Ecology, Allegory, and Indigeneity in the Wolf Stories of Roberts, Seton, and Mowat

In his now classic introduction to The Kindred of the Wild, Charles G.D. Roberts characterized the type of animal story that he and Ernest Thompson Seton pioneered at the end of the 19th century as a triumph of realism over allegory in which the anthropomorphism of Aesop’s fables and the anthropocentrism of Rudyard Kipling were at last decisively dispatched. More importantly, however, he also linked this empirical claim to a new understanding of non-human consciousness predicated on the post-Darwinian disintegration of the conventional barrier between human and animal species. In a crucial passage of this preface he defends the reasoning power of animals and argues that

[a]s far… as … mental intelligence is concerned, the gulf dividing the lowest of the human species from the highest of the animals has in these latter days been reduced to a very narrow psychological fissure…. Looking deep into the eyes of certain four-footed kindred, we have been startled to see therein a something, before unrecognised, that answered to our inner and intellectual, if not spiritual selves…. We have come face to face with personality, where before we were blindly wont to predicate mere instinct and automatism…. [Thus,] the animal story at its highest point of development is a psychological romance constructed on a framework of natural science. (23–24)

Numerous critics have warned us to be skeptical of Roberts’s empirical and realist claims, pointing out that there is more “romance” than “natural science” in these fictions. James Polk was among the first to see Roberts’s animal stories as national allegories that revealed a “persecuted” Canadian psyche obsessed with “questioning its own national identity” and “suspici[ous] that a fanged America lurks in the bushes, poised for the kill” (58); Joseph Gold sees Roberts’s stories as “post-Darwinian and post-Freudian” fables in which the depiction of animals “tearing each other to pieces, dripping with blood, [and] driven to frenzy by hunger or oestrus” is not intended “to show us what animals are like, but what we are like” (79–80, 81); conversely, Robert H. MacDonald views the stories of both Seton and Roberts as reinventions of the beast fable tradition that re-instantiate moral allegory in an ethical “revolt against Darwinian determinism” (18); and Misao Dean has similarly warned that “no realism is transparent” (3), arguing that Roberts’s four-footed kindred are really “(m)animals” (5), “models of ideal autonomous selfhood, masculine and free from the taint of civilised life” (4). As Margaret Atwood puts it summarily in the “Animal Victims” chapter of Survival, “‘realism’ in connection with animal stories must always be somewhat of a false claim, for the simple reason that animals do not speak a human language; nor do they write stories” (74–75). But even if Atwood is correct in asserting that “animals in literature are always symbols” (75), Roberts’s preface remains an important touchstone for thinking about the animal story well into the 20th century because its famous declaration of animal-human kinship displays the central strategy of ecological discourse in its paradigmatic form.

Since its beginnings in the short fiction of Seton and Roberts, the Canadian animal story has been an important site for the exploration of ecological themes and the popularization of conservationist ideals. Following Roberts, early- and mid-century naturalists and animal rights advocates like Grey Owl, Farley Mowat, and Fred Bodsworth often made the case for conservation by contesting the notion of a “species boundary” between human beings and animals. For these writers, some degree of anthropomorphism was not a pitfall to be avoided in the quest for greater empirical accuracy in depicting animal consciousness; on the contrary, anthropomorphism or even personification was implicit in their presumption of a fundamental kinship between animal and human subjects. As the terminological difficulty that words like “anthropomorphism” and “personification” advertises, this form of conservationist discourse displays a curious paradox that Roberts’s preface makes visible: namely, at the very moment that the animal story achieves a new level of “realism,” distinguishing it from the anthropomorphism of the past, the traditional criteria by which realist representations of the animal might be judged have become so unstable that anthropomorphism returns through the back door. The formerly “unrealistic” assignation of conventionally human traits like “personality” to animal beings paradoxically becomes the marker of a new, heightened form of mimesis that acknowledges a common ontology by reintroducing “anthropomorphic” traits in more subtle ways. In other words, despite its claim to have banished animal allegory, Roberts’s “natural science” is crucially supplemented by “psychological romance,” and Victorian talking animals like Br’er Rabbit and the Flopsie Bunnies paradoxically anticipate an ecological rhetoric of animal “personality” whose persuasive efficacy depends precisely on its blurring of the already nebulous border between realism and fantasy—a border whose ambiguity marks the epistemological limit of all empirical claims concerning the representation of animal consciousness.

