The commercial and political success of Maya city-states was dependent on their ability to efficiently maintain the flow of communication, commercial trade, and the movement of traffic between city-states. Their ability to travel between strategic destinations was dependent on the condition of overland routes. These routes, once limited to winding jungle trails, left travel conditions at the mercy of the capricious natural environment.

The vast majority of the 125,000-square-mile Maya realm consisted of rough natural terrain, overshadowed by the dark rainforest canopy, overgrown with tangled roots and covered with slick, green moss, making travel difficult in any weather condition. During the long rainy season, copious amounts of tropical rainfall made travel on the rutted soil tracks difficult for the typical traveler and nearly impossible for the cargo porters straining under back-breaking loads.

Maya technology was challenged to develop a creative solution that would overcome the reliance on rough jungle trails. These routes retarded travel in the best of weather conditions and became a quagmire of torturous proportions during the rainy season. Maya creativity rose to the challenge of travel routes that restrained commerce and hindered the power base of the city-states. The solution was an all-weather road system that facilitated the flow of goods, communications, and the swift movement of military traffic, while enhancing political and economic relations between polities.

This innovative roadway system was developed around 300 BC and spread throughout the realm. Maya call these roads sacbe (plural, sacbeob), which means “white road,” referring to the white color of the road pavement. The road systems were constructed well into the late Classic Period and used for centuries in the Post-Classic Period with little maintenance. Examples of these roads have been observed throughout the Maya world, and they represent a significant investment in capital resources and human labor. Their construction and application were an important element in the Maya system of politics and commerce.

The Maya power elite, when faced with a transportation dilemma threatening the growth of their wealthy and powerful city-states, began the search for a technological solution. The transportation of commercial goods, military movements, communication, and other travel purposes could not operate on the treacherous jungle trails. The requirements set down by elite management became the engineering criteria for an efficient ground transportation system that would be adopted throughout the Maya world.

Maya engineers approached the challenge by focusing their creativity on the use of proven technical innovations to develop solutions for an all-weather highway. Their solution was one that would support a variety of two-way traffic and was constructible in a variety of environmental conditions, including jungle terrain, savannahs, and marshlands, using locally available materials. To develop the optimal design for a multi-functional, all-weather roadway, Maya engineers applied their proven technology, materials of construction, and engineering skills to develop the innovative prototype. They combined design and construction materials, including structural engineering, linear surveying, cast-in-place concrete, composite masonry and concrete systems, and construction management.

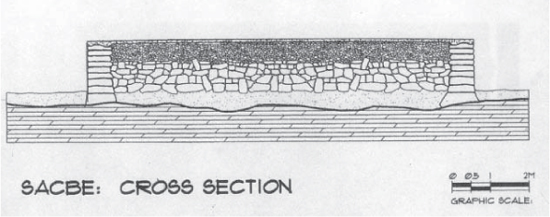

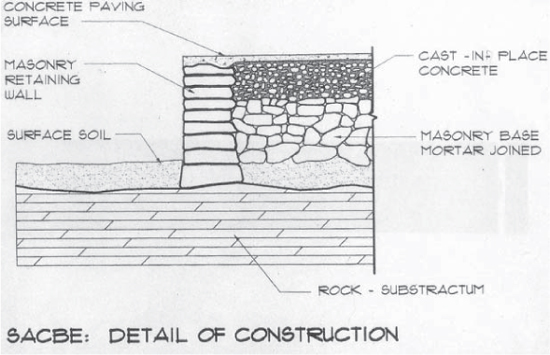

The design methodology for implementation of the engineered routes included a variable criterion that enabled construction of the roads in diverse terrains. The specifications allowed the use of local materials available along the route. The basic geometric profile of the sacbe required a 10-meter-wide, paved, concrete surface elevated a minimum of 1 meter above the ground surface by stone sidewalls and a cast-in-place concrete base. The smooth, white, concrete pavement of the road enabled a solid non-slip footing for travelers while resisting the growth of invasive jungle vegetation. To maintain a dry pavement, the surface of the concrete paving was shaped with a convex crown to facilitate the drainage of storm water from the road surface. The sidewalls elevated the roadway above the jungle floor to prevent flooding during the rainy season and deterred jungle growth. Maya engineers relied on the elevated surface of their roads to keep their pavement clear of mud, storm water, and the attack of the encroaching jungle. The geometry, construction details, and composition of the typical sacbe is shown in Figure 9-1 and Figure 9-2.

The construction of a sacbe began with the selection of the route and the engineering design of the roadway. Maya roads were designed as straight alignments between two points, no matter what the distance. The alignment followed the vertical geometry of the surface terrain, rather than using cut-and-fills to change the vertical contours of the roadway. Maya engineers preferred road routes to pass over the crest of a hill or follow the contours of a natural depression. This method of alignment also reduced the opportunity for ambush by invaders by eliminating potential hiding positions.

The field engineering for the construction of a Maya roadway used a few simple surveying instruments. The basic engineering tools have not changed in contemporary road construction. The basic tools for establishing horizontal lines and right angles were based on the plumb bob, string lines, and water levels. Curved roads were just not in the Maya repertoire. The basic surveying tool used by the Maya was based on gravity, whereas contemporary surveying instruments are based on digital technology that use laser beams for leveling and distance. The results are the same, but digital tools are 99 percent accurate. The overall alignment of Maya roads was based on celestial navigation.

The route of the sacbe cut an open swath through the forest, enabling sunlight to penetrate the shadows and dry the surface of the roadway after a rain. The same open slot permitted the surface of the white roads to be illuminated by moonlight and starlight. This celestial light enabled travel during the night, making the sacbe a true year-round transit route.

