Recipes list

Trofie with Potatoes, Green Beans and Pesto

Pasta Squares with Basil and Walnut Sauce

Triangular Herb Ravioli with Walnut Sauce

Chicken with Olives and Pine Nuts

Spinach with Raisins and Pine Nuts

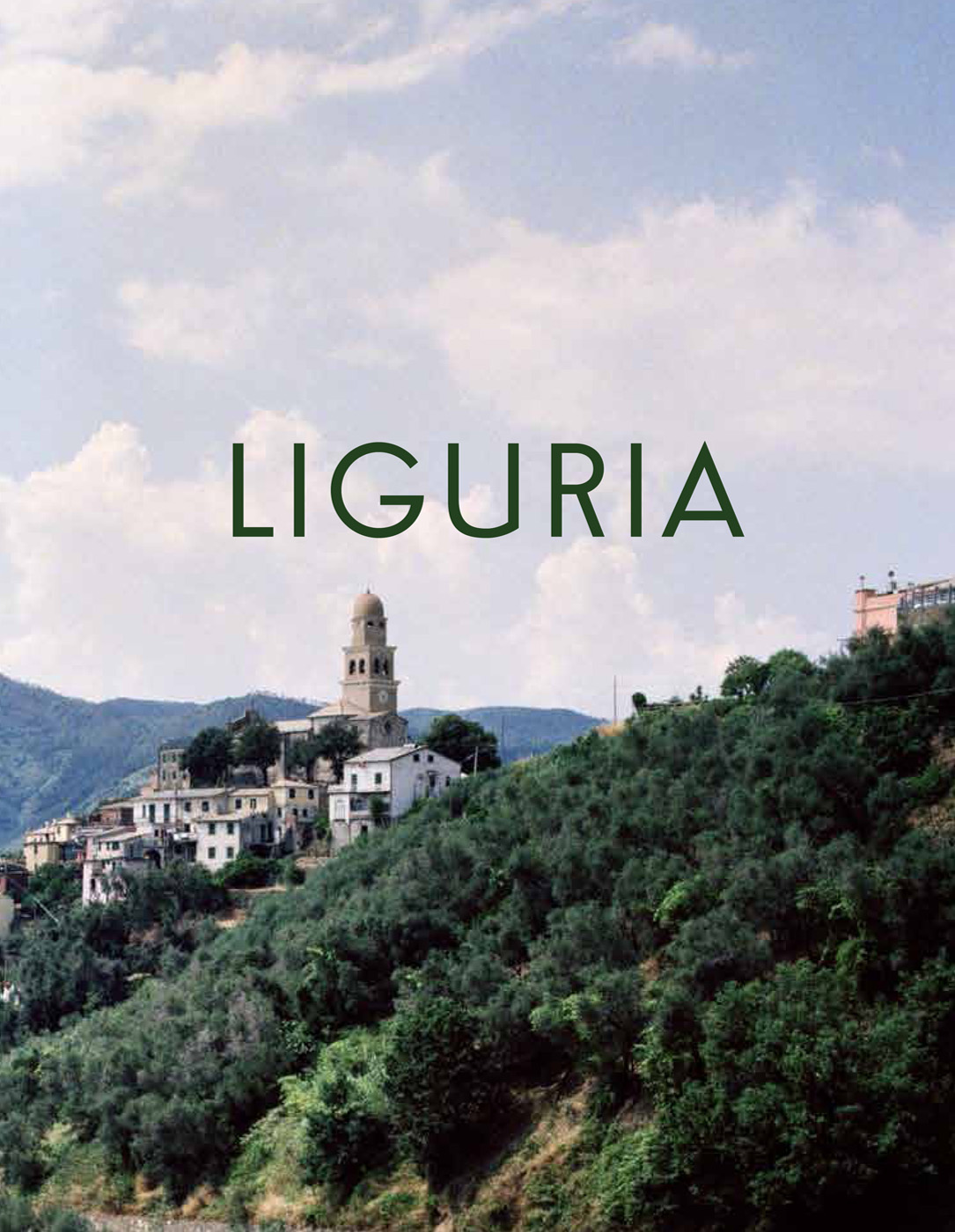

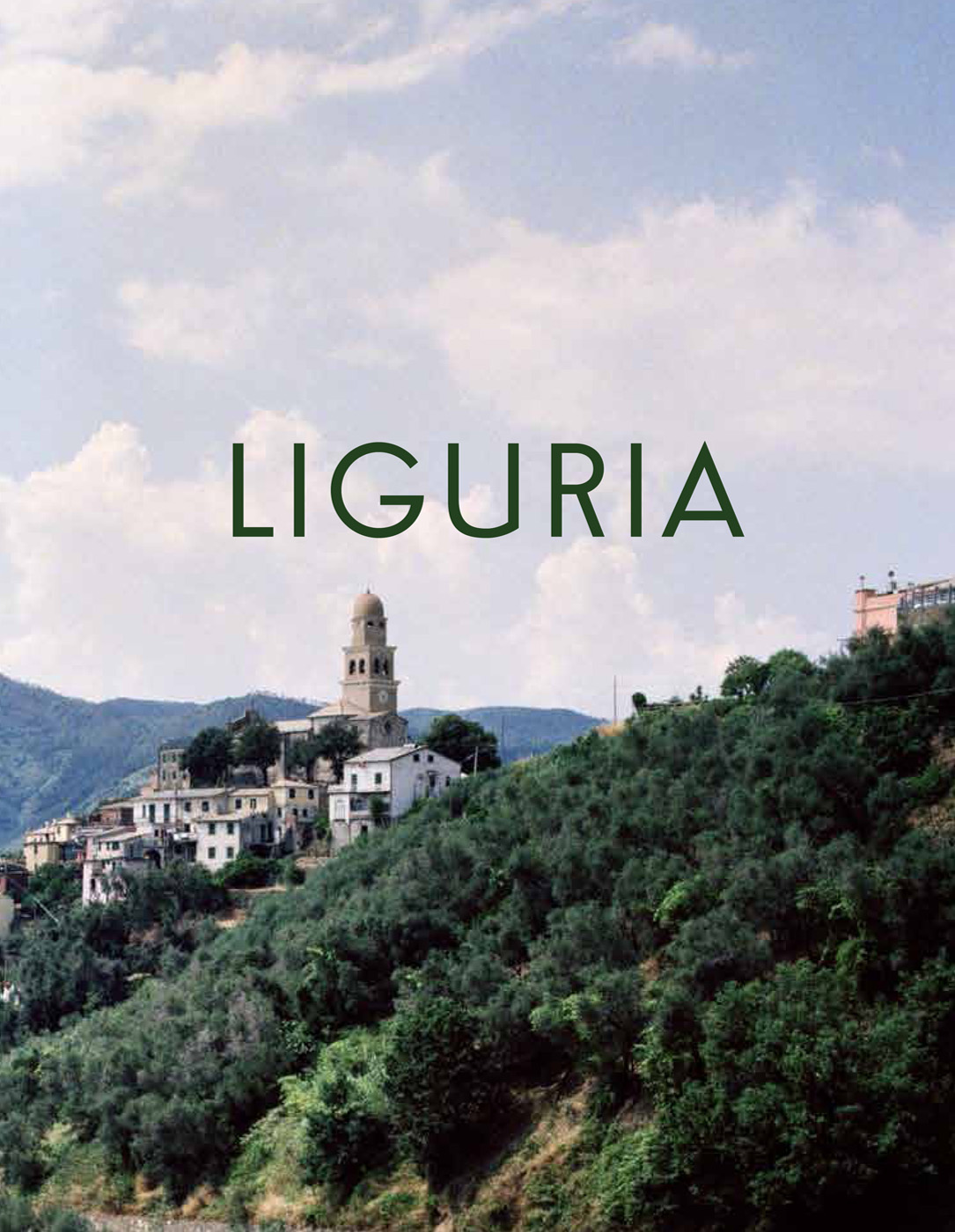

A tiny narrow arc on the sea below Piedmont framing the bay of Genoa, Liguria is all hills that rise up spectacularly from the sea into the high mountains of the Alps and the Apennines. The towns are perched on the coast, and almost a quarter of all Italian tourism is here, attracted by the lovely beaches, the sun and the deep blue sea. Every kind of vegetable is squeezed into the thin strip between the sea and the hills, which are terraced and planted with olives, vines and fruit trees, particularly peaches, apricots, oranges and lemons. The brilliant sun makes everything grow profusely. Colour bursts out from every corner. Bright flowers grow out of crevices and cascade down the walls that support the banks above the roads, and even in the winter mimosa and bougainvillaea bloom. There is intensive commercial cultivation of carnations and other flowers, and the western Ligurian coast is called the Riviera dei Fiori (the Riviera of Flowers).

