You picked up this book in the bookstore or ordered it off the website for a reason. Maybe you’ve read our previous books, or you liked the gorgeous picture on the cover, or you were attracted by the odd title, or something in the jacket copy interested you. But we bet you’re still not quite sure exactly what this book is about — because it’s a difficult topic to talk about: a lot of the words we use mean different things to different people. So we want to spend this chapter talking about what we’re trying to do in this book, and some of the pathways that led us to write about such a jungly, resistant, hard-to-write-about topic.

Between us, we’ve been doing SM, or BDSM, or kink, or leathersex, or whatever-you-like-to-call-it, for a bit upwards of half a century (Dossie started in the early ‘70s and Janet in the mid-’80s). For each of us there came a time when we realized that we were having experiences that went beyond the kind of generally wonderful times we’d come to associate with genital sex, and beyond those we’d experienced during our ordinary SM. These experiences were hard to talk about – they had some features in common with psychedelic experiences, some with trance states, some with what we’d heard about tantric practices, some with the writings we’d read from ecstatic mystics of other millennia.

We began to hear from, and talk with, other pioneers of our own communities who were exploring similar avenues during solo practice, partnered play and in groups. We started exploring other embodied spiritual practices like tantra and trance dancing, investigating other sacred sex communities, reading scientific studies on the neurophysiology of spiritual experience and the anthropological background of the uses of pain as a transcendent and spiritual practice, and poking around in writings by various Western and Eastern philosophers about ecstasy and interpersonal connection, wisdom and magic.

In other words, we started getting serious about this stuff. And, of course, we got seriously into our favorite form of research: we started playing with each other and with our friends — a whole lot – to see what we could learn from it. (Hey, it’s a filthy job, but someone has to do it.)

So here we are – nearly three years later, considerably better read, with a lot of very hot scenes under our belts (and between our eyes, and up and down our spines, and at the center of our chests) – and still having a hard time putting into words exactly what this book is about. But we’ll do our best.

Transcendence is, pretty much by definition, a state of being beyond words. Books are, pretty much by definition, made of words. You could say that this situation created some difficulties in writing this book – if you were prone to vast understatements.

To make matters even more complicated, Janet and Dossie use different words to talk about radical ecstasy. Janet prefers words that don’t have historical connections to religion and that at least sound rational; Dossie prefers to redefine, or in many cases undefine, words that have been in use for centuries, and is fond of the language of poetry.

And each and every one of you reading this has your own history and experience and prejudices about words, perhaps especially about words that have to do with spiritual or exalted or transcendent experience. Some words may feel right to you, others may push your buttons; and it’s almost certain that those sets of words aren’t going to match up to the next guy’s sets of words, and probably not to ours.

Here’s what some of the philosophers and authors whose thinking we like have had to say about words:

The Tao that can be named is not the Tao.1

– Lao Tzu

If we threaten the word, we threaten ourselves. Until now, it is through verbal language that we have learned to understand the world. And we understand it badly. By assassinating verbal language, we are killing the father of all our confusion. Finally we shall be free. This is not only true of theatre. We will be free men in every aspect of our lives.2

– Antonin Artaud

All the things you can talk about in anyone’s work are the things that are least important. It’s like the ballet. You can describe all the externals of a performance — everything, in fact, but what really constitutes its core. Explaining something makes it go away, so to speak; what’s important is what’s le ft over after you’ve explained everything else.3

– Edward Gorey

drive dumb mankind dizzy with haranguing — you are deafened every mother’s son — all is merely talk which isn ‘t singing and all talking’s to oneself alone.4

– e.e. cummings

Now, we make our living writing about BDSM and sex. It’s pretty easy to describe the difference between the part of the butt that it’s OK to hit with a heavy wooden paddle and the part you can only hit with a slim rattan cane. But we’ve never been able to write about the time that the shape of the inside of Janet’s mouth turned into a giant bubble, and every stroke of the flogger turned it into a different shape – one stroke huger than the whole house, another stroke the size and shape of a toothpick – and reading this sentence makes us realize there’s a very good reason for that. In this book, we will often attempt to convey how a sex/SM/ecstatic experience feels (or tastes or smells), in an attempt to write around things that can’t, and possibly shouldn’t, be completely or adequately described in words.

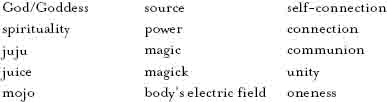

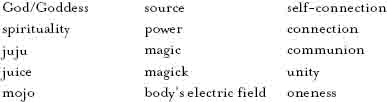

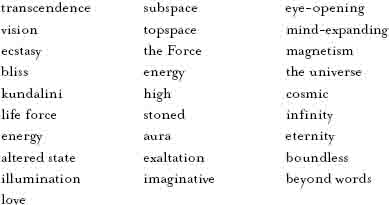

We asked the participants in one of our workshops to list all the words they could think of that meant transcendent states to them, and in just a couple of minutes they came up with this list:

And that’s just scratching the surface – we bet you could come up with a dozen or two more if you thought about it for a while. (It might be an interesting exercise to write your own list, and it might come in handy later on if you find yourself having trouble with some of the language that we use in the book. Feel free to substitute your favorite words for ours anywhere you like.)

