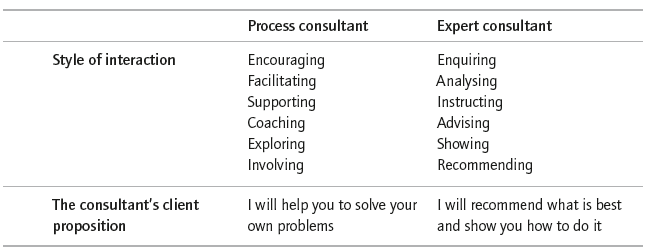

Table 7.1 Process and expert consulting compared

When many professionals imagine a good consultant, they often picture someone who is an expert in a field and who can advise clients on all the important aspects of a particular subject. Thus they may conceive of an IT consultant who knows all about technology and the latest trends and advances, a strategy consultant who understands everything about a competitive market and how to help a client redirect their business, or a manufacturing consultant who is aware of all the ins and outs of designing a factory floor and running efficient production lines. Such consulting is called expert consulting. Expert consulting is hugely valuable to clients and is the basis of much of the success of the management consulting industry. The big consultancy firms advertise their expertise in all sorts of areas. The many small consulting companies and thousands of individual consultants can provide in-depth know-how in almost every niche of business and management.

Helping clients by providing them with access to deep subject matter expertise is not the only value-adding way of consulting. Many consultants use another method to assist clients that is radically different, and does not require them to position themselves as subject matter experts. This is process consulting.

The term process consulting may be unfamiliar to some readers. Throughout this chapter I use both the terms facilitation and process consulting largely interchangeably. Facilitation is a term usually preferred by clients as they are familiar with the word, whereas process consulting is a phrase or jargon more commonly used by consultants themselves. I tend to use the term process consulting, as I think it is a more precise definition, it derived from the pioneering and still valuable work of Edgar Schein (see page 280). Whilst I have been influenced by the writings of Schein and others, this chapter contains my own interpretation of process consulting. Clients may also think of process consulting as coaching, as the experience of process consulting is more akin to being coached than receiving expert advice.

Not all consultants understand, are comfortable with or proficient in process consulting. It is an approach that focuses more on a client’s own willingness and ability to define solutions, to learn and to grow, whilst working with consultants, than on the direct subject matter expertise of the consultant. It is often seen as an easy way to consult, but in reality true process consulting is hard, and can be extremely demanding on clients and consultants alike.

The implicit bias so far in this book has been towards expert consulting, and this chapter seeks to redress the balance by discussing process consulting as a fundamentally different way of consulting. It is a complex topic that cannot be fully encapsulated in one chapter. Process consulting is a practical skill and is best learnt by doing it and receiving feedback rather than by thinking and reading about it. In this chapter I provide an overall description of my perspective on process consulting to give a general understanding of the approach. I describe the advantages, I compare and contrast it with expert consulting and explain which method is better in which situations.

Every activity can be split into two parts – the content of the activity and the process of the activity. The content is the what, and the process is the how. Usually with consulting the activity is to resolve some kind of problem or issue. An expert consultant is focused on the content and sometimes the process of solving problems. The expert helps describe how to resolve a problem and usually advises what the best solution is. A process consultant looks exclusively at the process. Scoping and solving problems is the responsibility of the client, with the guidance of the process consultant.

What is meant by ‘process’ in this context? This can be shown by examples, starting with a business meeting. It has some content – that is the subject that the meeting is about, the various information and arguments that are made at the meeting, and the conclusion or outcome that is reached. The meeting also has a process, for example, the process might be:

None of these points reflects the nature or content of the meeting, they are all about the process by which it is managed. This meeting could be concerned with any topic. In this example, the chairperson is managing the process, but is not acting purely in a process consulting style. As well as managing the process, the list above indicates that the chairperson will make decisions about the content of the meeting.

Let’s consider a more complex task: creating a requirements specification for a new IT application in a business. An expert consultant would approach this by listing what they felt were the relevant requirements for this type of application, or even by telling the client what was the best software package for the situation. A process consultant would help the client to define the requirements themselves, by going through a process like the one below:

Again, none of these steps is about what the requirements are, they are all about helping a client by giving them structure to achieve the objective of defining the requirements. Whilst this can appear simple, there is a lot of complexity below these individual tasks. For example, a nominally simple task like ‘agree prioritisation criteria with the team’ may require great skills to clarify and combine different people’s views and achieve consensus on them.

