For Indians like George Campbell and Watcher McDonald life on campaign was similar to life in garrison. There were differences: meals were more uncertain on campaign and living conditions were primitive, at least by the standards of the Civilized Indians. They spent more time walking and less time riding than they would have preferred. Medical services were inconsistent and field sanitation barely adequate. Units typically marched too quickly for the soldiers to appreciate the country through which they were traveling – assuming that they had the energy to play tourist, and were not exhausted from too much marching and not enough food. Then, too, there was the danger of being shot at, frequently, and when the soldiers least expected it.

Indians of the Civilized Nations generally liked the outdoors. The typical Indian of the Civilized Nations could live outdoors as well as his white counterparts in Texas and Kansas. Most enjoyed hunting and fishing. Ranching – with the attendant drives and herding activities – was a preferred way for a Choctaw or Chickasaw to earn a living. But these Indians were homebodies, not plains nomads. In May 1863 Cherokee Jason Bell, a captain in Stand Watie’s regiment, wrote in a letter home, “How I would like to settle down again and hear the cows lowing, the hogs squealing, and the yard with roses in it, the waving wheat and the stately corn growing...” For men like him, the best way to finish a day spent enjoying the outdoors was in bed at home. Even a barracks beat a night in the open air, especially when the nights were wet or cold.

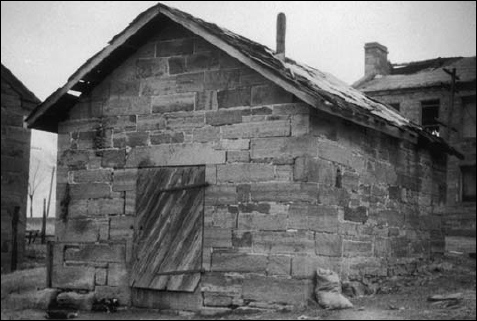

The magazine at Fort Gibson, built in 1845, provided one of the few secure places to store large quantities of gunpowder in the Indian Territory. Prior to Fort Gibson’s capture by the North, it gave the Confederates a place to refresh their ammunition, which in turn was a major reason for the Confederate victory against Opothleyohola’s loyalists. By the third battle with the Confederates, the loyalists were out of gunpowder, while the Confederate troops had plenty. (Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division)

By the fall of 1861 nearly 2,500 Indians were in Confederate regiments. Virtually every Indian unit raised by the Confederacy was a mounted rifle force. Towards the end of the Civil War, the Chickasaw Nation, fearing a shortage of horses, raised an infantry regiment, but this was quickly altered to a mounted unit. The three Indian Home Guard Regiments raised by the Union were organized and paid as infantry regiments, but until they ran out of horses, they fought as mounted rifles.

In the early 19th century mounted rifles filled a niche between cavalry and infantry. Like dragoons, they were intended to fight both mounted or on foot. While dragoons were traditionally armed with smoothbore muskets or musketoons, mounted infantry used a rifled firearm, frequently a carbine. Since a rifle had a much longer range than a smoothbore, mounted rifles were used as skirmishers, who scouted ahead of a main body, then deployed into a skirmish line – dismounted if the terrains supported it – that both fixed the enemy and denied it information about the force opposing them.

The rifled musket, which gave soldiers the range of a rifleman with the rate of fire available to musketeers, eliminated much of the uniqueness of the mounted rifleman. By the Civil War most cavalry were in fact, if not in name, mounted rifles, and fought dismounted when circumstances dictated.

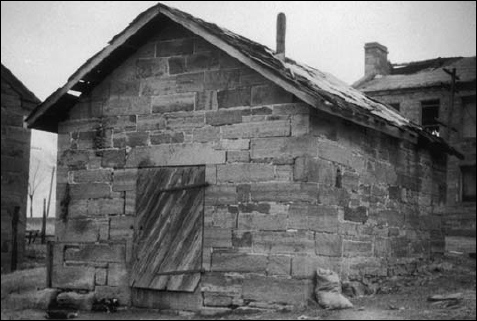

The only overtly loyalist forces were those of Opothleyohola, an Upper Creek chief and, ironically, a slave owner. In his youth he had fought the United States during the War of 1812. That war cemented his loyalty to the United States – or at very least gave him an appreciation for the capabilities of the Federal troops that younger and rasher Indian leaders lacked. He led the Creek faction that opposed union with the Confederacy.

