In order to work as a consultant you must decide what service you are going to offer your clients, which is the main topic of this chapter. Confidence that the service is viable comes from understanding who your potential clients are and what they need (see Chapter 2). The central lesson from the last century of marketing is to start by focusing on what clients want, rather than what you would like to sell. This lesson is at the heart of client-centric consulting. However, whatever clients might want, your service has to be based on something you are capable of delivering.

Experienced consultants know that some clients, with whom you have a strong relationship, will hire you because you are a competent person who can turn your hand to many things. However, if you do anything and everything for one client you cease to be an independent consultant and effectively become part of the client’s team. If you simply want to generate revenue this is not necessarily a problem, but it is a risky strategy. You will become reliant on one client, and if this is really what you want, go and get a job as an employee of that client. If you do not, sooner or later your client will cease re-engaging you. In order to avoid this risk you want to be hired by a variety of clients, each for a limited period of time. In turn, to achieve this you must have a skill set, competency or capability that will help them to overcome problems they have. Even internal consultants want to avoid the situation in which they work for only one manager, and want to help a wide variety of managers in the business.

Many consultants do not have a specific service line as such, and drift from engagement to engagement as opportunities arise. Some consultants manage to keep themselves highly utilised doing this, but it is not the best approach. Like walking past a shop that sells different goods each week, clients do not know why they should specifically come to you. The times when clients are willing to pay the highest rates are when they have a pressing issue which they perceive a limited number of people can resolve. If you want to charge the highest fees you need to be able to differentiate yourself from the mass of consultants and contractors. One important way to create differentiation between yourself and other consultants is to have an area of specialisation. This is your consulting service.

The challenge with services is to know what they are and how to deliver them, but it is equally important to be able to position them with clients. It is no good having a service that clients do not understand or do not think that they want. There is also the classic business trade-off between being a niche player or offering a more generic service. This trade-off is essentially between:

Highly specialised skills have limited competition, but potentially limited need. When they are required they may generate high fees, but there is a risk that the market can evaporate. A service line in year 2000 compliance was hugely profitable in 1999 and many consultants joined the frenzy. On 1 January 2000, when the year 2000 problem was shown to be insignificant, the service became unsellable.

Generic skill sets may always be in demand, but there will be many consultants with similar skills. Whilst you may always be able to find work, the fee rate will tend to be lower. Project management skills are very valuable to clients and almost all clients run projects regularly. There are, however, many skilled project managers and unless you can differentiate your skills, the rates will tend to be relatively low.

The obvious starting point for developing your service line is to think through what skills, experiences or capabilities you have. What can you currently do? If a client asked you to tell them, briefly, what you can do, what would you say? Not only should you think about what you currently know, but also what you want to do. Most of us can do many things that are not forms of work that we actually want to do.

My first piece of advice when thinking about service lines is to relax. New consultants often become overly stressed with the thought that they do not have any skills that are sellable. You almost certainly do. Clients always need help and always have problems. You do not have to know everything or to be a world expert in anything to be a very successful consultant. There are very few world experts. Most clients do not need world experts and cannot afford them. Clients need competent people who can help them to resolve the issues that they have. To be able to help someone you must know more about the problem they are trying to resolve than the client does. In some situations, one or two pieces of information may be the difference between being able to add value and not being able to help. In saying this, I am not implying that all you need to be able to do as a consultant is bluff your way with some buzz words. However, if you are a competent and capable person, you do not always need to know a huge amount about a specific problem to resolve it. You just need to know enough.

If you have already had a career or some work experience in one or more industries, you already have knowledge and skills that will be useful to some clients. Clients are looking for people who can do one or more of the following:

There are a series of questions you can ask yourself. How can you make a client’s life easier? What sorts of common problems are you well positioned to solve for them? What functional knowledge do you have – are you an HR, IT or some other specialist? What sector knowledge do you have – do you know about banking or the defence industry? What services or specialisations in business do you know about – regulation, health and safety, software development or accounting policy? Who do you know who might be useful to clients? Try jotting down answers to these and similar questions and see if any pattern of knowledge arises, or if there are areas in which you have real skills. As a consultant you should not be seeking to be a master of all trades, nor do you need to be better at something than all clients. You merely need to find areas where you have a comparative advantage over some clients.

