7

A Proposed Automatic Calculating Machine (1937)

Howard Hathaway Aiken

Well into the twentieth century, books of the values of mathematical functions, ten-place logarithms for example, were on the desk of every practicing physical scientist and engineer. Slide rules were useful aids but of limited precision. Electromechanical desk calculators were important machines for the practice of both business and science, but the work of their human operators (mostly women known as “computers”) was tedious in the extreme.

Howard Hathaway Aiken (1900–1973) was a physics professor at Harvard who attained the rank of Commander in the U.S. Naval Reserve. He became a graduate student at Harvard at the age of 33 after working as an engineer for Westinghouse and other companies in the electric industries. In the course of grinding out approximate solutions to equations he needed for his thesis, Aiken tired of doing calculations with the available mechanical calculators and numerical tables. Babbage’s gears and wheels came to his attention and served as an inspiration, though only after he had begun to design his own automatic calculator (Cohen, 1999, p. 67). He seems to have been unaware of the details of Babbage’s design and of Lady Lovelace’s explanation of how it would be programmed, and there is no evidence that he knew anything of Alan Turing’s groundbreaking mathematical work of 1936 or the cryptologic machinery Turing designed during World War II.

This selection is the proposal Aiken submitted for industrial support in constructing the largest electromechanical machine that had ever been built. The Automatic Sequence Controlled Calculator, later dubbed the Mark I, was developed with the assistance of IBM and put into service in 1944. Part of it remains on display at Harvard. Originally some 50 feet long, 8 feet high, and 3 feet deep, weighing nearly 5 tons, it was a marvel of 530 miles of wire, thousands of electromagnetic relays for switches, decimal dials to hold numerical constants, and decimal counters for intermediate storage. Input was punched on card stock; output was printed on an electric typewriter. For decades I walked past this machine almost daily. To pause and examine it is to puzzle over a set of evolutionary dead ends, from the number system to the wiring. The parts are connected by sturdy bell wire, with insulation in unfaded yellow, blue, and red. But rather than bundling different colors together as in modern ribbon cables, so the ends of the same wire could be matched up easily, all the yellow wires in the Mark I are bundled together, as are all the blue and all the red. The bundles are massive, several inches thick, and it is hard today to imagine what purpose the color variation was supposed to serve.

Most importantly, the Mark I’s program was punched into a loop of tape made from the paper stock used for IBM cards. So the machine was designed for repetitive operations, such as summing the terms of a series, but was incapable of executing a recursive algorithm, nested loop, or even, as originally built, a conditional branch. Even in Aiken’s later machines (the Mark IV was the last), there was no concept of a stored program. So while the Mark I was certainly programmable—in the sense that some researchers could prepare new programs while others were using the machine to do useful work—it enjoyed nothing of what we know as software. Aiken’s commitment to what came to be known as the “Harvard architecture”—data and programs in separate kinds of storage—left Aiken’s machines in an intellectual sidetrack. The action moved to other universities and to corporations, and Aiken retired from Harvard at the age of 60.

The Mark I was noisy and clunky, but it worked. Addition or subtraction of 23 decimal digits took 0.3 sec.; multiplication, up to 6 sec.; division, up to 15.6 sec.; log x, ex, or sin x, a minute or more. These speeds were sufficient for the numerical solution of a dozen simultaneous linear equations, an application for which Harvard economist Wassily Leontief used the machine while developing his input–output theory. And Aiken got the last laugh. Most working computers today are in embedded systems, their programs frozen in firmware that cannot accidentally be altered as the machine is running, just like the Mark I’s tape loop.

THE desire to economize time and mental effort in arithmetical computations, and to eliminate human liability to error, is probably as old as the science of arithmetic itself. This desire has led to the design and construction of a variety of aids to calculation, beginning with groups of small objects, such as pebbles, first used loosely, later as counters on ruled boards, and later still as beads mounted on wires fixed in a frame, as in the abacus. This instrument was probably invented by the Semitic races and later adopted in India, whence it spread westward throughout Europe and eastward to China and Japan.