The hills are covered with wild herbs entangled in the scrub – thyme, sage, rosemary, oregano, marjoram and basil. They perfume the air and characterise the cooking. While Piedmontese food is winter fare, with all its bolliti, fritti misti and brasati (stews), the cooking of Liguria is at its best in the summer months. Both are highly aromatic – the Piedmontese with truffles, wild mushrooms and garlic, the Ligurian with garlic and herbs. Ligurians adore herbs and greenery, and they cook everything with their delicate olive oil, one of the best in Italy.

Ligurian cooking is surprising in many ways. It has none of the characteristics common to the other northern regions, nor is it a cuisine based on the sea, as you would expect from a region with so much coastline. Instead it makes great use of vegetables (as much as Apulia), and its most striking feature is the abundant use of aromatic herbs. The difference from its northern neighbours can be explained by the natural barrier of high mountains which left it isolated in the days when transport was difficult. All Liguria’s traffic and exchanges were made across the sea: it received pine nuts from Pisa, pecorino cheese from Sardinia and salted anchovies in barrels from Spain. The list of special local dishes is extraordinary for such a small region; the cuisine owes more to the land than to the sea because it grew out of the hankerings of her sailors.

For centuries all the men of Liguria were sailors. Christopher Columbus was born in Genoa, which is still Italy’s most active port, and La Spezia is one of Italy’s two naval bases. In the days of sailing when voyages took months, sailors lived on foods that kept forever, such as beans, chickpeas, dry salami and hard biscuits, and, of course, they ate fish. They yearned for fresh vegetables and greenery and fragrance, and during their time ashore this is what their women made to please them. Ligurians adore herbs and make a cult in particular of basil. Everyone grows their own in every available space, in little plots, in window boxes, around the house. Their most famous food – they call it their flag – is the sauce called pesto, which is served with the local pasta: trenette (thin noodles), trofie (made with hard flour and water), lasagne, corzetti (coin-shaped and stamped with a motif) and mandilli di sea, and also with gnocchi and minestrone. To make pesto, bunches of basil leaves are pounded in a mortar with garlic and salt. The basil, like all the herbs that grow in Liguria, is highly perfumed, and when it is crushed it releases such a wonderful scent that it is worth having the patience to pound rather than use the blender, which most use today. Every town along the coast has its own version of pesto. Some make it with pine nuts; some with walnuts; Nervi adds cream at the end; Recco adds a slightly acid ricotta that is like fromage frais. Provence in the south of France makes a similar sauce: pistou. Liguria, which became part of the French Empire in 1806, naturally has much in common with this part of France. They share another speciality: collections of tiny vegetables – courgettes, onions, tomatoes, aubergines and peppers – stuffed with a mixture of breadcrumbs, eggs, garlic, cheese and herbs, including marjoram, and then baked. Ligurian minestrone con pesto, a rich soup with a long list of green vegetables and pesto added in at the end, is very much like a Provençal equivalent. Ligurians, along with the people of Nice and Palermo, use chickpea flour to make a kind of thick pancake which is baked in a huge round tray in a baker’s oven. They call it panissa or farinata di ceci.

Liguria is a truly Mediterranean region: here more than anywhere else you find similarities with southern France, Spain, Greece and the Arab world; as for instance the garlic and bread sauce beaten with oil in a mortar until it is like mayonnaise, and a kind of ratatouille, and fruits preserved in syrup. You even find Arab words. Square lasagne are mandilli di sea (mandil is the Arab word for ‘handkerchief’ and sea means ‘silk’ in dialect). Trenette or linguine are also called by an old Arab name, tria. There were Saracen coves on the Ligurian coast until the tenth century, but the culinary legacy may have come from the trading colonies Genoese merchants established on the coast of North Africa. Ligurian cooking is the cooking of Genoa, and as with all the great Mediterranean ports, many of the influences come from far away.

