‘Sticking it Out’

Fear and Shell Shock

In traditional patriotic thinking war was a test of manhood and character. But the Great War taught lessons which struck at the very heart of Victorian and Edwardian manliness. Neither attendance at a public school nor training in an Officer Training Corps prepared men for the emotional reality of the Western Front. The adventure literature and patriotic verse had swept fear aside. G.A. Henty, Rudyard Kipling and Sir Henry Newbolt did not write about danger in terms which alerted boys to how they would cope when faced with battle. These writers assumed that men schooled in heroic virtues would be able to wave away their vulnerability. Emotional repression together with sheer willpower would be enough to see them through. Service on the Western Front involved a sharp and accelerated exercise in growing up.1

Predictably, by 1918 huge numbers of soldiers had collapsed with shell shock, a condition diagnosed for the first time in 1915. In 1939, 120,000 men were still receiving pensions for psychiatric disability caused in the Great War. Everyone had moments of fear at the Front.2 But at the same time men desperately wanted to hide their fear and prevent their families at home from worrying.3 Remarkably, our letter writers, though chary about being in real danger, almost all provided some kind of account of their first experience of being under fire. They needed solace, and they also believed their families expected to hear about it.

Soldiers at the Front were hardly ever entirely out of danger. One walking in the woods near Poperinge, well behind the lines, in 1915 was killed by a single stray shell which took his head off. When Will Streets found himself, for the first time since he reached the Front, away from the sound of guns in June 1916, he told his mother about the ‘blessed relief’ this gave them all.4 ‘It is lovely to laze on the grass without fear of shells,’ wrote Cyril Newman behind the line at St Amand during the Somme battle. There was renewed sweetness in living when one could see and hear ‘the green grass, the singing of birds, even the hum and buzz of insects’.5

Men mostly narrated their anxieties, times of dread or moments of terror without analysing them. Those who did write reflectively about fear did so within a straitjacket of mental assumptions. Will Streets, so perceptive generally about the strains of war, was elliptical about his feelings after a largely uneventful spell in the trenches in May 1916: ‘of course there are great moments of excitement, of intense animal fear, when the spirit dominates and all that is best in man stands out … we gave them tit-for-tat and blazed away. It gives you greater confidence and spirit when you meet them with a bold front.’6

The padre Donald Hankey wrote pieces in 1915 about the experience of trench warfare which were published in The Spectator. They gained such celebrity that they were published as a book, A Student in Arms, in 1917. One of his essays, ‘The Fear of Death in War’, dealt with the irrational fears men felt when their nerves were tried for hours on end by ‘sitting in a trench under heavy fire from shells’. Hankey described this graphically: ‘you see them slowly wobble down to earth, there to explode with a terrific detonation that sets every nerve in your body a-jangling. You can do nothing. You cannot retaliate in any way. You simply have to sit tight and hope for the best.’ Groping for adequate words, he wrote of ‘an infinitely intensified dislike of suspense and uncertainty, sudden noise and shock’. He called this ‘nameless dread’. It was a wholly physical sensation in his account which could be mastered only by sheer willpower.7

Writing in 1915, Hankey was innocent of psychic explanation of fear in battle. There was not yet any understanding of war trauma. The term ‘shell shock’ had only just been invented. The psychological analysis, under Freudian influence, of fear as memory, which later proliferated in literature, drama and memoirs, lay well ahead. All anxiety and trauma simply had to be put out of the mind or obliterated by strenuous activity.8 Charles Wilson, who became Lord Moran and was Winston Churchill's doctor, much later became an authority in this field.9 He published his observations on the stress of war in The Anatomy of Courage in 1945. His career as a medical officer on the field of battle long before, in 1914–18, was a striking example of integrity and thoughtful investigation. It was not without reason that he dedicated his book ‘To my father who was without fear by his son who is less fortunate’.

Wilson's classic account is both a personal war story and an acute analysis of the psychological effects of war. He knew what difficulties he had borne in containing his own fears. His diary account of the first time he was shelled merely hints at his own terror. When a shell fell on his dugout on 20 December 1914 and the fumes gradually cleared, ‘there was a hole in the wall of the cellar where the shell had come in … I foolishly expected another shell to come in at the same spot, and wanted to move out of the line of this hole, and had a feeling the Boche could see this hole and was watching it for any sign of life.’ It took him time to realise he had work to do, with men injured all round him. Three were lying dead. As he worked he ‘could not help feeling cheerful now that it was over’. But the diary account gave more space to his and his men's emotional responses to the incident than to his work of seeing to the wounded. One day in 1915 Wilson found himself shaking like a leaf under bombardment. He contained this fear and soon after noticed a sergeant alongside him ‘shivering like a reed in the wind’.

His observations of men under stress were a constant theme in Charles Wilson's diary of his time in Bernafay and Trones woods during the Somme. When followed by Germans into a trench, he saw some of his men run ‘like frightened cattle that push and jostle and are harried into the fields through the open gate by barking dogs’. He saw faces ‘which sleep might not have visited for a week’. He watched men ‘who had sat for days under heavy shelling without leaving their trenches, the supreme cold-blooded test of this war’. It was only later that he understood the toll this had taken: ‘even when the war had begun to fade out of men's minds I used to hear all at once without warning the sound of a shell coming. Perhaps it was only the wind in the trees to remind me that war had exacted its tribute.’10

Wilson later developed a highly influential notion of courage which, he argued, was expendable. ‘Courage,’ he wrote,

is will-power, whereof no man has an unlimited stock; and when in war it is used up, he is finished. A man's courage is his capital and he is always spending. The call on the bank may be only the daily drain of the front line … his will is perhaps almost destroyed by intensive shelling, by heavy bombing or by a bloody battle, or it is gradually used up by monotony, by exposure … by physical exhaustion.

