4

An Investigation of the Laws of Thought on Which Are Founded the Mathematical Theories of Logic and Probabilities (1854)

George Boole

When George Boole (1815–1864) was a student two millennia after Aristotle, the Prior Analytics was still a standard logic text. Astonishing advances in continuous mathematics had been made in the eighteenth century. The orbits of the planets and the behavior of other objects in motion could now be accurately—if tediously—determined by calculation. Yet in spite of Leibniz’s vision of a calculus of ideas to match his calculus of infinitesimals, and his tentative start at developing formal rules of reasoning, logic was barely more systematic than it had been in ancient times. Boole realized that logic was a branch of mathematics, and as such was subject to rules that could be the basis for calculations about propositions. His goal was “to give expression in this treatise to the fundamental laws of reasoning in the symbolical language of a Calculus” (§4.1).

The mathematician George Peacock, a member of a Cambridge intellectual circle that included Charles Babbage, foreshadowed Boole when, in his Treatise on Algebra (Peacock, 1830), he propounded a view of algebra as “the science of general reasoning by symbolical language.” Yet the publication of Boole’s Laws of Thought marked a crucial moment in the development of computer science. His reduction of logic to an algebra of true and false variables influenced other contemporary logicians, including Augustus De Morgan (remembered today for his laws) and John Venn (remembered for his diagrams). A few years after publication of The Laws of Thought, Boole’s countryman William Jevons (1835–1882) built a “logic piano” for doing calculations with the truth-values of propositions. It wasn’t a useful device, being restricted to four propositions, but it was the first mechanization of what we now know as boolean logic. Boole’s conception of logical algebra in fact extends beyond boolean logic to what we would now call naïve set theory and probability theory. On page 30, Boole explains his word “class” to mean what we now call a set, and explicitly states the possibility that a class might be empty, a singleton, or the entire universe. Boole articulates that a variable x can be treated indifferently as a proposition stating that an individual has a given property, or as a class of entities having that property. He then goes on to use “+” for union, “−” for difference, and “×” or juxtaposition for intersection, and to derive the commutative and distributive laws, and to infer the duality or dichotomy principle (nothing can belong to a set and to its complement) algebraically from idempotency (the intersection of a set with itself is the same set). The book is laid out as a series of definitions, propositions, and “rules,” all designed to instruct in algebraic manipulation of logical formulas (and, later in the work, of probabilities).

George Boole was a largely self-taught mathematician, the son of an English shoemaker and the beneficiary of only primary education. He managed to publish serious mathematical research in his twenties while supporting himself as a schoolmaster. He won a professorship a decade later at the new Queen’s College at Cork in Ireland, one of three colleges Queen Victoria had simultaneously endowed “for the advancement of learning in Ireland” (the other two were in Belfast and Galway). It was from this perch, away from the great mathematical centers of Oxford and Cambridge, that Boole wrote his unique opus, from which we include a small selection.

In these pages Boole patiently explains some of the rules and methods of propositional logic, including the commutative law. It all seems quite routine to us now, so used are we to the then-novel idea that true and false can be manipulated algebraically. Almost a century later, Claude Shannon incorporated Boole’s ideas wholesale into the emerging world of digital circuitry (chapter 8). Our selection closes with the idea of a truth-function and the insight that such a function can be decomposed into subfunctions by fixing the value of one variable to be true or false. Boole likened this process to a Taylor series expansion of a differentiable function.

Boole died at age 49 of an infection contracted while walking three miles to his lecture in the cold Irish rain (MacHale, 2014).

4.1 Nature and Design of This Work

THE design of the following treatise is to investigate the fundamental laws of those operations of the mind by which reasoning is performed; to give expression to them in the symbolical language of a Calculus, and upon this foundation to establish the science of Logic and construct its method; to make that method itself the basis of a general method for the application of the mathematical doctrine of Probabilities; and, finally, to collect from the various elements of truth brought to view in the course of these inquiries some probable intimations concerning the nature and constitution of the human mind. …

4.2 Of Signs in General, and of the Signs Appropriate to the Science of Logic in Particular; Also of the Laws to Which That Class of Signs Are Subject

4.2.1 That Language is an instrument of human reason, and not merely a medium for the expression of thought, is a truth generally admitted. It is proposed in this chapter to inquire what it is that renders Language thus subservient to the most important of our intellectual faculties. In the various steps of this inquiry we shall be led to consider the constitution of Language, considered as a system adapted to an end or purpose; to investigate its elements; to seek to determine their mutual relation and dependence; and to inquire in what manner they contribute to the attainment of the end to which, as co-ordinate parts of a system, they have respect. …

4.2.2 The elements of which all language consists are signs or symbols. Words are signs. Sometimes they are said to represent things; sometimes the operations by which the mind combines together the simple notions of things into complex conceptions; sometimes they express the relations of action, passion, or mere quality, which we perceive to exist among the objects of our experience; sometimes the emotions of the perceiving mind. But words, although in this and in other ways they fulfil the office of signs, or representative symbols, are not the only signs which we are capable of employing. Arbitrary marks, which speak only to the eye, and arbitrary sounds or actions, which address themselves to some other sense, are equally of the nature of signs, provided that their representative office is defined and understood. In the mathematical sciences, letters, and the symbols +, −, =, &c., are used as signs, although the term “sign” is applied to the latter class of symbols, which represent operations or relations, rather than to the former, which represent the elements of number and quantity. As the real import of a sign does not in any way depend upon its particular form or expression, so neither do the laws which determine its use. In the present treatise, however, it is with written signs that we have to do, and it is with reference to these exclusively that the term “sign” will be employed.

