5 The fourteenth century

Although a famous popular history book's subtitle glossed the fourteenth century as ‘calamitous’, a consideration of its music would probably see the period as a triumph. 1 In part this is because the chief technology that gives us access to the past – writing – became more widely used for record keeping by this time. In particular, the special kind of writing used to record musical sounds – musical notation – reached a new level of prescription, describing relative pitches and rhythms more fully than before. As the fourteenth century paid more cultural attention to writing things down in the first place, more music books survive from this period than from any earlier centuries, and their contents seem tantalizingly decipherable.

The detailed social and political history of the fourteenth century is complex and beyond the scope of this chapter. However, some of its aspects will be mentioned here, not in order to give a comprehensive history, but in order to suggest ways in which larger historical changes affected musical culture.

The later fourteenth century saw a deep division of the Western Christian church, a problem partly caused by the refusal of successive popes to reside in Rome after the French pope Clement V moved the papal court to Avignon (France) in 1309. The often lavish papal court was responsible for employing a large number of expert singers, many of whom we know to have also been composers because pieces by them survive. 2 Avignon was especially important as a centre for musical activity during the reign of the ‘humanist’ pope Clement VI (b.1291–2, elected 1342, d.1352), whose circle included the music theorist and scientist Johannes de Muris, as well as the composer Philippe de Vitry, whom several later writers saw as key in the practical deployment of the new notational style of the Ars Nova within motets and secular songs. 3 Despite Avignon's status as an ecclesiastical court, musical activity there included the composition and performance not only of sacred music, but also of secular songs and political motets. Vitry's motet Petre Clemens / Lugentium siccentur , for instance, was written for the visit to Avignon in January 1343 of the Ambassadors of the Roman citizens, who tried (unsuccessfully) to tempt the newly elected Clement VI back to Rome. 4 The balades Courtois et sages (by Magister Egidius), Par les bons (by Philippus de Caserta) and Inclite flos (by Matteus de Sante Johanne) were all written for the Avignon ‘anti-pope’ Clement VII (1378–94), whose election initiated the Western schism that dominated the church until its resolution at the Council of Constance in 1417. In 1378 Gregory XI returned the papacy to Rome, dying there shortly after his arrival. Under threat of violence from the citizens of Rome, the cardinals – including the future anti-pope Clement VII (Robert of Geneva) – elected the Italian archbishop Bartolomeo Prignano of Bari as Pope Urban VI on 8 April 1378. Five months later, however, under the pretext that election under such duress was invalid, another election saw Robert himself elected, acknowledged by Aragon, Castile, Denmark, France, Navarre, Norway, Portugal, Savoy, Scotland and some German states. 5 The Italians continued to support Urban VI; Clement VII returned his papal court to Avignon. Two (and later three) popes then reigned simultaneously until the church was reunified with the election of Martin V in 1417, who finally and unequivocally returned the papacy to Rome.

The fourteenth century also saw much of the so-called Hundred Years War (actually a series of conflicts lasting from roughly 1337 to 1453) between England and France. 6 Although war might be thought a negative influence on culture, medieval warfare differed from modern warfare in scale and process, allowing a far greater role for ceremonial, parleys and other forums. At one point the French king and his entire court were in captivity in England, where they engaged in courtly activities – hunting and performances of poetry and music – similar to those they would have undertaken at home. Music and musicians played important roles in international diplomacy and propaganda. 7