A chapter on ‘Moods’ in his book exemplified the extent to which he came to adopt Freudian languages of the self. Churchill refused to write a preface to The Anatomy of Courage because it contained too much ‘damned psychological nonsense’.11

Nothing induced fear like being shelled. This was the primary preoccupation of the new soldier. At the Western Front soldiers quickly learnt how explosive and jagged shell casings, the dreaded shrapnel, tore at men's bodies. Almost three-quarters of the wounds in 1914–18 were caused by shells. They usually went septic because foreign matter entered the body with the splinters. Close bursts of shellfire produced many predictable reactions in frightened men crouching in their trenches: blackouts, numbness, trembling eyelids, shaking hands. Men often had to struggle hard to control their nerves.12

The real barrage, a continuous stream of fire, could send soldiers half mad. In his later memoir Wynn Griffith recalled a youngster's extreme reaction under such a barrage. Following ‘a thunderous crash in our ears, a young boy began to cry for his mother in a thin boyish voice “Mam, Mam …”’ He had not been hit, yet he screamed in terror for his mother ‘with a wail that seemed older than the world’. After some muttering in the platoon, ‘we shook him and cursed him and even threatened to kill him … the shaking brought him back’.13

Predictably, accounts by men from all ranks of their first experience of being shelled have a stark immediacy. ‘It was an awful time,’ wrote Private Horace Bruckshaw in his diary at Vimy Ridge on 3 June 1916. For almost an hour, ‘instead of our superiors leading us out of it they kept us in the centre of it all sheltering as best we could under the ruined walls, all of us expecting every minute to be buried under bricks and mortar at the least’. He saw one man killed and others injured jumping down from ‘the wagon just behind us’.14 Lance Corporal Roland Mountford wrote to his mother after his first sentry duty on 7 November 1915. He came down from the firing step, he explained, and crouched in the trench when shells began to fall thickly about him. He confessed to being ‘in a terrible funk’. Moreover, judging by the faces of others, he believed he was ‘not unique in that’. ‘The row shakes you to pieces,’ he added.15

A week after arriving at the Front, dreaming of the glories of the cavalry charge, Julian Grenfell was explaining to his parents there was simply ‘no job for cavalry’, so the Dragoons had become infantry in the trenches. In November 1914 the full reality of their job came home to him. ‘We've been doing all shelled work lately and it's horrible,’ he told his mother, Lady Ettie, in a week when the German barrage was normally seven hours: ‘you just lie there, hunched up … the noise is appalling and one's head is rocking with it by the end of the day’. After a single day in the front line, Julian accepted, ‘one's nerves are absolutely beaten down’.

Julian yearned for escape, being the kind of man he was, and for action. He pleaded to be allowed to have a go at the bothersome German snipers. Hence his famous stalking raids on 16 and 17 November which won him the DSO. He was as frightened as the next man inactive under shellfire but these stalking expeditions, bagging ‘three Pomeranians’, restored his composure. Is this not the hero you wanted? his account home effectively asked. Julian was happy killing the enemy. It was being under attack that confused him.16

Cyril Newman sent a letter about his ‘baptism of fire’ on 24 May 1915, asking for it to be read to his Sunday school class. This was a consciously constructed exercise in studied bravery for the benefit of youngsters back home. His ‘heart was kept in peace’, he narrated, because he constantly repeated ‘The Eternal God is my refuge.’ He had survived a long night out trench digging in no-man's-land ‘with bullets whizzing round and over us all the three hours’. There was a chlorine gas attack on the way home at dawn which left him coughing and choking. His fear was no more than hinted at in the mild comment ‘I did not like the experience at all’. His interpretation, dramatising the experience for his boys at home, stressed a demonic presence: ‘the Devil was doing with nature as he liked’.

Writing nearly three years later, Cyril had acquired a reflective stance on how he had taught himself to endure front-line shelling. In March 1918, he told Winnie how the ‘ear-splitting and sickening crash’ as a shell burst forced to the surface of his mind ‘reserves of stern endurance and a hardness of heart so that for the time being one becomes Spartan’. By this time, Cyril could give a factual account of his own practice of playing the man: ‘keeping under all sensitive, tender-hearted feelings that, if indulged in, might render one a coward’. It was after each such trial, he admitted, that he craved ‘for a woman's love.’17

When Graham Greenwell suffered an hour's bombardment with the Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire Light Infantry in Ploegsteert Wood on 6 June 1915 he described it as ‘the nearest approach to a battle’ since his regiment had come out. Machine-gun bullets whistled outside the door of the dugout: ‘it seemed as if they must come in though, of course, they couldn't’. Simultaneously the whole wood was being shelled. ‘I found it difficult to smoke my pipe with my usual insouciance,’ Graham admitted, ‘although I was in comparative safety the whole time.’

There were several periods later in 1915 when Graham was worn down by prolonged shelling. Fear for him, as for many, was a cumulative problem over long hours expecting a direct hit. He had a ‘ghastly time’ on front-line duty in October 1915. A letter afterwards contained an especially clear account of why soldiers saw being shelled as a process of ‘wind-up’. The row made by a shell, a ‘low whistle’, was incredible, he explained. Graham reached the state when ‘every puff of the wind startles me and I feel as nervous as a cat’. What finished him was ‘sitting still throughout a solid day listening the whole time to shells and wondering if the next one will be on the dug-out or not’. At the end of a ‘hateful’ day on 31 December, one detects the tension behind Graham's conscientious scribbling of ‘my usual line’ home. He had been back from the trenches for a full hour, yet he was sure shells were ‘still whistling in my ears as they had whistled all day, accompanied by deafening explosions’. They still ‘seemed to be all round me’. Graham was wholly ‘wound up’ and hours must have passed after writing this letter before he recovered his composure.18

Graham Greenwell was far more candid than Billie Nevill. But this was a difference of temperament and personality as much as one of policy on what to tell. Billie had schooled himself to retain the conviction that war was all a game. He managed to maintain his bravado in the front line. Mentioning his first time under fire out trench digging at night on 12 August 1915 almost casually, he turned at once to an excited account of watching star shells and fireballs, ‘awfully pretty, very like an ordinary regatta display’. Boasting a few days later of sitting out ‘in some long grass in “No Man's land”’, he confessed he ‘got about four shots round my tail’ when he bolted back, ‘but the poor souls are too slow’.19

