1

Truth is never ugly, when you find in it what you need.

— Edgar Degas

I have locked away my heart in a pink satin slipper.

— Edgar Degas

HER NAME WAS MARIE GENEVIÈVE VAN GOETHEM. Her parents were Belgian. They had emigrated to Paris to escape poverty like so many of their countrymen — and so many others from Italy and Poland — and had settled at the foot of Montmartre in one of the poorest neighborhoods in the city. Her mother was a laundress, her father a tailor. Marie was born in Paris on June 7, 1865, the second of three sisters. The eldest, Antoinette, had been born in Brussels in 1861 and posed for Degas first, starting at age twelve. She went on to become a prostitute and, driven by hunger, a petty thief, working alone or with her mother, and she eventually served time in the Saint-Lazare prison for women. The youngest, Louise-Joséphine, joined the Paris Opera as a “little rat” at the same time as Marie. Of the three, she had the least tragic life: she was selected for the corps de ballet and later became a successful dance teacher — one of her pupils was the great Yvette Chauviré. It’s always intriguing with siblings to see how fate works different embroideries on the same canvas of sufferings. The youngest, less brutalized by their aging mother, perhaps had the advantage of a more moderate temperament, or else loved dance sufficiently to carve a place for herself in that world, turning a constraint imposed by her mother into an avenue of salvation.

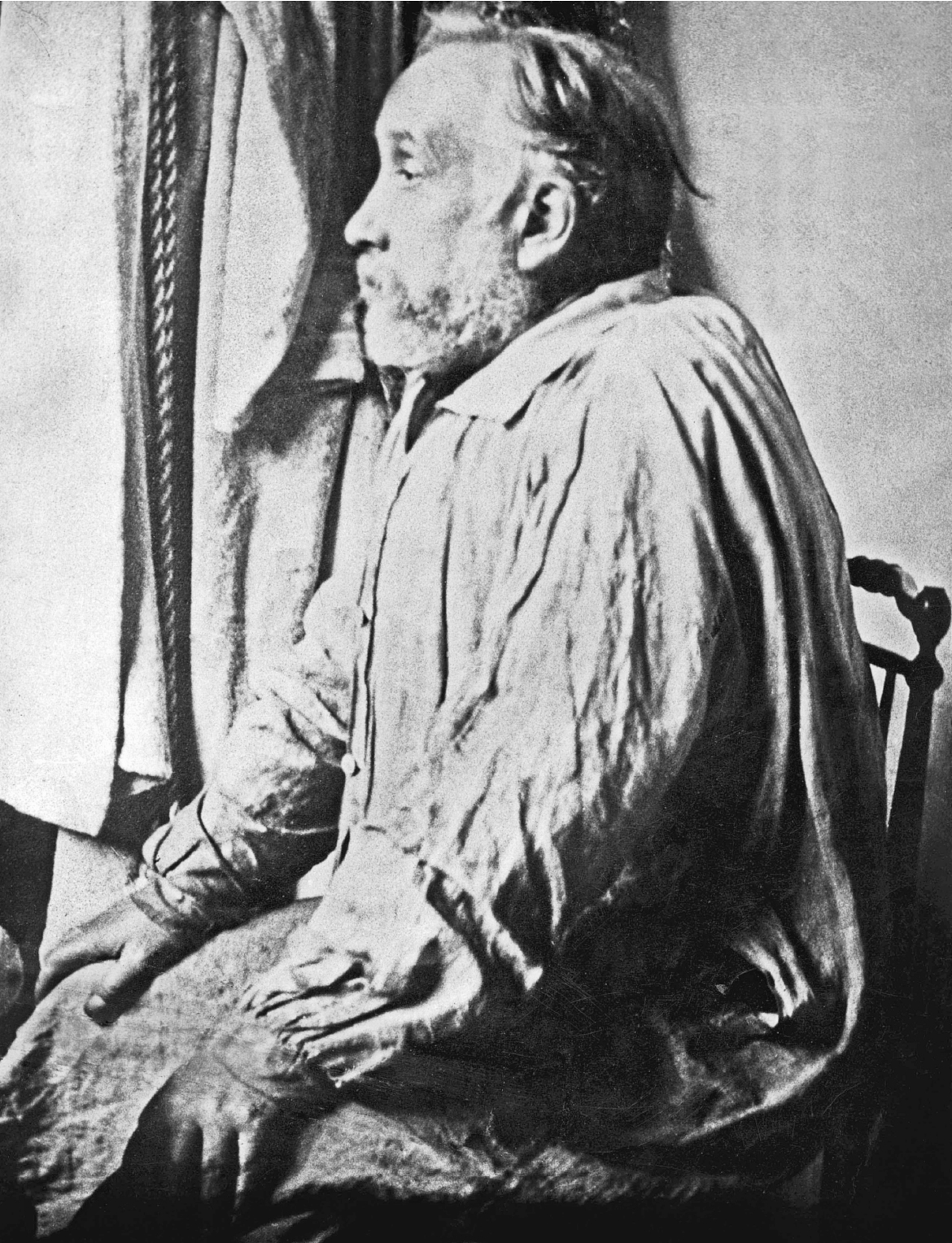

Degas might have met the sisters — or their mother — around the Paris neighborhood where they lived. During the twenty years from 1862, when they arrived in Paris, to 1882, when we mostly lose track of them, the Van Goethem family was registered at seven different addresses, always in the Ninth Arrondissement, near the place Pigalle. These successive moves likely reflect that they were skipping out on their rent after missing several payments in a row and finding the landlord increasingly insistent or else that they were trying to escape charges of prostitution. Degas also relocated several times while staying in the same general area — rue Blanche, rue Pigalle, rue Fontaine, rue Ballu, and boulevard de Clichy, where he lies buried today, in the Montmartre Cemetery. That part of Paris was also where the greater part of bohemia lived, alongside workers, shopkeepers, and employees — a stratum of society known in French as la blouse, for the loose-fitting smock its members often wore at work. Degas felt comfortable there, and often wore the smock himself, as did many painters, and was photographed in it. But he wasn’t poor, he didn’t live in a garret, and he didn’t lead the bohemian life immortalized in the opera by Puccini and the biopics about Modigliani. He was a well-off and somewhat conservative bourgeois who, at the start of the 1880s, occupied the fifth floor of a new apartment building and rented a handsome studio in the courtyard. His family took pride in belonging to the petty nobility, but he had altered his name from “de Gas” to the more plebeian “Degas,” which even became, in the phonetic rendering of the visitors’ register to the backstage of the Opera, “Degasse.” The replacement of the noble particle de by a vulgar prefix did not strike him as a loss of status. When the concierge at the Paris Opera, not knowing who was who, made fun of the top-hatted toffs who came to visit the young girls, he would have rhymed “Degasse” with radasse and pouffiasse, two slang words for women of low morals that were then gaining currency in bohemian Paris.

Yet at the point when Antoinette van Goethem and then Marie began posing for him in the mid-1870s, Degas — despite his early fascination with dancers and singers, whom he went to see regularly, and despite his reputation as, in Manet’s words, “the painter of dancers” — had not yet received permission to wander freely in the backstage area of the new Paris Opera. The old Opera building on the rue Le Peletier had been destroyed by fire, the Palais Garnier had just been inaugurated, and the pass that would allow Degas free entry via the service door to attend rehearsals would only be granted him in 1885, in return for his buying a subscription for three shows a week. In 1882, requesting access to the rehearsal space to attend a dance examination, Degas wrote, “I’ve painted so many of these examinations without ever having seen one that I’m a little embarrassed.”1 He may have insisted that the main part of painting was performed “by memory,” but he still needed time in front of the subject2 and often hired models to pose for him at his studio, sessions that produced a profusion of sketches and studies.

Until about 1880, he had essentially been a painter. But in the past few years, his eyesight had started to fail. Already in 1870, when he joined the infantry during the siege of Paris, he had noticed that he couldn’t see the target with his right eye. A long spell in a cold, damp attic had apparently damaged his eyesight irreversibly. He was barely forty years old, but already he was half blind. Highly sensitive to light, he was easily recognized around the capital by his blue-tinted eyeglasses. For a painter, this was a cruel fate. “Sculpture,” he explained to the gallerist Ambroise Vollard, “is a blind man’s trade.”3 From being a desire, it became a necessity. His hand would henceforth function as “an additional eye,”4 the sureness of his touch would make up for the growing inaccuracy of his vision. But Degas’s turn toward sculpture was not simply a response to circumstances. It also corresponded to his search for greater truthfulness: “I realized that for an exactness so perfect that it gives the sense of life, one has to resort to three dimensions.”5 Since his primary objective was — as in his paintings — to capture pure movement, wax became his preferred medium. He could model it easily and indefinitely, while marble or granite, materials destined “for eternity,” did not allow “the hand to approach the idea.”6 And wax was the substance that most closely imitated flesh.

