Part Three

Leviticus

If you like ritual, this is the book for you.

Beginning with detailed breakdowns of altar offerings, ranging from rams and he-goats to oxen, this is a volume in which the blood, organs, and smoke of sacrifices always linger.

No need for narrative here! The text reads like a crash course in Israelite legislation, concerning matters of purity, priestly probity, genital infections, and bestiality. The prescribed dose of fire, water, oil, or blood appears able to correct most things. It also makes this book tough going for most first-time readers.

Michelle Quint

Va-yikra (“And he called”) Leviticus 1:1–5:26

Rachel Levin

Tzav (“Command”) Leviticus 6:1–8:36

David Sax

Sh’mini (“Eighth”) Leviticus 9:1–11:47

Jamie Glassman

Tazri·a (“She conceives”) Leviticus 12:1–13:59

Tim Samuels

M’tzora (“Being diseased”) Leviticus 14:1–15:33

Amichai Lau-Lavie

Aharei Mot (“After death”) Leviticus 16:1–18:30

A. J. Jacobs

K’doshim (“Holy ones”) Leviticus 19:1–20:27

Dana Adam

Shapiro Emor (“Speak”) Leviticus 21:1–24:23

Mireille Silcoff

B’har (“On the Mount”) Leviticus 25:1–26:2

Christopher Noxon

B’hukkotai (“By my decrees”) Leviticus 26:3–27:34

“He shall then present, as an offering by fire to the Lord, the fat from a sacrifice of well-being: the whole broad tail, which shall be removed close to the backbone; the fat that covers the entrails and all the fat that is about the entrails.” —Leviticus 3:9

VA-YIKRA (“And he called”)

Leviticus 1:1–5:26

The mystery of offerings is revealed. The Lord breaks down the specific categories of altar offerings so that Moses can explain the technical mechanics of sacrifice to the Israelites:

“Burnt offerings” require male bulls free of blemish. Aaron and his sons are to splash the blood against the altar before burning the flayed sections on a wood fire. A similar procedure is outlined for sheep or goats. If birds are brought for sacrificial purposes, only turtledoves or pigeons will suffice.

The recipe for “meal offerings” is spelled out: flour mixed with oil and frankincense. Unleavened cakes, wafers, grain, or fruit can also serve. The priests are to burn a token amount, but should feel free to eat the remainder.

“Sacrifices of well-being” are male or female livestock free of blemish.

“Sin offerings” for inadvertent transgressions require an unblemished bull, unless the sin is performed by a tribal chief, in which case a goat will be needed.

A “guilt offering,” necessary in the case of an unwitting transgression of a sacred commandment, can take the form of a female goat or sheep.

A person guilty of failing to testify when in a position to do so, of touching an unclean object like a carcass, or of breaking a forgotten oath can rectify the situation by offering a sheep or goat, two turtledoves or two pigeons—one for a sin offering and the other for a burnt offering—or, if the lawbreaker is impoverished, choice flour and oil.

If a person has been sacrilegious, a ram or its equivalent worth in silver shekels is required. A ram is also needed for someone guilty of deceitful dealings with other humans, be it through broken pledges, robbery, or fraud. A restitution payment of the principal amount plus 20 percent is also demanded.

Michelle Quint

THE TENT OF MEETING: AN OFFERINGS GUIDEBOOK FOR YOUR KITCHEN

Tony’s Bloody Guilt Roast

When we first put this dish on the altar, it brought a lot of guilty Israelites into the Tent. So we heard a lot of opinions. Some folks prefer to do the slaughter inside or flash fry smaller strips of fat. But at the Tent, we like to keep our floor clean and our cuts large.

Big cuts of meat—like you’re going to have with a bull—are some of our favorite offerings to burn at the Tent, because they’re so easy to do well. The Lord might disagree, but we think that, at the end of the day, it doesn’t really matter if you do entrails first or last, because that liver/kidney/loins combo is impossible to beat.

Throw a hunk on your altar and let it rest a good, long while. You might notice the meat shrinking and be tempted to jump in there. Don’t do it. Meat is a muscle, so it’s going to contract as it burns. If you’re doing it right, that bull is going to get nice and smoky. Just relax. You can’t rush a good guilt offering.

Ingredients

1 bull of the herd

7 bunches aromatic incense, such as bay leaf, frankincense, or hyssop

40 pounds hickory wood chips for the altar

Salt and pepper, to taste

Variation: If you can’t get a bull, you can sub in a sheep or an ox (just make sure it’s blemish-free).

Active Prep Time: 6 hours

Total Cook Time: Three days/three nights

Servings: One for the Eternal, blessed be He, or 40 appetizer portions

Serving Suggestions: Alongside a shame offering, or with panzanella salad (p. 32)

- Preheat a wood fire on a clean ash heap outside.

- Slaughter bull (at any entrance to the altar) by slitting throat, keeping hand on bull’s head in the presence of the Lord. Collect blood in a large bowl.

- After bringing bowl into your kitchen, dip two fingers into blood and sprinkle the ground seven times, taking care not to splash the curtain of your shrine.

- Apply a thin coat of blood to the altar (blood should coat the surface but not pool).

- Pour remaining blood at the base of the altar of burnt offering, or reserve for later use.

- Remove all fat from the bull, taking special care to remove fat surrounding the entrails, the loins, the kidneys, and the protuberance of the liver (removal of the entire kidneys is also fine). Burn fat on the altar as an offering, taking care to waft smoke upward toward heaven (guilt should begin to lift, too).

- Take the hide, the flesh, the head, the legs, the entrails, and the dung of the bull to the ash heap outside of camp. Burn it all in the wood fire until only ash is left.

“And Moses took some of the anointing oil and some of the blood that was on the altar and sprinkled it upon Aaron and upon his vestments, and also upon his sons and upon their vestments. Thus he consecrated Aaron and his vestments, and also his sons and their vestments.” —Leviticus 8:30

TZAV (“Command”)

Leviticus 6:1–8:36

Making sacrifices: the lord breaks down the details of sacrificial procedures for Moses to relay to Aaron and the priests. The critical issues of how long a burnt offering should last, what the priest should wear, and where the waste should be disposed of are explored. Moses is also instructed to ensure that the altar fire burns perpetually.

Procedures for sin offerings, guilt offerings, sacrifices of well-being, and meal offerings are also clarified, including exactly how much the priests can keep to eat themselves.

The ordination of the priests

Moses invites the entire community to assemble at the entrance of the Tent of Meeting with the priests, their clothing, anointing oil, a bull for sin offering, two rams, and a basket of unleavened bread.