Farley Mowat’s ecological “potboiler” Never Cry Wolf (1963) exemplifies this boundary-crossing strategy (Mowat qtd. in King 198). A bestseller when it was first published, the book details Mowat’s experiences studying the relationship between Arctic wolves and thinning caribou herds in the Keewatin district for the Dominion Wildlife Service in 1948. Cast as a wholesale indictment of Ottawa-sponsored “predator control” programs that—according to Mowat—were instigated primarily by angry hunters and a calculating tourism industry, the book charges the government with “crimes against nature” (vii) and “biocide” (viii), making “a plea for [the] understanding and preservation of an extraordinarily highly evolved and attractive animal which was, and is, being harried into extinction by the murderous enmity and proclivities of man” (v). Because Mowat sees the campaign against wolves as ultimately rooted in a perception of the animal as “a savage [and] powerful killer” (40), Never Cry Wolf presents itself primarily as a work of demystification whose principal aim is to refute stereotypes of the wolf as a satanic beast or a devourer of little red-cloaked girls. To this end, the book begins strategically in the fairy tale setting of “Grandmother Mowat’s house” (1) and traces the author’s gradual immersion into the world of the wolf, dramatizing his discovery that “the centuries-old and universally accepted human concept of wolf character was a palpable lie” (51). This dramatization proceeds through a series of self-mocking episodes in which Mowat performs the role of nervous, wolf-fearing urbanite. In one scene he cowers under a canoe in the barrens, hiding from a pack of amiable Huskies that he has mistaken for ferocious wolves (27–29); in another, he flees from a surprise encounter with a real wolf who is evidently more frightened of Mowat than Mowat is of him (36–37). These scenes of comic self-abasement are supplemented by an ecologically-centred account of the wolf-caribou relationship as one of symbiosis rather than wanton predation, and a related thesis that Arctic wolves’ primary form of subsistence is not caribou but mice. From a rhetorical point of view, however, the most important strategy the book employs is to attack the species barrier upon which the popular vilification of the wolf is premised.

As Marta Dvorak has shown, the affective power of Never Cry Wolf depends primarily on the folksy presentation of its subjects as the lupine equivalents of “the ideal human family of western 19th to mid-20th century patriarchal middle-class society” (233). “George,” his “wife,” “Angeline,” their pups, and “Good Old Uncle Albert” (who “baby sits” the pups when mom and dad want a night out), are imbued, in Mowat’s anthropomorphic account, with a full range of humanizing traits. George is “the kind of father every son longs to acknowledge as his own” (61). Angeline is “the picture of a minx. Beautiful, ebullient, passionate to a degree and devilish when the mood was on her” yet also—predictably—“the epitome of motherhood” to whom Mowat acknowledges a coy Oedipal attraction. “I became deeply fond of Angeline,” he confesses, “and still live in hopes that I can somewhere find a human female who embodies all her virtues” (62). Indeed, the dedication to Never Cry Wolf reads: “for Angeline—the Angel!” and elsewhere Mowat slyly notes that “wolves are not against miscegenation” (102).

As Mowat’s mock-flirtation with his lupine muse suggests, the challenge to species boundaries in Never Cry Wolf cuts two ways as the text experiments with both humanizing the wolves and animalizing the author, who increasingly enters into what postidentitarian philosophers Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari might call a becoming-wolf. “I went completely to the wolves” (53), Mowat declares after he has “discarded] the accepted concepts of wolf nature” (51–52)—a process which leads not only to ‘setting up a den of [his] own” (53), but to learning how to fish like a wolf (83), taking “wolf naps” (60), eating mice (he provides a recipe for something called Souris à la Crême) (77), and—most infamously—marking his territory in true lupine fashion with the help of several pots of tea and a healthy bladder. Such instances of boundary-crossing culminate in a chapter tellingly entitled “Naked to the Wolves” in which Mowat anticipates and outdoes Kevin Costner’s Dances with Wolves (1990) by joining a wolf pack’s playful harrying of a caribou herd wearing nothing but his rubber boots.

As important as the strategic blurring of the species boundary might be for conservationist writing, Mowat’s fascination with going wolf in these examples suggests that there is more at stake in this “literary howl” (Jones 135) than wolf conservation. As I will argue, Mowat’s rhetoric of transgression is double-voiced, if not Janus-faced: the erosion of the species boundary in his representation of wolves can in one sense be read as a conservationist strategy, but the text’s ecological rhetoric simultaneously allegorizes an implicitly nationalist discourse of prim-itivist fantasy. My main concern in this essay is to specify the nature and function of this interlacing of ecology and primitivism by examining how the rhetoric of boundary-crossing in Never Cry Wolf overlaps with and reinforces cultural metanar-ratives of romantic nationalism and indigenization, creating a veiled “postcolonial” allegory that mitigates settler-invader guilt by legitimizing the displacement and dispossession of First Nations people. Without denying that Never Cry Wolf is explicitly concerned with popularizing wolf ecology and preservation and has been successful on that basis, I argue that the phenomenal popularity of this national bestseller by “Canada’s Greatest Storyteller” (cover text) cannot easily be separated from its uncanny ability to evoke the indigenizing fantasies of settler-invader postcolonialism in a displaced but still potent form. Indeed, Mowat’s identification with wolves is symptomatic of his investment in such metanarratives, for the wolf-indigene homology is ubiquitous in Canadian literature and informs even the ostensibly referential animal stories of the genres earliest practitioners. In order to demonstrate the pervasiveness of this tradition, I begin by tracing the parallels between nationalist discourses of indigenization and conservationist discourses of animal-human “kinship,” both of which foreground tropes of identification and extinction that are paradigmatically expressed in the form of prolep-tic elegy. I then examine the conceptual compatibility between wolf and indigene and suggest how this compatibility informs the animal stories of Roberts and Seton. Finally, I return to Mowat’s Never Cry Wolf to show how it may be read as an elaboration of Roberts’s and Seton’s lupine fables of indigenization and to examine ways in which the trope of crossing the species boundary that pervades ecological rhetoric remains inextricably bound up in racialized fantasies of becoming native. Like Gordon Sayre—who has traced parallels between early ethnographies of Native American society and “beaver-ethnograph[ies]” such as Horace T. Martin’s Castorologia and shown how “the idealized portrayal of the beaver” in colonial travel writing “resembles that of the Noble Savage in its ideological function” (660, 665)—I argue that it is necessary to situate representations of popular animal species within a postcolonial framework of analysis that remains critical of settler-invader nationalism.

