalking up fifteen months away in April 1917, Cyril yearned ‘if only I might see you again even for a few minutes, to hear your voice, to feel the touch of your hand’. This was another passionate love affair, recorded in 544 intimate letters between them which were later edited by Cyril. The difference between Cyril and Winnie and Reggie and Clare was that theirs was unconsummated desire. Everything that mattered lay in a wholly uncertain future. In Cyril's case, the entire war was an ordeal by fire. Over and over again, in one form of words or another, he described this crusade: ‘sweetest and best of women, Queen of my heart, accept the gratitude of my heart and the dedication of my life for all you have been and are to me’.

They had a running battle about the parcels Winnie sent. ‘How the other signallers enjoyed those oatcakes … will you thank your mother for the excellent cake and pudding,’ he wrote in the winter of 1916. But she was not to send another parcel ‘until I say so’. Cyril counted the costs of her normal correspondence, noting that each week she spent on him ‘at least one shilling and sixpence for papers and stamps’. Parcels on top of this ‘cost a lot of money and self-denial’.9

When Jack Sweeney went to France in 1914 he signed a will leaving all his belongings to his father. Not long at the Front, out of the blue, he received a parcel from Ivy Williams in Walthamstow. We know how she learnt his name. Jack's sister had a little boy in Ivy's Sunday school class, who had piped up when she asked if any of them had fathers in France ‘My Dad ain't, Miss, but my Uncle Jack is’. Jack Sweeney's archive is one of the outstanding collections in the Imperial War Museum, rivalling that of Cyril Newman in its size and emotive power. There are five volumes of letters, 878 pages in all, addressed to Miss Ivy Williams at 7 Maude Terrace in Walthamstow (plate 7).10 Like Cyril's, this is the record of a wartime love affair which ended in marriage and domestic happiness. Ivy must have told him a great deal in her letters about her household, her mum and dad and her siblings Olive, Florence, Frank and Charles. Jack constantly refers to them all. He felt that, by some miracle, a new family that cared about him had come into his life across the English Channel.

Jack fell in love with Ivy from a distance, well before he saw her face or even her photograph. She recalled in old age the day she came home from work in May 1916 and found him in their living room: ‘he was much quieter than I expected, gentle and with a lovely face … for him I think it was love at first sight. For me the real love came later.’ But their correspondence became increasingly intimate once they knew each other face to face. It meant a great deal to Jack that he was able to obtain a good supply of the green envelopes which Tommies used to escape the prying eyes of their officers. Fifty-seven of these green-envelope letters reached Ivy between December 1916 and the end of 1917. The standard declaration read ‘I certify on my honour that the contents of this envelope refer to nothing but private and family matters.’ Their love affair not only survived the war but also dissolved a class barrier, for Ivy's father was managing clerk in a firm of solicitors. She had been to technical college and worked as a solicitor's secretary. Their terraced home was a world apart from Jack's father's tenement flat. ‘Please remember that I am not a city clerk,’ Jack wrote in one of his early letters, deeply conscious of his humble origins and lack of education.

Julian Grenfell found solace at the Front in the loyalty of a hunting companion he met on leave called Flossie Garth. He carried her photograph when he went into action. His passion for her was undoubtedly primarily sexual but was at the same time, as letters to her in 1915 show, shot through with a mixture of bravado and macho dominance. He was both alarmed and fascinated by her reputation as ‘fast’. She needed ‘someone strong and capable with a strict sense of duty and morality’ to look after her, Julian insisted. It was obvious whom he had in mind. She needed ‘a good talking-to'; he would have to ‘get leave to come and administer it to you’. He plied her with requests for more riding photos, best of all with her buttocks ‘flying off the saddle’ as she jumped another brook.11

Every soldier needed a girl in his life who he knew adored him and believed in his chivalric quest. Men found romantic release in writing to the woman of their dreams. Yet many of our young soldiers were simply too young, too caught unawares by the war, to have acquired a regular girlfriend. A devoted mother was the next-best thing.

This was Graham Greenwell's saving grace during a tough period when the Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire Light Infantry held the Ovillers trenches eight weeks into the Battle of the Somme. Refusing to admit he was depressed or downhearted, Graham nevertheless stated that a letter, arriving ‘with the rations even up here, cheers me up tremendously’. Two days later he received his mother's ‘dear anxious letter’ about a small wound he had mentioned, not in itself very serious. A parcel came too, ‘containing – oh! sacred Joy! a Fuller's cake and some haversack chocolate which dropped like manna from Heaven in our midst’. On an evening when his headquarters was strewn with ‘five casualties together with a few shellshock cases’, the cake reposed incongruously as ‘a veritable Snow Queen’ among ‘the variegated litter’ of the dugout. In an earlier discussion of the items his mother might order in her Harrods parcels, he had remarked ‘I need not tell you what I want because you always know best and anticipate me’.12

