Kasslerrollen and Toast Hawaii: Post-war Indulgence, East and West, 1949 to 1990

After a twelve-year-long exercise in locavorism (even if it was sustained by unscrupulous plunderings from helpless victims), hunting and gathering for whatever was available while continuously being told what to eat, even what to crave, followed by some real hunger, Germans were ready to indulge. As the rubble was cleared, houses, towns and entire cities were rebuilt, traffic and industry got once again on track, and the economy was at last on the up, waistlines quickly expanded. But it wasn’t quite that simple. There was yet another layer waiting to add to the culinary complexities that had built up since the gruel of old, a giant experiment that would divide the Germans into two groups and subject them to contrasting political systems. How would they react? Would they develop equally contrasting cuisines? Would West Germans succumb to American-style consumerism and the lure of the brave new world, while their compatriots in the East filled their larders according to communist principles, adopting Russian recipes and drinking vodka?

The answer is that they did indeed move in opposite directions up to a point. But in many ways the differences that later emerged after reunification in 1990 were due to regional preferences and pecularities that went back much further. Yet the different political systems the two parts of Germany were part of had another effect. While West Germans were free to discover the Western world on their plates (either at home or through travelling), East Germans, with a few exceptions, were much more restricted in their choices and stayed closer to home in their cooking (and travel). The GDR wasn’t on a completely different food planet, but because of its economic problems got caught in a kind of time warp. West Germans would often comment upon the nostalgia they experienced during visits to the East, as food there seemed less industrialized and more homemade, the style of cooking more down to earth.

While the 1950s on both sides of the new internal German border were a period of rebuilding, rationing on the eastern side lasted significantly longer, until 1958. The Politburo was more than optimistic at that time, announcing that the GDR would surpass the FRG in food consumption levels by 1961. Officials were convinced that to expand local production and make the country independent from food imports, individual private farmers had to be completely eliminated and replaced by a centrally planned, state-run agriculture based on the Soviet model. In 1959 and 1960 Landwirtschaftliche Produktionsgenossenschaften (LPG), or agricultural collectives, were formed by force. Reactions among farmers ranged from resignation to emigration and suicide, making for a significant loss of specialist knowledge and motivation. In 1960 the combination of a failed crop with unsuccessful experiments in open stabling for cattle almost made for a crash in food production. As meat, bread and many other things became scarce, the populace reacted with panic buying and angrily threatened with riots and strikes.

This brought the communist experience to another level, with the regime ordering the complete closure of the border between East and West in August 1961. Following this, a certain economic and social stabilization set in. Cut off from the Western free market, an egalitarian ideal of stable prices and zero unemployment seemed tangible. By 1963 food supplies had gradually normalized. Choicer meat cuts and ham continued to be scarce, but basic foodstuffs were reliably available; nobody went hungry because of food shortages. Quite the opposite: generous portions became a way of life, with butter and pork in particular consumed in impressive quantities. A meal without meat was not taken seriously at all. Minced meat, Jagdwurst (a kind of scalded, smoked pork sausage) and Kasslerrolle, brined pork neck, were much-loved standards. Kalter Hund (cold dog), thin biscuits layered with a chocolate mixture rich in fat and sugar, was a cake favourite among children.

Unsurprisingly egalitarianism had its problems. Some citizens of the workers’ and farmers’ state were more equal than the rest and thus higher up in the food chain. The very small political elite group of the Politburo lived a very isolated and luxurious life. Their highly secluded and secured settlement a short drive north of Berlin, first in Pankow, then Wandlitz, had its own leisure facilities, hospital and bunkers and was amply provided for, with many goods imported from the West. As was to be expected, the lonely group at the top quickly lost touch with the real world beyond their small secluded realm and increasingly dismissed expert knowledge when taking decisions. They insisted on increasing crop production with vegetables completely unsuited to the areas in question, just as they were puzzled to find on a rare outing that sugar cube production didn’t cope with demand. Complaints about shortages were usually blamed on some local subordinate and often met with a simple reshuffling of distribution instead of basic reforms. But citizens’ Eingaben, petitions, could also lead to political actions at the highest level if the regime deemed the issue politically sensitive. Thus in 1977 shortages of coffee (which had to be imported against hard currency) led first to the introduction of Mischkaffee, a mixture of ersatz ingredients such as chicory, rye and other grains with a minimal addition of real beans. After more complaints, this time about the unpalatability of the ersatz coffee, the regime engaged in secret weapon trading to get hold of coffee beans from Ethiopia, Angola and other ‘new nations’ such as Vietnam, Laos and the Philippines. Eventually in 1978 Western coffee brands such as Tchibo and Jacobs were introduced in exclusive Delikat shops, albeit at horrendously high prices.1

Kasslerrolle, deboned brined pork: always available, forever popular. From the GDR cookbook Kochen (Leipzig, 1983). |

|

In fact since 1948 rationed goods had been offered, albeit at much higher prices than in regular shops, in state-owned Handelsorganisation (trade organization, HO) stores. This ‘state-run black market’ aimed to lure shoppers away from private shops as well as soaking up the monetary overhang – people had more money in their hands than available goods in the shops to spend it on. Officials praised the state-owned stores:

In the food stores of the state organization you’ll find all you need – from tropical fruit to smoked herrings. The simple people you’ll meet here are shopping in their own shop, just like you. The state’s own retailer offers you everything without anybody making a profit on it.2

When rationing was abolished in 1958 the HO group continued as a normal retailer and came to include restaurants, hotels and the large Centrum Warenhäuser department stores. In addition private restaurants were provided with the HO range of special foods and imported beverages. In the long term the HO group made a massive and continuing loss which weighed on the government budget. As costs for raw materials and energy rose over the years, state subsidies for food were huge due to the fixed prices officials didn’t dare to adjust, as they deemed holding them at the same levels vital to safeguard the precarious political balance. Instead they continued to offer scarce, highly desirable goods in special stores at much higher prices, opening the first Exquisit shops with fashionable clothes and shoes in summer 1961, followed in 1966 by Delikat, a new chain of luxury food shops. By the 1980s both Exquisit and Delikat had developed into a standard source of supplies for a large part of the population. Anything a bit more refined than the most basic goods could be found there, from wine, spirits, fish, cheese and chocolate (regular GDR quality containing as little as 7 per cent cocoa), to meat, sausages, special bread, export beer and much else, in packaging that was up to Western standards. Some of these special Delikat wares were even found in a section of regular stores in rural areas. At a certain point the Delikat stores’ success undermined general supplies. As demand exceeded supply, ordinary foodstuffs were elevated to Delikat ranks and normal shelves were stocked with lower quality produce. Meat in sausages was made to go further by the addition of potato starch, blood plasma, powdered skimmed milk or liquid egg, leading to complaints about their taste and extremely short shelf-life. The introduction of a supposedly superior Delikat butter in 1988 at almost triple the regular price caused much uproar. A pensioner wrote in:

Also, butter is now sold at Delikat, the 250 gram piece for 6.80 marks. What is this supposed to be? What is the butter we are eating for 2.40 marks? I mean, what is going on? Did we, who are pensioners today, build up our republic that badly and what did our hundreds and more of voluntary hours of work for which we only received coupons and not 5 marks, count for at all? Are the values we have created nothing?3

Delikat and Exquisit had been preceded by Intershop stores. First started in 1955 at the Baltic port of Rostock and aimed at the hard currency of seamen and travellers, Intershop stores proved so successful they were quickly extended to ferries, airports and large hotels, offering the usual array of spirits, cigarettes, sweets and coffee. They acquired an even more important status after the Berlin Wall’s construction in 1961, as they were installed along the transit routes between West Germany and West Berlin as well as at all checkpoints and in railway stations. From 1967 a select group of GDR citizens, such as diplomats and artists, were allowed to use them as well. From 1974 their selection was extended to food and they were officially opened to East Germans, as the government tried to get their hands on the population’s hard currency, whether received from friends and family or illegally traded. By 1976 as much as 85 per cent of the Intershop revenue came from GDR citizens. At the related chain of Interhotels (which were run according to the same principles) 80 per cent of all customers were East Germans.4

