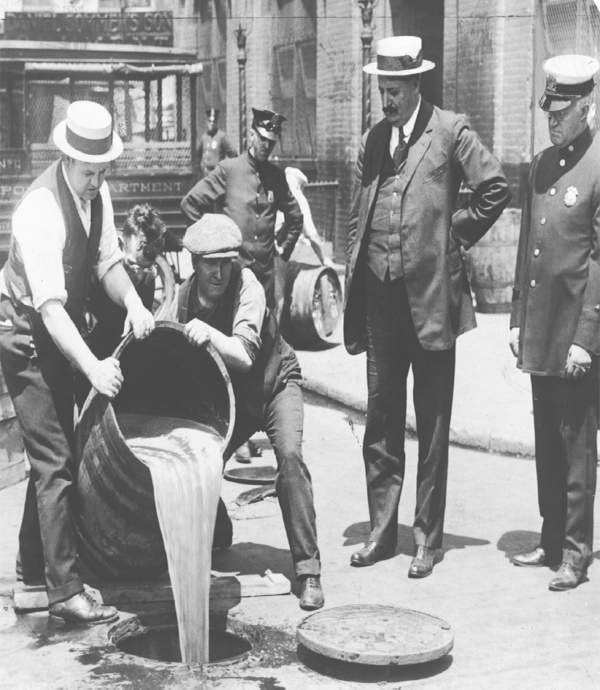

Deputy Police Commissioner John A. Leach (right) watching agents pour liquor into a sewer following a raid in New York at the height of Prohibition (ca. 1921). (The Art Archive at Art Resource, NY)

BEGINNING in the late nineteenth century, prohibition advocates successfully passed legislation at the local and state levels that banned the manufacture and sale of alcoholic beverages. The laws did not make much difference, however; most drinkers just crossed county or state lines and bought liquor where it was legal. Moreover, anti-prohibition forces had a habit of repealing the “dry” laws as soon as they gained the legislative upper hand. As a result, prohibitionists resolved that the only real solution would be an amendment to the U.S. Constitution. Only then would the manufacture and sale of alcohol be illegal in every state, and only then would the alcoholic scourge that afflicted America come to an end. Prohibition amendments had been introduced into Congress repeatedly since 1876, but they had never made it out of congressional committees. In 1913, however, a prohibition amendment finally made it out of committee and reached the House of Representatives—and it seemed to have a chance of passage. Prohibition advocates immediately went to work organizing their constituencies, sending letters, signing petitions, meeting with legislators and their staffs, and publishing articles in newsletters, newspapers, and magazines in support of the amendment.

Despite the optimism of prohibition advocates, it was unlikely that the amendment would pass. At the time, only five amendments to the Constitution had been ratified since the Bill of Rights was ratified in 1789; the last three of these had been approved immediately after the Civil War. When the House voted on the prohibition amendment in December 1914 it received a majority of the votes, but not the two-thirds majority that was required for passage of an amendment. This failure only encouraged prohibitionists to work harder to elect a more favorable Congress in 1916. Prohibition candidates fared well in the election that year, but still not enough votes were received to pass an amendment.

But then, fate intervened. Europe had been mired in World War I for three horrific years. In hopes of breaking the stalemate and winning a quick victory, Germany began unrestricted submarine warfare against Great Britain in February 1917. Seven American merchant ships were sunk by German subs, and the United States declared war on Germany on April 6, 1917. Patriotic fever swept the nation, and leaders of prohibition organizations made certain that prohibition and patriotism were linked in the public mind. Germans were the enemy overseas, and at home it was the brewers—many of whom were German-born and some of whom had supported Germany before the United States entered the war. Supporters of prohibition exploited anti-German sentiments by publishing posters denouncing the “pro-German brewers and liquor dealers” who were identified as “A Disloyal Combination.”1 Distillers could also be labeled “unpatriotic” for using grain needed for the war effort.

The strategy worked: Congress passed legislation to prevent grain from being distilled into alcohol, and brewing was restricted as well. Finally, in 1917, the U.S. Senate and House of Representatives approved the prohibition amendment with the requisite majorities. All that was needed now was for three-quarters of the states to ratify the amendment, and prohibition would become the law of the land. Prohibition leaders believed this would happen, but that it would take years to achieve. They were wrong. Slightly more than a year later, on January 16, 1919, the Eighteenth Amendment was approved by the final state legislature needed. Congress approved enabling legislation called the National Prohibition Act, popularly called the Volstead Act; this act, passed over President Woodrow Wilson’s veto, effectively banned the manufacture, sale, and importation of alcoholic beverages in the United States, making them illegal from January 17, 1920. With the onset of Prohibition, American drinking habits would never be the same.

In colonial New England, drunks were dealt with severely. Sometimes they were put in stocks and ordered to wear the scarlet letter (in this case, “D”) to identify themselves as drunks. In 1633, John Winthrop, the governor of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, found one Robert Cole guilty of “having been oft punished for drunkenness.” Cole was “ordered to wear a red D about his neck for a year.”2 Increase Mather, the president of Harvard College, noted in 1673 that alcohol was “a good creature of God and to be received with thankfulness, but the abuse of drink is from Satan; the wine is from God, but the Drunkard is from the Devil.”3 By 1686, Mather was focusing his criticism on rum. It was “an unhappy thing,” he wrote, “that of later years a kind of Strong Drink hath been common amongst us, which the poorer sort of people, both in Town & Country, can make themselves drunk with, at cheap & easy rates. They that are poor and wicked too (Ah most miserable creatures), can for a penny or two make themselves drunk.”4

At the urging of local ministers, colonial governments tried to control taverns through licenses and by regulating their opening hours of business. Another way of limiting alcohol was through taxes. But laws need to be enforced, and this proved difficult because the men charged with enforcement were often heavy drinkers themselves, and they preferred to maintain friendly relations with their neighbors. Nevertheless, governments continued to pass ordinances in an attempt to limit drinking. In 1712, the Massachusetts Assembly passed an “Act against Intemperance, Immorality and Profaneness, and for the Reformation of Manners.” This law was aimed at tightening licensing procedures and controlling the times and days that taverns could operate, among many other restrictions. But the law—like most passed before and since—proved impossible to enforce, and it was eventually repealed.5 Still, such failures did not end attempts to control the sale and consumption of alcohol.

