Sagittari Nervi

From his mouth came a two edged sword ready to smite the nations.

Revelations 19:15

Diocletian was determined to reorganize the army.1 The legions with their six thousand heavy infantry were too cumbersome to deal with guerrilla warfare by barbarian invaders. Auxiliary cohorts of five hundred men on too many occasions had been overrun. A political motive was involved as well. The legions repeatedly had used their strength to overthrow the throne. Therefore, Diocletian formed many new-style legions, each of one thousand men.2

The army was divided into two types of units by Diocletian’s reforms: the numeri, local defence forces, and the field army that actively moved about the Empire’s frontier, the comitati. The word literally meant those who ate together, i.e., live in barracks, ancestor to the word ‘committee’. The changes were flawed. The numeri would tend to be lax, reluctant to defend any area other than their locale. Many units were each of one ethnic group. The previous system had integrated legionnaires of every ethnic origin, transferring them repeatedly to units throughout the Empire. This had inspired an imperial loyalty and high morale. The new policy undermined it.

One of the strongest arguments against the truth of the legend of the Theban Legion was that Roman authorities would not have annihilated an entire old-style legion. The Acts are quite clear that the Thebans numbered about six thousand.

Voltaire in the eighteenth century believed the legend of the Theban Legion to be nonsense. He knew nothing, apparently, of the surviving Roman army list, the Notitia Dignitatum.

The Notitia Dignitatum lists hundreds of units with their duty stations and their individual shields. It records four Legio Thebeorum.3 Three are the only legions bearing the names of Diocletian and his viceroys, the I Maximiana Thebeorum,4 II Flavia Constantia Thebeorum5 and III Diocletiana Thebeorum.6 Their consecutive listing and numbering gives evidence that they were a series.

The Act of Maximilian describes him as the son of a centurion, and therefore eligible to directly enter the army as an officer. Diocletian’s new policy demanded that he enter the army. In 295, in North Africa, he was brought before a judge for refusing military service. The pagan official is depicted as not hostile to the youth’s Christianity but anxious to save Maximilian’s life. Maximilian had tossed away his military seal, the lead identification tag worn around the neck. He refers to another seal, undoubtedly his baptism. He was to be an officer and therefore required to take the military oath.

‘I will not accept the seal,’ he replied. ‘I already have the seal of Christ who is my God.’

The judge attempted to make a strong point in rebuttal.

The proconsul Dion said: ‘In the sacred bodyguard of our Lords Diocletian and Maximian, Constantius and Maximus (Galerius), there are soldiers who are Christians, and they serve.’

Maximilian replied: ‘They know what is best for them. But I am a Christian and can do no wrong.’7

The Act of Maximilian cites the bodyguard units of the tetrarchs to be Christian. These by all logic must be the Thebeorum units cited above.

These three units must have been created with a unit later missing from the Notitia Dignitatum carrying the name of Galerius, the fourth tetrarch. Becoming a challenger of those succeeding to the emperor’s throne, presumably his name was dropped from the unit title. Thus Legio I Flavia Constantia, which shares its shield design with II Flavia Constantia Thebeorum, was originally IV Galeriana Thebeorum.

The Theban Legion was never annihilated. Staff and enlisted men of its headquarters company were martyred and the legion reorganized into the four bodyguard units of the tetrarchs plus two other units.

Most emperors had been killed by their bodyguards. The Thebans had not used violence even in self-defence against their persecutors. The effort would have brought persecution. The worst critics of Christians never accused them of involvement in coups.

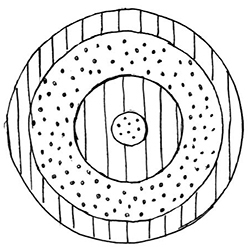

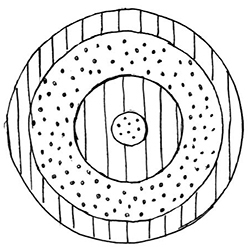

That the first of the bodyguard units was named for Maximian supports the Theban legend. Two other units have the same shield design as the I and II Flavia Constantia.8 These are the Sagittari Nervi9 and the Leones Seniores.10 Both were Saxon Shore units, the Nervi composed of archers. The Leones were from Leon in Asturias, Spain. These four are the only identical shields of hundreds in the Notitia Dignitatum. The six together had as many men as an old-style legion. The persecutors were to trust their lives to those they persecuted.