The essential properties of signs are enumerated in the following definition.

Definition.—A sign is an arbitrary mark, having a fixed interpretation, and susceptible of combination with other signs in subjection to fixed laws dependent upon their mutual interpretation.

…

4.2.4 The analysis and classification of those signs by which the operations of reasoning are conducted will be considered in the following Proposition:

All the operations of Language, as an instrument of reasoning, may be conducted by a system of signs composed of the following elements, viz.:

1st. Literal symbols, as x, y, &c., representing things as subjects of our conceptions.

2nd. Signs of operation, as +, −, ×, standing for those operations of the mind by which the conceptions of things are combined or resolved so as to form new conceptions involving the same elements.

3rd. The sign of identity, =.

And these symbols of Logic are in their use subject to definite laws, partly agreeing with and partly differing from the laws of the corresponding symbols in the science of Algebra.

Let it be assumed as a criterion of the true elements of rational discourse, that they should be susceptible of combination in the simplest forms and by the simplest laws, and thus combining should generate all other known and conceivable forms of language; and adopting this principle, let the following classification be considered.

4.2.5 CLASS I. Appellative or descriptive signs, expressing either the name of a thing, or some quality or circumstance belonging to it.

To this class we may obviously refer the substantive proper or common, and the adjective. These may indeed be regarded as differing only in this respect, that the former expresses the substantive existence of the individual thing or things to which it refers; the latter implies that existence. If we attach to the adjective the universally understood subject “being” or “thing,” it becomes virtually a substantive, and may for all the essential purposes of reasoning be replaced by the substantive. Whether or not, in every particular of the mental regard, it is the same thing to say, “Water is a fluid thing,” as to say, “Water is fluid”; it is at least equivalent in the expression of the processes of reasoning.

It is clear also, that to the above class we must refer any sign which may conventionally be used to express some circumstance or relation, the detailed exposition of which would involve the use of many signs. The epithets of poetic diction are very frequently of this kind. They are usually compounded adjectives, singly fulfilling the office of a many-worded description. Homer’s “deep-eddying ocean” embodies a virtual description in the single word βαθυδίνης. And conventionally any other description addressed either to the imagination or to the intellect might equally be represented by a single sign, the use of which would in all essential points be subject to the same laws as the use of the adjective “good” or “great.” Combined with the subject “thing,” such a sign would virtually become a substantive; and by a single substantive the combined meaning both of thing and quality might be expressed.

4.2.6 Now, as it has been defined that a sign is an arbitrary mark, it is permissible to replace all signs of the species above described by letters. Let us then agree to represent the class of individuals to which a particular name or description is applicable, by a single letter, as x. If the name is “men,” for instance, let x represent “all men,” or the class “men.” By a class is usually meant a collection of individuals, to each of which a particular name or description may be applied; but in this work the meaning of the term will be extended so as to include the case in which but a single individual exists, answering to the required name or description, as well as the cases denoted by the terms “nothing” and “universe,” which as “classes” should be understood to comprise respectively “no beings,” “all beings.” Again, if an adjective, as “good,” is employed as a term of description, let us represent by a letter, as y, all things to which the description “good” is applicable, i.e. “all good things,” or the class “good things.” Let it further be agreed, that by the combination xy shall be represented that class of things to which the names or descriptions represented by x and y are simultaneously applicable. Thus, if x alone stands for “white things,” and y for “sheep,” let xy stand for “white sheep”; and in like manner, if z stand for “horned things,” and x and y retain their previous interpretations, let zxy represent “horned white sheep,” i.e. that collection of things to which the name “sheep,” and the descriptions “white” and “horned” are together applicable.

Let us now consider the laws to which the symbols x, y, &c., used in the above sense, are subject.

4.2.7 First, it is evident, that according to the above combinations, the order in which two symbols are written is indifferent. The expressions xy and yx equally represent that class of things to the several members of which the names or descriptions x and y are together applicable. Hence we have,

In the case of x representing white things, and y sheep, either of the members of this equation will represent the class of “white sheep.” There may be a difference as to the order in which the conception is formed, but there is none as to the individual things which are comprehended under it. In like manner, if x represent “estuaries,” and y “rivers,” the expressions xy and yx will indifferently represent “rivers that are estuaries,” or “estuaries that are rivers,” the combination in this case being in ordinary language that of two substantives, instead of that of a substantive and an adjective as in the previous instance.

Let there be a third symbol, as z, representing that class of things to which the term “navigable” is applicable, and any one of the following expressions, zxy, zyx, xyz, &c., will represent the class of “navigable rivers that are estuaries.”

If one of the descriptive terms should have some implied reference to another, it is only necessary to include that reference expressly in its stated meaning, in order to render the above remarks still applicable. Thus, if x represent “wise” and y “counsellor,” we shall have to define whether x implies wisdom in the absolute sense, or only the wisdom of counsel. With such definition the law xy = yx continues to be valid.

We are permitted, therefore, to employ the symbols x, y, z, &c., in the place of the substantives, adjectives, and descriptive phrases subject to the rule of interpretation, that any expression in which several of these symbols are written together shall represent all the objects or individuals to which their several meanings are together applicable, and to the law that the order in which the symbols succeed each other is indifferent.