The schism and war were not the only factors that fed an ever-present late-medieval eschatology – a preoccupation with the Last Things and the Day of Judgement. A European population that since 1250 had expanded to levels not seen again in some states until the middle of the nineteenth century was struck first by a serious famine (1315–22) and then by epidemic disease. 8 The first large-scale occurrence of the so-called Black Death, which contemporaries referred to as the ‘Great Mortality’, swept Europe between 1347 and 1350, killing an estimated one third of the population. 9 On the other hand the size of court retinues continued to rise during this period, with noblemen and princes employing ever more functionaries. 10 Such large retinues could not be paid merely in kind (with food, lodging, clothes and so on), but required monetary salaries and pensions, accounts of which were more carefully kept than before (in turn necessitating the service of increased numbers of literate clerks, who were often also chapel functionaries). 11 The increase in households and courts saw a concomitant increase in the number of musicians, singers and scribes employed (not least in the capacity of secretary, a post held by the poet-composer Guillaume de Machaut at the court of Jean of Luxembourg, for example). As mentioned above, the rise in the levels of record keeping also affected the amount of music written down.

The other cultural change that affected music in the fourteenth century was bound up with music's continued place within the basic university training of the Middle Ages, the arts degree. 12 Musica – a subject whose definition encompassed far more than just sounding music in performance – was one of the mathematical subjects of the quadrivium. The fourteenth century witnessed a revolution in mathematical thinking which broadly shifted from an arithmetical mathematics based on fixed points and which sharply distinguished qualities from quantities, to a geometric mathematics based on movement and allowing for the quantification of quality through estimation and approximation. 13 It seems likely that this had some impact on the conceptual changes in the basis of musical notation, especially as one of the chief music theorists, Johannes de Muris, also wrote on advanced mathematics. 14 Music also received a boost that connected university and court in the shape of the translation of Aristotle's Politics from its late-thirteenth-century Latin version into French by Nicole Oresme. 15 Book VIII argues strongly for music's propriety for noblemen not just as an abstract intellectual discipline (as Boethius's treatise implies) but as a leisured pursuit and appropriate for relaxation.

The fourteenth century is often discussed in terms of the rise of the composer; it certainly is the case that we know the names of more composers from this period than from previous centuries, and importantly we know the names of composers of polyphonic music, in stark contrast to the general situation with the polyphony of the thirteenth century. However, the manuscripts of troubadour and trouvère song are often organized by composer, a trait that can be seen as late as the retrospective anthology of trecento song in the Squarcialupi Codex. And we know the names of those who put together (componere ) chant offices for local saints from as early as the tenth century. 16 It can be seen that musicology has tended to make ‘composer’ stand for ‘composer of polyphony’ in a way that is one of many aspects of medieval studies that say more about the preoccupations of latter-day musicologists than about the Middle Ages. 17

Motets

Certain forms in use in the thirteenth century continued to flourish in the fourteenth. The motet in particular retained its importance, but where formerly whole collections were dedicated to it, in the fourteenth century motets tend instead to be copied within song collections, indicating their migration even further from the liturgical sphere. The formal developments in motet composition in fourteenth-century France – the main place where the form was cultivated – show a reduction from the variety of types practised in the thirteenth century but a greater variety within the remaining type than was explored hitherto. 18 The tenor is a numerical scheme underlying the whole piece and is rhythmically differentiated from the much faster-moving top voices. The uppermost voice – the triplum – moves fastest of all, the motetus a bit slower, and the rigidly patterned tenor slowest of all. The tenor patterns of pitch (color ) and rhythm (talea ) can be coterminous or can overlap. 19 The new numerical possibilities of the motet lent themselves to the exploration of numerical symbolism and other inaudible but meaningful features. 20 The large five-section motet Rota versatilis , composed in England before 1320, has sections in the proportions 12:8:4:9:6, which symbolize the fundamental musical proportions commonly found in elementary music theory, where they are said to have been discovered by Pythagoras. 21

Whether or not the upper voices reflect the patterning of the tenor varies. Scholars have traditionally seen a movement from having barely any reflection of the tenor in the upper voices (as in most thirteenth-century motets from the old corpus of Montpellier, for example), to what has been termed ‘pan-isorhythm’, where the tenor's repeating structure is reflected in all the upper parts. Perhaps composers experienced an increased need to articulate the motet's structure in this readily audible way when its sheer scale expanded to the grand proportions of the fourteenth century. The net effect was that the motet became almost strophic in form.