If you do not think you have sufficient skills to either present a service line credibly or to be able to do it in real life, you can always try to expand your skills. Everyone is capable of learning at every stage of their lives. There are millions of good business books and a huge amount of free online information. With some research you can pull together a body of knowledge that will be useful to some clients. However, I do caution you to understand the difference between being able to bluff about a subject and win some work, versus really being able to do it. Additionally, there are many good courses and training opportunities. Finally, you can always go away and study for a relevant degree or an MBA.

However, don’t be fooled into thinking that with some qualifications the floodgates of work will open. Clients primarily want intelligent but practical people, not academics or people with 101 qualifications and accreditations. I am not belittling the value of qualifications or accreditations, or the intellectual rigour of a good academic. I am merely saying that clients who buy consulting are typically only moderately impressed by such things. There are situations in which the advice of an academic is valued above that of other consultants, and some academics do have lucrative consulting practices, but few generate an income as significant from consulting as a successful professional consultant.

Having a specific qualification can provide a level of differentiation, but clients are really looking for a proven ability to deliver recommendations, develop realistic plans or implement change, relevant to their specific context or environment. Clients may require qualifications in certain specialised areas, but do not be fooled into thinking that a string of great qualifications will win you any consulting work. Clients are mostly interested in track record. A few credible past clients who will willingly provide strong, pertinent references will sell you more work than any qualifications. By all means seek qualifications if you believe you will learn valuable ideas whilst doing them, and no doubt qualifications help in being selected for recruitment into permanent roles. But a consultant is not being looked on as a permanent recruit: no badge or title alone will give you any consulting work.

The exception to this is the situation where there is some barrier to entry or highly recognised differentiation. There are many people with MBAs, but there are comparatively few with well recognised MBAs. A Harvard or INSEAD MBA, rightly or wrongly, still – and probably always will – impress. There will always be a limited number of people with the best qualifications. There are also other types of ‘accreditations’. For example, if you want to work in sensitive areas of government you usually have to be security vetted. Vetting can be a tedious and long-winded process, but once you are vetted you have a competitive differentiation above anyone who is not. Those who have not been vetted are effectively barred from some types of government work.

The best way to develop the right saleable skills is to deliberately go after consulting engagements that make you credible in that field. If you want to be an expert in setting up data centres or in providing strategic advice to the directors of charities, then the best place to start is by setting up a data centre or working on a strategy for a charity. There is of course a potential vicious circle here: ‘I can’t do work X because I have never done any of work type X, and I have never done any of work type X because I can’t do it.’ The answer is to start with realistic expectations. You cannot expect to be taken as competent in a field you have never done any work in – so when you first work in an area you must start at a relatively junior level. On the other hand, many areas of specialisation underneath the hype and the jargon are similar to others. The secret is therefore to do two things when interacting with any client:

Whatever age you are and however many years you have worked in one industry, there is nothing stopping you presenting your years of experience in the way that is most appropriate for a different sector or service line. There may be difficulties in learning new skills and capabilities at any time, but most are in the mind or about personal attitude and can be overcome. We all can, to a large extent, invent ourselves and continually reinvent ourselves in the way we want.

One way to develop a successful consulting business is to get into a new area of consulting first. If you are first into a specialisation there is no competition, and there are no recognised qualifications or experts. You are the guru by default. Spotting trends in management thinking early can be very lucrative. Relying on a trend is risky, as the market may never take off, but management as a whole is prone to fads and fashions. Some of these trends are vacuous and blow away within a few months or years. Others have a lasting impact on the way management is done. If you successfully spot a trend and enter a market early, the potential is huge.

Winning work is not just about being competent – it is also about being credible. Competency is an objective statement of your capabilities. Credibility is the subjective perspective of clients and other consultants. Credibility depends on a whole host of factors, and one building block of a credible service is being able to position your skills relative to typical client needs. This enables clients to label you, and use the label to understand what you do, and ideally to think of other situations in which they can use your skills. If you have a skill or knowledge that is valuable, you have the basics to becoming a competent consultant. By positioning your skills as a consultancy service you can convert competency into credibility.