When Georgia was established in 1732, its founders banned spirits to “prevent the pernicious effects of drinking Rum” among the settlers. But the law was flouted, and the city of Savannah was soon filled with taverns.6 Seven years later, the law was repealed. The main reason given for the repeal was that Georgia was at a competitive disadvantage compared with South Carolina when trading with the Indians, who wanted liquor in exchange for furs, food, or land. The amount of alcohol guzzled by Americans worried some of the founding fathers, who certainly drank their share. In 1796, John Adams described a worker on his farm as “a beast associating with the worst beasts in the neighborhood, running to all the shops and private houses, swilling brandy, wine, and cider, in quantities enough to destroy him. If the ancients drank wine as our people drink rum and cider, it is no wonder we read of so many possessed with devils.”7

Drinking was socially acceptable, even when vast quantities were downed. But as stronger drinks, such as rum and whiskey, became more common and less expensive, concern with drunkenness increased. Religious groups, including the Quakers and Methodists, were particularly opposed to distilled spirits. A Philadelphia Quaker named Anthony Benezet argued in The Mighty Destroyer Displayed (1774) against the consumption of any drink that was “liable to steal away a man’s senses and render him foolish, irascible, uncontrollable, and dangerous.”8

Medical professionals had their own concerns about excessive drinking. Benjamin Rush, America’s foremost physician in the late eighteenth century, drank mainly coffee and tea, as well as a “glass of or glass and a half of old Madeira wine” after dinner, but he never took “ardent spirits in any way nor at any time.” Among the first pamphlets Rush published was Sermons to Gentlemen on Temperance and Exercise, which appeared in 1772. Five years later, Rush argued against giving Continental soldiers rum, arguing instead for “plentiful draughts of milk and water.”9 For farm workers, he recommended a number of alternatives to distilled spirits: plain water, hard cider, malt liquors, and wines; water mixed with maple syrup, molasses, or vinegar; buttermilk, coffee, tea, or even water “suffered to stand some time upon parched Indian corn.” Rush later estimated that 4,000 people lost their lives every year due to the consumption of hard liquor.10 The views of Rush and like-minded others, however, did not generate much interest among most Americans, and it would be decades into the nineteenth century before temperance became a major movement in the United States.

After the American Revolution, alcohol consumption rose sharply. The United States had 2,579 registered distilleries in 1792; eighteen years later, this had increased to 14,191, which churned out 25 million gallons of spirits annually.11 In addition, there were numerous unlicensed commercial stills throughout the country and many Americans operated one in their own homes. As one observer wrote of the period:

Intemperance in liquors had gone to very extraordinary lengths. The practice of dram-drinking had become almost universal. French or Spanish brandy, West India and New England rum, foreign and domestic gin, whisky, apple brandy, and peach brandy, made a variety which recommended itself to individual tastes. But besides this choice, there were numerous artificial compounds, in which fruit of various kinds, eggs, spices, herbs, and sugar, were leading ingredients. Thus, at home, or at the bars of taverns, there was a continual dabbling in spirits, grog, sling, toddy, flip, juleps, elixirs, &c., as if alcohol in one or other of its seductive disguises, had become a necessary of life.12

In 1810, Americans drank more than 4.5 gallons of pure alcohol each, and it was also estimated that about 6,000 Americans died each year because of their drinking.13 As the young country came of age, alcohol use continued to increase. In 1821, the Harvard academic George Ticknor complained to Thomas Jefferson that Americans were “already affected by intemperance; and if the consumption of spirituous liquors should increase for thirty years to come at the rate it has for thirty years back we should be hardly better than a nation of sots.”14 By the mid-1820s, New York State had 1,129 distilleries and New York City alone had more than 1,600 “spirit sellers,” who sold whiskey for 38 cents a gallon. According to one British observer, this abundance of sellers and cheap price meant that “the people indulge themselves to excess, and run into all the extravagancies of inebriety.”15 British writer Frances Trollope, who visited America in the late 1820s, reported that in Maryland whiskey flowed at the fatally cheap rate of 20 cents a “gallon, and its hideous effects are visible on the countenance of every man you meet.” The price of whiskey soon dropped to a dime.16 By 1830, alcohol consumption by Americans over the age of fifteen was estimated at seven gallons per capita, most of it in the form of whiskey.

Abetting the rise of the temperance movement was the “Second Great Awakening.” This religious revival began in the 1790s when Methodist, Baptist, and (to a lesser extent) Presbyterian preachers rode across America, especially in New England and later the Midwest, espousing a new evangelism. The church and camp meetings led by these men were attended by hundreds of thousands of Americans, particularly in rural areas. The social activism that emerged from this religious fervor eventually launched movements to end slavery, reform prisons and education, promote missionary activities, and encourage women’s suffrage—but its first and most glorious cause was temperance.