As the rule of interpretation has been sufficiently exemplified, I shall deem it unnecessary always to express the subject “things” in defining the interpretation of a symbol used for an adjective. When I say, let x represent “good,” it will be understood that x only represents “good” when a subject for that quality is supplied by another symbol, and that, used alone, its interpretation will be “good things.”

4.2.8 Concerning the law above determined, the following observations, which will also be more or less appropriate to certain other laws to be deduced hereafter, may be added.

First, I would remark, that this law is a law of thought, and not, properly speaking, a law of things. Difference in the order of the qualities or attributes of an object, apart from all questions of causation, is a difference in conception merely. The law (4.1) expresses as a general truth, that the same thing may be conceived in different ways, and states the nature of that difference; and it does no more than this.

Secondly, as a law of thought, it is actually developed in a law of Language, the product and the instrument of thought. Though the tendency of prose writing is toward uniformity, yet even there the order of sequence of adjectives absolute in their meaning, and applied to the same subject, is indifferent, but poetic diction borrows much of its rich diversity from the extension of the same lawful freedom to the substantive also. The language of Milton is peculiarly distinguished by this species of variety. Not only does the substantive often precede the adjectives by which it is qualified, but it is frequently placed in their midst. In the first few lines of the invocation to Light, we meet with such examples as the following:

“Offspring of heaven first-born.”

“The rising world of waters dark and deep.”

“Bright effluence of bright essence increate.”

Now these inverted forms are not simply the fruits of a poetic license. They are the natural expressions of a freedom sanctioned by the intimate laws of thought, but for reasons of convenience not exercised in the ordinary use of language.

Thirdly, the law expressed by (4.1) may be characterized by saying that the literal symbols x, y, z, are commutative, like the symbols of Algebra. In saying this, it is not affirmed that the process of multiplication in Algebra, of which the fundamental law is expressed by the equation xy = yx, possesses in itself any analogy with that process of logical combination which xy has been made to represent above; but only that if the arithmetical and the logical process are expressed in the same manner, their symbolical expressions will be subject to the same formal law. The evidence of that subjection is in the two cases quite distinct.

4.2.9 As the combination of two literal symbols in the form xy expresses the whole of that class of objects to which the names or qualities represented by x and y are together applicable, it follows that if the two symbols have exactly the same signification, their combination expresses no more than either of the symbols taken alone would do. In such case we should therefore have xy = x. As y is, however, supposed to have the same meaning as x, we may replace it in the above equation by x, and we thus get xx = x. Now in common Algebra the combination xx is more briefly represented by x2. Let us adopt the same principle of notation here; for the mode of expressing a particular succession of mental operations is a thing in itself quite as arbitrary as the mode of expressing a single idea or operation. In accordance with this notation, then, the above equation assumes the form

and is, in fact, the expression of a second general law of those symbols by which names, qualities, or descriptions, are symbolically represented.

The reader must bear in mind that although the symbols x and y in the examples previously formed received significations distinct from each other, nothing prevents us from attributing to them precisely the same signification. It is evident that the more nearly their actual significations approach to each other, the more nearly does the class of things denoted by the combination xy approach to identity with the class denoted by x, as well as with that denoted by y. The case supposed in the demonstration of the equation (4.2) is that of absolute identity of meaning. The law which it expresses is practically exemplified in language. To say “good, good,” in relation to any subject, though a cumbrous and useless pleonasm, is the same as to say “good.” Thus “good, good” men, is equivalent to “good” men. Such repetitions of words are indeed sometimes employed to heighten a quality or strengthen an affirmation. But this effect is merely secondary and conventional; it is not founded in the intrinsic relations of language and thought. Most of the operations which we observe in nature, or perform ourselves, are of such a kind that their effect is augmented by repetition, and this circumstance prepares us to expect the same thing in language, and even to use repetition when we design to speak with emphasis. But neither in strict reasoning nor in exact discourse is there any just ground for such a practice.

4.2.10 We pass now to the consideration of another class of the signs of speech, and of the laws connected with their use.

4.2.11 CLASS II. Signs of those mental operations whereby we collect parts into a whole, or separate a whole into its parts.

We are not only capable of entertaining the conceptions of objects, as characterized by names, qualities, or circumstances, applicable to each individual of the group under consideration, but also of forming the aggregate conception of a group of objects consisting of partial groups, each of which is separately named or described. For this purpose we use the conjunctions “and,” “or,” &c. “Trees and minerals,” “barren mountains, or fertile vales,” are examples of this kind. In strictness, the words “and,” “or,” interposed between the terms descriptive of two or more classes of objects, imply that those classes are quite distinct, so that no member of one is found in another. In this and in all other respects the words “and” “or” are analogous with the sign + in algebra, and their laws are identical. Thus the expression “men and women” is, conventional meanings set aside, equivalent with the expression “women and men.” Let x represent “men,” y, “women”; and let + stand for “and” and “or,” then we have x + y = y + x, an equation which would equally hold true if x and y represented numbers, and + were the sign of arithmetical addition.

Let the symbol z stand for the adjective “European,” then since it is, in effect, the same thing to say “European men and women,” as to say “European men and European women,” we have

And this equation also would be equally true were x, y, and z symbols of number, and were the juxtaposition of two literal symbols to represent their algebraic product, just as in the logical signification previously given, it represents the class of objects to which both the epithets conjoined belong.