As Alan Lawson argues in his seminal articulation of the “settler subject,” the metanarrative of settler-invader postcolonialism has “a double teleology: the suppression or effacement of the indigene, and the concomitant indigenization of the settler, who, in becoming more like the indigene whom he mimics, becomes less like the atavistic inhabitant of the cultural homeland whom he is also reduced to mimicking” (28). In other words, within this cultural metanarrative, indigenization—the “effacement (of Indigenous authority) and [the] appropriation (of Indigenous authenticity)” (26)—is an implicitly imperialist, nation-building form of symbolic management through which the settler-invader’s dilemma of anxious unbelonging is imaginatively, if temporarily, resolved. Within this symbolic economy, “the vanishing Indian” and “the dying race” are the central tropes by which the process of indigenous effacement and appropriation is figured and sanctified. Indigenization narratives are thus paradigmatically marked by what Patrick Brantlinger calls the “performative” discourse of proleptic elegy—a form of extinction discourse whose “future-perfect mode … mourns the lost object before it is completely lost” (4),

sentimentally or mournfully expressing, even in its most humane versions, the confidence of a self-fulfilling prophecy, according to which new, white colonies and nations arise as savagery and wilderness recede. Proleptic elegy is thus simultaneously funereal and epic’s corollary—like epic, a nation-founding genre. (3)

As Brantlinger points out, moreover, the discourses organizing myth of the vanishing Indian was significantly strengthened by the slippage between “species” and “race” in Victorian theories of evolution. Darwin, Spenser, and Huxley all translated the biological notion of “the survival of the fittest” into a competition between “higher” and “lower” races in which “civilization” becomes “virtually identical to imperialism, because both entail the conquest and domestication of savages” (Brantlinger 176).

The nationalist-imperialist form of extinction discourse Brantlinger describes resonates powerfully with the proleptic elegies of conservation discourse, despite the fact that the representation of animal victims and the projected extinction of animal species in animal stories like Never Cry Wolf or The Last of the Curlews is intended as neither an evolutionary inevitability nor a “self-fulfilling prophecy,” but as a dire warning and an impetus to humanitarian intervention. Seton, for instance, concludes his Note to the Reader that begins Wild Animals I Have Known with a plea for animal rights on the grounds that “we and the beasts are kin. Man has nothing that the animals have not at least a vestige of, the animals have nothing that man does not to some degree share” (15). Yet, when read in their national-postcolonial context, the representations of animal victims in these stories may in some cases evoke the indigenizing proleptic allegories of “doomed races,” or even, as Terry Goldie has noted, “dead races” where the form is no longer even proleptic but simply “[t]he ethnography of an extinct people” (155).

This haunting of the Canadian animal story by the ghosts of dying Indians is due in part to the common grounding of indigenization and conservation discourses in a poetics of extinction and transgression. But it also reflects the more fundamental fact that the border-crossings between races (indigenization) and between species (conservation) that they figure both exploit the same evolutionary premise, positing differences of degree rather than differences in kind and thus making transgression imaginable. Moreover, as an evolutionary concept that mediates between similarity and difference not only within race and species discourses but also between the very concepts of human race and animal species, “kinship” had immediate and profound implications for the categorization of “human” and “animal” groups alike, for the relations between them, and for the cultural uses to which such relations could be put. Kinship, in short, provided a conceptual basis for identifying “lower races” with “higher animal species.” As Thomas R. Dunlap argues:

[B]lurring the boundaries between man and the animals, [Darwinian biology] encouraged racial classifications based on purported distance from the beasts and theories about the survival of primitive features among civilized men. Scientists, including the new animal psychologists found considerable overlap between the lower races of man and animals…. From this it was only a short step to the theory of recapitulation, most often associated with G. Stanley Hall, a psychologist whose work “suggested that children would wholly mature only if they were encouraged to relive the history of the human race.” Seton was struck with this idea and incorporated its implications into the program of the Woodcraft Indians. (109)

Such a slippage between categories of “species,” “race,” and “culture” (particularly as these terms move from disciplinary to popular articulation) has certainly been one of the most persistent features of Victorian anthropological discourse to survive the transition to the 20th century (Stocking 324–329), and as Dunlap’s example of the Woodcraft Indians suggests, this slippage is constitutively embedded within indigenizing discourse itself. Separating race from species in the realm of popular (and especially settler-nationalist) representations of animals thus cannot be accomplished simply by swearing a Robertsonian oath of allegiance to “natural science,” particularly when the purpose of such an oath is to undercut the species boundary by complicating scientific naturalism with anthropomorphic elements of “psychological romance.”