Food parcels from ‘the West’ were part of life for many East Germans, mostly, but by no means exclusively, at Christmas. At some points these private imports of chocolate, coffee, clothes and shoes surpassed the GDR’s own production.5 The grateful recipients in turn typically sent back Stollen. Paradoxically the rich Christmas cake associated with Dresden was made from almonds, raisins, candied peel and other commodities that were scarce and had to be imported against hard currency. It is in this context that the GDR Institute of Nutrition proudly announced in 1981 a newly developed method to candy (domestic) green tomatoes, with the result declared almost identical to standard citrus peel.6

Access to Western currency or special connections created a separate consumer class, corrupting socialist collectivism. In the late 1970s GDR citizens could be categorized like this: first and lowest were workers, pensioners and others with low income and no access to hard currency (and who therefore couldn’t buy coffee at Intershops); they were followed by citizens with an income high enough for Exquisit goods; who in turn were topped in this ranking by people who could get hold of West German currency and therefore were able to satisfy their needs at Intershops. Finally there were the very privileged, mostly high-up state functionaries who could buy at ‘special shops’ and drive expensive Western cars and who were not affected by any of the economic hiccups. Everybody in the GDR knew that this was how the system actually functioned. Nevertheless, in 1977 the ever-optimistic regime claimed that ‘of course, these [Inter]shops weren’t a permanent companion of socialism’.7

The GDR became nearly self-sufficient in basic foodstuffs, but above that consumer choice was often limited and quality patchy. Egalitarian ideals didn’t always translate into flexibility or good service, just as nationally defined goals were tricky to coordinate with individual production plans. Food distribution suffered from bad planning and lack of coordination as well as disinterested carelessness. Good quantities of fish would be caught on the Baltic but never made it inland due to the lack of refrigerated transport. Tomatoes, cherries and even precious imported grapefruit and peaches rotted because workers didn’t feel like doing overtime. Only red and white cabbage as well as apples were sturdy enough to be reliably available. HO stores and Konsum cooperatives had a bad reputation concerning cleanness, selection and presentation. Customer service was almost unheard of. Dissatisfaction was rife and in spite of contemporary nostalgia surrounding GDR food culture (which will be discussed in the next chapter), petitions in 1979, the East German state’s thirtieth anniversary, included many questions and complaints. Was it true that rationing coupons would be introduced for meat after the elections? Why were many high quality products either exported or sold only in Exquisit shops where normal people couldn’t afford them? What were the reasons for shortages in bed linen, cars and vegetables? Would the situation be even worse in the coming years with no elections and no state anniversary? In 1986 the GDR’s own market research institute found that 40 per cent of all food was of lower quality than in 1980.8 Propaganda slogans tried to transform the populace into politically and socially responsible consumers who would obediently buy what was on offer instead of clamouring for what wasn’t. Nevertheless a petition from 1987 stated: ‘Never has shopping caused so much worry and effort as lately.’ Perceived as a socialist shop window to the capitalist West, the GDR capital had absolute priority in everything, including food supplies. In popular opinion Berlin housewives went shopping, whereas in the rest of the republic they went out searching for food. Some East Berliners felt like Westerners, supplying their compatriots in the neglected provinces with scarce goods. Frequently people queued without even knowing what they were queuing for and then bought more than they needed to compensate for the effort. Even in expensive Delikat stores shop assistants often kept the most wanted goods under the counter for preferred customers as Bückwaren, or bending ware. Home production was widespread in the form of immensely popular Schrebergärten, allotments, with preserving and later freezing fruit and vegetables being common practice. Some of the produce from these private ventures was also bought by the state, which paid higher rates than the fixed shop prices, then sold the produce at a loss in the HO stores, demonstrating the absurdity of the economic system. Statistically living standards rose in the 1970s and ’80s. Increasingly households could afford TVS, refrigerators, washing machines and cars. However, waiting lists were long as the economic capacities of the GDR were over-stretched due to the building up of heavy industry (a declared priority) and maintaining its own sizeable army.

Kindergarten in Oberschweissbach, GDR, January 1980, during lunch. Note that the young woman is not eating with the children, but seems to be just supervising them.

The state desparately needed women in the workforce due to the demographic imbalance resulting from the Second World War, which was followed by the loss of an important number of young males to the West before August 1961. Occupation among women of working age rose from 66.5 per cent in 1964 to 82.6 per cent in 1976.9 Childcare was amply provided and a birthrate decline in the 1970s was countered with very generous maternity leave provisions. Collective feeding programmes in schools and factories were an essential part of East German socialism. This required a radical remaking of traditional German eating culture. Home cooking was reduced to simple evening meals (traditionally cold) and Sunday lunch. In 1978 almost every second GDR citizen ate his or her main weekday meal in a school or works canteen. The latter also provided workers with half-cooked meals, prepared vegetables and peeled potatoes to take home; factory shops were able to offer scarce goods such as condensed milk, pork fillet, strawberries and higher quality beer. With the state producing seven million dinners daily, this could have been the opportunity to positively change people’s food habits, but once again official theory and the reality on plates massively diverged; on the one hand there were campaigns for healthier nutrition patterns, and on the other the lack of any initiative to instigate them in communal meals.10

Although in the 1970s (in contrast to West Germany) GDR women were proud of being able to do men’s work, they soon noticed that in spite of all propaganda they still lived in an unequal, gender-divided society that expected them to carry a double burden. Role models of old regarding household chores, hierarchies in the workplace and women’s representation in political and social committees didn’t change significantly, since society’s understanding of men’s role remained unchanged. In 1970 a study found that of the weekly 47.1 hours on average spent on housework per household, women did 37.1 hours, men did 6.1 hours and ‘others’ (mostly grandmothers) did 3.9 hours. The state-run HO restaurant chain in 1960 advertised its catering services for Jugendweihe day (the youth initiation ceremony for fourteen-year-olds that had replaced Christian rituals and took place on a Sunday in late spring) by promising working mothers ‘a day which many families will have discussed and saved for during the whole preceeding year’, with ‘the advantage that mother and grandmother can celebrate like everybody else’. Warm and cold dishes, even entire meals including plates and cutlery, could be ordered from the central HO kitchen. It is difficult to know how many families actually had a chef come and prepare mushroom soup, tongue in red wine with vegetables and potato balls and then lemon cream as dessert, bringing all the necessary pots and pans along and taking away the dirty plates with him after the meal.11

By no means all official planning was doomed. Goldbroiler, a chain of diners selling grilled chicken, was a huge success. The idea was born in 1964 when the Soviet Union threatened to reduce food deliveries. The East German regime, ever scared of political destabilization, sought to close the ‘meat gap’ with domestic production. To achieve this they were prepared to import Western technology. From 1965 a special committee was put in charge of building up modern industrial poultry production and thus set an example for the further development of GDR agriculture. Dutch, West German and British technology was imported via Yugoslavia, and from 1966 set up in state-owned Kombinate für Industrielle Mast, industrial feeding combines. Even with the exceptional empowerment granted directly by the party leaders, Goldbroiler was financially precarious. But the project persevered, mostly due to its perceived political importance, and eventually those in charge could admit to the politically delicate fact that their model had been the hugely succesful German diner chain Wienerwald (founded in 1955 and selling grilled chicken). When the first Goldbroiler restaurants opened in late 1967, the broiling equipment still needed to be imported from the ‘capitalist enemy’. Partly because poultry at the time was regarded as a luxury, partly because these restaurants were true family places, they proved to be an immense success that put the chicken-producing Kombinate under enormous pressure to meet the demand.12

The name Goldbroiler seems ironic, as GDR language politics in many ways resembled those of 1870s Germany. But in officials’ books, conveniently ignoring its American origin, Broiler had been adopted from the Bulgarian industry as a special meat-rich chicken breed. Most streetfood was linguistically nationalized to detract attention from its Western capitalist origins. Hot dogs, served in special buns with cucumber ketchup, were rechristened Ketwurst. Krusta, a square version of pizza with a darker, rye-bread-like dough was introduced in the early 1980s. It came with all kinds of toppings ranging from the exotic Black Sea to the homely Spreewald. Hamburgers were called Grilletta and consisted of a pork burger sandwiched in a crusty bun with the addition of sweet and sour chutney, although some remember it as gratinated with cheese and vegetables. All this upmarket fast food was initially and mostly directed at the crowds on Berlin Alexanderplatz, one more of the capital’s many privileges.