The above are the laws which govern the use of the sign +, here used to denote the positive operation of aggregating parts into a whole. But the very idea of an operation effecting some positive change seems to suggest to us the idea of an opposite or negative operation, having the effect of undoing what the former one has done. Thus we cannot conceive it possible to collect parts into a whole, and not conceive it also possible to separate a part from a whole. This operation we express in common language by the sign except, as, “All men except Asiatics,” “All states except those which are monarchical.” Here it is implied that the things excepted form a part of the things from which they are excepted. As we have expressed the operation of aggregation by the sign +, so we may express the negative operation above described by − minus. Thus if x be taken to represent men, and y, Asiatics, i.e. Asiatic men, then the conception of “All men except Asiatics” will be expressed by x − y. And if we represent by x, “states,” and by y the descriptive property “having a monarchical form,” then the conception of “All states except those which are monarchical” will be expressed by x − xy.

As it is indifferent for all the essential purposes of reasoning whether we express excepted cases first or last in the order of speech, it is also indifferent in what order we write any series of terms, some of which are affected by the sign −. Thus we have, as in the common algebra,

Still representing by x the class “men,” and by y “Asiatics,” let z represent the adjective “white.” Now to apply the adjective “white” to the collection of men expressed by the phrase “Men except Asiatics,” is the same as to say, “White men, except white Asiatics.” Hence we have

This is also in accordance with the laws of ordinary algebra.

The equations (4.3) and (4.4) may be considered as exemplification of a single general law, which may be stated by saying, that the literal symbols, x, y, z, &c. are distributive in their operation. The general fact which that law expresses is this, viz.: If any quality or circumstance is ascribed to all the members of a group, formed either by aggregation or exclusion of partial groups, the resulting conception is the same as if the quality or circumstance were first ascribed to each member of the partial groups, and the aggregation or exclusion effected afterwards. That which is ascribed to the members of the whole is ascribed to the members of all its parts, howsoever those parts are connected together.

4.2.12 CLASS III. Signs by which relation is expressed, and by which we form propositions.

Though all verbs may with propriety be referred to this class, it is sufficient for the purposes of Logic to consider it as including only the substantive verb is or are, since every other verb may be resolved into this element, and one of the signs included under Class I. For as those signs are used to express quality or circumstance of every kind, they may be employed to express the active or passive relation of the subject of the verb, considered with reference either to past, to present, or to future time. Thus the Proposition, “Cæsar conquered the Gauls,” may be resolved into “Cæsar is he who conquered the Gauls.” The ground of this analysis I conceive to be the following:—Unless we understand what is meant by having conquered the Gauls, i.e. by the expression “One who conquered the Gauls,” we cannot understand the sentence in question. It is, therefore, truly an element of that sentence; another element is “Cæsar,” and there is yet another required, the copula is to show the connexion of these two. I do not, however, affirm that there is no other mode than the above of contemplating the relation expressed by the proposition, “Cæsar conquered the Gauls”; but only that the analysis here given is a correct one for the particular point of view which has been taken, and that it suffices for the purposes of logical deduction. It may be remarked that the passive and future participles of the Greek language imply the existence of the principle which has been asserted, viz.: that the sign is or are may be regarded as an element of every personal verb.

4.2.13 The above sign, is or are may be expressed by the symbol =. The laws, or as would usually be said, the axioms which the symbol introduces, are next to be considered. Let us take the Proposition, “The stars are the suns and the planets,” and let us represent stars by x, suns by y, and planets by z; we have then

Now if it be true that the stars are the suns and the planets, it will follow that the stars, except the planets, are suns. This would give the equation x − z = y, which must therefore be a deduction from (4.5). Thus a term z has been removed from one side of an equation to the other by changing its sign. This is in accordance with the algebraic rule of transposition.

But instead of dwelling upon particular cases, we may at once affirm the general axioms:—

1st. If equal things are added to equal things, the wholes are equal.

2nd. If equal things are taken from equal things, the remainders are equal.

And it hence appears that we may add or subtract equations, and employ the rule of transposition above given just as in common algebra.

Again: If two classes of things, x and y, be identical, that is, if all the members of the one are members of the other, then those members of the one class which possess a given property z will be identical with those members of the other which possess the same property z. Hence if we have the equation x = y; then whatever class or property z may represent, we have also zx = zy.

This is formally the same as the algebraic law:—If both members of an equation are multiplied by the same quantity, the products are equal.

In like manner it may be shown that if the corresponding members of two equations are multiplied together, the resulting equation is true.

4.2.14 Here, however, the analogy of the present system with that of algebra, as commonly stated, appears to stop. Suppose it true that those members of a class x which possess a certain property z are identical with those members of a class y which possess the same property z, it does not follow that the members of the class x universally are identical with the members of the class y. Hence it cannot be inferred from the equation zx = zy, that the equation x = y is also true. In other words, the axiom of algebraists, that both sides of an equation may be divided by the same quantity, has no formal equivalent here. I say no formal equivalent, because, in accordance with the general spirit of these inquiries, it is not even sought to determine whether the mental operation which is represented by removing a logical symbol, z, from a combination zx, is in itself analogous with the operation of division in Arithmetic. That mental operation is indeed identical with what is commonly termed Abstraction, and it will hereafter appear that its laws are dependent upon the laws already deduced in this chapter. What has now been shown is, that there does not exist among those laws anything analogous in form with a commonly received axiom of Algebra.

But a little consideration will show that even in common algebra that axiom does not possess the generality of those other axioms which have been considered. The deduction of the equation x = y from the equation zx = zy is only valid when it is known that z is not equal to 0. If then the value z = 0 is supposed to be admissible in the algebraic system, the axiom above stated ceases to be applicable, and the analogy before exemplified remains at least unbroken.