The most basic way to label yourself is as a useful pair of hands, or another head with which a client can enlarge a team for a short period of time. The typical situation is that a client is short of a resource for a project, and you can fill the gap. Whilst there is nothing wrong with project work, this type of positioning should be avoided. There are exceptions, and I am not saying don’t do project work, just don’t label yourself as a useful pair of hands. This is the route to low-fee contracting work. It should be avoided for two reasons. Firstly, you can probably do very similar work, but position it in a different way and fulfil a differently perceived client need and significantly increase your fees. Secondly, there is a lot of consulting work, often the most interesting and lucrative engagements, that is not available to people just because they are a useful pair of hands. To win it, you must be perceived as a skilled consultant.

A useful way to think about how you position your service is against three dimensions which consulting services can be categorised into:

The sector is straightforward to understand. What is the industry sector your skills are most relevant to? You can position yourself as an expert in financial services, the public sector, manufacturing or telecommunications to name a few. Often clients are not only looking for skills, they are looking for skills that are relevant to their industry. For example, billing in telecommunications is different from billing in other industries – if you want to work on billing systems in telecommunications you must have telecommunications experience. Similarly, financial regulation is specific to financial services, and even to sub-sectors within financial services. You must have relevant sector experience to successfully position yourself as a consultant in financial regulations.

The service line you work in is akin to a function in an industry, but is somewhat broader. You may be a specialist in IT, HR, regulations, operations management, project management, performance improvement or something similar. Many service lines are common to most industries. For instance, all businesses which employ people, irrespective of the sector, have HR needs and can be helped by HR consultancy.

To win some consulting opportunities requires both a service and a sector specialisation. In other situations you need either sector or service line experience, but not both. For example, staff performance management processes and systems are relatively non-sector specific. A specialist in staff performance management should be able to work across sectors. However, a business strategist is likely to require detailed sector-specific knowledge to understand the competitive situation and market trends.

In general, the more focused and rare your specialisation, the higher the fee rate you can charge but the higher the risk of finding no opportunity. It is important to understand this is a very rough generalisation and there are many exceptions. Some consultants I know have very unusual skills, but there is enough work to keep them permanently busy at a high fee rate.

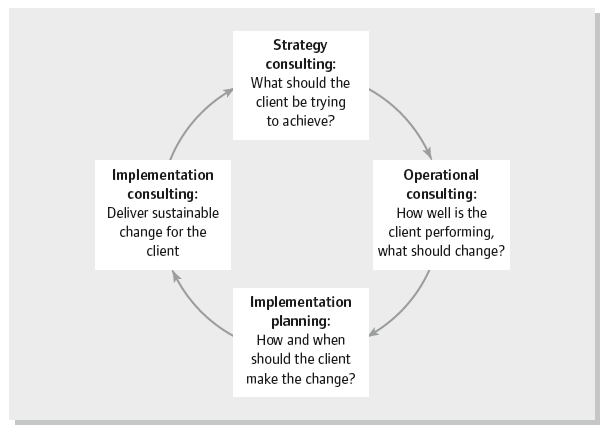

The last categorisation is what I call the phase in the change lifecycle a consultant works in. I will discuss change more in Chapters 4 and 8, but in essence all consulting is about change. Whether it is providing strategic advice through to helping in an implementation project, the outcome from consulting should be that something has changed in a client organisation. It may be that a better decision has been made, a manager has improved skills or a more fundamental change has occurred in the business.

Change is complex, but it can be thought of as a lifecycle. The lifecycle is an endless loop and therefore does not really have a start point, as change never ends. But we can think of the lifecycle for an individual change starting with an idea or concept. The idea can take the form of a definition of what an organisation should be trying to achieve. Consulting associated with defining why and what an organisation should seek to achieve is called strategy consulting. Having decided what direction the business should be going in, the actual operations of the business can be assessed to determine how well it is performing relative to the strategy and what should be improved. This is operational consulting. Having identified possible improvements, change initiatives can be planned to deliver the improvements, where a plan defines what and how the change will be made. This is implementation planning. Finally, a planned change can be delivered, with a sustainable change made to the organisation. This is implementation (or delivery) consulting. Once change is achieved the business is in a new state, and this cycle can start again. This lifecycle is shown in Figure 3.1.