We’ve kicked around all of these words and more. And those are just the names of the main topic we’re writing about — that’s not even getting into words for what we want to say about it, or how we do it, or how it feels once we do it, or the even more difficult question of who we are while we’re doing it.

All of the words are partly right, but none of them is completely right, and every single one is going to shut down or turn off or annoy some percentage of the people we’re trying to reach with this book.

Even words we like may not mean to us what they may mean to you. “Spirituality” doesn’t mean the same thing to Dossie that it does to Janet, who keeps saying she’s not into spirituality – but when she describes what she is into, Dossie cries, “But that is spirituality!” “Energy” can mean anything from what the copywriters say you’ll get from their latest breakfast cereal to the force that sets your body afire at your lover’s touch. All in all, we’d much rather come to your house and show you what we’re talking about – but we can’t figure out a way to do that for seventeen bucks.

So, frustrating as it is, we’ve reconciled ourselves to the reality that we’re stuck with the written word for now, and we ask your patience as we slog our way through the difficult task of trying to figure out terminology that we (and you) can live with. You’ll notice that we don’t always use the same words to describe our experiences – we want there to be plenty of different ways to talk about radical ecstasy so that plenty of different people can find some language that fits for their own experiences.

Given that this is a relatively new area of discussion within the BDSM and sexuality communities, its vocabulary is still brand-new. New language will evolve, and someday this volume, and our struggles to find the words for what we’ve experienced, may seem primitive — and we suspect that the cosmos will continue to defy definition in twenty-five words or less.

One of the problems we have with many of the world’s religions (and their secular friends, sciences and philosophies), is that they too often leave no room for mystery. In professing to have a monopoly on the truth, especially about phenomena that cannot be seen or heard, they lose tolerance for ambiguity and fail to honor the unknown — those things that cannot be fully comprehended with human minds or brains.

We humans have trouble tolerating blank spaces. We feel anxious, insecure. We want to fill in the blanks – like when your friend, driving (you think) to meet you, is seriously late, and you call the Highway Patrol because you are sure that they have crashed and are in a hospital somewhere broken and bleeding. That’s a story you made up, a myth. So because these religions/sciences/philosophies are supposed to tell us what is true about the unseen universe, the pundits, not wishing to appear ignorant, have a terrible history of making up stories to fill in the gaps.

A lot of people seem to want answers; we wish to stay with the questions. We treasure the adventure that mystery offers, and answers would cut short the exploration.

So, a word of warning in advance. If you bought this book expecting to be given Answers, now would be a good time to return it to the bookstore before you’ve bent any of the pages or cracked the spine: you’re not going to find them here. However, we hope to offer you some pretty interesting questions.

What does that experience – the one that seems like “more than” orgasm, “more than” SM – feel like? When it happens to us, or to the people we know, the words they use to describe their experiences include “bliss,” “transcendence,” “exaltation,” “spirituality,” “out-of-body,” “out-of-this-world,” “floating,” and a lot more, including the one you see on the cover of this book – “ecstasy.”

The question of what role ecstasy plays in the human organism, and why we’re obviously hard-wired to feel it, is an enormous one. It’s a very, very big feeling, probably the biggest feeling our brains are able to experience. It’s also worth noting that ecstasy is not necessarily a “good” feeling– the dictionary definition of ecstasy is “a state of being beyond reason and self-control,”5 so you can be in an ecstasy of fear, an ecstasy of anger, an ecstasy of pain, or, of course, an ecstasy of pleasure.

In the fascinating book Why God Won’t Go Away: Brain Science & The Biology of Belief6, the authors come to this conclusion from their research:

We believe... that the neurological machinery of transcendence may have arisen from the neural circuitry that evolved for mating and sexual experience. The language of mysticism hints at this connection: Mystics of all times and cultures have used the same expressive terms to describe their ineffable experiences: bliss, rapture, ecstasy, and exaltation. They speak of losing themselves in a sublime sense of union, of melting into elation, and of the total satisfaction of desires.

We believe it is no coincidence that this is also the language of sexual pleasure. Nor is it surprising, because the very neurological structures and pathways involved in transcendent experience—including the arousal, quiescent, and limbic systems – evolved primarily to link sexual climax to the powerful sensations of orgasm.

All well and good – and, we think, absolutely fascinating. Yet the information that we have neural pathways that are capable of perceiving ecstasy, and that those pathways may have evolved from an experience as everyday, clearly understood, and easily accessible as the vibrator on our nightstands, doesn’t change the fact that our knowledge of that ecstasy, and what it might mean, is entirely subjective.

