A lot has changed in windows since the Windows of a few years ago. If you’re feeling disoriented, firmly grasp a nearby stationary object and read the following breakdown.

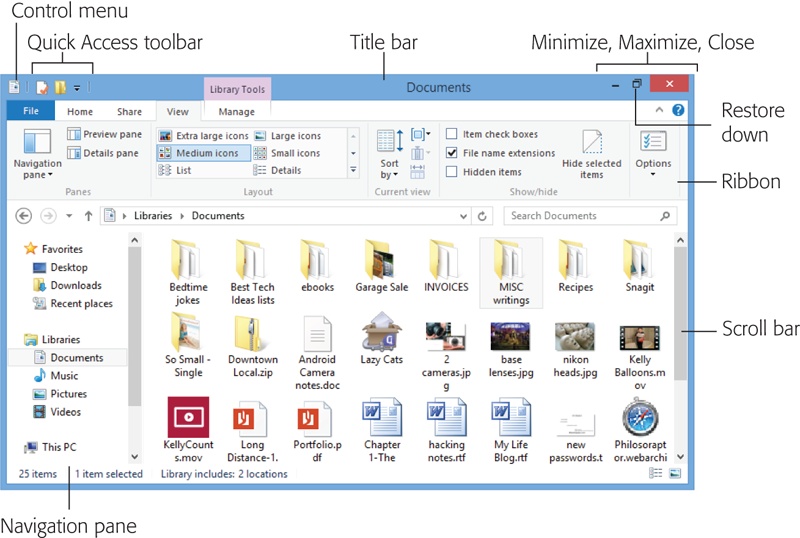

Here are the controls that appear on almost every window, whether in an application or in File Explorer (see Figure 6-4):

Control menu. This tiny icon sat in the upper-left corner of every Explorer window in Windows XP. It was invisible (but still functional) in Windows 7. And now it’s back.

In any case, the Control menu contains commands for sizing, moving, and closing the window. One example is the Move command. It turns your cursor into a four-headed arrow; at this point, you can move the window by dragging any part of it, even the middle. Why bother, since you can always just drag the top edge of a window to move it? Because sometimes, windows get dragged past the top of your screen. You can hit Alt+space to open the Control menu, type M to trigger the Move command, and then move the window by pressing the arrow keys (or by dragging any visible portion). When the window is where you want it, hit Enter to “let go,” or the Esc key to return the window to its original position.

Quick Access toolbar. New in Windows 8: You can dress up the left end of the title bar with tiny icons for functions you use a lot—like Undo, Properties, New Folder, and Rename. And how do you choose which of these commands show up? By turning them on and off in the Customize Quick Access Toolbar menu (

), which is always the last icon

in the Quick Access toolbar.

), which is always the last icon

in the Quick Access toolbar.Tip

As you can see in the

menu, the Quick Access toolbar doesn’t

have to appear in the title bar (although that is the position that

conserves screen space the best). You can also make it appear as

a thin horizontal strip below the Ribbon, where it’s not so

cluttered. Just choose—what else?—“Show below the

ribbon.”

menu, the Quick Access toolbar doesn’t

have to appear in the title bar (although that is the position that

conserves screen space the best). You can also make it appear as

a thin horizontal strip below the Ribbon, where it’s not so

cluttered. Just choose—what else?—“Show below the

ribbon.”Title bar. This big, fat top strip is a giant handle you can use to drag a window around. It also bears the name of the window or folder you’re examining.

Tip

The title bar offers two great shortcuts for maximizing a window, making it expand to fill your entire screen exactly as though you had clicked the Maximize button described below. Shortcut 1: Double-click the title bar. (Double-click it again to restore the window to its original size.) Shortcut 2: Drag the title bar up against the top of your monitor.

Ribbon. That massive, tall toolbar at the top of a File Explorer window is the Ribbon. It’s a dense collection of controls for the window you’re looking at. You can hide it, eliminate it, or learn to value it, as described in the next section of this chapter.

Navigation pane. Some form of this folder tree, a collapsible table of contents for your entire computer, has been part of Windows for years. It’s described on Navigation Pane.

Window edges. You can reshape a window by dragging any edge—even the very top. Position your cursor over any border until it turns into a double-headed arrow. Then drag inward or outward to make the window smaller or bigger. (To resize a full-screen window, click the Restore Down

button first.)

button first.)Minimize, Maximize, Restore Down. These three window-control buttons, at the top of every Windows window, cycle a window among its three modes—minimized, maximized, and restored, as described on the following pages.