His stand attracted other loyalist Indians – not just Creeks, but also Seminoles and Cherokees – as well as escaping slaves. By the fall of 1861 perhaps 6,000 other loyalist Indians and escaping slaves had gathered around him. Most were women, children, and old men. Opothleyohola appealed to the Federal government in Kansas for aid, but by October, the loyalists realized that the Union was not coming. A Confederate column, consisting of troops from Texas, the Confederate Creeks, and the Choctaw and Chickasaw Regiment commanded by Col. Douglas Cooper, was approaching, so Opothleyohola ordered his people to Kansas.

The loyalist column had 300 runaway slaves and 1,200 Seminole and Creek fighting men – including young boys and old men – for protection. A lack of weapons, limited stores of ammunition, and poor organization handicapped the loyalists. The runaway slaves had neither firearms nor the training to use weapons. Many of the Indian warriors were older men. Few were armed with more than hunting rifles, and they only had enough powder and shot for peacetime hunting. Additionally, the loyalists lacked organization. They came as individuals dissatisfied with the decisions of their various tribes to ally with the Confederacy.

The loyalists fled as families, carrying what possessions they could in wagons and on pack animals. Many brought their livestock with them. The column crawled north and east, a combination of wagon train and trail drive.

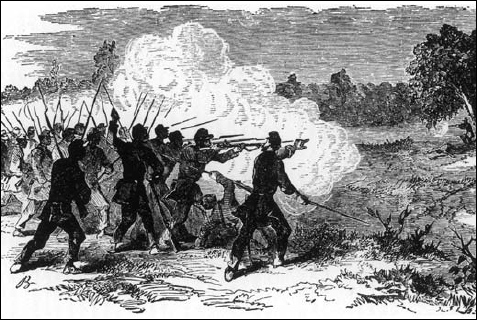

The Confederate forces soon caught Opothleyohola’s people. In three battles fought from late November until the end of December 1861, Cooper’s Texas and Indian forces destroyed the loyalist column. While some Texan forces participated – mainly irregular cavalry – the Opoth-leyohola campaign primarily pitted Indian against Indian. Formal Indian military units organized in European fashion fought against traditional Indian war bands. The European model emerged victorious.

As a young man Opothleyohola fought against the United States during the War of 1812. In his sixties at the outset of the Civil War, he was convinced that the United States would defeat the Confederacy as it had the “Red Sticks.” His refusal to side with the Confederacy thrust him into leadership of the loyalist faction. (Western History Collections, University of Oklahoma Library)

Two Creek regiments, a Choctaw and Chickasaw regiment, and Stand Watie’s Cherokee regiment – made up of Indians that had assimilated European ways, including George Campbell – enthusiastically assaulted their loyalist kinsmen. A second Cherokee regiment, Drew’s Mounted Rifles, which was made up of traditionalist Cherokees – balked. As Albert Pike, the former Indian Agent who then commanded the Confederate Indians, wrote, these men “did not wish to fight their brethren, the Creeks.” Many deserted rather than fight other Indians. Some joined Opothleyohola before the battle of Chusto-talasah.

During this winter campaign, it was harder for the loyalists than the Confederates. The loyalists depended on food and shelter that they brought with them. After Chusto-talasah and Chustenahalan they were reduced to what they could carry. George and his compatriots could get food and clothing from their bases. The cold weather made travel difficult, even for the better-supplied Confederates. A heavy snowfall the day after Chustenahalan deterred the Confederate pursuit of the scattered loyalists. The Confederates returned to warm barracks, as the destitute loyalist survivors trickled into Kansas over the next month.