In the animal stories of Roberts and Seton, the categorical and structural parallels between conservation and indigenization narratives—between “animals” and “Indians”—converge with particular intensity around the figure of the wolf, an animal that, like the indigene himself, has alternately been pictured as a demonic and an idealized embodiment of nature or “wildness.” Indeed, in the 19th and 20th centuries, the trajectory of the wolf’s popular reputation has often followed that of savagery, moving from largely negative to largely romanticized representations. Seton’s insistence in the preface to Mainly About Wolves (1937) that wolves aren’t simply destructive predators but have “personalities … as diverse as saint and devil” (ix) locates his work precisely on the cusp of this transition.

The profound discursive overlap—even near identity—between wolf and indigene in primitivist discourse throughout the 20th century is perhaps most emblematically suggested by nature writer Barry Lopez’s Of Wolves and Men (1978). In this Chatwinesque meditation on lupine behaviour, Lopez acknowledges that the wolf is “not so much an animal that we have always known as one that we have consistently imagined” (204). Yet his text is still prone to reproducing primitivist gestures of identification between wolf and indigene, framing its sympathetic portrait of the wolf with a speculative form of ethology that would infer the meaning of wolf behaviour in the Arctic by observing the practices of contemporary but ostensibly “timeless” Native and Inuit societies (78) and tracing correspondences between “wolf and primitive hunter” (88). Lopez is an ambivalent primitivist rather than a naïve one, for he encourages his reader to be “both open-minded and critical” of the wolf-indigene homology he develops, insisting:

I will not try to prove that primitive hunting societies were originally or psychologically organized like wolves that lived in the same environment, though this may be close to the truth. What I am saying is this: we do not know very much at all about animals…. It behooves us to visit with a people with whom we share a planet and an interest in wolves but who themselves come from a different time-space and who, so far as we know, are very much closer to the wolf than we will ever be. (86; emphasis added)

Despite minor qualifications, this is a primitivism that is considerably more “open-minded” than “critical,” for within Lopez’s romantic narrative, indigenous groups remain “timeless” purveyors of “ancient ideas” even if “they happen to live in our own age” (78). When Lopez speculates that “[t]he Eskimo … probably sees in a way that is more analogous to the way the wolf sees than Western man’s way of seeing is” and expresses excitement that even though we cannot communicate directly with wolves “we can converse with Eskimos” (87), “the Eskimo” becomes not just a noble savage but a kind of speaking wolf. In this way, Lopez implicitly re-inscribes an evolutionary discourse of kinship between “the lower races of man and animals” (Dunlap 109) in order to imagine a “native informant” with privileged access to an otherwise untranslatable animal consciousness.

Anticipations of this kind of primitivist homology between wolf and indigene are already visible in the wolf stories of Roberts, though usually in less romantic, more ambivalent forms. As Alec Lucas observes, Roberts’s predilection for celebrating superior or exceptional animals—“‘kings’ of the[ir] species”—transforms many of his animal heroes into “noble savages” who, like “epic heroes,” embody the primordial virtues of courage, freedom, and indomitability (385). But there is nothing “noble” about Roberts’s fictional wolves, which are almost always portrayed as irredeemably “savage” predators. Indeed, Roberts’s wolf stories characteristically dramatize Darwinian competitions for survival and celebrate trapper or hunter “woodsman” figures in narrative structures that suggest fables of indigenization by penetration—a form of indigenization discourse that demonizes the indigene as the embodiment of a hostile wilderness whose “natural” barbarism justifies imperial violence in advance (Goldie 15). Typically, the plot centres on a hunter who finds himself in direct competition with a wolf pack and ultimately demonstrates his evolutionary superiority by subduing the pack in a bloody forest massacre that allows him to claim the spoils of their contest for himself.

