“A Bacardi,” says Nick to the waiter. He looks to Nora, who nods. Nick motions to the waiter and adds, “Two Bacardis.” Says Nora with a straight face to the waiter, “I’ll have the same.” The waiter returns with four Bacardis.

—Another Thin Man, 1939(1)

Great women scientists are invisible until someone specifically looks for great women scientists. Then they are plentiful. But no one has to look for great male scientists. Great male scientists always appear on lists of great scientists.

—Jo Handelsman and Rosalind A. Grymes, 2008(2)

Why does every black person in the movies have to play a servant? How about a black person walking up the steps of a courthouse carrying a briefcase?

—Myrna Loy to MGM Executives, ca. 1934(3)

I cannot and will not cut my conscience to fit this year’s fashions.

—Lillian Hellman in 1952, Scoundrel Time, 1976(4)

IT’S BEEN A LONG AND WEARISOME SEASON in American politics, a scoundrel time in which issues of race and gender have been crudely exploited. Yet, whatever the outcome was of the 2008 elections, two barriers to democracy in America have surely been breached. Never before has a black man carried a briefcase so high up the courthouse steps, never before has the glass ceiling been so effectively challenged. Cynics may gloat—“Guns, God, Lipstick? This is what feminism has come to?”(5) or “If Obama was a white man, he would not be in this position”(6)—but the rules of the political game have changed—forever, one would hope.

At least with respect to gender, the rules have also changed in science and I’m going to argue that the silver screen is at least partly responsible. The notion came to mind early this fall, when a quick run-through The Thin Man series on Netflix coincided with a sparkling editorial in the journal DNA and Cell Biology. Titled “Looking for a Few Good Women?,” it asked why women have been short-changed in the glittering prizes of science. Its authors, Jo Handelsman of the University of Wisconsin and Rosalind Grymes of the University of California Santa Cruz, point out that women have received almost half of all U.S. doctoral degrees awarded in the life sciences over the last 20 years. They constitute 32 percent of all tenure-track faculty and 26 percent of full professors in the life sciences.(2) That’s one part of the story.

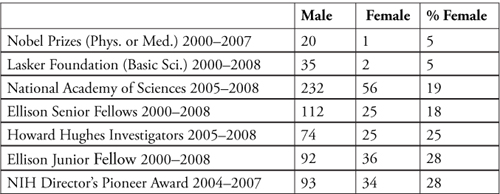

Handelsman and Grymes, officers in the vigorous Rosalind Franklin Society,(7) correctly point out that women are underrepresented in our academies and among winners of the Lasker and Nobel Prizes. Their data, with some additions, are presented in Table 1. The steeper the slope, the higher the prize, the tougher it is for talented women, who now form a large pool, to gain the glittering prizes. “What can be done?” they ask, and suggest that “We need to look for great women scientists, and if we use a rigorous process of review, we will see them. Lots of them.”(2)

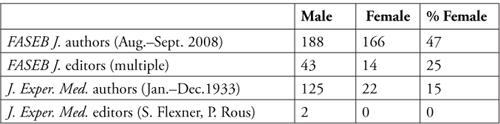

I was suddenly concerned that The FASEB Journal, a journal for which I am responsible, might not be keeping up its part in gender neutrality: we should have pretty much as many women as men among our authors. And since our editors are all full professors, at least a quarter of our editors should be female.

Table 1: Gender Distribution of Honor Awards in the Life Sciences

Data from References 2 and 8.

Table 2: Authorship and Editorship in Life Science Journals

In Table 2 are listed the gender of all authors of refereed articles in the August and September issues of the journal, in so far as our imperfect knowledge of gender-specific first names permits. I compare this to a comparable journal, The Journal of Experimental Medicine of 1933, the year Dashiell Hammett’s The Thin Man was written—the film appeared a year later. The JEM is a reasonable control, since at the time it published the sort of broadly interdisciplinary articles that The FASEB Journal has been publishing only since 1987.

Today’s numbers may not be entirely satisfactory, but in the life sciences, women are better represented than in the days of speakeasies and breadlines and of journals controlled by one or two very eminent seniors. And yet . . .

It was clear to Handelsman and Grymes, and painfully evident to me as well, that from this ample supply of good to great women scientists (25 percent of Hughes Investigators!), perhaps more than one or two female laureates might have been honored at dinner in Stockholm or lunch in Manhattan. One should have thought that a pool of fine Investigators is waiting to be tapped.

That’s where Myrna Loy comes in. She broke the glass ceiling in the private investigator game, and went on to play an honorable role in the scoundrel time of the McCarthy Era. Myrna Loy, and the couple who inspired the characters of Nick and Nora Charles in The Thin Man series—Lillian Hellman and Dashiell Hammett—can remind us of the contribution made to gender equality by the progressives in our midst. They were part of the Popular Front in the New Deal era, crusaders for social justice and family planning, for contraception and reproductive research, for women’s education and childcare. Without those “pinkos” and “fellow travelers,” as Joseph McCarthy called them, there’d have been far fewer opportunities for women to leave their Kinder, Küche und Kirche (kids, kitchen and church) to pursue careers in the life sciences.

