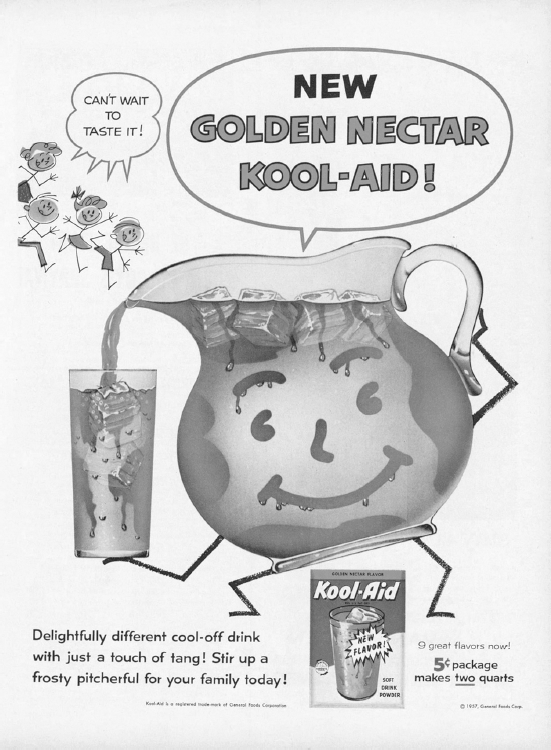

Advertisement for Kool-Aid (ca. 1950s). (Courtesy of The Advertising Archives)

IN 1920, Edwin Perkins—head of the Perkins Products Company of Hastings, Nebraska—marketed a new drink mix called Fruit Smack—a bottled syrup to be combined with water and sugar. The product did fairly well, but the heavy bottles were expensive to mail and they often broke in transit, dismaying customers and costing Perkins money to replace. In 1927, he came up with the ideal alternative: inspired by the tremendous success of Jell-O dessert powder, Perkins devised a powdered concentrate to be sold in paper packets. Customers still just had to add water and sugar, but with paper packets instead of bottles, they were much less likely to receive a soggy, drippy package when they ordered the product by mail. Perkins created six flavors—cherry, grape, lemon-lime, orange, raspberry, and strawberry—and sold the packets by mail for 10 cents apiece. He called the product Kool-Ade, which he trademarked in February 1928.

Not content to sell his product by mail, Perkins soon began a campaign to distribute Kool-Ade through grocery stores. It was promoted in newspapers, magazines, and on the radio—a very novel way to promote products at the time. The campaign brought Kool-Ade to the attention of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), which claimed that “-ade” meant “a drink made from.” Because most Kool-Ades were named after fruit, such as oranges, grapes, and lemons, this implied (according to the FDA) that it should be composed of fruit juice; however, Kool-Ade was artificially flavored and colored. The company renamed its product to Kool-Aid in 1934.

During the Depression, Perkins lowered the price of Kool-Aid to a nickel per packet and launched a national advertising campaign aimed at children. The company placed advertisements in children’s magazines; like promotions for other children’s products, Kool-Aid ads promised readers a gift, such as a pilot’s cap, in exchange for empty Kool-Aid packages.1

Kool-Aid dominated the children’s beverage market throughout the Depression. It was priced low for consumers and cost little to make, and the Kool-Aid flavors were loved by many children. During World War II, sugar was rationed, so Kool-Aid sales lagged; after the war, however, the product took off. By 1950, Perkins Products was cranking out 1 million packets of Kool-Aid a day. In 1953, Edwin Perkins sold the company to General Foods Corporation, which introduced the famous “Smiling Face Pitcher” advertising campaign for Kool-Aid in 1954.

