Consultants regularly present the consulting profession as highly intellectual and just a little bit special. Yet underneath the hype, management consulting is merely an industry providing a service in response to a customer’s need. All the normal lessons from sales and marketing apply. The customer may be called the client, but it is only on this client’s willingness to provide money in exchange for the consultant’s service that the industry is built. Selling consulting is not especially difficult, but it is essential for anyone who wants to succeed as a consultant. If you never make a sale then even the best consulting skills in the world are only of theoretical value.

In this chapter I explore the basis for selling consultancy – a client who buys. Later in this book we will discuss interesting and powerful ideas about consulting, but I want to start relatively simply and prosaically, as success as a consultant must start with your feet firmly on the ground! Although the chapter is aimed at external consultants, the lessons are applicable to internal consultants. Whilst the challenge of ‘selling’ services internally within an organisation is different in some respects, for instance the lack of a formal contract, the essential need to identify opportunities and encourage a client to ‘buy’ is still there.

No matter how wonderful, unique or valuable your skills are, no one buys consultancy simply because of your abilities. Clients buy consultancy because they have a need or desire which consultancy is perceived to be capable of fulfilling. This chapter explores what these needs are. One of the fundamental mistakes new consultants make is to misunderstand that it is not skills that create the opportunity for consulting services, but client needs. Skills are required to market and deliver consulting, but if you do not understand your client needs, then you will struggle to sell an engagement. Before you spend time perfecting skills, gaining qualifications or acquiring accreditation you should heed the most basic marketing lesson: to understand what your customers desire.

Having a need is an essential part of a client buying consultancy, but there are additional prerequisites which determine whether a client can and will buy the service you offer, even if it fulfils their needs perfectly. Before considering what makes a client buy, it is useful to look at the prerequisites for purchase. I explain these in the first two sections of this chapter.

Much of this chapter considers the client as if there is an obvious individual client. The final section of this chapter looks at one of the possible minefields of consultancy, in answering an often surprisingly complex question: who is your client?

What are the prerequisite conditions which must be met for it to be possible to sell consultancy? I have identified eight basic prerequisites which must be present in order to sell a consulting engagement:

Without over analysing these prerequisites let’s quickly review them.

The first prerequisite is the most obvious, so obvious it can seem like it need not be stated. Hidden in the obviousness is an unchallenged assumption. The assumption is: if I have business knowledge and skills I can be a successful consultant. Documenting prerequisite 1 may appear unnecessary, but I know of consultants with all sorts of esoteric and interesting skills, for which there is no client. So, unsurprisingly, they do not find work. They moan and ponder about how to increase their skills further, thinking ‘surely then I will gain work’, without noticing that there are many more poorly qualified, but highly successful consultants. Before you spend time analysing and perfecting your service line, check that there is likely to be some form of client. Whatever skills or service line you have – no client, no income!

When there is a potential client, to sell a service, they must have a currently unfulfilled need, and a belief that this need can be fulfilled by consulting. Unfulfilled needs exist aplenty in business. Ask most managers if there is anything they would like help with or problems to be rid of, and you will soon get a very long list. This list radically shortens when you ask them which of these problems is a candidate for resolution by a consultant.

Let us suppose we have met the first three prerequisites. There is a client with an unfulfilled need that they accept they need help fulfilling. We are getting closer to the possibility of selling an engagement. Prerequisites 4 and 5 relate to you personally. The client must know about you. A client cannot buy goods and services they know nothing about. This is a common problem in consulting. If you happen to be working for a major international consultancy most potential clients will have heard of you – although even then, they may well not know your full range of services. On the other hand, if you are a small consultancy or an independent consultant most of your potential clients have no knowledge of your existence. Clients not only need to know about you, but to even get a sniff of real work you need to be perceived as potentially capable of fulfilling their needs. Simply put: are you a known and credible supplier? Unlike the first three prerequisites, prerequisites 4 and 5 are largely in your control and depend on your marketing and networking skills. If you are in a situation in which the answer to this question is no, the follow up is obvious: what will you do to become a known and credible supplier? (See chapters 3, 5 and 9.)

Of course, to perform an engagement you, or someone else you can put forward who meets prerequisites 1 to 5, need to be available to do the work. Consultants use the term availability to refer to time when they are available to work on a live engagement – i.e. time when the consultant is not working on another engagement, busy with business development, sick or on holiday, etc. Availability is difficult to predict. Engagements don’t just end on a fixed date, and the time it takes to sell a consulting engagement does not usually neatly align with the time it takes to complete whatever else you are working on. Get your timing wrong and you may win some work when you are still busy with another client. You do not actually need to be available to perform the engagement to sell the engagement to a client. It is possible to sell work without being available to deliver it, but unless you can make yourself available quickly, the sales activity is a waste of your and your client’s time.