During the ceremony Moses motions Aaron to step forward, then washes and dresses him as the Lord commanded. He takes the oil and uses it to consecrate the Tabernacle by sprinkling it on the altar before pouring some on Aaron’s head. After that, he dresses Aaron’s sons, who then help Moses pull the bull and rams to slaughter to consecrate the altar. Moses pours oil and blood on the priests’ clothing and concludes the ceremony by ordering them to remain in the Tent for seven days to complete their ordination.

Rachel Levin

I am only a few lines into the Torah portion that is Tzav and my eyes have already glazed over. Burnt offerings, linen raiment with linen breeches, ashes, vestments, smoke, fat, flour, fire. The details are exhausting, and I have yet to reach verse seven.

I think of stopping, but I have been assigned to write about this passage, and I am at my core the dutiful oldest daughter of a rabbi, a follower of directions. So I begin again, and that is when I notice him—a kindred responsible older sibling. It is Aaron, the brother called in to speak to Pharaoh for Moses, the one left to deal with a bunch of complaining Israelites when his younger sibling climbed up a mountain for forty days.

Here he is being given a new task; he is to become a priest. Tzav, I now see, is Aaron’s instruction manual, a ninety-seven-verse “to do” list dictated by God via Moses: Prepare flour on a griddle, divide meals into morning and evening portions, eat the leftovers of a sin offering. The directives are endless, the prescriptions exact. Yet Aaron does not complain once. In fact, throughout the entire Torah portion, Aaron does not utter a single word.

I am irritated for him.

As kids, my sisters and I promised one another that we would never become rabbis. Being a rabbi’s daughters had taken its toll on us—the seemingly endless “short” stops at the hospital on our way to dinner; comments of praise or derision about our father, which somehow seemed equally appropriate to share with his children; couches re-covered with a mistaken fabric but not able to be returned because they were done as a favor by a congregant. Yes I complained, but I also understood that this job of modern priest required offerings to be made morning and evening—that when our portion was the leftovers, we could not be picky.

My father, who shares his Hebrew name with Moses, not Aaron, was bound to his duties, but not so easily compliant. He chafed at being told what to do. He had his own creative approach to the rabbinate and saw his job as interpreting tradition in a way that was relevant and less about how things should be done. This meant that at a young age, I already knew about disgruntled synagogue presidents, split board votes, and what it meant to leave a synagogue with half the congregation to start one of your own. Around that time my mother moved to Arizona. Being the rabbi’s wife had taken its toll on her as well.

These old memories return as I read Aaron’s new job description, and I feel suddenly that this time, someone must speak for Aaron, must say what he himself does not, cannot, say. “Wait, God,” I call out. “I OBJECT. This new duty may be what is needed for the people, but what about Aaron? What of his children, his sons, who will also be forced to be priests?”

I have read ahead and know how the story will end: Two of Aaron’s sons will get too close to the fire when making an offering and will be consumed by flames. The sacrificers will become the sacrificed.

And yet, years later I am in Jerusalem at a dinner party, sitting on one end of a meticulously set table with thirty other guests. I suddenly notice a woman staring at me. She calls out, “Are you Martin Levin’s daughter?” Yes, I nod. Knife to wineglass, she silences the other conversations. “Listen,” she says. “I have a story to tell.” The story is of her son who is mentally disabled and how one morning, many years ago in synagogue, a rabbi gave her son a spur-of-the-moment bar mitzvah, something she had never thought possible. The rabbi called him up to the Torah and then led the entire congregation in dancing so joyous that it spilled out into the street. The congregation was celebrating her son, welcoming him as a full member of the community. “I will never forget what your father did for my family,” she says. Suddenly, she is crying and I am crying, too.

I have seen through the years how rabbis have special access to people because they are present when people are at their most joyous, most vulnerable, most pained, most in need of hope. My father knows that in these moments, there is possibility, and that has always been more than enough for him.

I whisper through the letters of the text, “Was that enough for you, Aaron?” And I wait.

“You shall not eat of their flesh or touch their carcasses; they are unclean for you.” —Leviticus 11:8

SH’MINI (“Eighth”)

Leviticus 9:1–11:47

It’s a dramatic appearance. eight days later, Moses convenes Aaron, his sons, and Israel’s elders, and commands them to arrange a complicated series of sacrifices involving a ram, a he-goat, an ox, some calves, and a meal offering.

The entire Israelite tribe assembles as Aaron goes to work amid the blood, organs, and smoke of the sacrifices. As he raises his arms to bless the people, the Lord appears in the form of fire, which bursts forth to consume the burnt offering. At the sight of this spectacle, the Israelites scream, fall forward, and bow down to the ground.

Aaron’s sons Nadab and Abihu set a fire and load it with incense to make an offering that God has not commanded. The Lord sets them on fire, burning them to death in an instant. Moses has to explain to Aaron that God meant it when speaking these words:

“Through those near to Me I show Myself holy,

And gain glory before all the people.”

Aaron remains silent.

Moses instructs Aaron’s cousins Mishael and Elzaphan to dispose of the burned bodies and warns Aaron and his family against following the traditional mourning ritual; if they tear their clothes or bare their heads, they will be struck down. The Lord takes a moment to prohibit Aaron and the priests from drinking alcohol before they enter the Tent of Meeting; they must be able to distinguish between the holy and the profane. The sacrifices then continue.

The birth of kosher

God fills Moses and Aaron in on the details of kosher food. The Israelites are allowed to eat any animal that has real hooves, and that chews the cud. Camels, a hare-like animal called daman, and swine are expressly prohibited. Any fish can be eaten if it has fins and scales.

Birds of prey, including the eagle, vulture, black vulture, hawks, and falcons, are off-limits. Ravens, nighthawks, ostriches, seagulls, little owls, great owls, white owls, cormorants, pelicans, bustards, storks, herons, hoopoes, and bats are prohibited.

All winged insects that walk are considered an abomination, though locusts, crickets, and grasshoppers are permitted.

A detailed list of animals deemed unclean is offered; it includes every beast that does not chew the cud or walk on paws. Anyone who carries the carcasses remains unclean until the evening and will have to wash their clothing.

God wraps up the legislation by reminding them of the intention behind the laws, declaring, “You shall be holy, for I am holy.” It becomes the Israelites’ task to distinguish between living things that can be eaten and those that cannot.

David Sax

Okay, this all seems pretty straightforward.

No pigs, shrimp, oysters, or mussels. Steer clear of the baby goats boiled in their mother’s milk, not to mention eels and sharks, crocodiles and geckos, hawks and vultures, and the rock badger (and I’m guessing that You’re also implying all other badgers as well).

