SOCIAL SECURITY REDUCES INEQUALITY—EFFICIENTLY, EFFECTIVELY, AND FAIRLY

Two scholars who served on the staff of President Reagan’s 1982 National Commission on Social Security Reform explain that Social Security does more to reduce income inequality and prevent poverty among the old in the United States than any other program, public or private, while providing crucial protection for orphans and the disabled. And, contrary to widely circulated claims, they show it does not add one dollar to the federal government’s budget deficits and can remain financially sound as long as our government exists.

Generations of Americans built our Social Security system to provide basic and widespread protection against loss of earnings arising from the death, disability, or retirement of working Americans—for themselves, their families, and those who follow. Like the Constitution or other major institutions, it requires modest adjustments from time to time, but its basic structure is sound. It has worked well for seventy-seven years, never failing to meet its obligations, even during the deep recession that followed the near collapse of the economy in 2008. There is no reason it can’t continue to do so as long as the United States is around.

Social Security gives concrete expression to widely held and time-honored American commitments. Grounded in values of shared responsibility and concern for all members of society, it reflects an understanding that, as citizens and human beings, we all share certain risks and vulnerabilities; and we all have a stake in advancing practical mechanisms of self- and mutual support. It is based on the belief that government—which is simply all of us acting collectively—can and should uphold these values by providing practical, dignified, secure, and efficient means to protect Americans and their families against risks they all face.

Social Security runs seamlessly and efficiently—less than 1 percent of its expenditures are for administration.

Social Security provided monthly benefits in 2013 to 57 million Americans:

37 million retired workers

2.3 million spouses of retired workers

3.9 million aged widow(er)s

8.9 million disabled workers

256,000 disabled widow(ers) ages 50 to 66

3.5 million children under age 19

1 million severely disabled dependent adult children

160,000 spouses of disabled workers, and

146,000 spouses of deceased workers caring for dependent children.*

Although Social Security’s benefits are modest, they are extremely important for the vast majority of beneficiaries, especially those with low and moderate incomes. The average benefit is about $15,000 a year for retired workers; about $12,700 a year for survivors of workers; and about $11,700 for disabled workers and their families.

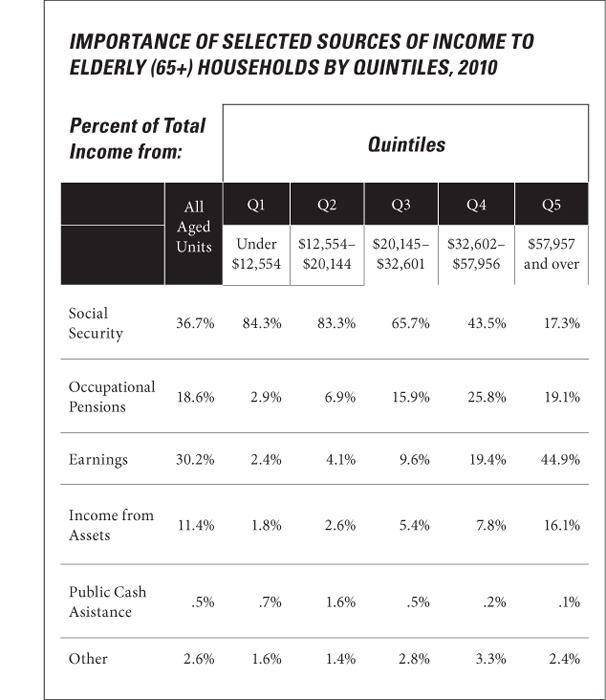

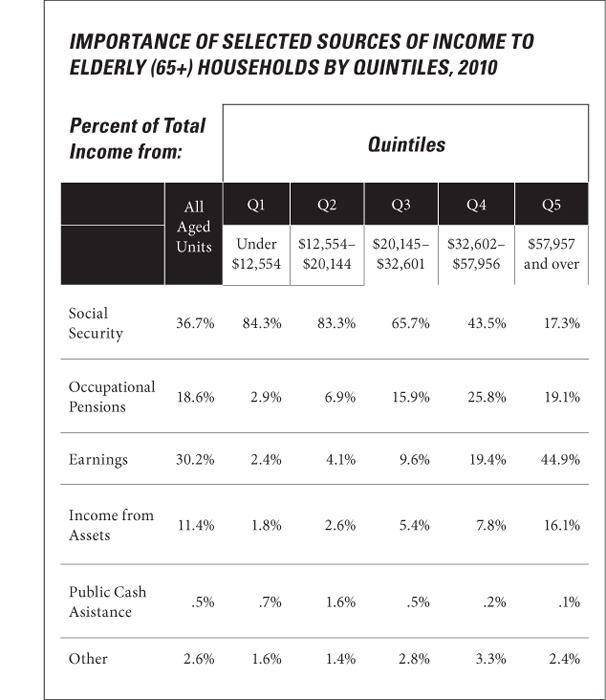

Sixty percent of households with at least one person aged sixty-five or over reported income of less than $32,602 in 2010 income About three-quarters of all the income going to those households comes from Social Security. Occupational pensions make significant contributions to the aggregate incomes going to households in the three highest quintiles, but fall short of Social Security, which is not surprising when considering that roughly six out of ten private-sector employees do not have private pension protections.