MARIE VAN GOETHEM, the mother of Marie Geneviève, was a laundress, just as in a Zola novel — or rather, the reverse, since the author of L’Assommoir and Nana would admit to Degas that in certain passages he had “quite simply described” Degas’s paintings.7 Van Goethem mère led a hard life, slaving for pennies. The father, Antoine, was long gone, either dead or returned to Belgium. Life expectancy in the lower-class neighborhoods barely reached forty. Absinthe often cut lives short.

Having three daughters was both a plague and a boon to someone without money. You could always sell them. Childhood was not a defined sociological category in the nineteenth century, nor did it benefit from legal protection, and children could be exploited to differing degrees. The first recourse was to set them to work at something perfectly legal. This Marie van Goethem did in pushing her daughters to join the Paris Opera. She no doubt negotiated a group contract: sets of sisters were quite common. This was not the same as a mother enrolling her daughters in a ballet class, or even getting them an audition to see if they had talent. Rather, it was a terse bargaining session, leading to an employment contract that the mother would sign with an unsteady scrawl or a cross. The Jules Ferry Laws of 1881 and 1882, which would make primary education free and publicly available and later compulsory for all children ages six to thirteen, had not yet been enacted. The Paris Opera, in any case, would be exempted from those laws, and primary school would only become mandatory for the young girls at the Opera in 1919. The writer Théophile Gautier wrote an incisive but little-known text on this subject, “Le rat” (The Rat). In it, he bemoaned the total ignorance of these “poor little girls” who barely knew how to read and who “would do better to write with their feet, which are more highly trained and more adept than their hands.”8 These deprived girls never received any formal schooling and were obliged to earn, if not their living, at least their board. The majority had never known their father and provided the main support for their families. Boys could rent out their arms to work in the mines or on the farm; girls rented out their legs, their bodies. The Paris Opera recruited “little rats” as young as six years old. These would later come to be called marcheuses, “walkers,” because they spent all their time performing steps, first in the dance class, then onstage, where they would make their first appearance at thirteen or fourteen — Marie would make her walk-on debut in La Korrigane, a ballet in two acts. Théophile Gautier was quick to make fun of the nickname “walkers,” which suggested the profession the adolescents would soon adopt on the city’s sidewalks. The beginners earned two francs per day, a very small sum, but still twice what a miner or a textile worker was paid. Parisians had not forgotten that only a few years earlier, during the winter of 1870, when the capital was under siege by the Prussians, two francs was the price of a rat, a real rat — a cat would cost eight francs, while the elephant and the camel slaughtered at the Jardin des Plantes cost several months’ salary, a luxury only the rich could afford.

Opportunities for advancement at the Paris Opera, both social and economic, were real but also rare, and subject to biannual examinations that were both costly and difficult. For her performance before a jury, a dancer had to buy her tarlatan skirt, her silk ribbons, and the artificial flowers in her hair. Over the years, the more talented students rose through the ranks and received better pay; each public performance earned them a small bonus, which was added to their meager salary. If they passed the exam, they moved up from the dance school to the corps de ballet, then to the rank of featured dancer. Only at that point would they sign a firm contract, usually for fifteen years. Of the rats, only a minuscule number earned fame. Every mother dreamed of glory for her daughter, but most had more pragmatic goals. They were often widows or single mothers from working-class backgrounds, and they bombarded the director of the Paris Opera with pathetic letters (dictated, of course), pleading for “protection” for their daughters — no one was in any doubt what sort of protection a man might offer a woman. An auxiliary source of income was therefore available to the little Opera rat, and the practice was tolerated if not explicitly endorsed. What would be denounced today as pedophilia, pimping, and the corruption of minors was at the time normal practice, when “the prevailing moral code was a total lack of moral code.”9 Besides, children reached sexual majority at the age of thirteen, according to an 1863 law — the age had previously been eleven. Backstage, procurement was the quasi-official function of a mother, who was expected to “present” her daughter to male admirers. The police shut their eyes to it, as did the Opera administration. Those who reserved seats in the orchestra or private boxes in the balconies, the “subscribers,” had the free run of the foyer, the backstage area, and the private drawing rooms, which became trysting sites. Others, less fortunate and unable to obtain the privilege, waited in the hallways, the vestibules, and at the exit. “I adore the dancers’ mothers,” said the librettist Ludovic Halévy. “One always learns something from them…They have entry into every world. During the daytime they are fruit sellers, seamstresses, and washerwomen, but at night they chat familiarly at the Opera with our most eminent men.”10 It is entirely likely that Marie’s mother played the role of procuress and agent for her daughters. Shortly before Marie left the Opera, there was mention in L’Évènement, a newspaper that carried gossip about the world of dance, of “Mademoiselle Van Goeuthen [sic], fifteen years old. Has a sister who is a walk-on and another at the ballet school. Poses for painters.”11 The reporter adds that Marie frequented the cafés around Montmartre and ends: “Her mother…No, I can’t go on…I would say things that would make you blush — or cry.” Perhaps the mother also prostituted herself, but it seems certain at least that she, like many others, encouraged her daughters at a very young age to find a rich protector. Balzac, in the following scene about a man from the provinces freshly arrived in Paris, offers a prototypically Parisian tale:

“Well, well,” he said, pointing his cane at a pair of figures emerging from the alley by the Paris Opera.

“What is it?” Gazonal asked.

“It” was an old woman in a hat that had aged six months on a store shelf, a pretentious dress, and a faded tartan shawl, whose face showed the ravages of twenty years in a damp lodging, and whose bulging market bag announced a social position no better than ex-doorkeeper; beside her was a slender, willowy young girl, whose black-lashed eyes had lost their innocence, whose complexion spoke of great fatigue, but whose face, prettily shaped, was fresh, surrounded by a mass of hair, her forehead charming and bold, her chest flat — in a word, an unripe fruit.

“That,” said Bixiou, “is a rat, accompanied by its mother.”

“A rat?”

“This rat, just released from her rehearsal at the Opera, is returning home to a meager dinner and will be back in three hours to put on her costume, if she’s dancing tonight, because today is Monday. This rat is thirteen years old, already ancient. Two years from now, this creature will be worth 60,000 francs on the public square. She will be nothing or everything, a great dancer or a marcheuse, a famous celebrity or a vulgar courtesan. She has worked since the age of eight. As you can see, she is crushed with fatigue, having worn out her body this morning in dance class, and she is emerging from a rehearsal where the sequences are as hard as the moves in a Chinese puzzle. But she’ll be back again tonight. The rat is one of the constituent elements of the Opera. She is to the prima ballerina as a clerk is to a lawyer. The rat is hope.”

“Who produces rats?” asked Gazonal.

“Porters, actors, dancers, the poor,” said Bixiou. “Only the most desperate poverty could convince a child of eight to consign her feet and her joints to such severe torture, to stay obedient until the age of sixteen or eighteen, entirely on speculation, and to have always at her side a ghastly old crone, the way you might encircle a lovely flower with manure.”12

In branding the foyer of the Opera as a prime locus for licentiousness, Théophile Gautier went even further, describing the sexual trafficking, the “lurid nights of evil and orgies,” for which mothers gave their daughters “lessons in suggestive glances” before selling them. “Not all the slave markets are in Turkey,” he noted.13

MARIE VAN GOETHEM, then, joined the Paris Opera. The terms of the contract for such a spindly girl would have been harsh. She worked ten or twelve hours a day, six days out of seven, going from ballet class to rehearsals to performances. The 1841 law setting a limit on the length of a child’s workday did not apply to the Opera. The ballet school stipulated in its regulations that a student must absolutely live within two kilometers of the Palais Garnier, because the daily stipend of two francs would not cover the cost of a tram or omnibus: Marie came on foot every day — and it is likely that she never ventured beyond her neighborhood during her childhood. The director was all-powerful, and the least absence was a pretext for fines, culminating in dismissal — which required the guilty party to repay one hundred francs for each unfulfilled year of her contract. This is what happened to Marie, who was fired for absenteeism before her contract expired — but how could she ever find so much money in one place? It was just to make a little extra money that she had missed her classes in the first place.