The contrast between Graham's relaxed and confident relationship with his mother and Herbert Trench's anxious one with his mother Isabel is striking. Only two of Herbert's surviving twenty letters home were to his mother. Both were written in the first flush of adventure and bravado while twice crossing the Channel. He was the only officer aboard in July 1915. This allowed him to feel important. Placing guards at each end of the ship to watch for submarines, he made himself comfortable: ‘I grub with the captain and sleep in the saloon.’13

Many of our letter writers knew their stories would be devoured by a wide circle of family and friends. Billie Nevill's 203 letters home consistently show a cheery jauntiness. ‘Bill in Stillets’ he headed one after the previous one had begun ‘Still in Billets’, adding ‘please laugh’. This was schoolboy humour but then, like many going to war, Billie had just recently been a schoolboy. The inventiveness of the greetings which started his letters displayed his delight in family cohesion: ‘dear family and people all’, ‘cheer up family’, ‘everyone’, ‘anyone’, ‘cheer ho all’, ‘beloveds’ and ‘all and sundry whom it may concern’ were among his favourite formulations. Elsie, seventeen years older than him, was the closest to Billie of his three big sisters. When his Dover College friend Donald Campbell was sent home badly wounded, Billie quickly asked his mother and Elsie to visit him in hospital. Donald was thrilled, as Billie told the family: ‘I gather he likes you all very much.’ Thus soldiers drew men they cared about into newly created networks of friendship and support.

Mrs Nevill, more than ten years a widow by 1914, was the centre of Billie's emotional world. Her numerous parcels were meticulously packed. Besides these the family arranged regular Fortnum & Mason consignments which went down very well with Billie's colleagues. ‘May I take this opportunity,’ Billie told her once, ‘of saying how splendid you are in sending out exactly what I ask for and not something you thought would perhaps do.’ Mothers were the crucial trusted link between young men and their families. Among 5,000 letters written by unmarried men to their families now held by the Imperial War Museum almost half were addressed to a mother.14

Lance Spicer wrote man-to-man letters to his father which sometimes discussed the progress of the war. He was more intimate as well as reassuring, ready to show his softer side, to his mother. His tummy ache was quite recovered, he reported in November 1915, thanking her for her enquiry. He held too much food and ‘too little actual walking exercise responsible’. This letter gave her a cheerful account of the state of his trenches. ‘The army makes us experts in strange things,’ he reflected. ‘I have become quite a drainage expert.’

Suffering the blow of losing all his kit in the chaos of Loos, Lance confessed how essential letters were to sustaining his confidence: ‘I must say I have never appreciated letters more in all my life than I do out here and I know everybody says the same.’ He was thrilled with the new Gillette razor his sister Marion had packed up. This was ‘so beautiful that I hardly dared shave with it this morning’. But he did so, greatly boosting himself by the smooth face it revealed. The results of his shave, Lance was emphatic, restored his self-esteem. The razor brought a real sense of how he was cared for.15

Loos was also Yvo Charteris's baptism of fire. He tried hard to write to everyone back at Stanway. Mama, Papa and his sisters all had news from him in September and early October 1915. He was always cheerful, enjoying the spectacle of war with childlike innocence, as his regiment marched towards the ruined town. ‘The march was very thrilling,’ Yvo declared, as ‘the guns grew louder and the flashes more distinct’. He congratulated Mama on ‘a very skilfully chosen parcel of food-stuffs’, which included much-appreciated partridges. But, so incredibly young, he was inevitably needy. ‘Please send me some pencils soon,’ he asked Mary. ‘Write to me again,’ he implored his youngest sister ‘darling Bibs’.16

Ernest Smith's first letters show him setting up an effective personal support system. ‘I am going to give you a list of things which I should very much like at your convenience,’ he told his mother. This included carbolic soap ‘or something powerful’, matches, handkerchiefs, shirts and envelopes. Sisters Gracie and Sybil were making mufflers which he was sure would turn out ‘the warmest things that ever happened’. Calling his brother ‘my dear old man’, Ernest gave him an account of a Royal Engineers officer listening to German voices as he tunnelled close to them, which might have been taken from an adventure story. He thanked Aminda for her cakes and tobacco. His three sisters were soon plying him with butterscotch. ‘Thank you so much for your funny little letter and the lovely parcels!’ he wrote to Gracie in September 1915.17

That kind of regular and dependable family support did not come quickly enough for seventeen-year-old Wilbert Spencer. During December 1914, it sank in that his fantasy of the war being over for Christmas was just that. He had received one parcel and no letters for weeks, he told his mother on 26 December. He longed for cigarettes. ‘Please give Baby something from me,’ he pleaded, clinging to his big brother status. With too much expected of him so young, Wilbert needed a touch of regression. ‘MUCH LOVE AND HEAPS OF HUGS FROM BOOBA’ he wrote to baby Helen in capital letters. But parcels did soon pick up. He could not carry anything more, Wilbert explained in January. Chocolate, cigarettes and acid drops, immediate dope, were the best things to send. There was comfort in sending home photos. He felt the one in his waders, intended to comfort his mother, was quite good of him. Wilbert noted receiving his fifteenth parcel in February 1915.18