The upper voices of the fourteenth-century motet began to adopt regular versification, in contrast to the more playful rhymes and metrical schemes which typify the upper voices of earlier motets. The polytextuality of the upper voices continued, and the possibility for intertextual play between each upper voice and both with the tenor was expanded as composers exercised a freer choice of tenor melismas, no longer restricting their choice to those clausula-derived segments of chant that typically group the thirteenth-century motet into tenor families. Machaut, for example, chooses short emblematic words from chants that are not used as the basis for motets at all in the thirteenth century. 22 This freedom of authorial choice probably reflects a complete disengagement of the performance situation of motets from liturgical or para-liturgical use and their newer association with courtly activities. However, this does not necessarily remove the intertextual resonance of the liturgical situation ‘cued’ by the tenor; as with thirteenth-century motets, those of the fourteenth century can be read as exploring analogical overlap (and difference) between devotional practices of different kinds (sacred and courtly-secular). 23 The situation with English motets differs in this respect from the French repertory. Although most of the 100 or so motets, mainly in three parts with two upper voices texted in Latin, that survive from early-fourteenth-century England are fragmentary, they not only show a far greater formal variety than the French motets of the period but often have more explicitly devotional upper-voice texts. 24

Songs

Arguably the most important musical innovations of the fourteenth century occurred in the field of secular song. The combination of polyphonic musical textures with a number of refrain forms, known today as the formes fixes , whose texts were predominantly high-style courtly poetry, at once broke with the types of song current in the thirteenth century (in which courtly refrain forms tended to be courtly-popular danced poems, high-style poems tended to lack refrains, and neither were polyphonic) and set a standard for the next century and a half. 25 The overwhelming presence attested by the sources is that of Guillaume de Machaut, a major French poet for whom music-writing – especially as facilitated and made precise by the new notation of the Ars Nova – was just a further element in the performance of his poetry over which he could exert his considerable authorial control.

Machaut's thematization of himself as an author, as a controlling presence behind his book, in conjunction with his own training as a secretary and his interest in making books, mean that the source situation for this composer is strongly atypical. His works are preserved in no fewer than six large manuscripts from the second half of the century, that are dedicated entirely to them. A few of his musical works also crop up in other songbooks, and his lyrics and narrative poems also appear in other text-only poetry sources. Nevertheless, the weight of authority that accrues to the six so-called Machaut manuscripts is powerful: it enables us to trace a life and works for this composer far more detailed than those of any of his contemporaries. By contrast, his equally famous colleague Philippe de Vitry – a poet-composer perhaps better regarded by those contemporaries who rated their own learning – has no such ‘collected works’ source. Vitry's works are transmitted in the way in which musical works of this period are generally found: in collections of pieces by a number of different composers, often anonymous, and without the extreme care in presentation that we find in Machaut's richly illuminated books. Although we have a number of motets that can be linked with Vitry, unless they are contained in the interpolated version of the poem Fauvel found in F-Pn fr. 146, his notated songs are lost. We have only the word of the anonymous author of a poetry treatise dating from 1405–32 that Vitry ‘invented’ the writing of balades, lais, and simple rondeaux. 26

Rondels to rondeaux

Of the formes fixes , the one that most clearly carries on a form present in the thirteenth century is the rondeau. Musically, the rondeau is perhaps the simplest of the fixed forms as it has two musical sections of roughly equal length. These sections A and B are sung in the pattern AB aA ab AB in which the upper-case letters represent the sections carrying the text of the refrain, and lower-case letters represent new text each time they occur. The first section of music (A and a) is thus heard five times, compared to the three times that the second section of music (B and b) is heard. In terms of the poetic form, the two musical sections can each carry one or more lines of text, and it is not necessary for them each to carry the same number of lines (even though they split the refrain text between them). The simplest rondeau poem has one line per musical section giving a total of eight lines: two refrain lines (one sung three times and one sung twice) and three other lines (a single line that goes with the first refrain line and a couplet). An eleven-line rondeau would have one line of poetry in the first musical section and two in the second; a thirteen-line rondeau would have two lines of poetry in the A section and one in the B section. A sixteen-line rondeau would have two lines in each musical section and so on.