Confederate Indian units were raised for local defense, and by the terms of their treaty they were to remain within the Indian Territory. Yet there were times that the Confederate Indian regiments were called out of the Indian Territory. The first was during the Pea Ridge campaign in the spring of 1862. Later, Confederate Indian units fought at battles in Newtonia in late 1863 and at Poison Springs, Arkansas, in 1864.

The reactions of the various Indian regiments to these deployments varied according to the personalities of the commanders and the sentiments of the men. At Pea Ridge, most of the Indian units – two Creek regiments (which included an attached Seminole battalion) and the Choctaw and Chickasaw regiment – refused to move, citing a lack of pay. Even after their back pay was received, most of the units moved slowly, unwilling to leave the Indian Territory. Only part of one Creek regiment willingly left the Indian Territory for Arkansas. The two Cherokee units – one regiment commanded by Stand Watie, and another by John Drew – went to Arkansas. Having fought at Wilson’s Creek, Watie’s unit was eager to go. Drew’s men were more reluctant. Apart from participating in a cavalry charge on the first day of battle, they proved unenthusiastic about fighting outside their home region.

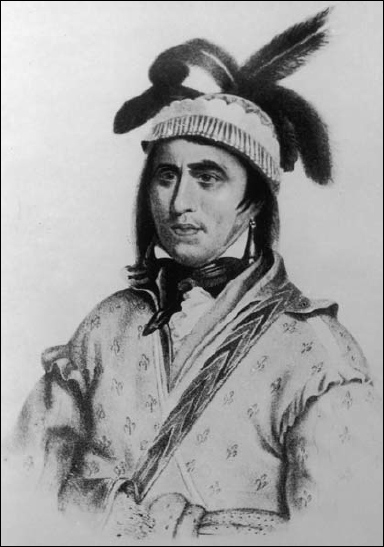

A nighttime bivouac by members of the Union Indian regiments during the First Indian Expedition. (Potter Collection)

This reluctance was motivated, in part, because the Indians regarded Pea Ridge as an attempt to acquire land outside the Indian Territory. It might help the South strategically, but the Indians tended to view it as an attempt to lure them into a war in which they had no interest.

At Newtonia and Poison Springs the pattern was different. Both of those battles were fought to blunt Union drives into the Indian Territory through western Arkansas. The Union had invaded the Indian Territory once by the time Newtonia was fought, and although they had withdrawn, the Indians participated at Newtonia in the spirit that the best place to defend your home was in a back yard other than your own. Similarly, at Poison Springs, the Choctaws and Chickasaw were trying to protect the Red River valley from Union invasion.

The Union Indians were more willing to fight outside the Indian Territory. They started their war in Kansas, and had begged to be permitted to fight. “We had not come here to live at the expense of the government,” Opothleyohola appealed. “Send to us ammunition and transportation as early as possible – we ask no more.” When the Federal government finally raised Indian regiments, they fought wherever they were asked to fight. They preferred fighting in the Indian Territory, but through most of 1862 and early 1863 they were forced to fight outside it, until the Union finally secured Fort Gibson.

Initially, conditions for the two first Union Indian regiments were primitive. They set out from Kansas with no regimental baggage. They lacked tents, cooking pots, and other regimental equipment. They had no surgeons or medical supplies, and were dependent upon the accompanying white regiments for medical care. Watcher spent his nights sleeping under the stars or, when time permitted, in a brush lean-to assembled at the end of the day. His meals on this campaign were equally Spartan. He received biscuit – hard tack – and a piece of raw beef, which he had to cook on a stick over a campfire. By Newtonia in October 1862, the Union Indians had acquired both tents and cooking pots. While conditions improved over the course of the war, the Union Indians seemed to be perpetually at the end of the supply line.