Older boys at the Front sought to be protective and encouraging to younger brothers. Billie wrote affectionately to Tom still at Dover College. ‘Go in for everything,’ he urged with regard to sports, ‘don't be shy of entering for things and don't overtrain to start with.’ Tom collected butterflies so Billie sent him specimens from France. Will Streets urged on his brother Ben who was taking singing lessons and planned a public performance: ‘you have to put your soul into music to succeed. Study hard, lad, and when I return I hope to hear you sing.’19 Alec Reader promised his brother Arthur, three years younger, ‘you will end up by doing great things’. There was inevitably some bravado in his account. His pal had ‘stopped a bit with his leg’ and was ‘now in England’. But things would get back to normal before his birthday came round in September, Alec assured Arthur. Then they would have a spree just like old times.20

Alec Reader struggling to cope, still only eighteen when he reached the Front, never really pretended he was happy. But he did have massive and persistent family support. Grandparents and aunts are frequently mentioned in his letters as well as his brother and sisters. So he managed to show a certain grim sense of humour. Writing once, after endless days of digging, he declared he would one day answer the question ‘What did you do in the Great War, Daddy?’ with the response ‘Dug up half France, Sonny’.21

‘It is wonderful how people think of one,’ Ernest Smith marvelled soon after landing. ‘I have received letters from all kinds of people.’ The unexpected letters from acquaintances back home meant as much as those of familiar family correspondents. Cyril Newman commented to Winnie on hearing from Mr Stewart, an assistant cashier at the Official Receiver's Department, his workplace in London. He had got up at 4 a.m. to see Cyril off when he was returning from his leave on a cheerless morning, ‘a side-whiskered man, you may remember him’. This lowly office colleague, Cyril reported, wrote of them all being ‘tried in the fire’. The letter confirmed his conviction that ‘we out here and dear ones at home’ stood shoulder to shoulder in the patriotic struggle.22 The immeasurable courage and persistence that mountains of letters brought British soldiers is summarised in such examples.

Men leaving behind a male, however young, found comfort by projecting on to him their absent household role. ‘Tell Bob to write one of his stories to me,’ Peter McGregor wrote to Jen, ‘tell him I don't forget him – he is looking after you and Margaret – I asked him to do all this – poor wee chap.’ Husband, protector, caring spouse – Peter mentally loaded everything on little Bob's shoulders. His schoolboy son bore his mantle of family and public duty. ‘Tell Bob to have a good term,’ he wrote, ‘not to be shy – soldiers always seem to be enjoying themselves and laughing – Bob wouldn't have to be shy here.’ Bob would surely one day live up to him at war too.23

Men at war quite evidently remained engrossed in the lives of their families and friends.24 They did not for one moment neglect their duty and love towards wives standing in for them. When in Zeppelin raids on London with bombs falling nearby, Edith Feilding explained how she kept the children entertained with games in the cellar, Rowland was full of praise. ‘I admire the way in which you have never woken the children till, in your opinion, the danger has become imminent … you are becoming a veteran now and I have every faith in your leadership.’25 Ethel should realise that danger from Zeppelins was negligible in rural Cowfold, though, Robert Hermon advised his wife. Anyway it was ‘infra dig’ to ‘go diving about in the cellar when so many in the village haven't got a cellar’.

Robert was more sympathetic to Ethel's sorrowful tale of seeing Bobbo off to boarding school. ‘I was so very sorry for you old dear and that I wasn't there to help you through … I was so glad that the old boy was so brave.’ Little Mairky had gone in the car to comfort her brother. The whole story, he confessed, his emotions suddenly collapsing, ‘brings home so close and makes one long so for another glimpse of you all’. In his next letter, fully recovered, he was back to planning Bobbo's entry to Eton in 1920.26

Sons at the Front naturally thought too about their own fathers, who although beyond service age were still the family breadwinners. ‘How is Dad,’ asked Will Streets, ‘working hard for nothing as usual down the pit?’ He thanked two of his brothers for their letters and apologised for not writing to them and his father separately due to lack of time.27 In October 1915, Ernest Smith thanked his father for a copy of his latest pamphlet about his system of muscular training for pianists, a somewhat risky business venture. He was glad ‘the summer has been well tidied over’ and hoped for ‘yet better business’ that winter.28

There was always solace in the mental escape that caring about a sweetheart's day-to-day life could bring. Reggie Trench regularly pondered Clare's stresses in her work in the Orpington VAD hospital. He was rooting for her promotion, knowing her dedication, so the news that she had been passed over for a senior post was disappointing. ‘It is very annoying Pet,’ he wrote, ‘after all the trouble you have taken and all the time you have spent there.’ But some months later he was thrilled by the account of her cross-dressing role in the hospital's music hall for her wounded patients: ‘I would love to see your acting … I wonder which pair of breeches of mine you have got hold of?’29 Cyril Newman's letters endlessly commented on Winnie's daily activities. He liked to know exactly where she was going to be every day. Thus, on 17 June 1917, he insisted ‘I do hope and pray that you will have a good holiday at Haslemere’. He wanted her to let him know about it later on but to take a rest first, ‘even from letter-writing’.30

The soldier's life was a long-endured act of defence of family and friends. Men at the Front worried ceaselessly how best to reassure those at home. Aware of the terrible tales of battle and casualties in the British press, they knew how much contact meant. This is why collections of letters are full of the faded field postcards which – with their option of crossing out all items except ‘I am quite well’ – could bring some balm when the postman called. Everyone seems to have sent them.