Figure 9-1: Cross section of structural detail and geometry of typical sacbe. Author’s image.

Figure 9-2: Detail of Maya sacbe with materials of construction shown. Author’s image.

The 10-meter-wide sacbe had sufficient width to offer the opportunity for two lanes of travel in each direction. Lacking the advantages of beasts of burden, the Maya relied on manpower for transportation. It is apparent that heavily laden bearers would keep to the outside or “slow lane” in each direction. Fast movers, such as messengers, travelers without burdens, and military traffic, would have the right of way in the inside fast lanes. These four lanes of traffic would require the entire 10-meter-wide pavement, with 2.5 meters for each of the four lanes. Modern roads have lanes that are 3 meters wide for highway traffic, a very similar lane width to that used by the Maya.

The sacbe system, in many cases, extended for long distances. To provide aid and support for travelers, the sacbe system included rest stations with water and provisions. Military garrisons were positioned along the routes to maintain order and carry out administrative duties, such as the collection of tolls. The sacbe system extended throughout the peninsula, interconnecting the major city-states. The concept, purpose, and geographic distribution of the sacbe system was similar to the interstate highway system in the United States, the Autobahn system in Germany, and the Roman road system in the Roman Empire. It served to enable military forces to move swiftly to a trouble spot. The hard surface of the sacbe provided a firm footing for marching warriors. The paved roadways also became a major economic factor and grew the wealth and culture of the Maya. In a similar manner, the modern interstate highway and the Autobahn have changed the primary purposes of the highways from a military role to the lifeline for economic transport.

Historically, Roman road construction has been considered the ultimate in well-constructed, all-weather roads. These roads outlasted the sturdy building constructions of the Roman Empire for a millennium and a half. The Roman roads were well constructed all throughout the empire, but were at their optimum in Italy, where cast-in-place concrete was available to the road builder. However, the Roman roads north of the Rubicon River were also well constructed of locally available material.

The comparisons of these famous Roman roads with the Maya sacbe system indicate similarly sound structures that have also lasted for well over 1,000 years. In addition, the construction techniques used by both technologies are quite similar. The major difference is the elevated geometry of the Maya road surface. The Romans based their design on the natural environment of Europe and North Africa versus the tropical jungles and rainstorms in the Maya criteria. Maya roads were elevated a meter above the adjacent terrain, whereas Roman roads were built just above grade level. Roman roads were 6 meters in width, and the Maya roads were 10 meters in width. Like Maya engineers, the Roman civil engineers constructed their roads to follow the natural terrain. The quality of the construction of the roads depended on the strategic importance of the road and the availability of local materials. Major, fully paved Roman roads were constructed of four to five layers of structural-grade materials installed in a foundation excavation of approximately 1 meter in depth.

The depth of the foundation depended on the quality of the supporting soil. Roman engineers used innovation in order to select appropriate local materials for road construction. Construction initiated with the survey of the road’s centerline, using survey tools similar to the Maya, based on the plumb bob and the water level. The foundation excavation down to bearing soil proceeded along the centerline. The strata of construction materials included a base course of sand and mortar, followed by a layer of flat, worked stones that were set in mortar, and then a layer of gravel set in clay or concrete. The final structural layer was the installation of large, worked, hard stones set in concrete. The top level of hard rock was the travel surface; this stone pavement was laid to produce a crown for drainage. Large curb stones were set at the perimeter, and the lateral drainage gutters completed the construction.

The Roman engineers and their contemporary Maya counterparts followed the theory that a well-constructed road would require minimum maintenance. The Maya road-builders had the luxury of an ample supply of cement for producing cast-in-place concrete, concrete paving, and stucco. Roman road-builders were required to rely on a source of natural volcanic cement found only in Italy. Transport of this valuable construction material had a limited range. It has been only in recent years that road-builders have returned to quality road construction similar to the Maya and Roman roads.

Many Maya roads have been covered by the encroaching jungle and alluvial material, and have been degraded by the roots and lack of maintenance. However, some Maya roads have been paved over and serve as the base for contemporary highways. Thousands of miles of sacbeob stretched across the Yucatán Peninsula during the Classic Period. By comparison, only 114 miles of paved road had been built in the United States before 1914.

When the conquistadors invaded the Yucatán in 1542, the Maya sacbeob had fallen into a state of dilapidation, due to the 600 years that had passed since the decline of the Classic Maya civilization. Maintenance and construction of the roads had ceased and the jungle environment engulfed the marvelous road systems. Although some roads were reported to be in a state of usable quality, the majority of the sacbeob were in a state of deterioration, covered by jungle tendrils and alluvial deposits.

The first reports of the Maya roads were recorded in the 16th century by colonial historians; later accounts of observations in the 19th and 20th centuries were noted by explorers, archaeologists, and travel writers. Archaeologists did not carry out formal studies of the sacbe system until 1934, when the Cobá to Yaxuná sacbe was surveyed by the Carnegie Institution of Washington. After Alfonso Villa’s report, “The Yaxuná–Cobá Causeway,” on the 1934 survey was published in Contributions to American Archaeology, many archaeologists doubted the actual existence of the Maya roadway system. Archaeologists, when judging the existence of the roadway system, considered the raised highways to be unique to the eastern Yucatán. However, research of historical chronicles, journals, and reports by observers indicated that sightings of the sacbeob have been reported for centuries at various locations across the breadth of the Maya domain.