Captain Jimmy Wilson, a Sherwood Forester, explained his feelings when first under fire to his mother in March 1916: ‘I was horribly afraid – sick with fear – not of being hit, but of seeing other people torn in the way that high explosive tears. It is simply hellish. But thank God I didn't show any funk. That's all a man dare ask, I think.’ The next month he wrote to his aunt describing his trench: ‘piled earth with groundsel and great dandelions and chickweed and pimpernels running riot over it’. There was ‘corrugated iron, a smell of boots and stagnant water … and over everything the larks and a blessed bee or two’. Twenty or so shells had come over that morning. His word picture was powerful: ‘you hear a sound rather like a circular saw cutting through thin wood and moving towards you at the same time with terrific speed – straight for your middle it seems until you get used to it’. Then ‘a terrific burst … and sometimes a torn man to be put out of sight or hurried down to the dressing station’.

Painting the same scene in another letter to a teacher in May, Jimmy wrote that the thunder of a shell landing could be just ‘an interesting phenomenon’ to newcomers. To men hardened as he was ‘it is a terrible and fiendish thing’. ‘Mangled bodies are obscene’, he came to feel; ‘war is an obscenity’. Why had schoolboys been taught the romance of war? Jimmy asked. Why had they all grown up soaked in the poetry of war? Their reading masked the personal horror of war. The stories showed ‘nothing of the sick fear that is tearing at the hearts of brave boys who ought to be laughing at home’. In this letter, Jimmy Wilson reflected, ‘it isn't death we fear so much as the long-drawn expectation of it – the sight of other fine fellows ripped horribly out of existence’.20 An important element in the soldier's nameless dread was the tension between the distress of others around him and his own trauma.21

Alec Reader was fortunate in encountering a ‘fairly quiet part of the line’ for his first days of service. He was very miserable after his second tour, confessing ‘I was so nervy I buried my head in the mud and I was not the only one either’. But he put a good face on it to his brother Arthur when asked if he had won a VC yet. Sensible men like him stayed in the bottom of the trench, he replied, ‘when things get a bit hot’. Yet there was a touch of bravado in his claim ‘we all have to do dangerous work. I had to carry boxes of live bombs up to the firing line with shrapnel shrapping all round.’ That was on 8 April 1916. By the 28th, relating a frightening incident to his mother, he was beginning to go to pieces. He had been in a party carrying rations up to the line ‘when shells started bursting about five minutes walk in front of us’. Alec saw no chance of surviving the barrage: ‘it needed all my willpower to keep walking. I felt like dumping my load and running.’ Mercifully, the shelling stopped when they were 300 yards from the trench.22

Peter McGregor was another soldier who first faced shellfire in the early summer of 1916. It occurred as the Argylls marched the last thirteen miles to the line. ‘By Jove to say I had no fear would be a lie,’ he wrote to Jen. ‘I was full of fear.’ He related hearing the whistle of each shell then the ‘sharp nasty crack’ of the explosion. He was on his tummy ‘in double quick time’. Two days later, he tried to write home ‘sitting on the fire step with shells flying overhead’, but he found himself looking at a blank page for a long time. It was too hard to find the words for his pencil against the noise. Back in reserve on 21 June, Peter confessed that his first tour of duty had turned him upside down: ‘no man can experience such things and come out the same’. He struggled to master his nerves. Waking from a night's sleep to a ‘most terrible roar’, he thought himself back in the trenches but ‘it was only a chap banging on a tin tray to wake us for breakfast’.23 The Reverend Maurice Murray made reference to that personal struggle to keep a tight rein, writing to his elder brother during Passchendaele: ‘everyone must funk in a sense … the only thing is not to show it as it is infectious and bad for morale’.24

Some deliberately made light of the strain of being shelled. Quizzed by his wife about coping with gunfire, Reggie Trench confessed that the guns did not worry him at all but the largest German shells were ‘rather trying’. His account was vivid: ‘they come along with a noise like an express train, getting louder every second and ending with a scream and loud bang!’ A pillar of earth was usually thrown up, but, to be consoling, he insisted that the ‘effect was very local’.25 Others by contrast found shellfire almost too difficult to relate. They felt the need to unburden themselves by writing, yet the act of writing and the recalling this required were unsettling.

Wilbert Spencer, much younger than Reggie, described his first involvement in heavy fighting. His letter to his mother displays crossings-out and incoherence. In the first dose of shelling he had seen one of his men killed and four injured. ‘This is the most awful part of war,’ he wrote, hinting at the depth of pain he was feeling.26 Frightening experiences were easier to convey to relatives slightly less close than mothers or wives. During his first days in the front line in heavy rain, Wilbert Spencer gave himself a minor injury through sheer panic, he told his Aunt Vie. Surprised by an enemy rocket on a wiring party ‘in my hurry I jumped down on top of a bayonet which ran about three quarters of an inch into my arm … not serious but quite painful’.27

Everyone felt safer in a dugout than in the open trenches, yet a dugout could become a tomb. ‘We thank God for our dug-outs,’ wrote Graham Greenwell after a bombardment that had lasted an hour at Hébuterne. But he confessed to feeling the same undercurrent of ‘anxiety as to the strength of the lusty beams and boards above us’ as the sailor felt about the stoutness of his ship.28 Billie Nevill at last admitted having been ‘a bit jumpy’ throughout the next day when a shell had landed on his dugout. It exploded, he explained, ‘just the other side of three foot of earth and timber from our heads’. Inspecting the damage in daylight, he found one row of timber and only an inch or two of earth left protecting them.29

Recalling a miraculous escape, Edwin Vaughan remembered seeing where shrapnel had gone through his valise ‘and would have gone through me had I been in bed’. The notion of German destruction of their domestic refuges terrified soldiers. The dugout was a treasured haven. Vaughan carried in his mind, when he wrote up his diary after the war, the biscuit tin, tobacco tin and whisky bottles which were smashed to pieces in that attack.30 Eric Marchant described in a letter a direct hit that buried the knives, spoons, plates and food of some of his fellow officers, besides ‘killing one or two men’.31 All this paraphernalia of daily living symbolised security and a minimal kind of safety.