Now, here’s a genuine product that’s clearly on Your hit list: Baconnaise, a spreadable mayonnaise, touted as a condiment and dressing, that tastes like the salted belly fat of the cloven-footed, hoof-parted, non-cud-chewing swine that are clearly verboten (right there in clause seven). It’s made by J&D’s, a food company based in Seattle whose slogan proclaims, “Everything Should Taste Like Bacon,” and it works to fulfill that commandment with products like bacon salt, bacon popcorn, bacon gravy, bacon lip balm, and bacon-flavored envelopes (called MMMMMMvelopes).

Sounds like treif city to me. Cue the fire, bring on the brimstone.

Wait, it’s kosher? Certified by the Orthodox Union to be consumed with meat, dairy, and parve foods? Seriously?

Okay, but how about the belly-crawling shellfish buffet offered by the idolaters at Dyna-Sea: crab salad and lobster rolls fit for a Kennebunkport summer’s lunch, and pink shrimp curled around a martini glass, mocking You from their horseradish-spiked red cocktail sauce, colored the very fire of hell they’re surely destined for.

Kosher, too? Certified by Kof-K for consumption with all foods. Oh, come on!

For close to three thousand years, Your chosen people have largely followed the dietary laws, avoiding the unclean creatures, making delicious brisket out of the clean ones, all while pretending You never really mentioned the whole edible-insects thing (locusts, crickets, and grasshoppers are perfectly kosher, because they have jointed legs, though the fried-cricket market of Crown Heights, Brooklyn, has yet to take off).

Then, in the mid-twentieth century, some among Your faithful realized that the devout were deprived, and, like Soviets trading a month’s supply of toilet paper for a pair of Levi’s, they would pay handsomely for the illusion of transgression wrapped in the legal safe ground of kosher certification.

“Look,” these people say, “it’s certified, within the letter of the law, kosher as a matzo. What’s the harm in eating a Whopper at the kosher Burger King in Costa Rica, or McNuggets at one of several kosher McDonald’s in Israel? If eating a Reuben sandwich with kosher corned beef and a slice of soy-based cheese was a sin, wouldn’t that be there in the Sh’mini? Wouldn’t there be a clause saying that we shall not eat foods that pretend to be unclean, even though they aren’t?”

Decades from now, a bar mitzvah buffet at a kosher banquet hall will resemble a Roman feast, once the tempeh tipping point is breached and test-tube experiments with embryonic protein cultures yield remarkably tasty kosher animal flesh. We’ll bypass the mock shrimp scampi wrapped in mock bacon, and head straight for the mock alligator jambalaya, mock eagle-egg sliders, and the pièce de résistance, an entire roast mock suckling pig, apple and all, carved with great flourish, in an act of legally certified, morally questionable mockery that the devout will eat with a greedy ferocity, grease painting their lips, as they turn to a shocked-looking elderly relative and say:

“Don’t worry, it’s perfectly kosher.”

“When a person has on the skin of his body a swelling, a rash, or a discoloration, and it develops into a scaly affection on the skin of his body, it shall be reported to Aaron, the priest, or to one of his sons, the priests.” —Leviticus 13:2

TAZRI·A (“She conceives”)

Leviticus 12:1–13:59

The lord’s next briefing revolves around the rules of purity. Moses learns that a woman is considered unclean for seven days after birthing a male, remaining in a state of “blood purification” for thirty-three days, during which time she cannot touch anything holy or enter the sanctuary. In the case of the birth of a daughter, however, the blood purification period is much longer, stretching to sixty-six days.

Upon concluding this blood purification process, the mother has to present the priest with a young lamb for a burnt offering and a pigeon or turtledove for a sin offering. Once the priest makes these two offerings on her behalf, the mother will be considered clean.

Monitoring the swollen

The Lord shows Moses and Aaron how to cope with bodily swellings and rashes. Priests are to perform an examination of the offending area and follow God’s detailed procedures to determine whether the patient is merely unclean or in need of isolation.

When a burn victim is examined, the priest has to inspect the depth of the wound and its coloring to determine whether the scarring is unclean. The same procedure has to be followed by those suffering from a disease of the head or beard.

Anyone found to be suffering from skin infections is to dwell outside the camp and have his clothes torn, head bared, and mouth covered while announcing himself with a shout of warning: “Unclean! Unclean!”

If a similar scaly infection erupts like a mold on wool or linen fabric, the priest shall determine if it can merely be washed or if burning is necessary.

Jamie Glassman

tinea cru-ris [kroo r-is], (noun), (medical). A dermatophyte fungal infection, or ringworm, involving especially the groin region in any sex, though more often seen in teenage males. Also known as eczema marginatum or (colloquial) crotch itch, crotch rot, gym itch, jock itch, jock rot, or in Budapest in 1989, scrot rot.

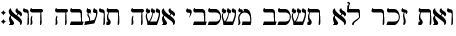

Whenever I read a portion of the Tanakh translated into English, I am taken back to my days as a twelve-year-old boy in Liverpool studying for my bar mitzvah.

This was the moment when I was to become part of the Jewish religion, with its thousands of years of tradition and its code of ethics that had survived numerous catastrophes.

After months of learning, practice, and nerves, it hadn’t crossed my mind to translate the words I would be singing to my local Hebrew congregation. I had just assumed that the words that I would sing would surely resonate and move me.

I can remember the moment my heart sank when I discovered that my parashah—a section from Exodus known as Mishpatim—was a long list of laws about the treatment of slaves and what to do with your neighbor’s lost ox should you see it wandering.

But I pity any poor twelve-year-old child who is saddled with this portion, Tazri·a, and reads it for the first time. It is a list of dos and don’ts for any leprosy sufferer. Could there be any less meaningful chunk of the Bible?

Things like When a person has on the skin of his body a swelling, a rash, or a discoloration that develops into a scaly or leprous affliction on the skin of his body, he shall present himself to the priest.

Or, If a white swelling streaked with red develops where the inflammation was, he shall present himself to the priest. The person with a leprous affliction, his clothes shall be rent and burnt, and he shall call out, “Unclean! Unclean!”

Surely there can be no more proof of the irrelevance of the Bible to our modern lives than this parashah.

That is unless you consider Maimonides’ thoughts on Tazri·a. A twelfth-century Jewish philosopher—you may know him as Rambam—Maimonides broadened this parashah into one of the most important lessons any teenage boy could ever learn.

When the Bible says “leprosy,” he wrote, think of it as any fungal infection.

The author attempts to sanitize his underwear in Budapest, 1989.

I learned Rambam’s lesson the hard way. Aged eighteen, I was traveling around Europe with a monthlong rail pass and two unfortunate friends.

Unfortunate because they would have to share train carriages, hotel rooms, and a tent with an overweight young man with a very serious case of tinea cruris.