Maya strongholds in the southern lowlands and the Petén were not conquered by the Spanish until the dawn of the 18th century, some 150 years later. Reports of sacbe sightings from that area of the Maya world came later in history. After the conquest and during the colonial period, the 300 years of Spanish rule discouraged exploration of the Yucatán, which only began in earnest after the Mexican Revolution in 1821, when travelers and archaeologists began to explore the technological and artistic works of the Maya. Written accounts of the reports by historians and soldiers, though mostly a footnote to history, indicated that a technologically advanced highway system had been observed throughout the domain of the Maya city-states and were not solely confined to the eastern Yucatán.

The reports of an advanced roadway system constructed by the ancient Maya were considered by archaeologists to be a mythological feat remembered as a folk memory by the native culture. The reports of these roads were solely based on Spanish historical chronicles recorded by conquistadors until the mid-19th century. Moreover, actual Maya roadways had not been identified and studied until the 20th century. Archaeologists did not investigate the fabled roadways until the 1934 Carnegie survey of the Cobá to Yaxuná sacbe.

Although the majority of early reports of Maya roads were from the Northern Yucatán, exploration, archaeological investigation, eyewitness observations, and Spanish colonial accounts have described encounters with the ancient roads in diverse locations throughout the realm of the Maya. It has become apparent that the standard design of the engineered roadway was adopted and constructed through the Maya world. The sacbe system was a common denominator for transportation and communication adapted to suit local political and environmental conditions.

Research has indicated that parts of the sacbe system were in use by 300 BC and were still in use well after the collapse. Early records of observations of the Maya roadway system were recorded in 1562 when Bishop Diego de Landa, in Relación de las cosas de Yucatán, reporting on the architecture of the city of T’hó (Mérida), wrote, “There are signs nowadays of there having been a very beautiful causeway from some to others.” De Landa also described a 62 km paved road extending from T’hó to Izamal. In 1610, Bernardo de Lizana made reference to ancient roadways in his Devocionario de Nuestra Señora de Izamal y Conquista Espiritual de Yucatán (Prayer Book of Our Lady of Izamal and Spiritual Conquest of the Yucatán). When describing the Maya religious center of Izamal, he wrote, “They...made pilgrimages from all parts, for which they had made four roads or causeways to the four cardinal points, which reached to the ends of the land and passed to Tabasco, Guatemala, and Chiapas...so that today in many parts may be seen pieces and vestiges of them.” In 1688, Diego Lopez de Cogolludo observed there were paved highways that traverse and ended on the east on the seashore so that pilgrims might arrive in Cozumel for the fulfillment of their vows.

It would be 233 years before another historical note relative to observations of sacbeob was recorded. John Lloyd Stephens describes reports of the sacbe from Cobá to Yaxuná. He describes the architecture of Cobá with a calzada or paved road, of 10 or 12 yards in width, running to the southeast to a limit that has not been discovered with certainty, though some agree that it goes in the direction of Chichen Itza.

In 1883, Désiré Charnay, the French archaeologist and explorer, reported that on his explorations he encountered an ancient paved roadway in the eastern Yucatán from Izamal to the sea, facing the island of Cozumel. Charney was reporting on a portion of the sacbe that extended from T’hó to the Caribbean coast at the town of Ppole (Puerto Morelos). Reports of sections of this fabled sacbe have been reported by de Landa and Diego Lopez de Cogolludo. This route has been referenced in Colonial and modern studies, and would have extended in an east–west direction from Mérida to Puerto Morelos.

It would be the 20th century before Victor Pinto verified the nature and route of the 20-kilometer sacbe from Kabah to Labná in the Yucatán. In 1912, Dr. Sylvanus Morley reported that when construction crews from the United Fruit Company were constructing a company railroad in Honduras, the excavations carried out on the outskirts of Quiriguá encountered a “magnificent causeway of cut stone.” It was reported that the sacbe extended from Quiriguá to the northeast traversing toward an unknown destination.

In 1966, Lawrence Roy and Dr. Edward Shook investigated the sacbe extending from Izamal to Aké. They walked the route, taking compass readings and measuring its width. This east–west route may be part of the fabled 300-kilometer Ppole to T’hó road. In 1959, geologist A.E. Weidie reported that a railroad formerly used by chicleros extended to a point 20 km west of Puerto Morelos, and that the railroad had been built on the raised structure of an ancient roadway extending in an east–west direction. From 1995 to 2002, archaeologist Jennifer Mathews of Foundation for the Advancement of Mesoamerican Studies, Inc. (FAMSI) carried out surveys on that same sacbe. Her studies extended 48 kilometers to the west from Highway 360 at Puerto Morelos. Her reports detail surveys and photographs of a broad sacbe with a prototypical design configuration. The numerous inter-site sacbeob at the ancient city of Cobá, surveyed and recorded by Dr. William Folan and Dr. George Stuart in the early 1970s, indicate the role of the roadway system in a city’s development. Dr. William Folan also investigated sacbeob extending from Calakmul to El Mirador. The sacbeob were observed crossing marshland as they extend toward El Mirador. These sacbeob, a modified prototypical design using earth fill to suit the marshland conditions, were studied by Folan in the 1990s. Archaeologist Richard Hanson, in conjunction with NASA, is investigating sacbeob extending from El Mirador to other sites. Archaeologists Arlen and Diane Chase have surveyed sacbeob extending from the site of El Caracol in Belize. The historical and contemporary reports of engineered roadways by the ancient Maya have presented sufficient evidence that indicates not only their very existence, but their wide distribution throughout the Maya domain. David Bollen, in a paper submitted to FAMSI, stated that a few years ago it was thought that sacbeob did not exist in Campeche, the Petén of Guatemala, or in Belize. Now that there is valid reporting of the wide range of sacbeob, it would seem that the discoveries of them crossing the great Maya domain have just begun.