Another reason the cooking of the sea is not greatly developed here is that this part of the coast is not rich in fish. There are plenty of shellfish – a type of clam called tartufo di mare, sea dates (datteri di mare) and mussels (a hairy type, known as cozze pelose). Ligurians eat shellfish raw, sprinkled with lemon and pepper, or take them out of the shells, dip them in batter and deep-fry them. Shellfish are used with garlic and tomatoes in a sauce for pasta, are cooked in a soup, are stuffed with breadcrumbs garlic and parsley and put under the grill or are simply cooked with oil, garlic, parsley, pepper and wine.

Until 1815, when it was incorporated into the Kingdom of Savoy, Genoa was the capital of the Ligurian republic, which in its heyday had been one of the great financial and commercial powers of the Mediterranean. But Liguria always suffered from the division of the land into myriads of small, constantly warring estates of the local nobility. Some of the history is visible in the medieval city centre of Genoa, where the walls of the tall houses seem too close overhead, leaving only a slit of piercing sunlight to illumine the labyrinth of streets; and in the Romanesque, Gothic and Baroque churches and splendid Renaissance villas, palaces and fortresses that dot the mountains. It is also present in the dishes.

Only two Ligurian wines are widely known and available: the white Cinque Terre and the red Rossese di Dolceacqua. Both are light and fresh but highly alcoholic and go well with the local fish dishes. A fortified dessert wine is Sciacchetra.

SERVES 8 OR MORE

About 950g strong white bread flour

2 teaspoons salt

2 teaspoons fast-action yeast

500ml or more warm water (1 part boiling, 2 parts cold)

150ml olive oil

Coarse sea salt

2 sprigs of rosemary or sage

Put the flour in a bowl, and mix in the salt and yeast. Make a well in the centre, stir in 4 tablespoons of oil and enough water, working it in with your hands, to make a soft dough. Knead for 10–15 minutes until soft and elastic, adding a little flour if it is too sticky. Roll the dough in 1 tablespoon of oil so that a dry crust does not form, cover it with cling film and leave to rise in a warm place for 90 minutes or until it doubles in bulk. Punch it down and knead it again briefly. If you are making 2 focaccias divide it into 2 balls. Spread the dough with your hands onto 1 large (about 45 × 35 cm) or 2 smaller well-oiled trays or baking sheets, stretching it and pressing it, to a thickness of about 1cm. Brush the tops generously with oil and sprinkle with coarse salt and rosemary or sage leaves. Press your fingers in the dough to make indentations all over and let the dough rise again for about 30 minutes. Bake on the top shelf of the oven at 240ºC/220ºC fan/gas 9 for about 20 minutes, or until golden brown. Brush with olive oil and serve warm.

FOCACCIA WITH OLIVES

SERVES 8

1kg strong white bread flour

2 teaspoons salt

2 teaspoons fast-acting yeast

150ml olive oil plus 6 tablespoons to brush on at the end

150ml dry white wine

About 350ml warm water

400g black olives, pitted and coarsely chopped

1 tablespoon dried thyme

2 tablespoons dried oregano

Put the flour in a large bowl and mix in the salt and yeast. Make a well in the centre and stir in 150ml of the olive oil and the wine. Then add warm water, working it in with your hands – just enough so that the dough holds together in a ball. Knead well for 10–15 minutes until smooth, soft and elastic, adding a little flour if the dough is too sticky, then work in two-thirds of the olives and the thyme.

Leave the dough to rise in a bowl covered with cling film for 1–2 hours, or until doubled in bulk, then punch down and work for 1–2 minutes. Divide the dough in 2 and place each piece on an oiled baking tray or sheet. Spread it out with your hands to a thickness of about 1 cm. Sprinkle with oregano and spread the rest of the olives over the top. Make many depressions all over the dough with your fingers. Bake on the top shelf of the oven at 240ºC/220ºC fan/gas 9 for about 25 minutes, or until lightly browned. Brush with the remaining oil and serve warm.