After the development of the abacus, no further advances were made until John Napier devised his numbering rods, or Napier’s Bones, in 1617. Various forms of the Bones appeared, some approaching the beginning of mechanical computation, but it was not until 1642 that Blaise Pascal gave us the first mechanical calculating machine in the sense that the term is used today. The application of his machine was restricted to addition and subtraction, but in 1666 Samuel Morland adapted it to multiplication by repeated additions. [EDITOR: Described in Morland (1673)]

The next advance was made by Leibniz who conceived a multiplying machine in 1671 and finished its construction in 1694. [EDITOR: In fact, it was working by 1674 and still works today.] In the process of designing this machine Leibniz invented two important devices which still occur as components of modern calculating machines today: the stepped reckoner, and the pin wheel.

Meanwhile, following the invention of logarithms by Napier, the slide rule was being developed by Oughtred, John Brown, Coggeshall, Everard, and others. Owing to its low cost and ease of construction, the slide rule received wide recognition from scientific men as early as 1700. Further development has continued up to the present time, with ever increasing application to the solution of scientific problems requiring an accuracy of not more than three or four significant figures, and when the total bulk of the computation is not too great. Particularly in engineering design has the slide rule proved to be an invaluable instrument.

Though the slide rule was widely accepted, at no time, however, did it act as a deterrent to the development of the more precise methods of mechanical computation. Thus we find the names of some of the greatest mathematicians and physicists of all time associated with the development of calculating machinery. Naturally enough, in an effort to devise means of scientific advancement, these men considered mechanical calculation largely from their own point of view. A notable exception was Pascal who invented his calculating machine for the purpose of assisting his father in computations with sums of money. Despite this widespread scientific interest, the development of modern calculating machinery proceeded slowly until the growth of commercial enterprises and the increasing complexity of accounting made mechanical computation an economic necessity. Thus the ideas of the physicists and mathematicians, who foresaw the possibilities and gave the fundamentals, have been turned to excellent purposes, but differing greatly from those for which they were originally intended.

Few calculating machines have been designed strictly for application to scientific investigations, the notable exceptions being those of Charles Babbage and others who followed him. In 1812 Babbage conceived the idea of a calculating machine of a higher type than those previously constructed, to be used for calculating and printing tables of mathematical functions. This machine worked by the method of differences, and was known as a difference engine. Babbage’s first model was made in 1822, and in 1823 the construction of the machine was begun with the aid of a grant from the British Government. The construction was continued until 1833 when state aid was withdrawn after an expenditure of nearly £20 000. At present the machine is in the collection of the Science Museum, South Kensington. …

Since the time of Babbage, the development of calculating machinery has continued at an increasing rate. Key-driven calculators designed for single arithmetical operations such as addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division, have been brought to a high degree of perfection. In large commercial enterprises, however, the volume of accounting work is so great that these machines are no longer adequate in scope.

Hollerith, therefore, returned to the punched card first employed in calculating machinery by Babbage and with it laid the groundwork for the development of tabulating, counting, sorting, and arithmetical machinery such as is now widely utilized in industry. The development of electrical apparatus and technique found application in these machines as manufactured by the International Business Machines Company, until today many of the things Babbage wished to accomplish are being done daily in the accounting offices of industrial enterprises all over the world.

As previously stated, these machines are all designed with a view to special applications to accounting. In every case they are concerned with the four fundamental operations of arithmetic, and not with operations of algebraic character. Their existence, however, makes possible the construction of an automatic calculating machine specially designed for the purposes of the mathematical sciences.

7.1 The Need for More Powerful Calculating Methods in the Mathematical and Physical Sciences

It has already been indicated that the need for mechanical assistance in computation has been felt from the beginning of science, but at present this need is greater than ever before. The intensive development of the mathematical and physical sciences in recent years has included the definition of many new and useful functions, nearly all of which are defined by infinite series or other infinite processes. Most of these are inadequately tabulated and their application to scientific problems is thereby retarded.

The increased accuracy of physical measurement has made necessary more accurate computation in physical theory, and experience has shown that small differences between computed theoretical and experimental results may lead to the discovery of a new physical effect, sometimes of the greatest scientific and industrial importance.

Many of the most recent scientific developments, including such devices as the thermionic vacuum tube, are based on nonlinear effects. Only too often the differential equations designed to represent these physical effects correspond to no previously studied forms, and thus defy all methods available for their integration. The only methods of solution available in such cases are expansions in infinite series and numerical integration. Both these methods involve enormous amounts of computational labor.