Her daily life was one of hardship. She arrived at the Opera early in the morning and spent hours in class and at rehearsal, under the vigilant eye of despotic teachers: Mérante, the ballet master, who was known for his sadism, and the much-feared Monsieur Pluque. Marie was small and slight, the exercises exhausted her. The first order was to limber up at the barre, then to move out onto the parquet floor, regularly sprinkled with water, and string together the same movements: jetées, pirouettes, entrechats, ronds de jambe, fouettés, steps en pointe… She tired easily, not least because the food she ate was insufficient and of poor quality — and sometimes lacking altogether. She was threatened with having her legs and her back encased, as in the old days, in a sort of wooden box that was intended to correct faulty positions. She was forbidden to complain, to speak, to laugh, to cry. The musical accompaniment — played on the piano or the violin — and the breaks between sessions offered small crumbs of consolation over the course of a strenuous day. Chatting, laziness, and ill humor were infractions that received prompt punishment. When Marie’s mother attended class, sitting on a bench with the other biddies — she found occasional work at the Opera as a dresser — it was even worse, because scoldings then rained down on Marie from all sides. Her corset and tutu were worn, her hand-me-down cotton slippers were misshapen and had been repaired twenty times already. Her feet were often bloody and her poorly tended sores infected. When she arrived home at the tiny apartment she shared with her family, there was no running water. She couldn’t wash her sweaty body until the concierge saw fit to bring water, unless she went back downstairs herself, got in line at the water pump, and lugged the bucket back to the apartment without spilling. The public baths were expensive, and she could barely afford them once a month.

Did she have friends and playmates, as other children do? Sisters in misery, more like. Apart from a few girls of the French or foreign bourgeoisie who were grudgingly allowed by their parents to live out their love of ballet in this celebrated but highly suspect world, most of the Opera rats were driven to the work by necessity. Girls who weren’t admitted to the corps de ballet worked as walk-ons for a few centimes — the eldest, Antoinette, did this on several occasions. If they had no “protector” among the male subscribers to the ballet, because of not being especially pretty or skilled at gallantries, they suffered the worst privations and lacked even the funds to pay the dentist or the doctor when they were ill. Some came to a bad end — the story of Emma Livry was told in hushed tones, the girl who burned to death during a performance when her tutu caught fire from a gas burner in the wings. A number of girls, though barely fifteen years old, were already alcoholics — it was tempting to get tipsy milling with the crowd in the Opera’s foyer. Others died of tuberculosis. The class for the youngest girls was still fairly joyous and unrestrained, but as soon as the girls reached adolescence they acquired a blank gaze and a look of resignation, entering a life of prostitution without ever having been children. “The Opera rat is caught in the gigantic mousetrap of the theater at such an early age that she has no time to learn about human life,” wrote Théophile Gautier.14 A few, true enough, pursued their vocation assiduously and became great dancers, Marie Taglioni among them, whom Degas painted and even celebrated in verse. And if a subscriber took an interest, paying for a girl’s private lessons, a little rat might rise above her condition. It happened with Berthe Bernay, who joined the Paris Opera a short time before Marie van Goethem at six hundred francs a year and who, thanks to hard work, ended up a star with an annual salary of 6,800 francs. Others with less talent but endowed with grace made a career as courtesans of the demimonde and lived in luxury. And others yet, like Marie’s younger sister, retired from the stage after they reached thirty and became ballet masters. But all the rest, the great majority, were never more than little rats, swarming here and there in an unhealthy environment. Their nickname speaks to their true condition. Although some dubious etymologies claim otherwise, the name was applied most likely as a metaphor for their existence. In the words of a former director of the Paris Opera: “The rats make holes in the scenery so they can watch the performance, gallop around behind the backcloth and play blindman’s buff in the hallways. They are supposed to earn twenty sous per show, but because of the huge fines imposed on them for their transgressions, they receive only eight or ten francs per month and thirty kicks in the backside from their mothers.”15 To other observers, the rat was mainly the transmitter of the “sexual plague,” syphilis. We are a long way from the charming and austere image projected by the Paris Opera’s current crop of students. Only in the twentieth century, as the starlets of the music hall and moving pictures attracted the glare of scandal and the heat of lustful desire, did classical dancers begin to gain a measure of respectability.

Why Edgar Degas, a solid bourgeois well known for his moral severity and a man, by his own account, obsessed with order, should have become fascinated by the louche world of the dance at such an early stage in his career and stayed with it for so long — roughly from 1860 to 1890 — is unclear. Was he one of the paunchy, top-hatted swains so often caricatured by Forain and Daumier who hardly stayed for the performance but took up a stand in the foyer after the first break, drinking champagne and cognac while waiting for the ballerinas? No, although as a young man—before he became an outright misanthrope — Degas had had his share of libertine adventures. Or so he liked to claim. But the aims of the lustful habitués were not his aims. He painted them, the predatory regulars, showed them lying in wait in a corner of the canvas or gathered in a group, strutting roosters in the henhouse. Sometimes he adopted their perspective, focusing in close-up on the bodies of the ballerinas. He observed these men for years. It was his world, his time, the reflection of his own desire as well, and “one can only make art from what one knows.”16 Also, Degas had a passion for music — Mozart, Gluck, Massenet, Gounod — which supplied his original and main rationale for attending the opera. His discovery that, in subtly choreographed ballets, dance “turns music into drawing” would come later.17 Then too, Degas was a creature of the night. Unlike the other Impressionists, and probably in part because of his eye problems, he did not seek out daylight scenes or sun-dappled luncheon parties. He preferred nighttime settings, the artificial light of theaters and cabarets, shadowy places.

That Degas should have been fascinated by dancers, independently of his male desires or his work as an artist, is not surprising. In the second half of the nineteenth century, the lives of dancers fascinated everyone, especially in Paris. Dancers belonged to the urban folklore that is so often braided into the history of great capitals. To understand the infatuation, one need only look at our contemporaries’ insatiable curiosity toward celebrities, which is characterized by a similar ambivalence. Objects of admiration and opprobrium, attraction and repellence, the “young ladies of the Opera” excited interest mostly for their sexual indiscretions and their romantic entanglements. Their tutus alone were a source of scandal and comment. Though longer than today’s tutus, they exposed a woman’s ankles and calves as no other garment of the period did. Two American ladies were reportedly so shocked that they walked out of a performance minutes after it started, seeing nothing in these short-skirted creatures but an attack on sober morals. Yet tales of the great heights to which dancers rose and the tawdry depths to which they sank inspired the work of artists, writers, and tabloid journalists. These stories were avidly followed in the popular quarters and the more cosseted precincts alike. Toward 1875, the renowned librettist Ludovic Halévy published a serial novel in La Vie parisienne about the adventures of the Cardinal family — an early avatar of the Kardashians — recounting the romantic adventures of Pauline and Virginie, two lovely ballerinas chaperoned by their mother, a cynical procuress, who was eager to sell her fourteen-year-old daughters to aging lechers; one of the girls eventually left the Opera to become a high-class cocotte. The novel was a huge success. Degas created an accompanying series of monotypes illustrating the life of the Cardinal sisters, but they were never published, as Halévy finally opted for a more conventional suite of images. Degas depicted the young girls in conversation with their admirers and shimmering before a mirror in the Opera’s foyer. He never showed them partnered by a male dancer, as though only feminine grace mattered — and men were only a foil. Other novels came out in the vein of Halévy’s, usually comical in tone. One such was the adventures of Madame Manchaballe and her three little rats (who lived on the rue de Douai, as the Van Goethems did), written by Viscount Richard de Saint-Geniès, a regular at the Paris Opera, hiding behind the jocular pseudonym of Richard O’Monroy. The penny press churned out potboilers with suggestive titles: Behind the Curtain, and The Young Ladies of the Opera. The sexualized, eroticized little rat inflamed the public imagination, appealing to men, of course, but also to women. Dance has always been the stuff of dreams, it is the romantic art par excellence, it personifies beauty, seduction, and perfection. People were riveted by the fact that it was possible to “pay 100,000 francs to a pair of ankles,” to a prima ballerina “whose name on the poster draws all of Paris, who earns 60,000 francs per year, and who lives like a princess,” as Balzac wrote, adding for the benefit of his visitor from the provinces: “If you sold your factory, the proceeds wouldn’t buy you the right to wish her ‘Good morning’ thirty times.”18

