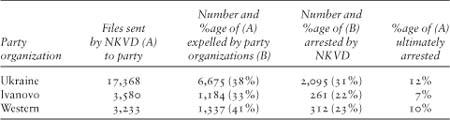

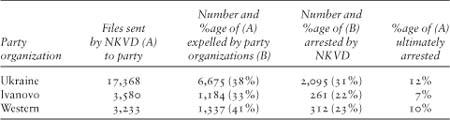

Table 2

Party Expulsions and Police Arrests, 1935

Sources: RGASPI, f. 17, op. 120, d. 184, ll. 63–66; f. 17, op. 120, d. 183, ll. 60–65, 92.

To execute 60 people for one Kirov means that Soviet power is showing weakness by relying on terror to put down the growing discontent.—Komsomol member Ryabova, 1935

The main reason given for the commutation of sentence from death by shooting to ten years’ imprisonment was the argument that this case did not involve a fully constituted counterrevolutionary group…. Do these people really need the fact of a perpetrated crime in order to convict such an obvious terrorist?!

—M. F. Shkiriatov, 1935

NINETEEN THIRTY-FIVE BEGAN IN 1934. On 1 December 1934, the Politburo member, Leningrad party secretary, and Stalin intimate Sergei Kirov was shot in the corridor outside his office in the Smolny building. Over the next four years, the Stalinist leadership used the assassination as evidence of a widespread conspiracy against the Soviet state and its leaders and as a pretext for the Great Terror of the 1930s. Because millions of people were arrested, imprisoned, or shot in the aftermath of the assassination, and because it provided a key justification for Stalinist terror, the crime has rightly been called “the key moment which determined the development of the Soviet system.”1

The assassin, one Leonid Nikolaev, was apprehended at the scene and along with several others was executed in short order. Three days after the killing, the Politburo approved an emergency decree whereby persons accused of “terrorism” could be convicted in an abbreviated procedure, denied the right of appeal, and summarily shot. This decree became the “legal” basis for thousands of summary executions over the next four years. Moreover, complicity in organizing the Kirov murder was attached to almost every high-level accusation made against Old Bolsheviks in the three famous Moscow show trials and many other proceedings.

Stalin used the Kirov assassination as a justification for persecution of his enemies. In fact, most historians believe that he organized the assassination for this very purpose. The question is of more than antiquarian interest for two reasons. First, if Stalin was involved, it would be possible to argue convincingly that he had a long-range plan to launch a terror of the elite and, indeed, of the entire Soviet Union. If, on the other hand, the assassination was not his work, the subsequent terror might appear to be less planned, and explanations of it would have to be sought outside the framework of a grand plan. Debates about Stalin’s possible involvement in procuring the Kirov murder have been fierce but inconclusive because of the lack of official documentation.

In the 1930s various writers cast doubt on the official Stalinist story of an assassin working at the behest of an anti-Soviet criminal conspiracy. Leon Trotsky (“The Kirov Assassination,” 1935) theorized that the killing may have been the accidental result of an operation by the secret police to stage an attempted assassination. Boris Nicolaevsky (The Letter of an Old Bolshevik, 1936) wrote that Kirov’s killing was related to power struggles within the Politburo, with hard-liners standing to gain from the removal of Kirov’s “liberal” influence with Stalin.

Beginning in the 1950s memoirs from some Soviet defectors began to suggest that Stalin may have arranged the crime in order to provide a justification for terror or to eliminate Kirov as a rival. Then, in his speeches to party congresses in 1956 and 1961, Nikita Khrushchev hinted that indeed “much remained to be explained” about the assassination (although he stopped short of actually accusing Stalin).

Working from the memoir literature, Western historians began to piece together the known events surrounding the assassination and its aftermath, and elaborated a compelling case for Stalin’s involvement. In addition to creating a pretext for terror, Stalin’s motives are said to include removing a popular rival and neutralizing a liberal, conciliatory voice on the Politburo that had opposed the Stalinists’ hard-line policies. Kirov was said to be the choice of a secret group of high party officials who, in 1934, cast about for a possible replacement for Stalin. It is believed that this group encouraged a large number of delegates to the 17th Party Congress in 1934 either to abstain or to vote against Stalin’s candidacy to the Central Committee. It is said that Kaganovich personally destroyed anti-Stalin ballots. In this view, Stalin knew about the attempt and decided to remove the alternative candidate and, eventually, all the officials behind the plan.

The strange incompetence of the Leningrad police in failing to prevent the assassination, coupled with possible connections between them and the assassin—it seems that they had previously detained him for questioning—suggested complicity of security officers in the murder. The fact that they received light punishments after the killing also pointed to Stalin’s complicity, and their subsequent executions (along with almost everyone connected to Kirov or to the investigation of his murder) suggested a strategy of removing all witnesses. It seemed possible that Stalin, working through secret police channels, had procured the assassination of Kirov.2

In the 1980s the Politburo launched a new official investigation into the assassination. Assembling an interagency team from the Communist Party, KGB, and other bodies, this committee reexamined the evidence. But as with all previous investigations, the commission failed to produce a report. Their efforts dissolved into mutual recriminations among the members that leaked into the press, as some pressed for a conclusion implicating Stalin while other members argued that the evidence pointed the other way.3 Proceeding from the mainstream Western theories, historians associated with the official rehabilitation effort supported the idea that Stalin was involved. The official party journal in the Gorbachev years promised its readers a full historical account but never produced one. Instead, its coverage of other cases in the Stalin period obliquely suggested Stalin’s involvement in the killing.4