In a way, the title process consultant is unfortunate, as it can be confused with a process designer, business process re-engineering or an expert in one process or another. It has nothing to do with these. But I prefer it to the term facilitator, because the latter is often misused and misunderstood. Facilitation and facilitator are often synonymous with help and helper respectively. Facilitators are much more than people who help in solving a problem. A facilitator has a specialist skill and applies facilitation techniques. These techniques focus on helping a client by managing the process. I tend to use the term facilitation when I am discussing a technique I might use in an individual meeting, workshop or set of workshops. Process consulting is the phrase I am apt to use when approaching a complete consulting engagement or a significant part of an engagement.

One way to understand the role of the process consultant is to compare it to the role of an expert consultant. Typically, an expert consultant tells (or, more politely, advises) a client what to do, or shows them how to do it. A process consultant helps clients to work it out for themselves. This is summarised in Table 7.1.

Process consultants and facilitators provide structure and focus to the process of discussion and problem resolution. They are responsible for achieving an outcome, but the client, or more usually a team of client staff, maintain ownership of the outcome that is achieved. Hence effective facilitation requires an understanding of the objective or outcome desired, a process to manage the discussion and communication skills, as well as flexibility, responsiveness and insight into group dynamics.

Workshops are usually an important part of a process consulting engagement. A typical objective is to determine how to overcome a problem or issue that a client wants to resolve. Often the objective is defined in terms of scoping a problem. Most of the work will be done with the client or client team in workshops. But there is some preparation work for the consultant in terms of designing a process to manage a workshop, and there are usually some post-workshop tasks such as writing up the outcome and making notes.

Workshops can produce a massive amount of unstructured material. One of the skills of the facilitator is to structure and summarise this material as the workshop progresses, but also to consolidate and write it up following the workshop. The structuring of workshop materials, which are often in the form of flipcharts and rough notes, is a crucial stage in process consulting. Process consultants must remain aware that they are facilitating and not leading. It is very easy when summarising information to put your own spin on it when you select what you think is most important and leave out what you feel is less critical.

The process consultant uses a range of approaches, tools and techniques. The first technique is to define a process to scope or resolve the client’s problem that is appropriate to the situation. The approach could be to run a series of workshops, each of which moves the client progressively closer to the objective desired. The process consultant also needs to plan how each workshop will run and who should attend. Once the workshop is running the consultant should be skilled in identifying and resolving conflict, as well as developing consensus in a group. The process consultant must be observant of the group and group dynamics. Judgement is also important: for example, if consensus is not going to be achieved, deciding when it is a sensible time to let the team take a break from a workshop versus making them continue to reach a conclusion. The process consultant must be able to structure information from many members of the team, and help them to see patterns in it.

Most of all, the process consultant has to have excellent communication skills, especially those related to listening and questioning. A large part of the success of a process consultant is asking the right question at the right time to encourage thinking, debate and sharing of ideas. The sort of questions a process consultant asks can be exploratory, diagnostic or action orientated. Irrespective of the style of question, they should be aimed at helping the team to explore, to think and to understand. Questions of the form ‘why do you ….’, ‘how will you ….’, ‘exactly what will you …’, ‘what is the situation in which …’, ‘what assumptions underlie …’, ‘does everyone understand …’, ‘do we have consensus …’, are common. The process consultant should avoid confrontational or leading questions (see Chapter 11). Using leading questions is not process consulting, but is really covert expert consulting. Leading questions can be hard to avoid, and often consultants ask them without realising that they are doing so. In asking questions, process consultants should observe as well as listen, looking for any indications that people are not being open or are not involving themselves in the discussions.

In managing workshops, the process consultant manages time and the environment the workshop takes place in. Workshops can easily fail because they run out of time to reach conclusions, and it takes skill to encourage a debate to progress, without controlling or steering the content of the group’s discussions. Correctly deciding when it is appropriate to take a break, and when it is not, has a significant impact on workshop outcomes. Similarly, the way meeting rooms are laid out, and the existence or absence of distractions, make a huge difference to the success of a workshop.