Prerequisites 7 and 8 relate to money. You are a commercial business, and therefore are only going to work if there is access to finance to pay your fees. There are obvious situations in which this is not going to be true; for instance, companies going bankrupt or organisations with very restricted budgets. Commercially, these are to be avoided. As an exception, you may choose to take on some pro bono work for a good cause. I say as an exception not because I want to put you off undertaking pro bono work, but for the simple reason that unless you are privately wealthy it can only be a small proportion of your work or you will not stay in business long. A more common problem is not that an organisation has no money to pay your fees, but that the individual manager who is your potential client has no direct access to a budget or no ability to influence someone else to spend. It is always useful to ascertain early in your client negotiations if a client has sufficient money which they are authorised to spend.

In this section I have summarised the core prerequisites for a client to buy consultancy. Without these prerequisites being in place, no matter how hard you try, there will be no sale. But there is another side to the equation. Not the client perspective, but yours. Although it is not a prerequisite for buying, it should be a prerequisite for selling – that the client can provide you with whatever you need to do your work. Few consulting engagements can be undertaken without any client support. For instance, you may need access to human resources, almost always require some data and information, and will always need time to complete your work. Clients may not want or be able to fulfil all your prerequisites. As a consultant you must be flexible and often ingenious in finding ways to complete engagements without all the ideal things you think you need to do your work. However, whilst you may be able to compromise there are some minimal prerequisites that must be met. If the client cannot fulfil these prerequisites for the work, the engagement should not progress (see Chapters 5 and 12).

The existence of an opportunity, which meets the prerequisites outlined above, is the starting point for a sale. We are going to look at identifying opportunities and selling consultancy in detail later in the book (Chapter 5), but just because there are opportunities does not mean you will necessarily gain work. Clients have choices. There are many consulting companies, and there are thousands of individual consultants. For every opportunity there are also many possible obstacles to sales

What are the main impediments to selling consultancy? Here are some key obstacles to sales:

In the first two sections of this chapter I have explored the various prerequisites that must be met and obstacles that must be overcome in order to make a consultancy sale possible. It may be that after reading this list you think it is never going to happen. Don’t despair – these prerequisites are regularly met, which is proven by the vast volume of consulting sales that are made all the time. I have listed them not to put you off, but to enable you to align all your ducks in a row, painlessly.

On numerous occasions, I have seen consultants (including, on reflection, myself) making epic efforts to gain a sale, only to end up wasting time as one or more of these prerequisites was not met. This cannot always be prevented, but frequently the wasted effort is avoidable. It is often determinable early in the sales process that some crucial prerequisite cannot be met. Frequently, getting a client to answer a simple question like ‘what budget is available for this work?’ is enough to determine there is no real opportunity. Unless you have some power to change the situation, then you are much better off moving on to the next opportunity than working hard where no engagement will be available. I have never heard of a client deliberately wasting a consultant’s time – as it is their time too – but sometimes it can feel as if they are! A client may simply have not thought through all the implications of engaging you, or sometimes they value just talking to a consultant without committing.

Let’s explore prerequisite 2 from the list earlier in this chapter in more detail: the client has a currently unfulfilled need. This is the most complex and important item on that list, and the one that consultants spend a significant proportion of their time identifying and exploring. What sort of needs do clients have? Clients have a huge variety of needs and desires. I cannot write a list of all the possible client needs that exist, but I can place them into a short set of categories. These are not mutually exclusive, but the core needs clients typically fall into one of more of the following categories:

What a client tells you, when discussing their needs for consultancy, may provide a clear and complete picture of why they are considering your services. However, this is unusual. Most people have other grounds that they do not divulge. Sometimes they are embarrassed to tell you everything or maybe they feel it is better if some things remain confidential. They may think if they tell you the truth you will not do the work. Sometimes they do not tell you because they do not realise the information is relevant or important to you. Often they do not tell you because they have not analysed all the reasons they want to use a consultant and are not consciously aware of the grounds themselves.

Irrespective of the situation, you will usually start a consulting engagement with an incomplete and sometimes incorrect understanding of why the client is engaging you. In practice, this is neither always avoidable nor necessarily an intractable problem. But, generally, you are in a better position to fulfil the client’s needs if you understand what the hidden grounds are.

