The core work of all management consultants is the delivery of client engagements. The engagement represents the time when a consultant’s specialist skills, knowledge and service lines are applied. This chapter describes the process of delivering engagements, together with many tips and techniques essential for great consulting, and is relevant to all consultants. It should be read in conjunction with Chapter 7 on process consulting and facilitation.

Some senior managers in consultancies are no longer involved directly in engagements, but spend their time in managing the consultancy, business development and selling work. This is purely for the commercial benefit of a consultancy. Of course, a consultancy as a commercial enterprise needs to be successful and profitable. However, it should not be forgotten that the primary source of that success is not in the way the consultancy is managed or engagements are sold, but comes from adding value to clients by delivering consulting engagements that meet their needs. A client-centric consultant always has client needs at the forefront of their thoughts, and a consultancy business should be structured and managed to optimise the provision of client-centric consultancy.

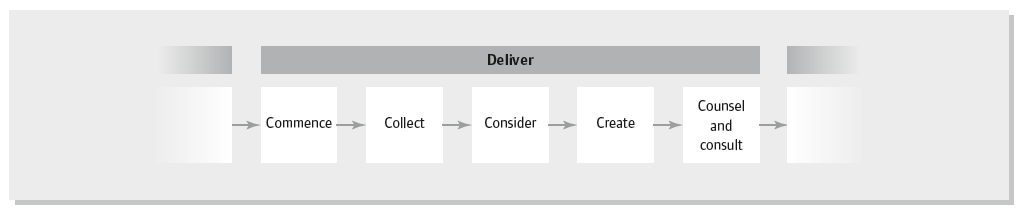

This stage of the engagement process is called deliver-to-satisfy, as the main objective is not just to complete a piece of paid work, but to satisfy the client. The steps within this stage are shown in a linear fashion in Figure 6.1.

Figure 6.1 The deliver stage

The linear structure in Figure 6.1 aids understanding but, in reality, this stage is highly iterative. Whilst a consultant must generally progress in a logical order from an initial commence step to a counsel and consult step, there will be regular jumping between the steps. For example, when a consultant is presenting a report to a client, they may realise the report has missed some vital point. The consultant returns to the create step and then further back to the consider step to revise their recommendations. In doing this, they may realise they need more data and have to briefly return to the collect step. In a complex engagement, there will often be a periods of simultaneous working across the steps in the deliver stage. Hence, in reality the process will look more like that shown in Figure 6.2.

This chapter is ordered in the sequence shown in Figure 6.1

Having successfully won an engagement, the first step in delivering it is the commence step. Commence is concerned with planning and resourcing the engagement. In order to do this a number of decisions have to be made. The direction and nature of these decisions will be shaped by agreements made and information collected in the propose stage, but normally it is only when an engagement is won that a fully detailed engagement plan is developed and named individuals are committed to working on the engagement.

Figure 6.2 Iterative working in the deliver stage

The nature of a plan for a consulting engagement depends primarily on the scale and complexity of the engagement. A large consulting engagement with many consultants working on it for several months may require the involvement of a dedicated and experienced project manager. At the other end of the scale, a small engagement with a single consultant working on it for a few days requires little more than an ordered list of actions that need to be completed. Most engagements sit somewhere between these extremes.

Project management in a typical consulting engagement is not complex, but consultants are often not great project managers. This can be seen in the stress and semi-chaotic rushing around that typify the end of many consulting engagements. The end is always predictable and a little planning makes even the most complex consulting engagement run much more smoothly. A good plan reduces risk and increases profitability. An effective plan makes the consultant seem more competent in the client’s eyes, and generally reduces the level of stress on everyone in the consulting team. I run courses on project managing consulting engagements, and I have observed that even very experienced consultants benefit from thinking more about planning their engagements.

You do not need a qualification in project management to manage a consulting engagement, but an engagement is a project, sometimes has complex logistics (such as aligning many people’s diaries at different times), and a degree of logical and systematic ordering of tasks is required. At some time, each and every consultant may have to deliver a consulting engagement on their own. Hence, all consultants must have the basic capability to project manage the consulting engagement. The basis of managing a consulting engagement is a plan.

An engagement plan needs to be comprehensive but flexible. Ideally, it contains every aspect of the work required to complete the engagement. However, typically in consulting engagements it is difficult to determine all the tasks required until the engagement is underway. Therefore the plan has to have enough flexibility to add new tasks as the engagement is performed, without increasing resources or the project timescale.