These stories fascinated the bourgeois public and frightened it at the same time. Tales of beautiful ballerinas turning the heads of eminent men and ruining their health, reputation, and career were a staple of the scandal sheets. The heroine of Zola’s Nana, an exact contemporary of Degas’s Little Dancer — who was in fact nicknamed “Little Nana” — had no talent as an actress. She merely stood onstage scantily clad and struck suggestive poses, but her performance so maddened men that it destroyed their lives — and then her own. She ended up disfigured by smallpox just as France was being defeated in the Franco-Prussian War of 1870, as though she stood for all that threatened the French nation, which was hopelessly in thrall to sensuality and debauch. Among respectable families of that era, a woman who worked was already suspected of depravity: an honest woman stayed home. So what could you possibly say about an actress or a dancer? Did she not express “the imperious offer of sex, the mimed call of the need for prostitution”?19

Ballet dancers, as the dubious cynosure of this shady world, were synonymous with corruption and degeneracy, linked with prostitutes who might bring crashing down a venerable genealogical tree. The dancer’s power was worrying: “The corps de ballet is the great power,” wrote Balzac. He cited the case of “a dancer who exists thanks entirely to the great influence of a newspaper. If her contract had not been renewed, the ministry would have found itself saddled with another enemy.”20 The “walkers” often ended up in houses of ill repute — the brothel was another common motif in painting and literature — but stars of the ballet and even third-tier ballerinas lived in “the high spheres of dandyism and politics.”21 Backstage and in the foyer of the Paris Opera, aristocrats, members of the Jockey Club, influential journalists, and politicians vied for the dancer’s attention. She might be mistress to a senator, or a peer of France, or a wealthy heir whose capital she was whittling away. Baron Haussmann, for instance, who masterminded the renovation of Paris, caused vast quantities ink to be spilled over his scandalous affair with a young ballerina. In that venal and hedonistic age, it was considered good form to “keep one’s dancer.” The sons of good families met ruin, committed suicide, or were ravaged by syphilis — all because of a dancer. In the “conspiratorial shadows” of the theater, evoked by Julien Gracq in his writings about Nana, the dancer had the terrifying power to destroy a noble line.22 Offering a point of contact between the lower depths and the elites of society, she braved “venereal fear,”23 she “sowed destruction, corrupting and disorganizing Paris between her snowy thighs,” she was “the fly that has escaped the slums, bringing with it the ferment of social rot,”24 and she was therefore a source of horror and fear, more even than of admiration and lust.

Did Degas fall prey to these alternately enchanting and horrifying fantasies that held the collective imagination in thrall? It seems not. The absorbing world of ballet may have played in his mind the role that myth played in the minds of earlier painters, but we cannot reproach him for sublimating his subject or prettifying the everyday reality of ballerinas. Where Ludovic Halévy presents us with a flurry of charming imps, laughing as they fluff out their gauzy skirts, Degas rarely shows us dancers under a glamorous light. He sometimes painted performances, but his more usual perspective was from backstage. In his canvases, we see the wearying work of rehearsals, the dancer’s body bent and weighted down with effort, the face tense or blurred or cropped out entirely, leaving more space for the legs and arms. This “iconoclast,” wrote Huysmans, was indifferent to the shopworn image of the ravishing ballerina endowed with the flesh of a goddess, instead revealing “the mercenary, dulled by mechanical movements and monotonous leaps,”25 whose body was simply the tool she used in her work, and who ended up collapsed after a strenuous session, her muscles sore and her neck in pain. The Dancing Lesson, for example, painted in 1879, shows the ballerina Nelly Franklin sitting in exhaustion on a bench, and Degas’s annotation reads “Unhappy Nelly.” A little rat might often be unhappy, especially if she lacked aptitude for her vocation. In his sonnets, Degas made fun of the talentless student who flubbed a dance movement: “Jumping froglike into the ponds of Cythera.”26 And the poet Henri de Régnier, in a verse portrait of Degas, praised the painter’s disillusioning art: “You’ve painted gauze flounces in delicate washes, / The satin slipper as it lands on the stage, / And the body’s full weight on the heel that it squashes.”27 By choosing Marie van Goethem as his model, a little girl with a flat chest and pinched features, Degas drove home his point all the more. This dancer is neither seductive nor a seductress, she is wearing not a beautiful stage costume but a simple and unornamented bodice; her nose in the air, she does not look at those who look at her, she exudes no sensuality that might excite the male observer. Her position is not one of the classic positions of the ballerina, she displays no lightness, no virtuosic ease, no particular grace. She is not depicted in rehearsal or in performance but during an ill-defined break, in a practice room, making no effort to please. Paul Valéry accurately summed up Degas’s paradoxical method, noting that he tried to “reconstruct the body of the female animal as the specialized slave of dance.”28 “For all his devotion to dancers,” wrote Valéry, “he captures rather than cajoles them. He defines them.”29

What Degas shows us, in fact, is not the mythical dancer but the humdrum worker; not the idol under the floodlights but the toiler in the shadows, once the oil lamps have been snuffed out; not the object of distraction and delight but the subject grappling with a sinister reality. As his friend the painter and author Jacques-Émile Blanche wrote, under Degas’s gaze, the dancers “stop being nymphs or butterflies…to fall back into their misery and betray their true condition.”30 Where Jean-Baptiste Carpeaux, ten years earlier, sculpted the beautiful Eugénie Fiocre, a prima ballerina at the Opera, as a countess or a duchess, with a rose in the elegant folds of her décolletage, and Degas painted the same Mademoiselle Fiocre as a fascinating Persian princess surrounded by her intimates, here he is offering up an entirely different vision. Marie van Goethem is only a young worker in the world of ballet, a little girl who is alone and solitary. No one is concerned about her fate. Degas depicts her in all her simplicity and destitution. The sculpture allows the emptiness around her to be suggested: no scenery, no company. You walk around a sculpture, taking it in from all sides the way you might examine a question from every angle. The “little Nana” stands against a backdrop of nothingness. Degas wanted to undermine the stereotype, assert a truth that society ignores — wants to ignore. Dance is not a fairy tale, it’s a painful profession. The little rats are Cinderellas without fairy godmothers, they don’t become princesses, and their carriageless coachmen remain mice, as gray as the cotton ticking of their slippers. They are children who work, the likes of dressmaker’s apprentices, child-minders, and salesgirls, but they work harder than the others. In his way, Degas was amplifying and anticipating the denunciations that the writers of his day would level at the industrial nineteenth century, when poor children were treated like slaves or animals. In 1862, Victor Hugo published Les Misérables, a novel that decries the tragic fate of children through the stories of Gavroche and Cosette. The despicable Thénardiers, who brutalize Cosette, owe their name to a political adversary of Hugo’s, Senator Thénard, who had opposed a bill to reduce the workday for children from sixteen hours to ten. Zola would defend this cause in his novel Germinal, and in 1878, Jules Vallès dedicated his autobiographical novel L’Enfant “to all those who, during their childhood, were tyrannized by their masters or beaten by their parents.”

But did Degas have such an overtly political end in mind when making the Little Dancer? Did he really want, as Huysmans would claim, “to throw in the face of his century” the outrages committed on the weak? There is one detail that might lead us to doubt it, hinting that the sculptor agreed at least in part with some of the prejudices of his time. Many of the detractors of this sculpture, on seeing Marie in her glass cage, thought she embodied “the rat of the Paris Opera…with her full store of evil instincts and depraved tendencies,”31 that she looked “thoroughly like a pervert”32 from the slums and had the features of a “criminal.” This last word, used by several critics, might surprise and shock today’s viewers. How could this young dancer in a tutu have anything criminal about her? And what is meant, in a concrete sense, by “features of a criminal”? How does one detect them? Do criminals share a facial type, different from a proper person’s? Can a propensity for evil, can moral degeneracy be discerned in a person’s visage — not, as in The Portrait of Dorian Gray, imprinted on it over time by the performance of criminal acts (itself an arguable concept), but in childhood, at the age of fourteen, as if one’s fate could be tattooed at the outset on one’s face? Can vice be “stockpiled” within the body, visible to the naked eye? We might as well be designated criminals at birth! Badness by nature! The idea is ridiculous.