Those who suffered burial alive, however briefly, were bound to experience trauma. Jack Sweeney had just finished serving his officers dinner on 24 February 1916 when the dugout with its corrugated iron roof caved in under shellfire. ‘My God,’ he told Ivy, ‘I thought my last moment had come.’ He could not answer shouts from the officers because he and another man were buried. It was pitch black. ‘How long I was buried I do not know … at last a party of men came and dug me out, also the other man who I expected to see dead.’32 Coping with a shell that buried men by landing close by was a particular test of resolve. Charlie May and his subaltern Lieutenant Bowby experienced this together in March 1916. A trench mortar threw them to the ground leaving them smothered and badly shaken. ‘I trust the men did not see that my grin was feigned only and that really I was in the deuce of a funk,’ he noted in his diary. Back in his dugout, he found himself shaking. Bowby had ‘brassed it out quite successfully but I knew it had given him a turn’.33

Wiring after dark in no-man's-land, making men vulnerable to machine-gun and sniper fire, was particularly nerve-racking. Will Streets spared his mother the story of his first wiring party in the front line. He told his brother Ben about it with the warning ‘I do not want you to speak of this at home.’ Few men, he said, had experienced this degree of danger so quickly. He had found it valuable to get it over and was proud of his self-mastery. He believed he had earned the respect ‘of one or two senior NCOs’ who before had been loath to give it: ‘I kept my nerves and fear in hand and kept the lead unto the end, even in retiring.’34

When veterans wrote about the war they sometimes recalled and dwelt upon fear. How they had overcome it was integral to their stories of survival. Patrick Campbell went to war at the age of nineteen in April 1917. ‘We were setting out together, knights in shining armour, on the Great Adventure,’ he wrote in a memoir in old age. ‘I had no thought of fear in my head in spite of the unknown that lay ahead.’ It was when the train stopped and he first heard the guns on the horizon that he knew fear. ‘My heart had failed,’ he recalled, ‘my courage had turned to water.’

The next weeks were difficult for him, a green public school boy. But Captain Cecil, ten years his senior, looked after him ‘like an elder brother, warning me how to take care of myself.’ One memory remained especially vivid. It was of a dinner out, ‘the glittering lights of the restaurant, laughter and noise, pretty Belgian waitress’. He had just been under fire. Patrick knew that night that he had won his spurs. Captain Cecil told the others at dinner ‘that I never turned a hair, but was as cool as a cucumber’.35

In November 1914 Dr Charles Myers, a laboratory psychologist from Cambridge, studied cases of mental breakdown in a hospital at Le Touquet.36 He began developing the notion that their nervous collapse was related to shells bursting near them at close range. In March 1915, Myers returned to France, having been appointed consultant neurologist to the War Office. He toured the hospitals along the Channel coast selecting, as he had been directed, cases of ‘nervous shock or neurasthenia’ for transfer to England. Myers was up against the military frame of mind, rapidly finding himself expected to advise courts martial. The Higher Command saw the intervention of psychologists like him as simply making the task of winning the war more difficult. Shell shock was not regarded as a valid defence for cowardice or desertion in the field.

Myers's initial energy was replaced by frustration and anger as he began to understand the human tragedy which lay behind the emergence of the phenomenon of shell shock. The Royal Army Medical Corps was cautious and conservative. Its labels were clear cut: men were either sick, well, wounded or mad. Unwillingness or incapacity to fight made a man a coward. The issue of mental disorder was shrouded in attitudes to honour, self-control and comradeship. Mental illness was equated at the Front with weakness, to be treated by disciplinary methods.

There was more sympathy for sufferers from war neurosis at home. Not that there were any suitable facilities for those who broke down except mental hospitals until four private hospitals were opened in 1915 for short-term rest cures for officers. The medical profession in Britain very gradually came to terms with the real nature of shell shock. In a discussion at the Royal Society of Medicine in January 1916, it was accepted that this covered a series of nervous disorders ranging from concussion to sheer funk. A man's loss of control of his nerves was the single feature these disorders had in common. It began to be noticed that war neurosis took different forms in officers and men. Whereas physical symptoms, such as paralysis, blindness, deafness and mutism, appeared primarily among the men, neurasthenic symptoms such as nightmares, insomnia, depression or disorientation were more common among officers.37 As he developed the theory of shell shock, the psychiatrist W.H.R. Rivers began to see clearly how the differences in education and socialisation of officers and men accounted for this variation in symptoms. The public school officer behaved in ways which showed mental effort to repress traumatic memories. The rank-and-file soldier, less able to control his raw instinct for survival, was closer to a child.38

The medical debate, with its scientific qualifications, was taken up by public opinion and the media in an oversimplified way. During 1915 and 1916 ‘shell shock’ entered the national consciousness. The very vagueness of the term made it a useful, neutral, physical label for a psychological condition that could be accommodated within an ideology of patriotism focused on courage and heroism. The complex reality of the war neurosis being investigated by doctors, meanwhile, passed over the heads of the public. People were thankful to find there was a term they could use for emotional stress and breakdown in combat.39

Shell shock once diagnosed was always seen as an illness by the medical profession and those who made reference to it on the Home Front. Even in the worst conditions only a minority of men broke down psychologically. Shell shock was also viewed as largely curable, though it was accepted that, as with other illnesses, there could be relapse. Its victims no doubt often felt guilty. But British psychologists during the Great War never associated shell shock with dereliction of duty.40