The present development of theoretical physics through wave mechanics is based entirely on mathematical concepts and clearly indicates that the future of the physical sciences rests in mathematical reasoning directed by experiment. At present there exist problems beyond our ability to solve, not because of theoretical difficulties, but because of insufficient means of mechanical computation.

In some fields of investigation in the physical sciences as, for instance, in the study of the ionosphere, the mathematical expressions required to represent the phenomena are too long and complicated to write in several lines across a printed page, yet the numerical investigation of such expressions is an absolute necessity to our study of the physics of the upper atmosphere, and on this type of research rests the future of radio communication and television.

These are but a few examples of the computational difficulties with which the physical and mathematical sciences are faced, and to these may be added many others taken from astronomy, the theory of relativity, and even the rapidly growing science of mathematical economy. All these computational difficulties can be removed by the design of suitable automatic calculating machinery.

7.2 Points of Difference between Punched Card Accounting Machinery and Calculating Machinery as Required in the Sciences

The features to be incorporated in calculating machinery specially designed for rapid work on scientific problems, and not to be found in calculating machines as manufactured for accounting purposes, are the following:

1. Ordinary accounting machines are concerned almost entirely with problems of positive numbers, while machines designed for mathematical purposes must be able to handle both positive and negative quantities.

2. For mathematical purposes, calculating machinery should be able to supply and utilize a wide variety of transcendental functions, as the trigonometric functions; elliptic, Bessel, and probability functions; and many others. Fortunately, not all these functions occur in a single computation; therefore a means of changing from one function to another may be designed and the proper flexibility provided.

3. Most of the computations of mathematics, as the calculation of a function by series, the evaluation of a formula, the solution of a differential equation by numerical integration, etc., consist of repetitive processes. Once a process is established it may continue indefinitely until the range of the independent variables is covered, and usually the range of the independent variables may be covered by successive equal steps. For this reason calculating machinery designed for application to the mathematical sciences should be fully automatic in its operation once a process is established.

4. Existing calculating machinery is capable of calculating ϕ(x) as a function of x by steps. Thus, if x is defined in the interval a < x < b and ϕ(x) is obtained from x by a series of arithmetical operations, the existing procedure is to compute step (1) for all values of x in the interval a < x < b. Then step (2) is accomplished for all values of the result of step (1), and so on until ϕ(x) is reached. This process, however, is the reverse of that required in many mathematical operations. Calculating machinery designed for application to the mathematical sciences should be capable of computing lines instead of columns, for very often, as in the numerical solution of a differential equation, the computation of the second value in the computed table of a function depends on the preceding value or values.

Fundamentally, these four features are all that are required to convert existing punched-card calculating machines such as those manufactured by the International Business Machines Company into machines specially adapted to scientific purposes. Because of the greater complexity of scientific problems as compared to accounting problems, the number of arithmetical elements involved would have to be greatly increased.

7.3 Mathematical Operations Which Should Be Included

The mathematical operations which should be included in an automatic calculating machine are:

1. The fundamental operations of arithmetic: addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division

2. Positive and negative numbers

3. Parentheses and brackets: ( ) + ( ), [( ) + ( )] · [( ) + ( )], etc.

4. Powers of numbers: integral, fractional

5. Logarithms: base 10 and all other bases by multiplication

6. Antilogarithms or exponential functions: base 10 and other bases

7. Trigonometric functions

8. Antitrigonometric functions

9. Hyperbolic functions

10. Antihyperbolic functions

11. Superior transcendentals: probability integral, elliptic function, and Bessel function

With the aid of these functions, the processes to be carried out should be:

12. Evaluation of formulae and tabulation of results

13. Computation of series

14. Solution of ordinary differential equations of the first and second order

15. Numerical integration of empirical data

16. Numerical differentiation of empirical data

7.4 The Mathematical Means of Accomplishing the Operations

The following mathematical processes may be made the basis of design of an automatic calculating machine:

1. The fundamental arithmetical operations require no comment, as they are already available, save that all the other operations must eventually be reduced to these in order that a mechanical device may be utilized.

2. Fortunately the algebra of positive and negative signs is extremely simple. In any case only two possibilities are offered. Later on it will be shown that these signs may be treated as numbers for the purposes of mechanical calculation.