One feature that can make planning a consulting project more complex is that, unlike many other projects, the timescale and amount of consulting resource to be used is often agreed as part of the proposal, before the detailed plan is developed. This may seem to be an illogical ordering of activity, and it regularly causes issues, but it is not an insurmountable obstacle. The costs and timescales estimated in a proposal should only be done by someone with experience and with a realistic view of how complex the engagement is. Additionally, there is some leeway in most engagements to scale the deliverables from the engagement relative to how much time is allocated in the proposal. For example, a report on an aspect of a business can be developed in more or less detail, and with more or less information gathered, depending on the constraints imposed by the proposal. Of course, client expectations must be aligned with this scaling.

What differentiates a really good engagement plan from a weaker one is that it is begun by considering the end point of the engagement first. A good plan is developed by thinking through what the result from the engagement should be, and how to bring the engagement to an end. The plan is then elaborated by working backwards through the tasks that must be done to enable this result.

The result of a consulting engagement may be the creation of a set of client deliverables or some predefined outcome. A deliverable is a defined output which is usually tangible, but sometimes intangible, and which the client can utilise. Examples of deliverables include reports, presentations, training courses, process designs, plans, lists of recommendations and so on. An outcome is a change in the client’s business. Examples of an outcome include a 5 per cent reduction in the cost of operations, a decision made, or consensus achieved in the new strategy for a business. Traditionally consultants have been deliverable-focused, but increasingly are more outcome-orientated. By offering a client an outcome and not just a deliverable, it is possible to develop a better client value proposition and hence charge premium fees. It may seem a rather fine difference between deliverables and an outcome, but it is important to understand it whilst developing an engagement plan.

Let me illustrate with two hypothetical alternatives:

The former is concerned with developing and writing a report with a revised strategy in it. The latter entails the creation of the strategy report, but also requires ensuring all managers understand and agree with the strategy, and have the skills and resources to move ahead and implement it. The latter is a significantly more complex engagement, and as the consultant it is essential you understand the client’s expectation with regard to deliverables and outcomes.

Once you understand the outcome or deliverables wanted, the next stage in developing a plan is to define the consulting approach or the process you will follow to achieve this result. Some clients are only interested in achieving the agreed deliverable or outcome and do not care how you achieve it. Many want to, and you often need them to, understand the process which you will use to get to this result. You usually need the client to understand the process you will follow, because the client will be a participant in this process, and will have to provide resources to support you in going through it.

One critical decision to make is whether you will adopt the style of an expert consultant or a process consultant. Chapter 7 describes process consulting, and this chapter is primarily orientated towards expert consulting, although the boundary is not clear cut. The fundamental difference is whether you expect to tell the client what to do (expert), or whether you will work with the client so that they can define themselves how to resolve their problems (process). These are radically different ways of working. However, within a single engagement a consultant may switch between these styles at different points.

It is also important to understand the organisational scope of a consulting intervention. Are you dealing with the whole business, or will you look only at a subset of the organisation, for example, specific departments, divisions or processes? An engagement to look at the recruitment process in the sales department has a significantly smaller scope than one to look at all HR processes in sales, marketing and customer service. Consulting engagements are for limited periods of time, and to achieve a high-quality result it is usually essential to place some boundaries on the scope of the work. An unbounded scope requires an unending plan.

All engagements need an engagement management process. The engagement management process is the mechanism by which the engagement is controlled. It typically requires a series of client meetings for the duration of the engagement. Whenever I run an engagement, I like to meet my client every week to update them on progress, discuss any findings and resolve any issues getting in the way of progress. Similarly, if you work for a large consultancy, your management may require meetings to ensure you are maintaining the necessary level of quality in your work and are not exposing the consultancy to any unnecessary risk. Your consulting company may have some mandatory processes to follow as part of the engagement. If the engagement has a team working on it, the team normally needs to get together regularly to update on progress, align work and to resolve problems. The frequency depends on the nature of the engagement. On some very intense engagements I bring the team together on a daily basis, on others it is less frequent. The engagement management process is normally very simple, and essentially involves setting up a series of regular meetings with an agreed agenda with client, team and consulting management. Experienced consultants know that the trick is to make sure the meetings are agreed and arranged at the start of the engagement. If they are arranged on an ad hoc basis whilst the engagement progresses, you will soon meet delays as people will not have time in their diary to meet you.