In “Wolf! Wolf!” for instance, expert backwoodsman Sim Purdie is stalked through the bush by a ravenous wolf pack after he robs them of the doe they have been hunting. Pursued by “savage snarls” (177) and the “ghostly rustling of padded feet” (181), Purdie flees with his prize toward “home and safety” (183)—a suggestive narrative trajectory whose juxtaposition of a “savage” and “ghostly” indigenous animal species with the promise of home and security for the woodsman seems to register, in displaced fashion, the very settler-invader anxieties about belonging that indigenization narratives serve ultimately to allay through the construction of legitimizing allegories. In this case, the allegory is structured largely by a Darwinian rhetoric of penetration that legitimizes Purdies theft of the wolves’ resources, his eventual slaughter of the wolf pack, and his claim to their forest home by constructing the wolves as cannibals and by constructing Purdie himself as an evolutionarily superior species. The narrative is significantly focalized through Purdie’s perspective, rather than through that of the wolves, and at a climactic moment in the story, Purdie defends himself against “a big wolf, bolder than his fellows,” striking him down with his axe. He flees to the sound of “a turmoil of harsh snarls as the wolves threw themselves upon the body of their slain comrade and ravenously tore it to pieces” (181). This “cannibalistic repast” (182) is of particular symbolic importance to the story’s ability to function simultaneously as wilderness adventure and indigenization narrative, for Roberts’s use of a term from colonial discourse that is usually reserved for characterizing indigenous “savagery” lends the woodsman’s triumph over the wolves an additional resonance. Moreover, the implicit identification of the “cannibalistic” wolves with stereotypes of savage indigeneity is emphasized by the narrator’s ironically anthropomorphizing observation that “[a]ssuredly, those wolves had never been taught the hygienic importance of eating slowly and chewing their food thoroughly” (185)—unlike civilized Purdie who carefully dissects the carcass of the doe, collects a “quantity of bones for soup,… [gets] the fire going in his handy little stove, and then, in huge content, proceed[s] to cook himself such a meal as his whole being had been hankering after for many weeks” (185–186). Such contrasts between the raw and the cooked, between cannibalism and legitimate consumption, reinforce the story’s allegorical meaning as an indigenizing narrative by structuring the battle between wolf and woodsman through the cultural categories of colonial discourse. Predictably, the battle between savagery and civility ends in Darwinian triumph for the settler: “set[ting] the gun to his shoulder, and with a grim smile, [Purdie] began picking off his antagonists carefully, one by one,” eventually “dragging] the dead wolves indoors to be skinned, for their fine pelts, at his leisure” (184–185). Many of Roberts’s other wolf stories—“With His Back to the Wall,” “Wild Motherhood,” and “The Invaders”—are all variations on this basic Darwinian grammar.

Despite the rhetoric of fear that informs the identification of wolf and indigene in these stories, they also contain an implicit suggestion of indigenization by appropriation—a form of indigenization narrative that inverts the logic of penetration, idealizing the indigene as a spiritual embodiment of the landscape and replacing evolutionary agon with a desire for integration, initiation, and absorption (Goldie 15). For instance, many of these stories conclude not simply with the woodsman’s triumph over the wolves but with his consumption of their flesh and, as in “Wolf! Wolf!” his appropriation of their pelts. More subtly, these human-wolf competitions often end with a reversal that stresses the human hero’s special kinship with the world of nature. This process, in which the prized object of competition is unexpectedly released because the hunter is moved by a sudden feeling of sympathy with the hunted, displaces his veiled identification with indi-geneity onto a less threatening intermediary. Such is the case in “With His Back to the Wall,” a story in which a wounded trapper and an old black bear make a successful stand against an encroaching wolf pack and the trapper cannot bring himself to shoot the bear, even though he acknowledges that “bear meat’s a sight better eatin’ than wolf.” Lowering his gun, the trapper addresses the bear directly over the carcasses of the wolves: “No, old pardner,… that would be a low-down trick to play on ye, seein’ as how we’ve fought shoulder to shoulder, so to speak. An’ a right slick fight ye’ve put up! Here’s my best wishes, an’ may ye keep clear of my traps!” (209–210). With this cordial send-off, the woodsman demonstrates that his evolutionary advantage is predicated on a kind of primitivism that Roberts is anxious to distinguish from the utter savagery of the wolf pack. In this way the limited extent to which the woodsman goes native is consistent with Roberts’s mandate that the animal story “return [us] to nature, without requiring that we at the same time return to barbarism” (29). Thus Roberts can celebrate the woodsman as “a better hunting animal than the best of them” who can “hear as well as a listening moose” and “see as far as the lynx, and with a more discriminating vision” (194–195), despite the story’s demonization of indigene in the form of the wolf pack. In other words, the trapper’s identification with non-lupine animals like his “old pardner” the black bear provides Roberts with a way of managing the tensions that emerge between evolutionary narratives of penetration and primi-tivist fantasies of appropriation in the stories’ indigenizing allegory, allowing him to have his wolves and eat them too.

If Roberts’s wolves generally represent a threatening indigeneity whose savagery legitimizes indigenizing narratives of penetration and licenses a partial, tightly controlled version of going native, Seton’s wolves are of a decisively different breed. The difference between Roberts’s and Seton’s wolf stories resides in the fact that the latter are deeply informed by a more romantic primitivist revolt against civilization that stamped much of Seton’s career, particularly his development of the Woodcraft Indians, a precursor to the Boy Scouts whose motto was “The best things of the best Indians” (“Woodcraft” 353) and whose activities centred on picturesque simulations of tribal life. Seton’s promotion of a Fenimore Cooper version of native culture as an alternative to Western values inverts Roberts’s recoil from “barbarism” and constitutes a striking example of indigenization by appropriation, complete with the requisite proleptic elegy that mourns the departure of “the noble red man … before [his] day” (“Woodcraft” 349).