Herbert Trench, our only letter writer to suffer shell shock, broke down early in the war while the national confusion about what exactly the condition was persisted. His story, told in a series of increasingly desperate letters from the Front, is illuminating. It illustrates the process of breakdown in a young man whose bravado had been unwavering. He found it possible to be needy and plaintive to his two sisters Margot and Cesca, though he could not let the mask of bravado slip with others in the family. Above all, his mother had to be placated: in his first postcard on 26 September he asked Cesca to ‘impress on Mother how absolutely safe I am and shall be’. Yet the first family member to receive hints of how he was feeling was, significantly, another young woman of his own generation. Amy Howard was just a little older than Herbert. On a postcard which Clare saw, also dated 26 September, he related that, though not yet near the firing line, he had talked ‘with a Black Watch man, who said amongst other things, that it was more like hell than anything else.’41

Herbert was soon loading Cesca with demands. He started with reading matter, especially poetry; quinine for his cold, zinc ointment, cigarettes and baccy. The first hint of real stress came with the specific request for Marich cigarettes on 14 October when he was near the front line in Belgium. He was asking for these since ‘they are mostly opium’. On 29 October he reminded Margot of the address in the City of London where they could be obtained. It must have been a day or two earlier that Herbert was first under fire. ‘Just come in,’ he wrote in an undated incoherent note, ‘we lay low in soaking rain in the trenches and betted on which of the six the next one would fall on – shell, I mean.’ He requested Oxo cubes and meat ‘tabloids’, adding, ‘I hear there is a chocolate famine in England – if this is so peppermint creams are the next best thing.’42

When he wrote to Margot on the 29th, Herbert summarised his condition after two spells in the front line and ‘some pretty strenuous marching’. He was ‘fairly fit except for the deuce of a cold and general rottenness’. His eight pages expressed gratitude for chocolate and baccy which was ‘absolutely topping’ and for copies of the Irish Times and Punch. He ‘hoped to goodness’ his brother Arthur remained out of it all, posted to Shimla in India. This first full account of front-line duty managed to be poetic as well as graphic. Herbert spoke of the last two miles of the five-mile night march there through the ‘land of snipers’ and the frozen or slushy fields which were ‘damnable to march on’. ‘As soon as it is light you look around and see the German trenches, perhaps eighty or perhaps a hundred yards off.’ At eighty yards, Herbert reckoned, you were ‘safe against shelling and shrapnel’ which would go overhead while at a hundred, he believed, ‘you are more or less safe against a raid’. ‘Anyhow,’ he continued, ‘you stick there, shoot, eat and sleep and swear at the older men as the case may be till you're relieved … then you march back, feeling nearly dead and see the rosy fingered dawn over the purple hills and realise that for that alone, life is worth living.’ ‘Personally,’ he declared with masterly understatement, ‘I do not mind how soon this is over.’

Herbert Trench was coping but he was becoming worn down by insomnia. ‘I want some sulphonal,’ he told Margot on 29 October, instructing her that Burroughs & Wellcome's was ‘the most convenient’, in five gram tablets. Or if that was difficult she should send five gram Veronal. He seems to have known a good deal about barbiturates then available for insomnia. ‘One can't do this sort of thing without sleeping,’ he insisted.43 A few days later he still had the sense of humour to write a postcard to Reggie signed Herbert St Omer, which was a cunning dodge to pass the censor and reveal his whereabouts.44

Herbert's next letter to Margot, on 15 November, made no mention of the insomnia but hinted, in a narrative account of a trench-digging fatigue, how working under shellfire was affecting his nerves. The day before he had paraded at 6.30 after cold bacon and bread, setting out along roads ‘comparable to an Irish bog and no exaggeration with a sixty pound pack’. They started digging, ‘half hour after shells drop over mostly “coalboxes” and a little shrapnel – lie low and go on digging’. More shrapnel meant an hour's wait ‘lying in a soaking ditch till one's frozen’ on the march home. There was no food on return, just ‘cleaning a rifle thick with clay’. The last straw was ‘except for charity of others no baccy’. Nor was there a parcel for him in the mail ‘just in’. This more desperate letter ended with a plea, given four underlinings, for chocolate, baccy and matches. He also asked, via Margot, for cash in five-franc notes from his mother Isabel.45

Writing a postcard to his young cousin Sheelah Trench and to his brother Reggie at Berkhamsted a few days later Herbert managed to compose himself. The bravado was back. ‘We're having a great time out here – a night attack a short time ago and trench digging under intermittent artillery fire – best time I've ever had,’ he told Sheelah. Her father was so impressed he forwarded this to his sister Isabel, Herbert's mother, commenting ‘these young people seem to write in a marvellous cheery strain’. Experience of shellfire was ‘quite entertaining’, Herbert assured Reggie, and their night attack had ‘a sort of “Brocks benefit” Crystal Palace touch’. He was sure the war could not last another year. German casualty figures were reported as enormous. They were said, he had heard, to be entrenching Waterloo for a last stand. The downfall ‘of another Emperor’ there, repeating 1815, would be ‘curious’.46

By late November press reports of the Honourable Artillery Company in action were alarming his mother and sisters living in Dublin. Isabel sent a friend in London to the War Office to ask if Herbert had been wounded. On 28 November Cesca recorded sending off ‘another pound of spare lumps of chocolate … and one and a half pounds gingerbread, soap and matches’.47 When he began his next letter to Cesca on 14 December Herbert was low. He was just back from three days in the front line: ‘water and mud up to one's knees practically all the time – try and realise it’. Nor had the sulphonal arrived. ‘I've got nerves,’ Herbert now confessed. The silver lining was new letters from both sisters assuring him they would not stop writing: ‘the mail is the one thing one lives for out here’.