A final factor in developing the engagement plan is to decide whether you need to include any risk management activities within the plan. Consulting engagements are subject to a variety of risks, including access to resources and the possible negative influence of some stakeholders upon your work. Many risks have to be dealt with as they arise, but some are predictable and it is worth considering what activities you will undertake to overcome them. Risks are many and varied. Risks can be identified by asking questions such as: what will you do if the client does not provide the resources agreed at the times agreed? If you are basing your engagement on some hypothesis about underlying problems, what will you do if your hypothesis turns out to be wrong? What will you do if you find out some influential stakeholder is opposed to your work?

Having developed the engagement plan, it is possible to determine what resources are required to execute this plan. The resources are mostly people. They will be consultants, but they may also be client staff. One frequent problem on consulting engagements is getting real client staff released to work on the engagements in practice, as opposed to a theoretical promise by a client to give some staff to help. This is one reason why it is worth agreeing this up front. If a client offers staff to work on the engagement, make sure you get commitment to named individuals with the necessary skills and time available to work on the engagement. But resources may be more than people, and you must identify what else you need to deliver the engagement successfully. Examples of other resources include transport, building passes, office space, facilities, access to specific areas of a business and so on.

Table 6.1 presents a short planning and resourcing checklist. The aim is to be able to answer ‘yes’ to every question in this table. For every question you answer ‘no’ to, you must determine what actions you need to take to resolve it.

Whatever approach you take to helping a client, you need to collect information. The information is required to understand clients and their issues, scope engagements, understand impacts and the seriousness of problems, and to identify solutions. Information must be available on engagements as the basis for analysis and sometimes to measure results. Information has to be developed. Data is collected, which will at first be unsorted, in various formats, and is often of limited value in its initial state. The data must be analysed and converted into useful and meaningful information. There are many sources of data and many ways it can be analysed. The specific approach depends on the type of consulting you undertake, and much of the skill of a good consultant is about the ability to identify pertinent data and to convert it into the most relevant information in a specific situation. In this book I focus on data and information in a generic sense – the details are situational specific and will depend on your service lines and the individual engagement.

Accurate and sufficiently comprehensive data is critical to the success or failure of your consulting engagement. You cannot draw valuable conclusions without a relevant sample of data. The data collected is also related to the way success is judged. There may be different and conflicting views of success depending on viewpoint and data collected. Ideally, you must take account of these different measures and viewpoints. It is common for consultants to stumble when providing results to clients who ask questions like ‘have you considered …?’, or ‘did you speak to …?’. To be judged a success you need to be able either to answer yes to such questions or to describe why the question is invalid for the engagement you are undertaking.

There are several challenges when it comes to collecting data, and the first is to know what data to collect. To decide that, you must have a clear understanding of the client’s issue and the scope of the engagement. If you do not, most data collection is a waste of time. Assuming you do, the fundamental factor in determining which data to collect is to decide whether you will base your data collection on a predetermined hypothesis or set of hypotheses, or if you will be more unconstrained in your thinking. It is common in consulting to start by generating a hypothesis about a client’s situation and then to seek data which either proves or disproves the hypothesis. Many strategy consultants use this approach.

The advantage of starting without any predefined hypotheses is that you may review a wider range of data sources and you will not be limited by preconceived ideas. The disadvantage is that you start an engagement with a completely blank sheet of paper and potentially an unlimited timescale. If you start with a hypothesis about the client’s issue, then you can short-circuit data collection by focusing only on the data required to prove or disprove the hypothesis. An expert will have hypotheses about a client situation and arguably should always be able to define some starting set of hypotheses – if not, what is the expertise? But, at the same time, starting with hypotheses increases the risk that you may miss some unusual aspect of the client’s situation or innovative solution to their problems. By having a preconceived idea of the client’s situation you have limited the scope of your thinking and review.

Whether you choose to work with a set of hypotheses or have a completely open view depends on the nature of the engagement and what your client requires. Both approaches are valid and each has some advantages. If a client wants an expert to tell them what is wrong quickly and based on past experience, then working with hypotheses is best. If the client wants innovative and novel ideas and analysis of the situation, then it is better for the consultant to take a more objective and open-ended approach to data collection. What is important is to decide consciously which approach is best, and to define your engagement process accordingly.

It is helpful to be realistic about how objective you can be. There is always a degree of subjectivity in collecting data. You can never collect every possible piece of data, and the type of data selected and the method of analysis are subjective choices. This is often forgotten and what is presented as an objective review is really objective data selected from a subjective perspective.