As early as 1973 some historians raised doubts about the prevailing view and made the first sustained Western case against Stalin’s involvement.5Beginning in the 1980s other Western and Soviet historians also questioned the theory of Stalin’s complicity, the origins of the story, and Stalin’s motive and opportunity, as well as the circumstances surrounding the event. They noted that the sources for the theory derived originally from memoirists whose information was second- and thirdhand and who were in all cases far removed from the event. During the Cold War, a flood of Soviet defectors had generated a huge and sensational literature that largely repeated and echoed itself while providing few verifiable facts, and that sometimes seemed primarily designed to enhance the status and importance of the author. These historians also noted that despite at least two official Soviet investigations and the high-level political advantages of accusing Stalin in the Khrushchev years, none of the investigations by even the most anti-Stalin Soviet administrations had accused Stalin of the crime, even though he was directly accused of murdering many equally famous politicians.6

Historians also raised questions about Kirov’s supposed liberalism and resistance to Stalin.7 The evidence for an anti-Stalin group in the leadership that backed Kirov seems quite weak and based on hearsay that was often contradicted by other firsthand accounts.8 In this view, the evidence seems to suggest that Kirov was nothing if not a staunch Stalinist who did his share of persecuting Stalin’s enemies. Similarly, the most recent (Gorbachev-era) official investigation into the supposed anti-Stalin votes at the 17th Party Congress cast doubt on this story, finding that many witnesses reported the matter differently and that it was not possible to verify the story on the basis of personal testimonies or archival evidence.9

The question of Leningrad police complicity also seems murky. Recent evidence discounts the alleged connections between police and the assassin. The NKVD official who supposedly directed the assassin was not even in the city during the months he was supposed to have groomed the killer.10 While it is true that most Leningrad police officials and party leaders were executed in the terror subsequent to the assassination, so were hundreds of thousands of others, and there is no compelling reason to believe that they were killed “to cover the tracks” of the Kirov assassination, as Khrushchev put it. Moreover, they were left alive (and in some cases at liberty) and free to talk for three years following the crime. It has seemed to some unlikely that Stalin would have taken such a chance for so long with pawns used to arrange the killing.

Shortly after the assassination, N. I. Yezhov (representing the party) and Ya. Agranov (representing the NKVD) took charge of the investigation in Leningrad. Yezhov’s archive shows that they pressed assassin Nikolaev hard on any possible connections he may have had with the NKVD and turned up nothing. More than two thousand NKVD workers in Leningrad were interrogated or investigated by Yezhov’s team; three hundred were fired or transferred to other work for negligence. Yezhov reported to Stalin that the men of the Leningrad NKVD were incompetent, careless, and incapable of operating intelligence networks that could have prevented the assassination.11

The head of the secret police in 1934, Genrikh Yagoda (through whom Stalin is said to have worked to kill Kirov), was produced in open court and in front of the world press before his execution in 1938. Knowing that he was to be shot in any event, he could have brought Stalin’s entire house of cards down with a single remark about the Kirov killing. Again, giving a coconspirator this opportunity would appear to have been an unacceptable risk for a complicit Stalin.

Finally, in analyzing the regime’s reaction immediately after the crime, it has seemed to some historians that the events surrounding the crime suggest more surprise than premeditated planning. The Stalinists seemed unprepared for the assassination and panicked by it. Indeed, it took them more than eighteen months to frame their supposed targets—members of the anti-Stalin Old Bolshevik opposition—for the killing.12 Everyone agrees that Stalin made tremendous use of the assassination for his own purposes; it eventually enabled him to make cases against his political enemies, to settle old scores, and to launch a generalized purge. But although there is consensus on his actions after the assassination, there remains great disagreement about his involvement in arranging the crime itself.

Today many Russian scholars are less sure than they once were about Stalin’s involvement. The leading scholars on opposition to Stalin in the 1930s now make no judgment on the matter, and the memoirs of V. M. Molotov (perhaps unsurprisingly) observe that Kirov was never a challenger to Stalin’s position.13 The most recent scholarly work on the Kirov assassination from a Russian scholar, based on Leningrad party and police archives, concludes that Stalin had nothing to do with the killing.14 Similarly, a recent comprehensive study by an American scholar concludes that Stalin was not involved in the assassination.15

Although the instigation of the murder is still unclear, the aftermath and results are not. Stalin used the killing for political purposes. After some initial confusion, the regime blamed the assassination (albeit indirectly) on the former oppositionists of Leningrad led by G. E. Zinoviev.16 Deputy commissar of the secret police Agranov was brought in to supervise a special investigation of the crime to be aimed at Zinoviev and his associate Lev Kamenev.17 The assassin and several former associates of Zinoviev were quickly tried and shot, and in mid-December Zinoviev and Kamenev were arrested. But after one month of questioning, Agranov reported that he was not able to prove that they had been directly involved in the assassination.18 So in the middle of January 1935 they were tried and convicted only for “moral complicity” in the crime. That is, their opposition had created a climate in which others were incited to violence. Zinoviev was sentenced to ten years in prison, Kamenev to five.

Repression also intensified beyond the circle of party members and oppositionists. In the immediate aftermath of the killing, the regime’s reaction was locally savage but spasmodic and unfocused. As they had done in the Civil War, the police immediately executed groups of innocent “hostages” with no connection to the crime. Several dozen opponents, labeled as “whites” and already languishing in prison, were summarily executed in cities around the Soviet Union.19 By February 1935 Yezhov wrote to Stalin that he had rounded up about one thousand former Leningrad oppositionists. Three hundred of these had been arrested, while the remainder were exiled from the city. Yezhov’s archive shows that in this period he put together elaborate card files on the Leningrad oppositionists and kept them under surveillance in their exile locations. More than eleven thousand persons in Leningrad, described as “former people” (nobles, pre-Revolutionary industrialists, and others) were evicted from the city and forced to move elsewhere.20 Characteristically, though, this action provoked disagreement in high places, with Stalin once again acting as referee. Yagoda had protested the exiles, arguing that they would generate bad publicity abroad; Stalin, at Yezhov’s recommendation, approved them. A few months later, however, Procurator Vyshinsky protested against the wholesale, careless, and procedurally illegal nature of the deportations, and Stalin sided with him in reopening many of the cases and allowing the deportees to retain many of their electoral and labor rights.21