The Massachusetts Society for the Suppression of Intemperance, founded in 1813, endeavored to persuade people to abstain from alcohol by describing its harmful effects; members of the society tried to convince drinkers that their lives would be far happier and more rewarding without alcohol. They formulated a pledge by which drinkers promised publicly to reform and drink no more.17 Meanwhile, temperance preachers spoke out against alcohol, and temperance tracts and sermons were widely published and distributed. Lyman Beecher, a Presbyterian minister, gave six sermons on temperance in 1826; they were printed and reprinted for years.18

Beecher cofounded the American Society for the Promotion of Temperance (later the American Temperance Society) in Boston. It was intended to be a national umbrella group for temperance organizations, and it succeeded: within five years of its founding, there were 19 affiliated state societies with more than 2,200 chapters and more than 170,000 pledged members.19 When the French historian and politician Alexis de Tocqueville arrived in America in 1831 and heard that “a hundred thousand men had bound themselves publicly to abstain from spirituous liquors,” he thought it was a joke, for he “did not at once perceive why these temperate citizens did not content themselves with drinking water by their own firesides.” But when he wrote Democracy in America (1835), Tocqueville concluded that “these hundred thousand Americans, alarmed by the progress of drunkenness around them, had made up their minds to patronize temperance.”20

More than 5,000 temperance societies with a total of 1.25 million members were operating in America by 1833. Two years later, there were 8,000 societies with 1.5 million members.21 In May 1833, a total of 400 delegates from twenty-one states assembled in Philadelphia for the first national temperance convention. The delegates formed the American Temperance Union, which would help guide the movement until the Civil War.22

Despite the growth of temperance organizations, Americans were drinking more than ever. In 1830 it was estimated that 37,000 people died annually because of strong drink. The Encyclopaedia Americana reported in 1832 that alcohol “was responsible for three quarters or four fifths of the crimes committed in the country, for at least three quarters of the pauperism existing, and for fully one third of the mental derangement.” In addition to the human and family tragedies associated with alcohol, there were other costs as well: the financial cost of housing prisoners who committed crimes while intoxicated, the loss of laborers who were too inebriated to work, and the alcoholic paupers who flooded American communities.23 It was estimated that in New York City alone, three-quarters of crime and pauperism was related to liquor.24 None of these statistics was supported by evidence; they were only opinions frequently expressed by temperance advocates.

The New York State temperance convention proposed a very mild resolution supporting total abstinence in 1833, but it was withdrawn due to lack of support. Around that same time, the Quarterly Temperance Magazine published several responses by leaders who opposed the resolution. Only two supported complete abstinence, of whom one wrote, “The only means of redemption and preservation for the intemperate is total abstinence from all intoxicating drinks.” Some prohibitionists saw no reason to ban wine, beer, or cider. They perceived the resolution as an attempt to dilute the temperance pledge—clearly the real evils were rum, whiskey, and brandy.25

Proponents of total prohibition marshaled their arguments. They felt sure that drunkards who had signed the temperance pledge would have a sip of wine or a glass of beer and begin a slow slide back to their old ways. Abstinence backers collected testimonials from medical professionals about the evils of all alcohol. When the New York State temperance convention met the following year, it passed the original resolution, making it the first state temperance society to endorse total prohibition.26 The following year, the Massachusetts temperance society passed a similar resolution banning all distilled and fermented beverages. In 1836, when the American Temperance Union held its second national convention in Saratoga Springs, New York, it also passed resolutions opposing all alcoholic beverages.

Temperance advocates used sermons, books, tracts, hymns, mass meetings, and cartoons to make life uncomfortable for those who manufactured, sold, and drank alcohol. Temperance orators drew large crowds, and two temperance plays found wide audiences. As the temperance fervor increased, public drinking became less acceptable, and moderate drinkers found themselves in an especially uncomfortable position, despised by both teetotalers and hard drinkers. Because of the efforts of the temperance societies, alcohol consumption dropped sharply, such that by 1845 Americans drank an estimated 75 percent less alcohol than they had in 1830. An estimated 4,000 distilleries closed—although many reopened once temperance advocates moved on to harass other distilleries and the pressure was off.27

As temperance leaders continued to press their agenda, several states passed laws that banned or greatly restricted the sale of alcoholic beverages. In 1841, Maine became the first state to pass such a law, and others soon followed. These laws, however, proved impossible to enforce, and the selling and drinking of alcohol simply moved out of the public eye. Over the next decade, most state laws were repealed or annulled by state courts.

The legal setbacks of the 1850s were minor compared with the widespread collapse of temperance movement during the Civil War and the return to hard drinking, especially among soldiers.28 During and after the war, saloons opened everywhere, and there was no shortage of customers. By 1870, Manhattan had 7,071 licensed suppliers of liquor and probably an even greater number of illegal establishments. A 1897 survey in Manhattan found a ratio of one liquor distributor to every 208 residents.29 A 1899 police report in Chicago revealed that half the city’s population went into a saloon every working day.30 A major reason for this was the free lunches offered on bar counters—all patrons had to do was buy a drink. This ensured that customers acquired the habit of drinking liquor at noon, and this helped to develop a regular clientele for saloons and bars. Moreover, the food served at saloons was often salty, which increased the desire to drink, and the ingredients served at the free lunches were low cost. In Chicago, the meatpacking plants were said to give bars spoiled salted meat to use in their free lunches.31

After the Civil War, new temperance societies emerged to relaunch the crusade against alcohol. Ohio was the birthplace of three most important of these groups: the National Prohibition Party (organized in Cleveland in 1869), the Women’s Christian Temperance Union (started in Cleveland in 1874), and the Oberlin Temperance Alliance (also founded in 1874). Of these, the most important was the Oberlin Temperance Alliance, which morphed into the Anti-Saloon League of Ohio in 1893, and Howard Russell, a lawyer and Congregationalist minister, became its general superintendent. The Anti-Saloon League had a single objective: prohibition. No other issue mattered. It organized the evangelical churches, including the Baptists, Congregationalists, Methodists, and Swedish Lutherans. Its local affiliates had at least 75 percent clergymen on their boards; on Sundays, tens of thousands of their parishioners heard the league’s message. Just as important, its staff members were paid—not volunteers, as in other organizations—thereby ensuring their dedication and enhancing the effectiveness of the league.