The decision on what data to collect must reflect the nature of the client’s issue and the context and culture of the situation. It is often helpful to explore issues and support further analysis by collecting quantitative data, such as financial information, statistics, figures and measurements. But client problems and issues cannot be truly understood without understanding the context. Few problems are totally independent and therefore you have to have some understanding of the interactions with other areas of the client’s organisation. You must also develop an awareness of the client’s culture. Culture may be part of the client’s problem and part of any solution. Culture will determine the relative importance of issues and the acceptability of solutions. Context and culture cannot be understood purely by quantitative data. What this means is that it is usually necessary to collect both qualitative and quantitative data. Relying only on one or the other will bias the picture you develop of the client, and may also affect how your recommendations are accepted. For example, using purely qualitative data for people with a numerical bias may not result in client acceptance of the findings. Conversely, using purely quantitative data for people with a creative mindset may not be acceptable to them. Most clients have some biases towards qualitative and quantitative data, but also most engagements have a variety of stakeholders with different biases.

We are drawn to quantitative data because it can be manipulated and seems ‘absolute’. In reality, even the most quantitative of consulting data contains subjective estimates and subjective choices are made as to what is relevant and what is not. We are drawn to qualitative data because it gives us a deeper feeling for the situation, and is more difficult to argue with. However, you will never be certain if you have collected a representative sample of qualitative data, and combining different pieces of qualitative data is always to some degree arbitrary. Whatever balance of qualitative and quantitative data you have, finding a sufficient amount of quality data – statistically relevant, found by a quality process, from appropriate reliable sources, etc. – is a key factor in determining the value of the engagement outcome.

Collecting data can throw up a host of unpredicted challenges. The expected data may not exist. It may be that what is ideally required is a historic set of data, but nothing is available. In such situations there needs to be a constructive dialogue with the client. Do you wait until the data is available, does the consultant estimate based on other similar situations, or does the client use gut feeling? Although it is never perfect, estimating and gut feeling are sometimes as good as it gets. Creating completely new data takes time. Problems with data collection is a key reason why you need some level of flexibility in your engagement plan. It is only once the engagement starts that you will really understand what data is and is not available from the client, and if you have committed a very tight timeline to a client with no understanding of the available data then you are taking a significant risk.

There are many sources and approaches to collecting data on a consulting engagement, and often it is necessary to combine data from multiple sources. Sources include:

Some sources of data require specialist skills to undertake (e.g. focus groups), but generally all consultants must be able to construct and ask pertinent and appropriately phrased questions, and understand the responses given. (This is discussed in more detail in Chapter 11.) An understanding of basic data analysis techniques, elementary statistics and at least a basic use of tools like spreadsheets is usually essential.

Unless you have a well-established relationship, clients are rarely 100 per cent open with you, and some client staff will deliberately withhold information. This is human nature. Usually you do not want to know everything; nor does the client want you to. The problem with a lack of openness is that you may develop a false picture of issues and factors like resistance and drivers of change. The lack of openness is more common with qualitative data. However, occasionally you may be given wrong or more usually out-of-date or incomplete quantitative data. Hence, in deciding what data to collect and sources to use, it is sensible to do sufficient data collection to enable you to verify data from several sources and to spot inconsistencies and omissions. Additionally, when you draw conclusions you must always caveat them with the point that they are based on the data that was made available to you.

When you find relevant data, make sure you understand what it really is, and how it has been developed. Names for data sources can be misleading, and well-presented data may appear artificially credible and powerful. If it has been derived from a suspect source or from a small sample size, whilst it may appear valid it will be presenting you with incomplete or inaccurate conclusions.

Data collected by consultants is not just used to draw conclusions, but may also be part of the measurement of the success or failure of an engagement. If you are expecting to deliver a specific and measured outcome to a client, then measurement must start at the beginning and provide a baseline. If you want to measure an improvement, the improvement activity cannot start until measurement is in place. In reality, managers who identify improvements will often not wait for measurement mechanisms to be put in place before starting implementation. This is understandable, but it will make your ability to prove an improvement difficult if not impossible.

Before you decide what data to collect, remember that there is a cost to data collection. Although it is a gross simplification, typically more and better data will take more time and resources to collect. Sometimes clients are willing to pay for the best possible data collection. Often they are not, and sometimes they do not have the time to wait for full data collection. This must be discussed up front and expectations set as to what is and is not possible, and clients should understand the implications.

There is a balance to be found, and more data is not always better. More data can be a hindrance as well as a help. Driving for more and more data will slow the engagement down. A stakeholder who objects to your work can easily undermine it by challenging data sources. It is very easy for a negative stakeholder to continually point out people you have not spoken to or data sources you have not utilised. If you think this is a risk to your engagement, you need to have a clear argument for what is a reasonable and sufficient sample of data, and why you do not need to search continually for more.