Archaeo-Engineering Surveys of the Sacbeob

The traces of sacbeob were often difficult to visually locate due to shrouding by the rainforest environment. In some cases, the ancient roads were covered by jungle detritus and alluvial fill, and degraded by prying roots. Man has also contributed to the destruction of the ancient roads. They were dismantled by local builders who used the stonework of the road structure as a quarry. They have been destroyed by modern developmental activities and agricultural expansion. However, the low vertical profile of these roads is another reason for the difficulty in locating evidence of their presence. The sacbe, which is barely a meter in height, does not present a noticeable mound or high vertical profile. The majority of encounters have been by chance and are usually the product of other archaeological or construction activities. Aerial photography and remote sensing by satellite have increased the incidents of detection of the linear telltale traces of these roadways. These roads can be also viewed by an observer on the Internet. Vestiges of the roads can be visually located on Google Earth, which has become a valuable tool for archaeological research, and for viewing sacbeob and other artifacts. The length and remoteness of these roads have not attracted the archaeological investigations that have been lavished on the Classic cities. The cost of searching for and consolidation of the roads on the ground would be prohibitive.

The 100-kilometer sacbe extending from Cobá to Yaxuná exhibits the classic criteria of the Maya road system. This route is the only long-range sacbe system that has been surveyed by an archaeological institution. The original survey, carried out in 1934 by Alfonso Villa, ascertained the route of the road and encountered unique archaeological artifacts along the route. The published report included a map, photographs, and a detailed narrative of the survey and historical background on sacbeob.

From 1995 to 2002, a comprehensive, digitally based ground and aerial survey of the Yaxuná to Cobá sacbe was carried out by an archaeo-engineering team led by me. A survey had not been carried out on this route since Villa’s work in 1934. Extensive archaeological surveys of sacbeob were carried out in the 1970s in the area of Cobá, a sacbe-rich site. However, the surveys did not include the route of the 100-kilometer sacbe to Yaxuná. The goal of our contemporary survey was to assess and confirm the civil and structural engineering technology used in the construction of the roadway, and establish the route using ground-based GPS positioning instruments, photography, satellite images, and aerial surveys. Furthermore, our investigation carried out observations and took photographs of the ruined sacbe at each terminus, intersections at Sacbe No. 3, and at intermediate crossings of modern roads.

The 1934 survey was a work of a brave and intelligent man. With his crew of 12 men, he hacked his way through the 100-kilometer route and provided archaeology with an overview of the complexity and efficiency of the sacbe system. Our contemporary survey was not required to carve a path through the jungle, but used digital tools, computers, aerial survey, and remote sensing by NASA satellites to observe, measure, survey, and collect data from high above the ancient roadway. We did not attempt and cannot match Mr. Villa’s courage and fortitude. However, the comparison of Villas traditional jungle survey and O’Kon digital surveying combined to provide a new insight to the ingenious Maya road system.

The 1934 Carnegie Institution Survey of the Route

The original survey was the brain child of Villa, a member of the Carnegie Institution of Washington archaeological team working at Chichen Itza. Villa had previously explored portions of the Cobá to Yaxuná sacbe, but had not yet traveled the entire 100-kilometer route. At this time archaeologists were unsure if the road connected Cobá to Chichen Itza or to Yaxuná. Villa discussed his knowledge and experience of this paved road with Dr. Sylvanus Morley, then in charge of the Chichen Itza project. Morley charged Villa, a surveyor, with the mission of exploring and surveying the route from Yaxuná to Cobá.

The survey team was composed of Villa and 12 men; 10 men were assigned to cut a path through the thick vegetation engulfing the route of the sacbe; one man led the horses transporting the provisions, equipment, and water; and another man assisted Villa with surveying measurements and photography. Villa’s survey tools consisted solely of a handheld Brunton compass, a tripod, a 100-meter-long chain or measuring tape, and a range pole for back sighting. The Bruton compass is a precision instrument and can be leveled to increase accuracy. It is an adequate surveying device for surveying compact archaeological sites, but is challenged when required to accurately survey over long distances.

The survey team began its work on February 27, 1934, and proceeded from Yaxuná toward Cobá. The beginning of the sacbe at Yaxuná was marked by a ruined mound located in the center of the city. A stairway, located on the east side of the mound, served as a survey benchmark. At this point, the sacbe was measured to be 10.3 meters wide and 60 centimeters in height. The actual height was probably greater, but the debris of a millennium reduced the wall measurement. The structure of the sacbe at Yaxuná had been badly deteriorated, mostly due to locals using the structure as a quarry. The survey continued over the entire route of the road. As the Villa expedition cut its way over the roadway, Villa noted locations of the villages of Sisal, Sacal, Ekal, San Francisco, and Xcahumil. Villa recorded and photographed stone mile markers, culverts, ramparts, and archaeological structures. One of the interesting discoveries was a cylinder of solid stone that Villa referred to as a “road roller.” The stone was 4 meters in length and 70 centimeters in diameter, with a weight of 5 tons. There are various opinions that have been made about its usage, including a phallus symbol and a method of transport for large stone material.

The sacbe maintained a height of average 75 centimeters as the survey moved eastward. However, at a deep depression, the wall height increased to 2.5 meters. Overturned trees along the route exposed the interior and confirmed the construction of the sacbe: it has vertical sides of roughly dressed stones, large undressed stones laid in a mixture of cast-in-place concrete, smaller stones form the bed, and the roadway surface is paved with cast-in-place concrete.

