PLANTATION

PLYMOUTH PLANTERS, when first exploring the area around their village, bemoaned the fact that the recent epidemics had left fertile agricultural land without “men to dress and manure the same.”1 (In this case, by “dress” they meant prepare for planting.) Promoters of English colonization thought that comparatively empty lands in America cried out for the introduction of the idle men of England: “the Country wants only industrious men to employ, for it would grieve your hearts (if as I) you had seen so many miles together of goodly rivers, uninhabited,” while at the same time you “consider those parts of the world where in you live, to be ever greatly burdened with abundance of people.”2 Besides supporting the self-serving assumption that land was freely available for the taking, these observations also anticipated the transfer of English land-use practices to the shores of America. The first migrants to New England understood their project in terms of such a transfer: they wanted to transplant their familiar agricultural practices and social organization. In their terms, they envisioned a “plantation” rather than simply a trading outpost or military installation. While those other models depended on male participants stationed in a location only temporarily, the vision for Plymouth included families that would remain permanently. A plantation from the outset, Plymouth was established with that goal in mind.

The new arrivals embraced the idea that theirs was a plantation. The first published account describing their undertaking frequently referred to the project in precisely those terms. Not only was the work published under the title A Relation or Journall of the English Plantation setled at Plimoth, but the authors and editors sprinkled the term liberally throughout the text as well. Participants in the project were “planters,” not “settlers,” as we often refer to them today. A few years later, Edward Winslow penned another account in the interest of relating, as the subtitle of Good Newes put it, Things very remarkable at the Plantation of Plimoth in New-England.3 When, after a decade, leader William Bradford composed his account of the gestation of their project, he famously titled his record “Of Plimoth Plantation.” After Plymouth was founded, John Smith—a man most commonly associated with Virginia—published his Advertisements for the Unexperienced Planters of New England, referring to Plymouth as a plantation and to those who might venture to the region as planters. In 1669, Bradford’s nephew, Nathaniel Morton, described the “Transplantation of themselves and Families.”4 “Plantation” remained the most common term participants used, a word that described their fundamental goal: the transplantation of English families to a new place. Plantation meant permanence, sustenance, and familiar practices.

To modern ears, “plantation” has a different meaning. We envision a plantation as a large-scale agricultural concern in which European masters lived in luxury while enslaved Africans toiled their lives away in bondage. This definition has led some activists to question the continued use of the term in such names as that of the state of Rhode Island: “the state of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations.” That term does not imply, as its critics suspect, the existence of slave plantations. Prior to the advent of American slave plantations, and for many decades after they were launched, “plantation” carried a broader meaning, that of permanently transplanted groups of Europeans living in families. Edward Winslow, writing general advice for anyone wanting to set up a plantation, listed three dangers: expectation of quick profit, ambitious leaders who make “slaves of all that are under them,” and unqualified men. In Winslow’s warning, the men in danger of enslavement were English men who signed on to help settle a plantation but found themselves bound to an unrelenting taskmaster.5 In his understanding, plantations were perfectly possible and indeed preferable without slaves. They were made up of English people who went as “Tillers of the Earth.”6 Plymouth Plantation and later Rhode Island and Providence Plantations bore the name “plantation” to indicate that they housed English families. Whether or not they held slaves (and initially neither place did), both New England jurisdictions carried the name. The first publication about the effort to establish Massachusetts Bay Colony similarly discussed it as a “New-England plantation.”7 Modern critics can fault them as examples of settler colonialism, intent on taking the land of others for their own purposes, but not, at least initially, for profiting from the mass enslavement of their fellow human beings. The distinction, as far as the term “plantation” is concerned, is one that we have lost but which they fully understood.

Plymouth people were in fact conscious of the problem of taking the land of others for their project. The site where they located their town had been a Native village prior to devastating epidemics (from disease brought by visiting Europeans). The new arrivals learned this history not only through their observations of the land itself but also in conversation with area residents, including Tisquantum, who resided in that village at the time of his 1614 kidnapping. They came to think of the fact that they entered unoccupied land as an important aspect of their experience. It meant their movement into the area (although watched from afar) did not involve direct confrontations over land. Plymouth residents told a visitor in 1624, “Here is not one living now, nor not one living which belonged to this plantation before we came, so that the ground on which we are planted belongs to nobody.”8 Some English observers saw the hand of God in the widespread death that paved the way for them to move into the Wampanoag village site. John Smith remarked in 1622, after hearing reports of the Plymouth settlers, “God had laid this Country open for us, and slain the most part of the inhabitants by cruel wars and a mortal disease.”9 For Nathaniel Morton, it was axiomatic that God swept away the original inhabitants in order to make way for the Plymouth people.10 Whatever God’s intention, moving into land that belonged to nobody was surely an easier proposition than taking the land that someone else actively used and would doubtless defend.