You may not understand all aspects of the client’s grounds for buying consulting because the problem is complex and cannot be easily fully explained without some time involved in the organisation. This involvement can only happen when the engagement starts. It is not unusual for understanding of needs and selection of approaches to fulfilling these needs to change as the consultant fulfils the engagement. This is one reason why it is often effective to start a large engagement with a smaller scoping exercise, when both the specific problem and nature of the client’s organisation are explored.

There are many other motivations for employing consultants which will not be immediately apparent when you are first engaged. Typical examples of hidden grounds for buying consulting include:

This is by no means an exhaustive list. The central point is to be alert for the true, covert motivations clients have for engaging you. The only way to understand the hidden grounds is by observation and entering into exploratory dialogue with the client. If you meet all their explicit needs, but never fulfil their hidden needs, you will not satisfy your clients – and often the hidden needs are more important than those explicitly stated. As all good marketers know, client satisfaction is a crucial element in a successful business. In Chapter 5 we will explore this further.

Having sold an engagement to a client, the subsequent challenge for a consultant is to continue to remain involved. There are many reasons why a client may retain a consultant, the most obvious being the need to follow on from a completed engagement. A less overt reason is that the client values the ongoing advice and support of the consultant. Much of the value of consultants can come in peripheral activities: extra value that the client gains simply by the consultant being around. This can be small tips, advice, problem solving, tools and so on.

New consultants often talk about their client as if it is always absolutely clear who the client is, and also use the term client and the name of an organisation interchangeably. As in ‘my client is XYZ Corporation’. Your fees will be paid by XYZ Corporation. XYZ is the client organisation, but you cannot interact, advise or have a relationship with an organisation. Your client is one or more human beings. There are many situations in which there is clearly one client, and you can be sure that the interests of the client and the client organisation are aligned, but often this is not clear cut. This can result in two related problems: firstly, the difficulty of identifying the true client, and secondly, conflict in the views of different stakeholders and clients.

You need to know who your client is because the client is the person (or group) who your consultancy is aimed at. The client is the person who will judge whether the consultancy has been successful or not. If you do not clarify who the client is you may never be judged to have completed your work successfully. A different problem is that without a clear-cut client different people in an organisation can legitimately ask you to do all sorts of work. Not having an unambiguous and single client can be compared to the situation in which as an employee you do not know who amongst a group of managers is your boss.

One reason for this lack of clarity is that there are often multiple stakeholders in a client organisation who have different views and interests in a particular engagement. Although it is theoretically meaningful to differentiate specifically between a client and other stakeholders, in reality the boundaries are not always clear cut. There can be a wide variety of interested parties in any consulting engagement. On some engagements this is a minor issue. On others, different clients/stakeholders can be in direct and explicit conflict over the needs and direction of a consulting engagement, with the consultant left like some UN arbitrator in the middle trying to resolve the dispute with limited resources. The conflict may be explicit, but sometimes it is hidden, which is worse, as the consultant can progress the engagement with one understanding and only in the latter stages when feeding back to one client comes against another stakeholder who denigrates the work.

Another situation arises when the person who engages you, who you take to be the client, is actually hiring you under the direction of a more senior manager. The senior manager is really the client. The person who engages you may not accurately represent the true client’s needs. This can lead to all sorts of misunderstandings and problems.

Different stakeholders are quite likely to have different views on what is required from an engagement, and even how the work should be approached. Some stakeholders may think you are the ideal candidate to perform an engagement, others may doubt your suitability to do the work. Various stakeholders will have all sorts of different decision-making criteria. Ideally, you need to clarify all of this.

Another source of confusion is the difference between a client and an organisation. A client is a tangible person. You can speak to them and through dialogue get an understanding of their wants and desires, needs and wishes, interests and foibles. An organisation is an abstract entity, and if such an entity can be said to have interests you can only determine them indirectly – by speaking to the staff and managers of the organisation. Problems arise because the interests of the individuals in the organisation probably never align with those of the organisation. Even if a member of an organisation’s staff is trying to be objective and ignore their own interests, they will be constrained in achieving this by their biases, inherent assumptions and lack of full understanding of what the interests of an organisation are. One reason for clear and simple vision and mission statements in organisations is that all staff can then determine what the interests of the organisation are and are not.

We are therefore in a situation of imperfect information and limited consensus. One of the tasks a consultant initially has in any engagement is not only to understand the client’s wants and needs, but to clarify who the client is. Ideally there is one clear client who has the remit and authority to describe exactly what you should do. In practice, this is not always achieved. Power in organisations does not always fit the organisational hierarchy, and you will not always be so lucky as to have one main stakeholder in your work.