For the majority of the route, the sacbe travels in a straight alignment following the topography of the terrain (Figure 9-3), only varying a few degrees from the easterly bearing for a few kilometers, then re-adjusting back to eastward. As the route neared the ancient city of Cobá, the route of the survey turned southeast before entering the city, where the sacbe intersects a north–south Sacbe No. 3. An octagonal plaza is located at this intersection. The plaza and sacbeob form geometry similar to a traffic circle. With a 4-meter-tall, truncated pyramid in the center, the sacbe then enters Cobá and ends at the eastern terminus, in the plaza of Nohoch Mul, the tallest pyramid in the Yucatán. A distance of 100 kilometers and 385 meters had been measured from the benchmark at Yaxuná. The dimensions of the road at the terminus were 9.80 meters in width and 60 centimeters in height. Villa produced a drawn survey map of the route. The map includes a cross-section of the sacbe structure and villages along the route.

It is of interest to note that Villa recorded legends relative to the building of the sacbes. The tall tales were in fashion during the time of his survey. Maya, while marveling at the monumental works of their forefathers, believed them to be the work of magic. They believed that these great engineering works were raised by men with supernatural powers. These men were lords of the elements, who, by means of a special whistle, brought life to stones that arranged themselves into marvelous and beautiful buildings and roads without the aid of human labor. These men were eventually turned to stone by divine punishment and are now the stele with human effigies that are admired in Cobá today.

Figure 9-3: Satellite map of 1934 and 1995 survey results of Cobá to Yaxuná sacbe. Courtesy of Google Earth.

The sacbe from Cobá to Yaxuná was said to be built by a magician named Ez. He performed his work in the dark, and by his magic arts, he caused the 100-kilometer road to be constructed in one night. He was so absorbed in his work that when he arrived in Cobá, he was surprised by the dawn and was turned into a stone statue. For the Maya, Cobá is a mythical place where one encounters many dangers. The terrible Hacmatz is a ghastly creature who waits patiently in the jungle by the dark of night; this animal consumes the bodies of men. The unaware who venture in Cobá after dark are devoured, as the Hacmatz entraps them by sticking out its tongue and snaring its prey.

The 1995 O’Kon Expedition to Explore the Cobá to Yaxuná Sacbe

Solving the mystery of the Maya sacbe system has been the keystone to understanding the relationship of Maya road technology with the wealth and power of the Maya city-states. The existence and extent of the sacbe system has been doubted by archaeology for more than a century. In 1995, I assembled an archaeo-engineering team to investigate the Cobá–Yaxuná sacbe and verify its character and existence. The study included the evaluation of the sacbe alignment using global positional coordinates at various locations along the route, including the termini at Cobá and Yaxuná and at intermediate points in the route.

The team consisted of three professionals who traversed portions of the sacbe at each end and at the midpoint. We were not required to suffer 20 days of hacking our way through the jungle undergrowth using a hand-held compass, tripod, and 100-meter measuring chain. We did not use our machetes and did not require a horizontal line of sight for surveying, but used a Trimble global positioning system (GPS) navigation receiver, as well as state-of-the-art (film) cameras. I was accompanied by archaeologists Dr. Nicholas Hellmuth and Carl Stimmel. We had worked together previously on deep jungle archaeological expeditions and had a proven track record. The scope of work that would verify and expand the work of Villa included the use of GPS positioning equipment at the Cobá terminus, the crossing of the Cobá–Yaxuná sacbe and Sacbe No. 3, and GPS readings at the intersection of Modern Highway 195 south of Valladolid and at the benchmark at Yaxuná. The four locations for the survey were selected for their critical locations on the sacbe route and their accessibility. Following are the locations and their characteristics.

1. Survey Location No. 1: The terminus at Cobá. The sacbe is consolidated and the road terminates at a position at the south front of Nohuch Mul. This is the highest pyramid in the Yucatán. This location was obviously the central plaza in Cobá. Four other sacbe from the cardinal directions terminate at this large plaza. GPS readings and photographs were recorded.

2. Survey Location No. 2: The intersection with Sacbe No. 3. The Yaxuná sacbe extends westward from the plaza for approximately 700 meters to the intersection with the north–south Sacbe No. 3. A unique traffic control system was constructed at this intersection. The traffic at this intersection should have been significant. The flow of traffic on the major Yaxuná Sacbe No. 1 and the long-range Sacbe No. 3 merged and crossed at this intersection. The sacbeob ramped up 5 meters to the center of the intersection and formed a level platform. A 4-meter-tall, truncated pyramid is located at the center of the intersection; a tunnel sized for the passage of one person traverses the pyramid in an east–west direction. This passage could have been part of a defense system. The platform extends outward from the perimeter of the pyramid, forming a basic traffic circle. This configuration of road intersection enabled the four lanes of two-way traffic to be controlled by the rules of the road, such as maintaining one-way traffic around the circle and requiring entering traffic to keep to the outside lanes. Without this clever traffic rotary mechanism, the swift movers and heavy-loaded porters would cause a traffic jam. GPS readings, sketches, and photographs were recorded at this intersection.

3. Survey Location No. 3: The intersection of the Yaxuná Sacbe and modern Highway 195. Approximately 57 kilometers to the west of Cobá, the Yaxuná–Cobá sacbe is intersected by modern highway No. 195. This north–south highway cuts through the ancient road, leaving a neat cross section at each shoulder that reveals the technical composition of the road. The 1,400-year-old concrete pavement, stone side walls, and cast-in-place concrete base are clearly visible. GPS readings, sketches, and photographs were recorded at this location.