A culinary place in time: the Konnopke sausage stall in Berlin-Prenzlauerberg

Max Konnopke was born a farmer’s son in Cottbus in 1901 and moved to Berlin in the late 1920s. After working as a day labourer on construction sites, in 1930 he and his wife tried their luck as Wurstmaxe, venturing out each night (as daytime sales were heavily regulated) with their Wurstkessel, a metal pot containing different kinds of sausages in hot water, on a folding table protected by an umbrella. Nightlife in the Prenzlauer Berg district was good for business. When meat became scarce at the end of the 1930s, they sold Kartoffelpuffer, potato pancakes. In 1947 they moved into two wooden sheds, which were soon replaced by mobile carts. Later their son-in-law joined the company, expanding it to various weekly open-air markets and the Christmas market. When their son trained with a West Berlin butcher in 1960 he discovered Currywurst, as yet unknown in the East – at least that’s how the Konnopke website tells the story. The Konnopkes, always quick at spotting an opportunity, created their own version of tomato ketchup and the new dish became extremely popular with factory workers, craftsmen, nightowls and other Konnopke aficionados, sometimes being referred to as an Indian dish. Max worked until 1976, passing the business on to his daughter Waltraud, who built a new kiosk in 1983. Today the kiosk, situated next to the Eberswalder Strasse subway station, is run by Waltraud’s son Mario and his wife. With the fall of the Wall, the urban landscape gradually changed. Students and tourists replaced the workers and opening times are now ten to eight, with Sunday closed. Konnopke has become a cult, but the sausage is still skinless, and said to be an East Berlin speciality (www.konnopke-imbiss.de).

Almost simultaneously with Goldbroiler, another successful restaurant chain started. This one was based on fish and called Gastmahl des Meeres, banquet of the sea. At the time fish was rather plentiful due to the large GDR fishing fleet. The idea came from Rudolf Kroboth, responsible for sales at the VVB Hochseefischerei, the combineed deep-sea fishing cooperative in Rostock on the Baltic. The first Gastmahl des Meeres opened in Weimar in 1966 and was quickly followed by fifteen others all over the country. The menu and design (in blue and white) were the same in all outlets, said to have been based on American family restaurants. Like these the restaurants were advertised in magazines and in cinemas, but also through Kroboth’s own TV cooking show, Der Tip des Fischkochs (The Fish Chef’s Tip), every week from 1961 to 1972. The self-trained Kroboth regularly summoned his head chefs to Rostock for training sessions. The Gastmahl des Meeres menu offered up to 100 different dishes, mostly simple, solid fare such as potato salad with baked fish or fried herring with boiled potatoes. Although herring, pollock and cod featured most prominently, customers could also indulge in Russian keta caviar.

Food magazines or critical restaurant guides as such didn’t exist in the GDR, but many newspapers and magazines ran a section with recipes and nutritional advice. One of those was Liebe, Phantasie und Kochkunst (Love, Fantasy and the Art of Cooking) by the agricultural writer and journalist Ursula Winnington, printed in the popular monthly Das Magazin. She combed literary sources for foreign dishes such as asparagi alla milanese, Chicken gangbao or Imam bayildi, Turkish stuffed aubergine, but was also allowed to travel internationally and collected recipes on those occasions.13 In its 1983 edition the West German restaurant guide vif Restaurantführer included GDR restaurants. A West German food critic had been taken to 55 restaurants and hotels on two state-organized trips. Although he liked and recommended some places, above all the Müggelsee-Perle, a tourist destination in the south of Berlin, GDR authorities didn’t appreciate his efforts and confiscated the specimen copies the Hamburg publisher sent to the featured chefs. An article about the guide in the West German magazine Der Spiegel from November 1982 made clear what the reasons for this might have been:

Only British gastronomy has an even worse reputation than the German democratic one. Long waiting times, seating regulations, rude service, meagre offerings, ‘hunting meals’ at which plates are grabbed from eaters as soon as they put down the fork – all this is part of GDR everyday life.14

The restaurant guide pronounced regional food such as Lausitzer Hochrippe (Lausitz rib roast) and Thüringer Klösse (Thuringian potato dumplings) best, but admitted that it wasn’t exactly lean cuisine. The GDR publication Gastronomische Entdeckungen (Gastronomic Discoveries, 1984), could be seen as a reply to this West German impudence. It presented restaurants and regional specialities from all over East Germany. Pork and sausages featured prominently. The author Manfred Otto, quoting a GDR survey on Thuringia, said that over a third of East Germans associated the region around Weimar and Erfurt with Thüringer Klösse, the famous dumplings made mostly from raw potatoes and stuffed with croutons, while the rest thought of Thüringer Rostbratwurst, bratwurst. He declared Thuringians to be real foodies, loving anything good and porky, but also the wild watercress that grew (and still grows) along streams and rivers between Erfurt and Eisenach.15

East Germany’s 26,000 restaurants were categorized in five official price groups, with over 70 per cent belonging to the two lowest ones – which also meant they were the lowest in the supply chain. In many personal recollections East German gastronomy is described as limited and unpredictable, with only Soljanka and Letscho available with some reliability. Soljanka originated as a Russian or Ukrainian soup made with pickled mushrooms, cucumbers or vegetables, tomato, lemon and sour cream; Hungarian Letscho is a spicy dish of bell peppers, tomato and onions, somewhat in the style of an Italian peperonata. East German restaurant offerings mostly represented very liberal variations on those originals, based on supplies. Würzfleisch, a kind of ragout, was another stalwart at gastronomic outlets. Waiters are often remembered as surly at best, rude at worst. Seating regulations in restaurants (unheard of in West Germany at the time) forced people to queue in spite of empty tables, as the staff were generally slow in clearing tables and often refused to serve outdoors as it was too much bother. True to socialist ideals of equality, nobody expected any form of service from anybody else.

But there were exceptions, in particular among privately owned and run restaurants. Although many of the remaining private craftsmen and small companies had been forced to sell out to the state in 1972 (following a pattern somewhat reminiscent of Jewish dispossessions in the 1930s), private shopkeepers and restaurants later came to be quietly encouraged, as they proved more efficient than the state-run establishments. In 1989 they accounted for 43 per cent of all restaurants.16 Ambitious chefs included Doris Burneleit at the Italian-themed restaurant Fiorello, which she opened 1987 in Berlin, and Rolf Anschütz (self-taught, like Burneleit), who from 1966 gradually transformed the Waffenschmied (Armourer) in Suhl/Thuringia into an extremely traditional Japanese restaurant complete with naked bathing rituals, kimonos, chopsticks and sake. Both Burneleit and Anschütz had to study their chosen foreign cuisine in whatever literature they could find and make do with what they could get their hands on in the kitchen. Frequently improvisation was needed – Burneleit marinated Edam cheese in white wine and dried it in a well-aired chimney to stand in for the unobtainable parmeggiano. Anschütz was lucky: Japanese guests were so impressed that they supplied him with original ingredients by post. In 2011 his story was made into a film, Sushi in Suhl. The Konnopke family with their sausage stall in East Berlin’s students’ and artists’ district Prenzlauer Berg was more pragmatic: they temporarily switched to fish when meat was scarce in the early 1960s. At the ambitious Hotel Neptun in Warnemünde it helped that the director could offer holiday stays when bartering for food. The five ethnic restaurants opened in 1978 were said to be the most expensive venues in all East Germany. They featured Cuban, Hungarian, Russian and Scandinavian cuisine as well as local seafood. The Neptun, like other high-end hotels built by a Swedish company, opened in 1971 and was based on the highest international standards. Offering 757 beds, the hotel was fully booked until the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989. It was unusual in that it eventually welcomed both East Germans (80 per cent) paying with their own currency, and international guests (20 per cent), who had to exchange their respective currency into ‘hotel money’ to level out black market rates.17