[ pesto ]

Pesto is the prince of Ligurian dishes. The name comes from the word pestare, to crush. Its making is a joyful ritual and the perfume which fills the air is a powerful appetite whetter. There is no place in the world which makes as much use of basil as Genoa, and no place where the plant has as much perfume. Every town has its own version. This is the way they make it at Da ’O Vittorio in Recco. Pesto is served with trenette, tagliatelle, corzetti (coin-shaped pasta, stamped with a motif), with the square mandilli di sea (see here) and the little squiggly-shaped trofie or trofiette and with gnocchi. You can make it all very quickly in the food processor.

SERVES 4

2 cloves garlic, crushed, or more to taste

50g pine nuts

Salt

50g or more basil (weighed with the stems)

4 tablespoons grated pecorino sardo or parmesan

150ml mild tasting extra virgin olive oil

2–3 tablespoons prescinsoa (a creamy acid ricotta) or fromage frais (optional)

Pound the garlic and pine nuts in a large mortar with a little salt. Add the chopped basil leaves (the amount takes into account that basil found elsewhere is less perfumed than in Liguria), a few at a time, pounding and grinding the leaves against the sides of the bowl. Stir in the grated cheese and mix very well, then gradually beat in the olive oil (the olive oil of Liguria is very light, delicate and perfumed) and the prescinsoa or fromage frais, if using.

[ minestrone alla ligure con pesto ]

When sailors arrived from long voyages longing for fresh vegetables and herbs, food stalls in the port of Genoa sold them this soup. Use the vegetables in season. The important part is the aromatic pesto.

SERVES 8

4 medium potatoes, peeled and diced

250g pumpkin or squash, or courgettes, diced

½ cabbage, sliced

75g mushrooms, roughly chopped

125g fresh or frozen peas

150g broad beans, or green beans cut into pieces

400g tinned cannellini beans, drained

5 ripe tomatoes, peeled and chopped, or 1 × 400g tin chopped tomatoes

3 tablespoons finely chopped flat-leaf parsley

Salt and freshly ground black pepper

125g rice or short pasta such as broken tagliatelle

Pesto (here)

Grated parmesan or pecorino

Fill a large saucepan with plenty of water and put in the potatoes, pumpkin, squash or courgettes, cabbage, mushrooms, broad or green beans, peas, and tomatoes. Bring to the boil, add salt and pepper and simmer for 20–30 minutes or until the vegetables are tender, then and the cannellini beans. You can do this in advance.

Before serving, bring to the boil and add the rice or pasta and simmer until al dente. Stir in some pesto, or pass it around along with the grated cheese and let everyone help themselves.

TROFIE WITH POTATOES, GREEN BEANS AND PESTO

[ trofie con patate, fagiolini e pesto ]

Trofie are the spiral shaped pasta, that famously go in this dish so typical of Genoa, but you can use other pasta such as trenette or fettuccine, as in the photo.

SERVES 4

4 small waxy new potatoes, peeled and sliced

150g fine green beans, trimmed and strings removed

Salt

350g trofie or fettuccine

Pesto (see here)

Grated pecorino or parmesan

Put the potatoes and green beans in a large saucepan with plenty of boiling salted water and cook for 10–15 minutes, then throw in the trofie and cook until these are al dente. Drain, reserving a ladle of the cooking water. Mix with the pesto, diluted if you like with a little of the cooking water and serve with grated pecorino or parmesan.

SPINACH OMELETTE

[ frittata di spinaci ]

SERVES 4

1 medium onion, chopped

50g butter

250g fresh baby spinach leaves

5 large eggs

Salt and freshly ground pepper

1 ½ tablespoons olive oil

In a pan large enough to hold the spinach leaves, sauté the onion in the butter over low heat until soft then take it off the heat. Wash the spinach, drain it, and put it in the pan over the onions with only the water that clings to the leaves. Cook, with the lid on, over high heat for a couple of minutes until the leaves wilt in the steam and collapse into a soft mass. (If the leaves have been bought ready-washed and dry, you will need to add about 4–5 tablespoons of water in the pan.)

Beat the eggs lightly in a bowl, mix in the spinach and onions and add salt and pepper.