4.2.15 However, it is not with the symbols of quantity generally that it is of any importance, except as a matter of speculation, to trace such affinities. We have seen (§4.2.9) that the symbols of Logic are subject to the special law, x2 = x. Now of the symbols of Number there are but two, viz. 0 and 1, which are subject to the same formal law. We know that 02 = 0, and that 12 = 1; and the equation x2 = x, considered as algebraic, has no other roots than 0 and 1. Hence, instead of determining the measure of formal agreement of the symbols of Logic with those of Number generally, it is more immediately suggested to us to compare them with symbols of quantity admitting only of the values 0 and 1. Let us conceive, then, of an Algebra in which the symbols x, y, z, etc. admit indifferently of the values 0 and 1, and of these values alone. The laws, the axioms, and the processes, of such an Algebra will be identical in their whole extent with the laws, the axioms, and the processes of an Algebra of Logic. Difference of interpretation will alone divide them. Upon this principle the method of the following work is established.

4.2.16 It now remains to show that those constituent parts of ordinary language which have not been considered in the previous sections of this chapter are either resolvable into the same elements as those which have been considered, or are subsidiary to those elements by contributing to their more precise definition.

The substantive, the adjective, and the verb, together with the particles and, except, we have already considered. The pronoun may be regarded as a particular form of the substantive or the adjective. The adverb modifies the meaning of the verb, but does not affect its nature. Prepositions contribute to the expression of circumstance or relation, and thus tend to give precision and detail to the meaning of the literal symbols. The conjunctions if, either, or, are used chiefly in the expression of relation among propositions, and it will hereafter be shown that the same relations can be completely expressed by elementary symbols analogous in interpretation, and identical in form and law with the symbols whose use and meaning have been explained in this chapter. As to any remaining elements of speech, it will, upon examination, be found that they are used either to give a more definite significance to the terms of discourse, and thus enter into the interpretation of the literal symbols already considered, or to express some emotion or state of feeling accompanying the utterance of a proposition, and thus do not belong to the province of the understanding, with which alone our present concern lies. Experience of its use will testify to the sufficiency of the classification which has been adopted.

4.3 Derivation of the Laws of the Symbols of Logic from the Laws of the Operations of the Human Mind …

4.3.12 The remainder of this chapter will be occupied with questions relating to that law of thought whose expression is x2 = x (§4.2.9), a law which, as has been implied (§4.2.15), forms the characteristic distinction of the operations of the mind in its ordinary discourse and reasoning, as compared with its operations when occupied with the general algebra of quantity. An important part of the following inquiry will consist in proving that the symbols 0 and 1 occupy a place, and are susceptible of an interpretation, among the symbols of Logic; and it may first be necessary to show how particular symbols, such as the above, may with propriety and advantage be employed in the representation of distinct systems of thought.

The ground of this propriety cannot consist in any community of interpretation. For in systems of thought so truly distinct as those of Logic and Arithmetic (I use the latter term in its widest sense as the science of Number), there is, properly speaking, no community of subject. The one of them is conversant with the very conceptions of things, the other takes account solely of their numerical relations. But inasmuch as the forms and methods of any system of reasoning depend immediately upon the laws to which the symbols are subject, and only mediately, through the above link of connexion, upon their interpretation, there may be both propriety and advantage in employing the same symbols in different systems of thought, provided that such interpretations can be assigned to them as shall render their formal laws identical, and their use consistent. The ground of that employment will not then be community of interpretation, but the community of the formal laws, to which in their respective systems they are subject. Nor must that community of formal laws be established upon any other ground than that of a careful observation and comparison of those results which are seen to flow independently from the interpretations of the systems under consideration.

These observations will explain the process of inquiry adopted in the following Proposition. The literal symbols of Logic are universally subject to the law whose expression is x2 = x. Of the symbols of Number there are two only, 0 and 1, which satisfy this law. But each of these symbols is also subject to a law peculiar to itself in the system of numerical magnitude, and this suggests the inquiry, what interpretations must be given to the literal symbols of Logic, in order that the same peculiar and formal laws may be realized in the logical system also.

4.3.13 To determine the logical value and significance of the symbols 0 and 1. The symbol 0, as used in Algebra, satisfies the following formal law,

whatever number y may represent. That this formal law may be obeyed in the system of Logic, we must assign to the symbol 0 such an interpretation that the class represented by 0y may be identical with the class represented by 0, whatever the class y may be. A little consideration will show that this condition is satisfied if the symbol 0 represent Nothing. In accordance with a previous definition, we may term Nothing a class. In fact, Nothing and Universe are the two limits of class extension, for they are the limits of the possible interpretations of general names, none of which can relate to fewer individuals than are comprised in Nothing, or to more than are comprised in the Universe.

Now whatever the class y may be, the individuals which are common to it and to the class “Nothing” are identical with those comprised in the class “Nothing,” for they are none. And thus by assigning to 0 the interpretation Nothing, the law (4.6) is satisfied; and it is not otherwise satisfied consistently with the perfectly general character of the class y.

Secondly, the symbol 1 satisfies in the system of Number the following law, viz.,

whatever number y may represent. And this formal equation being assumed as equally valid in the system of this work, in which 1 and y represent classes, it appears that the symbol 1 must represent such a class that all the individuals which are found in any proposed class y are also all the individuals 1y that are common to that class y and the class represented by 1. A little consideration will here show that the class represented by 1 must be “the Universe,” since this is the only class in which are found all the individuals that exist in any class. Hence the respective interpretations of the symbols 0 and 1 in the system of Logic are Nothing and Universe.