Reggie Trench's letters to his mother brimmed with reassurance about his living conditions. Typically, he enumerated his comforts in a letter on 16 April 1917: his fleece-lined trench coat which could be scraped with a knife when the mud became too thick, a visit from an officer who brought a bottle of port which they drank from enamel mugs, a ‘good comfortable dug-out quite dry and warm’, a hot bath ‘in half a German beer barrel’. Some of the colour remains on the purple pansy he chose to attach to a letter to Isabel Trench a few weeks later, a mute symbol for almost a century of his defiance of mud and dirt. In June, after a chatty account of trench life he added a PS to his valediction as her ‘loving son’. ‘I am extraordinarily fit.’ Isabel, writing over his pencil words as she did with all his letters, has added her own words of gratitude for this missive: ‘my precious son’.

There was nothing Reggie liked more than providing a colourful account of his domestic environment, if possible with lighter touches, as well as references to roofs of elephant iron and earth benches. ‘A blue and white little cloth’ he had found in Amiens, with flowers on the table in empty fruit jars was one such vignette. Even when he landed on a previous battleground scarred by shell holes and deep in mud, Reggie made something positive of his quarters, describing ‘a little hut covered with sandbags’ and a trench railway past his door as ‘an excellent billet’.

4. Field postcard, Reggie Trench to Clare Trench, 4 April 1917.

Reggie was equally solicitous to Clare. Once in the early days he let himself get depressed after being kept awake by messages and cold. But, by confessing it to her, he was able to stress how this was a break with his usual strong morale. Responsibility for 250 men prevented one ‘thinking too much of oneself. We are really happy,’ he summarised, ‘we grumble at the discomforts and we all share alike in every officers’ mess and don't do at all badly’.31

Cyril Newman warned Winnie whenever he saw on the horizon a difficult period for writing. ‘Only become anxious after a lapse of three weeks,’ he emphasised. During battle it was only the most determined soldiers from the ranks who found ways of getting a friendly officer to see a letter was posted. ‘You know that during the Somme period no letters were officially possible for a fortnight yet I managed to get one or two through to you,’ Cyril boasted to Winnie later. His carefully edited correspondence reveals the detail of this. He managed a brief note confirming he was safe and well on 4 July and a fuller ‘green envelope’, brimming with intimacy and affection, the same evening. The battle for Combles between 13 and 26 September was a period of ‘indescribable horror’, but Cyril managed to persuade Major O'Shea to send three letters with the ration transport returning back behind the lines. Many soldiers were less dogged about maintaining such scrupulous contact.32

Soldiers constantly worried over how much to come clean about and what to conceal. At times it was difficult to avoid entirely the rigours of military life. Graham Greenwell confessed he was struggling against bitter cold in the 1916 winter. The hard frost, he tried to insist, was ‘rather fun’ but woe betide them when the thaw came. He was clinging to the prospect of four days behind the lines, ‘motor drives’ to local towns and ‘some dinner parties’. ‘So you see I am fairly cheerful,’ he concluded, then, checking himself against looking pathetic, he wrote ‘I mean very cheerful’.33

The Nevill family, much as they loved Billie, knew the kind of reckless character he was so he was not disconcerted when his protestations about his safety were blown apart in September 1915. Some of the wounded East Surreys in hospital near home talked to a nurse about his bravado. This got back to the family. ‘Of course it is all rot about my being too venturesome,’ he insisted. He simply had to do his leadership duty: he would not tell anyone to look over the parapet ‘without doing so myself and, if necessary … talking to them a minute or two till they get confidence’. This care of his men he saw as ‘nothing at all’. ‘My invariable rule,’ Billie wrote later, ‘is unless you are directly helping to kill a German don't run the tiniest chance of getting killed by a German.’