In his postmortem investigation of the Kirov killing, Yezhov cast doubt on NKVD chief Yagoda’s competence. Although Yezhov turned up no incriminating evidence against the Leningrad NKVD, he made a strong case for incompetence bordering on the criminal: officers had “put aside their weapons and fallen asleep.”22 Yezhov wrote a detailed report to Stalin on 23 January 1935, ostensibly about his overall impressions of the work of the Leningrad police. But he transformed the report (which he reworked through several drafts) into an indictment of the NKVD in general.23 This letter is a crucial landmark in Yezhov’s career because it represents his first open salvo in his campaign against NKVD chief Yagoda, a campaign that he would prosecute relentlessly for the next eighteen months until Stalin gave him Yagoda’s job: “I decided to write this memo in the hope that it might be useful to you in correcting the work of the ChK [secret police] generally…. Deficiencies evidently exist not only in Leningrad but in other places and in particular in the central apparatus of the NKVD…. Judging from what I saw in Leningrad, I must say that these people do not know how to conduct an investigation.”24 According to Bolshevik discursive and social conventions, this was a bold personal attack on Yagoda. It did not take a genius to see that Yezhov’s implication was that Yagoda’s performance had created a situation in which the regime, and the lives of Stalin and other Politburo members, were in danger. In terms of implications and possible consequences, therefore, the matter was serious; Yezhov was throwing down the gauntlet to Yagoda.25 For the time being, however, Stalin kept the balance. He encouraged Yezhov’s inquiries but continued to defend and retain Yagoda.

Unfortunately, documents from the former party archive shed no direct light on high-level involvement in the Kirov assassination. They do, however, clearly support known trends in arrest statistics: the Stalin leadership chose to politicize the crime and to interpret it as a political conspiracy. Shortly after the trial, the Politburo drafted a circular letter to all party organizations about the “lessons” to be drawn from the Kirov assassination. It sought to educate party members about the danger posed by “two-faced” oppositionists who claim to support the party but work against it:

Now that the nest of villainy—the Zinoviev anti-Soviet group—has been completely destroyed and the culprits of this villainy have received their just punishment—the CC believes that the time has come to sum up the events connected with the murder of Comrade kirov, to assess their political significance and to draw the lessons that issue from an analysis of these events.

The villainous murder was committed by the Leningrad group of Zinoviev followers calling themselves the “Leningrad Center” under the leadership of the “Moscow Center” of Zinoviev followers, which, apparently, did not know of the preparations for the murder of Comrade kirov but which surely knew of the terroristic sentiments of the “Leningrad Center” and stirred up these sentiments.26

Although the January 1935 letter turned up the heat on current and former dissidents, it was not a call for terror. The first sentence of the letter claimed that “the nest of villainy—the Zinoviev anti-Soviet group—has been completely destroyed.” By implication, in the view of the letter’s authors, there were no further nests of villains. A party purge did not follow the letter for nearly five months, and then the screening instructions did not mention the Kirov killing. Zinoviev and Kamenev would not be charged with direct organization of the Kirov killing for more than a year and a half, and then on the basis of “new materials” unearthed in 1936. The January 1935 letter identified the “followers of Zinoviev” (but not Zinoviev himself) and other former oppositionists as counterrevolutionary enemies. This political transcript was read out at all party organization and cell meetings. Party leaders at all levels were ordered to conduct “discussions” of the letter to promulgate its conclusions. These discussions also served a ritual purpose. When they went as planned, they were to be forums for rank-and-file party members and citizens to repeat and affirm the proffered political narrative.

The letter invited local party organizations to identify present and former dissidents. The local discussions suggest, though, that there was a shortage of real Zinovievists remaining in party organizations. Accordingly, various marginal and unpopular characters were identified as oppositionists and punished. Sometimes the discussions of the Kirov assassination and the January 1935 letter tended to be routine and ritualistic, reflecting apathy and “weak participation” in the prescribed discourse. Frequently the meetings “unmasked” some unfortunates as “enemies,” but such targets tended to be defenseless marginal types. On other occasions the meetings seem to have been more emotional, either encouraging further investigations or unearthing “anti-Soviet moods.”27

Statistics on overall repression in the months following the Kirov assassination reveal some curious trends. In terms of police arrests, overall repression did not increase in 1935. The number of NKVD arrests in 1935 was lower than it had been even in the previous, calm year of 1934 (see table 1). The secret police made fewer arrests in 1935, in fact, than in any year since 1929. NKVD arrests had been declining steadily every year since 1931, and they would fall even lower in 1936.

But the character of those arrests was changing. Inside the lower aggregate arrest totals, arrests for political reasons were increasing: compared with 1934, there were 10 percent more arrests for “counterrevolutionary” crimes and two and a half times as many arrests for “anti-Soviet agitation” in 1935.28 The proportion of NKVD arrests for nonpolitical offenses fell correspondingly. In other words, while total arrests were down, those arrests that did take place in the wake of the Kirov assassination were increasingly defined as “political.”

In 1935 the NKVD arrested about 193,000 persons on all charges. In previous years, various proportions of those arrested were ultimately convicted, but in 1935 convictions exceeded arrests by more than 74,000 persons. In the months following the Kirov killing, thousands of people already under arrest before the assassination were reconvicted under more political charges. Unfortunately, we have no information on their new sentences, but the statistics we do have do not suggest that their new politicized sentences were necessarily more harsh. In 1935, although the total number of convictions was three times higher than in 1934, the proportion of sentences to prison or labor camp fell from 75 percent to 70 percent; executions as a proportion of all sentences fell from 2.6 percent to 0.4 percent. Less severe types of sentences increased: exile (either to a specific place or as denial of right to live in major cities) from 7.5 percent to 12.5 percent and other (mostly noncustodial) sentences from 14.5 percent to 17.3 percent.