A poet would have to consider that the part of the refrain in the first musical section would have to stand alone in between the two new text segments that surround it in the middle of the piece; a composer would have to ensure that the first musical section makes as much sense going on to the second as it would going straight back to repeat the first section again with new words. In addition, the poet can make links between the musical sections in forms that have eleven, thirteen, sixteen or more lines by interlacing rhymes so that the same rhyme types occur in both sections.

The balade–virelai matrix

The forms that have least to do with the preceding century and that go on to dominate polyphonic song until the end of the fifteenth century belong to what Christopher Page has termed ‘the balade–virelai matrix’. 27 The similarity between these two song forms is evident also in their nomenclature. The word ‘balade’ refers to dancing, while the word ‘virelai’ suggests the turning (in a circle) that accompanied such dances. Machaut tends to call the virelai the ‘chanson baladée’ (danced song), and the equivalent form with Italian text is the ‘ballata’. Texts of these two forms are mixed together in the section of lyrics in GB-Ob Douce 308, which dates from the first half of the fourteenth century. 28 In both balade and virelai types there are a pair of verses which take the same music – perhaps with its endings tonally differentiated to give first an open and then a more closed feel; then there is new text set to music different from that used for the verses, and finally there is a refrain. In the virelai, the refrain (It. ‘ripresa’) is also performed at the very opening as well, and the music of the latter part of the new text – the ‘tierce’ or ‘volta’ – is the same as that of the refrain. In the balade the form opens with the pair of verses sung to the same music (with open and closed endings); the new section of text and music – the ‘oultrepasse’, or B section – is different from that of the refrain. Subsequent stanzas in both forms repeat the musical form from the first of the verses.

In the first half of the fourteenth century the differentiation between these two forms was widened by their musicalization. Most virelais in Machaut's output are monophonic and syllabic and thus could still be danced to, while being sung by the dancers themselves. An illustration in a mid-century copy of his Remede de Fortune , which exemplifies all the formes fixes within its narrative, shows exactly this, and this is the only song type to accompany group social activity in the story. 29 Machaut's balades are, with one late exception, all polyphonic and increasingly move towards a standard three-part texture with long melismatic passages. These are now stylized dance songs, akin to the suites of Bach in being removed from actual dancing, yet having assimilated dance forms, rhythms and gestures. Later, the virelai too moved away from syllabic monophony and was regularly sung in three parts; its popular-style dance elements were sometimes transmuted into the singing of non-musical sounds: birdsong, drums, trumpets etc., found more usually in hocket sections of the Italian caccia . 30

The lai

The word ‘lai’ has a number of etymological resonances, most of which link it to song. The Irish word loîd (or laîd ), meaning ‘blackbird's song’ has been linked to a supposed Irish origin for the form, but whether this can be linked with the musical lai that appeared in France around 1200 is not certain. The lai can be narrative or lyric, and not everything that calls itself a lai fits the non-strophic developmental form that usually characterizes it. Conversely, lai-like features can be found in songs that are variously called descort, leich, nota/notula, estampie, ductia, garip, sequence, prose, conductus, or versus. 31