4. Survey Location No. 4: The terminus at Yaxuná. During this survey the ruined mound that served as the western terminus of the sacbe was investigated. The structure was degraded; however, the ramp of the sacbe up onto the structure was apparent. The sacbe extending to the east was clearly visible for a substantial distance. The site of Yaxuná is a flat plain with elevated temperatures. During the hour-long wait for the Trimble Navigation to acquire three signals, the heat became unbearable. The temperature rose to well over 110 degrees F; there was no shade on the sacbe. We took turns sitting in the shade of the van and studying the ancient city. Across the site, the recently discovered pyramid rose above the plain. Climbing to the summit one can see Chichen Itza 18 kilometer to the north. It was a great spot for Cobá to spy on Chichen Itza or to signal from the promontory. Finally, we acquired the three satellite signals, packed up, and turned the vehicle northward, enjoying the cool 4-70 air conditioner—that’s four windows open while driving 70 kilometers an hour. GPS readings and photographs were recorded at the site.

The results of the survey were assessed and analyzed, and delivered at an architectural conference. However, we knew more work must be carried out to further define the route of the sacbe.

The 2000 Ground Survey of the Cobá to Yaxuná Sacbe

During the period of 1995 to 2000, the site of Yaxuná was consolidated, and archeological work was ongoing at Cobá. It was determined we should verify the 1995 GPS readings in relation to the consolidated structures. In addition, photographs of the newly consolidated structures are important to the history of the sacbe and the ancient cities. The GPS receiver used for this survey was a Magellan eXplorist, and the cameras were now digital. The second archaeo-engineering survey was carried out by a team of two professionals: me and anthropologist Carol Smith. The goal was to take GPS readings and photograph the recently consolidated sacbe and structures at Yaxuná. The observation tour initiated at Cobá and followed the same pattern as the 1995 survey.

1. Survey Location No. 1: The terminus at Cobá. The condition of the terminus sacbe had been altered. The end of the road had been consolidated. All other elements at the terminus were the same. GPS readings and photographs were recorded.

2. Survey location No. 2: The intersection with Sacbe No. 3. The condition of the intersection and pyramid had not changed since 1995. GPS readings and photos were recorded at this location.

3. Survey location No. 3: The intersection of Yaxuná–Cobá sacbe and Highway 195. The sacbe cross-section was overgrown with vegetation, but the condition of the structure had not changed.

4. Survey location No. 4: The terminus at Yaxuná. The appearance of the site had changed dramatically since 1995. The majority of the site structures had been consolidated, including the use of painted stucco on the surface of the structures. The quadratic terminus building had been restored; the sacbe had been reconstructed and paved as it ramps up onto the structure. GPS readings and photos were recorded at this location.

The results of the GPS readings at all points were identical to the readings taken with the Trimble in 1995. It appeared that while the technology had changed, the results were the same.

The 2001 Aerial Survey of the Cobá to Yaxuná Sacbe

The 1995 and 2000 surveys were ground-based and traversed critical sections of the sacbe to verify the alignment, positioning, and technological constructions. After the year 2000, remote sensing by satellite photos for the area between Cobá and Yaxuná was commercially available. However, cloud cover on the mosaic satellite images obscured much of the route and did not permit sufficient clarity to detect the alignment of the road beneath the cloud covered expanse.

The remote-sensing photographs were not an option, due to their obscurity in order to visually trace the route. It was determined to fly an aircraft at low levels along the route of the sacbe from Cobá toward Yaxuná. The goal was to photograph the alignment and structure along the 100-kilometer route. Though I hold a private pilot license, it was decided to lease a chartered twin Cessna from Cancun International Airport. Flying an aircraft with your knees while photographing is a young man’s game.

The flight took off from Cancun International and turned southwest toward Cobá. As we neared Cobá and the tall pyramid of Nohuch Mul approached, the pilot punched Yaxuná’s global coordinates into his avionic system and set the Cessna on autopilot. As the aircraft slowly banked to the west, we flew over the terminus of Sacbe No. 1 and set a westerly course for Yaxuná. The sleek Cessna followed the course established by signals beamed from the manmade celestial bodies orbiting the earth. It was ironic that our pathway would be led by the same philosophy that guided the ancient Maya. However, ours was a digital signal and not cosmic.

I was surprised how the sacbe revealed its course in various ways. The rainforest had been cut for agricultural purposes along lengths of the sacbe. Grass-covered fields prepared for cattle ranches extended to a line of tall trees that were approximately 10 meters in width on the south side the grassy glades. The pathway of the sacbe was clearly marked by the line of trees that extended to the horizon (Figure C-21). Beneath the trees lay a 10-meter-wide and 1-meter-tall mass of stone and concrete, more trouble to remove than to leave in place. This left the concrete structure and the trees on the sacbe. The tall trees were the markers for the ancient roadway traversing the terrain. The aerial photograph Figure C-21 clearly indicates the alignment of the road from Cobá to Yaxuná.

The sun glinted from the white stucco on the monumental structures as we neared Yaxuná. The ancient road and its elevated terminus clearly marked the restored sacbe climbing up the terminus structure. The aircraft orbited the site several times, photographing the sacbe, and then turned due east toward Cobá. Returning along the ancient sacbe route, the pattern of the ancient road replicated itself. Soon Nohuch Mul appeared on the horizon and we crossed over Cobá’s lakes. Our aircraft then turned toward Cancun International Airport and home base.