Heat the oil in a non-stick frying pan over medium heat. Pour in the egg and spinach mixture and cook over very low heat until the bottom has set but the top is still runny. Dry the top very briefly under the grill. Loosen the frittata with a spatula and lift it onto a serving plate. It is good hot or cold.

PASTA SQUARES WITH BASIL AND WALNUT SAUCE

[ mandilli al basilico e nocci ]

For the very fine square pasta called mandilli di sea in Genoese dialect (mandilli comes from the Arabic for handkerchief, and sea means silk) make fresh egg pasta (see here) and roll it as thinly as you can then cut it into 10cm squares. Or use bought fresh lasagne and cut them in half or dry ones as they are. (This pasta is now sold all over Italy ready-made in packets so perhaps we will be able to buy it here soon.) Serve it with the sauce below or with the pesto on here.

SERVES 2

40g grated pecorino or parmesan

Large bunch of basil (about 20g)

25g walnuts

1 garlic clove, crushed (optional)

6 tablespoons extra virgin olive oil

150g fresh or dried lasagne

Salt

Blend the cheese, basil and walnuts, and the garlic, if using, together in a food processor then add enough oil to have a creamy sauce.

Drop your pasta or bought lasagne gently, one piece at a time, in a large pan of vigorously boiling salted water, and cook stirring often so as not to let them stick together (it does not matter if they tear), until al dente. Scoop up a ladleful of the cooking water and drain.

Serve at once directly on plates with the cold sauce – diluted if you like with a tablespoon or so of the cooking water – poured over.

TRIANGULAR HERB RAVIOLI WITH WALNUT SAUCE

[ pansoti con salsa di noci ]

Pansoti means ‘pot-bellied ones’. Different kinds of wild Ligurian herbs and leaves (preboggion is the general term) may go into the filling. These are with spinach and watercress. Serve them with the walnut sauce in the recipe that follows.

SERVES 10

For the filling

1kg beet greens, Swiss chard or spinach and borage, or 500g frozen spinach

2 bunches watercress (175–200g weighed with stems)

Salt

200g ricotta

50g freshly grated parmesan

25g unsalted butter, melted

2 eggs

Pepper

¼ teaspoon nutmeg

For the dough

400g flour

Salt

1 large egg

2 large egg yolks

120ml water

For the filling, wash all the fresh green leaves, remove the stems and cook in very little salted water, turning them over with a wooden spoon until they crumple to a soft mass. Drain and squeeze every drop of water out, then chop finely (in a food processor if you like) and mix well with the rest of the filling ingredients. Frozen spinach need only be defrosted and squeezed dry before mixing with the other ingredients.

For the dough, mix the flour and a pinch of salt with the whole egg and 1 yolk; add only enough water so that the dough holds together in a ball, working it in with your hands. Knead for 10–15 minutes, or until the dough is smooth and elastic, adding a little more flour if it is too sticky. Wrap in cling film and leave to rest for 30 minutes, then roll out as thin as you can on a lightly floured surface with a floured rolling pin. Cut the sheet into 5cm squares and brush the edges with the remaining egg yolk. Put a heaped teaspoon of filling in the centre of each square and fold it over into a triangle, pressing the edges firmly to stick them together. (You can bring the ends together to make the traditional headscarf shape but it is not worth doing if you risk tearing the dough.)

Cook the pansoti in plenty of salted boiling water for 3–5 minutes until al dente, then drain and serve covered with the following walnut sauce.

[ salsa di noci ]

Use this sauce for the previous recipe or with bought spinach ravioli.

SERVES 10

300g shelled walnuts

1 clove garlic, crushed

2 slices country bread, crusts removed

300ml whole milk

50g freshly grated parmesan

5–6 tablespoons mild tasting extra virgin olive oil

Salt and freshly ground black pepper

Blend the walnuts and garlic, the bread soaked in the milk, the cheese and olive oil (the Ligurian oil is mild and delicate) to a cream, adding salt and pepper.

RICE AND SPINACH CAKE

[ torta di riso e spinaci ]

SERVES 8

500g fresh young spinach

250g risotto rice

Salt

1 onion, chopped

1 tablespoon olive oil

25g unsalted butter

3 large eggs

4 tablespoons grated parmesan

Freshly grated black pepper

A good pinch of nutmeg

Wash the spinach and remove the stems. Cook until it softens (frozen spinach needs only to be defrosted), then drain and chop finely. Boil the rice in salted water for about 10 minutes until nearly done, throw the spinach in with the rice, stir well and drain at once.