Typically, the more closely a consulting engagement is related to strategy consulting the more important specific sector expertise becomes. The more a consulting engagement is related to implementation consulting the more important specific service knowledge becomes. However, this is a very broad generalisation.

Some organisations with consultancy businesses, including many of the largest companies, offer a range of additional services beyond those of pure consulting. As well as supporting change implementation they offer software or other technology development services. Such organisations will offer to run some parts of the organisation’s ongoing operations, which is usually called outsourcing. Consider a client organisation that wants to improve customer service. To make this improvement, the client organisation needs to set up a new customer call centre. The call centre needs new computer systems and staff. Some consultancies not only help with the identification of such problems and manage the implementation of the resultant changes – they may also offer to develop new IT systems for the call centre and to set up and run the call centre for the business. This is shown in Figure 3.2. This figure also positions how contractors and interim managers relate to this change lifecycle.

Figure 3.1 The change lifecycle

So far in this chapter we have looked at consulting services where the consultant provides recommendations or implementation skills – in other words the consultant helps the client directly. The relationship between the consultant and the client is one where the consultant tells or advises the client what to do. This is sometimes thought of as a teacher–student or doctor–patient relationship. There is another style of consulting, which we will explore in more detail in Chapter 7. This is where the consultant does not provide the client with direct recommendations, but instead helps the client to help themselves. This is sometimes known as process consulting (and must not be confused with process design or business process engineering, which it has nothing to do with). Another name for this type of consulting is facilitation. A facilitator does not provide a client with a solution to a problem, but instead helps the client to identify and solve the problems themselves. A major advantage of facilitation is that clients are much more likely to accept the result from a consulting engagement when they have developed it themselves. Coaching and mentoring can also work on a similar basis.

Figure 3.2 Relating consulting services to other service offerings

All the points made in this chapter should influence how you should position yourself as a consultant. Do you want to be seen as an expert in a sector or service line, a strategy or operational consultant, as someone who can plan change, a specialist in implementation, a facilitator – or some combination of all of these? Making your choice is not about closing doors, as there is no reason why at different times, even within the same client, you cannot swap between the roles – but clients like to and probably need to be able to label you. What you want them to do is to label you in such a way that you have access to, and are seen as a credible support in delivering, the broadest range of high, value-adding opportunities.

Success as a consultant requires a market for your service and it must be a service for which someone is willing to pay a day rate that will give you a sensible return. We will deal with finding clients and selling to them in Chapter 5. At this stage I want you to consider sales only conceptually. What do you need to have in place for clients to understand and accept your services?

The first thing to remember is that you are not selling to yourself. You are selling to a client. It does not matter how wonderful you know your service to be, what matters for selling is only what clients think. Clients have to need or want the service you are offering, and to understand it. Contrary to the opinion of some novice consultants, few clients are impressed in the slightest by obscure jargon and incomprehensible services. Clients are looking for a number of things, which can be summarised with a list of words starting with ‘c’. Are you: capable, competent, coherent, credible and client-centric?

How will you explain the value you can bring to a client and the specific service you can provide? There is a big difference between what you know you can do, and a saleable proposition.

I like to think in terms of pigeonholes. A pigeonhole is the name given to a compartment in which mail is put in an office when it is separated out according to department or even individual. The expression has come to be associated with a way of labelling people. In work we can be associated with pigeonholes relating to our skills, ways of interacting and relationships and groups we belong to. I could be pigeonholed as ‘a management consultant’ or ‘an author’ for example.

Pigeonholes are often seen as overly restrictive and generally a bad thing, but they are useful. We all need them, especially at the start of a relationship. Pigeonholes provide a short-hand for what we can do. No one remembers all of a CV or list of qualifications, but people do remember things like ‘great strategic thinker’, ‘reliable project manager’ or ‘dreadful team player’. These labels are easy to remember and they stick. We are all much more complex than a few simple phrases and none of us likes being pigeonholed. The secret therefore is not to let it passively happen to us, but proactively to choose the pigeonholes we want to be put in. We can do this in the way we consistently and coherently communicate to clients.