Temperance Beverages

A challenge facing temperance advocates was what to offer the public as a substitute for alcoholic beverages. In the mid-nineteenth century, the increased availability of safe water made it a viable option. Medical authorities had begun to understand the relationship between sanitation and wells. In rural areas, farmers needed to put some distance between their waste pits and their fresh water wells, which also needed to be dug much deeper. In urban areas, authorities modified municipal water systems to include delivery infrastructure that made safe water available throughout the city. Where population outstripped fresh water supplies, cities such as New York embarked on massive projects to bring safe drinking water from surrounding areas. As a result, by the early twentieth century, clean and pure water was available in most American cities. Such improvements in water supplies eliminated one argument offered by those who drank alcohol (that water was unsafe), and drinking water became a reasonable alternative to beer, wine, cider, and spirits. This was especially important in restaurants, where ice water was automatically served, especially to female diners.

Two other alternatives to spirits were coffee and tea. Both had been on American tables since colonial days, but it was not until after the Civil War that affordable coffee became available throughout the United States. Coffeehouses became centers of temperance activities in the United Kingdom, but not in the United States. Tearooms emerged in the United States in the late nineteenth century and became popular, especially with women. At about the same time that water systems were improving, scientific discoveries, technological improvements, and the passage of laws helped create a safe milk supply. Milk became the most important drink for children, who previously would have consumed ciderkin (weak cider) and other mildly alcoholic beverages.

During the mid-nineteenth century, drugstore owners began experimenting with nonalcoholic creations that they promoted as temperance drinks.32 After the Civil War, such concoctions were marketed locally. Charles E. Hires, a Philadelphia druggist, invented root beer, which he advertised as “The Great Temperance Drink” and “a temperance drink for temperance people.”33 This designation was challenged by temperance leaders, who believed that root beer contained alcohol. But after reputable chemists analyzed the drink and concluded that it contained only water, sugar, and root extracts, the doubters made public apologies.34 Grape juice, also promoted as a temperance refreshment, became popular during the late nineteenth century. In 1896, a soft drink called Countie’s Roma Punch, bottled in Boston, proclaimed itself “The National Temperance Drink.”35 Coca-Cola also was advertised as a temperance beverage, and it flourished under that banner until the temperance movement became concerned about cocaine.36

Temperance advocates became impatient with the long, slow grind of lobbying political bodies persuading sinners to renounce alcohol and promoting alternatives to liquor. Some brave souls were willing to take direct action. One such person was six-foot-tall Carrie Amelia More, who lived much of her early life in rural Missouri. Carrie married a doctor named Charles Gloyd, who turned out to be an alcoholic (or so she later claimed). After Gloyd died, Carrie Gloyd married a minister named David A. Nation. The couple eventually moved to Medicine Lodge, Kansas, where Carrie Nation founded a chapter of the Women’s Christian Temperance Union. The chapter embarrassed saloon keepers, bartenders and customers to the point that some saloons shut their doors. But they could not keep the locals from patronizing liquor establishments in neighboring Kiowa, Kansas, and these establishments resisted the group’s efforts.

Then Carrie Nation had a vision that urged her to take stronger action against the sale of alcohol. In 1899, she went to Kiowa and began throwing rocks at liquor bottles inside saloons. The rocks caused little damage, so in 1901 she upgraded her weaponry to a hatchet and proceeded to perform “hatchetations” by marching into saloons and smashing mirrors, bottles, slot machines, faucets and hoses connected to beer barrels, and anything else that she could before she was arrested. Despite arrests and fines—which she refused to pay—Nation continued to enter and vandalize saloons in Wichita, Kansas City, and elsewhere. Her bold actions generated publicity, and other women jumped on the anti-liquor bandwagon, forcing local bars and saloons to close and supporting efforts to prohibit the sale and distribution of alcohol.37 Physical attacks could only go so far, however. If prohibition were to succeed, it needed a very different strategy, and Wayne Wheeler was just the man to create it.

Wheeler and the Anti-Saloon League

Wayne B. Wheeler studied at Oberlin College, where he had worked part-time with the Anti-Saloon League. He continued to do so while studying at Western Reserve Law School. Wheeler became an attorney in 1898 and began working full-time for the league. At that time, the Anti-Saloon League was a small group that advocated complete prohibition. Many other organizations, such as the Women’s Christian Temperance Union and the National Prohibition Party, had far larger national memberships. Therefore, it was unlikely that a small state organization, like the Anti-Saloon League, would have much of an influence outside Ohio.

Wheeler absorbed himself in lobbying for prohibition legislation in Ohio. The best way to guarantee appropriate legislation, he thought, was to elect candidates who supported prohibition and defeat those who opposed it. The league soon became a nonpartisan group with but a single issue: prohibition. If a Democratic candidate supported prohibition, he would have the league’s support; if a Republican was for prohibition, the league would throw its weight behind his campaign. No other issue mattered. The Anti-Saloon League worked cooperatively with other temperance groups, such as the National Prohibition Party and the Women’s Christian Temperance Union, to focus on electing prohibition supporters and passing legislation. The league mobilized its forces for electoral victory; if an elected official later reneged and voted against prohibition legislation, the league did everything possible to defeat him in the next election.