The Swiss scholar Van Berchem has argued that the legend of the Theban Legion is false,11 based on a misunderstanding arising from the transfer to the Alps of the cult of a Mauricius, a tribune put to death with seventy of his men at Apameia, (Homs) Syria, when Galerius passed through that town on a campaign versus Persia. This must have been in 297. But Mauricius of Apameia12 and his circle died of thirst, exposure and the bites of scorpions after being tied to palm trees. The military rank he possessed was different from that of Mauricius of Acaunus and his Act makes no mention of Thebans. Moreover, the names of the officers accompanying him are entirely different than those of the Thebans at Acaunus. His son was crucified, an event not in the Theban legend.13

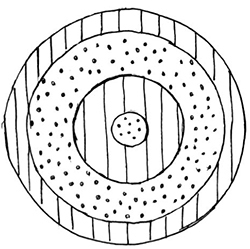

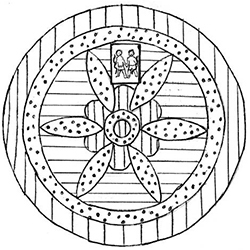

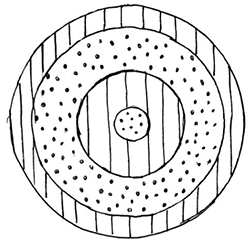

The Shields of the Six Smaller Units Formed from the Original Theban Legion

Sagittari Nervi

Leones Seniores

Two Saxon Shore Units

Blue

Yellow

Red

I Maximiana Thebeorum

II Flavia Constantia Thebeorum

III Diocletiana Thebeorum

I Flavia Constantia (IV Galeriana Thebeorum)

The four Theban bodyguard units of the Tetrarchy

Galerius began his eastern campaign with his forces caught while crossing the Euphrates and the vanguard badly mauled. Diocletian was so annoyed that he had Galerius run alongside his chariot in humiliation before the army. Galerius was a former wagon driver with a vocabulary suited to the task. Massive and red faced, he had a short temper and a brooding hostility towards those who offended him.14

On this campaign against Persia the emperor employed a troop of barbarian cavalry, Sarmatians and Slavs from the great plains north of the Black Sea. The two chief officers of this unit, the Schola Gentilum, the ‘band of foreigners’, were Sergius and Bacchus.15 They had the rare honour of being ‘friends of caesar’, a legal rank that allowed them to initiate conversation with the emperor. To Diocletian’s dismay, he discovered that both were Christians who refused to worship the idols or take the military oath. Their punishment was to be dressed in women’s clothes and forced to run for many miles alongside Galerius’ chariot. Thereafter, one was beheaded and the other clubbed to death.

A manuscript by Coptic Christians, the so-called cycle of Basilides,16 describes events of these years that are not found in Latin and Greek accounts. Not translated until the twentieth century, it has the appearances of a romantic novel, with Basilides the kinsman or friend of the many individual martyrs in the tale. It contains no claims of the miraculous and emphasizes Christian military insubordination and international policy independent of both the Roman and Persian imperial governments. This may have made it an embarrassment to churchmen under Christian emperors, if they knew of it.

After a successful Persian campaign about late 297, Galerius returned to Antioch with hostages. According to the Coptic account, he discovered officers openly preaching Christianity to their troops. A Persian prince, Nicomedes,17 a hostage allowed to reside at the home of the archbiship of Antioch, escaped. Another hostage, the general Banikarous, had been baptized.

Diocletian demanded that his officers worship the idols. Claudius the Stratelates or general, Justus, Leontius the Syrian, Theodore the Oriental (Armenian) and Anatole the Persian refused. Anatole, a man with high-ranking relatives in the Persian Empire, had been fifteen years in the Roman army.18 In other words, he entered in 282, the year that Probus had set his project for a Theban Legion into motion.

Hearing of this, the troops of Leontius19 and Theodore on the River Atoush near Lake Van in the satellite realm of Armenia baptized themselves by the hundreds. Neither bishops nor clergy are mentioned in this action. Diocletian’s order to evacuate Armenia in keeping with his treaty with the Shah Narses was disobeyed by these troops, who may have feared to expose Armenian Christians to Persian persecution. Diocletian was moving to declaring Christianity illegal but Armenia as a satellite kingdom, strictly speaking, was not within his Empire.