By 1965 holiday trips were high on many East Germans’ wish lists, but most people necessarily stayed within their own country’s borders. Against widespread perception, travelling was not all state-organized, but long waiting lists were the norm, particularly for trips to neighbouring socialist countries. Young people often risked hitchhiking and camping was very popular. Travelling seemed much more easy in cookbooks. Kochen, together with its sister publication Wir kochen gut the most important East German cookbook, in its sixth edition of 1983 dedicated a chapter to international dishes based on holiday trips. Bulgarian Tarator (a cold cucumber soup), Czech Kuttelflecksuppe (tripe soup), Hungarian Palatschinken (pancakes), Caucasian Plow (pilaf), Polish Gurkensuppe (cucumber soup) and Roumanian Mititei (grilled ground meat rolls) were all lovingly mentioned in the introductory text. The recipes that followed were mostly from Russia and Central and Eastern Europe, but also included some French classics such as rillettes, onion soup and bouillabaisse, an Indian pumpkin stew and minestra (made with potatoes and spaghetti). A special section with the title ‘Foreign specialities for curious minds’ started with Süsssaures Schweinefleisch, sweet and sour pork, and Szegedin goulash followed by Burgunder Bohnen (green beans with carrots, bacon and unspecified red wine), Bami, paella (with pork and fish), stuffed vine leaves, short ribs braised with white cabbage and apples, beef fillet in puff pastry, ravioli, Pelmeni and Honigbroiler (whole fried chicken glazed with honey, mustard and curry powder) as well as apple pie, Russian carp (served on sauerkraut) and Fisch mit Gemüse, fish with vegetables – a mix of international classics, imagined exotica and perfectly normal fare. As was the case in West German recipes of the time, exotic ingredients were replaced by what was locally produced and available, such as domestic Erwa or Bino food seasoning, which stood in for soy sauce. However, to include eight recipes involving bananas, which were exceptionally rare, seems to border on the sadistic.

Italian cuisine’s appeal didn’t stop at the inner German border: pizza and spaghetti. From the popular GDR cookbook Kochen (Leipzig, 1983). |

Some of those dishes were also presented by East German TV chef Kurt Drummer in the fortnightly half-hour series Der Fernsehkoch empfiehlt (The TV Chef Recommends). Unlike his colleague Rudolf Kroboth, Drummer was a professional who commandeered the stoves at a number of large Interhotel kitchens. His tasks on TV seem to have included directing consumers towards available foodstuffs, and he adjusted his cooking presentations accordingly. However, without a hint of irony, the cookbooks that went with the series featured Italy and Austria next to Cuba and the Soviet Union.18

Particularly during the 1980s, culinary inspiration beyond sauerkraut and potato salad could have been gathered closer to home. Although the GDR was perceived as a monocultural state, refugees and students workers from fellow socialist countries provided foreign influences. From 1987 Vietnamese represented the single largest foreign ethnic group among them. The regime had declared its solidarity with the fellow socialists who urgently needed economic help after the Vietnam war and the following socio-economic crises. Investing in local pepper and coffee production, East German officials in return saw a chance to deal with their own lack of labour, mostly due to inefficiencies in their centralized planning. In theory foreign workers were extremely segregated in every aspect of life. Although the reality turned out to be both more lax and more severe, depending on the circumstances, their culinary influence nevertheless seems to have been minimal. Sources on GDR contract workers, for instance, never mention factory canteens offering special meals. The populace had not been told that each contract worker helped to reduce the state deficit; they only saw that authorities had not planned for the Vietnamese workers buying rice, pork, sugar and poultry and thus blamed them for even more patchy supplies on the shelves.19

GDR versions of Worcestershire sauce and ketchup, from Kochen (Leipzig, 1983). |

|

On the evening of the GDR’s fortieth anniversary on 7 October 1989, the Politburo members dined in style with international state guests, among them the Romanian Ceausescu, the Palestinian Arafat and the Soviet Gorbachev, at the Palast der Republik, the Republic’s Palace. Built on the site of the demolished imperial Schloss and opened in 1976, this was the GDR’s most ambitious and expensive building project. Behind bronze-coloured reflective glass, it housed not only the parliament, but also two large concert halls, a theatre, art galleries, a bowling alley and a discotheque. Needless to say, the thirteen restaurants also to be found under its flat white roof never experienced any supply problems. They specialized in theatrical performances such as flambéing and preparing steak tartare at the table. That evening the menu was conceived to impress: quail breasts were served with creamed corn as a starter; then came trout rolls with dill sauce and trout caviar, followed by turkey soup with pistachio dumplings and tomato royale, all accompanied by domestic Rotkäppchen sparkling wine. Filet-Ensemble Trianon followed as main course, composed of veal fillet with ham duxelles, beef fillet with a vegetable bouquet and chicken medaillons with half a peach. Dessert was an ice cream creation on a chocolate-marzipan sponge cake, appropriately named Surprise. By then a 3,000-strong crowd of mainly young protesters had marched over from nearby Alexanderplatz where a celebratory fair with dance music had been held, chanting Freiheit and Wir sind das Volk – freedom, we are the people. Just five weeks later the Berlin Wall fell and West Berliners would welcome their former and future compatriots with sparkling wine and bananas.

Window of Café Central in Leipzig on the occasion of the SED party convention, 1987.

The 1950s in West Germany have often been labelled as Fresswelle, or wave of gluttony, but at closer inspection this turns out to be an oversimplification. Admittedly eating one’s fill for many was a top priority immediately after post-war hunger. A woman remembered April 1949, after the Deutschmark had been introduced:

Suddenly in the shops there were such mountains of butter, eggs aplenty, those milk shops, you could buy cream, liquid cream. And white flour, white flour, oh, that was so nice. And then the fat on top and a bit of coffee, real beans.20

Following the founding of the FRG in May 1949, West Germany quickly adopted a free-market economy and deregulated food prices, although they were indirectly influenced by the state regulation of the agrarian market (later on the EU level), protecting German farmers. Buyers valued the quickly growing freedom of choice, furthered by the introduction and rapid success of self-service stores and supermarkets. At first they were few and far between: just 39 in 1951 in all of West Germany. However the American food industry was keen to change this in order to conquer the German market (on a political level, the resulting higher living standards were also thought of as an essential way of fighting the communist threat). In 1953 an American exhibition on the subject toured through Germany, but the turning point came at the ANUGA food show in Cologne in 1957, where a special exhibit with almost 40 modern self-service shops was displayed. From then on, numbers as well as turnover quickly rose: from 326 stores in 1955 to 53,125 in 1965. Their share in turnover of the retail market for food went up from 4.4 per cent in 1956 to 34.8 per cent in 1960 and 62 per cent in 1964. As the investments necessary to remodel existing shops were substantial, independent shops tended to form chains, such as Spar, founded in 1953, and in the long term the number of independent bakers and butchers declined substantially.21

Until then everything had been weighed individually in front of the buyer, often into their personal receptacles such as bowls or bottles, which could easily take twenty to 30 minutes. Now food needed to be uniformly prepacked instead of being delivered in large sacks or bags, barrels or boxes. People commented that they missed the small talk of the old shops, but they also valued the time saving and being able to choose freely and at leisure. Generic food items were gradually replaced by brand names, with a rising number of options available. New foodstuffs such as margarine, chocolate, cocoa powder, condensed milk and baking powder were the pioneers. Brands provided printed guidance, replaced the verbal sales talk of old, and promised reliable quality. For these reasons packaging played an essential role, with new synthetic materials such as cellophane on the rise and gold the most successful colour. Industrial convenience food such as Puddingpulver, custard powder, Maggi soup seasoning, packet soup and tinned ravioli (the latter introduced in 1957) were or became increasingly popular.