4.3.14 As with the idea of any class of objects as “men,” there is suggested to the mind the idea of the contrary class of beings which are not men; and as the whole Universe is made up of these two classes together, since of every individual which it comprehends we may affirm either that it is a man, or that it is not a man, it becomes important to inquire how such contrary names are to be expressed. Such is the object of the following Proposition.

If x represent any class of objects, then will 1 − x represent the contrary or supplementary class of objects., i.e. the class including all objects which are not comprehended in the class x.

For greater distinctness of conception let x represent the class men, and let us express, according to the last Proposition, the Universe by 1; now if from the conception of the Universe, as consisting of “men” and “not-men,” we exclude the conception of “men,” the resulting conception is that of the contrary class, “not-men.” Hence the class “not-men” will be represented by 1 −x. And, in general, whatever class of objects is represented by the symbol x, the contrary class will be expressed by 1 − x.

4.3.15 Although the following Proposition belongs in strictness to a future chapter of this work, devoted to the subject of maxims or necessary truths, yet, on account of the great importance of that law of thought to which it relates, it has been thought proper to introduce it here.

That axiom of metaphysicians which is termed the principle of contradiction, and which affirms that it is impossible for any being to possess a quality, and at the same time not to possess it, is a consequence of the fundamental law of thought, whose expression is x2 = x.

Let us write this equation in the form x − x2 = 0, whence we have

both these transformations being justified by the axiomatic laws of combination and transposition (§4.2.13). Let us, for simplicity of conception, give to the symbol x the particular interpretation of men, then 1 − x will represent the class of “not-men” (§4.3.14). Now the formal product of the expressions of two classes represents that class of individuals which is common to them both (§4.2.9). Hence x(1 − x) will represent the class whose members are at once “men,” and “not men,” and the equation (4.7) thus express the principle, that a class whose members are at the same time men and not men does not exist. In other words, that it is impossible for the same individual to be at the same time a man and not a man. Now let the meaning of the symbol x be extended from the representing of “men,” to that of any class of beings characterized by the possession of any quality whatever; and the equation (4.7) thus will then express that it is impossible for a being to possess a quality and not to possess that quality at the same time. But this is identically that “principle of contradiction” which Aristotle has described as the fundamental axiom of all philosophy. “It is impossible that the same quality should both belong and not belong to the same thing. … This is the most certain of all principles. … Wherefore they who demonstrate refer to this as an ultimate opinion. For it is by nature the source of all the other axioms.”

The above interpretation has been introduced not on account of its immediate value in the present system, but as an illustration of a significant fact in the philosophy of the intellectual powers, viz., that what has been commonly regarded as the fundamental axiom of metaphysics is but the consequence of a law of thought, mathematical in its form. I desire to direct attention also to the circumstance that the equation (4.7) thus in which that fundamental law of thought is expressed is an equation of the second degree. …

4.3.16 The law of thought expressed by the equation (4.7) thus will, for reasons which are made apparent by the above discussion, be occasionally referred to as the “law of duality.”

4.4 Of the Division of Propositions into the Two Classes of “Primary” and “Secondary,” of the Characteristic Properties of Those Classes, and of the Laws of the Expression of Primary Propositions

4.4.1 The laws of those mental operations which are concerned in the processes of Conception or Imagination having been investigated, and the corresponding laws of the symbols by which they are represented explained, we are led to consider the practical application of the results obtained: first, in the expression of the complex terms of propositions; secondly, in the expression of propositions; and lastly, in the construction of a general method of deductive analysis. In the present chapter we shall be chiefly concerned with the first of these objects, as an introduction to which it is necessary to establish the following Proposition:

All logical propositions may be considered as belonging to one or the other of two great classes, to which the respective names of “Primary” or “Concrete Propositions,” and “Secondary” or “Abstract Propositions,” may be given.

Every assertion that we make may be referred to one or the other of the two following kinds. Either it expresses a relation among things, or it expresses, or is equivalent to the expression of, a relation among propositions. An assertion respecting the properties of things, or the phænomena which they manifest, or the circumstances in which they are placed, is, properly speaking, the assertion of a relation among things. To say that “snow is white,” is for the ends of logic equivalent to saying, that “snow is a white thing.” An assertion respecting facts or events, their mutual connexion and dependence, is, for the same ends, generally equivalent to the assertion, that such and such propositions concerning those events have a certain relation to each other as respects their mutual truth or falsehood. The former class of propositions, relating to things, I call “Primary”; the latter class, relating to propositions, I call “Secondary.” The distinction is in practice nearly but not quite co-extensive with the common logical distinction of propositions as categorical or hypothetical.

For instance, the propositions, “The sun shines,” “The earth is warmed,” are primary; the proposition, “If the sun shines the earth is warmed,” is secondary. To say, “The sun shines,” is to say, “The sun is that which shines,” and it expresses a relation between two classes of things, viz., “the sun” and “things which shine.” The secondary proposition, however, given above, expresses a relation of dependence between the two primary propositions, “The sun shines,” and “The earth is warmed.” I do not hereby affirm that the relation between these propositions is, like that which exists between the facts which they express, a relation of causality, but only that the relation among the propositions so implies, and is so implied by, the relation among the facts, that it may for the ends of logic be used as a fit representative of that relation.