Throughout the fourteenth century poetry remains an ‘art de bouche’ (oral practice); the human voice emits sounds on a seamless continuum from speech to singing. It is likely that narrative lays, like the chansons de geste , were intoned to a simple melodic formula. Like the refrain forms, the lai saw a trend towards greater regularity in the fourteenth century. Lais became longer; in the work of Machaut there is a standard pattern of 12 stanzas with the first and last having the same rhymes and the same melody, usually transposed a fifth higher for the final stanza. 32 Each stanza has a so-called double versicle set-up, so that it divides into two equally structured halves that can be sung to the same music used twice through. In this it resembles the sequence, which seems to have had an influence on the later fourteenth-century lai, rather than affecting its initial development – the thirteenth-century lyric lai is fairly freely structured, often heterometric (having lines of different lengths), and irregular in its rhyme schemes. 33 Because they are not strophic, the lai and sequence are primarily musical in their formal concept, as opposed to the metrical formal concept that dominates the strophic formes fixes . 34 Despite not being usually polyphonic (although Machaut wrote some that could be performed canonically in three parts), the lai is arguably a greater musical and poetic challenge to the composer than the other forms. 35

The madrigal

Despite the greater modern familiarity with the madrigal of the sixteenth century, the first use of this term to denote a musico-poetic genre is by Francesco da Barberino around 1313. In 1334 Antonio da Tempo lists two types – with and without a ritornello. Although da Tempo mentions monodic madrigals, The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians estimates that 90 per cent of the 190 surviving examples are for two voices (the rest are for three). 36 The earliest surviving examples, from northern Italy and dating probably from the 1320s, appear in I-Rvat Rossi 215. Despite both voices being texted in this source, the uppermost voice predominates, often melismatically, while the lower voice moves slower, emphasizing consonances. By the 1340s the madrigal had reached its final fourteenth-century form, comprising two or three three-line stanzas (with the same rhyme pattern but usually different rhyme types) set to the same music, followed by a one- or two-line terminating ritornello, often in a different mensuration. The individual heptasyllabic or hendecasyllabic lines are separated cadentially in the style found in the works of Magister Piero, Giovanni da Cascia and Jacopo da Bologna (fl. 1340–60). Jacopo also offers the first three-voice settings. The madrigal genre continued to be popular, especially in Florence, until around 1415, although from the 1360s onwards it was rivalled by the newly polyphonic ballata (see above). The final phase of the trecento madrigal saw a move away from the pastoral and courtly poetry that characterizes its early-century incarnation and towards its use as a vehicle for authorial presence in autobiographical pieces such as Landini's Musica son , as well as moralizing poetry and occasional or symbolic poems.

Liturgical music

The repertory of polyphonic French settings of texts from the ordinary of the mass was very widely transmitted, with pieces existing in multiple copies and a variety of different versions. The French mass style was highly influential, for example, on mass settings by Italian composers, although England was unique (as far as can be told by source survival) in setting mass propers polyphonically. Of the repertory's known composers, at least five can be associated with the papal court at Avignon. This perhaps explains the wide dissemination of the repertory, since Avignon was a magnet for the most internationally mobile and influential people of the period. In general, liturgical music is in three parts, although the number of voices texted varies from piece to piece and, sometimes, from source to source. 37

Music for the mass had previously been copied in generic groups, keeping items of the same kind together (Kyries, Glorias etc.). The earliest cyclic groupings – where a set of the different items of the ordinary that would be performed sequentially are placed together in the manuscript – occur in the fourteenth century. The earliest example is the so-called Tournai Mass, which sets the six ordinary texts of the mass: Kyrie, Gloria, Credo, Sanctus, Agnus and Ite Missa Est. The polyphonic setting of the last of these seems only to have been common in the fourteenth century; here it is presented as a three-voice motet also known independently from other fourteenth-century sources. 38 This harks back to the earlier liturgical function of motets as a form of troping, a trait associated with the beginnings of motet composition. 39 One Credo setting appears as part of two different cycles in manuscripts from Toulouse and Barcelona. In the Toulouse Mass the Credo seems related to the Ite, and the Kyrie and Sanctus also seem to form a pair (there is no Gloria). But in the Barcelona Mass the Credo does not seem similar to any of the highly contrasted items: only the Kyrie and Agnus might possibly be related. 40 These cycles were scribal compilations rather than compositionally intended cycles. This does not, however, invalidate their cyclicity – the manuscript layout suggests that they were used as a cycle and would have been heard as a cycle even if they were not composed as one. The expectation of unifying compositional cyclism is one that stems from hindsight and in particular reflects the nineteenth-century musicologists’ desire to find a medieval parallel for the unified symphony, whose movements were not only all the product of the same composer, but were also thematically, motivically, and/or tonally linked. 41 In this spirit much has been made of the first complete single-author cycle of the mass ordinary by Guillaume de Machaut, composed in the early 1360s for use in Marian devotions at a side altar in his home cathedral of Reims . 42 Although this seems a further way in which Machaut stands out as a central figure in fourteenth-century music history, it should be remembered that the ‘rise of the cyclic Mass’ was not a foregone conclusion at this point in music history.