Without Social Security, the official U.S. poverty rate among the aged would jump from 9 percent to nearly 50 percent—about the same rate as in the 1920s and early 1930s, prior to the enactment of Social Security. Poverty rates for older Americans living alone and for minorities are even higher than the rate of poverty among all aged, and those subgroups are, on average, more dependent on Social Security.

Social Security Administration, Table 10.5, income of the Population 55 or Older, 2021, February 2012.

From the beginning, Social Security has been structured to address two goals—social adequacy along with individual equity. Social adequacy means that even the lowest benefits will provide at least a minimal level of support. The ideal, though not fully achieved, is that those who work their entire lives should not have to retire into poverty. Those who work and contribute should benefit from that work, and receive higher benefits than they would simply from means-tested welfare. Individual equity means that all workers receive a fair benefit in relation to their work effort and level of contributions. Social Security has been well designed to balance these twin goals.

One way these twin goals are achieved is through the use of a progressive benefit formula. The way Social Security calculates benefits is one of the most ingenious and important features of the program. Its benefit formula ensures that long-term, low-wage workers receive a proportionately larger benefit relative to their contributions, though a lower absolute dollar amount, than high-wage workers. At the same time, the Social Security contributions of high-wage workers are recognized by a larger monthly benefit in absolute dollar terms, but a proportionately smaller benefit relative to their contributions. For workers retiring at the full retirement age of sixty-six years in January 2012, Social Security benefits replaced about 26 percent of earnings for those with earnings consistently at the maximum taxable earnings ceiling, about 41 percent for average earners, and about 55 percent for those with earnings at 45 percent of median wage, which the year before was $26,965 or less than $519 a week.

Social Security’s protections are by far the most important life and disability safeguard available to virtually all the nation’s seventy-five million children under age eighteen. Through Social Security, working Americans who are married with two young children, for example, earn life-insurance protections with a present value around $550,000 dollars. They earn similar protections for themselves and their families in the event of a severe and permanent disability.

In 2013, 4.5 million dependent children—about 3.5 million under age nineteen and 1 million adults disabled before age twenty-two—received Social Security checks totaling about $2.7 billion per month. Another 3.4 million children who do not receive benefits live in households with one or more relatives who do. Social Security benefits lift 1.3 million children out of poverty.

As much as children need Social Security protections when young, those hoping to work, especially if they plan to have children or retire one day, also need it. The Social Security Administration estimates that 25 to 30 percent of twenty-year-olds will become disabled prior to age sixty-seven and one in eight will die. Disability insurance, a benefit rarely offered by employers, provides vital protection over the course of one’s life. Further, nothing approaches Social Security in terms of providing secure retirement-income protection. Neither stock-market fluctuations nor inflation undermines its value. As billions of dollars of pension and home-equity “wealth” disappeared in the Great Recession, there was no risk of Social Security failing to meet its obligations.

By providing an orderly way for individuals to pay for benefits during working years in exchange for protections against premature death, disability, and retirement, Social Security takes some of the tension out of family life and reinforces the dignity of many. Knowing that one’s parents have Social Security often frees up the generation in the middle to direct more family resources toward their own children.

Given what a central role Social Security plays in the lives of the overwhelming number of America’s families, it is no surprise that virtually every poll shows large majorities consider Social Security crucial to their and the nation’s well-being and do not want to see benefits cut. This is true across all demographic groups—women, people of color, old, young—as well as across the political spectrum—Democrats, independents, and Republicans, union and even Tea Party supporters.

While there is much skepticism, especially among young adults, about its future, Social Security remains one of the few public services that citizens are willing to pay for. A 2013 Matthew Greenwald & Associates online survey of two thousand people ages twenty and above, commissioned by the nonpartisan National Academy of Social Insurance, showed that “Americans value Social Security, want to improve benefits, and are willing to pay more to maintain and expand its benefit protections.” Specifically, the poll found that:

Roughly four out of five say they value Social Security for themselves, their families, and for the sound protection it provides to tens of millions of beneficiaries;

More than four-fifths say that benefits are too low for retirees and three-quarters favor improving retirement protections for working Americans;

and more than four out of five believe it should be preserved for future generations even if it requires increasing payroll-tax contributions.

Of course, like the nation’s highways, Social Security needs to be maintained. The system, a public trust, is carefully monitored. Political squabbling aside, the Congress has always managed to adjust the system when necessary.

The Social Security system as currently structured is fully affordable. Indeed, higher benefits are affordable. At its most expensive, around 2035, when most if not all of today’s baby-boom generation is fully retired, Social Security will cost, as a percentage of the nation’s gross domestic product, less than other industrialized countries such as Germany, France, and Japan spend on their old age Social Security programs in 2013.

The American program is conservatively managed. Every year, its board of trustees issues a report projecting Social Security’s future income and outgo for the next three-quarters of a century. This is a longer valuation than private pensions use and longer, indeed, than most other countries use for their Social Security programs. The most recent report indicates that over the next seventy-five years, Social Security will have a projected shortfall of less than 1 percent of GDP.