This is one reason why I put coherence as something clients need to see in your service. If you are incoherent about how you label yourself, or you position yourself with labels that do not seem to fit together coherently, then irrespective of whether the labels are true or not clients will not accept the pigeonholes you want to give yourself. For instance, let’s imagine the pigeonholes you want are ‘great high-level business strategist’ and ‘fantastic C++ software programmer’. If you happen to be a great high-level business strategist and a fantastic software programmer, so what? Does any single client need to know this? No. Worse, the labels are not complementary and reduce the credibility of each other when put together. They do not seem to be a coherent pairing of labels, even if they do happen to be true. The client who buys you as a corporate strategist and the one who buys you as a software programmer will usually be different people. Keep them as separate pigeonholes for separate clients.

I cannot stress enough that you should not position yourself as a good person who can do anything. Being positioned in the ‘jack of all trades’ or ‘useful pair of hands’ pigeonholes will not lead to you getting the highest value consulting work. You may sometimes sell, but high rates are paid to people who have skills that fit a specific client issue, not to people who just happen to be useful. Good consultants avoid presenting themselves as a jack of all trades. The talent is to present your skills broadly enough to be attractive to clients for a variety of work, but narrowly enough to be a credible supplier of specialised services.

The truth is, of course, that many of us actually have at heart a pretty generic skill set. Do not despair. Even the most basic and generic of skills can be labelled in an attractive way that differentiates and enables you to charge your clients higher fees. For example, my core consulting skills are related to project and change management, which is probably as generic as you can get in consulting. There are thousands and thousands of consultants who have or claim to have a similar skill set. If you have such a skill set you should seek some differentiation by adding on sector-specific knowledge, or experience of specific types of projects. The day rate for a generic project manager is several times lower than an experienced consultant programme manager with knowledge of a specific industry or type of project.

Although you have a set of skills that you can use to link yourself consistently to every opportunity, you should try to position your skills as uniquely relevant to each and every opportunity. One common vehicle to explain your skills and services is the CV. The novice thinks of the CV as a list of experience and qualifications. The experienced consultant knows a CV is a sales tool. As such, it has to be tailored to the sales opportunity. A client is never looking for the cleverest consultant in the world. A client is looking for a consultant with sufficient relevant experience to be able to help with their problem.

I have a master CV on which I have listed every single project I have ever done and every company I have ever worked for. No one sees this, except for some consulting associates I trust. Apart from the fact that it is far too long for most clients, it does not provide a simple, easily understandable and consistent picture of what I can do. I think it shows strong experience – but it shows that I can do too many things! Hence, when I have an opportunity that requires me to send my CV, I tailor it to the situation. I do not lie or make things up, but I stress the relevant areas of experience, and equally importantly I remove work that is not relevant. Even if you really are a master of many professions, clients will not believe you are. The impression from a CV with many different skills is not of a specialist who can do several things but a jack of all trades.

However broad your skills are, the route to success is to find a niche that suits you, or identify a market that is not adequately serviced by consultants and to develop those skills. Of course it is worth having more than one string to your bow, but only because it reduces the risks of not finding work and not because it will make you more attractive to a client in any one specific situation.

Once you have identified the services you will provide, do not think that you never need to reconsider them. Irrespective of how leading edge your services seem, you need to be flexible and constantly reinvent yourself. Service lines move on. For example, years ago no one asked if a project manager was qualified. Now there are various accreditations in project management and soon there will be chartered status for project managers in the UK. Software package like Baan or PeopleSoft were all the rage for a while, and a Baan or PeopleSoft consultant could have earned a good income. Who hears of them now? Business process re-engineering was something different and highly paid in the early 1990s; now it is a commodity skill that many consultants have. As a graduate from university I was initially trained as an MVS systems programmer. Many current readers will not have the vaguest idea of what that means.

Positioning services may seem to be something to consider only for the novice consultant. It is true that when you have worked with a client and have a great relationship with them your specific service lines are less important. But you can never rely on one client – you will always need new ones. Even if you trust an individual client manager to employ you on a constant stream of engagements, you do not know what will happen to their business in future. Even chief executives get fired or fall out with their boards sometimes!

One way to create a truly differentiated service from other consultants is to develop some intellectual property (IP). For consultants, IP consists of ideas or approaches to solving consulting problems that are unique to the consultant and which the consultant can control access to. Intellectual property can be methodologies or may be data such as benchmarking data. Some large consulting firms invest heavily in IP or intellectual capital to differentiate themselves from other firms.