Long walks on sweltering summer days through Europe’s great capitals with inappropriate polyester clothing might not have been what Maimonides had in mind, but the result was the same.

A mixture of stoicism and pride stopped me from seeing a doctor in a country where I knew only a smattering of the local language, so I walked through the streets of Paris and Rome like John Wayne after three weeks riding on the plains.

A fellow traveler attempts to scrape off the affliction in Padua, Italy.

The affliction was not without its benefits. There was some tender mercy on the long, crowded night train to Budapest, when it was impossible to get the much coveted banquette compartment in which third-class passengers might catch some sleep. That is, until I walked in stinking of rotting flesh, causing the carriage to empty within minutes. No sooner had the last bunch of young Euro lovelies fled the compartment than the choice of banquettes was ours.

Rambam didn’t say this, but I have added my own level of interpretation to the great scholar of Cordoba’s. Instead of a “priest,” perhaps the parashah should say a “pharmacist.” For in the back streets of Budapest my pain outweighed my shame when I limped into a local pharmacy and tried to mime my condition to the old man behind the counter.

He spoke no more English than I did Hungarian, so I pointed to my crotch and waved a hand in front of my nose, letting him see the agony on my face as I made each step.

His diagnosis was immediate. “Scrot rot!” he proclaimed with a theatrical clap of his palms, and he handed me a cream that cost me a few forints.

After days of suffering, just one application of his wondrous cream and my “leprosy” had gone.

So Tarzi·a is proof of the great wisdom of the Bible across continents and millennia, for this sufferer went to the priest/pharmacist and exclaimed, “I am Unclean! I am Unclean!” and an ointment was procured and the priest/pharmacist did make him clean once more.

And that night, the offending polyester shorts did warm us as they were tossed upon the fire.

If you know of any bar mitzvah boy or any young man in his teens about to embark on a long and possibly sweaty journey, I urge you to point him in the direction of Tazri·a. For there can be no greater lesson for a young man of this age.

Tell him that if he should experience a swelling, a rash, or a discoloration that develops into a scaly or leprous affection on the skin of his body, he should wash, dry, and air the affected area as often as possible, together with a generous application of a clotrimazole antifungal cream, available in any pharmacy, in any city in the world.

“This shall be the ritual for a leper at the time that he is to be cleansed.” —Leviticus 14:2

M’TZORA (“Being diseased”)

Leviticus 14:1–15:33

The scapegoating of the bird: the lord explains to Moses how a leprous or “skin-blanched” patient should be cleansed. The priest is to visit the diseased person outside the camp. If the infection appears to have cleared up, the priest is to take two live, pure birds, cedar wood, crimson stuff, and hyssop. One bird shall be killed, and the other is to be dipped in a mixture of bird blood and the other ingredients. After sprinkling the potion on the patient, the surviving bird is to be let free. The sick person shall wash his clothing, shave off all his hair, bathe, and then be deemed clean.

Once back in camp, the individual must remain outside his tent for seven days, and then shave off all his body hair again, wash his clothing, and bathe before being declared clean. The next day he shall make a series of sacrifices, in the course of which the priest shall dab oil on the head of the cleansed Israelite.

Home improvement

The Lord then teaches Moses and Aaron how to cope with the case of a mold-infected house in Canaan. The home is to be evacuated before the priest enters. If the priest identifies green or reddish streaks penetrating the wall, the house shall be closed up for seven days. If the infection continues to spread, the contaminated stone has to be ripped out and cast outside of the city. The rest of the house is to be thoroughly scraped and replastered. If the disease still remains, the house must be torn down and the debris discarded outside the city.

Discharged

The Lord then briefs the brothers on the tender subject of genital discharge, which is considered unclean. Not only is the infected man to wash his clothing and bedding, but anyone he may have spat on has to do likewise, and any earthen vessel he touched has to be broken. After seven days, the infected individual shall bathe and offer two birds as a sin offering.

A gentleman who has experienced an emission of semen is to bathe but still remains unclean until the evening. If he has enjoyed sexual relations with a woman, they both will be considered unclean until the evening. A menstruating woman is considered impure for seven days. Anyone who touches her will be unclean until the evening, unless it is a man enjoying sexual relations with her, in which case he too is considered unclean for seven days. A woman who bleeds when not menstruating must be monitored; she is considered unclean as long as her discharge lasts.

God concludes by warning Moses to make sure that the Israelites guard against disease, so they do not die by defiling the Tabernacle.

Tim Samuels

Prescription

Patient: Mr. Levite

Medication to be collected by: Moses (Levite family friend)

Condition: Patient claims to be suffering from leprosy. Closer examination reveals merely patches of dry skin around the elbows and knees, and some flakiness around the nose. Probably caused by excessive time recently spent wandering around the wilderness without adequate moisturization. However, patient was insistent on full course of treatment, lest the condition develop into full-blown lesions.

Treatment: When the symptoms appear to be improving, gather two clean birds (living), cedar wood, something crimson, and a sprig of hyssop. Slaughter one bird, and dip the other bird in the blood, cedar, crimson, and hyssop. Sprinkle the blood on the affected areas seven times and set the living bird free. Wash all clothes, shave off hair, take a long bath, and sleep away from home for seven days. On the seventh day, bathe, and shave off all hair (again), including eyebrows and beard. The following day, sacrifice a lamb and put blood and oil on the right ear, right thumb, and right big toe. If insurance policy does not cover cost of the lamb, Medicare turtledoves or pigeons can be used instead. (All lambs free of charge in Europe, Canada, and other socialist enclaves.)

Not to be taken with: The following may exacerbate the condition: idol worship, unchastity, bodily violence, profaning God, blasphemy, robbery, usurping a dignity, overweening pride, evil speech, and casting an evil eye. Haughtiness and general immorality are best avoided, too.

Long-term side effects: Prolonged obsession with obscure cleansing rituals from 1440 b.c. onward could lead to endemic hypochondria among future generations and an absurd though comforting overrepresentation among medical professionals.

“Do not lie with a male as one lies with a woman; it is an abhorrence.” —Leviticus 18:22

AHAREI MOT (“After death”)

Leviticus 16:1–18:30

The long-suffering brother. after the death of Aaron’s two sons, the Lord warns Moses to forbid his brother from freely entering the Tabernacle’s inner sanctuary, known as the Holy of Holies. Exposure to God’s presence will kill him, unless he is appropriately clothed and has presented a complicated series of sin offerings and burnt offerings, then laid his hands on the head of a goat and dispatched it into the wilderness to carry away the symbolic sins of the Israelites.