In October 1915, the biggest German mine on the Western Front so far exploded close to Billie. Through his swift action and that of his fellow officers, the casualties were ‘pretty light’ but he had never ‘been in such a tight corner before’. Pleased with his performance, Billie could not resist telling the whole story, giving it weight by comparing the tongue of flame to ‘that big clump of trees in the bottom of Marble Hill Park’ near their home. Significantly, though, he began this long letter by confessing how he had pondered whether to reveal what happened at all. He was doing so ‘as you've been so good about not getting nervous about me’.34

Providing honest matter-of-fact accounts of performance yet making light of the worst aspects of trench warfare, soldiers were walking a tightrope. Emotions slipped out; hints of the strain they were under marked the most thoughtfully constructed letters. For there was sometimes a desperate wish and need to tell.35 Ernest Smith had done a pretty good job for four months in the line preventing his family from being alarmed. Then his colleague Ford went on leave and visited them in Muswell Hill. In a sense this was a relief, because he saw that he needed to moderate his descriptions of trench life in view of what he found the Smiths could take. ‘No doubt Ford gave you graphic details of the working parties we had to take up to the front line at the time he left us,’ he told his mother. ‘I was quite glad’ to get that over, he confessed. That was enough from him on the subject.36

Alec Reader, we have seen, constructed elaborate plans for reassurance. But once in the line his offer to write every week looked more problematic. It would be ‘as near Mondays as I can’, he declared, completing a very long letter from Le Havre. He did his best to stick to this, reproving his mother when she fussed about whether he was coping. Nevertheless, Alec's disintegration during his first months in the trenches is vividly apparent in his letters. He progressively abandoned his determination to protect his family from the full truth about his state of mind. By 4 May 1916 demoralisation had got the better of him. ‘I have undergone the various emotions caused by war, have seen most things that happen in war and don't think much of it.’ He had ‘seen men killed and wounded and have had to carry a mortally wounded man to the dressing station on a stretcher … the poor chap was dying fast and knew it. It was awful … war is a rotten game.’ But a few days later he was racked with guilt about this letter. It followed a particularly horrible spell in the front line, he insisted: ‘don't take any notice as we all have our rotten moments’.

With his mother's anxiety at fever pitch later that month and press reports of his Division's being almost wiped out, it must have cheered her to hear that Alec had spent four days in hospital after a minor wound and was then in rest camp. At the end of June he reported he had still not fired a shot. When he was told he could leave service because he was still under age there was no chance to consult his family. ‘The temptation to get out of this ghastly business,’ he confessed, ‘is far greater than you can possibly conceive, but of course there's only one decent thing for me to do, that is to stay here, but oh! it's going to be very hard.’ He reiterated this decision, using the usual euphemism, to ‘stick it out here until I get knocked out’ a week later.

Manfully, Alec decided that his survival depended on the war being quickly over. So he began to offer a new kind of reassurance. The war could not last ‘longer than August’, he declared on 8 July 1915; he was ‘absolutely sure’, he insisted on the 22nd, peace would come by Christmas, ‘so make a lot of puddings’. Two possibilities of escape held back his creeping fatalism: that his dad, now in service, would arrange a transfer or he would get a ‘blighty one’ a minor wound that sent him home. His mother still talked ‘all that bosh about bravery’. But, ‘horribly fed up with this game’, he admitted he was now ‘only too pleased’ for his father to rescue him since he could not rescue himself. Caught in a trap between his mother's feverish concern and his sense of duty, he was unable to resolve this. As his fatalism took hold, the censor's pencil began to run through many of the passages he wrote home.37

In Jack Sweeney's first letters to Ivy Williams there was much less inhibition than normal since this was a new relationship and he was testing the ground. His very first letter, sent to ‘my dear friends’ in July 1915, painted a lurid picture of Ypres as ‘a heap of ruins with dead civilians and soldiers everywhere’. He used hearsay to illustrate his case that Tommies dreaded going there: ‘anywhere except there is the cry’. ‘You will think me a lively feller telling you this but I do like to speak my mind.’ Yet, anxious about Ivy's reaction, his next letter was apologetic about his honesty: ‘I was wild with myself afterwards because I wrote such horrible stuff.’ Jack gradually came to see that trust depended upon some guarding of his tongue. But his fourteen-page account of battle the following April spared the girlfriend he had still not met very little indeed. ‘I am sure this war will send us all mad,’ he summarised: ‘people at home cannot realise what the lads out here go through.’

Jack battled through the Somme having declared his love for Ivy after his leave in May 1916. He was one of 435 men out of 1,150 in the Lincolns who survived, he told her in his account of the Big Push. Jack now regularly let his emotions show, confident in the intimacy which gave him daily strength. It was the censor who checked him, erasing his saying he feared he would be killed in the next assault on 10 September, but doing so rather ineffectually. ‘Keep smiling, enjoy your holidays,’ he wrote in the same letter, veering between personal fatalism and cheery encouragement to those back home.