There was nothing absurd about it to thinkers of the nineteenth century. In fact, it was the prevailing belief. In the late 1790s, Johann Kaspar Lavater’s The Art of Knowing Men by Their Physiognomy was widely read in France and elsewhere. A German theologian, Lavater — whom some consider the father of anthropology — envisioned a link between physical appearance and a man’s moral and intellectual capacity. For example, a man with a large jaw and a full-lipped mouth could be recognized as animalistic, whereas a broad, high forehead designated superior intelligence. Scientists also had a deep interest in phrenology, a theory that purported to explain man by his physical and organic constitution. An Italian specialist in criminal ethnography, Cesare Lombroso, following in the path of the German neurologist Franz Joseph Gall, held that the degree of development of a man’s faculties could be determined by the shape of his cranium, specifically its bumps and hollows. Character therefore is entirely determined by physical conformation. In French, we still say that someone has “the math bump” or “the business bump,” the only remnant today of this spurious hypothesis, but during most of the nineteenth century the idea was taken very seriously. Scientists were particularly keen on its use in the context of criminology. F. J. Gall, for instance, believed he had found “the crime bump” hidden behind the ears of murderers. Scientists collected criminals’ skulls, studied the organs of executed inmates, calculated “facial angle” as an index of the danger the subject posed, and measured the degree of masculinity in the faces of prostitutes — the deviance with respect to a gentle and passive femininity would explain their degeneration. The concept of the “born criminal,” advanced by Lombroso, linked an inclination to murder with simian features and a sloping forehead. Other criteria in the inventory, including left-handedness, baldness, prominent cheekbones in women, and the size and shape of the ear, also offered disquieting revelations. Delinquents were considered savages, primitives. A typology of criminals was devised that considered a working-class man to be “depraved from the cradle,” a barbarian under restraint, and the slums were thought to be a breeding ground for jailhouse stock. The features of the ancient Greeks, on the other hand, represented the aristocratic ideal.

These very materialistic theories, which fed into the ideas of Édouard Drumont and his French Anti-Semitic League as well as the racial classifications of the Nazis, were largely unopposed by any countervailing arguments. Only in the late nineteenth century did the thesis emerge that criminality does not originate in a physiological predisposition or an inherited trait. A few scientists, Georges Cuvier’s disciple Jean Pierre Flourens among them, did take an earlier stand against determinism, citing the role of human freedom and the power of reason. Others, foreshadowing modern sociology, insisted on the influence of environment and education in countering the tyranny of biology. Their efforts were largely unavailing, and the determinist argument prospered among intellectuals and held sway in the public sphere. France was industrializing, and its working class was growing in importance. Paris, under the influence of Baron Haussmann, was seeing its heterogeneous population shuffled together in individual buildings — the rich on the lower floors and the servant class under the eaves. The ruling classes needed to be reassured about their privileges. Small wonder that they clung to theories that “proved” the natural superiority of the bourgeoisie over the working class, the rich over the poor, whites over blacks, and men over women. Man, according to this view, which is rife with racial and gender chauvinism, is not influenced so much by his social and cultural environment as he is determined by heredity and the laws of biology. Therefore workingmen, prostitutes, blacks, and women were naturally inferior by reason of genetic flaws or an incomplete development. Social hierarchy was justified by nature itself, with rich white men at the apex and other races, women, and the poor in the lower depths. Which is to say that Marie van Goethem, with her “Aztec” features and her young girl’s poverty, belonged at the bottom of the order. To a large extent, this explains the horror that the public expressed on first seeing the Little Dancer when it was exhibited in 1881. The bourgeois viewer looked at the work and saw his own antithesis. His preference was for Madonnas, for refined and elegant models, or for plump, healthy young women. He could not fathom why a common, hardworking Opera rat with the face of a “monkey” and a “depraved” aspect should be the subject of a work of art. Why would you represent someone from the dregs of society, what would be the point?

The face of the Little Dancer undeniably has some of the features identified by the phrenologists and medical anatomists of the day as typically criminal: a sloping forehead, a protruding jaw, prominent cheekbones, thick hair. It has been reported that Edgar Degas sought out information on these physiognomic theories, which are illustrated in several of his oil portraits and monotypes of bordellos. He was not alone. Research into physiognomy was highly admired by the writers and artists of the nineteenth century. Honoré de Balzac, for instance, owned the complete works of Lavater, illustrated with six hundred engravings, from which he chose the features for his characters according to the temperament he planned to assign them: ugly face, evil soul. Émile Zola confessed to having read all of Lombroso, who helped him understand the influence of bloodlines and the hereditary nature of degeneracy. Victor Hugo visited prisoners to see whether their criminal tendencies were etched in their faces. The artist David d’Angers, a follower of F. J. Gall, carved portrait medallions illustrating his theory of bumps. When Degas, to the horror of his audience, rendered this vision of the criminal face in full, it was immediately decried as “an ethnographic aberration” and “a monster.” He acted entirely within the tenor of his times and in full awareness of the disapproval he was courting. But what was his intention in sculpting the face of his Little Dancer as he did?

It is always hard when an artist we admire reveals serious moral or intellectual failings, even if part of the blame lies with the “times” — “it was normal for those times” — or with a defect of character. Degas’s anti-Semitism has been amply attested. He was not rabid in his beliefs, but his anti-Dreyfusard stance was vehement enough to cause a rift with his old friends the Halévys in 1897, following a heated discussion about the Dreyfus affair. Even if we believe that his animus toward Captain Dreyfus, a Jew, owed more to his great devotion to the army than to a visceral anti-Semitism, it hardly makes him likable. Similarly, we need to review Degas’s ambiguous attitude toward the opposite sex, which shows little influence of feminism. A parallel question is whether Degas believed in the fashionable physiognomic theories of his time, to the point of wanting to illustrate them by modeling his Little Dancer‘s features to resemble those of a delinquent. Did he choose her, this little working-class rat, to make her the antithesis of the young lady of good family, living proof of the eugenicist arguments of the time? Or, on the contrary, was the sculpture intended to create a needed scandal, exposing the racist roots of this pseudo-science and the abjection of society?

Several indications argue in favor of the first hypothesis. At the 1881 exhibition where he showed the Little Dancer, Degas also presented a study called Four Criminal Physiognomies. Huysmans described the subjects thus: “Animal snouts, with low foreheads, prominent jaws, recessive chins, lashless and evasive eyes.”33 The sketches show the heads of four young men indicted for murder, drawn by Degas from life while attending their trial in August 1880, at a time when he was still working on his Little Dancer. All of Paris shared a lively interest in the “Abadie affair,” so called for the lead defendant in the case, arrested at the age of nineteen with one of his friends, Pierre Gille, sixteen, for the murder of a woman cabaret manager. A second trial followed a few months later, centered on Michel Knobloch, also nineteen and indicted five times already, who belonged to the Abadie band and had confessed to murdering a grocer’s clerk. All three were sentenced to death. The horrible nature of the crimes and the youth of the suspects, all of them from the lower depths of society, shocked the French public and revived the topical question of juvenile delinquency. One aspect also rekindled a literary quarrel. Before their arrest, Abadie and Gille had been recruited for walk-on parts in a theatrical adaptation of Zola’s L’Assommoir. The stage manager at the Ambigu Theater had gone scouting in some of the dicier quarters of Paris and hired these youths as perfect physical specimens of the degenerate milieu Zola described. In the wake of it, naturalist writers were reproached for showcasing the ugliness of the world. They were further reviled for “depoeticizing man”34 and taking pleasure in “tawdriness,” apparently to terrify the bourgeois reader by “habituating him to the horrible”35 and depriving him of his right to the beautiful.

But this was just what interested Degas, who confided to his Notebooks his ambition to make “a study of the modern sensibility.” He was able to attend the trial regularly, thanks to one of his friends who was serving as an alternate juror. While following the trial, he drew the defendants in his sketchbook, later making several pastels.

Contemporary art historians have sought to compare Degas’s portraits to the originals. During a symposium on Degas at the Musée d’Orsay in 1988, one of the great specialists on the nineteenth century, Douglas Druick, brought together Degas’s drawings and the anthropometric photographs of the accused that were made by the Department of National Security at the time of the gang’s arrest in 1880 and preserved at police headquarters. The comparison shows very clearly that Degas accentuated certain facial features to bring them in line with the trending ideas of criminal ethnography. He gave the young men lower foreheads, more recessive chins, and a more animalistic aspect than they had in reality. It therefore seems that Degas wanted his drawings to reflect theories of social delinquency that he subscribed to. Remembering that he chose to exhibit his Criminal Physiognomies together with his Little Dancer, linking them by their obvious resemblance — their faces seem to attest to a hateful blood relationship — we can reasonably surmise that Degas did for his dancer what he’d done for the youths in court and altered his young model’s natural features to resemble those of a criminal. Of course, she never murdered anyone, but according to Dr. Lombroso her offense was no less serious: “Prostitution is the form that crime takes in women.”36 For their power to deprave, “girls” of a certain kind were subject to the same contempt and the same efforts at suppression as murderers. And this, in fact, is how Marie was perceived by all the reviewers — as a prostitute, either actual or prospective, a painted woman. The critic Paul Mantz voiced this general feeling, attributing to Marie “a face marked with the hateful promise of every vice.”37 And viewers compared her to a “monkey” or an “Aztec,” relegating her, as Douglas Druick noted, “to the earliest stages of human evolution.”38 She was thought to look “dull” and “without any moral expression.” She was likened to an animal, fit only to be “trained” for the stage. She was seen as a specimen suitable for the Musée Dupuytren, where wax replicas of human bodies with various illnesses were exhibited (was she not herself made of wax?) and various pathologies were displayed in glass jars (was she not herself in a “cage” made of glass?). Or she belonged in the newly opened Ethnographic Museum on the place Trocadéro.