Process consultants must try to be impartial, and keep the client team focused on the objectives. Process consultants must build trust with the team, so that team members will allow themselves to be guided by consultant. The process consultant treats all members of a team equally and should ensure that all members are involved in discussion and reaching conclusions. Conclusions are ideally reached by consensus with the team, although in practice consensus is not always possible to achieve for some contentious issues.

The consultant is primarily concerned with ensuring that the client achieves an effective solution that is acceptable to them, but what the solution is and what the criteria for acceptability are, are completely up to the client. A process consultant should avoid assumptions or preconceptions about the situation. In contrast, expert consultants are independent in the sense that the recommendations they give are meant to be what the consultant determines are best for the client, irrespective of the client’s own viewpoint. An expert consultant must have preconceptions – that is the basis of their expertise. The word recommendation can be seen to encapsulate the difference, as recommendations lie at the heart of an expert consultant’s work, while they are the antithesis of a process consultant’s support for a client.

Table 7.2 summarises the main points in this section by comparing the role of a manager solving their own problems, to the roles of a process and an expert consultant in resolving a problem.

Some problems are obviously best resolved by process consulting. For instance, if there is a lack of consensus within a team, an expert giving their opinion on a solution may help with making a decision but is unlikely to help in achieving consensus. On the other hand, a process consultant is well skilled in helping to bring a team together and achieving consensus within the team. Many tasks can be supported by a consultant working in either a process consulting style or an expert consulting style. Hence the relevant question is: what are the relative advantages and disadvantages of the two styles?

There are some important reasons to select a process consulting as opposed to an expert consulting approach in some situations. Process consulting can be beneficial for the client on a personal level. It can result in greater acceptance of the outcome from an engagement, primarily because the outcome is the client’s. Process consulting can help the client to learn and understand more about an issue. The nature of process consulting is that a client or client team goes through the process of scoping and solving a problem, and is the primary participant in the consulting engagement. In contrast, in an expert consulting situation the client can choose to be an observer and simply read the recommendations at the end of the engagement. The level of a client’s personal involvement and development can be much higher during a well-run process consulting engagement than an expert consulting engagement.

Clients expect consultants to have expertise, and have often employed consultants to advise them. But it is not always appropriate to give advice. Sometimes a better solution is for clients to solve problems themselves. The problem with the external expert is that clients may reject advice or may not learn from the experience of working with an expert. A process consulting style is extremely powerful in getting clients to buy in to solutions – because the clients developed the solution themselves, and in doing so, the clients learn. Think back to your own childhood when you were learning. You can teach your children by telling them facts and giving them the answer to every question they ask. But teachers and parents know that a far better way to assist children to learn is to help them to understand and to think for themselves. Instead of simply telling children the answer to a problem, you can help them by responding to their request for help with questions like: ‘can you remember anything this is similar to …?’, ‘do you remember how you did this last time …?’, ‘what can you tell me about the problem …?’, ‘which parts do you understand …?’ By solving the problem themselves, children learn better. This advantage of self-discovery and understanding over being told answers does not stop in childhood.

Clients and client staff are often the best people to analyse problems and come up with solutions, as they are closest to them and understand them best. An external expert, unless they have spent extensive time working with a client, will always have an incomplete understanding of the context and culture of the client organisation, and of the details of how a client precisely does various tasks. Additionally, when clients have designed a solution themselves it is often easier and faster to implement.

There can be advantages to using process consulting from a consultant’s point of view, irrespective of the client’s needs. Process consulting skills can provide a way to help a client in situations in which you are not a subject matter expert, but still want to contribute value. It is common on many consulting engagements to find yourself in unfamiliar situations. For example, you may be invited to a meeting and find the topic is one you know nothing about. You can choose to stay uninvolved in the meeting and simply listen, but this is rarely acceptable behaviour for a consultant. You can bluff, but this should be avoided as it does not add value to the client and is risky to your reputation. A better solution is to accept you know nothing about the subject and to use a process consulting style. Sometimes asking questions as simple as: ‘are we all clear what the objective of this meeting is …?’, ‘how are we going to work together …?’, ‘do we need consensus or is a majority decision good enough …?’, can be extremely helpful to clients. In this way, you can still help the client, whilst your own understanding of the situation and content develops. If you do this well, clients will value your input and often will not even realise that you did not add any content to the meeting.