God then commands Moses to make sure Aaron sacrifices only sheep and goats at the Tent of Meeting. Anyone making sacrifices elsewhere is to be cut off from the people. In addition, anyone eating an animal carcass is to be deemed unclean until he has undergone the purification process.

The Naked Truth

God then makes clear that Moses must understand that the norms of Egyptian society no longer apply to the Israelites. They are to be careful about nudity and avoid seeing many of their relatives naked, including their father, mother, father’s wife, sister, half sister, granddaughter, aunt, uncle, daughter-in-law, and sister-in-law. A man is also to avoid marrying both a mother and her daughter or granddaughter, or a woman and her sister in the other’s lifetime. A man is also forbidden from enjoying sexual relations with a woman during her period, or with his neighbor’s wife. He is also commanded to avoid offering his offspring to a foreign god, or committing bestiality.

An Israelite is to consider defiling himself as grave an act as defiling the land. The tribes who preceded the Israelites may have committed abhorrent acts, but if those practices are maintained, the land will spit them out, too. Those who commit repulsive acts must be cut off from their people.

Amichai Lau-Lavie

becoming a man: my bar mitzvah speech thirty years later

I grew up Orthodox in Israel. By the time of my bar mitzvah—in April 1982—I was living in New York City, a sweet kid in a polyester suit. A little on the chubby side, perhaps. My dark blond mop of hair covered a pimpled forehead.

Being Orthodox had its advantages. Chanting my bar mitzvah portion was no problem. I rattled it off with ease. The problem was the speech. There was so much I wanted to say, but my English wasn’t good enough, and anyway, my speech had been written for me by my uncle, a renowned rabbi, who gave me a tired presentation expounding on the laws of charity.

Thirty years on, I would like to think that if the choice had been mine, and I had been able to summon the courage, this is the speech I would have delivered at the Fifth Avenue Synagogue in Manhattan.

As I write it, I imagine my forty-three-year-old self as a man in a black suit with a trim beard, standing directly behind that chubby bar mitzvah boy and visible to him alone.

Esteemed Rabbis, My Dear Parents, Family, and Friends:

Shabbat Shalom.

Thank you for coming to celebrate with me on this day on which I become a man. Many of you have traveled very far to get here. My parents and I appreciate it very much.

My bar mitzvah portion, Aharei Mot, is about laws and limitations. Laws, I understand, are necessary, because without them things go wrong, and people can get hurt. The portion begins with the reminder of what had happened to the two sons of Aaron, the high priest, and how they died by a “strange fire” because they did not observe the law, and were not careful enough when they entered the holy Tent of Meeting.

There are many different kinds of laws in this portion. These laws, I was taught, were given to us by God so that each of us can live a holy life, as part of a bigger, healthy society.

I started learning how to chant my Torah portion two years ago, back when we were still in Israel, from a cassette tape. I played it over and over again to memorize the verses by heart. At first, I didn’t think about what the words meant.

But over time I started paying more attention, and I began to wonder about the meaning of some of these laws, especially the ones about not seeing people naked.

There is a list, in this portion, of relatives that you are not supposed to see naked.

I figured out that “seeing someone naked” was a euphemism—a biblical way to talk about “having sex.” But I couldn’t understand why some relatives are on the list and some aren’t. And I had other questions, also, about some of the other laws.

My teacher, Rabbi Motti, didn’t want to talk about this too much. He said I’d understand when I am more grown up. When I become a man.

And I guess that day is today.

I don’t know if I’m as grown up as my teacher intended, and if I’m really already a man, but as I turn thirteen today, I think I’m just old enough to ask you all a question about these laws, and about one of them in particular that I’ve been thinking a lot about.

The room is stilled. My mother, up in the women’s balcony, is looking at me with a grave, strange look. My father, in the front row, turns to my uncle, who is seated next to him, and whispers something in his ear. The uncle shakes his head, confused.

After the list of relatives one is not supposed to see naked there are a few other laws that describe prohibited sexual behaviors. One of the laws forbids sex with animals. Another of the laws prohibits sexual relations between men. It’s called an abomination. And whoever does it can be punished by death.

Silence.

I’m sorry if this is weird, and maybe neither appropriate nor the speech you expected me to make today. But a few months ago, when we walked home from this synagogue, I asked my father what it means to be a man, and he told me that to be a man is to be honest and not be afraid of the truth.

And the truth is that I’ve been thinking a lot about this law, and it makes me afraid and ashamed to think about it and to talk about it, but it also makes me angry and confused.

I know it’s wrong to question God and the Torah, and maybe I’m too young to understand. But I don’t think that the law about abomination is fair, and I don’t think that people who break it deserve to die.

Today, you say, I am a man. But in fact I think that it already happened.

I think that I became a man almost a year ago, when I kissed for the first time, and felt like a grown-up.

I kissed another boy, a friend of mine, a friend I love.

It made us both afraid and nervous, but it didn’t feel dirty, or wrong, or like an abomination, whatever that is. It felt holy, whatever that is. It felt right.

DON’T LOOK UP. DON’T LOOK UP. My mouth is dry. My heart beats faster than it ever has. I am aware my life will never be the same again. I read on.

I am not an abomination. I don’t deserve to die because of whom I love.

You are all looking at me now, and it’s not pleasant, but I’ve held this secret, this abomination in my stomach, long enough.

If today I am a man, then on this day I tell the truth and face it, like a man. And you, who came from near and far, if you really love me, will love me still, I hope, just the way I am.

I know the Torah says it’s wrong.

I know it’s disappointing to you, my parents and siblings, relatives, friends.

But maybe the Torah does not mean what I’m feeling, because I don’t think—I don’t believe—that God thinks I am dirty, or sinning, or an abomination. Because isn’t that how God created me, in God’s own image, just the way I am?

Today I become a man, and I am who I am, with all of my questions, and doubts, and hard choices, and truths.

I think that’s what becoming a man is all about.

I want to thank you, my parents, for helping me so much in preparing for today, and for being the best parents possible. I’m sorry if I surprised you now, but I hope that you understand. Thank you to my brothers, and my sister, for coming all the way from Israel for this occasion and for always being there for me.

My family are all looking at the floor.

Thank you for listening, and for joining me on this most important day of my life.

Shabbat Shalom.

I close the folder and dare to look up. Will somebody say something? Someone please hug me. My mother is crying. My father still stares down. Don’t hate me. Please say something.

And there I stand, thirty years later, placing a hand on my thirteen-year-old self’s shoulder and whispering, softly, “It’s going to be all right.”