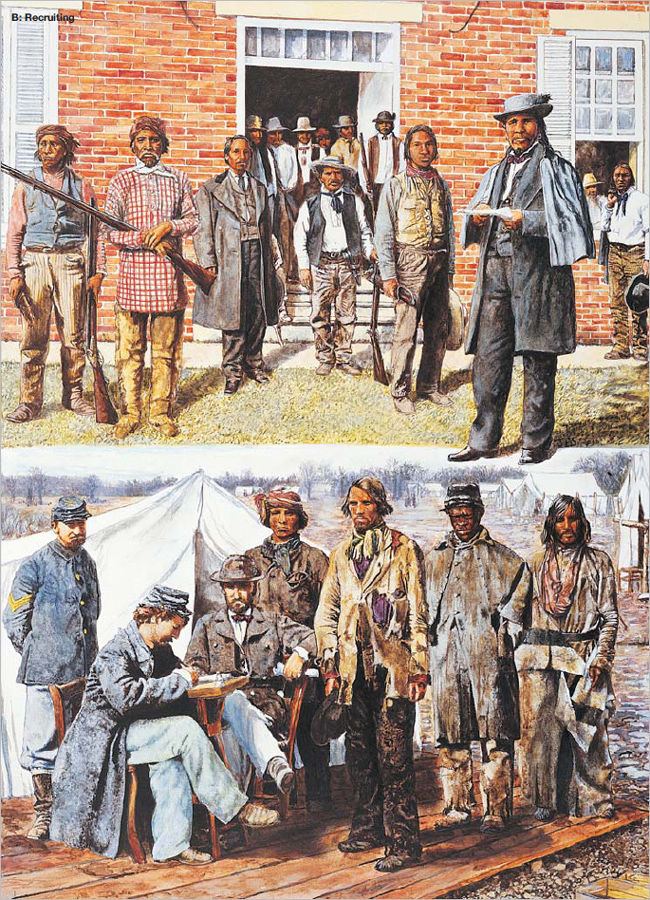

In the field, food would have been weighed out and issued to individual soldiers in a manner such as shown in this illustration. (Potter Collection)

It took two attempts for the Union armies to anchor themselves in the Indian Territory. The First Indian Expedition captured Fort Gibson, and caused the defection of Drew’s Mounted Rifles to the Union, but a pusillanimous withdrawal of white troops by an incompetent commander forced the retreat of the Indian regiments as well. It was not until the spring of 1863 that the Union reestablished itself – this time permanently – in Fort Gibson.

When the Union Army moved south of Fort Gibson in July 1863 the Confederates seized the opportunity to attack the Yankees outside the protection of the fort. Concentrating their forces, the Confederates outnumbered the Northern army nearly two to one.

They struck the Union Army as they were crossing Honey Creek on July 17, 1863. The Confederates overheard an order for Union cavalry, scouting ahead, to fall back. Assuming it was a general order, the Southern cavalry charged into the Union center, anchored by the waiting black troops, lying on the ground. They stood, fired, and demolished the Confederate center. The Indian regiments on the flanks finished the job started by the blacks, destroying the Confederate Army, their last major field force in the Indian Territory.

Honey Springs irrevocably changed the balance of power in the Indian Territory, demolishing Confederate ability to meet the Union Army in the field. The fall of Little Rock, in September 1863, finally allowed the resupply of Fort Gibson by river.

The North failed to exploit its advantages, content to maintain what they already held. Neither Union nor Confederate Indians had enough resources to control the entire Indian Territory alone. The Union and the Confederacy refused to commit more white troops to the region, using their manpower in other theaters. For two years, the region was frequently raided ground.

The Confederates, led by Stand Watie, proved adept at guerrilla tactics. They attacked supply trains, or parties sent to gather hay, and isolated groups of patrolling Union soldiers. The Union forces responded in kind, launching raids into the southern half of the Indian Territory. When Lincoln issued his Proclamation of Amnesty in December 1863, William Phillips, then commanding the Union Indian Brigade, had translations printed in different Indian languages. He distributed the proclamations during a raid in the Choctaw Nation, with a message: accept amnesty or be destroyed. While this action undermined Lincoln’s intention, it reflected the attitude of many of the Indians serving under Phillips.