However, process consulting is not a solution to all consulting challenges, or one that will enable consultants to manoeuvre through any situation. For instance, it can be tempting to involve a junior consultant, with limited subject matter knowledge, in an expert consulting team and let them muddle through by relying on process consulting skills. This should be done with care. New consultants often have less deep expert knowledge, but they may also have no process consulting skills.

None of this section should be used to imply that process consulting is always the preferred style. There are many advantages of being an expert consultant. An expert consultant can bring an independent and unbiased view. Although the process consultant is unbiased and wants to achieve consensus, the solution is the client’s and may therefore suffer from any limitations in client thinking. An expert can help to break group-think. Critically, an expert can provide speed in identifying a solution. Process consulting, especially if it is used to achieve full consensus, can be very powerful, but it is not always quick. An expert can often immediately tell the client the solution to a problem. Clients also often want expert consulting. Whether it is right for them in the longer run or not, there can be an attitude with some clients of ‘just tell me the answer’. It may be appropriate to try and persuade them otherwise, but, in the end, if that is what clients demand, then as consultants our task must be just to tell them the answer. Finally, there are many situations in which an expert consultant is the only appropriate approach. For instance, if a client needs to understand the ideal way to overcome a technical or specialist problem they have no experience of, then no amount of facilitation will produce the optimal answer, whereas a skilled consultant who has seen this problem many times before will be able to identify the optimal solution easily.

There was a joke going the rounds when I first did a process consulting course that it was ‘content-free consulting’. In a way this is true, but not in a negative sense at all. It is content free, because it is meant to be, and whilst it sounds counter-intuitive to an expert consultant, the absence of content is the source of its value. A process consultant has a mature relationship with the client, in which the client is understood to be perfectly capable of understanding and resolving their own problems, but sometimes just needs a little help to be able to do this.

Expert and process consultants are sometimes presented as either/or ways to support a client, but in reality they are both valid and valuable ways to consult. The challenge for the skilled consultant is not to choose one or the other, but to be able to do both and to determine which approach is best in which situation.

A consultant who can switch between a process and expert consulting style needs to consider which approach to use in which situations. The choice should be determined by what is most in the client’s interest. For either approach, you need to start with an understanding of what the client’s issue is, and what are the client’s capabilities and needs to get to a solution. If the fundamental issue is that the client does not know what is wrong or how to define the issue, both process and expert consultants can define the issue. An expert consultant, based on previous experience, will tell the client what the likely issue is. A process consultant will work with the client to develop clarity in the client’s own thinking.

There are several factors to consider before deciding which style of consulting is best. Does the environment or culture of the client suit process or expert consulting? Some clients respond very badly to attempts to facilitate them, and do not employ consultants for these reasons. Other clients are passionate about facilitation and see it as an important aspect of a consultant’s role. Trying to use process consulting with a client who is not open to the approach is rarely successful. Conversely, always acting the expert when the client wants a deeper participation in the engagement and shaping the outcome is inappropriate.

Other factors to consider include the speed of resolution required by the client, the level of input and involvement a client can give to an engagement, and the level of consensus around the issue. When a client wants greater involvement, when the issue is contentious and consensus building is required, and when there is time, then process consulting is often preferable. However, if an issue is well accepted and a client wants a consultant to just get on and resolve it, expert consulting is usually better. There may be several opportunities to include facilitation and expertise within an engagement. It could be that the whole engagement is about process consulting or it may be that a part of the engagement is done as an expert consultant – either can be used at different times, and each style of consulting can be used by different members of a consulting engagement team.

Theorists, especially those with a bias towards coaching and facilitating, can stress the criticality of not mixing an expert with a process consulting mode. It is true that if you want an individual to learn and develop it can be crucial to maintain a consistent process consulting approach and to avoid ‘giving them your answer’ by switching into an expert mode. But within a consulting engagement life is rarely so clear cut. As described above there are many advantages of a process consulting style, and rarely is the client worried (and sometimes not explicitly conscious) about whether you are using a process or expert mode. You must make a judgement as to which approach to use on a regular basis. Even when facilitating workshops I sometimes switch into expert mode, although if I do this I make it explicit to my clients. Hence I may say something like: ‘I am going to be a little more directive now, is that OK?’ or ‘I would like to give some direct advice on the issue.’ This has to be handled with care as you can easily undermine your position as a facilitator. A solution is to use two consultants: one works as part of the client team as an expert member, and another retains the role of a facilitator.