Police repression of the former opposition intensified in the wake of the Kirov assassination. Aside from the January 1935 trial of Zinoviev and Kamenev, there were several less publicized judicial proceedings against former oppositionists in Leningrad, Moscow, and other cities. The trial of the “Leningrad Counterrevolutionary Zinovievist Group of Safarov, Zalutsky, and others” sentenced 77 defendants to camp and exile terms of four to five years.29 Altogether in the two and one half months following the assassination, 843 former Zinovievists were arrested in Leningrad; most were exiled to remote regions and not sentenced to camps.30 As one investigator told a detainee, formal guilt or innocence was not the point: “The proletariat demands the exile of everyone directly or indirectly connected with the opposition.”31

N. I. Yezhov had been a Petrograd worker who joined the Bolsheviks in the summer of 1917. Active as a political organizer and commissar during the Civil War, he worked in several provincial party committees in the 1920s and had a reputation as a solid party worker.32 Perhaps spotted by L. M. Kaganovich, who ran the Organizational-Assignment Department of the Central Committee in the 1920s, Yezhov was brought to Moscow to work in the central party apparatus and by 1930, at Kaganovich’s suggestion, was attending Politburo meetings.33

In the early 1930s he worked in the Central Committee’s Industrial and Cadres (personnel) departments. By 1933 he had become a kind of personnel “checker.” By January of that year he was heading the Central Committee’s personnel assignment department. He played a leading administrative role in the 1933 party screening (chistka) and in a number of other bureaucratic verification operations.34 From early 1934 his rise was meteoric. At the 17th Party Congress in early 1934 he headed the Mandate (credentials) Commission of the Congress and was elected a full member of the Central Committee (skipping over candidate member status altogether), a member of the Orgburo, and Deputy Chairman of the Party Control Commission (KPK).35

By 1934 Yezhov ranked high enough to earn the privilege of traveling abroad for rest cures, funded by hard currency from party coffers. It was common for high-ranking party leaders to go abroad for rest and relaxation in health spas. In 1934 Yezhov went abroad to a spa with a disbursement of twelve hundred rubles in foreign currency. He was apparently so dedicated to his work that the Politburo had to forbid him to return until the end of his rest, forwarding him an additional one thousand gold rubles to complete his rest vacation.36

In early 1935, as part of a series of security checks following the Kirov assassination, the NKVD began investigating the staff of the Kremlin. Arrests began in February, and by early summer 110 employees of the Kremlin service administration (including some of Kamenev’s relatives) were accused in the “Kremlin Affair” of organizing a group to commit “terrorist acts” against the government. Ultimately, two were sentenced to death; the remainder received prison or camp terms of five to ten years.37

A. S. Yenukidze, as secretary of the Central Executive Committee of Soviets, was responsible for administration of and security in the Kremlin. The Kremlin Affair, in which dozens of Kremlin employees were arrested for conspiracy, cast suspicion on Yenukidze’s supervision. The suspicion was compounded by Yenukidze’s softhearted tendency to aid old revolutionaries who had run afoul of Soviet justice. Yezhov made his debut as a visible player in the Central Committee at the June 1935 plenum of the Central Committee, where he delivered the official accusation against Yenukidze.38

The Kremlin Affair of 1935 provided the basis for a further sharpening of the political atmosphere in mid-1935 by casting doubt for the first time on high-ranking party officials who had always sided with Stalin. The scene for this escalation was the June 1935 plenum of the Central Committee, where Yenukidze was accused of aiding and abetting the “terrorists.” Yezhov was the agent for this heightening of tension and made his national political debut at the June plenum as Yenukidze’s accuser and bearer of the latest narrative from on high.

It was a curious text. He began not by criticizing Yenukidze, but rather with a lengthy digression on the crimes of Zinoviev and Kamenev. To this point, they had been accused of only “moral complicity” in the death of Kirov. Now, however, Yezhov for the first time accused them of direct organization of the assassination and introduced the idea that Trotsky was also involved from his base in exile. Despite Yezhov’s claim to the contrary, this was a radical new theory and one that could give no comfort to political dissidents.39

Yezhov’s speech had treated the Yenukidze affair almost as a sidelight, and it is tempting to see the Yenukidze accusation as a pretext for introducing a new prescribed version of the transgressions of Zinoviev, Kamenev, and Trotsky. If this is true, and Yezhov’s speech was a kind of trial balloon (either Yezhov’s or Stalin’s), it was a strange and unsuccessful attempt to recast the prevailing political line on the opposition.

First of all, Stalin did not speak in support of Yezhov’s theory. This in itself was not strange; Stalin often used his henchmen to make his points while remaining silent. But this time, the usual chorus (Kaganovich, Rudzutak, Shkiriatov, and others) did not strongly back Yezhov. Second, despite Yezhov having posited “direct participation by Kamenev and Zinoviev in the organizing of terroristic groups” and having said that “the murder of Comrade Kirov was organized by Zinoviev and Kamenev,” no new charges were brought against them, and it would be more than a year after Yezhov’s speech that these two were brought to trial for the crime. During that period, their names almost never appeared in the press or in party speeches, even though a high-ranking party official had accused them of organizing the assassination of a Politburo member. Finally, Yezhov’s failed new narrative was never published.

Why the strange delay in following up on Yezhov’s thesis? No one spoke in defense of Zinoviev and Kamenev and no one suggested moderation or delay at the plenum, at any subsequent plenum, or in any documents at our disposal. Indeed, it is hard to imagine that the nomenklatura would want to defend them. After all, by identifying these has-beens as the enemy, the new theory suggested that any and all problems could be blamed on their treason, rather than on “bureaucrats” who did not “fulfill decisions.”

There would appear to be two possible explanations for the failure of Yezhov’s initiative against Zinoviev and Kamenev in June 1935. On the one hand, there could have been quiet opposition in the Central Committee that forced Stalin to stay his hand. Or it may well have been Stalin himself who was unsure about what to do with Zinoviev and Kamenev. He might have allowed Yezhov to float his trial balloon, then left him dangling by telling him that it was possible to follow up only if Yezhov could prove the charges. It would take Yezhov a year to get the “proof” by forcing Zinoviev and Kamenev to confess.