Kool-Aid sales skyrocketed, which encouraged researchers at General Foods to experiment with variations on Kool-Aid. In 1957, they came up with an orange-flavored, powdered breakfast-drink mix fortified with vitamins. Sold in jars, the new product was released in 1959 under the brand name Tang. The mix might have disappeared quietly from the market if the National Aeronautic and Space Administration had not sent Tang on its Gemini space flights in 1962. Inextricably linked to the glamour of astronauts and space flight, Tang’s popularity soared. Kool-Aid and Tang are just two of thousands of beverages targeted at children, adolescents, and those younger than thirty years.

Background

Throughout much of early American history, children drank pretty much the same beverages as did their parents; alcoholic beverages served to children were sometimes, but not always, diluted. In New Orleans, for example, children were given watered-down wine. Ciderkin was a drink made specifically for children. It was made by adding water to pomace—the compressed apple mush left over from making cider—and then pressing it again.2 The problem with fruit juice was that it started fermenting as soon as it was made. The temperance movement encouraged the development of unfermented juices, and the scientific discoveries of Louis Pasteur helped juice makers produce nonalcoholic fruit beverages. Sales of nonalcoholic fruit beverages were limited until Prohibition took effect in 1920. Fruit juice producers—such as those making grape, grapefruit, lemon, and orange juice—launched advertising campaigns that touted the healthful effects of consuming juices, especially for children.

Other companies, such as the makers of Hi-C, Hawaiian Punch, and Delaware Punch, developed fruit-flavored drinks. Delaware Punch consisted of a variety of ingredients, prominently grape. It originated with Thomas E. Lyons in 1913. To market his noncarbonated beverage, he created the Delaware Punch Company of America in San Antonio, Texas. By 1925, the company was selling 172 million bottles per year, which was more than Coca-Cola at the time. The company’s early advertising targeted families, as well as “schools, on athletic fields and at social gatherings,” among other demographics.3

Beverages targeting youth increased after World War II as the so-called baby boom generation emerged. Hawaiian Punch originated in Fullerton, California, as an ice cream topping. A. W. Leo, Tom Yates, and Ralph Harrison converted it into a concentrate that was sold to local soda fountains. In 1946, the company was purchased by Reuben P. Hughes and others, who renamed it the Pacific Hawaiian Products Company. Hughes shifted from selling concentrate to soda fountains to selling concentrate to grocery stores. In 1950, Highs expanded a ready-to-serve red Hawaiian Punch in large forty-six-ounce cans.4 The company used cartoon characters, Punchy and his frequent target Opie, to advertise its fruit-flavored juice to children.5

Hi-C Enriched Orangeade—a fruit-flavored drink with 10 percent orange juice, sugar, and flavorings—originated with Niles Foster, a bottling plant owner, in 1946. It was marketed in 1948 through a massive promotional effort targeting children. One 1949 advertisement proclaimed that it was a “healthful drink the children begged for.” It quickly became the leading fruit drink in the children's market.6 In 1954, Hi-C was sold to Minute Maid, a subsidiary of the Coca-Cola Company. They extended the product line to include other fruit juices, such as apple and grape. Two years later, Minute Maid began advertising Hi-C on television. One advertisement espoused that Hi-C was “made from fresh fruit and naturally sweetened” and “was good for children.” In 1971, the Federal Trade Commission brought suit against the company for allegedly misleading advertisements. The lawsuit dragged on for two years, and finally Coca-Cola won the argument.7

Fruit juice had been bottled since the late nineteenth century, but usually in large family-size bottles for purchase in grocery stores. In 1972, three New York entrepreneurs launched a very small company called Unadulterated Food Products, Inc., in Brooklyn. It produced ready-to-drink fruit juices, sodas, and seltzers in wide-mouth bottles. The company sold its products to health-food stores, using a slogan of “made from the best stuff on earth.” It was so successful in its “new-age” marketing approach that sales surged. The company marketed other beverages, such as lemonade; in 1988, it launched flavored tea. In 1993, the company changed its name to the Snapple Beverage Company. It had fifty-five different products and sales were accelerating.