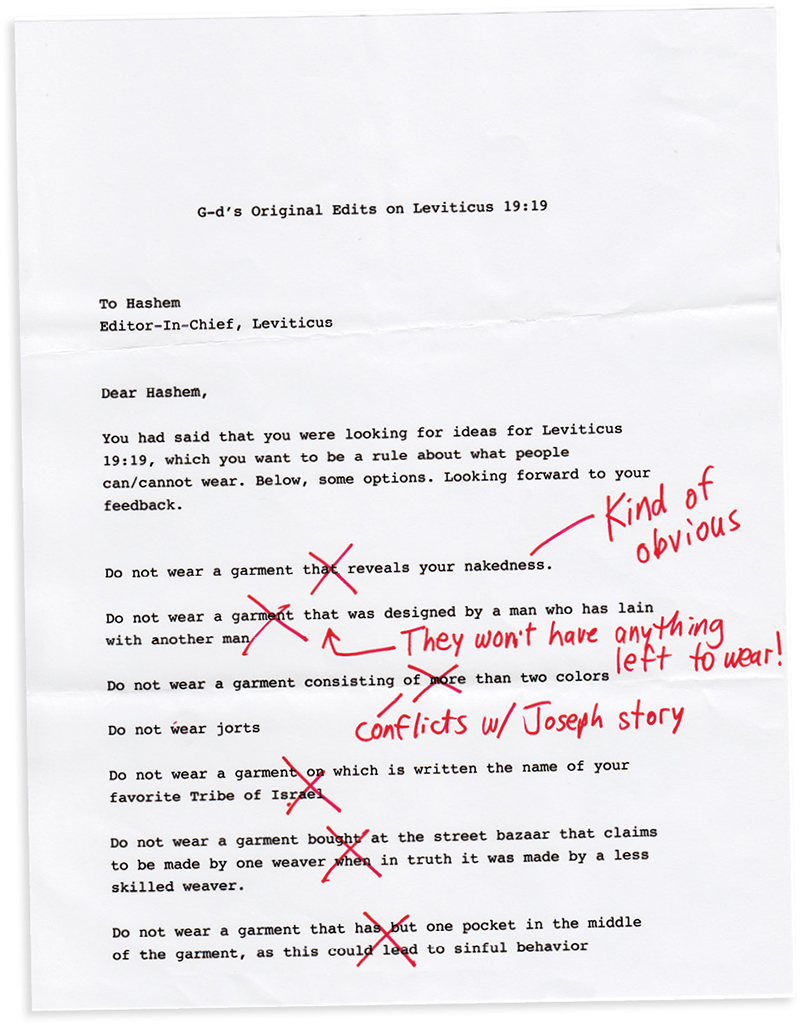

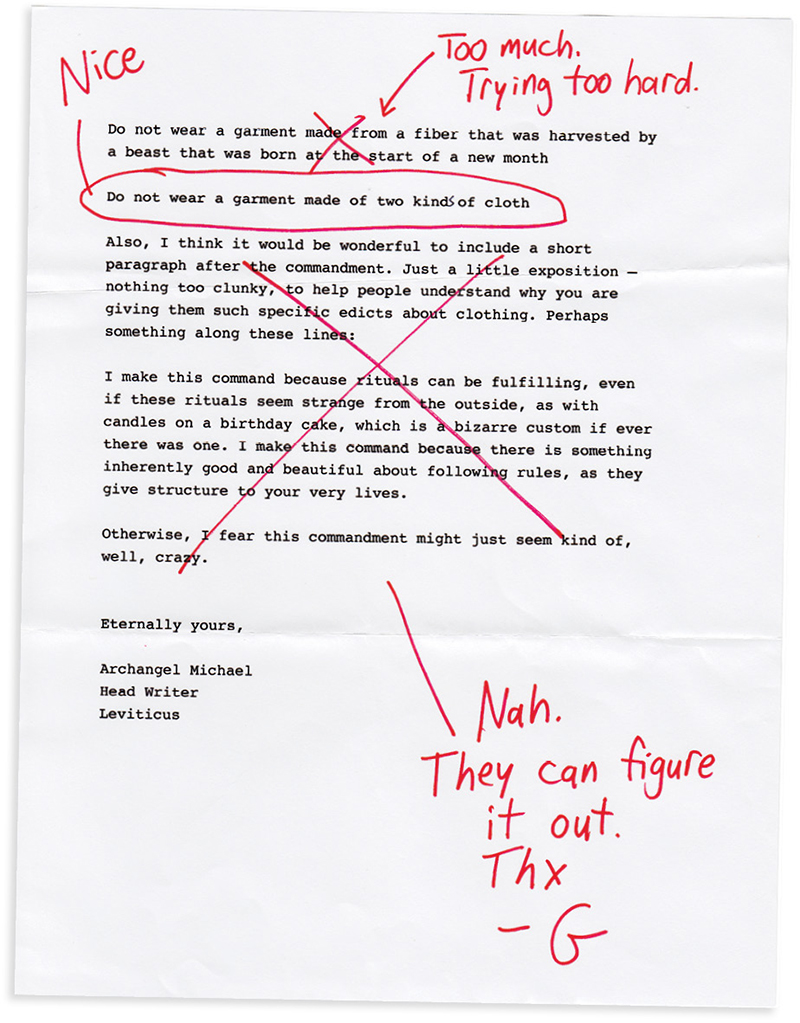

“You shall not let your cattle mate with a different kind; you shall not sow your field with two kinds of seed; you shall not put on cloth from a mixture of two kinds of material.” —Leviticus 19:19

K’DOSHIM (“Holy ones”)

Leviticus 19:1–20:27

The holy lifestyle: the lord outlines the ways the Israelites are to pursue a holy life in the style of God, based around a catalog of loosely connected behaviors, starting with the basics—honoring parents, keeping the Sabbath, shunning idols, and following sacrifice protocol.

Appropriate harvesting techniques are then defined. Israelites are to leave the edges of their fields unharvested, and in the vineyards, fallen fruit is to be left ungathered. The intention of both laws is the same—to create a food supply for the poor.

Stealing, fraud, robbery, deceitful dealings, and withholding wages are prohibited. Ditto for making a false oath in God’s name or swearing profanely.

Insulting the deaf or intentionally taking advantage of the blind is forbidden.

Fair judgment is expected. Decisions shall neither intentionally favor the poor nor corruptly support the rich. No one shall benefit from the suffering of their fellow countrymen.

One Israelite can accuse another, but not falsely. Taking vengeance or bearing grudges is not permitted. They are to love others in the same way they love themselves.

Odd combinations are not to be fostered: Different beasts shall not be mated. Two different kinds of seeds shall not be sown in the same field. Two different kinds of material shall not be woven into a piece of cloth.