The currency reform of 1948 marked the end of the standardized ‘regular consumer’ and the 1950s were more about diversification than just gluttony. Even working-class families with restricted budgets longed for something special and refined. Thrift was still considered essential, and housewives continued to be admonished to act responsibly and save. Invariably seen as naturally suited to the job, they were portrayed as responsible for their family’s happiness, farmers’ success, avoiding shortages or otherwise hampering a prospering economy (by shopping for domestic produce according to seasons), the integration of refugees and much else. Initially consumption for most was still limited, but not monotonous: for instance, Christmas and Easter were marked by special meals including meat and sweets, as were Sundays, with white rolls for breakfast and chocolate pudding for dessert. The often quoted waves (as the Fresswelle was supposedly followed by a general emphasis on house and home, then on travel and finally on health as top priority) might have their origin in individual experience, as people remembered being gradually able to afford more: first a Sunday roast, then wine in the evening, then a refrigerator, then a short holiday trip in summer. While slowly catching up with American consumers, the delicacies people had been dreaming of weren’t taken for granted, since they remembered the first this and the first that very clearly as something special, such as the first roast goose for Christmas. Slowly expenditures on food went up, but with wages rising as well, they came to represent an ever smaller proportion of disposable income: an average of 46.4 per cent in 1950 decreased to 36.2 per cent in 1960. A worker needed to work for about four hours to buy 1 kg of butter in 1950 (as compared to about one hour for workers in the U.S.), down to about two hours in 1960 and one hour in 1970.22

For most West Germans in the 1950s meat was special and far from affordable every day. Between 1950 and 1960 annual consumption of pork per head rose by 50 per cent while that of poultry tripled, especially because prices for the latter went down from the mid-1950s on due to industrial production. Much less non-white bread was eaten, but rye bread remained dominant, at least in working-class households: a four-person household in 1950 consumed on average 23.2 kg of non-white bread per month and a little under 5 kg white bread. The last figure stayed more or less constant up to the early 1960s, whereas the former declined steadily to 14.9 kg.23

Until the mid-1950s, in rural areas, grain was still sent to the miller who in turn gave the flour to the baker who then made one’s bread for a fee, and also baked large sheet cakes prepared at home. But the general tendency was to bake less at home and buy at the baker’s instead: the amount of flour purchased went down by half whereas expenditure on baked goods doubled. This included Teilchen, small Danish pastries, during the week, marking the start of a less strict differentiation between Sunday and weekdays. However housewives still had to demonstrate their skills. Obsttorte, a baked base covered with fresh, tinned or steamed fruit and a glaze, became a favourite. It was easy and quick to make and was considered tasty and healthy. The Dr Oetker company, a leading producer of baking powder, compensated for losses in sales by launching a similarly packaged powdered jelly glaze in 1950. It was an instant hit.24

West Germany developed into an important import market for fresh fruit and vegetables. Allotment gardens lost some of their importance in daily food supplies as transport became ever better at dealing with delicate and perishable foodstuffs. Women still preserved fruit and vegetables, but younger generations were less likely to do so, and then mostly only to save money. Over 80 per cent of imported vegetables (with the Netherlands the dominant source) were of just five varieties: tomatoes (which shot up in popularity as they filled a seasonal gap and were deemed very decorative), cauliflowers, onions, cucumbers and lettuces. At the same time the consumption of potatoes went down, as did that of legumes. Especially in urban areas potatoes were increasingly consumed in the form of convenience food, such as dried potatoes used for dumplings or frozen chips. Rice was gradually accepted as an alternative, with parboiled boil-in-the-bag rice first offered in the late 1950s. From 1958 significantly more fresh fruit was eaten: mostly Südfrüchte (citrus and tropical fruit) besides the traditional apples and pears. When tinned fruit and vegetables became more widely affordable in the mid-1950s, they quickly became very popular. Tinned vegetables were considered handy, tasty and time-saving (with peas, peas and carrots and green beans top of the list), whereas tinned fruit was thought of as something special for dessert on Sundays or for guests, with pineapple a favourite through all social strata.

Margarine remained the dominant fat consumed in working-class households, but from the mid-1950s its consumption (as well as other vegetable fats, suet and in particular lard) went down in favour of butter. The consumption of full-fat cheese shot up, with Schmelzkäse, spreadable processed cheese, a favourite. Interestingly quark consumption also rose considerably, almost tripling. With the ban on cream officially lifted in 1952, consumption of fresh liquid cream went up but stayed at somewhat moderate levels, while condensed milk in tins became immensely popular.

For many real coffee remained a special treat, and only overtook ersatz products in volume in 1955. Total expenditures on so-called Genussmittel, luxury goods, including coffee, tea, wine, beer, spirits and tobacco, rose both in percentage and in absolute quantities, but tobacco and cigarettes moved down the ranks and were replaced by beer and spirits. Above all beer consumption shot up, most of it bottled and consumed at home. A similar urge to catch up resulted in chocolate consumption quadrupling, with the favourite flavours being (in decreasing order) milk chocolate, milk and nuts, coffee and cream.25

The Frankfurter Küche, the modern fitted kitchen, made a return in the 1950s and ’60s in a modernized and more adaptable form that came from the U.S. and Sweden and was integrated in the many new housing projects. Praktisch, sauber und pflegeleicht, practical, clean and easy-care, was the slogan of the time, with modern materials such as Formica popular, as were wipeable plastic table covers somewhat later. With fitted kitchens came electrical appliances, trickling down from higher to lower income households. A Küchenmaschine, or food processor, became an essential wedding gift. The hand-held electric mixer was used much more frequently, however, as the time needed to assemble and clean the food processor was deemed too great for smaller tasks. Modern kitchen machinery not only saved muscle power but changed the status of certain preparations; lengthy beating and whipping now didn’t take one’s own energy or that of a servant, but could be done at the flip of a switch. Refrigerators were at the top of most people’s wish lists (followed by vacuum cleaners and washing machines), but they were expensive. According to a survey, only 10 per cent of all households owned one in 1955, but almost every second household wanted one, and by the early 1960s they had one. This meant that women no longer needed to go shopping several times a day and could buy larger quantities at lower prices. Most insisted on a freezer compartment, often thinking that they would make their own ice cream. In fact they used it to store bought-in ice cream as well as frozen food. Frozen food started to appear in 1955, with an official presentation at the ANUGA food fair that year in Cologne. Once stores and private kitchens were equipped for it, consumption rose quickly, from 150 g per person and year in 1956 to 400 g in 1959 and 2.7 kg in 1963. Fischstäbchen or fish fingers, introduced in the early 1960s, proved to be a long-term success.

Housewives didn’t necessarily gain personal leisure time through all this modern technology, as expectations also changed: laundry was easier and more quickly done now, so everybody wanted a clean set of clothes more frequently than before. Many of these tasks had been previously outsourced and now returned onto women’s to-do lists. Whenever possible a warm midday meal was expected to appear on the table. On Sundays and special holidays these had to be extravagant, often including a soup and dessert. In 1949 Edeka (the oldest German food retailers’ cooperative, founded in 1898) started to publish a widely distributed free customer magazine with the title Die Kluge Hausfrau (The Clever Housewife), first fortnightly, then weekly.26 Initially the recipes included were still modest, with meat and fat making rare appearances and shortages frequently mentioned. In summer 1950 the lunch suggestions were the following:

MONDAY: cauliflower soup with star-shaped noodles, buckwheat porridge with fruit juice

TUESDAY: stuffed Savoy cabbage with boiled potatoes, cherry soup with semolina cooked in milk

WEDNESDAY: fried mushroom dumplings with Béchamel potatoes, lettuce

THURSDAY: broad beans and roots, diced bacon and mashed potatoes

FRIDAY: steamed mackerel in caper sauce, boiled potatoes, sugared berries

SATURDAY: sour aspic with mashed potatoes, Rote Grütze (a red berry dessert) with milk

SUNDAY: clear soup served in cups, kidney and heart ragout in a rice ring, an assortment of vegetables, apricot dessert.

With modern technology came new tasks for housewives which had been previously outsourced. The Piccolo of the 1950s shreds and mixes, but can also vacuum, polish or spray-paint.

Already for Christmas 1950 butter was taken for granted as an ingredient in Christmas baking, as were roast goose and veal. For New Year’s Eve a cold buffet was suggested and its logistics (clearing your husband’s desk and covering it with a large white cloth) explained in detail. It was a harbinger of things to come: all the dishes were to be elaborately garnished in bright colours using tomatoes, parsley and lettuce. Everything was to be easy and quick to prepare, so that the housewife had time to apply make-up and look fresh and just as decorative as the food.

An Italian salad for the New Year’s Eve buffet of 1950 announced a new internationalism. The culinary horizon was widening, at least in recipes’ titles. The phrase Mailänder Art, or alla milanese, was to be used frequently for pork fillet, veal, sausages and asparagus, mostly indicating the use of tomato puree and grated cheese (which from 1958 was Parmesan, parmeggiano, instead of the more general term Reibekäse). For Easter 1951 mock turtle soup made a comeback and Weincreme, wine cream, added a posh note by using the French spelling. On the same occasion Huhn auf französische Art (chicken the French way) was combined with Risipisi, the Frenchness of the chicken being guaranteed by the use of cognac. The small tin of green peas (still expensive and considered very modern) added to boiled rice for Risipisi further marked the special occasion. During the following years Frenchness signified various combinations of cognac, garlic or red wine (French cuisine as such was deemed ambitious and only became truly popular in the 1960s).