Snapple was so successful that it attracted competition. Pepsi created a partnership with Lipton to launch Pepsi Lipton Teas in 1991. The Coca-Cola Company jumped in as well: in 1994, it launched a line of fruit drinks called Fruitopia. Coca-Cola’s first juices were Born Raspberry, Peaceable Peach, Lemon Berry Intuition, and Curious Mango. It targeted teens and young adults. Fruitopia sales increased initially but then declined, and Fruitopia was discontinued.8

Snapple was purchased by the Quaker Oats Company for $1.7 billion in 1994. Quaker also owned Gatorade, and the company concluded that it could sell both products to youth in a similar manner. Quaker quickly found that Snapple could not be sold in the same way as Gatorade: although they were both targeted at youth, one was a sports drink and the other was a health drink. At the same time, new competing products came on the market—AriZona Iced Tea, Nantucket Nectars, and Mystic—and Snapple sales declined. Quaker sold Snapple twenty-nine months after acquiring it for $700 million to Triarc.9 Snapple recovered, and Triarc sold the division to Cadbury Schweppes in 2000. Cadbury and Schweppes demerged in 2008, and a new beverage company, Dr Pepper Snapple Group, was formed in North America.

Snapple consistently marketed its beverages as healthy alternatives to soft drinks. In September 2003, New York banned the sale of candy, soft drinks, and other sugary snacks at its schools. City officials selected Snapple as the official beverage of the city. As part of the $166 million agreement, Snapple acquired exclusive rights to sell its beverages in the city’s 1,225 public schools. Critics pointed out that many Snapple beverages contained more calories than soft drinks. Michael Jacobson, executive director of the Center for Science in the Public Interest, complained that “the new Snapple drinks are a little better than vitamin-fortified sugar water because the juices may provide low levels of some additional nutrients.”10

By far the most important children’s beverage was—and continues to be—milk. During the nineteenth century, breastfeeding declined in America. Despite concerns about the safety of milk, it was a necessary beverage for children. By the early twentieth century, the dairy industry problems declined and nutritionists praised milk as the “perfect food,” especially for children. The dairy industry saw this as an opportunity to promote the health benefits of milk, and advertisements pictured robust, happy children thriving on pure, nutritious milk.11 The ads emphasized milk’s fortification with vitamin D (that began in the 1930s)—something that made it even more important for children.

As milk sales soared, entrepreneurs started to develop products that could flavor milk in ways that appealed more to children. In 1926, Hershey’s Chocolate Syrup was introduced at soda fountains for use on ice cream as well as an additive to beverages; two years later, the retail version of the syrup went on sale. Meanwhile, the William S. Scull Company of Camden, New Jersey, which specialized in coffee and tea, introduced a product in 1928 called Bosco Chocolate Syrup. It was marketed as a sauce for ice cream and cake, as well as a “milk amplifier.” During the early 1930s, the company promoted Bosco as a milk amplifier and thus a health-giving children’s beverage. Bosco was soon enriched with iron, which was another important promotional point. The syrup’s advertisements proclaimed that “Dr. Philip B. Hawk has proved the unique bodybuilding qualities of Bosco.”12 Other companies began producing similar products. In 1939, the Taylor-Reed Corporation of Mamaroneck, New York, began manufacturing Cocoa-Marsh, a “milk amplifier” that was advertised as a chocolate syrup that made “milk haters, milk lovers.”13

Milk “modifiers” also came in powdered form, like the malt powder used at soda fountains. Ovaltine, a Swiss product created by a physician in 1904 to nourish seriously ill patients, was first marketed in the United States in 1905. A sweetened, malted chocolate powder to be mixed with milk and drunk hot or cold, Ovaltine sponsored some of the most popular American radio shows of the 1930s and 1940s; its healthful qualities, particularly five vitamins (protein, iron, niacin, calcium, and phosphorus) were always touted in its advertising. Nestlé Quik (now called Nesquik) was another chocolate drink powder; introduced in 1948, its long sponsorship of children’s television programming ensured its lasting popularity.