Wheeler’s strategy worked: the Anti-Saloon League influenced many local and state elections; as a result, Ohio communities and the state legislature passed laws that restricted or prohibited the sale of alcohol. The league expanded its operations to other states, with similar success. As local and state victories piled up, the league became the leader in the prohibition movement.

As the Anti-Saloon League gained national visibility, funds rolled in; the league used the money to pay its staff, churn out propaganda, and organize campaigns for and against candidates. The league also created a speakers bureau that, at its height, boasted more than 20,000 prohibition advocates, including big names such as the politician William Jennings Bryan, a teetotaler. The groups that hosted the speakers were required to request a hefty contribution from the audience for the league. These tactics worked. Prior to 1900, just five states had adopted prohibition legislation, as had many counties and cities. But then the dominos tumbled. In 1907, Georgia became the first state to enact complete prohibition and five other states followed during the next two years. Five states went dry in 1914, four more in 1915, another nine in 1916, four more in 1917, and an additional eight in 1918.38

As successes piled up, the prohibition movement focused on passing a national law prohibiting the sale and distribution of alcohol throughout the nation. In 1895, the Anti-Saloon League had opened an office in Washington, D.C., with a mandate to lobby Congress to pass laws opposing the manufacture and sale of alcohol. Wheeler worked on and off with this lobbying group, applying the same tactics that he had developed at the state level to the national level. The group worked hard to elect representatives who would support their cause.

Eventually, the league and its allies decided that the time had come for Congress to pass prohibition legislation. By 1914, the movement had enough votes in the U.S. House of Representatives to guarantee that the Sheppard-Hobson Joint Resolution for National Prohibition Constitutional Amendment would make it out of committee, and enough power to ensure that it came to a vote. The Women’s Christian Temperance Union organized a national petition drive supporting the amendment, and by April 1914 it had collected the endorsements of more than 3 million Americans. When the amendment came up for a vote in the House in December 1914, 197 Congressmen voted in favor, 7 more than voted against it, but it was still far short of the required two-thirds majority.

Rather than give up, the Anti-Saloon League and its allies intensified their efforts, focusing specifically on the next congressional election cycle. Wheeler began working full-time on the national agenda; his first objective was to elect as many congressional supporters as possible in November 1916. Although that election saw victories for many prohibition candidates, there were still not enough to pass an amendment to the Constitution.

As soon as the United States declared war on Germany in April 1917, the Anti-Saloon League began lobbying for laws restricting the production of alcoholic beverages. On August 10, 1917, Congress did pass the Lever Food and Fuel Control Act, which banned the production of distilled spirits for the duration of the war, but this did not satisfy those supporting total prohibition. The U.S. Senate passed a national prohibition amendment—the Eighteenth Amendment—in August 1917, and the House did so in December of that year. Even before the Eighteenth Amendment was ratified by the states, Congress passed the Wartime Prohibition Act, which banned the sale of beverages having alcohol content greater than 2.75 percent. By January 1919, the requisite number of states had finally ratified the Eighteenth Amendment, and national Prohibition became the law of the land a year later.

Success and Failure

It took more than the pressure tactics of the Anti-Saloon League, a barrage of temperance propaganda, and war hysteria and patriotism to get the Eighteenth Amendment passed. Prohibition was just one measure advocated by a much broader progressive movement, which promoted reforms at the local, state, and federal levels from the 1890s until 1920. National progressive successes included the passage of other constitutional amendments: the income tax (1913), direct election of senators (1913), and women’s right to vote (1920).

Another factor that contributed to the success of Prohibition’s passage was a lack of cooperation within the alcoholic beverage industry. Brewers would not work with distillers; each viewed the other as competition. Brewers considered beer, which was fairly low in alcohol, to be a temperance beverage; they did not think it would ever be outlawed. There were also divisions within the brewing industry itself. National companies had interests different from those of small brewers serving only a locality or region. Big brewers thus did not oppose local and state bans on brewing because these laws effectively shut down their smaller competitors. Meanwhile, brewers believed that distillers supported closing saloons because distilled spirits could be sold legally in drugstores, whereas druggists did not sell beer.39

When the prohibition movement picked up steam in the early twentieth century, brewers, distillers, wholesalers, and retailers never formed a united front to combat its growing opponents, and they never developed much political or public support. Breweries bought or invested in newspapers in several cities and funded editorials in others, but these generated little support. The National Wholesale Liquor Dealers Association of America, which represented only a fraction of the nation’s distillers, wineries, and wholesalers, issued four anti-prohibition manuals beginning in 1915. Other anti-prohibition propaganda presented the liquor industry as a friend of the workingman—a characterization that Americans just did not buy.40 These efforts were too little, too ineffective, and too late.