The exploits of Stand Watie and his Confederate Indians were brilliant and militarily glorious, but strategically sterile. The Confederates could not loosen the Union grip on Fort Gibson. Two years of raids and counter-raids reduced most buildings in the Indian Territory to burnt ruins. At the war’s end, most of the Indian families – both Confederate and Union – lived as refugees, near Fort Gibson, at the fringes of the Indian Territory or the surrounding states.

The destruction was carried out by Indians, against Indians. The whites did not really care about the Indian Territory. The Confederacy wooed the Indian Nations as a way to protect an exposed northwestern flank. As the Confederacy staggered under the hammer blows of the Union armies, the Confederate states became less interested in the Trans-Mississippi region. The Union intervened to ease a refugee problem. As long as the North held Fort Gibson, most of the Indian refugees remained in the Indian Territory, not Kansas. But the internal tribal passions released by the American Civil War consumed the Indian Territory like a prairie fire, as the actions of one side led to reprisals that spurred yet more retaliation in turn.

The battle of Honey Springs gave the Union dominance in the Indian Territory. The Union failure to reinforce this victory condemned the Indian Territory to two years of bloody stalemate. (Potter Collection)

The Indian Territory was a bad place to get injured. Civil War-era military medicine was poor, even at its best, and in the Indian Territory, it was far from its best. A battlefield injury would be treated in an open aid station, set up in a field, more often than not. Field surgery consisted mainly of amputating limbs shattered by bullets.

This assumed the fight where the injury occurred was large enough to merit a surgeon in the field. Most of the combat in the Indian Territory consisted of small raids and patrols. Typically, only a company or two would be involved. Surgeons generally stayed in the garrison unless the entire regiment was committed to battle. An injured man might go hours – possibly days if injured during a deep raid – before receiving any medical attention other than what his comrades could give him on the spot.

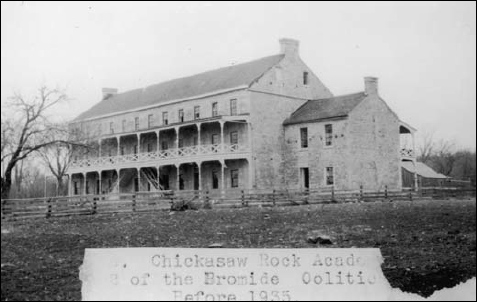

Once he got back to garrison – if severely injured – his troubles were only just beginning. Hospital facilities were inadequate – even by Civil War standards. There were no hospitals in the Indian Territory before the Civil War. During the Civil War both sides used public buildings such as schools or churches as hospitals. Schools were a better option as most of the schools in the Indian Territory were boarding schools, with both beds and kitchen facilities. While they could draw upon the doctors and surgeons in the area to provide basic medical services, they lacked nursing staff.

If you were lucky, a family member would look after you. When George Washington Grayson, a lieutenant in the Creek 2nd Mounted Rifle Regiment contracted smallpox, he survived only because his mother came to the hospital where he was being kept and stayed with him to tend to his needs until he recovered.

Combat injuries were not the major cause of death among the soldiers of either side: disease was the real killer. Of the 1,018 Indians who died while enrolled in the Union Army, 775 – three-quarters – died from disease. Only 107 were killed on the battlefield or died of wounds received in battle.

The Chickasaw Rock Academy was one of the public schools in the Indian Territory. During the Civil War, the school was closed and the academy was used first as a barracks and then as a hospital. (Western History Collections, University of Oklahoma Library)

Being taken prisoner was chancier than avoiding injury on the battlefield. Confederate Indians rarely took Union Indians prisoner. Watcher’s chance of being taken prisoner was better than the Kee-too-wah members that fought the Confederates outside the structure of the Union Army. These free agents were termed “Pins” or “Shucks” (see page 48) by the Confederates, and were shot out of hand if caught.