Although Yezhov’s wild denunciation of former oppositionists was met with inaction, the members of the Central Committee did discuss the Yenukidze accusation, and the discussion shows the “lessons” party members were to draw. As always, the target of an accusation was expected to perform an apology ritual. Yenukidze, however, refused to play his part:

YENUKIDZE: No one was hired for work in the Kremlin without their security clearance. This applies to all officials without exception.

YAGODA: That’s not true.

YENUKIDZE: Yes, it is.

YAGODA: We gave our security report, but you insisted on hiring. We said not to hire, and you went ahead and hired.

YENUKIDZE: Comrade Yagoda, how can you say that?40

Yenukidze did not fully grasp what was required of him. Like his CC comrades, he recognized the propriety and gravity of the accusation, but he claimed that he was not guilty of anything. He refused to take his medicine and carry out the apology ritual. In his speech he had claimed that his organization was no better or worse than others and had blamed the NKVD and Control Commission officials for vetting the personnel who had been accused. Politically, he was still reading from a different page. His speech was constative, about true and false assertions, when what was required was performative speech that would do work. That work involved becoming a ritualized agent, transforming himself through language in a particular ritual setting into a serviceable “other,” a “lesson” that the Central Committee could use politically.

Genrikh Yagoda, head of the NKVD, had to say something. According to formality and logic, his organization should have discovered the crime and reported on it. Instead, Yezhov, from the party secretariat, had uncovered and reported the “treason,” a fact that already cast doubt on Yagoda’s competence.41 Yenukidze had blamed the NKVD in his remarks. The NKVD was explicitly and implicitly under fire. Yagoda had to speak, and in his own defense had to be tough and uncompromising. He had to be more Catholic than the pope: “I think that by his speech Yenukidze has already placed himself outside the bounds of our Party.

“What he said here, what he brought here to the Plenum of the Central Committee, is the pile of rubbish of a philistine. Everything that Yenukidze has said here is nothing but unadulterated lies.”42

Yagoda proposed the expulsion of Yenukidze from the party, going beyond Yezhov’s recommendation only to remove him from the Central Committee. In his remarks Yagoda had made an interesting point about Yenukidze’s “parallel ‘GPU’” and revealed that as late as 1935, high-ranking members of the nomenklatura had been able to thwart the secret police. In Yagoda’s words, whenever Yenukidze “recognized one of our agents, he immediately banished him.”

It fell to L. M. Kaganovich, as a real insider, to make the main point, to provide the main “lesson” of the Yenukidze affair. Recalling one of the themes of Stalin’s speech to the 17th Party Congress, Kaganovich insisted that everyone—no matter how exalted his rank—must adhere to the master narrative and to the rituals of party discipline: “Our Party is strong by virtue of the fact that it metes out its punishment equally to all members of the Party, both in the upper and lower echelons…. This matter, of course, is important not only as it pertains to Yenukidze but also because we undoubtedly have in our Party people who believe that we can now ‘take it more easily’: In view of our great victory, in view of the fact that our country is moving forward, they can now afford to rest, to take a nap.”43

So for Kaganovich the point was not whether or not the NKVD had missed the boat (although that lesson was lost on no one). The crux of the matter was not even whether or not Yenukidze was formally guilty or not. The point was that no one, not even those who had always been senior Stalinists, was above party discipline. Not even highly placed members of the nomenklatura who ruled their fiefs with an iron hand were immune to control or to the demands of the party. Yenukidze’s duty as a Bolshevik was to discuss how enemies had stolen their way into the apparat, how he had protected dubious people. The party had demanded that Yenukidze help it teach a lesson, and Yenukidze had failed to play his role.

For years, the nomenklatura had demanded that lower-ranking party functionaries play the roles assigned to them: to help provide negative examples and changes in policy by making formal apologies and posing as scapegoats. Members of opposition groups who found themselves on the losing side had been expected to do the same to win readmission to the nomenklatura. What was new in the 1930s was the expectation that the highest-ranking members of the Stalin coalition do the same when duty called. As Kaganovich had said, “Our Party is strong by virtue of the fact that it metes out its punishment equally to all members of the Party, both in the upper and lower echelons.” A. P. Smirnov in 1933 and now Yenukidze in 1935 had failed to understand that.

Kaganovich’s discussion of the decision-making process shows that the inner leadership, including Stalin himself, had difficulty deciding what to do with Yenukidze. Various punishments had been discussed. Yezhov’s personal papers contain three draft decrees on Yenukidze prepared before the meeting. The first proposed only removing him from his Central Executive Committee (TsIK) position and appointing him TsIK secretary in Transcaucasia. By the third draft, because of “new facts coming to light,” the punishment had been escalated to “discussing Yenukidze’s Central Committee membership.” This was the proposal that Yezhov brought to the meeting.

Speaker after speaker denounced Yenukidze’s sins in a ritual display of nomenklatura unity and anger. By joining to isolate Yenukidze, the members of the Central Committee were not only supporting Stalin’s charges (but not, as we shall see, Yezhov’s) but implicitly affirming their individual status as well as their collective right to decide punishment. CC apology rites had a transactional component; the final sanction depended on how well the subject had played his part. In this case, Yenukidze’s declining the prescribed rite infuriated the group. The increasingly angry nature of the discussion at the plenum led to a second motion to expel him from the party altogether. At the end of the plenum, both proposals were put to the vote. Yezhov’s motion to expel him from the CC passed unanimously; another proposal to expel him from the party passed by a simple majority.44

The split vote (itself an extreme rarity in the Central Committee) on the disposition of Yenukidze’s fate was not something the top party leadership wanted to broadcast to the party rank and file. In the version of the plenum minutes printed for distribution in the party, the event was portrayed differently. History was rewritten to make it seem that there had been only one proposal and that the ultimate decision—to expel him from the party—was based on an original Yezhov motion, which he never made. The image of a united leadership had to be maintained with a single text.45

It is of course possible that the second, harsher proposal—to expel Yenukidze from the party—came from Stalin through his representatives. In this case, the strategy would have been to have Yezhov put forward a suggestion for moderate punishment of a key nomenklatura member in order not to alarm the elite, to gauge the reaction, and then to see what developed.