This letter was continued on the 20th after a spell of better weather in the trenches and a spate of parcels from the family. Herbert had received the sulphonal, marble sugar and Vaseline for his gun. He was suddenly hugely grateful for everything but it was apparent that he was warding off collapse by forced optimism. The battalion had been reduced in less than three months, he reported, from 800-odd to about 450 fighting men. The Allied cavalry would soon see it through, he asserted, keeping the Germans running ‘until the final debacle on the line across Waterloo’. ‘It is very nearly over now,’ he dreamed.48

About ten days after he sent this letter Herbert's incipient shell shock turned to complete collapse. Mercifully for him, this took the form of a physical collapse. He simply fell out on the march back from three days and nights in the front line. He was not at once missed, since he fell into a ditch and lay there unconscious for some hours, till an ambulance travelling the road picked him up. He spent one day at the military hospital on the coast at Wimereux. The casualty form recorded his transfer to England on 2 January with the diagnosis ‘insomnia as nervous debility’.49 Briefly in hospital in Leicester, Herbert discharged himself on the 5th, contacting Reggie. It was he who informed the family in Dublin that Herbert was home. There was panic in the household while it was assumed that he was injured, but a wire soon came from Herbert himself with the message ‘nervous breakdown only trouble, home Sunday’. Ten days of cosseting and an Irish doctor's attentions cleared up the bronchitis contracted from his hours in a French ditch and restored his mental stability.50

On 28 January Herbert attended Reggie's wedding to Clare Howard at Orpington (plate 9). His twenty-eight days’ leave had almost expired. He took advice from his uncle Jack Mackie, whose Berkshire home had become effectively his base in England since his mother's return to live in Dublin the previous summer. His uncle, a magistrate, agreed to sponsor him for a temporary commission in the mechanical transport section of the Army Service Corps. He applied on 2 February, attaching a testimonial of his three-year apprenticeship from the chief engineer of the South Eastern and Chatham Railway. On 18 February his employers until August 1914, the London & North Western Railway, confirmed his satisfactory performance. Herbert claimed experience in driving cars and a steam engine and riding motorcycles. He had owned, he stated, three motorcycles and two cars. The last motorcycle, the Triumph, was the one abandoned smashed in a French ditch in November 1914.51

Herbert, mad on motors, believed he could serve the country best by managing an army transport depot (plate 5). He hoped this would be well behind the lines. After satisfactory interviews, a shell-shock victim who had made a rapid recovery, he was formally recommended for a commission on 28 February 1915. His territorial service expired and he took up his second military career a month later. There was initial training for his work with the Army Service Corps (ASC) at Aldershot from April to June. On 16 July 1915, full of enthusiasm for his new job, Herbert wrote to his mother on board ship. From Boulogne, he explained, he would go to brigade headquarters at Armentières to take up his new duties.52

The Somme brought home to the military authorities in 1916 the magnitude of the threat mental collapse posed to the war effort through severe wastage of manpower. It was at last accepted in the BEF in the autumn of 1916 that shell shock was a genuine disorder with psychological not physical origins. An important policy shift was implemented. This was proposed by Charles Myers and Gordon Holmes, respectively now consulting psychologist and consulting neurologist to the BEF.53 Four receiving centres on the Western Front were set up for diagnosis and initial treatment. Holmes did crucial work on the various states of shell shock, its association with states of exhaustion and the intensity of battle and the rarity of its symptoms in soldiers seriously wounded. Policy on who should be evacuated was refined. During Passchendaele the epidemic of shell shock was arrested. The acute management strategy practised there was temporary respite from battle, along with sleep, food and some comfort, followed by return to active duty. Only 10 per cent of shell-shock patients were now being returned to England. There remained the issue of relapse. Holmes claimed that 10 per cent of casualties relapsed once and 3 per cent twice or more.54

Some regimental medical officers quickly showed a pragmatic understanding of shell shock. Captain Chevasse, in the Liverpool Scottish Regiment, had a sixth sense for noticing men about to collapse. He began having vulnerable men removed from the front line to rest in fatigue companies behind the lines early in 1915. But he could pick out the shirker. Hearing that a Gordon Highlander had shot himself in the leg he poured iodine into it. ‘The shrieks of the poor man,’ we are told, ‘were awful.’55 Resort to self-infliction of wounds was common enough among men feeling close to the edge. There was the favourite old trick of shooting one's finger off when cleaning one's rifle.56 Thomas Marks, in a memoir in old age, recalled seeing men ‘stand on the fire-step and hold both arms above the parapet in the hope of getting hit’. He believed there had been those who ‘got to England with as cushy wounds as they could have desired’.57

Max Plowman was seen by his biographer as ‘a generous and enthusiastic but often tormented spirit’. He commented on variations in the attitude of medical officers to shell shock in A Subaltern on the Somme, a generally careful and unsensational memoir published in 1927, based on letters and diaries.58 Recounting his experience as a young officer at High Wood in August 1916, he found one of his men, a survivor of Gallipoli where he had suffered a fever, ‘lying on the ground breathing heavily and apparently unconscious’. The Medical Officer (MO) pushing him with his foot, declared it was ‘just wind up, the bloody young coward … don't waste my time with these damned scrimshankers’. Plowman and his sergeant kept their eye on the youngster, giving him ‘all the easiest jobs’. Predictably, he had a similar attack after a long march: ‘the battalion now having changed doctors, I send for the new M.O. who orders the boy to hospital’.59

Some doctors suffered a degree of shell shock themselves and were subsequently much more sympathetic to others. James Dunn, MO with the Royal Welch Fusiliers, had seen training and discipline as the invariable answer for men he thought were skulking or ‘trench-shy’. But, finding himself sheltering in a shell hole at Passchendaele, he realised with dismay that his own nerve was failing. The emotional strain of surviving, for more than two years, fresh intakes of all ranks who were subsequently killed or wounded had told on him in the end.60

During 1915, 1916 and 1917 references to shell shock became common in letters and diaries. There was complete moral neutrality and considerable sympathy for the victim in these accounts. Twice in the autumn of 1915, Graham Greenwell told his mother about incidents when ‘the Huns put a shell plum into the trench’. The first time, a sergeant was buried by earth, had to be dug out and had ‘gone a bit off his head’. On the second occasion, the bombardment was prolonged. Graham himself felt ‘most frightfully shaken and pretty rotten but after about half an hour it passed off’. This time ‘a bomber broke down’ seeing men around him killed and wounded. ‘Bucked to death’ with his lads later at Ovillers on the Somme, Graham admitted that one of them had to be removed from the line to the depths of his headquarters dugout when he ‘suddenly went groggy with shell shock’. ‘He can't keep his hands still,’ he narrated sadly, ‘and waggles them the whole time.’61