If Watcher were to be captured he might be treated as a prisoner of war – if his captors belonged to organized Confederate units and not one of the many irregular bands such as Quantrell’s marauding the Trans-Mississippi. Watcher’s chances were better if a white unit from Texas or Arkansas were the captors because they had less emotional investment in the war in the Indian Territory. Many of the soldiers in the Indian Regiment viewed the Union Indians as traitors, even those in organized regiments, and disposed of them on the spot.

Should a Union Indian be taken prisoner, a bleak fate awaited him. He would be sent to a prison camp at Tyler or Marshall, Texas. While the Texas camps lacked the cruelty of Andersonville, life in them was hard. They were overcrowded, and Confederate shortages of both food and clothing in northern Texas were felt most keenly by the inmates of those camps. They got what was left after everyone else.

Life was easier for captured Confederate Indians. Unless they were taken by white Jayhawkers from Kansas or the Indian guerrillas seeking personal revenge against the Confederate Indians, their surrender was likely to be accepted. Captured Confederate Indians were generally sent to the Union’s prison camp at Alton, Illinois. The surgeon of Drew’s Mounted Rifles was sent there after being captured at Pea Ridge.

Confederate Indians taken prisoner often ended up in the prisoner of war camp in Alton, Illinois, but some captured Choctaws ended up being sent to Fort Columbus in New York City, pictured here. (Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division)

The status of Confederate Indians taken prisoner was unique. Technically they were the only prisoners captured by the Union that were not in rebellion. They belonged to sovereign nations that had formally declared war on the United States. Possibly as a result of that, in May 1863 at least one group of Choctaw Indians was sent to Fort Columbus in New York harbor.

Conflict continued in the Indian Territory until the end of the Civil War – and beyond. Confederate forces west of the Mississippi were the last to get the word about the defeat of the Confederacy, and the last to disperse. Kirby-Smith, commander of the Trans-Mississippi District, never really surrendered, and simply sent his men home in May 1865. The Indian forces in the Indian Territory were the last Confederate forces to disperse, continuing resistance until June 1865 before surrendering.

For both George and Watcher, hardship did not end with the close of the Civil War. Both of their homes were in ashes. Confederate Cherokees had burned Watcher’s small cabin after the First Indian Expedition withdrew from the Indian Territory in 1862. The plantation belonging to George Campbell’s family, the home in which he had grown up, and in which he was living at the beginning of the war, met a similar fate in the winter of 1864. Members of the Union Indian Brigade destroyed every building after George’s father refused to accept Lincoln’s amnesty. By that time, George’s family was living with distant Choctaw cousins near the Red River.

Rebuilding was complicated because the Indian Nations had formally declared war on the United States, and peace required them to sign treaties that cost each nation land and money. Watcher’s cabin could not be rebuilt because it was located on land the Cherokee Nation ceded to new tribes as part of the peace treaty the Cherokee Nation signed in 1866. As these new Indians came to the Indian Territory from the Great Lakes region, Watcher was forced to build a new home elsewhere if he wanted to remain in the Cherokee Nation.

After the surrenders of Lee’s and Hood’s armies, the Confederacy still had an effective army in the Trans-Mississippi District, commanded by General Edmund Kirby-Smith. On May 26, 1865, Kirby-Smith (pictured here) sent his army home. This included all of the Indian regiments except for those commanded by Stand Watie at Doaksville. (Author’s collection)

The Campbells were more fortunate. They could rebuild in their old location. Even then, their task was daunting. They had lost all of their possessions, except for a wagonload that they had taken with them to the Red River. Their livestock was gone. The money and tools they had brought with them when they had relocated to the Indian Territory in the 1830s had been destroyed by the war. Since Mr. Campbell’s slaves had been emancipated, they lacked a labor force – except family.

Unlike many Cherokees, Creeks, and Seminoles, the Campbells and McDonalds – or rather the sole McDonald, since Watcher had been orphaned in 1860, when both parents had died of disease – decided to put the war behind them, and work together. Watcher helped his cousins build their new homes, and George helped Watcher build a new cabin.