It is more likely, however, that the ad hoc harsher punishment came from the nomenklatura itself in the course of the plenum. In such a case, the nomenklatura was more radical in its punishment than Stalin himself. It could well be that Yenukidze’s refusal to carry out the apology that elite discipline required infuriated the elite in the Central Committee. It may well have been that the elite went into the plenum with a quid pro quo in mind: in return for his formal apology, Yenukidze would be spared a full scapegoating and could remain in the party. His refusal or failure to comply thus led to the harsher punishment.

There is some reason to suspect that in the end Yenukidze was punished rather more harshly than Stalin had originally intended. At the first plausible opportunity, two plenums later in June 1936, Stalin personally proposed that Yenukidze be permitted to rejoin the party. At that time, Stalin explained that this was the earliest moment Yenukidze’s readmission could take place: “Otherwise, it would be like expelling him at one plenum and readmitting him at the next.” Readmitting Yenukidze then was a curious irony. For it was at that plenum that the Politburo announced the upcoming capital trial of Zinoviev and Kamenev for the assassination of Kirov, the theory Yezhov had put forward at the plenum that expelled Yenukidze.

Central Committee members must have taken several lessons from the June 1935 plenum. First, they were introduced to the idea that Zinoviev’s and Kamenev’s guilt might be greater than previously thought. Second, Yezhov was now a visibly important player before the Central Committee: he had brought down the secretary of the Central Executive Committee and stepped forward as the herald of a modified (albeit temporarily unsuccessful) narrative. Third, Yagoda and the NKVD had been discredited. Fourth, and most uncomfortable for them, one of the highest-ranking members of the nomenklatura (and a personal friend of Stalin’s) had violated discipline. For some members of the elite, this action must have been personally disquieting: if Yenukidze could fall, no one was safe. For others, however, the lesson was that the dangers and threats of the new situation had infected even the inner circle of the nomenklatura.

As was so often the case, Stalin remained in the shadows of the plenum. What did he think? What did he want? What, if any, were his plans? The events of the Yenukidze plenum are consistent with a plan to escalate repression and prepare the way for terror. Incriminating Zinoviev and Kamenev (along with Trotsky) in capital crimes clearly raised the stakes in defining enemies and punishments. Similarly, casting a shadow on a serving member of the upper nomenklatura—some speakers like the hysterical Yagoda had practically equated Yenukidze’s guilt with Zinoviev’s— could open the door to persecution of the elite itself in an unfolding terror.

On the other hand, Stalin’s failure to take a position could reflect his own indecision about launching generalized repression. He personally softened many of the sentences that Yagoda proposed for those convicted in the Kremlin case, including commuting some death sentences and ordering the release of several defendants. When in May 1935 Yagoda jumped on Yezhov’s bandwagon against the opposition by arguing that Kamenev was “organizer of an attempt on the life of Comrade Stalin,” Stalin rejected the accusation and reduced Yagoda’s proposed death sentence for Kamenev to ten years in jail.46

Moreover, if these June 1935 events were part of a scheme to move against major oppositionists, it remained stillborn for so long a time that their purported lessons were lost or devalued. Yezhov’s accusations against Zinoviev and Kamenev were not followed up for a year; this was hardly striking while the iron was hot. To insiders skilled at reading the tea leaves of Central Committee plenums, the unitary lesson that Yenukidze’s fall apparently provided was muted by Kaganovich’s admission that the Politburo had had trouble deciding what to do, and was erased by Yenukidze’s clean bill of health at Stalin’s hands in June 1936. No ranking nomenklatura members would be arrested until the end of 1936, more than a year and a half after the Yenukidze plenum.

Finally, Yezhov’s debut in the role of hatchetman against “enemies” was not an unqualified success. Not only was his main “thesis” ignored, but the proposal he put forward on Yenukidze was overruled. Given that everyone must have known that his recommendation on Yenukidze must have been approved by Stalin and the Politburo beforehand, the impression created was that the radical Yezhov had been taken down a peg at the moment of his triumph. No one except the master balancer—Stalin— could have permitted that.

Other documents from June and July 1935 nevertheless suggest a more “vigilant” and repressive atmosphere on the local level. For example, in the Azov–Black Sea Territory, there was a new crackdown against rural opponents. New loyalty checks were to screen officials for dubious pasts, and for good measure, fifteen hundred “kulaks and counterrevolutionaries” were to be deported from the province.47

New central decrees also sought to tighten controls over subversive book collections in libraries (perhaps in light of reports that the Kremlin Affair conspiracy had been centered in the Kremlin Library). A June 1935 decree ordered a list of “Trotskyist-Zinoviev” books to be removed from libraries but warned against “an uncontrolled and ungovernable ‘purge’ of libraries … and damaging of library resources.”48

Increasing ideological and literary controls also extended to the members of the nomenklatura itself. Stalin, having emphasized “political education” and ideology since 1934 (see his speech to the 17th Party Congress) had personally taken control of the Culture and Propaganda Department of the Central Committee in April 1935. His personal interest and control over ideology is reflected in a document in which a ranking member of the nomenklatura was brought up short. No one was to be allowed to alter the public rhetoric about the supreme leader, even in the direction of glorification, without permission.49

Typically, however, even as things swung in the direction of harder and harder policies, there continued to be countervailing texts that suggested softer, legal tactics. Some documents reflect a liberalization of the policy enforced on exiled “enemies.” Such granting of “privileges” was uncharacteristic of either the preceding period or the subsequent terror and represents a kind of isolated text in an otherwise darkening picture. The new rules permitted condemned “enemies” to work in their specialties; all memoir accounts agree that such a possibility was important to detainees. These new regulations also removed the legal stigma from children of the regime’s victims. The central leadership had not yet decided on the completely brutal and severe treatment of its victims that would follow in 1937.50