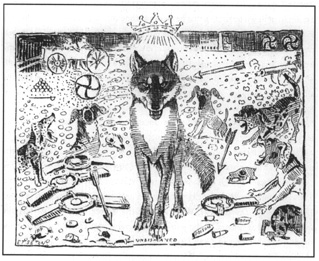

Seton’s stories of noble but persecuted wolf-heroes blessed with “superlupine” traits are allegorical variants of this dying Indian motif. Stories like “Lobo, the King of Currumpaw,” “Wosca and her Valiant Cub,” and “The Winnipeg Wolf,” for instance, chronicle the extermination of exceptional wolves whose capacity for love, loyalty, and daring subverts the stereotype of the “destructive predator” and echoes Seton’s idealization of Native culture as a vanishing source of value. Whereas Roberts presents wolf-extermination narratives as Darwinian triumphs, Seton presents them as tragedies or martyrdoms. His drawing of a Christlike crowned “Wosca” (Figure 1) who is “undismayed” by the encroaching threat of dogs, bullets, traps, and poison is emblematic of this attitude.

FIGURE 1 Wosca

Seton’s rejection of the overtly imperialist rhetoric of penetration in the wolf stories is accompanied by the introduction of rhetorics of desire and appropriation. In “The Wolf and the Primal Law,” for example, a foreigner named Yan possesses an Orphic sympathy with the animals that verges on “telepathy” and hints at a past life as a wolf. Travelling through Canada and “communing” with wolves, Yan is a quintessential example of indigenization through appropriation— a point underlined by the fact that he shares a name with the protagonist of Seton’s Two Little Savages, an autobiographical account of the author’s initiation into woodcraft. Yan the wolf-man, in other words, is a thinly-veiled version of Seton the woodcraft Indian who famously signed his own work with the paw-print of a wolf.

Half a century later, Mowat’s wolf stories rehearse and develop these lupine allegories of indigenization in ways that are both more explicit than those of Roberts and, as we will see, more anxious than those of Seton. Mowat had read Seton as a boy and even “decided to become an Indian himself” after reading Two Little Savages (King 28). Like Seton, moreover, Mowat acquired an interest in wolves that reflected an even deeper fascination with indigenous people. By the time Mowat began writing Never Cry Wolf in 1960, he had just completed The Desperate People (1959), a quasi-ethnography about a dying group of inland Eskimos named the Ihalmiut that was a sequel to Mowat’s first book on this topic, The People of the Deer (1952). Moreover, like the wolves of Never Cry Wolf, the Ihalmiut were residents of the sub-Arctic Barrens, and Ootek (an important supporting character in Never Cry Wolf) is clearly identified as a member of Mowat’s “Desperate People.” Within this context, Mowat’s proleptic elegy for Arctic wolves takes on a depth of symbolic resonance that invites an allegorical reading through its repeated identification of the wolf with an untarnished and desired indigeneity.

This identification is typically figured in Mowat’s book through the motif of kinship between wolves and Eskimos, and more particularly through Mowat’s relationship with the young Ihalmiut man named Ootek, whom Mowat characterizes as “a minor Shaman” (80) and “spiritually almost a wolf himself” (100). Often accompanying Mowat on his wolf-watching, Ootek not only confirms the author’s ecological thesis about the symbiotic relationship between wolves and caribou (84–85), but also serves as the primary interface between wolves and indigeneity in the text: “[Ootek] too,” Mowat learns,

was keenly interested in wolves, partly because his personal totem, or helping spirit, was Amarok, the Wolf Being…. In fact, he was so close to the beasts that he considered them his actual relations. Later, when I had learned some of his language and he had improved in his knowledge of mine, he told me that as a child of about five years he had been taken to a wolf den by his father, a shaman of repute, and had been left there for twenty-four hours, during which time he made friends with and played on terms of equality with the wolf pups, and was sniffed at but otherwise unmolested by the adult wolves. (80–81)

This account of Ootek’s childhood trip to the wolf den anticipates Mowat’s attempt to recreate this experience for himself in the concluding chapter of the book, and as we learn later, Ootek even conducted his own independent wolf studies as a young man. As such details suggest, Ootek functions as Mowat’s double in Never Cry Wolf, simultaneously anticipating, legitimizing, and interpreting Mowat’s own “going to the wolves” as a form of going native. Ootek’s conviction that Mowat “must be a shaman too” (80) is only the most blatant example of the slippage between lupine realism and indigenizing allegory in Mowat’s desire to “go wolf.”