3. The use of parentheses and brackets in writing a formula requires that the computation must proceed piecewise. Thus, a portion of the result is obtained and must be held pending the determination of some other portion, and so on. This means that a calculating machine must be equipped with means of temporarily storing numbers until they are required for further use. Such means are available in counters.

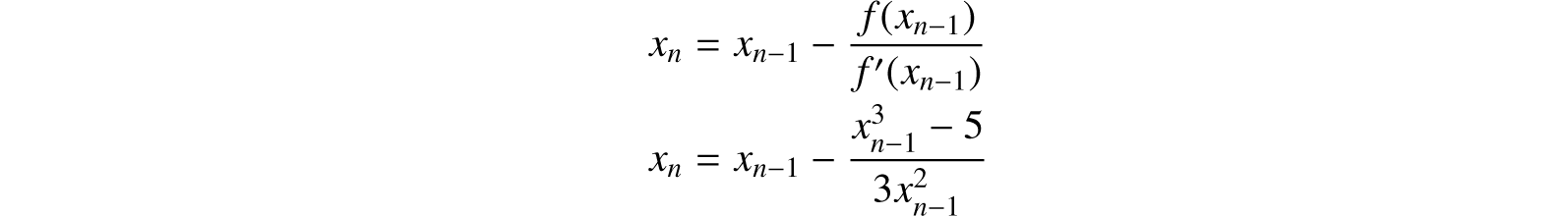

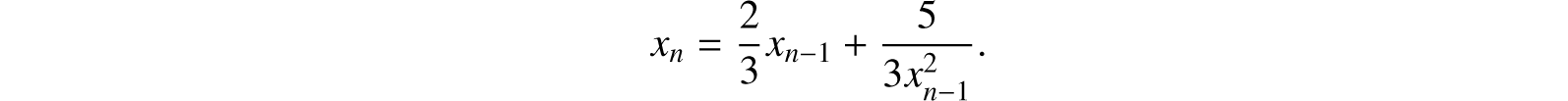

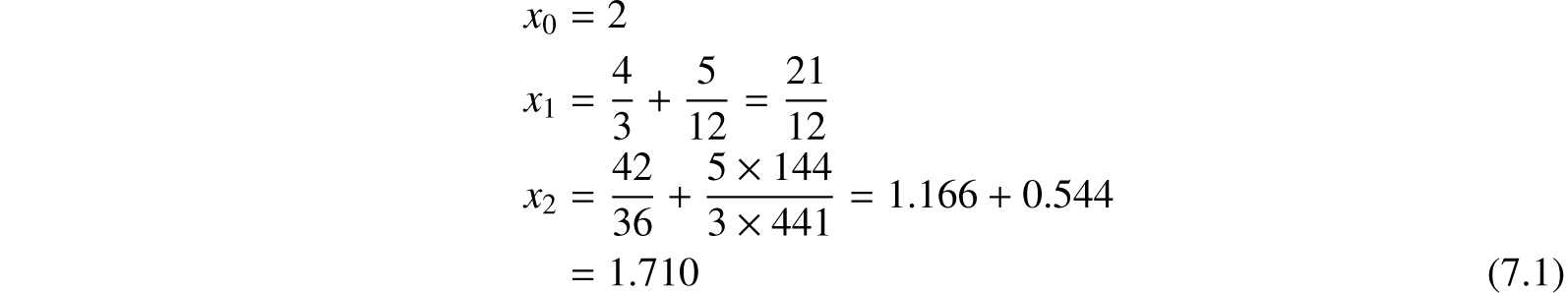

4. Integral powers of numbers may be obtained by successive multiplication, and fractional powers by the method of iteration. Thus, if it is required to find 51/3,

and

or

Let

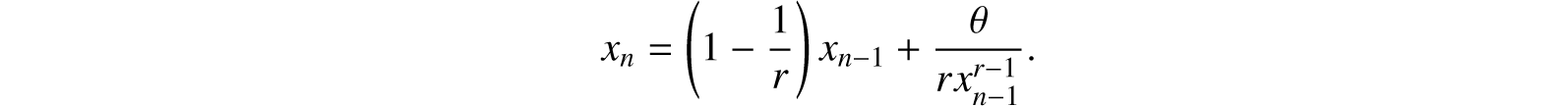

which is the cube root of 5 to four significant figures. In general the rth root of θ is given by the iteration of the expression

Finally, if r is not an integer, recourse may be had to the mechanical table of logarithms later to be described. …

16. The numerical integration of empirical data may be carried out by the rules of Simpson, Weddle, Gauss, and others. All these rules involve sums of successive values of y multiplied by specified numerical coefficients. Hence the only new mechanical component involved is a means of mechanically introducing a list of numbers. Means of accomplishing this will be discussed later.