Occasionally, consultants themselves can cut corners with data collection and base their findings and ideas on generic principles and limited samples. This is always risky and usually suboptimal for the client. As an expert you should understand what is likely to be happening and what the probable solutions are to any client situation with limited information. But you must avoid the trap of thinking that every client is the same. What is a relevant and significant sample of data in a particular situation depends on the context. One data point is never a relevant sample, and generic information with no understanding of the client’s context and culture is never a basis for value-added consulting.

Having collected sufficient data the consultant can analyse it and consider what the most relevant findings and recommendations are. This is where a consultant’s specialist expertise is directly applied by converting a confusing mass of data into pertinent findings and recommendations. Before analysing the data and producing helpful findings, it is important to be clear about what a client requires, how a consultant adds value, and also to understand the sorts of consultant pronouncements a client is not looking for. This section starts by reflecting on what is of value to clients and then provides some essential tips on findings and recommendations.

How the consultant adds value depends on the client’s needs, and for each of the statements I am about to make there is probably a client who wants something different. However, typically value comes from explaining issues and identifying solutions. A client wants a concise and easily understandable response to their request for help. They are not looking to you to show how complex the situation is, or how thoroughly you have analysed it with an immense and unintelligible list of points. The client already knows it is complex. The client is looking for clarity, innovation and a different answer than they would have come up with themselves. The client may want to reduce risk. You do not help them by identifying each and every possible risk, but by clearly specifying the largest and most probable risks. An engagement needs to be sufficiently wide ranging, but clarity, coherence and usefulness are of far greater value than absolute comprehensiveness.

Conversely, what is the client not looking for? Typically, the client is not looking for the consultant to ‘borrow his watch to tell him the time’. Clients can read their own watches. They may want a consultant to confirm something they already suspect or believe, but that is not the same thing. Clients do not want consultants to rephrase their problems, by analysing what they know to be wrong and telling them this in different words. This is the doctor’s trick of giving you a name for a disease which is essentially just different words for what you have said – or sometimes exactly what you said, but just in Latin. Clients may want you to analyse their problems and define them better or prioritise them, but that is not simply rephrasing them.

Clients are looking for meaningful analysis and recommendations. They are not looking for simplistic views resulting in inappropriate or incomplete advice. If an issue interacts with another issue in the business, you must reflect on the dynamic interplay, and not treat an issue as a stand-alone problem, as the resulting stand-alone solution will not work. Clients are not usually looking for sticking plasters or symptomatic cures for their problems, but want final long-term resolution of problems. Clients are not looking for unbalanced criticism – though of course if they are doing the wrong things you must tell them, but in a constructive way. When you criticise a manager, reflect on the degree of management experience you have. Clients are looking for advice that is helpful and usable in their situation, not ideas that are only applicable in some theoretically perfect organisation.

Clients do not want to hear that the only problem is the organisational culture. A consultant cannot alter the culture, and clients can only do so over a long period of time. Although culture is often a contributory factor to issues, continuous talk of the need for a change in culture is usually lazy consulting. Also, you need to be aware of your own cultural biases. How are they influencing what you see and your solution? (One way to challenge yourself is to ask: ‘If this is such a terrible organisational culture, how come this is a successful business. How many successful businesses have I set up and run?’) You should identify and challenge undesirable elements of organisational culture, but be aware of your own preconditions and assumptions, and avoid simplistic analyses.

Similarly, if a client is going to solve a problem there is little point in only identifying a list of external environmental factors that contribute to the problem, which the client cannot alter. A client must understand the constraints imposed by the environment they operate in. However, a consultant must identify the things a client can change and rectify, not just give a list of reasons for why things are the way that they are and an excuse for the client to do nothing.

Most client value from a consulting engagement is developed in the consider step. It is when findings are made and recommendations are developed. Whilst a consultant must remain independent from the client, there is no point in attempting to point out findings and make recommendations, no matter how wonderful and insightful, that do not add value to your current client at the point in time at which they are being made. Before you undertake any analysis, bear in mind what is and is not useful to the client.

How you analyse data will depend on the data collected and your specialist skill or service lines. If you are a strategist you may have collected information on market drivers, competitive situation and customer trends. If you are an operational consultant you may have gathered information on operational performance, resourcing levels and budgets. If you are an implementation consultant you may have sought out information on readiness to change, resistance to change and project priorities.