In May 1915 Rifleman Reginald Prew described how he and his chum George were acting as ‘bomb carriers’ running the gauntlet in the line at Festubert. He noticed someone lying on the ground who ‘every time a gun went off would jump about one foot in the air’. He checked and found it was George, ‘suffering from shell shock, his nerve had evidently failed him running across the open’. Writing home in April 1916, Alec Reader mentioned the ‘rotten experience’ of one of his draft, about twenty-five years old, who ‘lost his nerve and laid in the mud groaning and crying the whole time’.

Innes Meo was a second lieutenant who recorded his own gradual breakdown in a series of tiny diaries on the Somme. ‘I shall probably get the sack as my nerves are no good,’ he wrote on 24 September. He saw the doctor the next day, survived a ‘terrible bombardment’ and by the 30th was in the casualty clearing station. ‘Officer in next bed with awful shell shock, also airman with broken nerves,’ he wrote, ‘God what sights.’ At Messines, Lieutenant A.G. May noted two soldiers going ‘completely goofy’ during an attack. One of them cradled ‘a tin hat as though it were a child’ and was seen smiling and laughing in the midst of falling shells.62

Bert Fereday, who reached the Front aged eighteen in May 1918, confessed to his minister in Wimbledon in August that the horrors of seeing men killed around him, bandaging wounded pals and getting them to safety after a push had left him with incipient shell shock. It was difficult to compose a letter home since ‘I have had such a horrible shaking and have not quite got over it’. ‘If only everyone knew of the horrors of this war it wouldn't last another five minutes,’ he insisted, ‘but until its over we have got to stick it’. Yet he could not conceive facing another day like the one he had just had ‘with the same fortitude or steady nerve’. Had he not been killed the next day he was a predictable shell-shock victim.63

Everyone's understanding of the problem of nerves and of the universal vulnerability to shell shock increased as the war went on. In a long, reflective letter to his brother Phillip after the Battle of Loos, Sir Oliver Lyle explained how he himself had lost his nerve for three days and found himself, during sleepless nights, getting up to check everything each time a shot was fired. ‘Luckily we were relieved soon after and I recovered,’ he explained, ‘but at one time I thought I was going to break down.’ Previously he had scoffed when apparently fit men told him about the problem ‘but I now know that one seems quite fit but feels perfectly bloody’.64

Officers learnt to watch themselves, their fellows in the mess and their men in the trenches for signs of cracking up. Geoffrey Donaldson reported two officers sent back from the line with nerves in July 1916 ‘as it was essential that they should not be near the men while the sort of ague which is the visible and outward sign of the disease was upon them’. The Tommies’ nerves, he argued, depended so much on the strength of mind of those leading them.65 ‘Poor old Gordon has had a breakdown after all his experiences of July 1st,’ reported Lance Spicer from the Somme. He himself was still fit, he said at the start of his letter but he ended it admitting he was ‘not quite up to the mark’ so was being sent to hospital for ‘a rest cure’. Writing a fortnight later from an ‘Officers Rest Station’ twelve miles behind the line, he described his symptoms, suspiciously like incipient breakdown, as ‘sundry aches, headaches, neuralgia etc.’ He enjoyed the quiet and a charming garden to lie about in, declaring ‘all that is wrong is that I am a bit run down and tired’. He recovered and was soon back on duty.66

Robert Hermon had ‘the whole show to run’ when the Northumberland Fusiliers assisted the Canadians in the attack on High Wood on the Somme, because his second in command collapsed the first evening with a nervous breakdown: ‘I had to put him to bed where he was till morning. Poor bloke he wasn't very fit and he was one of two who came through the 1st July and it wasn't to be wondered at.’ Robert believed the strain the Somme was imposing on the BEF should be told directly in England. ‘I saw a man of mine with genuine shellshock,’ he related to Ethel, ‘he was deaf and dumb and though 500 yards away and held by two men he was shaking so you could see his arms going continually.’67

Survivors’ worst memories after the war were often of times when they came very close to breakdown. Charles Carrington was one who sought to deal with such memories with ruthless candour. Twice, in A Subaltern's War in 1929 and in Soldier from the Wars Returning in 1965, he engaged in harrowing self-analysis in relation to the assault which he led with a company of the Royal Warwickshires at Passchendaele in 1917. On his worst day he came close to total and humiliating breakdown. He was under constant shelling in a circular pit five feet in diameter with two other subalterns, one of whom had to steady him when a shell burst close enough to shower them with clods of earth and splinters. But he recovered his nerve. In retrospect, writing forty years later, he described himself as having led his company as a kind of zombie. He was able to observe of himself that he ‘was a quite good company commander and kept up appearances except when, rarely, the live man took charge in a state of high panic’. Yet courage was born from somewhere. Carrington won an MC that day and was promoted Captain.68

It is likely that Herbert Trench confided something of his experience of falling into that French ditch to his older brother. Reggie must have supported his efforts to get back to France. Herbert undoubtedly did well in the ASC with the 21st Siege Battery at first, earning promotion to Lieutenant in March 1916. In a progress report to Cesca in September 1915 he was confident and optimistic: ‘my company is certainly one of the best out here … we've just dug a well, built a rifle range, got our own canteen and I'm now laying a cement floor’. The only grouse was that he had not managed to get a car of his own yet. But he would have one by Christmas ‘if I have to steal it’.