Hellman and Hammett were clearly the models for Nick and Nora, and they spoke to each other as such: Hammett wired from Hollywood to Hellman in New York as he was adjusting Another Thin Man: “SO FAR SO GOOD ONLY AM MISSING OF YOU PLENTY LOVE NICKY.”(9) They surely would be welcomed by today’s Rosalind Franklin Society, happy that Nick and Nora Charles “recognized and fostered” the image of female competence on the screen.(10) The poet Frank O’Hara had it right: it wasn’t The Nation, The New Republic or Partisan Review that carried the torch for the Popular Front and equal recognition, but the movies:

Not you, lean quarterlies and swarthy periodicals

with your studious incursions toward the pomposity of ants,

. . . but you, Motion Picture Industry,

it’s you I love!. . . Myrna Loy being calm and wise, William Powell in his stunning urbanity. . . .(11)

The Myrna Loy who in six films of The Thin Man series played Nora Charles was probably a more effective messenger of progress than the Myrna Loy who fought to abolish the House Un-American Activities Committee. Loy and Powell cast the mold for other male–female pairs of equal wit and wisdom: Hepburn–Tracy, Rogers–Astaire and Bacall–Bogart. At a Lincoln Center tribute to Myrna Loy, Lauren Bacall acknowledged that debt and asked:

And to meet whom did Franklin D. Roosevelt find himself tempted to call off the Yalta Conference? Myrna Loy. And to see what lady in what picture did John Dillinger risk coming out of hiding to meet his bullet-ridden death in an alley in Chicago? Myrna Loy, in Manhattan Melodrama.(12)

Her wisdom was not limited to screenplays. FDR named her an assistant to the director of military and naval welfare for the Red Cross in World War II. She was later appointed a member-at-large of the U.S. Commission to UNESCO.(13)

Before Nick and Nora Charles emerged as co-investigators, detective fiction and “mystery” stories were dominated by omniscient males. The great detectives used wit and whimsey as weapons; they were never simply funny. Arthur Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes (1887), Agatha Christie’s Hercule Poirot (1920), Dorothy Sayer’s Lord Peter Wimsey (1923) and H. C. McNeile’s Bulldog Drummond (1920) ruled the genre with guile and style; Miss Marple appeared as a village snoop in 1927. It wasn’t until Dashiell Hammett himself broke the mold with Sam Spade (1930) that irony became de rigueur. Nick and Nora, on page and on screen floated, flirted, drank and joked:

NICK:

“I’m a hero. I was shot two times in the Tribune.”

NORA:

“I read where you were shot five times in the tabloids?”

NICK:

“It’s not true. He didn’t come anywhere near my tabloids.”(14)

And when it came to investigation, Nora set the mold for how an investigator differs from a detective. In the original The Thin Man book, Hammett has Nora set out the method as Nick nods off:

Nora yawned again. “That may be good enough for a detective, but it’s not convincing enough for me. Listen, why don’t we make a list of all the suspects and all the motives and clues, and check them off against—” “You do it. I’m going to bed.”(15)

It may be no accident that Nick became a private “investigator”—Hammett had worked as a Pinkerton detective before he took up his pen. Like Hammett, Nick Charles has retired from being a detective for hire, and now he and Nora pursue crime as independent investigators rather than working for hire as detectives, a police rank. (Those of us in academic science can appreciate the difference: you have to raise your own money as an investigator.) It was said of Hammett, and of Nick Charles, that he was doing “an intensive study of the liquor problem from the consumer’s standpoint.”(16) Nick and Nora were the models of co-principal investigators with more than a touch of class. They were also models of urban charm and sophistication, mixing martinis with wisecracks on the silver screens of the world.

In contrast to the neat gloss of Nick and Nora, Hellman and Hammett had messy personal lives. Both were boozers, chain-smokers and contentious. Their literary careers were troubled by rivalry, enmity and betrayals. John Leonard summed up their messy affairs:

Never mind their talent. We are talking about Hollywood. It’s now my view that one promiscuous drunk found another to reciprocate, that they spent thirty years jockeying for the perfect vampire-bite position, and that, as their lips locked, so did their wounds.(17)

But they both had moments of great courage. Hellman received a subpoena to appear before the House Un-American Activities Committee in 1952. She was asked to disclose the names of her associates in film and the theater who could have been Communists or fellow travelers. She refused to comply and published her response in The Nation:

To hurt innocent people whom I knew many years ago in order to save myself is, to me, inhuman and indecent and dishonorable. I cannot and will not cut my conscience to fit this year’s fashions, even though I long ago came to the conclusion that I was not a political person and could have no comfortable place in any political group.(4)

Well, not really: she was indeed a convinced fellow traveler. So be it. But in consequence, Hellman’s name wound up on Hollywood’s blacklist and she was stuck with an inexplicable bill by the IRS. She survived and her plays such as The Little Foxes and The Children’s Hour continue in performance the world over.

A disabled veteran of World War I, Dashiell Hammett again enlisted in the Second World War at the age of 48, became a sergeant and was stashed away in the Aleutians, suspected of “pre-mature anti-Fascism.” After the war, he was a member of the Civil Rights Congress, a liberal political group that was targeted by the FBI as being a communist front. When he refused to name contributors to the organization and was sentenced to six months in jail. In a 1953 episode that has resonances with the political wars of 2008, Sen. Joseph McCarthy asked him if the government should fund purchases for library books written by avowed communist sympathizers. Hammett replied, “If I were fighting Communism, I don’t think I would do it by not giving people any books at all.”(18) His literary career dissolved in chronic lung disease and booze, and he died penniless in Katonah, New York, in 1961. According to his wishes, this “pinko” father of Nick and Nora, the lover of Lillian Hellman, was buried in Section 12 of Arlington National Cemetery. FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover attempted to block the burial but was overruled by the Dept. of Veterans Affairs.(18) His simple gravestone reads: SAMUEL D HAMMETT MARYLAND TEC 3 HO CO ALASKAN DEPT WORLD WAR I & II MAY 17 1894 JANUARY 10 1961.