At this juncture, we may be startled to realize that Marie van Goethem probably did not look like Degas’s sculpture, that what we see is not her true face, for he also gave those features to others, to men older than she, to women in a shadowy brothel, and to a well-known cabaret singer. He probably flattened the top of her skull and altered her facial angle to make her jutting chin a kind of “plebeian muzzle,” as he wrote in one of his poems. When we look at the preparatory drawings for this sculpture, we see how he changed her face to give it the hallmarks of a savage, quasi-Neanderthal primitivism, a precocious degeneracy. He literally altered her nature. The contrast with the delicate portraits Degas made of his own sister Marguerite, who had fine features, a genteel oval face, and neatly combed hair, is extreme. It is hard not to loathe this forty-something conformist who, in modeling his wax, manipulated a very young girl for reasons that have nothing to do with art or esthetics. Art need not be an exact imitation of life, but must we accept that a young creature be sacrificed to the suspect ideology of the artist?

Yet Degas never set the artist above the rest of mankind, nor did he consider himself a privileged being. Such superciliousness would hardly correspond to what we know of him. More pertinently, it’s hard to believe that Edgar Degas limited his ambition to being an ethnographer of the working-class environment. True, the critic Charles Ephrussi praised the sculpture as “scientifically exact,” but was the artist’s intention to pursue science? Was his aim to provide a clinical description documenting a kind of “criminal aspect” at an early stage? This is hard to believe, especially from Degas, who was so passionate about his art.

On the other hand, the artist may have had a moral goal in mind. Those who knew him well often described him as a moralist. “Art,” said Degas, “is not what you see, but what you make others see.” By sculpting this little dancer into a criminal, was he not holding up a mirror to the viewers who protested at the sight of her? Those who decoded the signals given by this sculpture — evil, vice, ruination — had the chance to interpret them in light of their own lives and the society around them. Might not a different fate befall this sickly child were there no men to lead her astray and no women to despise her? While Degas may have accentuated her animalistic side, he did no less when painting the clientele of brothels — big-bellied men with sloping foreheads and porcine snouts — again with the intention of denouncing social hypocrisy. Was it not a subscriber to the Paris Opera, in a novel by Richard O’Monroy, who explained cynically: “I have a passion for the beginners, the little rats still living in poverty. I enjoy being the Maecenas who discovers budding talent, who sees beyond the bony clavicles and work-reddened hands to forecast a future flowering”?39 It was these respectable men who, in their way, fashioned the Marie van Goethems of the world and created little “criminals” — victims, actually. And the discomfort that many visitors to the 1881 exhibition felt came from the fact of being subscribers to the Paris Opera themselves, who suddenly found the object of their private desires exposed to public view and made uglier by their own perversion. Furthermore, Degas engaged Marie van Goethem to pose for other sculptures and paintings whose meaning was altogether different. Her face, for instance, is perfectly recognizable in a statuette called The Schoolgirl, made in 1880, around the same time as the Little Dancer. A well-dressed young lady, not bareheaded this time but wearing a hat, and not in a tutu but a long skirt, carries a stack of books. Nothing shocking, nothing “venal.” Here is what Marie might have become if economic necessity and social inequality had not kept her from it, although stamped with the same supposedly criminal features: a charming schoolgirl. Over the course of his career, Degas had a number of models from eighteen to twenty years old. In choosing Marie van Goethem and in spelling out her age, Degas was underlining what should have been obvious to all: that she was a child. A little girl who had barely reached puberty, she was already a lost soul in everyone’s eyes. If he chose to reveal her ugliness, knowing that the public of his day equated physical and moral ugliness, it was because he aimed to be unsettling. He wanted to show reality, not flatter the tastes of the bourgeois. And he succeeded beyond his expectations: in representing a young girl of this type, he disturbed the French in part because, recently defeated in the Franco-Prussian War, they were ready to attribute the Prussians’ victory to their superior moral and intellectual education — so one might read in the daily papers, and so one might hear at café counters. The nineteenth-century bourgeois were terrified—but are not the bourgeois in every age? — at the prospect of a new generation rising after them that was devoid of principles and therefore capable of destroying them. Degas only awakened this anxiety.

In his writings on Degas, Jacques-Émile Blanche compares him to his contemporaries. He contrasts him, for instance, with Gustave Moreau, famous for his Salomes, who sought refuge in myths, symbols, and abstraction because his “small stock of humanity” kept him apart “from life and ugliness,” whereas Degas took on the most seemingly vulgar subjects and extracted a beauty from them “not previously seen by painters.” Moreau and Degas, Blanche adds, were both “Savonarolas of esthetics,” zealous workers in service to perfection of form. But esthetics did not lead to the same endpoint for both. Gustave Moreau worked to captivate and seduce. By contrast, Blanche wrote, “Degas did not seduce, he frightened.”40 And because Degas was well-born, his provocations carried all the more weight. To unsettle so as to stimulate thought, to make art that was critical and served truth, though truth might be cruel, such were the aims of Edgar Degas, in his extreme modernity. He said as much in his Notebooks, writing about Rembrandt’s Venus and Cupid: “He has introduced that element of surprise which provokes us to think and awakens our minds to the tragedy inherent in all works where the truth about life is bluntly expressed.”41 Surely the same applies to the Little Dancer Aged Fourteen. Degas intended this sculpture to give a sense of surprise, a salutary shock, opening the viewer’s mind by presenting not an elegant work that would flatter his esthetic sense but a societal tragedy, to which he was contributing. The earliest critics of the work did, in fact, react with terror. Here is Louis Énault: “She is absolutely terrifying. Never has the tragedy of adolescence been represented with more sadness.” For Degas, “the truth about life” was not to be found, as Michel Leiris would say about a certain kind of estheticizing literature, in the “vain graces of the ballerina,” but in the tragic and already determined — tragic because already determined — destiny of this very young girl. Truth was the foundation block of modernity. Cézanne must have had this in mind when, in 1905, he made his famous promise to Émile Bernard: “I owe you the truth in painting, and I will tell it to you.”42

As to the “element of surprise” that he admired in Rembrandt, Degas achieves it in this sculpture not from the commonness of the subject or the reference to social misfortune alone. The manufacture of the work was in itself a great source of surprise and astonishment. In the first place, the Parisian public of the nineteenth century was not used to seeing wax sculptures — where were the marbles of Rodin, the bronzes of Carpeaux? True, specialists would have known the figurines of Antoine Benoist, notably his portrait of Louis XIV in Versailles, but these “wax puppets,” as La Bruyère called them, had been out of fashion since the end of the seventeenth century. A few polychromed statues had attracted the interest of collectors, but they were little known to the general public. And aside from two or three Madonnas, also dressed and wearing makeup, in a few scattered churches, the visitor would never have seen a statue wearing real clothes and a horsehair wig — or could it possibly be a wig made of real human hair? More accurately, the visitor would have known such objects, but not in the context of an exhibition hall dedicated to art, not shown as a work of sculpture. He would have seen wax figures of humans at the milliner’s, in the dress shop, and in the windows of the early department stores. He would have seen them at the Musée Dupuytren, in the Cordeliers Convent, which displayed reproductions of human bodies affected by a variety of pathologies, malformed fetuses, likenesses of murderers, and anatomical wax models displaying terrifying venereal diseases. He would have seen them at fun fairs, as entertainment, and at universal expositions, in the context of colonial ethnography — this is how he would have learned what the indigenous peoples of far-off countries looked like. He would have seen them at Madame Tussaud’s in London, the first museum to showcase life-sized wax sculptures that perfectly replicated the features, aspect, and clothing of famous figures. He would have seen them from 1865 to 1867 at the Musée Hartkoff, on the passage de l’Opéra, and at the Musée Français on the boulevard des Capucines, where the model-maker Jules Talrich exhibited statues of literary and mythological characters. And, the following year, he would see them at the Musée Grévin, which was patterned after Madame Tussaud’s. As in London, the museum revived the ancient tradition of wax death masks, but using contemporary models, life-sized, in their full glory and their best finery. The Musée Grévin even featured one of the famous dancers at the Paris Opera, the Spanish star Rosita Mauri, wearing one of her ballet costumes. Her likeness was among those chosen for the museum’s inaugural show in June 1882.