Understanding the music of the fourteenth century

Studying the music of the fourteenth century still poses a number of key questions concerning historical method. How fourteenth-century music is studied is affected by how music is defined (its definition was somewhat broader then than now), how the sources are interpreted, what other materials are thought to bear on their interpretation, and how they are deemed to be relevant. There are inevitable limits in terms of what the predominantly written, predominantly clerical sources for this period can and cannot tell us. Depending on one's scholarly perspective this limitation is either a great frustration – how can we really know anything? – or a fantastic opportunity to make creative interpretative readings that best fit with the available (partial) evidence. We tend to ask questions of this music and the period that its historical actors – the people who made and heard its music, or taught and learned musica – did not need to ask. Their writings are unlikely to answer such questions directly. Among these modern concerns three stand out: the issue of the basic social context for music from this period, the issues surrounding its performance, and the issue of how to construct a chronology – a diachronic history – of music and musical culture across this period.

Social context

For sacred music, the liturgy gives at least some indication of the context in which it would have been performed. The mass is a particular kind of social and religious ritual event, well understood even if we do not know for any given piece the specifics for which particular service(s) in which particular year(s) it was used. Sometimes the texts of other pieces, especially motets, make political points that help connect them with particular occasions. However, this connection usually gives only a date that they must be later than (a terminus post quem ), rather than actually offering a performance situation; Margaret Bent has cautioned against ‘over-literal dating according to…topical references’ of the political motets in the F-Pn fr. 146 version of the Roman de Fauvel – musical pieces are not newspaper reports. 43 Even when a specific event is being commemorated – the wedding of Jean of Berry and Jeanne of Boulogne in balades by Trebor and Egidius, 44 or the installation of a specific bishop for Machaut's motet Bone pastor / Bone pastor / Bone pastor (M18) – a later adaptation or repetition of specially written music is not inconceivable. 45

For most of the song repertory, the problem of performance context is particularly acute. Who wrote, performed and listened to late medieval songs? The manuscript evidence is difficult to interpret: we often do not know precisely when or where manuscripts were compiled, how long before this the songs were written, how widely they circulated, who would have had the competence to perform them, when they would be performed, how often, who would listen, or what the listeners would make of them. Evidence for all these questions has to be sought from within the songs, whose texts are often highly stylized courtly love songs that seem opaquely general. A little more information is available for the works of Machaut since his narrative poems offer a first-person narrative persona (Guillaume) who is the alter ego of the poet-composer. Suitable caution must be exercised, however, because even when the songs purport to tell of the doings of real historical figures these are not historical accounts but literary works; nevertheless, they can point us to certain contexts. Machaut's Remede de Fortune , a long narrative poem with seven inserted musical items – one in each of the formes fixes – gives some information about the ideal(ized) use of this kind of musical poetry at court. The action is initiated when the Lady discovers an unascribed written copy of Guillaume's lai and asks him to sing it to her. The poem laments the fact that its je loves a lady but cannot tell her. When Guillaume has sung it to her, she asks if he knows who it is by; he flees in terror from revealing that it is his own song. Rehabilitated through more music and singing in a garden by the allegorical figure of Lady Hope (Esperance ), Guillaume returns to court fortified to withstand the vagaries of unstable Fortune in love by remaining hopeful of gaining the lady's love. He provides social music for a court dance (the virelai Dame en vous [V33], see above) and is able to reveal his love to the lady, although there is no happy outcome. In effect, love of Hope (which is within the lover and thus at his control) replaces love of the Lady (who is out of his control and might cause him sorrow). This gives a clear path to happiness based on an abstract spiritual quality, maintained within the loving subject. There is a clear parallel between this kind of courtly love, sublimated as endless hope, and the kind of hope that animates the Christian believer in the Middle Ages. Hope of an eventual reward that might not be in this life can keep one happy only if one loves the act of hoping rather than the presence of the reward.