Fry the onion in oil until golden and put it in a bowl with the rice and spinach. Add the butter, eggs and cheese, pepper and nutmeg. Mix well and press into a buttered non-stick mould or cake tin. Bake in the oven at 200ºC/180ºC fan/gas 6 for about 25 minutes, or until golden.

Turn out and serve hot. It is also good cold.

VARIATION: For preboggion con riso, add a bunch of chopped herbs, such as mint, basil, marjoram, oregano, thyme, sage, rosemary or parsley, and 1–2 crushed cloves of garlic with the spinach.

CHICKEN WITH OLIVES AND PINE NUTS

[ pollo pini e olivi ]

Ligurian olive oil, olives and pine nuts are famous for their delicate flavours. Here herbs, garlic and white wine complete the taste of the region. Use good-tasting olives.

SERVES 4

3 tablespoons extra virgin olive oil

6–8 chicken thighs

4 whole garlic cloves

200ml dry white wine

1 teaspoon sugar

Salt and freshly ground black pepper

1 sprig rosemary

1 sprig marjoram

250g plum tomatoes, peeled and cut into pieces

80g green olives

25g pine nuts, lightly toasted

Heat the oil in a large frying pan and put in the chicken thighs, then cook over medium high heat, turning to brown them lightly all over.

Add the garlic and when it begins to colour, add the herbs and pour in the wine. Lower the heat, add sugar, salt and pepper, and simmer, covered over low heat for about 15 minutes. Turn the chicken pieces over, put in the tomatoes, olives and pine nuts and continue to cook, covered, for another 10–15 minutes or until the chicken is very tender.

SPINACH WITH RAISINS AND PINE NUTS

[ spinaci all’uvetta passolina e ai pinoli ]

SERVES 4–6

1kg spinach

4 ripe tomatoes, peeled and chopped

1 tablespoon extra virgin olive oil

2 tablespoons unsalted butter

2 tablespoons raisins, soaked in water for ½ hour, then drained

Salt and freshly ground black pepper

Pinch of nutmeg

2 tablespoons pine nuts, lightly toasted

Wash the spinach and remove any hard stems. Drain and squeeze the water out. In a very large saucepan, heat the tomatoes in oil or a mixture of butter and oil until soft. Put in the spinach and the drained raisins and put the lid on. Cook for 2–3 minutes until the leaves crumple. Season with salt, pepper and nutmeg, stir in the toasted pine nuts and serve hot.

[ triglie alla ligure ]

This is how Gianni Bisso cooks red mullet at Da O’Vittorio in Recco.

SERVES 2

2 × 250g red mullets, cleaned and scaled

4 tablespoons extra virgin olive oil

150ml dry white wine

Pinch of salt

50g black olives, pitted

2 cloves garlic, chopped

1 lemon, cut in half

2 tablespoons chopped flat-leaf parsley

Put the fish in a baking dish with the oil, wine, salt, olives, garlic and lemon halves. Cover with foil and bake in the oven at 180ºC/160ºC fan/gas 4 for 20 minutes, or until the flesh flakes easily when tested with the point of a knife. Serve sprinkled with parsley.

QUINCES IN SYRUP

[ cotogne in composta ]

This preserve keeps well and makes a ready dessert to serve with a blob of mascarpone.

SERVES 6

1kg quinces

250g sugar

Thinly pared peel of ½ lemon

Juice of ½ lemon

1½ teaspoons cinnamon

6 cloves

150ml dry white wine

Wash and scrub the quinces and cut them in half. They are extremely hard so you will need a big strong knife. Do not peel them, just trim the ends, and leave the cores and seeds that lend a jellied quality to the syrup. Put them in a large saucepan with the rest of the ingredients and enough water to cover.

Simmer for about 1 hour, until the fruit is tender, then lift out the quinces. Cut them into slices, remove the cores and seeds and arrange them in a serving bowl. Reduce the syrup a little and strain it over them. Serve cold.