Why is this a problem? Because a lack of clarity over who the client is, and no real understanding of the client’s need and desires, leads to all sorts of other difficulties. Your engagement may be perceived as a failure if you please one person you perceived as a client, only to find someone else – who is really the client – is displeased. You cannot complete an engagement successfully without understanding client needs, which you won’t do if you have not identified the client correctly. You may have difficulty finishing your work as you try to satisfy more and more client stakeholders. If you are working to a fixed fee, trying to satisfy everyone causes you to lose money. There are many variations of these sorts of difficulties.

How can you solve this issue? There is no foolproof way to resolve it in every situation. Your role as a consultant may be explicitly to help reach consensus between all stakeholders. But it will not always be, and even if you are there to drive consensus your role can never be to sort out all the differences of opinion in an organisation. However, you do have to achieve at least a sufficient consensus to be able to complete your engagement effectively. There are five main steps to achieving this:

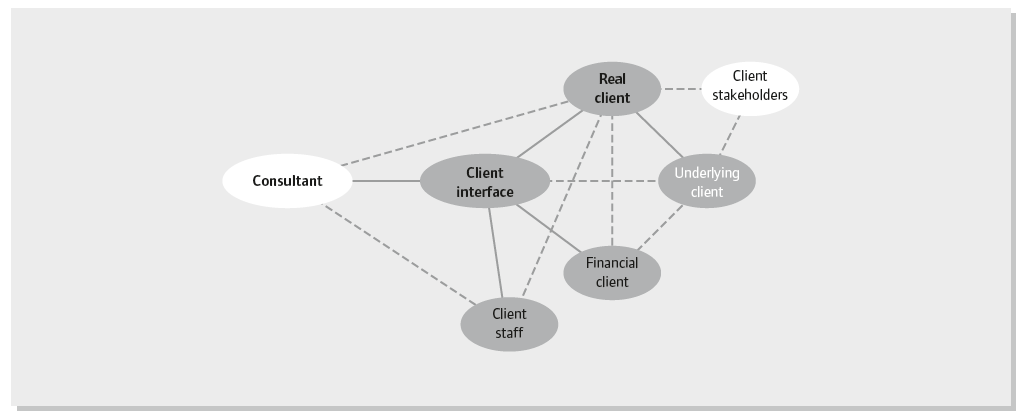

We will look at the points in this list again in Chapters 5, 9 and 10. For now, I want to focus on step 2. Who might your client be? This will vary from situation to situation, but the choice of the person who is your client starts by considering the person who first engages you. Typically you will be approached by an individual about the work the client organisation wants performed. This person may or may not be the ‘real’ client. I call this person the client interface.

Another possible client is the manager who has instructed the client interface (usually a more junior manager) to engage you. In some situations, it was a personal decision of the client interface to engage you, but it is quite common for a more senior manager to direct the client interface to hire a consultant. This senior manager is the real client. Ideally, you want to develop a direct relationship with this person, as they are the one who really wants the work done and are likely to be the judge of its success.

There will often be senior managers or executives with no direct involvement or interest in the work you do, but who influence the work indirectly by being concerned or even assessing the performance of the manager who engages you. This is the underlying client. The underlying client is important, as in the end this is the person or group your real client mostly responds to.

There are budgetholders and approvers who need to be convinced before you invoices are paid. You are a commercial business and need to be paid for your work and therefore must be comfortable that such people will authorise your invoices. Usually the person you work with as a client is also the person who authorises your bills for payment, but not always. Whoever authorises your bill is the financial client. The financial client is important as of course you want to get paid!

Finally there is a whole host of other client staff who review, approve or may simply be asked an opinion about your work. They may also work for you on the engagement. Such staff are not really clients, but you cannot ignore them as they have the ability to influence the judgement of your client both positively and negatively.

Behind these various people lies another group, who will be more or less important depending on the nature of the engagement. These are the client organisation’s stakeholders. These include external groups who may have an interest in the work, for example shareholders and owners, and for some industries, regulators. Many consultants never interact with these groups, but for some consultants they are a major influence on the success of the consulting engagement.

A typical set of clients is shown in Figure 2.1. The solid lines represent typical direct relationships relevant to the engagement. The dashed lines represent other possible relationships relevant to the engagement.

When considering this set of clients and stakeholders the following points should be taken into account:

Figure 2.1 Clients

Figure 2.2 The full range of stakeholders

This chapter has covered some of the fundamental challenges in consulting. It is important to understand these because as a consultant you will face them all on a regular basis. Hence I want to give you a brief summary to ensure the key points are remembered. Each of these challenges is explored in more detail, together with ways to overcome them, in the rest of the book.