Comparison of the Technologies of Survey Equipment

It is interesting to note the great difference in technology achieved between the dates of each survey date. It was assumed that the leap in technology between 1934 and 1995 would make a vast difference in capabilities, and so it was. No longer did we labor with a line of sight survey and machetes; the GPS freed us from the tortuous trek. However, the difference in technology during the short period between 1995 and 2000 was surprising not only because of the advances in survey equipment, but also of that in cameras and cell phones. Our GPS receiver in 1995 was a relatively large, handheld device with an antenna consisting of a long wire lead. It required acquiring signals from a minimum of three satellites to receive a reading of a two-dimensional global position, and signals from four satellites to receive the ground elevation. In 1995, the wait time to receive signals from three coincidental satellites in the Yucatán was lengthy. During that time period, not many satellites were over passing the Yucatán. We’d receive one signal, then two, then zero, then one—and so on until an hour had passed and the screen indicated acquisition of three signals. Success! We hooted and hollered, “We got three!” There on the screen was our global positioning reading. This lengthy sequence took place at all four locations of the survey. Our cameras used high-speed-film and our cell phones were attached to our cars back home.

The GPS readings in 2000 verified the readings recorded in 1995 with similar coordinates relative to the alignment of the road. It is here that we note the advances in technology that occurred in the five-year period. The GPS receiver used in 2000 was a Magellan eXplorer. In addition to providing global positioning coordinates, this small, handheld device had many other features of significance to the archaeo-engineer in the acquisition of signals. In 2000, we acquired the signals from six satellites in five minutes rather than the hour-long wait in 1995. In addition, technology advances enabled our use of digital cameras and laptop computers, versus the celluloid-based cameras used in 1995. Our telephones were in our pockets rather than patiently waiting for us at home.

The loop had been closed. Villa’s courageous and legendary survey trail in 1934 and the O’Kon surveys of 1995, 2000, and 2001 had confirmed and verified that the sacbe was a monumental engineering effort. Our intentions had been the same while the available technology had changed. We relied on celestial orientation for positioning our strategic points, and celestial navigation to fly the route. It is interesting to note that Maya engineers used the fixed points of the cosmos for celestial positioning, and we relied on celestial guidance of the digital kind.

The Analysis of the Surveys

The 1934 survey was greatly penalized by the lack of appropriate survey equipment. Villa was equipped with a handheld compass that was dependent on the variable magnetic north. The magnetic declination in the Yucatán is approximately 5 degrees. Villa could not take global coordinates. His survey, when plotted on a Google Earth satellite image, actually places Cobá some 5 kilometers south of its actual position. However, Villa is a true hero of archaeology. He and his team hacked their way though the 100.33-kilometer route of the sacbe. He substantiated without a doubt the true goal of his mission: to prove that the sacbe did exist and that it terminated at Cobá. He reported on the nature of the construction of the road and artifacts along the way. He prepared a report that, even in the 21st century, is unparalleled in the narrative, graphics, and photographs of a survey for a sacbe. His drawing of the survey indicates the complete route with stations of the road and villages along the way. He exceeded the goals of his mission and stands today historically as the sole author of a complete visual, graphic, and narrative published document relating to in situ sacbeob. The accuracy of the measurements is not of great importance. The real achievement of Villa’s expedition was the proof of Maya technology.

The graphic results of the 1995 survey using the GPS positioning data are indicated in Figure 9-3. The 2000 survey verified the readings at all four points indicated a bearing of 269°58’ 32.4” between Yaxuná and the intersection of the Yaxuná–Cobá sacbe and Sacbe No.3. This is 99.992 percent accuracy for an east–west line between Yaxuná and the entrance to Cobá. If a true east–west line were extended from Yaxuná to Cobá, it would miss the target of the terminus by only 87 meters. It is noted that the sacbe on the Carnegie Institution survey deviated at several points from a straight alignment. However, the alignment of the start and finish of the road is unique. The length of the route was calculated to be 98.45 kilometers using global coordinates, versus the 100.336 kilometers surveyed by Villa. The global-coordinated calculations used a straight line to determine the length between points. The Villa measurements indicated slight turns in the route of the road, which would require a longer distance between points. Villas measurements of the exact road may be more accurate, but it would take a ground survey to verify the actual distance. Our aerial survey in 2001 verified the actual route of the sacbe. This alignment is indicated on the satellite image (Figure 9-3); the actual alignment was based on the tracking study carried out on the Google Earth image.

In summary, the 1934 survey verified the route and characteristics of the route. O’Kon surveys verified the unique east–west alignment of Cobá and Yaxuná, and the course of the road as it traversed between the two ancient cities. It sometimes deviated from a true east–west course, but always returned to the east–west line of the route. The route between Cobá and Yaxuná did exist and connected the two cities on a true east–west direction.

The existence of various forms of sacbeob in the Maya world has remained in folk memory and includes mythological roadways, celestial skyways, and subterranean routes. This search, however, seeks the lost road from Mérida to Cozumel, and is confined to observable and measureable terrestrial roadways that are the result of technological achievements of Maya engineers. This most intriguing of the mystic terrestrial sacbeob is the legendary path of pilgrims that extends from the city of T’hó, today’s Mérida, in the Yucatán, to the east coast and on to the Island of Cozumel. This sacbe presents more tantalizing clues of its existence than any other example of Maya roadway. This fabled road extended 285 kilometers from T’hó eastward to the Caribbean coast and the city of Puerto Morelos. From this port, pilgrims would embark on seagoing vessels for the sacred crossing to the Island of Cozumel and the opportunity to worship at the temple of Ixchel. She was the goddess of the moon, fertility, midwifery, medicine, and magic. Ixchel was a woman’s goddess. The temple of Ixchel had a long history; it has been determined that her temple was an active and popular shrine from 100 BC until the conquest during the 16th century. Millions of the faithful traversed the sacbe and made the sea passage. Maya women visited the shrine at least once during their lives, coming from distant points in the Yucatán, Guatemala, and Honduras.