Diocletian was readily convinced at this point that Armenian nationalists and Christians were conspiring against him. He was aided in this view by the staff officer Veturius20 and the neo-platonist philosopher Theotecnus21 whose writings provided the ideological justification for persecution that appealed to Diocletian’s intellectual bent.

Eusebius states that a plan was conceived to purge the army of Christians.22 All were offered immediate discharge, apparently with no loss of pension or veterans’ privileges. Those remaining were demoted. None were allowed to be officers. Considering that there may have been pagans glad to receive early discharge before their twenty-five years were completed, this policy could appear to reward Christians for being undesirables. It was a deceit in order to attack those released once they were disarmed and unorganized.

About 298 the troops of Leontius and Andrew in Armenia, according to the Coptic accounts, were no longer invited to retire but ordered to do so. Galerius was instructed to kill them when they arrived on Roman soil. Himes23 and Philkiades, kinsmen of some of these murdered dischargees, in revenge pulled Diocletian from his horse as he rode through the streets of a town and were killed. For Diocletian, this was full justification for persecution. At Antioch, 2,000 troops led by Fasilidas (Basilides)24 and 900 led by Anderuna (Andrew) were martyred. Martyr in Greek literally meant witness. Those who survived loss of property, demotion, jail or torture were considered living ‘white’ martyrs. Not every martyr was necessarily executed. In Cappadocia, Agapitus25 legally quit the army and was harassed and imprisoned. He survived to become a bishop and die a natural death. Gordius26 and Seleucus, likewise, retired but their bold admission of faith incurred their executions.

The most famous of soldier saints is George. Miracles and deaths by hideous tortures and as many resurrections abound in the Coptic narratives regarding him, tales that make his dragon-killing pale in comparison. He is not in the Basilides cycle. George’s fantasies in 485 were formally condemned by Pope Gelasius and a council of bishops as ‘false and unedifying’.27 Sifting through the Coptic account, objective data are to be found, nonetheless, which stand out from the lurid material, suggesting the hand of a different writer than the pious fantasist. George is declared to have been the son of Anastasius, governor of Melitene, Cappadocia. The account makes no mention of it but this was headquarters of Legio XII Fulminata, the ‘Christian legion’. His grandfather had been John, governor of Cappadocia. Justus, the new governor and father of George’s fiancée, appointed him commander of 5,000 men, presumably Legio XII Fulminata. Upon Justus’ death, George went to Tyre to ask to be confirmed in his father’s rank. Possibly he was seeking a civilian rank in order to evade the army purge of Christians not yet extended to civil offices.

Arriving at Tyre, George found Dadianus (Tatian?) and his officers worshipping Apollo. He left, distributed his goods among the poor, released all but his closest servants and returned to confront Dadianus. Refusing to honour the gods, he was tortured and killed. Some 3,000 of his soldiers were martyrs, either ‘red’ and executed or ‘white’, harassed but surviving. Eusebius stated that outright revolt broke out at Melitene under Diocletian’s persecution, the only revolt by Christians he records.28 He gives no details, consistently ignoring the military martyrs.

The effort to oust Christians from the army in its treachery encouraged Christians who were secretly in the army to remain.

Soldiers directly refusing idolatry were not offered an option to quit. In Spain at Leon, the fortress that had sent troops to the Leones Seniores associated by its shield with the Theban Legion, the centurion Marcellus29 had been baptized with all his family. Possibly he was a veteran who was later recalled. Sent to Tangiers, North Africa, and a detachment of II Traiana, he refused the military oath. The governor ignored it. In October of 298, in the presence of visiting high officials on the anniversary of Maximian’s birth, he refused to sacrifice to Hercules and threw down the belt that was the symbol of his office. He was beheaded. Later in Spain more than ten of his sons or godsons were slain.

Eusebius, without mentioning any units by title, wrote that in 298 he had encountered Constantine, the son of Constantius Chlorus, as tribune of Galerius’ bodyguard in the Middle East.30 In context of the Acta Maximiliani and the Notitia Dignitatum, this means that Constantine began his army career as an officer of survivors of the Theban Legion.