If Mowat’s conservatiohism and its challenge to species boundaries overlaps in suggestive ways with a settler narrative of indigenization and the challenge to racial and cultural boundaries that this narrative entails, as I have argued, what makes Mowat’s articulation of this overlap curious is his insistence that he has failed to become anything more than a “pseudo-wolf” (146)—and by implication, a pseudo-indigene. This failure is the subject of the concluding scene of the book when Mowat descends into a wolf den that he believes to be empty but in fact contains Angeline and one of her pups, “scrunched hard against the back wall of the den … as motionless as death” (162). Instantly reverting to his previous fear of wolves in the confined space of the den, Mowat flees and is left reflecting on the collapse of his hopes for interspecies harmony:

I was appalled at the realization of how easily I had forgotten, and how readily I had denied, all that the summer sojourn with the wolves had taught me about them … and about myself. I thought of Angeline and her pup cowering in the bottom of the den where they had taken refuge from the thundering apparition of the aircraft, and I was shamed.

Somewhere to the eastward a wolf howled; lightly, questioningly. I knew the voice, for I had heard it many times before. It was George, sounding the wasteland for an echo from the missing members of his family. But for me it was the voice which spoke of the lost world which once was ours before we chose the alien role; a world which I had glimpsed and almost entered … only to be excluded, at the end, by my own self. (162–163)

In the context of the conservationist narrative, Mowat’s concluding reassertion of the species boundary is an important rhetorical move. It returns the reader to an unpleasant reality and reveals the pastoral space of wolf-human boundary crossing in Wolf Bay as a virtual or Utopian possibility from which we will all be excluded unless the wolf hunt is ended. In this regard, it provides a powerful concluding spur to the reader that is reinforced by the book’s epilogue, where we are told that “during the winter of 1958–59, the Canadian Wildlife Service, in pursuance of its continuing policy of wolf control” returned to Wolf Bay and set a trap to kill the remaining wolves, the results of which Mowat does not disclose (164).

When read in allegorical terms, however, the conclusion of the book assumes a very different significance. On one hand, the ending’s strongly implied proleptic elegy fulfills the settler fantasy of indigenization by symbolically eliminating those presences that would contest his claim to authenticity. At the same time, however, other details of the ending, such as Mowat’s unsettling discovery that the wolf den he sought to colonize was actually still inhabited, his reassertion of the species boundary through the rhetoric of self-exclusion, and his related despair that he can only ever be a “pseudo-wolf,” all suggest that Mowat’s indigenizing narrative is actually blocked by a persistent, and as Mowat notes elsewhere, increasingly vocal, aboriginal presence.

Much of the angst that accompanies Mowat’s underlying anxiety that the species barrier and its cultural equivalent cannot ultimately be transgressed can be traced to Mowat’s awareness that the indigenizing fantasy itself cannot be sustained in its conventional form in the face of increasingly audible Native demands for political justice and cultural recognition, demands that remind him that Aboriginal people are not vanishing, but are in fact his political contemporaries. As I have argued elsewhere, Mowat himself records this challenge to the indigenizing narrative in the bracing final chapter of The Desperate People in which he ventriloquizes such demands for Native self-determination (Johnson). But he also registers elements of this challenge in Never Cry Wolf. When Mowat asks hopefully “if [Ootek] had ever heard of the time-honoured belief that wolves sometimes adopt human children” he records his disappointment at Ootek’s “rather condescending refusal to accept the wolfboy as a reality”: “a human baby put in a wolf den,” Ootek explains to Mowat, “would die, not because the wolves wished it to die, but simply because it would be incapable, by virtue of its inherent helplessness, of living as a wolf” (100). I would thus ultimately read Never Cry Wolf as Mowat’s ambiguous and conflicted consolation for Ootek’s refusal to indulge the settler-invader fantasy of cross-cultural adoption and transformation. It is ambiguous because while Mowat is intellectually honest enough to record indigenous refusals of this fantasy, he remains committed to its representation through the symbolic substitution of wolf for indigene.

In a crucial passage near the end of the book, Mowat attempts a revealing act of symbolic reorganization that would separate wolf from indigene just enough to reopen the possibility of indigenization that Ootek’s refusal appears to have closed off. “This country,” he writes,

belonged to the deer, the wolves, the birds, and the smaller beasts. [Ootek and I] were no more than casual and insignificant intruders. Man had never dominated the barrens. Even the Eskimos, whose territory it had once been, had lived in harmony with it. Now these inland Eskimos had all but vanished. The little group of forty souls to which Ootek belonged was last of the inland people, and they were all but swallowed up in this immensity of wilderness. (126)

As they do in this example, the wolves of Never Cry Wolf seem ultimately to trump the indigeneity of the Eskimo to become ciphers for an indigeneity that is now truly a fantasy—an indigeneity that cannot answer back and contest the desires of settler-invader nationalism. Ultimately, then, Never Cry Wolf demonstrates the way in which the violation of species boundaries in conservationist discourse can unwittingly provide a detour for nationalist yearnings for indigenization that are blocked in their more conventional form. This is not to suggest that the challenge to species boundaries in Never Cry Wolf is only, or exclusively, symbolic. It is to suggest, however, that the profound and problematic overlap between species difference and cultural difference in the imaginative geography of settler-invader literature makes it imperative that we remain conscious of conservationist discourse’s multiple ideological entailments and of its potential for slipping from non-symbolic representations of animal victims to elegiac allego-rizations of national species.