One tip in analysing the data you have collected is not to jump to findings and solutions too early. You must respect the client’s need for urgency, but you must also avoid missing out on understanding the problem. Try to avoid, or at least limit, your preconceptions. This is challenging because being an expert means you will have a whole set of opinions which shape your views. The answer must be to balance speed, expertise and previous knowledge with openness to consider the unique characteristics of the situation.

To solve a problem in consulting we typically collect data and then look for patterns in it. An important question is whether the pattern we find is valid. In other words, is there enough data to support the conclusion? A bigger issue is that there is often more than one pattern in any set of data. Whenever you find a pattern, judge whether you have found the right pattern or if there are other ones.

Look at the simple diagram (derived from Chappell, see page 279) in Figure 6.3. Everyone may interpret such a diagram in a different way. For example, is it: a 4 × 5 grid of dots; a rectangle of six dots surrounded by a rectangle of 14 dots; two horizontal rectangles of 10 dots; three rows or four columns between dots; or some combination of these?

Figure 6.3 A simple diagram

This diagram does not represent a business problem, but the point made is still valid. The data collected on a consulting engagement will be far more complex than this and throw up a whole variety of possible patterns. If you start to see a trend in the data early on, by all means be excited by a possibly important finding, but also ask yourself: ‘Is there any other way the data could be interpreted?’

Data, subsequent analysis and findings may initially provide a very complicated picture of a business. Don’t be surprised if the problems in business are complex. The number of people involved and the variety of interacting processes and systems often make this often inevitable. One reason clients are willing to pay for good consultants is to gain clarity through this complexity. Often it is the symptoms of problems that are much more complicated than the causes. The visible manifestation of a problem is highly complex, and each symptom may seem unresolvable in a short space of time, but the root cause may be comparatively straightforward. For example, a poorly designed commission system in a client’s sales department will result in a huge number of undesirable sales with massive knock-on effects across the business. All sorts of problems can be found in a business with a poor sales commission system, such as undesirable customers, high complaints, high customer churn, low profitability, staff turnover and poor staff morale. This can seem like too complex a set of problems to solve in one go, but these are not the root cause, they are only symptoms. The root cause is much simpler: the way a client determines bonuses for sales staff. Find a root cause like this, which is the source of many client problems, and you are on track to rapidly adding huge value to the client.

When analysing a client’s situation, remember that few problems are purely technical. If you just try to understand and solve the technical aspects you will not come up with a complete solution. Human aspects play an important part in most businesses. The way staff are motivated, levels of morale, performance management approaches and so on usually play as significant a role as technical issues.

When reviewing an organisation’s capabilities in any area, focus on strengths as well as the weaknesses. This is not a sop to the client, to help in balancing the good with the bad, but because it is as least as powerful and valuable to build on the strengths as to overcome weaknesses. It is often far more effective for an organisation to try and build on its strengths than to expend huge effort in trying to improve in areas in which it will never excel.

Most problems are understood by a process of analysis and decomposition. This can be powerful, but there must be a synthesis in the end as different parts of the problem interact. Unfortunately, not all problems can be understood by decomposition. Some problems are dynamic and have many interacting contributory causes. Unless you understand the interaction between causes you will never solve this type of problem. In these situations, the synthesis is more important than the decomposition. System dynamics offers a way to look at such interacting problems, and using system dynamics can add powerful insights to clients (see the reference to Senge on page 280).

A common reason to involve a consultant is to help a client make a decision. In making a decision you help a client to move forward, but all decisions have implications. In making one decision the client often closes off other options. Therefore you need to be sure you have reviewed the right range of options with nothing missed and without the scope being artificially constrained. The client should understand the costs and implications of each option being presented. Finally, a consultant should try to understand the value of optionality to a client. Every decision to some extent constrains future options. Clients cannot predict the future. Therefore, what is often of significant value to a client is not simply making the decision that is of the highest value at this point in time, but the choice that still leaves options open in future and hence has the greatest value over time.

Whatever findings and recommendations are made in the consider step, before thinking about presenting them to a client, perform a commonsense check on any conclusions. It is easy in the excitement, pressure and intensity of a consulting engagement to come up with harebrained ideas. The best consulting ideas meet three criteria: they are innovative, implementable and acceptable to the client. Ideas that fail on any of these three criteria are worthless to a client. Before thinking about handing materials over to a client, step back from your work and consider whether it meets these three criteria.