Societal shifts that took place after the Civil War also contributed to the success of Prohibition. Prior to the war, the temperance movement was strongest in New England, followed by the Midwest. Southerners did not support the temperance bandwagon, partly because New Englanders supported the abolition of slavery. After the Civil War, however, the temperance movement took off in the South, in large part as a means of keeping alcohol out of the hands of African Americans.41 The southern temperance movement affiliated with the Ku Klux Klan, which was reinvigorated in 1915 after the release of the film Birth of a Nation and the proliferation of books and articles portraying blacks as aggressive drunks and merciless rapists. The Klan went after not just African Americans but also immigrants, such as the Irish, Italians, Germans, and Jews—many of whom were leaders in the distilling industry.42 Throughout Prohibition, the Klan supported enforcement efforts against minorities and immigrants. Where law enforcement was lax, the Klan was willing to take up the slack, especially in the rural South.43

Another factor in Prohibition’s success was the rapid industrialization that took place in the post–Civil War period, which required sober workers for the nation’s factories. The nation’s industrial elite, such as oil magnate John D. Rockefeller and automobile manufacturer Henry Ford, supported Prohibition as a means of guaranteeing a sober workforce. Rockefeller, a lifelong nondrinker and America’s wealthiest Baptist, strongly supported Prohibition; he donated 10 percent of the Anti-Saloon League’s total budget. Ford required that all his workers be teetotalers, and he hired undercover agents to make sure they stayed that way. Ford workers caught buying liquor a second time were fired. Other companies followed similar rules, and many refused to hire anyone who was known to drink. Industrialists also blamed alcohol for the worker unrest sweeping America in the early twentieth century, and they thus supported and financed prohibition groups, especially the Anti-Saloon League. Industrialists became even more interested in supporting prohibition when states passed workmen’s compensation laws, which required employers to pay workers for on-the-job accidents, even if the injuries were the fault of inebriated workers.44

The prohibition movement had figured out how to pressure legislators and had succeeded in the most difficult task of passing an amendment to the Constitution, but they had not bothered to gain support from mainstream Americans. Many Americans were moderately swayed by the propaganda machines of the temperance societies, but were not deeply committed to the cause. Others were upset by the tactics that had been used by the prohibition movement. Some believed that the majority of Americans would not have voted for prohibition had they been given the opportunity.

Even before Prohibition went into effect, organized opposition emerged. The Association Against Prohibition was organized in 1918, and it quickly picked up members as the economic costs became evident: hundreds of thousands of Americans were put out of work when breweries, wineries, distilleries, cider mills, and retail outlets closed. The officers of the brewer’s union wrote in 1920 that there was no analogy in the history of any nation “in which hundreds of thousands of men were deliberately deprived by the state and the nation of their employment and business, without a semblance of consideration of the wishes of the people.” Neither the prohibition movement nor the legislation they supported included provisions for unemployment insurance or compensation for the stockholders.45 Then there were the millions of Americans who liked to drink: when opportunities presented themselves, they were willing to violate the law.

But public opposition was minimal at first, and most Americans seemed resigned to not drinking when the law went into effect in January 1920. Americans did cut down on their drinking. Prohibition advocates claimed that workers were using the money they saved on alcohol to buy more food for their families, and grocery store sales did in fact increase during the early 1920s. One businessman reported that before Prohibition, absenteeism on the day after payday had been about 10 percent, but this dropped to just 3 percent after Prohibition took effect. Death rates associated with alcohol also dropped precipitously. Moreover, diseases connected with alcohol, such as cirrhosis of the liver, had declined in dry states before Prohibition, and they continued to decline during the years of national Prohibition. Hospitals treated fewer patients. Violent crime was down. Drunkenness was less common.46 It looked as if Prohibition would be a great success.

The major flaw in prohibition legislation was enforcement. The Eighteenth Amendment had given concurrent enforcement power to the federal and state governments; however, the federal government hired only 1,500 enforcement agents, and it was impossible for them to enforce the law throughout the United States. Meanwhile, local and state law enforcement officials were not always supportive of Prohibition, and many state and local agencies lacked the trained manpower to enforce it or to deal with the organized crime that emerged.

The Anti-Saloon League and other prohibition organizations had been very effective in passing the Eighteenth Amendment and accompanying legislation, but they had not been effective in mobilizing public support for it. Lack of widespread support outside of particular religious groups contributed to the willingness of many Americans to violate the law. Twenty months after Prohibition took effect, the Bureau of Internal Revenue estimated that Americans drank 25 million gallons of illegal liquor, and that bootlegging was already a $1 billion business—and this was before bootlegging began in earnest. Speakeasies (illegal establishments that served alcohol) soon replaced saloons. By 1922, there were an estimated 5,000 speakeasies in New York City alone. An extensive underground economy developed around illegal alcohol; rural moonshiners flourished, as did the urban makers of “bathtub gin.” Gin was the easiest alcoholic beverage to make; its harsh taste could be masked by juniper oil, which also increased volume and diluted the alcohol. When organized crime began centralizing the manufacture, distribution, and retail sales of liquor, wealth and power flowed to the crime syndicates. In addition, as Americans increasingly flouted Prohibition, a generation came of age with little respect for the law.47

Violation of Prohibition became more common. Advocates were convinced that most violators were foreigners, especially immigrants from Italy and Mexico. A bill was introduced into the House of Representatives that would deport violators of the Volstead Act who were not citizens. It passed with a wide margin in the House but was ignored by the Senate.48

Meanwhile, wealthier Americans never felt that Prohibition was intended for them, and members of the upper class never had a problem securing whatever beverages they wanted throughout the Prohibition era. Over time, the urban middle class also gained access to alcohol through speakeasies and other channels. It was only the working class that suffered the most during Prohibition. The main drink of working-class Americans—beer—was almost completely unobtainable: it was too difficult to brew, transport, and sell. Distilled spirits were more readily available in most cities and the business was more lucrative, but they were much more costly than pre-Prohibition prices and unaffordable for the working class.49

The liquor served in speakeasies was notorious. Prior to Prohibition, saloons, bars, and other drinking establishments served beer, wine, and whiskey purchased from commercial breweries, distilleries, and vintners, whose practices were regulated. The alcohol served in speakeasies, however, was usually made by amateurs: it occasionally contained poisons and frequently tasted terrible. Imported alcohol was available, but only at extremely high prices—and much of what was sold as imports was actually domestic bootleg liquor poured into fancy bottles with fake labels. Customers never knew where their drinks came from or what they were made from.