4.4.2 If instead of the proposition, “The sun shines,” we say, “It is true that the sun shines,” we then speak not directly of things, but of a proposition concerning things, viz., of the proposition, “The sun shines.” And, therefore, the proposition in which we thus speak is a secondary one. Every primary proposition may thus give rise to a secondary proposition, viz., to that secondary proposition which asserts its truth, or declares its falsehood.

It will usually happen, that the particles if, either, or, will indicate that a proposition is secondary; but they do not necessarily imply that such is the case. The proposition, “Animals are either rational or irrational,” is primary. It cannot be resolved into “Either animals are rational or animals are irrational,” and it does not therefore express a relation of dependence between the two propositions connected together in the latter disjunctive sentence. The particles, either, or, are in fact no criterion of the nature of propositions, although it happens that they are more frequently found in secondary propositions. Even the conjunction if may be found in primary propositions. “Men are, if wise, then temperate,” is an example of the kind. It cannot be resolved into “If all men are wise, then all men are temperate.”

4.4.3 As it is not my design to discuss the merits or defects of the ordinary division of propositions, I shall simply remark here, that the principle upon which the present classification is founded is clear and definite in its application, that it involves a real and fundamental distinction in propositions, and that it is of essential importance to the development of a general method of reasoning. Nor does the fact that a primary proposition may be put into a form in which it becomes secondary at all conflict with the views here maintained. For in the case thus supposed, it is not of the things connected together in the primary proposition that any direct account is taken, but only of the proposition itself considered as true or as false.

4.4.4 In the expression both of primary and of secondary propositions, the same symbols, subject, as it will appear, to the same laws, will be employed in this work. The difference between the two cases is a difference not of form but of interpretation. In both cases the actual relation which it is the object of the proposition to express will be denoted by the sign =. In the expression of primary propositions, the members thus connected will usually represent the “terms” of a proposition, or, as they are more particularly designated, its subject and predicate.

4.4.5 To deduce a general method, founded upon the enumeration of possible varieties, for the expression of any class or collection of things, which may constitute a “term” of a Primary Proposition.

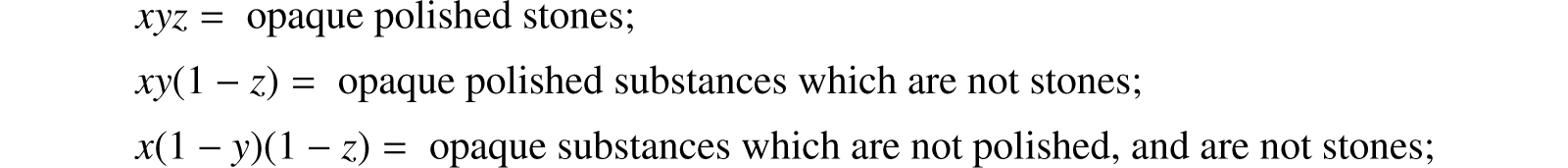

First, If the class or collection of things to be expressed is defined only by names or qualities common to all the individuals of which it consists, its expression will consist of a single term, in which the symbols expressive of those names or qualities will be combined without any connecting sign, as if by the algebraic process of multiplication. Thus, if x represent opaque substances, y polished substances, z stones, we shall have,

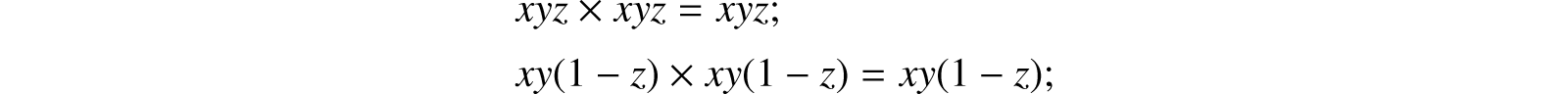

and so on for any other combination. Let it be observed, that each of these expressions satisfies the same law of duality, as the individual symbols which it contains. Thus,

and so on. Any such term as the above we shall designate as a “class term,” because it expresses a class of things by means of the common properties or names of the individual members of such class.

Secondly, If we speak of a collection of things, different portions of which are defined by different properties, names, or attributes, the expressions for those different portions must be separately formed, and then connected by the sign +. But if the collection of which we desire to speak has been formed by excluding from some wider collection a defined portion of its members, the sign − must be prefixed to the symbolical expression of the excluded portion. Respecting the use of these symbols some further observations may be added.

4.4.6 Speaking generally, the symbol + is the equivalent of the conjunctions “and,” “or,” and the symbol −, the equivalent of the preposition “except.” Of the conjunctions “and” and “or,” the former is usually employed when the collection to be described forms the subject, the latter when it forms the predicate, of a proposition. “The scholar and the man of the world desire happiness,” may be taken as an illustration of one of these cases. “Things possessing utility are either productive of pleasure or preventive of pain,” may exemplify the other. Now whenever an expression involving these particles presents itself in a primary proposition, it becomes very important to know whether the groups or classes separated in thought by them are intended to be quite distinct from each other and mutually exclusive, or not. Does the expression, “Scholars and men of the world,” include or exclude those who are both? Does the expression, “Either productive of pleasure or preventive of pain,” include or exclude things which possess both these qualities? I apprehend that in strictness of meaning the conjunctions “and,” “or,” do possess the power of separation or exclusion here referred to; that the formula, “All x’s are either y’s or z’s,” rigorously interpreted, means, “All x’s are either y’s, but not z’s,” or, “z’s but not y’s.” But it must at the same time be admitted, that the jus et norma loquendi seems rather to favour an opposite interpretation. The expression, “Either y’s or z’s,” would generally be understood to include things that are y’s and z’s at the same time, together with things which come under the one, but not the other. Remembering, however, that the symbol + does possess the separating power which has been the subject of discussion, we must resolve any disjunctive expression which may come before us into elements really separated in thought, and then connect their respective expressions by the symbol +.