Clever housewives first heard of China in 1953 with an extremely freely adapted version of (Indonesian) nasi goreng and then again in 1961 with a number of sweet and sour recipes. In 1955 Toast Hawaii made its first appearance in the magazine, the same year the first West German TV chef, Clemens Wilmenrod, is said to have invented the gratinated concoction of boiled ham, tinned pineapple, cheese and a dollop of tomato puree, all on white bread. It was symptomatic of the pseudo-international cooking style that would soon reign. In 1958 Die Kluge Hausfrau invited her readers on a culinary world tour: Italy was represented with cod alla milanese, Portugal had a spinach roulade and France a Parisian omelette, while Dutch cooking was represented by a brain soup and Africa (as one entity) a banana salad. If nothing else, this last dish makes clear how arbitrary these recipes were, being much more concerned with preconceptions than authenticity. As the internationalization of recipes in Die Kluge Hausfrau progressed, regional German dishes came to be categorized as Hausmacherart, home cooking.

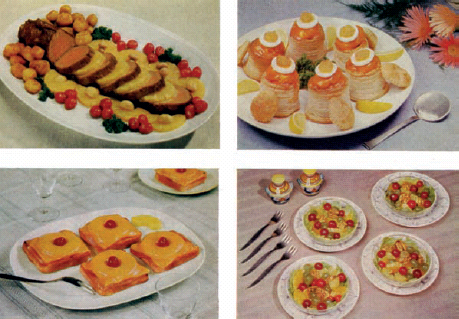

Toast Hawaii and other dishes for parties from the early 1960s.

Working hours gradually decreased, and as more families could afford their own cars, holidays became immensely fashionable. In 1969, 25 million West Germans took a summer holiday trip, and over half of them went abroad.27 This brought German tourists to Italian beaches, creating a lasting demand for wurstel con kraut along the Italian coastline and eventually leading to a renewed popularity of Italian food in Germany that is still pervasive. Since the end of the nineteenth century, Italian ice-cream makers, mainly from the region of the Dolomites, had been a feature of all major cities in the summer months, but during the 1950s and ’60s many of them moved to Germany for good. To this day many ice cream parlours are in Italian hands and known as Dolomiti. The first German pizzeria, Sabbie di Capri, opened in 1952 in Würzburg. It was run by an Italian from the Abbruzze region who had worked for the U.S. Army in Nuremberg. He found that American soldiers loved the food he was familiar with as poor people’s fare from his homeland, and soon his clientele expanded to include locals.

During the 1950s it was common to ask one’s friends around for an evening of drinks and snacks accompanied by music, singing and dancing. Punch and bowle were very popular, and from the mid-1950s so were whisky and brandy. Kaltes Büffet, a cold buffet, could include herring in cream, sardines in oil, tuna in oil, anchovies and a platter with cured ham, boiled ham and finely sliced Italian salami. Die Kluge Hausfrau boldly suggested serving a whole slab of Gorgonzola on a wooden plate, with a bowl of butter shaped in balls and a large basket with sliced white bread, black bread, crisp bread and Pumpernickel. For dessert seasonal stewed fruit and fresh fruit were recommended, with cheese biscuits, cheese with quark or ham and banana rolls to be offered during card games.

The word Party became a very trendy Anglicism, and with the introduction of the Partykeller (party cellar), the basements of people’s houses were finally converted from dark shelters to the brighter side of life. TV changed the way people spent their evenings as well as what they ate. The very first private TV sets in West Germany were introduced in 1952. Twelve years later more than half of all households had at least one (and almost 100 per cent in 1980). Cinema almost immediately started to decline in popularity as people drank and ate in front of the small screen. In particular men seemed to appreciate long evenings with plenty of good food in the form of Fernsehhäppchen (literally TV bites) and Schnittchen (small open sandwiches). Knabbereien such as saltsticks, crisps, roasted peanuts and the like became immensely popular, with the first crisps produced in Germany for the German market in 1959. The first TV food advertising in 1957 was for sparkling wine, chocolate, coffee and wine.28 Clemens Wilmenrod, the first West German TV chef, was a trained actor. His bimonthly (later monthly) ten- to fifteen-minute shows were shown live from 1953 to 1964. In these he conjured up a full meal without any restraints on the use of convenience products, letting his fantasy run free in terms of names and connotations. Producers of food as well as appliances soon noticed how efficient it was to be mentioned by the talkative entertainer. Freely embracing brands, he became entangled in serious arguments with the TV stations on the subject of plugs and product placement.29

Towards the end of the 1950s, recipes in cookbooks and magazines became increasingly complicated, even overblown. Instead of straightforward buttered bread with cold cuts, suggestions for the cold evening meal recommended bananas with ham on a bread plinth or tomato aspic. Schnittchen were garnished ever more lavishly and recipes’ titles frequently included the words Schlemmer, Lukull, Delikatess or Gourmet – now West Germans were seriously indulging. Bunte Platten, lavishly garnished arrangements, consisted of everything imaginable from red-capped ‘mushrooms’ made of hard-boiled eggs, half a tomato and dots of mayonnaise to a fleet of halved and hollowed pickled cucumber ‘boats’ filled with a meat salad and garnished with an onion ‘sail’ on a toothpick.

In the 1960s an opposing trend set in, with health-conscious recommendations and the appeal to stay slim or lose weight. Sugar, fat and overcooking were presented as the antithesis to natural health and slimness. As early as 1950 a magazine article had advised on how to stay slim:

Together with that whipped cream and those ham rolls, the chocolate and the smoked eel the worries about one’s figure have reappeared. Worries – of course that’s something quite different than these sighs caused by the good life, pangs of conscience about having overdone it out of joy about the reappearance of good things. But still: the coat is too tight, the jacket won’t close . . . and Herr Müller has to ask his small son if his shoes are dusty as his belly blocks the view. One thing is for sure: We’ve been eating too much lately, or rather been eating the wrong way . . . To get slim and stay slim, a sensible way of life with a sensibly mixed diet is needed. That means we prefer vegetarian to meat-eating, eating vegetables (prepared without flour and preferably eaten raw), salads (without oil and bacon, but with a lot of herbs), fruit and fruit juices. We avoid fatty meat and meat fried in fat, baked fish or fat fish such as eel, and for a while heroically say goodbye to sweet pastries, Torten, chocolate and other sweets. Quark and milk, boiled fish and boiled eggs enrich our menu. Instead of beer we rather drink a glass of Mosel wine and above all, as a general rule, we never drink during the meal, but only before or after and never too much.30

Officials had already taken action: in the early 1950s a West German government delegation went on a trip to the U.S. to study nutrition. In their subsequent publication they recommended higher consumption levels of fresh milk and fresh fruit, as well as fruit juice, and pleaded for nutritional education at all levels. Nutritional advisers needed to link up with science and the food analyses of old had to be reexamined. But the commission also pointed out that any reforms in Germany would have to come from private organizations, due to the fact that the populace was tired of being told what to eat by officials. In 1953 the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Ernährung (German Nutrition Association), was therefore founded.31

Meat producers took note and delivered meat with less fat from younger animals. Pigs in particular had to shed fat through revised breeding and feeding programmes. For beef, young bulls came to be preferred, with oxen and their marbled meat almost disappearing. At the same time meat became more affordable: in 1950 a worker needed to work for over three hours (198 minutes) on average to buy 1 kg of pork chops, whereas by 1984 this had reduced to less than one hour (58.7 minutes). The quality of the meat, however, often reduced with the fat, and West Germans continued to eat more than they needed as hard physical work tended to be replaced by sedentary office jobs. In 1981, 3,500 calories were consumed per person on average per day, and fat intake had tripled since the early 1950s.32

In 1958 Lufthansa introduced its ‘Senator’ first class service. A chef steward looked after passengers’ culinary needs.