Atwood, Margaret. Survival:A Thematic Guide to Canadian Literature. Toronto: Anansi, 1972.

Bodsworth, Fred. Last of the Curlews. Toronto: McClelland & Stewart, 1991.

Brantlinger, Patrick. Dark Vanishings: Discourse on the Extinction of Primitive Races, 1800–1930. New York: Cornell, 2003.

Dean, Misao. “Political Science: Realism in Roberts’s Animal Stories.” Studies in Canadian Literature 21.1 (1996): 1–16.

Dunlap, Thomas R. “‘The Old Kinship of Earth’: Science, Man and Nature in the Animal Stories of Charles G.D. Roberts.” Journal of Canadian Studies 22.1 (1987): 104–120.

Dvorak, Marta. “Of Mice and Wolves and Farley Mowat.” La création biographique/Biographical Creation. Rennes: PU de Rennes, 1997.227–236.

Gold, Joseph. “The Ambivalent Beast.” The Proceedings of the Sir Charles G.D. Roberts Symposium. Ed. Carrie Macmillan. Halifax: Nimbus, 1984.77–86.

Goldie, Terry. Fear and Temptation: The Image of the Indigene in Canadian, Australian, and New Zealand Literatures. Montreal & Kingston: McGill-Queen’s UP, 1989.

Johnson, Brian. “Viking Graves Revisited: Pre-Colonial Primitivism in Farley Mowat’s Northern Gothic.” Australasian Canadian Studies 24.2 (2007): 59–92.

Jones, Karen R. Wolf Mountains: A History of Wolves Along the Great Divide. Calgary: U of Calgary P, 2002.

King, James. Farley: The Life of Farley Mowat. Toronto: HarperCollins, 2002.

Lawson, Alan. “Postcolonial Theory and the ‘Settler’ Subject.” Essays on Canadian Writing 56 (1995): 20–36.

Lopez, Barry Holstun. Of Wolves and Men. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1978.

Lucas, Alec. “Nature Writers and the Animal Story.” Literary History of Canada. Ed. Carl F. Klinck. Toronto: U of Toronto P, 1973.364–388.

MacDonald, Robert H. “The Revolt Against Instinct: The Animal Stories of Seton and Roberts.” Canadian Literature 84 (1980): 18–29.

Martin, Horace T. Castorologia, or the History and Traditions of the Canadian Beaver. Montreal: Wm. Drysdale & Co., 1892.

Mowat, Farley. The Desperate People. Toronto: Seal, 1980.

______. Never Cry Wolf. Toronto: Seal, 1985.

______. The People of the Deer. New York: Pyramid, 1952.

Polk, James. “Lives of the Hunted.” Canadian Literature 53 (1972): 51–59.

Roberts, Charles G.D. “The Invaders.” The Feet of the Furtive. London, Melbourne, and Toronto: Ward, Lock, & Co., n.d. 91–116.

______. The Kindred of the Wild: A Book of Animal Life. Boston: L. C. Page & Co., 1922.

______. “Wild Motherhood.” Tales of the Canadian North. Ed. Frank Oppel. Secaucus: Castle, 1984.155–160.

______. “With His Back to the Wall.” The Feet of the Furtive. London, Melbourne, and Toronto: Ward, Lock, & Co., n.d. 187–211.

______. “Wolf! Wolf!” Eyes of the Wilderness. Toronto: MacMillan, 1933.176–186.

Sayre, Gordon. “The Beaver as Native and as Colonist.” Canadian Review of Comparative Literature/Revue canadienne de littérature comparée September/December (1995): 659–682.

Seton, Ernest Thompson. “Lobo, the King of Currumpaw.” Wild Animals I Have Known. 19–44.

______. Mainly About Wolves. London: Methuen, 1937.

______. “The Rise of the Woodcraft Indians.” Ernest Thompson Seton’s America: Selections from the Writings of the Artist-Naturalist. Ed. Farida A. Wiley. New York: The Devin-Adair Company, 1962. 344–354.

______. Two Little Savages, Being the Adventures of Two Boys Who Lived as Indians and What They Learned. New York: Grosset & Dunlap, 1911.

______. Wild Animals I Have Known. Toronto: McClelland & Stewart, 1991.

______. “The Winnipeg Wolf.” Animal Heroes. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1905. 289–320.

______. “The Wolf and the Primal Law.” Mainly About Wolves.

______. “Wosca and her Valiant Cub.” Mainly About Wolves.

Stocking, George W. Victorian Anthropology. Toronto: The Free Press, 1987.