The create step is concerned with converting findings, recommendations or other outputs into a deliverable format that can be utilised by the client. There are many possible formats, although consultants and businesses have a tendency to focus on three: text documents, presentations and workshops, or some combination of all of these. This section is focused on the creation of client deliverables. Chapter 11 builds on this, by reviewing the language of consulting. If your engagement result is a client outcome, Chapter 8 relates to delivering and sustaining client change.

The consider step was concerned with ensuring that the contents of consulting thinking resulting from an engagement are to the quality level required. In the create step the consultant ensures findings and recommendations are converted into a format which is credible to and usable by the client. The importance of this step should not be underestimated. Great content can be undermined in a client’s eyes by poor presentational format. Conversely, weaker content’s credibility can be enhanced by high-quality presentation.

It is only when it comes to creating deliverables that you find out if the findings and recommendations from the consider step are complete and coherent. A set of findings can seem powerful and important in your mind, but weaker or even incoherent when written down on a piece of paper. Yet in the end this is what you must be able to do. It is one reason why it is worthwhile starting to draft deliverables as early as possible in an engagement. This is relevant even if you will only present verbally. For verbal client feedback, think of the line of discussion you will use – if it is not coherent then you cannot create the required deliverable. Early drafts of deliverables focus the consulting team on the result they are trying to achieve, and also ensure you do not reach the end of the engagement with a set of incoherent or incomprehensible findings and recommendations.

What makes a deliverable usable by a client depends on the client’s biases. Some clients love the dynamic interplay of verbal feedback in a workshop, others clients prefer to reflect quietly over a written report they can read several times and think through its implications. One client will favour text, another diagrams and yet others will like figures and numerical analysis. Although different types of consulting outputs are naturally more aligned to certain presentational formats, it is very helpful to understand client biases and learning styles before finalising deliverable formats. The deliverable is primarily to help them, not to show off your skills or knowledge. To achieve this, your engagement plan should be clear about when deliverables will be presented, and you should be clear about who they will be handed over to.

In developing a deliverable the consultant needs to select the media format (written word, spoken word, presentation, etc.), the structure of the deliverable, the type of language used, the formatting within documents, and the balance of factors like diagrams versus text. The language used needs to be appropriate to the subject matter, but consulting jargon should be avoided. The only jargon acceptable is the client’s jargon (see Chapter 11). In general terms the consultant is seeking to create deliverables that are powerfully persuasive, clear and engaging to read or use by the client.

A minor issue, but one which can cause some tension between client and consultant if badly handled, relates to branding on deliverables. Most major consultancies will brand all their reports and presentations with their own company brands. Many clients do not mind how a document is branded and therefore it is a useful way to ensure your consultancy brand is exposed within a client organisation. A few clients find this unacceptable, especially if the work is going to be presented to senior sponsors or even external stakeholders by the client. When clients are sensitive to branding on documents, it is rarely worth annoying or disappointing them by insisting on your branding against their desires.

Branding can be as simple as the use of house style for reports and presentations. Without seeing the actual brand or the content, I can identify the source of certain consulting reports just by their look, colour and format. Some consultancies have very specific formats for all their documents. If you work for one of these firms then you must conform to their corporate standards. My only advice in this situation is to try to avoid impairing the quality of client deliverables by the need to force adherence to a predefined format. The format should always be secondary to the client’s usability of documents.

Deliverables should be marked in accordance with the terms of the proposal and contract with regard to ownership of any intellectual property or copyright, i.e. the documents should be appropriately marked ©abc consulting or ©xyz corporation. If you are going to copyright a report in your consultancy’s favour, this fact should not come as a surprise to a client. Many clients do not care, but some occasionally respond very negatively to the idea that they do not own the copyright for a piece of work they co-developed with a consultancy and for which they paid. Have this debate early on rather than leaving it as a possible argument at the end of the engagement. (See Chapter 10 on ethics.)

Deliverables need to be checked and quality assured (QA) before handing over to clients. At the very least, read through all documents carefully. Mistakes and omissions in documents look unprofessional, reduce credibility and may expose you to risk. The large consultancies often have complex and well-defined QA processes which need to be built into your engagement plan as they can take extensive time. A QA process may require you to spend time with senior consulting managers with very busy diaries. If you are exposed to such a process, do not be surprised if you are asked to make significant changes to the deliverables. After all, the purpose of a QA process is to improve deliverables by asking for changes in them. If you do not want this to become a major problem then try to involve senior consulting managers responsible for QA as early as possible in the engagement. QA processes may look at completeness and relevance of deliverables, but they will also review the risk that recommendations may expose a consultancy to.