The Volstead Act permitted the production of industrial alcohol for various purposes, such as making antifreezes or lacquers, but required that such alcohol be “denatured” through the addition of a noxious substance, such as wood alcohol (methanol), benzene, formaldehyde, or sulfuric acid, to make it unpalatable or toxic. It was relatively easy to remove these substances, however. As soon as Prohibition went into effect, illegal operations popped up around the country to purchase industrial alcohol, convert it into drinkable form, and distribute it to speakeasies. The problem was that many engaged in this were not scientists, the process was not always successful, and people who drank the alcohol sometimes died or went blind. A report by the Bureau of Prohibition showed that 98 percent of the alcohol it confiscated contained poisons. Another report claimed that downing just three drinks made with improperly converted industrial alcohol could be fatal. In New York alone, an estimated 700 people died in a single year during Prohibition because of poisonous spirits. When Wayne Wheeler was asked about these deaths, he responded unsympathetically, “The person who drinks this industrial alcohol is a deliberate suicide.” He concluded that “to root out a bad habit costs many lives and long years of effort.”50

As violent crime increased, newspapers, magazines, radio programs, and newsreels in movie theaters kept Americans, even in rural areas, abreast of the latest murders, violence, arrests, and corruption associated with illegal alcohol. Partly as a result, Prohibition lost support, especially among America’s elite. Industrialists who had once supported Prohibition now opposed it, as did many political leaders. Without the financial support of the well-to-do, organizations such as the Anti-Saloon League had difficulty staying afloat. In addition, states and local communities slackened their enforcement efforts.

By 1930, authorities that estimated 250,000 speakeasies operated in the United States. The New York City police commissioner estimated that there were 32,000 speakeasies in that city alone—more than twice the number of legal bars and saloons that existed prior to Prohibition. Others said that the commissioner’s estimate was actually way too low—that there were at least 100,000 speakeasies in the city. Mabel Willebrandt, the U.S. assistant attorney general responsible for prosecuting violations of the Volstead Act, commented on the lawlessness in New York’s speakeasies: “It can not truthfully be said that prohibition enforcement has failed in New York. It has not yet been attempted.”51 As enforcement failed, Congress stepped in and passed the Jones Act, which greatly increased the penalties for violating the Volstead Act. The first conviction was a felony, with the maximum penalty increased to five years of imprisonment and a fine of $10,000. Even with harsh provisions, enforcement did not work.

The Jones Act alienated many prominent Americans, including William Randolph Hearst, owner of one of America’s largest newspaper chains. Opposition to Prohibition strengthened. In 1927, membership in the Association Against Prohibition had more than 750,000 members. Two years later Pauline Sabin, a wealthy and politically well-connected New York socialite, formed the Women’s Organization for National Prohibition Reform. In less than a year, it had more than 100,000 members; by 1931, its membership had reached 300,000; by November 1932, membership was more than 1.1 million.52

Despite growing opposition to the Volstead Act, the widespread disregard for its provisions, and the associated violent crime and corruption, the Eighteenth Amendment might not have been repealed had it not been for the Depression. Republicans had strongly associated themselves with Prohibition, whereas many Democrats—especially those who were Irish, Italian, Jewish, Catholic, and German—strongly opposed it. When the stock market crashed in 1929 and the economic system collapsed, the Republicans, who had controlled Congress since 1919 and the presidency since 1921, were blamed. In November 1932, President Herbert Hoover lost his reelection bid and the Democrats swept into power with large majorities in both houses of Congress. President Franklin Roosevelt pledged to get the economy moving again.

At the time, federal coffers were empty. With almost 25 percent of the American workforce unemployed, income tax revenue was down. Roosevelt and his allies presented repeal as a means of generating revenue. Reinstating the excise tax on the sale of liquor was thus one argument for ending Prohibition. Others argued that repeal would relaunch industries that had once employed hundreds of thousands of Americans. Still others believed that repeal would help put an end to the burgeoning crime generated by the illegal production and sale of alcohol. On February 20, 1933, the U.S. Congress proposed and approved the Twenty-First Amendment to the Constitution, which repealed Prohibition. The amendment was ratified by the last of the required number of states on December 5, 1933. The “noble experiment,” as it was called, was over. Throughout the country, countless toasts were raised to repeal.

Prohibitory Effects

Prohibition had lasting effects on what Americans drank. The sale of nonalcoholic beverages rose during Prohibition. Fruit juices (such as grape, orange, and lemon) were advertised as healthful, and their sales accelerated. The sale of fizzy soft drinks also increased, partly because sodas—such as ginger ale and Coca-Cola—became mixers for cocktails made with unpalatable bootleg hooch.53 When Prohibition ended, Americans continued to use sodas in many cocktails. Soda companies also introduced new products during Prohibition. The Chero-Cola Company, for instance, introduced its Nehi beverage line, with orange, grape, and root beer flavors. The product that would eventually become 7-Up was first marketed in 1929.