We do not wish to diminish the great mysteries that we travel in when we seek ecstasy. To do so, we feel, would be less than honest, and disrespectful of things that are too great to encompass. Dossie’s favorite prayer is, “Lady, protect me from hubris. “We would rather honor our ignorance, which opens our minds to new revelations.

Radical ecstasy, by the way, is not a particular brand of ecstasy, or a goal of some quest for some form of ecstasy that is better than whatever ecstasy you are currently familiar with. Radical ecstasy is nothing more than an expression that makes a good title for our book, may be because it starts people thinking about ecstasy and about what the roots of ecstasy might be. That’s what radical means, you know– it’s about the roots of things. (It comes from the same origin as “radish.”)

So we can only tell you what radical ecstasy feels like to us — and that’s what we will do in this book. We can’t define it, we can’t encompass it, we can only describe it from our limited perspective, tell you a little bit about what has worked for us, and hope that some parts of your experience hook up to some parts of ours, may be down there at the roots.

When we started to work on this book, we decided to find out a little bit more about tantra. This wasn’t the first time we’d thought about this practice — when Dossie was a wide-eyed eighteen-year-old, someone taught her to imagine the kundalini snake and open the chakras while she was tripping – excuse us, meditating. She’s been using those images during her meditations ever since. Tantra looks to us like another form, along with SM, of graduate school sex. The tantra that you find in California is a westernized form of some ancient spiritual practices that originated in the Himalayas. It employs intense breathing, body movement and intimate connection with another person to raise sexual energy into our genitals, up through the body and out the top of the head.

Why? you may ask. What does tantra have to do with BDSM? The answer, we discovered, is everything. What we found was that the people in the tantra workshops were traveling to ecstasies that felt just like our SM ecstasies, only using different techniques. They were climbing the same mountain up a different side.

The tantrikas we played with were amazed at how fast we “learned.” We told them we’d been practicing for decades, only with whips and chains. And once we were satisfied that tantra was basically the same stuff we were researching, we kept going back because it really works! We’ve added a lot that we learned in tantra to our SM practice – you’ll read more about this soon.

Another fascinating finding in Why God Won’t Go Away has to do with the goings-on of the human nervous system during spiritual and ecstatic experience. Normally, the researchers explain, either the sympathetic (aroused) or parasympathetic (relaxed) nervous system controls the way the body is responding at any given time, depending on the environment and circumstances. However, they can occasionally function together; when this happens, their collaborative effort is called the “autonomie nervous system” :

There is evidence… of cases in which both systems function at the same time when pushed to maximal levels of activity and this has been associated with extraordinary alternative states of consciousness. These unusual, altered states can by triggered by various kinds of intense physical or mental activity, including dancing, running, or prolonged concentration. These states can also be intentionally triggered by specific activities that are overtly religious in nature, such as ceremonial rituals or meditation. The similarities between these intentionally and unintentionally triggered states point to a clear link between the autonomic nervous system and the brain’s potential for spiritual experience.

This feels to us like a very clear description of the relaxed-but-rewed-up way we feel during our ecstatic BDSM experiences. As we move on in this book to describe some of these experiences, perhaps you’ll recognize it as well.

When Dossie’s daughter was newborn, Dossie used to call her “Baby Buddha” because she had not yet completed the first task we learn when we leave our mothers’ bodies — she had not yet learned to tell the difference between herself and the rest of the world. She was still “one with everything.”

All of us spend the first few weeks of our lives working on this problem when we’re not nursing or sleeping, until we get a firm grasp of where we end and the rest of the world begins. And then many of us spend a great deal of the rest of our lives in a frantic scramble to dissolve those walls again, at least for a little while. We may wish to lose track of where we are in space and time. We may want to achieve transcendent oneness with the world and/or with someone we love. We may desire to feel a sense of perfect godlike unity with others, with the world around us, with the universe.

Your authors believe that one of the things that feels so very good about orgasm is that it’s most people’s easiest pathway to something that feels like oneness-with-the-universe: when you’re busy coming, you’re too damn busy to worry about where you end and everything else begins, so for just those few seconds or minutes you get to float (or shimmy, or tremble, or convulse, or scream, or bellow) in a place outside space and time and boundaries. Extremes of sensation or emotion or loss of control that we experience during peak BDSM moments carry us into those same transcendent spaces – this is one of the reasons why scenes that look violent and offputting to outsiders can in fact connect us in a loving and profound way. When we drop our boundaries, we flow into each other.

Similarly, those who practice tantra learn to use their breath, their gaze, their movements and the energies that run through their bodies to carry them into the same boundary-dissolving experiences, into orgasms-that-are-not-genital – experiences that seem to have much in common with our experiences in the dungeon. We’ve both observed that seasoned kinksters who try tantra seem to take to it like ducks to water.