But in the Salon des Indépendants, the viewer felt almost offended. He hadn’t gone to the fair or to the toy store, hadn’t gone to the milliner’s. He wasn’t attending a universal exposition, in search of exoticism; nor had he come to be frightened by anatomical monstrosities. No, he was there to discover works of contemporary art. And what did he see in a glass case, presented on a satin cloth as though it were an ethnographic curiosity or artifact? A doll, a common wax doll! Somewhat larger than an ordinary doll, maybe — the sculpture measured just over three feet in height, the size of an average three-year-old —not as pale in color as a doll, nor as closely imitating human skin, but entirely unworthy of a sculptor. Would Rodin ever have thought to gussy up his statues in this way? Insanity. In his review, Huysmans harked back to the polychrome sculptures of Spain, assigning a sacred dimension to the Little Dancer by comparing it to the Christ in the Burgos Cathedral, “whose hair is actual hair, whose thorns are actual thorns, whose drapery is actual fabric,”43 but the link was tenuous. And Degas’s dancer was in no way as attractive as the Tanagra figurines that had been on view at the Louvre for the past dozen years. Certain art historians noted that the lost-wax technique Degas used had been invented by the bronze casters of ancient Egypt, who also colored their sculptures, thus linking the Little Dancer to the Seated Scribe, one of the Louvre’s masterpieces. But for the public as a whole, the sculpture stood outside the artistic tradition as an object of popular culture, like the dolls that had been mass-produced since the middle of the century. And when you thought about it, there were many dolls more beautiful than this one, hand-painted, with silky hair and eyes of colored glass. Some were even automated. Among the displays of new technology at the Universal Exposition of 1878 were a variety of dolls: a Gypsy that danced, a little girl who walked, and a crying baby. The French of that period had a passion for dolls, and they figure in many paintings by Renoir, Gauguin, Pissarro, and Cézanne. Little rich girls had a good laugh or a good cry (as I did a hundred years later) reading the Countess of Ségur’s The Misfortunes of Sophie, in which the little heroine treats her wax doll to a hot bath and watches in horror as the doll melts away! The doll that Jean Valjean gives to Cosette in Les Misérables has left a deep mark on the book’s more self-possessed readers and brought everyone else to tears: “Against a backdrop of white napkins, the shopkeeper had placed an enormous doll, almost two feet tall, wearing a pink crêpe dress and a golden crown of wheatears, with real hair and enamel eyes. All that day, this marvel had been displayed to the wonderment of passersby under the age of ten, and yet there was not in Montfermeil a mother sufficiently rich or sufficiently extravagant to offer it to her child.”44 Cosette’s love of dolls was shared by the Parisian public. The manufacturer Montanari made a fortune turning out wax dolls and figurines; the Schmitt and Jumeau companies competed to create the most ingenious mechanisms, the most realistic costumes — Indian, Mexican — thereby flattering the public’s taste for ethnographic curiosities and exoticism. According to Degas’s first biographer, Paul Lafond, the artist kept a collection of Neapolitan dolls in traditional costume in his dining room. He attended the puppet theater in the Tuileries Gardens regularly. He did not hide that he had thoroughly studied the fabrication of dolls, as well as the mechanisms of automatons and the research on locomotion by Étienne-Jules Marey. He also revealed that he had consulted Madame Cusset, a famous wigmaker, to make his dancer a beribboned ponytail. But once again, the public questioned what this had to do with the fine arts. The art critic George Moore, who was a great admirer of Degas’s wax sculptures, would later offer this comment: “Strange dolls — dolls if you will, but dolls modeled by a man of genius.”45 Meanwhile, the controversy raged.

And then, finally, this clothed sculpture struck visitors to the exhibition as obscene. While they went into ecstasies over the Venus of Milo and many other statues of women with exposed bodies, Rodin’s dancers among them—here was another sculptor fascinated by the movement of dancers — they found the clothing that covered the Little Dancer shocking. Because if she was wearing clothes, it meant that she was naked underneath! The model posed naked, as was the custom in many ateliers and art schools, and normally this was either ignored or accepted on the grounds of the higher interests of art. The nudity of classical statuary shocked no one. In painting, of course, there had been recent and memorable scandals, starting in 1863 with Manet’s Olympia and his Déjeuner sur l’herbe, in which the naked woman in the foreground looks at us mockingly. And there was Courbet. Contemporary naked women who were not Eves, not goddesses, not allegories of Truth, but women of today, ones you might meet in the street, that is what was intolerable to the public. The garments ornamenting the Little Dancer, paradoxically, pointed to her essential anatomy. The clothed nude is more obscene than the naked; the visible suggests the hidden. Her nudity might be veiled, but one was led to think about it, to visualize the conditions under which art was made, to reflect on the mores of bohemia and the wantonness of models, provoking feelings of shame and hatred.

With this sculpture, then, Degas transgressed twice over, breaking the rules of polite society and those of academic art. His taboo-breaking revolution was both moral and esthetic. On the one hand, he chose a scabrous subject that ran afoul of moral standards; on the other, he undermined the very foundations of statuary art. While Huysmans praised Degas as an artist who rejected “the study of classical art and the use of marble, stone, and bronze,” thereby rescuing his work from a stultifying academicism, the guardians of the temple reviled Degas for “threatening the very identity of sculpture.”46 “It’s barely a maquette,” they said, and more like a piece of merchandise, something you could pick up in a bazaar. Degas was in fact well known for calling his works “wares” and “products.” His open avoidance of elitism profoundly shocked the partisans of high art. The very conservative critic Anatole de Montaiglon, scandalized by the shop windows of the dressmaker Madame Demarest, which were much talked about during the Universal Exposition of 1878, wrote with prescient irony: “These clothed mannequins in apparel shops are destined to become the latest fashion in art.”47 In the end, what was most disturbing was the inability to assign the Little Dancer to any fixed category. She was everything and its opposite: the model was a child, but she looked like a criminal; a ballet dancer, but inelegant — at once “refined and barbarous,”48 wrote Huysmans, “an admixture of grace and working-class vileness.”49 Too large to be a toy, too small for a girl of fourteen, the Little Dancer hovered between the work of art and the everyday object, the statue and the mannequin, the doll, the miniature, the figurine. She advanced a tightrope walker’s foot onto the wire stretched between the fine arts and popular culture, between poetry and prose; she was both classical and modern, realistic and subjective, esthetic and popular, common and beautiful. “This enigmatic little creature, who is at once sly and untainted,”50 suggested different interpretations while not being reducible to any, and refused to be boxed in by anything but her glass cage. The cage itself resisted any simple explanation: ordinarily, in museums, glass cases are reserved for objects — or taxidermied animals, hence the word “cage,” which was used by some (while others used the word “jar”) who found it appropriate for this “animal.” The fabric she stood on also excited speculation: the base of a statue normally has no such adornment, which is more commonly seen in commercial displays. (It works fine for Cosette’s doll, but for Degas’s statue?) The satiny fabric also suggested Courbet’s recent painting, The Origin of the World, in which a woman’s genitals are displayed against a similar white cloth. The painting had not been exhibited publicly, but a few insiders, Degas among them, were likely to have seen it. For those in the know, the obscene association would have seemed obvious and deliberate. On the other hand, Degas, though in the prime of life, already lived as a quasi-hermit, a recluse in his studio. His reputation was unblemished by any scandal, unlike Courbet’s, and no whisper of depravity attached to him. By putting a transparent obstacle between his statue and the public, by preventing his dancer from being touched, might not Degas have been displaying a haughty modesty, preserving the work’s value, its rarity, and even its sacred dimension? One hardly knows what to think.

Even those who defended the work and saw in it “the first formulation of a new art,” in Nina de Villard’s words,51 were unsettled as to its classification. The Little Dancer might well be called “the first Impressionist sculpture,” but did it not reflect instead an extreme form of realism?