As in earlier decades, housewives were often presented as the culprits. A study of ‘inappropriate nutritional behaviour in times of affluence’ published in 1979 accused them of feeding their families too much and at inappropriate times, regularly neglecting breakfast and putting too much emphasis on midday meals. Meal plans were pronounced to be ‘remarkably monotonous’. Soups were accused of furthering obesity and too little healthy fish, fresh and raw vegetables were eaten, although the latter had largely replaced legumes, deemed indigestible. Obesity was declared the most imminent threat, with every fifth child in West Germany suffering from it – again, mostly mothers’ fault. It is striking that neither anorexia nervosa nor bulimia nervosa were even mentioned at this point.33

It is worth noting that the study openly recommended convenience food. Freezers and frozen food had arrived for good in German households, of which more than half in 1978 had a freezer or freezing compartment. Fish fingers were followed in 1970 by the first frozen pizza produced in Germany; it was a huge success. That year the average West German consumed 10 kg of frozen goods on top of ice cream, a number that was to quadruple during the following four decades. Modern convenience food had started with canned ravioli and the immensely popular Miracoli pack introduced by Kraft in 1961, a cardboard box that contained spaghetti, tomato sauce in a pouch, grated cheese and a herb-spice mix. Ready-made meals gained ground with the advent of microwave ovens, owned by one-third of West German households in 1989 (and virtually every single one could store frozen goods by then), a number that would double in the following three decades.34

Undeniably shopping and cooking were still women’s tasks. In 1964 a study found that most West German married men didn’t like their wives to work, although because of economic restraints, over one-third of all women with children under fourteen were doing just that. One-third of all husbands first of all expected their wives to be good at cooking and housekeeping. A study published in 1976 described the typical average housewife as 35 years old, having married at 21. She had two (school) children, both planned. Her husband was six years older than her and the sole earner, although she did some low-paid work before the children arrived. She had no higher education and enjoyed being a housewife, with a working day that stretched from 6.30 am to 10.30 pm. Without any hired help or servants, she cleaned the four-room flat, did the shopping, prepared three meals a day and supervised the children’s homework. She usually found a few hours for herself which she spent with household-related activities, such as doing her hair, needlework, repapering the walls or preserving and freezing fruit and vegetables. Weekends were more relaxed than weekdays.35

However, change was on its way. Alternative lifestyles like Wohngemeinschaften (groups sharing an apartment), Kommunen (communes) and Ehen ohne Trauschein (cohabitation) superseded patriarchal family structures and meals followed suit: one-pot dishes and pasta became favourites. Kitchens changed once more from purely functional cubicles back to more multifunctional spaces, with large tables and much social interaction. At the time rapid economic growth started to show its drawbacks. Industrialization and materialism were seen more and more critically, and it seemed time for another call back to nature, a resumption of the Lebensreform ideas of roughly a century earlier. In fact, Vollkornbrot, wholemeal bread, saw a revival. Berlin’s first (post-war) Vollkornbäckerei, wholemeal bakery, Weichardt opened in 1977. It strictly followed Rudolf Steiner’s anthroposophical principles and milled organically certified grain on three stone-cut mills on the premises. Besides championing environmental causes and nuclear disarmament, the burgeoning green movement fought for women’s emancipation. West German nutritionists were hard to convince, though. The midday family meal still stood for the integrity of the family, physical and spiritual health, economic stability and material well-being. To this day the pattern of limited preschool childcare followed by short school days with free afternoons makes life difficult for working parents.

In spite of the political protests against the establishment, the 1970s also saw the beginnings of a new generation of restaurants. When the first German Wimpy outlet (a British burger chain) opened in 1964 at Bochum central station, it was regarded with mere curiosity. West Germans were still into chicken: the Wienerwald grilled chicken chain of family restaurants had been eagerly embraced from its start in 1955 in Munich. Their slogan Heute bleibt die Küche kalt, wir gehen in den Wienerwald (today the kitchen stays cold, we’re going to Wienerwald) became immensely popular. In 1971, the year McDonald’s made its debut in Munich, the Austrian chef Eckart Witzigmann started at Munich’s Tantris restaurant. In 1979 he became the first German-based chef to be awarded the coveted three Michelin stars with his own restaurant Aubergine, also in Munich.

When the Michelin inspectors started to test German restaurants in the mid-1960s, their general verdict wasn’t exactly positive, but they put it diplomatically: ‘German cuisine doesn’t stand out through refined cooking techniques but rather the excellent and sumptuous composition of its dishes.’ One of Germany’s first Michelin stars had been awarded to the Keller family’s self-confidently French-orientated restaurant Schwarzer Adler in the Kaiserstuhl region near Freiburg in 1969. Both the young Witzigmann and Franz Keller junior had trained with the French chef Paul Bocuse, who in turn was a disciple of Fernand Point. True to its Roman past, but undoubtedly also due to the proximity of French colleagues and shopping opportunities accross the border in France, Germany’s southwest was a hotbed of restaurants that were up to French standards. But even here, somewhat oldfashioned sounding dishes featured on starred menus, such as ‘chicken breast Pompadour’, ‘veal liver St Tropez’ and ‘duckling Three Musqueteers’.

Bocuse’s bestseller Cusine du Marché was to change a lot of this. Published in 1976, it appeared the following year to great acclaim in a German translation, bringing the master himself to Frankfurt am Main for the occasion. The original title had been translated to Die neue Küche, new cuisine. While Nouvelle Cuisine in France went back to Michel Guérard and his fat-stripped, generally lean Cuisine Minceur, it all became one on German plates. Nouvelle Cuisine proved to be a great success in spite of some disparagingly calling it Ikebana-Küche because of the small and decoratively plated portions. Bocuse and his clever business advisers understood that French lifestyle, food and cuisine represented valuable export goods. France had started a large advertising campaign for French wine in Germany as early as 1959, and by 1975 Bocuse and his pâtissier colleague Gaston Lenôtre both had outlets at the Kadewe department store in Berlin. Even in Bocuse’s pared-down version, which was by no means as demanding or as complicated as the haute cuisine of old, French cooking was regarded as inherently superior. Whereas Bocuse in his original book addressed housewives as his target readership, the German edition was directed at mostly male Feinschmecker, gourmets, and Laien, amateurs.

Neither of them expected to find the right ingredients and quality needed for these dishes in Germany. Regional products such as oysters from the Northern Sea island of Sylt were still in their infancy and only started to be commercially viable from the mid-1980s. As we have seen, West German agricultural policy aimed at efficiency rather than the individual quality that was still to be found in France’s many deeply rural and less populated regions and its traditional centralized distribution system. Karl-Heinz Wolf, an ambitious restaurateur in Bonn, started to drive once a week to the wholesale market in Rungis near Paris to buy fish, poultry, crème fraîche and so on to supply his kitchen. He soon took orders for colleagues as well and in 1978 founded his hugely successful company Rungis-Express, importing fine French food on a commercial scale. Until the end of the 1980s, the menu at almost all ambitious German restaurants was determined by the twice-a-week delivery of the truck from Rungis-Express.

By then, some German chefs had gradually realized that their restaurants were not actually situated in France. It was a painful process of reorientation. When Gerhard Gartner started to use German products and look at his mother’s recipes for inspiration at his two-star restaurant Gala in Aachen from late 1986, colleagues and restaurant testers accused him of excessive nationalism and culinary fascism. They agreed that serving domestic pike-perch instead of loup de mer and ceps in place of truffles could make for new impulses to German cuisine, but most feared losing their customers if they offered German cheeses and waited for local asparagus and strawberries. In hindsight Gartner turned out to be one of the most prominent prophets of new German cooking. Chefs increasingly started to look for and encourage local producers as well as integrating regional recipes into their cooking. The onset of the Neue deutsche Küche or new German cooking was marked by a TV series and a book that went with it called Essen wie Gott in Deutschland (Eating like God in Germany). The title played on the German saying Leben wie Gott in Frankreich, living like God in France, which describes a sumptuous meal or way of life. The profession of chef became more attractive, with the stereotype changing from unreliable drunkard to star artist. New technical equipment made kitchen work less physically demanding, and during the 1980s the almost exclusively male profession slowly opened up to women, although they are still in the minority.