In mid-June the Central Committee produced a regulation on procedures for conducting arrests. As with all such documents, it sent mixed signals. On the one hand, it seemed to tighten up the requirements for arrest by insisting that all arrests without exception had to be approved by the relevant procurator. On the other hand, though, in spelling out the approvals necessary for detaining persons in various positions, it foresaw the possibility—which could not have been lost on Stalinist officials—that high-ranking persons might in the future be arrested.51

It is also likely that this and similar decrees had another purpose: restriction of the powers of regional party leaders to conduct their own arrests in the provinces without judicial supervision. In Belorussia, for example, party provincial secretaries had sought to control railroad personnel through mass arrests. One Control Commission representative said that “tens, hundreds were arrested by anybody and they sit in jail.” In the Briansk Railroad Line, 75 percent of administrative-technical personnel had been sentenced to some kind of “corrective labor.” In Sverdlovsk and Saratov, Control Commission inspectors sent from Moscow reported that locals had “completely baselessly arrested and convicted people and undertaken mass repressions for minor problems, sometimes for ineffective leadership and in the majority of cases, arrested and convicted workers who merely needed educational work.”52 By insisting on the procurator’s permission in order for an arrest to be made, the Central Committee was taking unlimited arrest powers out of the hands of regional party leaders.

On the other hand, the fall of 1935 also brought a political hardening and a kind of legal nihilism inconsistent with many of 1934’s initiatives that had seemed to augur an era of legality and rule of law. In September 1935 Yezhov gave a secret speech to a closed meeting of party personnel officials from the provinces. Contradicting written party and state texts, he advised party officials sharply to restrict the rights of expelled members to appeal, and not to be restrained by procurators’ insistence on procedural legality. “What guarantee do we have that a crook may not somewhere succeed in slipping through? Besides, for all we know, a certain liberalism may have been shown in respect of individual Party members…. Here our Procuracy has, to some extent, made a mess of things.” He also encouraged his audience to make use of extralegal bodies to convict “dangerous elements” not guilty of a specific chargeable offense. Finally, he chided party organizations and the NKVD for stepping on each other’s toes, referring to “certain officials who have gotten the NKVD involved where it is not needed, who have dumped work on the NKVD that they should have done themselves and who, on the other hand, do not permit the NKVD to concern itself with that which the NKVD should concern itself with.”53

A few weeks later, M. F. Shkiriatov, a hard-line Party Control Commission functionary, wrote to Stalin about the case of one V. A. Gagarina, a “counterrevolutionary” who had been freed upon appeal by the Supreme Court. His description of the case also shows the tendency to override legal procedures, and is a classic statement of Bolshevik voluntarism and expediency at the expense of legality. It also indicates, however, that some judicial officials were willing to follow the letter of the law rather than the Shkiriatov version of political expediency. Such documents show that the “moderate” legalistic documents upholding procuratorial sanction and process, while more and more observed in the breach, did sometimes have an effect.54

Another party membership screening operation, or purge, came in the middle of 1935: the verification (proverka) of party documents. Planned even before the Kirov assassination, this purge was in the tradition of party screenings since 1921 and was designed to rid the party of “ballast”: corrupt bureaucrats, those who had hidden their social origins or political pasts, those with false membership documents.55 The order for the operation (“On Disorders in the Registration, Distribution, and Safekeeping of Party Cards and on Measures for Regulating This Affair”) had characterized the verification as a housekeeping operation to bring some order to the clerical registration of party membership documents. Although the proverka did not specifically call for the expulsion of former oppositionists, it was inevitable that many of them would be targeted in this background check.56

According to a report by Yezhov, who was in charge of the screenings, as of December 1935, 9.1 percent of the party’s members had been expelled in the proverka, and 8.7 percent of those expelled had been arrested; he gave a corresponding figure of 15,218 arrests out of 177,000 expulsions, or a little less than 1 percent of those passing through the verification.57 The level of arrests varied considerably from province to province, and there is strong evidence that relations between party and police were not always smooth. The NKVD generated documents attesting to their close cooperation with party committees.58

Such reports were meant to show unanimity to the middle party leaders. But the hidden transcript was different. In a September 1935 meeting, Yezhov noted that cooperation between party and police organizations was not good. Party organizations had been reluctant to concede a political monitoring role to the NKVD, preferring instead the former system in which the NKVD investigated state crimes not involving members of the party and left political offenses to the party organs.59 The information in table 2 shows, in fact, that party and police organizations worked badly together and frequently disagreed on who was “the enemy.” Yezhov gave the 1935 operation a combative stamp by calling for verifiers in the party organizations to concentrate on expelling ideological enemies of all kinds. “One thing is clear beyond dispute: It seems to me that Trotskyists undoubtedly have a center somewhere in the USSR.” His remarks emphasized the hunt for enemies.

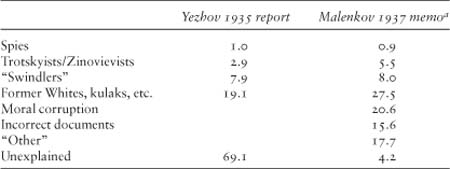

Despite Yezhov’s concentration on Trotskyists and other enemies, the results of the verification, like previous party screenings, struck hardest at rank-and-file party members with irregularities in their documents, many of whom were charged with generally nonideological offenses having to do with malfeasance or “alien” class background. Two reports, one from Yezhov’s 1935 report and another from an internal Central Committee memo written by G. M. Malenkov, are summarized in table 3 and show the categories expelled.

Table 2

Party Expulsions and Police Arrests, 1935

Sources: RGASPI, f. 17, op. 120, d. 184, ll. 63–66; f. 17, op. 120, d. 183, ll. 60–65, 92.