17. Numerical differentiation of empirical data is best accomplished by means of a difference formula. Most experimental observations are of such an accuracy that fifth differences may be neglected by taking observations sufficiently close together. If, then, all differences above the fifth may be neglected, the process of numerical differentiation may be carried out by a fifth difference engine such as originally designed by Babbage. Such a device can, however, be assembled from standard addition-subtraction machines with but a few changes. The differentiating apparatus would also be applicable to many other problems. In fact, most of the problems already discussed may under certain circumstances be solved by application of difference formulae.

7.5 Mechanical Considerations

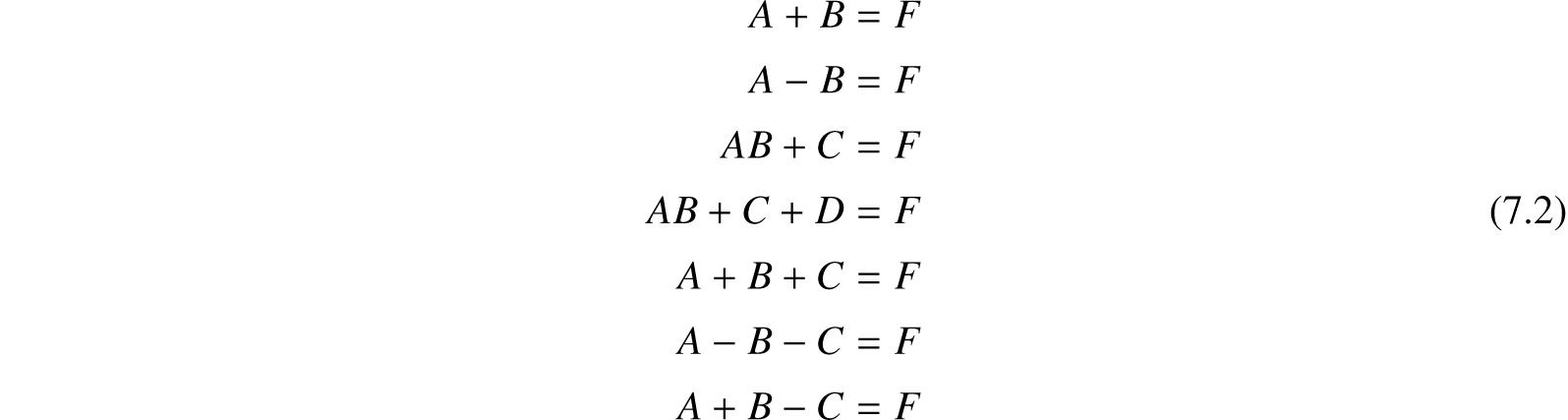

In the last section it was shown that even complicated mathematical operations may be reduced to a repetitive process involving the fundamental rules of arithmetic. At present the calculating machines of the International Business Machines Company are capable of carrying out such operations as:

In these equations A, B, C, D are tabulations of numbers on punched cards, and F, the result, is also obtained through punched cards. The F cards may then be put through another machine and printed or utilized as A, B, …, cards in another computation.

Changing a given machine from any of the operations (7.2) to any other is accomplished by means of electrical wiring on a plug board. In the hands of a skilled operator such changes can be made in a few minutes.

No further effort will be made here to describe the mechanism of the IBM machines. Suffice it to say that all the operations described in the last section can be accomplished by these existing machines when equipped with suitable controls, and assembled in sufficient number. The whole problem of design of an automatic calculating machine suitable for mathematical operations is thus reduced to a problem of suitable control design, and even this problem has been solved for simple arithmetical operations.

The main features of the specialized controls are machine switching and replacement of the punched cards by continuous perforated tapes. In order that the switching sequence can be changed quickly to any possible sequence, the switching mechanism should itself utilize a paper tape control in which mathematical formulae may be represented by suitable disposed perforations.

7.6 Present Conceptions of the Apparatus

At present the automatic calculator is visualized as a switchboard on which are mounted various pieces of calculating machine apparatus. Each panel of the switchboard is given over to definite mathematical operations.