We think most people feel pretty trapped behind their walls and are pretty desperate to escape from them at least some of the time — we certainly are. We’ve found that our experiences in getting rid of our walls have left us feeling happier, sexier, stronger, freer and much much more loving. (And, yes, occasionally kind of scared too, although usually a good kind of scared.)

Once again, we turn to the fascinating research in Why God Won’t Go Away. Brain scans of people having ecstatic experiences during meditation or prayer show that brain activity in the part of the brain that tells us where we end and everything else begins, a section the authors have dubbed the Orientation Association Area, slows to almost nothing – the sense of becoming “one with everything” is reflected in the actual activity in the brain. When we read this, Janet instantly wondered if her lifelong tendency to get lost along the simplest of routes might in fact be one of the reasons she reaches ecstatic states so readily; Dossie had similar thoughts about her severe left/right confusion.

We think that radical ecstasy, as we’ve experienced it, is a way to pull down the walls that keep people apart from each other and from the rest of the universe – just as much as they want them down, and with the people they want to connect with, for as long as they want them down, and for as long as it feels safe. This can lead from anything to fabulous sex – a pretty great goal in itself— to a kinder and more welcoming universe.

A friend of ours once pointed out a fascinating truth: we have no word in English, like “hungry” or “thirsty” or “horny,” for the desire for ecstasy J let’s take a look at why we, and a whole bunch of other enthusiastic players, are looking for paths to transcendence at all. What is it good for?

For starters, it is good because it feels good. Just that. Bliss, divine communion, whatever you call it, feels extraordinary. Even when it feels overwhelming or intense or difficult, which it certainly sometimes can, it still feels different than mundane experience in a way that we often choose to seek out, simply because it is more intense, bigger, more life-affirming.

This amazing feeling is the intrinsic value of the experience. We live in a culture that does not value pleasure or ecstasy – our predominant religions insist that we renounce pleasure in this life and obey religious law in order to be rewarded after we die. We aren’t much taught that we can have divine ecstasy as part of our daily lives. And we are just about never taught that the pursuit of what feels good is a positive force in our lives – most western culture has pleasure as a sin, a distraction, an escape from the terribly serious work of getting to your death in the way that the priests will approve of.

The experience of ecstasy just about always coincides with an expansive feeling of self-worth, of loving the entire universe and ourselves as a part of it, along with a lovely sense of life being validated as a way to participate in something larger, some energy that is larger than each of us. Through that participation, we also get to discover how deeply and lovingly we are connected with each other.

Ultimately, in transcendence we rise above our everyday hassles and frets, get bigger than our judgments (including the harsh judgments we so often apply to ourselves), and experience a sense of wholeness, integrity and just plain rightness which is rewarding in and of itself.

Compared to that extraordinary bliss, any external rewards of transcendent states are almost the icing on the cake – but there are consequences of transcendence that can make our lives work better after our journeys are over for the moment, when we return to more mundane pursuits.

The dissolution of boundaries involved in ecstatic experience means that we can, for a while, expand our vision beyond our everyday paradigms and the limits of our current worldview. When traveling in ecstasy temporarily dissolves our templates, maps, patterns, personal mythologies or belief systems, we can make new associations, incorporate new ideas, see with a vision unclouded by our history. This can lead to new solutions for problems – in much the same way we might search for a solution by “sleeping on it” or dreaming about it.

For instance, as is described later in this book, it was an ecstatic journey that first led Dossie, back in 1969, to look into feminism. In the bright light of transcendent vision, she saw how society’s expectations of her as a woman didn’t fit her. Through the temporary clarity of an ecstatic state, she created a plan to change her life and grasp her power in ways that she had not previously thought possible. Thirty-five years later, as a therapist, an author and an outrageous free spirit, she can report with assurance that it all worked very well.

Sometimes the rewards are smaller and more secular. Janet has had numerous experiences of returning to her mundane existence the day after an extreme and blissful scene, and suddenly finding herself able to solve creative problems on which she’s been stuck for months — a friend calls this “defragging her brain” (after the process of defragmenting the data on a computer hard drive), for the sudden cognitive and emotional clarity it gives her.

Our experience of transcendent states is that they open up our own power in the form of tremendous energy that becomes available to us for whatever purpose we might choose.

So, with all these goals in mind, we set forth to discover the hows and whys of the astonishing experience that we have dubbed radical ecstasy. Welcome to the journey.

1 Lao Tsu, Tao Te Ghing, trans. Gia-Fu Feng and Jane English, Vintage Books, New York, IÇ)J2 ¦

2 Antonin Artaud, in a letter toj. Paulhan, 1932.

3 Edward Gorey, quoted in The Strange Case of Edward Gorey, Alexander Theroux, Fantagraphics Books, 2000.