Often it is necessary to iterate between this and the next step several times until a client is fully satisfied with the engagement deliverables.

Clients are counselled and consulted not only at the end of the engagement, but throughout it. A client and client’s staff should learn from a consultant across the engagement. This may be from small items of advice, by facilitating workshops, formal training and skills transfer activities, or simply by observing how the consultant works. However, all engagements reach a logical endpoint, when a client must be told the results of the work, counselled on their feelings and responses to this work and consulted on what to do next. Whereas the create step develops deliverables, the counsel and consult step is about presenting and discussing them with clients. This section should be read in conjunction with Chapter 8 on understanding and overcoming resistance.

How you discuss your findings and recommendations is as important to client acceptance as what your findings and recommendations are. Findings and recommendations must be presented with clarity, confidence and assertiveness. Consultants must appear non-judgemental, non-emotional and to the point.

In presenting results you are looking for client acceptance, but of course may have to deal with a level of rejection of your results. You must have sufficient time in your engagement to identify and overcome any client resistance. Such rejection may relate to a client’s emotional or logical response to your results. It may relate to the content of your deliverables, but sometimes it can be triggered by format or how you present. Try to separate these different types of response, as they must be resolved in different ways.

Generally, at the end of an engagement you must present two different things: findings and recommendations. You must understand that these are quite different, and will each generate different levels of understanding, interest and resistance. Make clear which you are presenting when. Start by advising or presenting findings and gaining acceptance to them. Normally, the recommendations will follow on logically and there will be less reason to argue against them. If you mix up findings and recommendations you will tend to confuse the client and this can increase resistance.

Many consultants have never worked outside consulting and therefore understanding what works and what does not, and what is appropriate in any situation, is theoretical or comes from observation rather than direct experience. Hence you must not confuse resistance with the fact that you may actually have drawn the wrong conclusions, or even if you are right it may not work in a specific client organisation. (See Chapter 8 for a detailed discussion on resistance.) The challenge for a consultant is to balance consistency and assertiveness in holding on to results that you believe in and can justify, whilst also listening to the client and being responsive to valid criticism and suggestions.

As part of an engagement a consultant researches a wide range of data to prove hypotheses or suggest alternatives. Although you must be able to justify your findings, the point of feedback is to provide clarity to the client. Resist the temptation to report everything. Less is more powerful. Differentiate between telling the client everything and telling them about the most important or highest priority issues. A consultant provides focus and not unfiltered masses of information. You can always write the details in an appendix. Anyone can find 1000 problems in a large business. Few people have the capability to identify the single most important issue. Remember the lesson in the consultants’ dialogue: ‘Why did you write a 100-page report? ‘Because I did not have time to write a one-page one.’ A synthesis that enables a client to understand a problem truly, rather than get lost in the trees, is significantly more valuable to them.

Often the most useful feedback to clients is confrontational, but confrontational does not mean argumentative. There are ways to present difficult messages and ways to avoid them. Try to separate the confrontational content of your findings from your role as a consultant. Do not shy away from radical ideas, since these are often the most valuable part of consulting. In the end you must present what you think is right, which may not be what the client wants to hear. However, if the confrontational or radical aspects of your results are a relatively minor component of the overall deliverable, separate them from your main findings so any argument about these radical ideas does not spoil the main bulk of your findings.

The outcome from counselling and consulting is the client’s understanding of findings and recommendations, but it should not end there. It must lead to actions. If the client takes no action as a result of your work, then you have failed to add any value. This primarily relates to what the client does next, but it relates also to what you do next with the client.

The deliver stage must start by looking ahead and planning what you will do, but also include expecting and being flexible to needs to modify the plan. As you progress through delivery always think from the client’s perspective. Is what you are discovering innovative, implementable and acceptable to the client? An engagement needs to be sufficiently wide ranging, but clarity, coherence and usefulness are of far greater value than absolute comprehensiveness. The best consulting ideas meet three criteria: they are innovative, implementable and acceptable to the client.

At the end of the engagement you will produce deliverables or achieve a client outcome. You need to be absolutely clear about whether your client is expecting deliverables or an outcome. Any deliverables must be usable by and credible to the client. Any outcome must be in the form of a beneficial change to the client.

As a final tip, check your engagement plan and proposal regularly. It is easy to gradually veer away from it, which is not a problem if agreed with the client as the engagement progresses. But you don’t want to diverge away from the original concept and at the end be surprised when the client checks off what you have done against the proposal.

Finally, the deliver phase is summarised in Figure 6.4.

Figure 6.4 The deliver stage