When the English author expressed grief over untended tillable land, he imagined bringing that land under English cultivation practices. Seemingly available lands caused many visitors to think of all the idle men of England who might be employed upon the land. Such observations, published out of Plymouth almost immediately, helped in fact to prompt the schemes to set up other such plantations throughout the region. Although Massachusetts Bay was officially called a “colony” in line with terminology used in its charter, it was understood in precisely the same terms of transplantation. In that regard, Plymouth not only led the way but sent the signal back to England that here was land available for the taking, wanting only “men to dress and manure the same.”

The goal of transplantation assumed the transfer of English approaches to land use. The idea that “the Country wants only industrious men” announced English expectations. While it was true that the initial expeditions into the countryside found places that had once been populated and were currently abandoned, the agricultural laborers who no longer lived to plant and harvest were not Native men, as these observers supposed, but rather women. Native women took charge of planting, manuring, harvesting, and grinding the staple crop that sustained their communities. Men performed all these tasks in England, and the Plymouth people thought such labor an exclusively male province. They brought their cultural assumptions not only about proper agricultural practices but also about gendered labor.

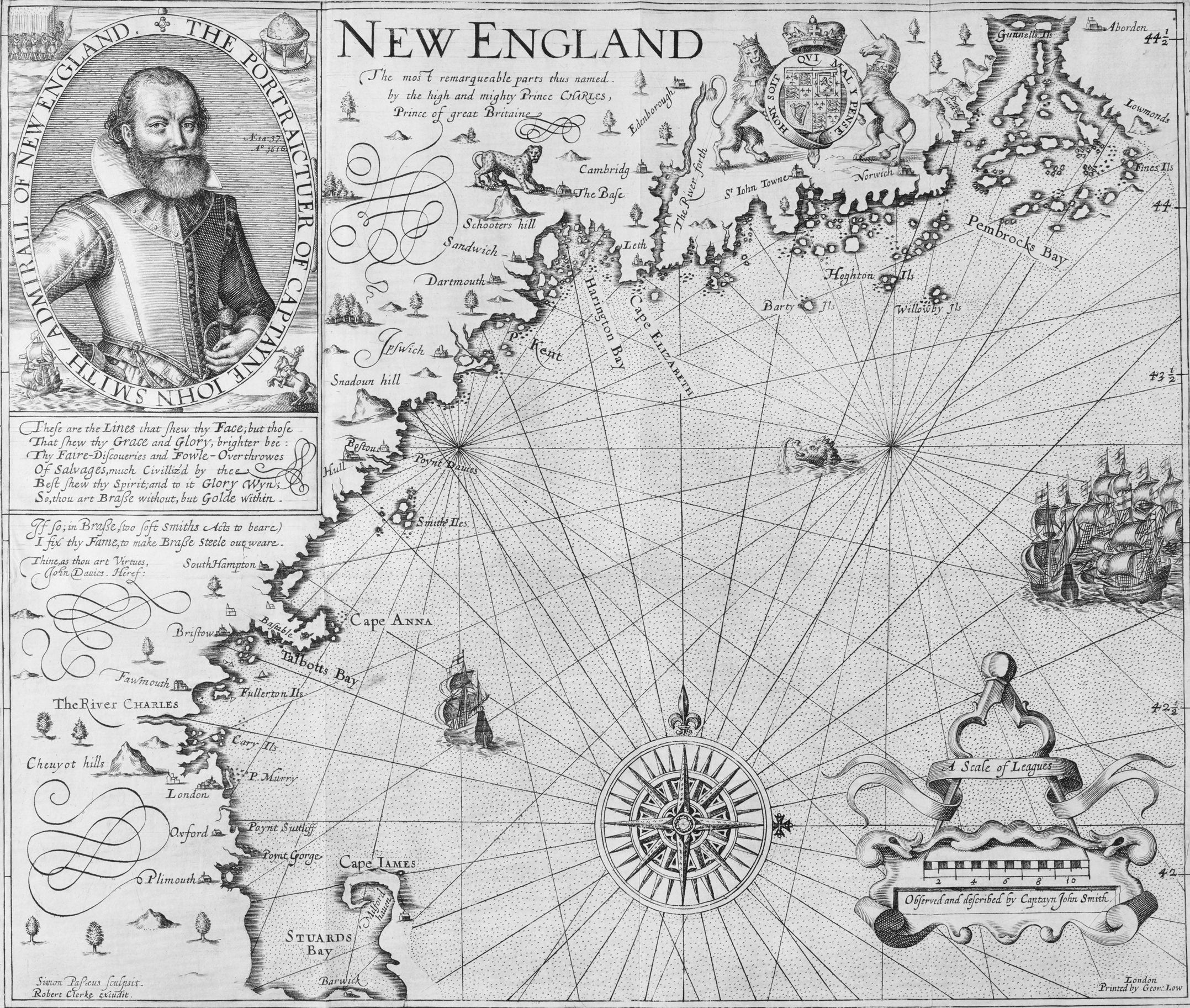

Published four years before Plymouth Plantation’s founding, this map named locations in New England after places or royalty in England. Many of the names never came to be applied beyond Smith’s early map, but Plymouth was an exception. John Smith’s place named for the English port city appeared in the general vicinity of the future village of that name. Clearly Smith, like those who later came to Plymouth Plantation, envisioned transplanting English people to this place bearing (new) English names.