Machaut's ostensibly secular courtly love motet texts can also be read through the lens of this allegory by means of their sacred plainchant tenor segments. It has even been argued that the ordered cycle of motets in the manuscripts represents a step-by-step journey from unhappiness and sin to union with the divine Beloved (Christ). 46 This is parallel to the Remede 's step-by-step journey, except that as in all the Machaut dits there is no final union with the earthly beloved lady, perhaps underscoring the point that although the feelings are meant to be of a similar strength in the two journeys, the outcome of only the spiritual journey is secure. Trusting in earthly happiness and earthly (i.e. sexual) love will not give the same guaranteed result of having that love returned as spiritual devotion will give to the surety of God's love. 47 Medieval courtiers took religion seriously, and women among them in particular needed consolation for the frustrations and perhaps boredom of court life by means of a form of entertainment that would not jeopardize social values. Making love poetry into a sublimation of natural sexual urges – shifting loving subjects into inaction, mental self-absorption and analogical understanding of their feelings as misplaced or displaced yearning for union with the divine – was an efficient and convenient way of managing the inevitable human and sexual tensions that would have arisen at court. 48

When poetry was combined in performance with the sweet sounds of polyphonic singing, its effectiveness increased even further according to the new status of music as an Aristotelian ‘leisured pursuit’. 49 Some of the precepts which apply to the music's suitability as a form of virtuous princely relaxation are already present in the work of Augustine and Isidore, but after the translation of Aristotle's ethical works in the later thirteenth century, music-theoretical arguments fairly soon incorporated more strongly worded justifications of music's virtuous power. 50 While Plato and Aristotle exhibit remarkably similar views on the proper ends of music and its role in education and politics, their main difference concerns their emphasis on music's pleasurable qualities. 51 The consoling effect of poetry is heightened and increased through the newly legitimate pleasure of music. In the long text of Gace de la Buigne's mid-fourteenth-century poem Le roman des Deduis , the character speaking in favour of falconry cites two Ars Nova pieces – Vitry's motet Douce playsance / Garison / Neuma and the chace Se je chant by Denis le Grant – ostensibly to prove that a good falconer never flies his birds in high wind or excessive heat. However, Gace's poem is a magnificent hybrid mirror-of-princes advice book, part a battle of the Vices and Virtues drawing on Prudentius’ Psychomachia , part jugement debate poem, both parts linked by the noble theme of hunting. When read as a whole, Gace's poem proposes musical poetry as a consoling antidote to the ills that it might narrate – the heat of excessive amorous desire in Douce / Garison / Neuma , or the indulgent time-wasting of a day's hunting in Se je chant . 52