That shortfall could be eliminated by increasing the rate at which Social Security contributions are assessed by just 1.31 percentage points to 7.51 percent of covered wages, but there are much more progressive ways to eliminate the shortfall. Several modest changes could ensure that the program is fully funded for everyone alive today. One change we believe should be made is increasing the maximum amount of wages on which Social Security’s contributions are assessed. Contributions are assessed only on the wages that are insured against loss.

Congress has expressed its intent that 90 percent of all wages be insured against loss, but because wages at the top have grown so much faster than average wages over the last few decades, the percentage of wages covered has declined. Restoring the maximum so it once again covers 90 percent of all wages would eliminate about a third of the projected shortfall. Gradually phasing out the maximum so that high-income employers eventually pay the same rate as the vast majority of their employees on all their earnings would, depending on how this change is structured, eliminate roughly 80 to 90 percent of the projected shortfall. It would also mean somewhat increased benefits for higher-income workers.

Other streams of revenue that could eliminate Social Security’s projected shortfall while addressing income inequality would be a modest tax on annual incomes above $1 million, or a modest tax on financial speculation. Numerous other approaches exist. All would impose modest increased costs on those at the top without cutting Social Security’s modest, but vital, benefits.

Since it was first proposed in 1935, many conservatives have vehemently opposed Social Security. They assert that Social Security’s universal wage insurance is an inappropriate role of government. They believe Social Security somehow restricts freedom and turns the nation into a collection of people dependent on government. Yet Americans continue to work hard while continually demonstrating overwhelmingly support for Social Security.

This popularity is the reason it is hard to find any politician who says he or she does not support Social Security; they all say they want to “strengthen” it. Generally, one can only discern their true motives by studying what they are proposing. Despite the time-tested ability of Social Security to meet all its obligations, in good times and bad, there are those who falsely claim it is unsustainable. Others, in the name of fiscal austerity or claims about insolvency, want to compromise Social Security’s basic protections by reducing its modest benefits through subtle but damaging changes. One would be cutting the cost of living adjustment, which prevents benefits from eroding over time. Another proposal is to raise the retirement age, which amounts to an across-the-board benefit cut for retirees, a cut which would fall hardest on those in physically demanding jobs or in poor health. There are, and will be, other proposals to portray benefit cuts as strengthening the system.

The worst proposals are to radically transform Social Security by privatizing, which would put people at the mercy of the stock and bonds markets as well as cost much more to administer or to add means-testing which would deny benefits to higher-income workers. Either of these ideas would destroy the fundamental features that have made Social Security so successful, and wildly popular, which is what opponents of Social Security want to destroy so they can end the program.

Occasionally the veil slips, and politicians let their true views out. At a private fund-raiser on May 17, 2012, presidential candidate Mitt Romney said, in an apparent reference to, among others, Social Security beneficiaries, “There are 47 percent of the people . . . who are dependent on government, who believe that they are victims, who believe that government has a responsibility to care for them.” Similarly, his vice presidential running mate, Congressman Paul Ryan, has divided Americans into so-called takers and makers. The reality is that Social Security is not a government handout. It is a benefit that is earned and paid for through hard work.

Because of all the organized attacks based on falsehoods told about Social Security, the public lacks confidence in its future, concerned that it may not be there when they, their children, and grandchildren need it. Ask most young people whether they think Social Security will be there when they need it, and a large majority says “no.”

Ask those same young people whether they think Social Security benefits, averaging just around $15,000 a year for today’s retired workers, should be increased, and most answer “yes.” These young people seem to understand that behind all the numbers, all the technical talk about Social Security, are real people—their grandparents, parents, a classmate whose father died, and another whose mother is severely disabled. And, as the economy changes, it becomes increasingly apparent that they, like their parents, will need this system as they travel through life.

Americans today face a serious retirement-income crisis. Data published by the Retirement Research Center at Boston College suggest that nearly two-thirds of today’s workers will be unable to maintain their standards of living in retirement, even if they work until age sixty-five. Nevertheless, political and media elites seem to think that still larger cuts are sensible—both for today’s and tomorrow’s beneficiaries—and only a courageous few have voiced the need to expand, not cut, Social Security.

Today’s debate is less about today’s seniors than tomorrow’s. Our nation’s children have a huge stake in the preservation of Social Security. Even more than their parents and grandparents, they stand to gain the most from the organized efforts of older Americans to strengthen the program, not cut it. The United States can unquestionably afford Social Security. The issue about its future is not one of mathematics or even demographics, but politics.

The case for expanding Social Security is strong. It is more efficient, secure, universal, and fair in its distribution than any private-sector counterpart is or could ever be, no matter how structured. The reason? Wage insurance works best when all workers are covered under the same plan and the coverage starts at the beginning of their working lives. The only entity that can mandate this kind of universal program is the federal government and it has.

In reality, Social Security is the nation’s most successful, popular, and just social program, the “poster child” for government working well on behalf of the American people and playing a major role in reducing inequality.

![]()

*You can look up the latest data, posted each month, by the Social Security Administration, Office of the Actuary.