Degas is lumped in with the Impressionists, but it is only because he took part in the secessionist movement of the early 1860s that defined a group in opposition to the reigning academicists. Unable to exhibit in the official salons, a number of artists, including Renoir, Monet, and Manet, took over a parallel exhibition hall known as the Salon des Refusés. But this salon, which only lasted a few years, was subject to violent attacks. Edgar Degas then joined with Claude Monet, Auguste Renoir, Paul Cézanne, Berthe Morisot, Alfred Sisley, and Camille Pissarro, all of them tired of the hostility of the official authorities, to form an association dedicated to mounting their own exhibitions. In December 1873, they adopted the generic name Société anonyme des artistes peintres, sculpteurs et graveurs, but were ironically rechristened the “Impressionists” by a critic who singled out Monet’s canvas Impression, Sunrise. The Impressionists: the name would stick, to the great displeasure of Edgar Degas, who had proposed the name “Intransigents” and considered himself part of a “realist movement.” This separation from the others explains much about Degas. The critics were well aware of it. “Proximity is not kinship,” they noted, and although Degas exhibited alongside Pissarro, Sisley, and Monet, “he was an alien in their midst.”52 His friend Jacques-Émile Blanche underlined the fact in his recollections: “Monsieur Degas was called an ‘Impressionist’ because he belonged to the group of painters Monet christened with that name; but Monsieur Degas was among them as an outsider. He painted emphatically, instead of ‘suggesting’ by rough signs, or equivalents, as those landscapists did who, not yet daring to call their sketches ‘paintings,’ classified them as ‘impressions.’“53

He painted emphatically, instead of suggesting. He didn’t seduce, he frightened. It’s worth bringing these two phrases of Jacques-Émile Blanche’s together. They express the essence of Degas’s work, at least during those years: he emphasized and he frightened. He emphasized in order to frighten. He “impressed” but in a different way than his painter friends. Huysmans, following Blanche’s lead, contrasted him to Gustave Moreau, whose work, he wrote, lay “outside any particular time, flying into the beyond, soaring in dreams, far from the excremental ideas secreted by a whole nation.” Degas, on the contrary, belonged to that family of painters “whose mind is far from nomadic, whose stay-at-home imagination cleaves to the actual period,” and whose work is entirely taken up with “this environment that they hate, this environment whose blemishes and shames they scrutinize and express.”54 It is the eternal battle in the arts between those who live in their imaginations and those who are fiercely committed to reality. Huysmans not only placed Degas in the latter group but named him one of its most personal masters, “the most piercing of them all,” who, by his “attentive cruelty,” gave “so precise a sensation of the strange, so accurate a rendition of the unseen, that one wonders at being surprised by it.”55 Degas, though he admired the work of Gustave Moreau, could be cuttingly sarcastic about the imaginary accessories in his paintings: “He wants us to believe that the gods wore watch chains.”56 But though he drew a line between himself and artists such as Moreau, who took their inspiration from mythology and the ideal, he was not to be confused with the Impressionist school then coming into its own. It was true that the Impressionists, like Degas, had broken away from historical, mythological, and religious subjects, from the pomp of their predecessors. Renoir, for example, described his relief at escaping the sculpture hall of the Luxembourg Museum and “those terrified and too-white statues,”57 diametric opposites of the Little Dancer. Degas also shared the Impressionists’ love of contemporary scenes and their taste for technical inventiveness and creative freedom. But unlike them, he hated to work outdoors and was passionately attached to drawing, and therefore to the outline. More significantly, he looked at the world with less forgiving eyes, and his vision was orders of magnitude less lighthearted. While Claude Monet and Camille Pissarro expressed their wonderment at nature and its vision-blurring tricks of light, while Mary Cassatt, Auguste Renoir, and Berthe Morisot presented charming scenes of middle-class and family life, with women and children shown in all their beauty, Edgar Degas captured an unfiltered reality and provoked disquieting sensations. He questioned society. In this sense, he was much more a realist than an Impressionist. His contemporaries, in fact, reproached him for pushing his realism to extremes. It was all well and good to tear down “the partition dividing the atelier from ordinary life,”58 but he went too far in applying “the major rule of naturalism,” which was to exaggerate physical and moral ugliness. Even his friends deplored his tendency always to “search within the real for the defective grain.”59 Just taking representations of childhood, we won’t find much in common between the Little Dancer Aged Fourteen and Berthe Morisot’s Eugène Manet and His Daughter in the Garden at Bougival, painted the same year, or Renoir’s Child with a Bird, both of which feature lovely little girls who are happy and protected. On this score, critics spoke of the Impressionists’ “social blindness,” which divided them from Degas. Despite his reputation as a haughty bourgeois, Degas has more in common here with such predecessors as Millet, who was attentive to rural poverty, and to contemporaries now somewhat fallen from favor, such as Fernand Pelez, a painter of street urchins.

It is therefore difficult to accept the Little Dancer‘s title to being “the first Impressionist statue,” given that the sculpture’s very technique, its three-dimensionality, and its accessories further accentuated its realism. It is also a work whose fragile material provided an analogue for the state of contemporary society, a society that came into being at a time when literature was dominated by an exceedingly harsh strain of naturalism. We should remember, however, that Émile Zola, though the leader of this school of writing, rejected what he called “photographic realism” in painting. In 1878, he criticized Gustave Caillebotte’s The Floor Scrapers for being “bourgeois by reason of its exactitude,”60 though he would soften toward the painter in subsequent years and praise him for his “courage” as a truth teller. What made the difference between a flat, dutiful verisimilitude and inspired realism was obviously talent — Degas’s palette, for instance, with its greens, blues, and pinks, was far removed from nature. Degas was certainly looking for reality, but “what he asked of reality was the new.”61 For him, as for Delacroix before him, “everything was a subject,” there were no marginal or vulgar motifs. Chafing at the label of “Impressionist,” Degas would have preferred to be identified as an “Intransigent.” And we can see why: he doesn’t compromise with the truth. Stripped of any effect that might embellish reality, his sculpture clashed with bourgeois taste, just as the novels of Zola and Maupassant did, disappointing the imagination and offering an art “pruned of all fancy,” which no doubt had its place, according to the critic Paul Mantz, “in the history of cruel arts.”62 Unlike most of the Impressionists, he didn’t emphasize the sort of classic beauty presented in ideal form by earlier masters. In the words of art critic Joseph Czapski, “Degas discovered another beauty in the reality around him…a totally new and tragic beauty.”63 Going further, Czapski attributes to Degas “the discovery of ugliness, which the painter changes into artistic beauty, the discovery of baseness and brutality, which, transposed, becomes a perfect work of art.”64 If Degas broke the harmony that pervaded the art of his admired predecessors, it was to express, Czapski continues, “the moral tragedy of the period…the material and spiritual upheavals of his time, and that was his greatness.” But, he concludes, “morally, philosophically, religiously, it represented a collapse of something, a tragedy.”65

MARIE VAN GOETHEM was an instance of this tragedy, its witness, its model, its fetish, its symbol. Degas’s masterpiece, in its modernity, may mark a break with the esthetic past, but the “collapse of something” also corresponds to someone’s lived reality: Marie was there, she is in the work. That’s why the story of the Little Dancer Aged Fourteen can’t end here. What is still missing, what I have not found — I who seek to know everything about her — is something that is neither moral nor philosophic nor religious, or rather something that is all those things together. Beyond the physical, and beyond the critical reviews, what is missing is her soul. Degas’s ghost instantly takes issue, the painter having always objected strenuously to talk of the soul and “the influence of the soul.” “We speak a less pretentious language,” he said, claiming to be subject only to “the influence of the eyes.”66 The word “soul” may be in disuse, permeated with religion — and the thing itself may be unlocatable — but it pertains to all works of art, beyond what the senses perceive. The sculpture cannot simply embody a period, a state of society, an esthetic, nor even a modernist or avant-garde movement. What makes it a universal work of art is precisely what evades all these meanings, however strong or essential they may be, what transcends them. And at the other end of the equation, it is what each person may find there for herself, outside of time, in attunement with her own personal narrative.

Huysmans described Degas’s brand of realism as “an art expressing an expansive or abridged upwelling of soul, within living bodies, in perfect accord with their surroundings.” Zola, for his part, wrote that the work of art is “a corner of creation viewed through a particular temperament.”67 Marie van Goethem was that corner of creation — a modest fragment, neither particularly visible nor particularly attractive — and Degas was that temperament — visual, tactile, and very solitary. What were they doing together? Why were they both there? What “upwelling of soul” or what spirit was born of this couple? By what mystery, by what detours, by what desires? What was happening in these living bodies, whose encounter would give birth to a work of art and give rise to an extended future existence for themselves?