If a man has sexual relations with another man’s slave, he will not be put to death as would be the case if it was someone else’s wife, because the woman is not free. A sin offering will suffice to rectify the situation.

Once they enter the land, any new tree that is planted cannot be harvested for three years. In the fourth year, the first fruit must be offered to the Lord before the rest can be eaten.

A rapid round of prohibited acts is then set out:

No animal can be eaten along with its blood.

Soothsaying is outlawed.

Men are not to shave off side-growths from their heads or beards.

No tattoos or gashes can be made in the flesh.

Daughters cannot be turned into whores, thus creating a depraved land.

Sabbaths and the sanctuary must be revered.

Ghosts cannot be engaged with.

The old have to be respected.

Foreigners are to be afforded the same rights as citizens, because the Israelites were once seen as foreigners in Egypt.

Merchants cannot employ false measures and weights.

Punishment . . . and reward

God proceeds to stipulate a slew of punishments to Moses:

Any Israelite or visitor worshipping false foreign gods like Molech shall be punished with death by stoning.

A person who communes with ghosts shall be cut off from the people.

The death penalty is prescribed for those who insult their parents, commit adultery, or lie with their father’s wife or daughter-in-law. If a man lies with another man, it is to be considered an “abhorrent thing”; they both will be put to death. If a man marries both mother and daughter, all three shall be burned to death. If man or woman lies with a beast, both human and animal shall be killed.

Incest—marrying a sister or half sister—is not permitted. Those who indulge in it shall be cut off from their people. A man who lies with a woman when she is unwell will suffer the same fate. Men shall not lie with their aunts or marry their brother’s wife. Those who do are doomed to die childless.

The Israelites are specifically instructed to avoid the norms of the Canaanites, whom God is poised to drive out of Canaan as a result of their abhorrent behavior. God reminds Moses that the land will soon flow with the promised milk and honey. The Israelites are to be set apart from other people, and in the same way, they are to set apart the clean beast from the unclean and to carry on as a holy people.

A. J. Jacobs

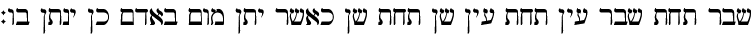

“Fracture for fracture, eye for eye, tooth for tooth, the injury he inflicted on another shall be inflicted on him.” —Leviticus 24:20

EMOR (“Speak”)

Leviticus 21:1–24:23

Priestly rules: the lord tells moses to make sure the priests know not to come into contact with a dead body unless the deceased is a close relative: a mother, father, son, daughter, brother, or a virgin sister who remained unmarried.

Priests are to follow a series of rules. They are not to cut the sides of their beards or make gashes in their own flesh. They cannot bare their heads or tear their clothes. Nor are they to take the name of God in vain.

When it comes to marriage, it is imperative that the priest marry a virgin. Because of this, priests can never marry a prostitute or divorcee. If a priest’s daughter becomes a prostitute, she will have defiled her father and so must be burned to death.

If a priest’s son is blind or lame, a hunchback or a dwarf, or cursed by a growth on his eye, scurvy, or “crushed testes,” the son will no longer be qualified to make offerings by fire. The defect removes his ability to come behind the curtain to the altar and to enter places that have been sanctified by God.

If the priests are unclean, they are to avoid touching the sacrifices until they are clean again. A number of objects that can make a priest unclean are described, including a dead body, semen, or a “swarming thing.”

Non-priests are prohibited from eating donated offerings unless they are from the priests’ slaves, or a priest’s daughter who has been widowed and become dependent on her father again.

Sacrifice worthiness . . . plus the calendar revealed

A sacrifice must not be defective. Defects listed include animals that are blind or maimed or suffering from crushed testes. Offerings have to be at least eight days old, but no animal can be sacrificed alongside its young.

God then articulates the days that will be considered holy.

- No work shall be done on Sabbath, the seventh day.

- Passover will start on the fourteenth day of the first month and last seven days, with the first and last days considered sacred.

- A Harvest Festival will occur fifty days later.

- Rosh Hashana, on the first day of the seventh month, will be marked by complete rest and shofar blasts.

- Yom Kippur will be on the tenth day of the seventh month. Any person who does not participate will be cut off from his kin, and those who ignore the day and work shall be put to death.

- Sukkot, on the fifteenth day of the seventh month, will involve dwelling in huts for seven days and employing palm and citrus trees in celebration.

These are listed as the Lord’s sacred occasions in which sacrifices should be offered.

Moses is advised to make sure the Israelites bring clear oil to kindle the Temple lights and keep them burning. They also have to provide bread for the altar every Sabbath.

A story is then told of a man whose mother is Israelite and whose father is Egyptian. The man had a fight with another Israelite, during which he used God’s name in vain; the “half-Israelite” is placed in custody to await the Lord’s ruling. God commands that he be taken outside the camp and stoned before those who witnessed the blasphemy, and he is.

God commands that blasphemers be put to death, as well as murderers. An Israelite who kills another man’s beast has to make restitution. Those who maim others will have to suffer the same injury in return: fracture for fracture, eye for eye, tooth for a tooth.

Dana Adam Shapiro

We

I’ve been thumping the Bible

And thinking of truth

Of an eye for an eye

And a tooth for a tooth.

Of revenge, retribution

AYIN TACHAT AYIN,

That dish best served cold

Was it cooked on Mount Zion?

To wish for the murdering man to drop dead

Got me thinking of what Dr. Seuss might have said.

So I sat, then I stood.

Then I sat back and wondered

Of times when I’ve stumbled and bumbled and blundered,

Of times I’ve been too cool or too proud to say

That “I’m sorry,

I’m sorry for being that way.”

But it’s not just a lack of I’m sorrys that sway

Peaceful people to huff and to puff in that way

That we all know can lead to a POW!

Or a THWACK!

Or a monkey Velcro-ing itself to your back.

It’s the triumph of ego.

A hex laid upon us.

That need to get even

Or LEX TALIONIS.

Now think of the eye for the eye

And the tooth—

Why, it sounds so unfriendly,

It sounds so uncouth.

Though intended to moderate vengeance, instead

It makes people grow eyes in the back of their head.

But imagine if “eye” became “I”

As in: You

And if TOOTH became TRUTH.

Tell me, what would you do?

Yes, an I for an I

And some truths for some truces,

We’ll unplug the chairs

And unravel the nooses.

An eye for an eye equals blindness,

You’ll see,

But an I for an I

Makes for something called

We.