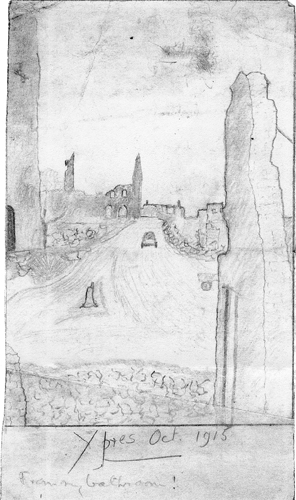

Herbert had won credit the previous week handling the movement of some large guns from England into their positions. His colleagues let the guns get ditched when taking an inadvisable short cut. Herbert went to the rescue. ‘General Currie and the gunners were awfully pleased,’ he told Cesca.69 He sent her a sketch of Ypres, done he said, from his ‘bathroom’, with one of his lorries, ‘not a beetle’ he assured her, moving towards the Cloth Hall.70 He had fought back after his experience in December 1914 and could console himself that he was contributing to the war effort in his responsible transport role.

On leave in early 1916 Herbert enjoyed family visits in London. He was given responsibility on his return for managing a base for the motor transport company of the 15th Corps heavy artillery outside Ypres. For his hut, he built a brick open fireplace with help from his sergeant. Cesca sent him crocus bulbs, which he planted outside. Uncle Benny had promised him a gramophone and ‘some decent records’, he announced on 20 February. There was a hint of future trouble in the comment that the Huns had been dropping some shells uncomfortably close to him, just across the road from his hut by the lorry park. Beyond that, he ended cheerfully, ‘there's nothing doing’.71

In his next letter to Margot in July Herbert described his compound and sent her a plan of it: the park for thirty-three lorries, the canteen, men's huts, the stores, ammunition dump, his hut and private bathroom. There was ‘feverish activity – ammunition stunts for various people’. Rats were bothering him. More seriously, he was finding it essential to play the gramophone to drown the sound of gunfire. There was a strafe going on and he had Tchaikovsky's 1812 Overture at full volume as he wrote.72

It is not clear what exactly caused Herbert's relapse. But in September 1916 he was invalided home. His service papers include notes on a medical examination on 6 September. Herbert confessed that one of his motorcycle accidents had caused a head injury shortly before the war. He also said there had been marriages of first cousins in his family for some generations. He described his nervous breakdown in 1914. The doctor, noting reports of his having recently become ‘very eccentric and nervy with insomnia’, suggested that ‘rest and a change of climate’ might be sufficient for a second recovery. Herbert was treated briefly in a London mental hospital, escaping when he was allowed to the magazines and companionship of the Cavendish Club.

5. Herbert Trench sketch ‘Ypres Oct. 1915 From my bathroom!’

Herbert obtained permission to visit his family in Ireland.73 In October he heard that the War Office's Medical Board had decided he was ‘permanently unfit for general service overseas or at home’. He pleaded that he had been promised two months’ sick leave and was confident he would be fit sooner than that. But, his appeal unavailing, the London Gazette announced on 12 October that Herbert Trench had relinquished his commission ‘through ill health’. He was devastated. Herbert was just one of many such casualties. Yet his recovery on this second occasion was much as he himself predicted. By January 1917, he had obtained work in the Ministry of Munitions in Chiswick and he held down office work of this kind for the duration of the war. ‘Herbert seems to have a job he likes, I hope he sticks to it,’ Reggie commented from the Front in May 1917. Early the next year his indigent state led him to raid Reggie's wardrobe for decent clothes for the office. He could have neither his blue suit, nor his grey one, nor ‘that green tweed one’, Reggie told Clare firmly, but he could take ‘that black coat and any collars and shirts that he wants.’74

It was five months after Herbert Trench left the Western Front that Reggie arrived there with the Sherwood Foresters. He had learnt about shell shock by observing his brother's two truncated episodes of service. When one of his fellow officers soon showed persistent nervous symptoms, his summary to Clare in September 1917 indicates how shell shock for him was simply another kind of illness: Captain Smith was ‘ill again, nerves I'm afraid’. Reggie returned to the subject when writing to his mother in February 1918. His colleague Stebbing, the only other one of twenty-nine officers with the battalion for a full year, was going home for six months as ‘war-worn’. Stebbing seemed all right to him but his well-earned break was a reminder, Reggie reflected, of ‘how some fellows’ nerves go’. He had been speaking the day before near the front line with a subaltern who ‘suddenly started crying’. He was ‘a great big healthy chap’, who had seen much fighting: ‘apparently his nerves have gone suddenly and I think only temporarily so I bundled him out of the trenches and gave him leave to go to Amiens for a day – he'll be alright in a week or two but at present it would be madness to expect him to do his duty’.75

The recognition of shell shock as a serious but often curable medical condition did not involve the repudiation of conventional standards of manliness. As they recovered from shell shock men like Herbert Trench did not lose their patriotic commitment or sense of duty. At one level, shell shock became a political metaphor which was much spoken of yet never received an objective or final definition. At another it was a very real disability that removed men temporarily or permanently from the Front, causing lasting damage to huge numbers of soldiers.76

Once shell shock had become an accepted fact the treatment of men's emotional distress in modern warfare would never be the same again. There was no way that the simple heroic Victorian and Edwardian ideology of manliness could survive intact. It had been established that fear was a basic, a constitutional, perhaps a universal reaction to war. Even the bravest might succumb. Any man's bank account of courage might run out. If, as shown here, fear was often discussed by men writing home in 1914–18, it became an obsessive theme in memoirs and the retrospective accounts of the Great War during the 1920s and 1930s.

One of the reasons for the immense and immediate success of R.C Sherriff's play Journey's End was that his argument was about the emotional costs of dutiful service. Here, in the breakdown through drink of an officer commanding his small dugout, was a hero with a troubled male identity. No Edwardian audience could possibly have tolerated such a stage hero. Yet this was an identity that by 1929 audiences found instantly recognisable. The hallmark of Stanhope's courage in Sherriff's play, instead of an unbending traditional stoicism, was emotional suffering. ‘Sticking it out’, he declared, was ‘the only thing a decent man can do’.77 This was how far the world had travelled during the Great War and after it.