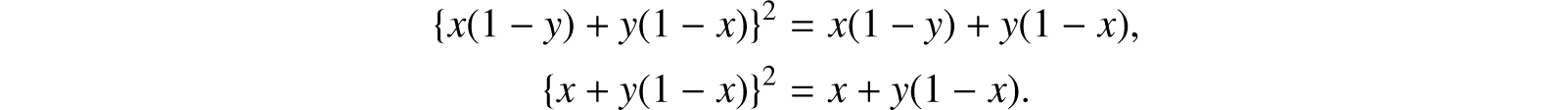

And thus, according to the meaning implied, the expression, “Things which are either x’s or y’s,” will have two different symbolical equivalents. If we mean, “Things which are x’s, but not y’s, or y’s, but not x’s,” the expression will be x(1 − y) + y(1 − x); the symbol x standing for x’s, y for y’s. If, however, we mean, “Things which are either x’s, or, if not x’s, then y’s,” the expression will be x + y(1 − x). This expression supposes the admissibility of things which are both x’s and y’s at the same time. It might more fully be expressed in the form xy + x(1 − y) + y(1 − x); but this expression, on addition of the two first terms, only reproduces the former one.

Let it be observed that the expressions above given satisfy the fundamental law of duality. Thus we have

It will be seen hereafter, that this is but a particular manifestation of a general law of expressions representing “classes or collections of things.” [EDITOR: Original has {x + (1 − x)}2 = x + y(1 − x) for the second equation, apparently in error.]

4.4.7 The results of these investigations may be embodied in the following rule of expression.

RULE.—Express simple names or qualities by the symbols x, y, z, &c., their contraries by 1 − x, 1 − y, 1 − z, &c.; classes of things defined by common names or qualities, by connecting the corresponding symbols as in multiplication; collections of things, consisting of portions different from each other, by connecting the expressions of those portions by the sign +. In particular, let the expression, “Either x’s or y’s,” be expressed by x(1 − y) + y(1 − x), when the classes denoted by x and y are exclusive, by x + y(1 − x) when they are not exclusive. Similarly let the expression, “Either x’s, or y’s, or z’s,” be expressed by x(1 − y)(1 − z) + y(1 − x)(1 − z) + z(1 − x)(1 − y), when the classes denoted by x, y, and z, are designed to be mutually exclusive, by x + y(1 − x) + z(1 − x)(1 − y), when they are not meant to be exclusive, and so on.

4.4.8 On this rule of expression is founded the converse rule of interpretation. Both these will be exemplified with, perhaps, sufficient fulness in the following instances. Omitting for brevity the universal subject “things,” or “beings,” let us assume x = hard, y = elastic, z = metals; and we shall have the following results:

“Non-elastic metals,” will be expressed by z(1 − y);

“Elastic substances with non-elastic metals,” by y + z(1 − y);

“Hard substances, except metals,” by x − z;

“Metallic substances, except those which are neither hard nor elastic,” by

z − z(1 − x)(1 − y), or by z{1 − (1 − x)(1 − y)}.

In the last example, what we had really to express was “Metals, except not hard, not elastic, metals.” Conjunctions used between adjectives are usually superfluous, and, therefore, must not be expressed symbolically.

Thus, “Metals hard and elastic,” is equivalent to “Hard elastic metals,” and expressed by xyz.

Take next the expression, “Hard substances, except those which are metallic and non-elastic, and those which are elastic and non-metallic.” Here the word those means hard substances, so that the expression really means, Hard substances except hard substances, metallic, non-elastic, and hard substances non-metallic, elastic; the word except extending to both the classes which follow it. The complete expression is x −{xz(1 − y) + xy(1 − z)}; or, x − xz(1 − y) − xy(1 − z).

4.5 Of the Fundamental Principles of Symbolical Reasoning, and of the Expansion or Development of Expressions Involving Logical Symbols …

4.5.8 Definition.—Any algebraic expression involving a symbol x is termed a function of x, and may be represented under the abbreviated general form f(x). Any expression involving two symbols, x and y, is similarly termed a function of x and y, and may be represented under the general form f(x, y), and so on for any other case. …

4.5.9 Definition.—Any function f(x), in which x is a logical symbol, or a symbol of quantity susceptible only of the values 0 and 1, is said to be developed, when it is reduced to the form ax + b(1 −x), a and b being so determined as to make the result equivalent to the function from which it was derived.

This definition assumes, that it is possible to represent any function f(x) in the form supposed. The assumption is vindicated in the following Proposition.

4.5.10 To develop any function f(x) in which x is a logical symbol. By the principle which has been asserted in this chapter, it is lawful to treat x as a quantitative symbol, susceptible only of the values 0 and 1.

Assume then, f(x) = ax + b(1 −x), and making x = 1, we have f(1) = a. Again, in the same equation making x = 0, we have f(0) = b. Hence the values of a and b are determined, and substituting them in the first equation, we have

as the development sought. The second member of the equation adequately represents the function f(x), whatever the form of that function may be. …

Reprinted from Boole (1854).