It was November before Jack, still reliving it, began revealing to Ivy his personal story of the Somme. Fearing bad dreams if he let himself recount the experience of Mametz Wood, Jack decided ‘it is too horrible to mention’. But on 6 November he felt an overwhelming need to confide a crisis he had survived nearly two months earlier: ‘I was wet to the skin, no overcoat … I had about three inches of clay clinging to my clothes and it was cold … do you know what I did – I sat down in the mud and cried. I do not think I have cried like I did that night since I was a child.’ Then, soon after this, Jack let himself go and had a good moan on paper, which Ivy found it hard to take. He replied, ‘but I really was fed up at the time. I am so sorry that you get downhearted.’38

Older men might be but were not necessarily more open than younger ones. Rowland Feilding, we have seen, had a close understanding with his wife Edith.39 Peter McGregor was also middle-aged but had been flung into war, whereas Rowland had years in the army behind him. Peter was entirely candid and uninhibited with his wife Jen because, feeling in desperate straits, he often needed to be. Moving up to the Front in June 1916, he had to purge himself of the sights he passed through by getting them on to paper. A ruined town ‘made me shiver – wooden crosses on the roadside and in places in the town marking the heroes’ death – what devastation – a day of judgement more like’. He found it helped him to recount the gradual mastery of his fear. ‘Dodging rum jars, bombs, has become quite an art with me,’ he told Jen, ‘I can look back on the experience with amusement now but at the moment the agony of fear is awful.’40

Yet it was the young men who undoubtedly found writing home about violence and disturbing events the most painful, since they had not had time to acquire an adult armour against life's traumas. Wilbert Spencer's letter to his mother about his first dose of shelling is instructive. One of his men was killed and four were wounded. A slip of the pencil dropped a clue to his confused feelings. ‘One of the worst parts of the war,’ he wrote, ‘is the sights one has to endure.’ No wonder he was traumatised when writing this letter: he was recalling his care of the man who died: ‘the fellow who was killed lived his last minutes with his head on my knee’. He was thankful, he related, that men in this case were ‘usually unconscious and can suffer little pain’.41

One of the most difficult letters Ernest Smith had to write to his mother followed a three-day battle fought by the Buffs soon after he joined the regiment. On 13 August 1915 he was recovering from ‘a bit of a nerve shaking’, hunger and thirst. He explained that, at the time, ‘the sense of having to see after others and set an example prevents one from thinking much’. This was why he had difficulty in recalling much about the first hours of the show, when the Buffs consolidated a position won by another regiment, repairing trenches, burying the dead and helping the wounded. ‘The taking over of that line,’ he concluded, ‘seemed an unreal sort of dream to me.’ ‘I am not going into details,’ he announced.

Ernest could not stand the introspection involved in writing a detailed narrative of the battle, but what he did write powerfully conveyed his feelings. It also allowed his mother to understand what the experience meant for him three days later. It seemed, in Ernest's words, ‘as though there was an infinity of time and space separating us from anything beautiful or desirable and the weird effect was increased by the half light and mist, which prevented us from seeing very far or even distinguishing the Bosch lines’.42

What is remarkable about this letter is the delicacy of Ernest's balancing act. While emphasising the bravery of fellow officers and the spirit of his men he downplayed his own role. He sought to check his mother's alarm, by insisting ‘you must not run away with the idea our losses were exceptionally heavy’. When he wrote again on 21 August, Ernest had read of her gratitude at his having written at such length. The account on the 13th, he assured her, had helped him come to terms with the battle on his second full day of rest: ‘I was longing to tell someone all about it.’ He did so in a way that effectively managed her emotional state as well as securing his own emotional stability.43

The assignment set the 2/5th Sherwood Foresters on 4 April 1917 was to take the hilltop village of Le Verguier on the Hindenburg Line, in broad daylight, using a flanking movement to attack where the Germans appeared weakest. Reggie Trench led the third of three companies which swept down a long hillside in the early morning, meeting sustained and accurate machine-gun fire. Only 150 men reached the comparative safety of some dead ground in a hollow before the village. Reggie became the senior officer left in the action. He halted his men, too weak to move into the planned attack and unable to retreat. They were saved by a snowstorm, which turned during the morning into a blizzard, depriving the German gunners of the chance to set their sights. Under this cover the survivors got back and the stretcher-bearers laboured long and hard to bring in the dead and wounded. When the count was made the casualty figure, in a battalion whose fighting strength had stood at around 600, was 104, including 20 men killed.

So what of all this could Reggie relate to his wife and mother? Clearly he found it hard to write about his first battle. His letter next day opened with a full account of his makeshift company headquarters where, he asserted, all was ‘snug and cosy’, with a wooden and felt roof that kept out the worst of the snow and ‘a big fire going all night’. Coming to the failed attack, he confessed ‘I'm sorry to say that Captain Adams was killed.’ Then he wrote and crossed some words out. Next he spoke about how Milner, his subaltern, had been wounded, ‘a nice cushy one in the leg – he was awfully bucked!’ ‘One of my men was wounded for the fourth time,’ he continued.

There was nothing in this letter about how they had stood that morning at the burial, conducted by the much -respected Padre Judd, of most of the twenty men who had been killed. It was a lovely sunny day on 5 April. Reggie's clothes, soaked during the battle were drying out. But the last sentence of his report, in its sheer emotional force, set the rest of the letter he wrote aside. ‘I am thankful to say,’ he stated, ‘my nerves under fire are perfect – this is very comforting as one's responsibilities are very great.’