In a trend that trickled down from exclusive restaurants’ plates into cookbooks and food magazines, recipes and pictures of finished dishes became less decorated and ‘cleaner’. At the same time dieting became popular and all the internationally acclaimed versions from Atkins to Hay and South Beach found their way to Germany. So-called ‘light’ products, diet foods with reduced fat, sugar or fat content, became a very successful new market for the food industry. The first brand, called Du darfst (you may), was introduced by Unilever in 1973 with a low-fat margarine, followed by cheese, jam and spreadable sausage two years later. It was mainly directed at women and promoted not as reducing weight but as helping one to avoid putting it on – arguably an even larger market than those who needed to shed the kilograms. Other brands followed suit. Soon almost any industrially produced food product, including ready meals, was available in a reduced fat version with artificial sweetener replacing sugar.

The new energy in the restaurant kitchens quickly translated into a new kind of food journalism. Arguably the most successful German food journalist is Wolfram Siebeck, who started as a columnist for the youth magazine Twen, founded by German art director Willy Fleckhaus in 1959. The first restaurant review Fleckhaus commissioned took Siebeck to Maxim’s in Paris, following in the footsteps of his role model, the American writer Joseph Wechsberg. He later moved on to the food magazine Der Feinschmecker, published since 1975 by the Hamburg-based Jahreszeiten Verlag. His cookbooks have become bestsellers. Just like most of the chefs who brought restaurant cooking in Germany up to the French level, but did not create their own style (at least in the beginning), in Siebeck’s world French culinary culture has been the sole guiding star, and he frequently shows his impatience, even despair, with uneducated German palates and minds. His colleague Gert von Paczensky started as foreign correspondent, but went on to write restaurant reviews for the magazine Essen und Trinken (Food & Drink), published since 1972 by the Hamburg publisher Gruner & Jahr. On West Germany’s small screens, the actor Wilmenrod had been joined and followed by chef Hans Karl Adam (1915–2000), journalist Horst Scharfenberg (1919–2006), chef Max Inzinger (born 1945) and journalist Ulrich Klever (1922–1990). Up to the late 1980s food journalism and anything related to it was mostly focused on the harmless, pleasant aspects of food rather than critically analysing the larger picture of food production and environmental issues.

After the Second World War West German agricultural policy clearly aimed for higher productivity. Generous state subsidies went into far-reaching reparcelling of land for more efficient cultivation at larger farms, with some in narrow villages moving out to new buildings on greenfield sites. The number of tractors multiplied by six within a decade, combine harvesters went from rare experiments in 1950 to bringing in one-third of all grain in 1960, and milking machines became the norm.36 Like the European community as a whole, West Germany soon produced more than the market could take. Better seed quality, significantly increased use of fertilizers, pesticides and premixed feeds, improvements in animal breeding and the veterinary system, a growing number of greenfeed silos and the increased use of cutting and turning machines all combined to make ever-rising production levels. The number of dairy cows rose only slightly, but the yield per cow went up significantly. Milk and butter prices were a constant point of contention – consumers found them too high and often opted for (imported) margarine, although domestic butter production by the early 1950s was exceeding domestic demand. On top of that, neighbouring countries were pushing onto the West German market with their agricultural products, and threatened to stop buying German industrial products if they were obstructed. The French were not the only ones to target the German market: from 1961 Dutch butter and cheese was marketed with the help of Frau Antje, a pseudo-Dutch Meisje complete with wooden clogs and white lace bonnet, created by a German marketing agency.

Meanwhile intense mechanization and other investments led to increasing debts among farmers. In the mid-1960s wages were about one-quarter lower than in comparable industrial jobs. The Bauernverband (farmers’ organization) was always busy fighting for better economic conditions for its members. It tried to present them as a uniform group, although differences in their incomes were significant: in 1965 around 1.5 million agricultural businesses in total ranged from large farms to very small ones run as a side concern. Of these, 143,000 had more than 20 hectares, 300,000 were family-run with 10 to 20 hectares and around 1.1 million were even smaller than that. Children’s work was amazingly common. It was normal that children over seven in rural areas had to help out during the summer. When they reached the ages of thirteen or fourteen their parents were reluctant to let them go to school any longer, feeling they would be more useful at home. Non-farming parents in tight circumstances also sent their children to work on farms. Although officials were anxious to preserve traditional social structures in rural areas, it shouldn’t surprise us that the numbers of those working the land went down due to modernization: from almost one-quarter of the employed West German workforce in 1949 to 13.3 per cent in 1960 and 6.5 per cent in 1975.37

The landscape kept changing. Between 1980 and 1990 the number of farms decreased by another fifth, while total agricultural production, particularly of wheat, sugar beet, milk and eggs, rose by 14 per cent.38 Rural districts tried to attract industrial enterprises, and commuting farmers who had a second occupation to make ends meet contributed even further to mixing of rural and urban lifestyles and living standards. In the 1970s rural towns and villages that were not situated in the catchment areas of the industrial cities had been considered doomed, but by the mid-1980s about half of the West German population lived in rural areas, although only 3 per cent of the total population were full-time farmers. Nevertheless village structures changed as supermarkets came to dominate the retail trade; with increasing motorization they were often situated on the edge of towns and cities.

Artists using food as their medium often were more politically minded and critical than the food journalists of the time. The best known among them is Joseph Beuys, who frequently combined animal fat with felt in his sculptures, but also used butter, chocolate, fruit or sauerkraut in his Partitur der Sauerkrautfäden (The Sauerkraut Strings’ Score) (1969). The same year, he created a piece called Beethovens Küche (Beethoven’s Kitchen) for the Argentine composer Mauricio Kagel’s film Ludvig van. He refused to drink wine from the German state estates in the Rheingau (Ich trinke keinen Staatswein!, 1974) and in 1977 planted potatoes in front of a Berlin gallery as a performance. His colleague Sigmar Polke, painter and photographer, had ‘discovered’ potatoes for his sculptures and ideas in the 1960s. The German-speaking Swiss artist Daniel Spoerri is best known for his Fallenbilder, in which he preserved the debris left on tables after long dinners. In 1968 he started a bar, restaurant and gallery in Düsseldorf where Beuys pinned baked herringbones to the wall, calling them ‘Friday objects’. The Swiss-German Dieter Roth, another Eat-Art representative, used chocolate as his favourite medium for sculptures and portraits, documenting decay. The Viennese Peter Kubelka developed a unique combination of experimental filmmaking and cooking and taught both at the Frankfurt Städelschule from 1978 to 2000. He pronounced cooking to be the mother of all arts. German enfant terrible Martin Kippenberger taught at the Städelschule in the 1990s; his prolific work in the 1980s included frequent quotations from Joseph Beuys’s Wirtschaftswerte of 1976, multiples of East German packed foodstuffs signed by the artist.

A signature dish of the time was Dialog der Früchte (Fruit Dialogue), created by Hans-Peter Wodarz at the Ente Vom Lehel restaurant in Wiesbaden at some point in the mid-1970s, as culinary legend has it, originally for Andy Warhol. The swirled pattern of three different fruit purées, highly decoratively served in a large soup plate, replaced the sorbet often served between starter and main course and in its fresh straightforwardness was symbolic of the new health consciousness. In 1970 the German sports association started the get-in-shape Trimmdich movement. A legal blood alcohol limit behind the wheel was introduced in 1973, originally set at 0.8 milligrams of ethanol per gram of blood, and reduced to 0.5 in 1998. In both parts of Germany alcohol consumption had risen with the post-war economic recovery in the 1960s. Alcoholism was viewed first as a sort of punishable criminal behaviour, then increasingly as an individual mental illness to be treated in closed institutions. The frequently abominable conditions encountered there were the subject of a undercover investigation and report by the journalist Günter Wallraff. The national stereotype however swerved away from the boozer to make way for the hardworking and reliable German who enjoyed the occasional recreational tipple, linked to German festivals like Oktoberfest. In fact the trend in alcohol consumption has been going down since 1980 and as of 2010 was below 10 litres of pure alcohol per head each year.39

Dialog der Früchte or dialogue of fruit, a swirl of puréed fruit, replaced the traditional sorbet in the 1980s in trendy high-end restaurants. The signature dish was created by Hans-Peter Wodarz, one of the key players in Germany’s Michelin-starred Nouvelle Cuisine scene. Like many other dishes at the time, it was documented by food photographer Johann Willsberger in his hugely influential magazine Gourmet.