Sometimes process consulting is used for whole engagements, but more often it is more powerful to use it in parts of an engagement. For example, I may facilitate a client to explain their requirements, to scope an issue and gain consensus in a client team about a way forward. But I may then act as an expert when it comes to advising the client on how to meet those requirements. Typical situations in which process consulting is frequently successful include:

Process consulting is more appropriate in some stages of the client’s change process than others (see Chapter 4). You can develop ideas and even help a client to develop plans via facilitation, but you cannot easily implement change or review operations as a process consultant. Similarly, different stages of the engagement process are more easily delivered as a process consultant than others. Process consulting skills can be especially useful as part of the exploratory dialogue in the propose stage of the engagement process, when an understanding of the client issue is required. If you choose to perform the deliver stage as a process consultant, it may require modification from that described in Chapter 6. For example, for a process consultant the consider and create steps of the deliver stage are not concerned with developing their own thinking and final reports, but with structuring and making sense of the client’s ideas and helping them to draw their own conclusions.

Another factor to consider in selecting the preferred consulting approach is your capabilities. Not all consultants are great process consultants, and not all need to be. But some level of facilitation skills are a strength for all consultants. An ability to differentiate between helping a client with the content of a problem and assisting them by managing the process is important. However, it is very irritating when you are advised that you will be attending a workshop run by a facilitator but the facilitator tries to stay in an expert mode and is really telling the attendees what to do and think. If you really cannot facilitate or process consult, then do not try.

Some situations require exceptional facilitation skills, especially when developing consensus around highly contentious issues. Expert facilitation is a specialisation in its own right. If a consultant is not a natural or talented facilitator, they should understand the situations in which a client needs an exceptional facilitator and, rather than doing the work personally, assist the client in locating such a highly skilled facilitator.

One thing a client is often looking for from a consultant is creativity and innovation in ideas. The approaches to creativity from a process and expert consultant are quite different, and in determining which approach to use it is important to understand what the client wants and needs. Consider the following examples of how an expert and process consultant will approach such a situation:

These are fundamentally different approaches to coming up with new ideas. A client may be open to both, or may be explicit in what style of help they require. If a consultant is going to use a combination of expert and process consulting, the decision of which approach to use and when can usually be determined as the engagement progresses. If the consultant will only use one approach, this is best agreed with the client before the engagement starts.

Both process and expert consultants should be independent of the client, and avoid colluding with the client. Collusion happens when a consultant gives a client precisely what the client wants, irrespective of what is right for the client organisation. Sometimes collusion is deliberate by the consultant, on other occasions it is unintentional and results from too close a working relationship between the consultant and the client. The way collusion occurs is different in process and expert consulting. Colluding with the client as an expert is telling them what you think they want to hear. Collusion as a process consultant is reflecting what the client has said without worrying about consensus or involvement of the rest of the client team. You can also collude with the client by posing as a process consultant, but then telling them the answer because they do not want the bother of being involved in workshops.

A related situation to collusion is when clients wash their hands of responsibility for an issue by handing it over to a consultant. This is more of a problem for expert than process consultants. Generally, consultants should not take full ownership of a problem; the client manager in the end must always retain ownership. When a client hires an expert consultant, the client can sometimes effectively delegate ownership to the consultant. This is when clients think, ‘it’s not my problem anymore because I have hired a consultant’. Clients cannot abrogate responsibility to the consultant in a similar way when using process consulting. Hence process consulting is not an easy option for clients. If it is done well, it can be enjoyable and exciting, but it does require the client to participate 100 per cent in the process.

Many consultants struggle with process consulting. They are often seduced by the content. The content may be interesting and also holding on to the content can seem comfortable. Positioning yourself as an expert clearly establishes your relationship and role with the client. Moving to a process consulting mode can feel risky, and you may get the impression of exposure at times, since the value you are adding is less clear cut. However, many clients deeply value good process consulting. It is not uncommon for a client to appreciate more highly the member of the consulting team who facilitates the client’s own thinking, rather than an expert consultant in the same team.

This chapter provides an overview of process consulting in contrast to expert consulting. Key points to remember are:

Process and expert consulting are summarised and contrasted in Table 7.3.