You can’t paste a picture into your Web browser, and you can’t paste MIDI music into your desktop publishing program. But you can put graphics into your word processor, paste movies into your database, insert text into Photoshop, and combine a surprising variety of seemingly dissimilar kinds of data. And you can transfer text from Web pages, email messages, and word processing documents to other email and word processing files; in fact, that’s one of the most frequently performed tasks in all of computing.

Most experienced PC users have learned to quickly trigger the Cut, Copy, and Paste commands from the keyboard—without even thinking.

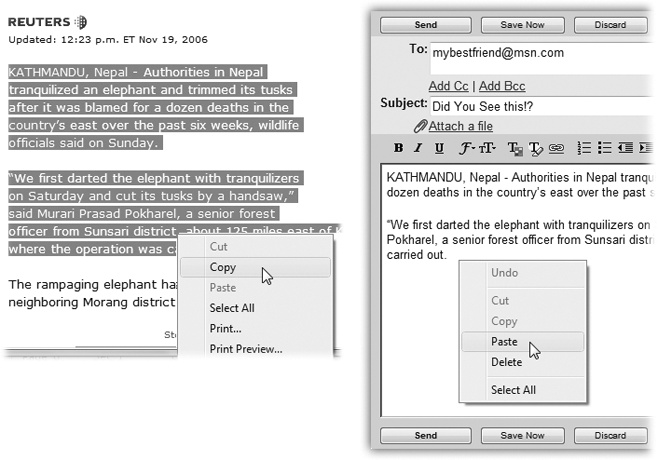

Bear in mind that you can cut and copy highlighted material in any of three ways. First, you can use the Cut and Copy commands in the Edit menu; second, you can press Ctrl+X (for Cut) or Ctrl+C (for Copy); and third, you can right-click the highlighted material and, from the shortcut menu, choose Cut or Copy (Figure 10-3).

Figure 10-3. Suppose you want to email some text from a Web page to a friend. Left: Start by dragging through it and then choosing Copy from the shortcut menu (or choosing Edit→Copy). Right: Now switch to your email program and paste it into an outgoing message.

When you do so, Windows memorizes the highlighted material, stashing it on an invisible Clipboard. If you choose Copy, nothing visible happens; if you choose Cut, the highlighted material disappears from the original document.

Pasting copied or cut material, once again, is something you can do either from a menu (choose Edit→Paste), from the shortcut menu (right-click and choose Paste), or from the keyboard (press Ctrl+V).

The most recently cut or copied material remains on your Clipboard even after you paste, making it possible to paste the same blob repeatedly. Such a trick can be useful when, for example, you’ve designed a business card in your drawing program and want to duplicate it enough times to fill a letter-sized printout. On the other hand, whenever you next copy or cut something, whatever was previously on the Clipboard is lost forever.

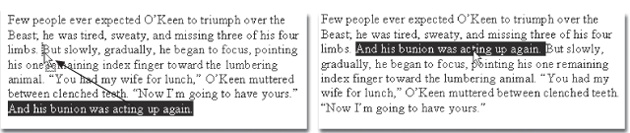

As useful and popular as it is, the Copy/Paste routine doesn’t win any awards for speed; after all, it requires four steps. In many cases, you can replace it with the far more direct (and enjoyable) drag-and-drop method. Figure 10-4 illustrates how it works.

Tip

To drag highlighted material offscreen, drag the cursor until it approaches the top or bottom edge of the window. The document scrolls automatically; as you approach the destination, jerk the mouse away from the edge of the window to stop the scrolling.

Several of the built-in Windows programs work with the drag-and-drop technique, including WordPad and Mail. Most popular commercial programs offer the drag-and-drop feature, too, including email programs and word processors, Microsoft Office programs, and so on.

Note

Scrap files—bits of text or graphics that you can drag to the desktop for reuse later—no longer exist in Windows.

As illustrated in Figure 10-4, drag-and-drop is ideal for transferring material between windows or between programs. It’s especially useful when you’ve already copied something valuable to your Clipboard, since drag-and-drop doesn’t involve (and doesn’t erase) the Clipboard.

Its most popular use, however, is rearranging the text in a single document. In, say, Word or WordPad, you can rearrange entire sections, paragraphs, sentences, or even individual letters, just by dragging them—a terrific editing technique.

When it comes to transferring large chunks of information from one program to another—especially address books, spreadsheet cells, and database records—none of the data-transfer methods described so far in this chapter does the trick. For such purposes, use the Export and Import commands found in the File menu of almost every database, spreadsheet, email, and address-book program.

These Export/Import commands aren’t part of Windows, so the manuals or help screens of the applications in question should be your source for instructions. For now, however, the power and convenience of this feature are worth noting. Because of these commands, your four years’ worth of collected names and addresses in, say, an old address-book program can find its way into a newer program, such as Mozilla Thunderbird, in a matter of minutes.