Table 3

Reasons for Expulsion, 1935–36 (%ages of all expelled)

Sources: RTsKhIDNI f. 17, op. 20, d. 177, ll. 20–22; f. 17, op. 120, d. 278, l. 2. aIncludes persons expelled in 1936 after the completion of the chistki.

The conduct of the proverka shows some interesting aspects of the relationship between central and provincial party organizations. Since the late 1920s provincial party leaders had become powerful political actors on a par with feudal barons. They controlled the police, courts, trade unions, agriculture, and industry in their territories. Responsible to Moscow for fulfillment of plans, they ran hierarchical organizations based on patronage and personal power. Stalin had referred to them in 1934 as “feudal princes,” who pigeonholed Moscow’s orders rather than fulfilling them, did their best to conceal the real situation from Moscow, and “thought [Moscow’s] decisions were written for fools, and not for them.”60 Formally, they represented central authority in the provinces, but in reality they ran powerful political machines that dominated economic, political, and social life in their territories.

The instructions locals received had been vague. On the one hand, the document instigating the verification made it out to be a clerical rectification of party files and membership cards, fully consistent with a mass screening of the rank and file (those most likely to have defective or dubious cards). On the other, Yezhov had characterized it as an operation to uncover oppositionist elements, including Trotskyists and Zinovievists.

Because membership in the Trotskyist or Zinovievist organizations implied party membership dating back into the 1920s, “genuine” ex-oppositionists were likely to have worked their way up from the rank and file into leadership positions in local political machines. Yezhov’s call, therefore, was implicitly a demand for local members of the nomenklatura to purge their own “families,” doubtless an unpopular idea. The tendency of local elites to deflect the purge downward to the rank and file was almost certainly a response to the need to find enemies somewhere without risking the loss of experienced members of their own machines, even if they had dubious backgrounds. Purge discourse was flexible.

The Central Committee was not satisfied with this result. The frequent interventions from Moscow to stop and restart local verifications, along with subsequent criticism of local administrations, provide evidence of Moscow’s displeasure. Documents also show that central party officials gathered information on how many members of local political machines had been identified and expelled.61 In response, local machines tried to show that they had screened their own people. Here we see further evidence of a rift inside the nomenklatura elite, in this case between Moscow-based party leaders and regional party officials. From Yezhov’s point of view, by entrusting the purge to party organizations themselves (rather than to control commissions or special purge committees, as had previously been the practice), he was giving them the chance to put their own houses in order.62 Instead, they had protected their own and displayed their “vigilance” by expelling large numbers of helpless party members outside the local nomenklaturas.

Regional party committees had begun the proverka in May 1935. The following month, however, many of them were brought up short by the Central Committee, which criticized them for paying only cursory attention to the process and for hastily expelling large numbers of ordinary rank-and-file members (and few leading comrades) from their own machines.63 Following accepted party ritual, the local and provincial committees quickly admitted that the Central Committee was right, confessed their mistakes, and tried to demonstrate their vigilance even against a few members of their own machines. Nevertheless, the overwhelming majority of those expelled remained rank-and-file members with suspicious biographies (“white guards and kulaks”).

Moscow party leaders were concerned that the mass expulsions could create embittered enemies among ex-party members.64 By the end of 1935 Moscow was investigating the numbers of expelled and finding that some party organizations had as many former members as current ones.65 Moscow party officials not only kept an eye on those expelled, they checked into their moods.66 Sometimes these ex-members were characterized as “enemies.” A report from the Azov–Black Sea NKVD had it that “the available facts concerning the attitudes and conduct of persons expelled from the VKP(b), in connection with the verification of Party documents, indicate that a significant number of persons expelled is beginning to manifest counter-revolutionary activity, committing counter-revolutionary attacks against leading Party officials and threatening revenge for being unmasked and expelled from the Party.”67 On other occasions, though, Yezhov and others explicitly noted that the behavior of most ex-members was benign.

The membership screenings not only embittered those expelled. For some committed Communists, the loss of party membership meant not only a loss of privilege and elite status but a crushing psychological blow from which they could not recover. On many fronts at the end of 1935, the number of personal tragedies was increasing. Suicides and suicide notes attracted the attention of the party leadership.68

For the Stalinists in the 1930s, almost everything carried a threatening political content. Even suicide, which might be seen to represent to the Stalinists a welcome self-destruction of opponents, was seen as a dangerous political “blow against the party” by a dishonest person. As Stalin mused in 1936, “A person arrives at suicide because he is afraid that everything will be revealed and he does not want to witness his own public disgrace…. There you have one of the last sharp and easiest means that, before death, leaving this world, one can for the last time spit on the party, betray the party.”69

Indeed, the most “famous” suicide of the 1930s, that of Sergo Ordzhonikidze, posed special problems for the regime. Ordzhonikidze had always been a staunch Stalinist; yet in February 1937 he killed himself. Unlike others, his suicide was never characterized as political betrayal. Rather, the embarrassing political fact of his suicide was hidden by the regime. His death was publicly announced as heart failure, and Nikita Khrushchev, a member of the Politburo, did not learn the truth about Ordzhonikidze’s death for many years.

It was not only suicides of prominent politicians that worried them; the Stalinists feared even the suicides of their opponents. During the 1930s suicides of rank-and-file party members and even ordinary citizens attracted the attention of the top leadership. Even if they involved the most minor party members, such events were routinely investigated by the Special Political Department of the NKVD and found their way into Central Committee files.70

The Kirov assassination had come as a shock to the political life of the Soviet Union from top to bottom. Everyone, from Stalin to the lowest party secretary, had to reorient himself and figure out how to use the new political texts and situations. There was no authoritative decision on the extent of the oppositionists’ guilt or, indeed, on who was an oppositionist or who needed to be expelled from the party. Hard and soft policies continued to coexist, and nobody knew exactly where Stalin stood.