Clare read enough to realise the seriousness of the battle Reggie had been in. She at once pressed for more information. Two of her letters reached him in the same post on the 8th. Three days had given him a little more perspective. So after some chat about how nice it would be if she sent some dry kippers, since all her parcels had arrived in perfect condition, he responded to her clamouring. ‘Yes my love, I have been under fire and pretty heavy too – in that attack the other day their barrage caught us before we had started and they had a lot of machine guns too which did much damage. I lost some of my best men but thanks to a snowstorm was saved excessive damage.’

This time Reggie sought to reassure Clare that the battle had been an effective test of battalion morale. He was encouraged by his men's spirit: ‘the men were splendid – laughing all the time at their escapes and following their officers perfectly.’ Writing to his mother on 13 April, he felt strong enough to come clean about what had happened at Le Verguier. ‘We attacked a village – my company was forming the third line but there was only one line left after a little time and I was in that with those that were left. Poor old Adams, our company commander, was killed, such a good chap … I came through without a scratch and best of all – it was my first “action”. I found that my nerves were all right. My company did very well.’ The Sherwoods had won praise. ‘The GOC sent a most complimentary message to the “gallant fifth battalion”’, he told her.

Clare went on worrying. She was struggling to come to terms with what she had long expected: that her husband was now regularly in acute personal danger. A bundle of five letters received by Reggie on the 18th, written between the 7th and the 13th, dwelt on the battle and how little she knew of it. She was now fully aware it had been a ‘bad day’. He agreed, admitting ‘we had more casualties than I liked’. But it was only after another packet of her letters, on 25 April, that Reggie responded to her insistent pleading for information about his own escape from injury.

Three weeks after the battle, fourteen letters from him later, he at last told Clare how close that shave had been. He had been ‘a couple of yards from Adams when he was wounded – he died shortly after I believe though I had advanced and did not know till later’. She finally dragged the crucial information she wanted out of her husband. He had avoided telling too much, seeking to protect her, hoping she would not imagine how close he had come to death. But in the end his honour impelled him to tell the truth.44

Letters brought endless comfort, support and encouragement. In return soldiers offered involvement in the lives of those at home. But the attachment to home went deeper. Soldiers needed to confide their feelings about their homes. Thus nostalgia is a dominant emotion expressed in many of these letters. Men found the more stressful their situation became the greater their need for their homes as a heaven. Nostalgia distracted soldiers from the tedium of trench routine. At times it offered escape from anxieties that threatened to become intolerable. Emotional survival could be purchased by drawing upon the power of distant love.

When Robert and Ethel Hermon's wedding anniversary came round in January 1916, distracted by one of his best sergeants being killed that day, he forgot to think of her or write. ‘I'm awfully angry I forgot,’ he confessed. Keeping marital romance alive was hard work. Ethel had been teasing Robert about the early days of their love affair that month. He picked up her challenge to name what happened on a certain summer's day long before. He managed to guess she meant the day he proposed and was not instantly accepted. In a letter full of exclamation marks, he then teased her about a ‘day when you nearly chucked away a damned good bargain’.

Revealing how his hopes of leave were shattered that December, Robert asked Ethel to teach the children a prayer they knew which spoke of God watching over ‘the sentry on watch this night, that he may be alert’. In an elaborate imaginative exercise, he sought to draw Bobbo and his sisters into his leadership at the Front. ‘I would love to think that the kids were saying it or had said it when I go round the front lines at midnight’. The special appeal of this prayer for him was that he saw ‘so much of the sentry and know what he has to go through, with no protection against the weather bar what he can put on his body’.45

There was comfort in recalling family routines with happy memories; for example ‘Waste not want not’. Alec Reader reminded his mother about her reprimanding words across the kitchen table. Did she remember ‘the way I used to spread the butter and jam?’ Escaping into memory when he wrote to his father after his ‘pretty rotten time’ in May 1916, having just survived a ‘most unpleasant’ sally over the top, Alec's mind went back to their rides together on his motorbike in the English lanes. He was looking forward to their ‘spin on the Enfield’ on his return.46

‘As I came into the trenches last night,’ Rowland Feilding related to Edith on 11 June 1915, ‘the mud was just like very thick soup’. Whereas it impeded the work of his men, it lightened his mood to think of Anita and Peggy's childhood play. This, he joked, was ‘good mud wasted – how they would have loved it’. Peter McGregor's mind conjured up ‘the long stretches of sand’ at Burntisland, the Scottish resort where the family always took summer holidays. They were back there without him in August 1916. ‘How lovely it was,’ he mused, ‘I am sure you will be having a good time – how the kiddies will enjoy the sea and shore – how I long to be with you.’47