Yet another milk-related beverage that appealed to young people was the milkshake. By the late nineteenth century, soda fountains offered a drink concocted from milk, flavorings, and ice cream that were shaken up vigorously to make a thick, smooth mixture. With the invention of a practical electric blender by Hamilton Beach in 1910, milkshakes became popular, particularly during Prohibition.14 The malt shop became a feature of small-town Main Streets throughout America. Fast food restaurants put milkshakes on their menus in the 1930s, although some chains discontinued them after discovering that the shakes took too long to make and ruined customers’ appetites for hamburgers.

The invention of the Multimixer by Earl Prince in 1936 permitted several milkshakes to be made simultaneously. Salesman Ray Kroc was so impressed with the invention that he purchased the rights to the machine in 1939. After World War II, the Multimixer was sold to ice cream chains such as Tastee-Freez and Dairy Queen. Because of stiff competition, sales of Multimixers declined in the early 1950s. At that time, Kroc noted that two West Coast entrepreneurs, Richard and Maurice McDonald, had purchased eight Multimixers. Kroc visited the McDonalds’ new hamburger stand, which was located in San Bernardino, California, and discovered that every morning the staff prepared 80 milkshakes and stored them in the freezer, ready to serve. If the supply ran out during the day, the staff made more shakes. The McDonald brothers were selling an astounding 20,000 milkshakes per month. The visit ended with Ray Kroc acquiring the rights to franchise McDonald’s nationwide.15

Since the 1950s, shakes have been offered regularly at most fast food operations; some chains have created their own versions, such as Wendy’s Frosty, made with milk, sugar, cream, and flavorings. Today, the thickness of a fast food milkshake is likely created by ingredients such as microcrystalline cellulose rather than rich ice cream; moreover, shakes and similar treats have received considerable criticism because of their high calorie and fat content.

Smoothies are blended drinks inspired by milkshakes, but sometimes they contain no dairy products. These nonalcoholic cold beverages include a mixture of healthful (or purportedly healthful) ingredients, such as fruit, fruit juice, ice, yogurt, milk, and occasionally ice cream. When smoothies first appeared in the 1960s, they were usually blends of fresh fruit and yogurt, typically dispensed in health-food stores. Composed of fresh ingredients, smoothies are usually made to order. They began to be sold outside of health-food stores in the early 1970s.

In the 1960s, a Louisiana teenager named Steve Kuhnau worked as a soda jerk, mixing up malts, shakes, and sodas. Ironically, Kuhnau suffered from lactose intolerance and was unable to sample many of his creations. He began experimenting at home with nutritional drinks, blending fruit, nutrients, vitamins, minerals, and protein powders. In 1973, Kuhnau opened a health-food store in Kenner, Louisiana, where he began selling the beverages, which he called smoothies. The drinks proved popular, so Kuhnau perfected the recipes and, in 1989, franchised the operation as Smoothie King. The company now has more than 550 locations in the United States, with a menu offering dozens of different combinations of smoothies and snacks.

Once Kuhnau’s success became evident, various competitors surfaced. Kirk Perron opened his first smoothie store, called the Juice Club, in San Luis Obispo, California, in 1990. Five years later, the company changed its name to Jamba Juice. It featured all-natural foods, such as made-to-order fruit smoothies, fresh-squeezed juices, healthy soups, and baked goods. Jamba Juice expanded by acquiring a smaller chain, Zuka Juice, in 1999.16

As of 2010, an estimated 3,000 juice bars throughout the United States sold smoothies, as did tens of thousands of smoothie outlets, including Dairy Queen, Froots, and Tropical Smoothie Café. In 2010, McDonald’s also began selling smoothies, much to the consternation of the more specialized drink chains.