Even as they pursued their goal of transplanting English agricultural practices to the New World—no mean feat since many of them had lived in an urban environment before migrating—their perceptions of Native practices were skewed by their own cultural expectations. Observing Native women doing agricultural work, they decided that the women were being degraded and likened their lot to that of slaves. William Wood, when he wrote an early description of New England, included an entire chapter on the roles of women in Native society. Addressing this chapter directly to English women, Wood expected his female readers to be especially interested in the lives of their counterparts in America. He explicitly instructed them on the lesson he wanted them to take from his description: they should be grateful for their easier lives.11 English men writing about Native people invariably remarked on the difficulty of the work the women among them performed: Edward Winslow, William Morrell, Francis Higginson, and the unnamed authors of A Relation or Journall all noted that Native women suffered the abuse of performing agricultural labor.

The men, in contrast, spent their days engaged in recreational activities, or so declared William Morrell. Like all these authors, he came from a culture in which hunting was reserved for the elite and enjoyed as a recreational activity, so he perceived Native hunting in a similar light. If he had paused to consider the implications of the fact that indigenous people kept no livestock, he might have realized that any meat in the Native diet came of necessity from hunting. Yet so entrenched were expectations of European agricultural practices, with men behind the plow and meat provided by the slaughter of farm animals, neither Morrell nor anyone else pondered the obvious differences. Instead, even when they noted the centrality of women’s agricultural labor—Winslow for one realized that “where are most women, there is greatest plenty”12—they still discounted the complementary and equally important contribution of Native men.

Even as they misunderstood how Native practices differed from their own, the men who wrote about early Plymouth seemed at times to overlook how the effort to transplant English ways affected the women who participated. At times, they appeared to dismiss the work performed by the women in their own communities. Women in Plymouth labored intensively: no clothing was sewn, no food was processed or prepared, no kitchen garden was tended, and no children were cared for without the physical labor of Plymouth’s women. Households could not function without the contribution of adult women, who were trained as girls in the skills needed to feed, clothe, and otherwise care for their families. Remarkably, given the narrative about Native gendered agricultural labor, Plymouth women did sometimes work in the fields. This necessity arose particularly during the plantation’s first years, when food was scarce and laborers few.

A moment in the first year in Plymouth, later remembered and mentioned by William Bradford when he sat down to describe important early events, brought home the occasional invisibility of women’s work. When the first arrivals set up their small settlement, they tried to create household units that would work well given the gendered nature of work roles and skills. Each household had to be headed by an adult male who was responsible for all members—wife, children, servants, and any other residents within the household. Although the Plymouth leaders identified twenty-four distinct families, they decided initially to build only nineteen structures. Thinking to save on the (male) effort of building dwellings, they instead silently added to the expectations placed on women. They directed “all single men that had no wives to join with some Family, as they thought fit, that so we might build fewer houses, which was done, and we reduced them to 19.”13

This policy, besides reducing the number of structures needed, also hinted at (without fully acknowledging) the essential nature of women’s work. Men alone could not easily live without women’s labor. William Bradford later suggested that this strategy—saddling the community’s women with the care and feeding of unrelated men—prompted resentment. Labor that women willingly performed for the benefit of their own families they saw as “a kind of slavery” when it fed and clothed men other than their husbands or his dependents.14 Such resentment might have been particularly acute in this situation, in which the community’s men simply expected the women to cook and clean for anyone placed in their household. In England, it would not have been unknown for households to take in unmarried men, but they usually entered as servants; and the sort of large households that employed male servants also retained the services of female servants who joined in the cooking and cleaning, tasks that in Plymouth under this arrangement fell to these hardworking and exhausted wives. A departure from English practice, the placement of unattached men had been organized without regard for the women’s expectations or indeed for usual household arrangements. That the men in their community did not see them as slaves—even if the women themselves might say they were being treated as such—arose out of their own expectations about the work appropriate to women. It was less an assessment of the work’s demanding nature than it was an unthinking assumption about who did what sort of work in a properly organized English plantation.

Both men and women in Plymouth understood their project as one of plantation. For them, plantation meant transplanting the society they knew as well as the household work regimens that made it possible. Plantation proposed making the outpost in New England into a place where they could live, work, and raise children. They looked at unoccupied land and pictured English farms, with fields and livestock. They balked when the pressures of the first year forced a departure from usual household practices. Their own ideas about how a society was organized were so deeply engrained that they interpreted Native society within the terms of their own familiar ways and judged it lacking. Despite an early period of adjustment—in which women complained that they were treated as slaves—they gradually succeeded in their project of transplantation.

The plantation of New England involved many facets, including the migration of English families and the recreation of English ways. Their goals and understanding of land use led the English arrivals to read American lands with English eyes. The idea of plantation contained a constellation of other ideas: expectations for how best to use the land, hopes for what such bounty would mean for their countrymen and women, and blindness to other ways of living on the land. Plantation, a goal dear to the settlers (or rather planters), shaped their project in Plymouth and beyond.