Embarking for Egypt, Diocletian took Claudius31 and Justus and their families with him as prisoners. The Egyptian soldier Hor32 and his brother Bhai, ‘having left Antioch’, were martyred at this time in Alexandria under Diocletian as was John33, a soldier ‘of the emperor’s cohort’, sent from Antioch. An official papyrus proves that Diocletian’s bodyguard, Legio III Diocletiana Thebeorum, was present in Egypt by 300.34

In Egypt, Diocletian initiated his reorganization of the Roman world into a rigid totalitarianism, Egypt the property of the emperor unhindered by the Senate.

The legionnaires of Egypt sent elsewhere had been replaced by European troops to avert the army joining with the peasants in opposition to the new laws. Meanwhile, Christianity was accelerating among the population, the Bible translated into the Coptic language appearing in the decade,35 written not on scrolls but in bound books.

As the bagaudae had taken to the forests and meadows in the West, in Egypt thousands of men fled into the desert to escape the increasing oppression. They became hermits and beggars called anchorites, in Greek, ‘those who ran away’.36 The Copts had been a virtual caste society for thousands of years. They had revolted on countless occasions with grim results. But revolt is not revolution. Revolution requires a change in mentality, a new philosophy. The Coptic peasantry had never had this until Christianity offered it to them.

They did not seek violence.37 Their defiance was thrust upon them, their courage that of peaceful folk, yet it threatened to become a profound upheaval, alarming the government.

Diocletian’s perspectives were military, his understanding of economics meagre. In this he was no worse than other thinkers of his day.

Many cities of the East had issued their own coinage alongside the imperial issue, competing in the value of their coinage by avoiding overproduction. Imperial abolition of these local issues in 260 provoked catastrophic inflation as the government, short of silver, debased the coinage with cheaper metal. Deliberate scarcity offered more profit than increased production amidst inflation. Farmers had less incentive to sell with buying power reduced. Estate owners established workshops on their villas to avoid the high prices of city goods as craftsmen fled the high taxes of the cities. Civilization was coming apart. The government, in repairing a system that worked, however inefficiently, was wrecking it.

Diocletian’s solution was drastic. All prices and wages were fixed by the government in 303.38 Marketplace stone walls survive inscribed with Diocletian’s prices and wages. Despite the death penalty for violation, the effort quickly failed. It made some goods so underpriced that producers lowered production.

To support the enlargement of the army Diocletian introduced a new system of recruitment.39 Previously, all soldiers were volunteers with the very rare exceptions of conscriptions in emergencies. The new system demanded landlords and villages provide draftees for the army. It should have been foreseeable that these recruits tended to be people considered good riddance.

The army’s numbers increased with the crushing taxes to support them as the economy crumbled. To make matters worse, Diocletian experimented with the conscription of slaves, criminals, gladiators and prisoners of war. The effect on the morale of men of these backgrounds forced into twenty-five years’ service should have been obvious but Diocletian’s underlings habitually told him what they thought he wished to hear. Roman practicality had become expediency.

In Egypt, in the transition after traditional army units were withdrawn to be replaced by European units, military camps were undermanned, an invitation to revolt.

Alexandria alone had been allowed to continue issuing its own coinage despite the reforms of 260. The abolition of its coinage in 296 had the effect of a high temporary tax as the old money was exchanged for new. Many businessmen were ruined. In response, the director of Alexandria’s mint, Domitius Domitianus,40 known as Achilleus, led the city in revolt and declared himself emperor.

At the same time, farmers upriver, squeezed by landlords living in Alexandria who tried to save themselves at the expense of their tenants, also revolted. Egypt was soon in chaos. Diocletian crushed the revolt in the metropolis seven months after it began. The towns of Busiris and Coptos in southern Egypt were burned to the ground with a savagery rare in Roman warfare, which usually respected Roman towns, the very purpose and justification for Roman rule.

In the army and outside it, many oppressed people had no rallying point, common creed or trust except the Church. Political revolt was given religious ardour by Diocletian’s self-defeating intolerance and persecution, yet Christian scribes would ignore any issues involved except religion. History of these events would thus be distorted for ages.