Sports and Energy Drinks

Sports drinks are designed to enhance athletic performance by fostering endurance and recovery. The first such beverage was Gatorade, which was formulated in 1965 by Robert Cade and Dana Shires of the University of Florida to solve rehydration problems faced by the school’s football team, called the Gators. Gatorade is a noncarbonated drink that consists of water, carbohydrates (in this case, sugar), and electrolytes (sodium and other minerals vital for muscle function and fluid balance). Gatorade was used by the team in 1967, when the Gators won the Orange Bowl. This gave the drink extensive national visibility, and Gatorade soon commercialized.17

Intended for athletes participating in serious competition or intense exercise, sports drinks promote rehydration (the sweetness makes it easy to drink lots of liquid), replace electrolytes, and increase energy levels (as would any sugar-sweetened drink). Most people, however, do not work up enough of a sweat to need electrolyte replenishment, and chugging a sports drink while exercising can cause cramps.

Gatorade launched the sports beverage industry. Coca-Cola introduced Powerade in 1990, and since then the company has introduced various new flavors and formulas. In 1992, PepsiCo created the All Sport athletic drinks, promoted as the “Official Sport Drink” of the top soccer leagues. However, neither Powerade nor All Sport was able to challenge the success of Gatorade, which has remained the dominant sports drink on the market. In 1967, Stokely-Van Camp of Indianapolis secured the rights to Gatorade and marketed it nationally. Thirteen years later, Stokely-Van Camp was acquired by Quaker Oats, which was acquired by PepsiCo in 2003.18

The success of sports drinks encouraged the introduction of energy drinks, such as the ones developed by an Austrian named Dietrich Mateschitz, as a salesman for Blendax, a cosmetic firm. The company was acquired by Procter & Gamble, and Mateschitz’s job focused on selling the company’s toothpaste in other countries. His travels took him to Thailand, where he noticed that pharmacists sold low-cost energy tonics, such as Krating Daeng (Thai for “red water buffalo”), to factory workers who wanted to work a second shift and drivers who stopped at service stations. He tasted a variety of energy drinks in Asia, and he liked what he tasted. He also believed there was a market for these beverages in Europe. He resigned from Blendax, formed his own company in Austria, and with a partner introduced a nonalcoholic carbonated energy drink called Red Bull to Europe in 1987.19

Mateschitz was not the first to market energy drinks in Europe. An English pharmaceutical company developed the first energy drink, called Glucozade, in 1927. It was a fizzy liquid filled with sugar, mainly used to help children recover from illness. A British pharmaceutical picked up the formula, renamed it Lucozade, and promoted it with the slogan “Lucozade aids recovery.” In 1983, the company decided to reposition the product as an energy drink using the slogan, “Lucozade replaces lost energy.” It was rebranded as an energy drink for those engaged in sports, and Olympic athletes were hired to promote the product. Within five years, sales tripled.

A Japanese company, Tashio Pharmaceuticals, popularized an energy drink called Lipovitan in 1962. The drink was so successful that the company was one of Japan’s top corporations within twenty years. It is likely that Mateschitz was aware of these successes before he launched his own business with Red Bull.20

Red Bull was introduced into the United States in 1997; it became America’s first popular energy drink. Each 8.3-ounce can supplied 80 milligrams of caffeine—about the same as a strong cup of coffee—as well as taurine (an amino acid) and glucuronolactone, a chemical that supposedly detoxifies the body. Red Bull started a frenzy of copycat beverages, such as Jolt, Monster Energy, No Fear, Rockstar, Full Throttle, and myriad other brands. Large companies jumped in, with Anheuser-Busch’s 180, Coca-Cola’s KMX, Del Monte Foods’s Bloom Energy, and PepsiCo’s Adrenaline Rush, SoBe, and Amp brands. These drinks boast caffeine levels up to 500 mg per 16 ounces, and they are often loaded with various forms of sugar. By the early twenty-first century, there were more than 300 energy drinks on the American market. Many include caffeine combined with other substances such as guarana, ginseng, and ginkgo biloba.21 Unlike sports drinks, which hydrate the body to replace fluid lost during exercise, the caffeine in energy drinks dehydrate the body.