Most complicated prohibition cocktails devised to mask the taste of the alcohol disappeared after repeal. The bartender Patrick Gavin Duffy included formulas for Prohibition cocktails in his Official Mixer’s Manual (1934), but noted that he did so that future Americans could see “the follies which the enactment of the Eighteenth Amendment produced.” Dr. Charles Browne, a former member of Congress and author of The Gun Club Drink Book (1939), praised the cocktail’s “general return to reason.”54

A number of new and novel beverages appeared on the market during Prohibition, and many survived after repeal. Edwin Perkins, head of the Perkins Products Company of Hastings, Nebraska, marketed a bottled soft drink concentrate called Fruit Smack, which was intended to be combined with water and sugar. Fruit Smack was popular, but the heavy bottles were expensive to ship. Perkins tried a second idea—a powdered concentrate that could be sold in paper packets. Customers just had to dissolve the powder in water and add sugar. Perkins called his product Kool-Ade (later renamed Kool-Aid). This helped to create a new category of beverages—children’s drinks—that still flourishes.

Prohibition wrought changes in alcohol consumption as well. Hard cider, which had been in decline for decades before Prohibition, never recovered its popularity, although sales of nonalcoholic apple juice were strong during and after Prohibition. Prior to Prohibition, beer had been America’s second most popular beverage after water; before Prohibition, Americans drank an estimated 20.2 gallons per person annually. Beer consumption declined precipitously during Prohibition; it was difficult to brew beer undetected, and its low alcohol content made it less profitable than distilled spirits. Prohibition had converted many drinkers from beer to spirits. Following repeal, beer consumption dipped to 10.9 gallons per person, almost half what it had been before Prohibition.

Conversely, wine consumption skyrocketed during Prohibition. It was legal to make wine at home, and many Americans took up winemaking. Homemade wine filled a void, but with repeal, wine consumption plummeted as other alcoholic beverages became available again. To survive, many wineries produced the cheapest wines possible, which drove well-to-do Americans to seek out better-quality European imports.

The most important change wrought by Prohibition, however, was related to alcohol production. Many breweries, wineries, and distilleries did not survive the Prohibition era, and many of those that reopened in 1933 had a tough time regaining their footing because of the Depression. The brewing, distilling, and winemaking industries consolidated, and today a small number of corporations control a large percentage of their respective markets.

Prior to Prohibition, high-end restaurants made much of their profits from the sale of liquor that preceded, accompanied, and followed a meal. Prohibition sounded the death knell for most big-name restaurants, although a few—such as New York’s Twenty-One Club—hung on by selling good food and illegal alcohol and paying bribes to the police and city officials. However, soda fountains thrived during Prohibition, but disappeared shortly after repeal. By this time, the country was in the depths of the Depression, and soon restaurants would experience the rationing that took effect during World War II. It was not until after the war that high-end restaurants reemerged.

Postscript

Wayne B. Wheeler steadfastly supported Prohibition until his death in 1927, five years before repeal.

Wayne B. Wheeler steadfastly supported Prohibition until his death in 1927, five years before repeal. Despite the problems with the Eighteenth Amendment, Americans consumed less alcohol after Prohibition than they had before. Per capita consumption of alcohol would not return to pre-Prohibition levels until 1965.55

Despite the problems with the Eighteenth Amendment, Americans consumed less alcohol after Prohibition than they had before. Per capita consumption of alcohol would not return to pre-Prohibition levels until 1965.55 The Twenty-First Amendment repealed national Prohibition, but it did not contravene state or local temperance laws. Mississippi was the last state to repeal its prohibition law, in 1966.

The Twenty-First Amendment repealed national Prohibition, but it did not contravene state or local temperance laws. Mississippi was the last state to repeal its prohibition law, in 1966. While Prohibition ended eight decades ago, concern with alcoholic consumption has remained part of American life. Groups such as Alcoholics Anonymous, Mothers Against Drunk Driving, and Students Against Drunk Driving, and stricter enforcement of driving while under the influence of alcoholic beverages, have emerged to deal with some problems that caused Prohibition.

While Prohibition ended eight decades ago, concern with alcoholic consumption has remained part of American life. Groups such as Alcoholics Anonymous, Mothers Against Drunk Driving, and Students Against Drunk Driving, and stricter enforcement of driving while under the influence of alcoholic beverages, have emerged to deal with some problems that caused Prohibition.

Wayne B. Wheeler steadfastly supported Prohibition until his death in 1927, five years before repeal.

Wayne B. Wheeler steadfastly supported Prohibition until his death in 1927, five years before repeal. Despite the problems with the Eighteenth Amendment, Americans consumed less alcohol after Prohibition than they had before. Per capita consumption of alcohol would not return to pre-Prohibition levels until 1965.55

Despite the problems with the Eighteenth Amendment, Americans consumed less alcohol after Prohibition than they had before. Per capita consumption of alcohol would not return to pre-Prohibition levels until 1965.55 The Twenty-First Amendment repealed national Prohibition, but it did not contravene state or local temperance laws. Mississippi was the last state to repeal its prohibition law, in 1966.

The Twenty-First Amendment repealed national Prohibition, but it did not contravene state or local temperance laws. Mississippi was the last state to repeal its prohibition law, in 1966. While Prohibition ended eight decades ago, concern with alcoholic consumption has remained part of American life. Groups such as Alcoholics Anonymous, Mothers Against Drunk Driving, and Students Against Drunk Driving, and stricter enforcement of driving while under the influence of alcoholic beverages, have emerged to deal with some problems that caused Prohibition.

While Prohibition ended eight decades ago, concern with alcoholic consumption has remained part of American life. Groups such as Alcoholics Anonymous, Mothers Against Drunk Driving, and Students Against Drunk Driving, and stricter enforcement of driving while under the influence of alcoholic beverages, have emerged to deal with some problems that caused Prohibition.