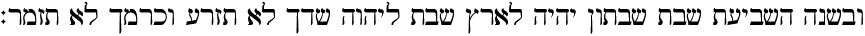

“But in the seventh year the land shall have a Sabbath of complete rest, a Sabbath of the Lord; you shall not sow your field or prune your vineyard.” —Leviticus 25:4

B’HAR (“On the Mount”)

Leviticus 25:1–26:2

The lord broaches the notion of a Sabbatical for the land with Moses. Every seven years, the fields are to be left unsown and the vine- yards untended, so the land can recuperate. In the year after the seventh Sabbatical, the fiftieth year, the Israelites are to celebrate a jubilee with a loud horn blast. The jubilee year is akin to a Sabbatical year where the land will lie fallow, but in addition, all property will revert to the possession of its original owners, unless it is an urban dwelling in a walled city.

Indebted

If an Israelite falls on such hard times that he has to borrow money, interest cannot be charged. If the Israelite is unable to repay the debt and has to offer his own services instead, he cannot be treated as a slave. He shall work as a hired laborer and be freed in the jubilee year, because no one Israelite can rule over another.

Mireille Silcoff

I liked my school, because my school was quiet. In retrospect it was also a dour place: The heavy shoes of rabbis and the stern heels of French teachers echoed through dark green hallways that smelled like old wet paper. This is not the sort of place a child would normally relish. More like something out of Pink Floyd’s The Wall.

But I liked it. You could hunker down there, between the pencil shavings and the monolithic walls of books with burgundy pleather covers. I believed I had a secret. It was one of those innately childish beliefs, like thinking that your voice is deeper than everyone else’s, because that’s how it sounds in your ears. My mother imagined I did well in school because I had smarts. But I knew my scholarly success as a third grader had nothing to do with intellect. It had to do with stillness. I liked sticking my head into something and then leaving it there for a while. It felt, somehow, homey.

This was not the sort of home my mother approved of. An active woman of Tel Aviv provenance, an Israeli folk dancer in both calling and profession, she held that life, the childhood phase of it in particular, was synonymous with movement. This meant that if any of my time was in her hands, it would most likely be spent in a leotard.

Witness: It’s 1981. I am eight years old. I am just minding my own business, reading a cereal box while eating its cereal for breakfast. My mother is playing a cassette of unspeakably bad Israeli folk music while reminding me of my week:

“Okay! Today, Monday! After school you have rhythmic gymnastics, Wednesday you have Broadway, Thursday you have modern dance, and Friday, danse ouverte.”

My mother knew that I was a hopeless dancer. But four days a week, she had her rehearsals, and they went late, and she needed somewhere to put me. She didn’t want me to be one of those sad kids with a key tied around my neck, sitting in a house, doing nothing. And I suppose in early 1980s Quebec, extracurriculars were limited. And so dance and dance and dance and dreaded open dance it was.

On some mornings, I pleaded with her to just let me come home after school, to the silent house. I would imagine the darkening at 4:00 p.m. in the Petits Anges dance studio with Gerry Laframboise, the rhythmic gymnastics instructor, who wore a black scoop-neck with chest hair sprouting forth, like a bearish Marcel Marceau, and I would feel bone tired: the overheated locker room; the running around in leg warmers with an unfurling ribbon on a stick (and for what purpose? this ribbon on a stick?); the hungry lineup for miniature boxes of hard raisins; the chattering car pool home.

In school, most of the books I had for my classes contained central sections of calligraphic-looking Hebrew writing framed by columns of smaller Hebrew writing. The school was always cold. You kept your head in your weekly Torah portion, the big writing, and then the small. You used the heat of your eight-year-old mind to make the blocks of text come apart.

I chose to write about this parashah—B’har, a far-from-exciting bit, largely about leap years in farming practice—because it is, even over anything in the big bang of B’reishit, the one I remember best from my primary school years.

This is because I took B’har out of the book and put it into my life. Children are capable of surprisingly lateral thinking. I thought, For every extended period of planting, the farmer gives the land a period to rest. God says the farmer has to, or everything will get too exhausted. The farmer does not plow, or dig, or sow, or prance about in French Canadian dance studios balancing ball on chest like a trained seal. The farmer, might, say, kick back in a cozy bedroom with a nice chapter book in a quiet, empty house at dusk.

There was no way I could have persuaded my mother to cut my extracurriculars by quoting Bible passages about taking breaks. So, God on my side, I began lying instead. One week I made my modern dance instructor sick, and the next Gerry Laframboise “canceled class.” The week after that I had a sudden headache for Broadway, and the week after that my mother may have understood something: I got a key, and it went around my neck. And sometimes, when I was sure I was alone, I danced like crazy in my bedroom.

“And if, for all that, you do not obey Me, I will go on to discipline you sevenfold for your sins.” —Leviticus 26:18

B’HUKKOTAI (“By my decrees”)

Leviticus 26:3–27:34

Reward! god reminds moses of the covenant. As long as it is maintained, God will sup- ply rain at the appropriate time and guarantee a bountiful harvest so the Israelites can eat their fill and dwell securely in their land.

Peace shall reign. The Israelites will not be threatened by either man or beast. All enemies will be put to the sword. Just five Israelites will be imbued with sufficient power to rout 100 of their enemies. One hundred can make ten thousand flee.

The Lord will ensure that the Israelites multiply, while residing in their midst.

And the punishment

However, if the Israelites do not maintain the covenant and keep the Lord’s commandments, misery will befall them. The Israelites will be beset by consumption and fever. They will sow their seed fruitlessly. Their enemies will dominate them. Their land will yield no produce. Wild beasts will kill their children and cattle. The Israelites will withdraw into their cities, yet an epidemic will run among them and their enemies will control them.

Hunger will set in, and they will be forced to cannibalize their sons and daughters. They will be scattered among the nations as their land becomes desolate and their cities ruined. The Israelites will be made so nervous that the sound of a leaf will make them flinch, and they will fall over though no one is pursuing them. They will rot in the lands of their enemies.

Those who survive will confess their guilt and the guilt of their fathers, and they will atone, and God will remember the covenant made with Isaac and with Abraham and will remember the land.

A costly vow

As an appendix, God affixes values for Israelites who want to consecrate or sanctify their lives to the Lord, or the lives of family members, as a ritual and voluntary act of dedication to God. The cost of consecration is set out as follows:

- 50 shekels of silver for a male aged 20–60 years old

- 30 shekels for a woman aged 20–60 years old

- 20 shekels for a boy aged 5–20 years old

- 10 shekels for a girl aged 5–20 years old

- 5 shekels for a boy aged 1 month to 5 years

- 3 shekels for a girl aged 1 month to 5 years

- 15 shekels for a man 60 years or over

- 10 shekels for a woman 60 years or over

If the person who wants to make a vow cannot afford the above sums, a priest is to fix a fair price.

Christopher Noxon