In modern transportation planning, a “desire line analysis” is a study that plots the desired destinations of travelers and the volume of traffic to certain points. The analysis is used to plot and plan the routes of proposed highways. If one was to plot the desire lines of Maya pilgrims from the major cities in the Yucatán to the port of departure for the sacred voyage to Cozumel, the route of the pilgrims would extend from major Maya population centers directly to the coast of the Caribbean.

The legendary highway was more mystical than mythical, but it had many real and practical applications in addition to the travel of pilgrims over the 285-kilometer roadway, not only to the shrine of Ixchel, but to the holy city of Izamal, where faithful visited the birthplace of Itzamna, the Maya God of wisdom, art, and languages. The passage of pilgrims, plus the commercial and administrative traffic between the largest cities in the Yucatán, made this a very popular route.

The existence of the long mystical sacbe has been reported since the 16th century by Spanish chronicles, and traces of the route have been investigated by explorers and archaeologists into the 21st century. In the 16th century Bishop Diego de Landa observed that a sacbe extended from T’hó to the ruins at Izamal. In 1688, Diego Lopez de Cogolludo reported his finds on this fabled road in Historia de Yucatán (History of the Yucatán): “There are remains of paved highways which traverse all this kingdom and they say they are ending in the east on the seashore...so they might arrive at Cozumel for fulfillment of their vows, to offer their sacrifices and to ask for help in adoration of their false Gods.”

In 1966, archaeologists Dr. Edwin Shook and Lawrence Roys investigated the 32-kilometer sacbe from Aké to Izamal, 200 kilometers to the east along the same alignment. Geologist A.E. Weidie reported, in 1962, the discovery of a raised bed of an ancient roadway that extended 20 kilometers from Puerto Morelos on an east–west line along the same alignment as the Aké to Izamal route. From 1995 to 2002, archaeologist Jennifer Mathews of FAMSI confirmed evidence of that same east–west elevated sacbe extending more than 20 km to the west from modern Highway 180 at Puerto Morales.

The legend of the sacbe of the pilgrimage route traversing the northern Yucatán persists in folklore, historical accounts, and archaeological investigations. Segments of the route have been mapped and investigated, but the entire 285-kilometer route has not been assembled and assessed in a logical study using global positioning, remote sensing, and satellite imagery until the O’Kon survey of 2010.

The O’Kon Investigation of the Pilgrims’ Sacbe

The route of the sacbe from T’hó to the Caribbean coast has been the subject of historical conjecture since the Spanish conquest. Segments of the legendary route have been investigated, but the complete 285-kilometer route has not been surveyed as a complete road running from Mérida to Puerto Morelos. To physically trek over the entire route using ground-based survey equipment would be daunting for any explorer, in any era. However, with Global Information Systems (GIS) the feat can be accomplished with a minimum of boots on the ground. The GIS system integrates information from digital data received from satellites feeding geographical information into ground-based software and hardware.

The object of the O’Kon survey was to register global positioning data at critical locations along the route of the pilgrims from Mérida to the Caribbean coast. Then the global positioning data was introduced into the GIS software using the system to develop vectors along the path of the road. The vectors will basically map the route. Furthermore, to verify ground features of the route, the vectors will guide the way to the extant vestiges of the ancient road and develop a ground track, and confirm the GIS vector studies and develop a virtual route of the road. The plan for acquiring ground-based GPS readings along the route included strategic points at known positions along the road. These include positions at the salient cities including Mérida, Aké, and Izamal, and points along the road terminus at Puerto Morelos. Traveling by automobile, our team started the ground survey and acquisition of GPS positions in Mérida and traveled east toward the Caribbean coast. GPS readings were taken at the following points:

Mérida: A GPS reading was recorded in the zócalo or central plaza of Mérida.

Mérida: A GPS reading was recorded in the zócalo or central plaza of Mérida.

Aké: A GPS positioning reading was taken at the center of the site.

Aké: A GPS positioning reading was taken at the center of the site.

Izamal: A GPS positioning reading was taken at the zócalo.

Izamal: A GPS positioning reading was taken at the zócalo.

Puerto Morelos: GPS positioning was taken at two locations on the terminus of the road. Readings were recorded at the east and west ends of the 16-kilometer stretch of road.

Puerto Morelos: GPS positioning was taken at two locations on the terminus of the road. Readings were recorded at the east and west ends of the 16-kilometer stretch of road.

Google Earth was used to plot the GPS positions derived from the survey, enabling the plotting of the route from Mérida to Puerto Morelos. Close observation of the satellite imagery along the projected route indicated clear traces of the degraded sacbe at several locations. Evidence of the road was clearly indicated between Mérida and Aké, and between Aké and Izamal. Images of the sacbe were obscured by dense forest for an approximate distance of 100 kilometers. The clear configuration of the sacbe again was revealed 21 kilometers from the Caribbean. The route extends along the road and into Puerto Morelos. Puerto Morelos appears to be the departure point for countless Maya pilgrims to Cozumel.

Analysis has indicated that the weight of evidence from eyewitnesses, historical accounts, survey investigation, and GIS analysis makes its highly likely that the pilgrim road from Mérida to the coast actually existed. Furthermore, the alignment of three ancient cities and the port city exactly along an east–west azimuth and the route of the road is more than coincidental. The bearing of 269.87° 53’ 42” is 98.94 percent accurate compared with an east–west line of 270 degrees. The strong evidence indicates that an east–west alignment along the major pilgrim route begs the question, Which came first—the cities or the road? The parts have been proven to exist; now research must be carried to prove that the sum of the parts is equal to the whole. Though the investigation of the road started in the mid-20th century, this legendary road still requires more investigation to verify the exact path of Ixchel’s sacbe.