Red Bull’s prime consumers were young adults (eighteen to thirty-four years old), particularly college students and young men who considered it to be a performance enhancer.22 Red Bull controls about 40 percent of the energy beverage market in the United States. In 2004, the most important energy drinks in the United States were Rockstar International and Coca-Cola Full Throttle and Tab brands. Energy drink consumption increased at an annual rate of 55 percent per year, according to Packaged Facts. They estimated that, in 2006, the U.S. market for energy drinks totaled $5.4 billion. Americans drink 3.8 quarts per person annually, according to Zenith International.23

The percentage of adolescents and young adults who consume energy drinks increased markedly between 2001 and 2008. The effects of these drinks on children and teens have not been well studied, but some health professionals cite a number of potential dangers, including heart palpitations, seizures, and cardiac arrest, among others.24

Red Bull and other energy drinks were often used as mixers for alcoholic beverages. Then, in 2000, Agwa, a beverage made from spent coca leaves that combined caffeine and alcohol, was introduced into America. Other companies began producing caffeinated alcoholic beverages. Within two years, the two leading brands of caffeinated alcoholic beverages sold 337,500 gallons. By 2008, sales reached 22,905,000 gallons, and they continued to increase ever since.25 A major reason for their success has been their heavy marketing to youth.26 Warnings about the consumption of alcohol and caffeine have proliferated and some countries have banned caffeinated alcoholic beverages. Today, more than 25 brands of caffeinated alcoholic beverages are sold in a variety of U.S. retail alcohol outlets, including many convenience stores.27

Today, beverages that particularly target teenagers and young adults are rapidly expanding. Supermarkets, grocery stores, convenience stores, and fast-food chains sell thousands of beverages that cater to these demographics. The diversity of these beverages has been rapidly increasing along with sales, and they likely will continue to increase in the future.

Postscript

The Hastings Museum of Natural and Cultural History has a permanent exhibit on Kool-Aid and its inventor, Edwin Perkins, who died in 1961.

The Hastings Museum of Natural and Cultural History has a permanent exhibit on Kool-Aid and its inventor, Edwin Perkins, who died in 1961. Thomas E. Lyons, the founder of Delaware Punch, died in 1951. His company was acquired by the Coca-Cola Company.

Thomas E. Lyons, the founder of Delaware Punch, died in 1951. His company was acquired by the Coca-Cola Company. Dietrich Mateschitz remains as the chief operating officer of the company that manufactures Red Bull. He is a multibillionaire.

Dietrich Mateschitz remains as the chief operating officer of the company that manufactures Red Bull. He is a multibillionaire. As of 2010, Jamba Juice had about 800 outlets in thirty states and was the leading chain in the field. Jamba Juice is headquartered in Emeryville, California.

As of 2010, Jamba Juice had about 800 outlets in thirty states and was the leading chain in the field. Jamba Juice is headquartered in Emeryville, California.

The Hastings Museum of Natural and Cultural History has a permanent exhibit on Kool-Aid and its inventor, Edwin Perkins, who died in 1961.

The Hastings Museum of Natural and Cultural History has a permanent exhibit on Kool-Aid and its inventor, Edwin Perkins, who died in 1961. Thomas E. Lyons, the founder of Delaware Punch, died in 1951. His company was acquired by the Coca-Cola Company.

Thomas E. Lyons, the founder of Delaware Punch, died in 1951. His company was acquired by the Coca-Cola Company. Dietrich Mateschitz remains as the chief operating officer of the company that manufactures Red Bull. He is a multibillionaire.

Dietrich Mateschitz remains as the chief operating officer of the company that manufactures Red Bull. He is a multibillionaire.