A consulting organisation’s methods, tools and processes can be valuable and undoubtedly provide a certain amount of differentiation. They are particularly valuable when new ideas in management arise. The first consultants with a defined approach to implementing these new management approaches can win significant business, often at premium rates. Six sigma has now become a common tool, but when it first arose those consultants with six sigma methodologies could charge a premium rate. However, generally I am a little sceptical about consulting IP for the reasons noted below.

First, IP ages very quickly. Knowledge is inherently transferable and in the long run impossible to protect. If you are a manufacturing company, you may have some secret or patented manufacturing process, and you can probably keep this secret from competitors for some time. The fundamental problem consultants have with IP is that there is an inherent conflict between having unique knowledge and being a consultant. As a consultant you are paid for your skills and knowledge because you share them with your clients. Once you have shared your ideas they are out in the open. You may have only shared knowledge with one company, but client staff will move on to other firms and take with them any good ideas you have taught. In large consulting companies you may only train your staff in your IP, but consultants very often move from one consulting firm to another, and cannot avoid taking concepts and ideas with them.

The second point I make about IP in consulting is that there is actually very little of it around, at least much less than consultants claim. Certainly, if I apply the true legal definition of IP I am doubtful that very many consulting approaches would meet this definition. Much IP is more about branding and consolidating knowledge than it is to do with the creation of really innovative thinking. For example, many consultancies have different approaches to ERP (enterprise resource planning) implementation. These approaches may be valuable, have been developed from many years of hands-on experience, and enable a firm to implement an ERP system more rapidly and at a lower risk than those without such a methodology. But if you look at several companies’ approaches to ERP implementation there really is not a huge amount to differentiate between them. It is a mature market. No doubt some people do it better than others, but everyone involved in this type of service knows the steps to follow to implement an ERP system.

If you do have some IP, don’t be paranoid about losing it. If your IP helps you win work or to deliver assignments, then great. But clients are not paying to have access to your IP. They are paying for your ability to deliver great consulting. No client thinks ‘wonderful consulting, they shared their IP with me’, clients judge success in much more tangible ways: ‘I can make better decisions now’, ‘my strategic direction is clearer’, ‘I have a realistic implementation plan’, ‘that was much faster than I could have done it’, or ‘the change was implemented well’.

Don’t be afraid about your IP leaking to other consultants. A consultant with no experience and no relevant skills cannot pick up a piece of consulting IP and deliver a value-adding result. Intellectual property in consulting provides differentiation, enhances approaches, speeds up progress and reduces risk. It never removes the need to have skilled consultants. I have written many of my ideas in books which are widely available, but I am still certain that I have a set of skills that are valuable to clients and which cannot easily be found in other consultants. It is not that I have deliberately left things out of my books; it is simply that many factors in being a great consultant are more intangible and come from my ability to apply knowledge – not simply that I know lots of things. If consulting was just about knowing lots of information then the internet and services like Wikipedia would have already removed the need for consultants altogether.

The final point about IP is that you can develop it as your experience grows. You do not need it before you undertake paid work. You need to be careful from an ethical viewpoint that you are not claiming you have a methodology you have not yet fully developed. But within reason it is acceptable to create it as you go along. To some extent you have no choice. Consulting approaches and methods are based on experience, as this is really the only way to gain a method that is of any proven value.

Successful consultants build a profitable consulting business by thinking from the client’s viewpoint and developing service lines that are meaningful to the client.

As a conclusion to this chapter it is worth reflecting on the following question: how can you know that you are developing the right services? The proof that you have chosen the right services can only come from experience. If you have chosen the right service and are actively seeking clients, you should find that:

If you are not busy enough then it is quite possible that you need to rethink, sometimes only in minor ways, what the service is you are offering or how you are positioning it with your clients.

Let me end this chapter with a final thought about the skills you require. In addition to the specialist skills you have, you need the skills of being a consultant. A good consultant is not simply a bundle of knowledge and capabilities about some area or another. This is essential, but it is not enough. A good consultant knows how to be a consultant, and this is what the rest of this book is about.