Close button. Click the

button to close the window.

Keyboard shortcut: Press Alt+F4.

button to close the window.

Keyboard shortcut: Press Alt+F4.Tip

Isn’t it cool how the Minimize, Maximize, and Close buttons “darken up” when your cursor passes over them?

Actually, that’s not just a gimmick; it’s a cue that lets you know when the button is clickable. You might not otherwise realize, for example, that you can close, minimize, or maximize a background window without first bringing it forward. But when the background window’s Close box “glows dark,” you know.

Scroll bar. A scroll bar appears on the right side or bottom of the window if the window isn’t large enough to show all its contents.

A Windows window can cycle among three altered states.

A maximized window is one that fills the screen, edge to edge, so you can’t see anything behind it. It gets that way when you do one of these things:

Maximizing the window is an ideal arrangement when you’re surfing the Web or working on a document for hours at a stretch, since the largest possible window means the least possible scrolling.

Once you’ve maximized a window, you can restore it to its usual, free-floating state in any of these ways:

When you click a window’s Minimize

button ( ), the window gets out of your way. It

shrinks down into the form of a button on your taskbar at the

bottom of the screen. Minimizing a window is a great tactic when you want

to see what’s behind it. Keyboard shortcut:

), the window gets out of your way. It

shrinks down into the form of a button on your taskbar at the

bottom of the screen. Minimizing a window is a great tactic when you want

to see what’s behind it. Keyboard shortcut:

+

+  .

.

You can bring the window back, of course (it’d kind of be a bummer otherwise). Point to the taskbar button that represents that window’s program. For example, if you minimized an Explorer (desktop) window, point to the Explorer icon.

On the taskbar, the program’s button sprouts handy thumbnail miniatures of the minimized windows when you point to it without clicking. Click a window’s thumbnail to restore it to full size. (You can read more about this trick later in this chapter.)

Microsoft wants to make absolutely sure you’re never without some method of closing a window. It offers at least nine ways to do it:

Press Alt+F4. (This one’s worth memorizing. You’ll use it everywhere in Windows.)

Double-click the window’s upper-left corner.

Right-click the window’s taskbar button, and then choose Close from the shortcut menu.

Point to a taskbar button without clicking; thumbnail images of its windows appear. Point to a thumbnail; a

button appears in its upper-right corner.

Click it.

button appears in its upper-right corner.

Click it.Right-click the window’s title bar (top edge), and choose Close from the shortcut menu.

In an Explorer window, choose File→Close. That works in most other programs, too.

Quit the program you’re using, log off, or shut down the PC.

Be careful. In many programs, including Internet Explorer, closing the window also quits the program entirely.

Tip

If you see two  buttons in the upper-right corner of your

screen, then you’re probably using a program like Microsoft Excel.

It’s what Microsoft calls an MDI, or multiple document

interface program. It gives you a window within a

window. The outer window represents the application itself; the

inner one represents the particular document

you’re working on.

buttons in the upper-right corner of your

screen, then you’re probably using a program like Microsoft Excel.

It’s what Microsoft calls an MDI, or multiple document

interface program. It gives you a window within a

window. The outer window represents the application itself; the

inner one represents the particular document

you’re working on.

If you want to close one document before working on another, be careful to click the inner Close button. If you click the outer one, you’ll exit the entire program.

When you have multiple windows open on your screen, only one window is active, which affects how it works:

It’s in the foreground, in front of all other windows.

It’s the window that “hears” your keystrokes and mouse clicks.

Its Close button is red. (Background windows’ Close buttons are transparent or window-colored, at least until you point to them.)

As you would assume, clicking a background window brings it to the front.

And what if it’s so far back that you can’t even see it? That’s where Windows’s window-management tools come in; read on.

Tip

For quick access to the desktop, you can press

+D. Pressing that keystroke again brings all

the windows back to the screen exactly as they were.

+D. Pressing that keystroke again brings all

the windows back to the screen exactly as they were.

There’s a secret button that does the same thing when clicked or tapped, too. It’s the Show Desktop button—a tiny, skinny rectangle that occupies the farthest-right sliver of the taskbar. (It was there in Windows 7, too, but you could see it. Now you just have to know it’s there.)