The reflective Charlie May, we have seen, liked to find time on his own when he could set aside the pressures of his company command in the 22nd Battalion of the Manchester Regiment. A ‘stroll out’ on Lizzie, his charger brought from England, written up afterwards in his diary, did much to restore his equanimity. He could lose himself in the landscape, daydreaming of his wife Maud and Pauline their baby girl. ‘I longed that you could have been with me,’ he recorded after a ride towards Canaples. Christmas made Charlie homesick, as he remembered the glorious family times of previous years: ‘how the lamps will gleam, the fire leap and the laughter ring’. He sat up with fellow officers, drank to absent friends ‘and thought pretty hard’. But at the New Year in 1916 he could not bring himself to join this throng. He needed time alone to immerse himself in ‘such sweet, sad memories’. Just after midnight a shooting star he saw cross the heavens seemed ‘a good omen for our future New Years’. His diary was a haven for Charlie May just as letter writing was for others. As the Somme offensive drew near, he drew strength, he noted, from Maud's regular and ‘ripping’ letters. In quiet moments he let his mind wander to her word pictures of their daughter. ‘Peace, comfort, all that is sweet clean’ overwhelmed him when he allowed these thoughts of her full rein.48

Reggie Trench permitted himself a burst of nostalgia after Le Verguier. Clare's wonderful letters, he suddenly exclaimed, ‘never tell me anything about your very own self and I long to hear that you still walk with short skirts and a smiling face about the place in all weathers’. He had been thinking in their rest period ‘of our many happy days spent together’ during their peripatetic wartime life in England and Ireland. There was ‘the jolly time last Easter at Broadstairs … that topping holiday in Brighton … Folkestone that was good fun too though it was only two nights … Clan Rye that was topping and above all Potter's End … that inn in Kent? What was it called? We had some fizz I am glad to remember … finally Thurston Lodge which was perfect.’ One vision of his wife encapsulated this whole catalogue of wartime living from place to place. He dwelt on it in writing about Potter's End, the village where they took a house near Berkhamsted: ‘you looked so topping in our room looking onto the apple blossom’.

Some of their letters related past pleasures to anticipated excitement. ‘I got your letter … yes my love I should love to camp with you again in Devon, somewhere near a river or even the sea,’ wrote Reggie. Their camping holiday near Totnes in 1913 came flooding back. As a married couple it would be different and better next time. Though ‘the privileges of a lover were not inconsiderable were they Pet’, he avowed, recalling chaste but passionate love-making by the River Dart. ‘I shall never forget those happy days,’ he told her. One of his billets, he related in another letter, was in a farm with an orchard, ‘quite like our joy camp at Totnes’. Did she remember that night they had slept out, ‘together in one blanket’, until, to his sorrow, Clare thought it proper to retire about midnight to her tent?

Sex was always present in Reggie's passionate longings, as in his dreams of Clare, at the Front. After finding ‘the waking reality very dull’ once more on 19 September 1917, he urged her to stop worrying in letters about how it would be for them when he came home. ‘I think even if you were very sleepy darling,’ he insisted, ‘I could manage to ring the bell all right … it does not require much effort after this long absence … it would be like having our honeymoon again.’ How he longed for the end of the war, epitomised by a contented family life. He longed for a son and was sad that, four months after his leave, no ‘little Chennie’ was arriving. He reflected that ‘perhaps we will have better luck’ when he next came home.49 Friends had called him Chennie at school.

Clare needed to plan for and set hopes upon their future too. In January 1918 she sent Reggie the Harrods details of a dream house she thought they might possibly afford. But perhaps ‘a farm and fields’ were ‘too expensive a luxury'? Reluctantly, he agreed. Nostalgia became even more necessary to help Reggie through that dark winter, when peace seemed as far off as ever and they were still apart on their third wedding anniversary. Her letters were ‘so delightful’, such a solace, especially the one written on 28 January. He had timed one full of memories of the day to reach her: ‘how clearly I remember it all … my anxiety about arriving on time … how sweet you looked in your wedding dress and “going away” dress … those two dear nights when I had you to myself at last’.50

But writing could also be a deliberate act of dissociation, a kind of going home, during present stress at the Front. Reggie chose to relieve ‘a period of suspense that is not pleasant’, when he had sent a platoon out trench digging, by writing Clare a long letter about the drama of an aeroplane being shot down that day. He paused to see to the rum ration and, sure enough, he declared, returning to his pencil, the men returned ‘within five minutes of the time I estimated’.51

But correspondence had a special privacy and intensity for the soldier which parents, when they were on the receiving end, did not always fully grasp. Wilbert Spencer was very unhappy when his father sent one of his letters to the Daily Mail, chiding him that he found it ‘a bit thick’ to be publicised behind his back. When he subsequently sent photos of himself to his mother, including one in waders to assuage her concern about the mud, he insisted sharply that they must not reach the press.52 Writing letters, it is evident, fulfilled many functions. Those at home wanted news, as did soldiers far from home. Just keeping in touch mattered a great deal. But, at the deepest level of men's emotional survival, there was nothing more crucial than the opportunity letters provided to leave aside the harrowing present. The happiness of the recent past or hopes for fulfilment in a new world yet to come could give men great solace.