The following is a rough outline of the apparatus required:

1. IBM machines utilize two electric potentials: 120 volts ac for motor operation, and 32 volts dc for relay operation, etc. A main power supply panel would have to be provided including control for a 110-volt-ac/32-volt-dc motor generator and adequate fuse protection for all circuits.

2. Master control panel: The purpose of this control is to route the flow of numbers through the machines and to start operation. The processes involved are: (a) Deliver the number in position (x) to position (y); and (b) start the operation for which position (y) is intended. The master control must itself be subject to interlocking to prevent the attempt to remove a number before its value is determined, or to begin a second operation in position (y) before a previous operation is finished.

It would be desirable to have four such master controls, each capable of controlling the entire machine or any of its parts. Thus, for complicated problems the entire resources could be thrown together; for simpler problems fewer resources are required and several problems could be in progress at the same time.

3. The progress of the independent variable in any calculation would go forward by equal steps subject to manual readjustment for change in the increment. The easiest way to obtain such an arithmetical sequence is to supply a first value, x0, to an adding machine, together with an increment Δx. Then successive additions of Δx will give the sequence desired.

There should be four such independent variable devices in order to (a) calculate formulae involving four variables; and (b) operate four master controls independently.

4. Certain constants: many mathematical formulae involve certain constants such as e, π, log10 e, and so forth. These constants should be permanently installed and available at all times.

5. Mathematical formulae nearly always involve constant quantities. In the computation of a formula as a function of an independent variable these constants are used over and over again. Hence the machine should be supplied with 24 adjustable number positions for these constants.

6. In the evaluation of infinite series the number 24 might be greatly exceeded. To take care of this case it should be possible to introduce specific values by means of a perforated tape, the successive values being supplied by moving the tape ahead one position. Two such devices should be supplied.

7. The introduction of empirical data for nonrepetitive operations can be accomplished best by standard punched-card magazine feed. One such device should be supplied.

8. At various stages of a computation involving parentheses and brackets it may be necessary to hold a part of the result pending the computation of some other part. If results are held in the calculating units, these elements are not available for carrying out succeeding steps. Therefore it is necessary that numbers may be removed from the calculating units and temporarily stored in storage positions. Twelve such positions should be available.

9. The fundamental operations of arithmetic may be carried on three machines: addition and subtraction, multiplication, and division. Four units of each should be supplied in addition to those directly associated with the transcendental functions.

10. The permanently installed mathematical functions should include: logarithms, antilogarithms, sines, cosines, inverse sines, and inverse tangents.

11. Two units for MacLauren series expansion of other functions as needed.

12. In order to carry out the process of differentiation and integration on empirical data, adding and subtracting accumulators should be provided sufficient to compute out to fifth differences.

13. All results should be printed, punched in paper tapes, or in cards, at will. Final results would be printed. Intermediate results would be punched in preparation for further calculations.

It is believed that the apparatus just enumerated, controlled by automatic switching, should care for most of the problems encountered.

7.7 Probable Speed of Computation

An idea of the speed attained by the IBM machines can be had from the following tabulation of multiplication in which 2 × 8 refers to the multiplication of an 8 significant figure number by a 2 significant figure number, zeros not counted (Figure 7.1).

Figure 7.1: Expected multiplication speed

In the computation of 10 place logarithms the average speed would be about 90 per hour. If all the 10-place logarithms of the natural numbers from 1000 to 100,000 were required, the time of computation would be approximately 1100 hours, or 50 days, allowing no time for addition or printing. This is justified since these operations are extremely rapid and can be carried out during the multiplying time.

7.8 Suggested Accuracy

Ten significant figures have been used in the above examples. If all numbers were to be given to this accuracy it would be necessary to provide 23 number positions on most of the computing components, 10 to the left of the decimal point, 12 to the right, and one for plus and minus. Of the twelve to the right, two would be guard places and thrown away.

7.9 Ease of Publication of Results

As already mentioned, all computed results would be printed in tabular form. By means of photolithography these results could be printed directly without type setting or proof reading. Not only does this indicate a great saving in the publishing of mathematical functions, but it also eliminates many possibilities of error.

Reprinted from Aiken et al. (1964), with permission from the Harvard University Archives.