Performance issues

Just as we know relatively little about specifically where and when these songs were performed, we know only small amounts about how these songs were performed. For liturgical music the defined context gives slightly clearer evidence suggesting all-vocal performance, perhaps accompanied or alternatim with an organ; with songs, lack of information about performance context connotes lack of information about performance practice. 53 Much of the musicological discussion of medieval performance practice has focused on the issue of performing forces, asking whether the top voice of a song was accompanied by instruments or by other voices. 54 This question is perhaps unduly distracting, since more important issues concern aspects of a piece to which we might in fact be able to get closer: the pronunciation of the text, the correct understanding of its relative pitches and rhythms, and a basic stylistic competence that enables us to make it clear where the music drives forward and where it hangs back, where it fulfils expectations and where it frustrates or surprises them. This would then go some way to offering a route to make a modern performance that was closer in its effects or representation (which can be analysed) rather than necessarily closer in sound (which is unknowable). 55 Our understanding of the rhythmic notation of the fourteenth century is rather good, deriving from fairly clear contemporary theoretical writings. 56 The understanding of relative pitch – there is no single absolute pitch standard for music at this period, so the notational level only guides the general placement of the overall ensemble within that particular group's performable pitches – has been more fraught, especially over the issue of accidental inflections and musica ficta . 57 The disagreements of scholars centre on whether sharpening the pitch of one voice in certain situations is at the discretion of the performer or was determined by the composer; whether the sonic product implied by the notation was always the same or whether there was scope for variation between different performances of the same piece; whether the practice is confined to cadences in the modern sense (in which they close a phrase) or in the medieval sense (of cadentia , a term which just describes a particular succession of sonorities which can and do occur at the beginning, in the middle and at the ends of phrases). From my own perspective, the cadential progression – for which I prefer to use Sarah Fuller's term ‘the directed progression’ because I do not see it reserved exclusively for closural syntax – is a defining feature of fourteenth-century musical style. 58 Neither before nor after does it seem to be so pervasive in the musical texture. The marker of the ‘modern’ style of Guillaume Du Fay in the early fifteenth century seems to be its more sparing use, and a greater reliance on extended phrases of ‘imperfect’ sonorities (sixths and thirds) in support of a less angular, even smooth, melodic line.

Chronology

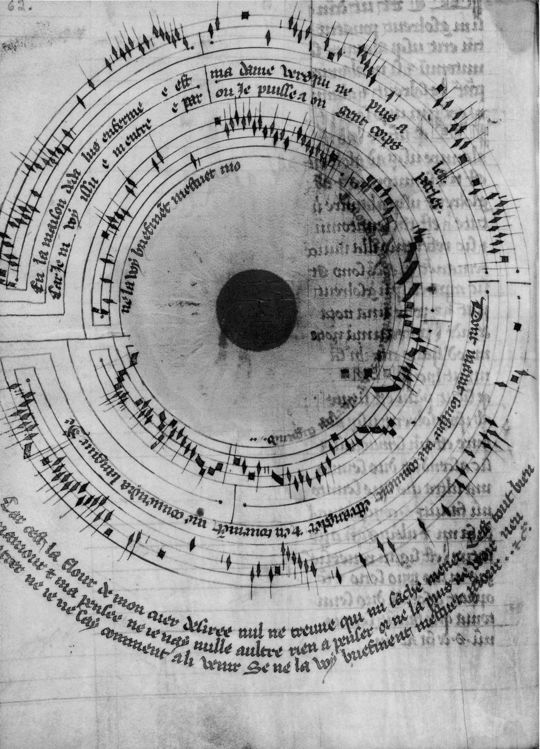

Arriving at any clear chronology for the works that have survived from the fourteenth century is more than moderately difficult. Scholars have tended to talk about an ‘Ars Nova’ (new art) succeeding the ‘Ars Antiqua’ (old art) some time around 1320, being brought to maturity in the works of Philippe de Vitry and Guillaume de Machaut before being succeeded by a mannerist ‘Ars Subtilior’ (more subtle art) after the latter's death in 1377. 59 This in turn supposedly gives way to the modern style of Du Fay and his contemporaries in the early fifteenth century. These divisions wrest circular reasoning from stylistic features in combination with evidence from notational change. Ars Antiqua notation is that which is pre-minim and pre-duple time divisions. The Ars Nova incorporates the invention of the minim (whose value was previously expressed by a series of semibreves of which the minim really is the semibrevis minima , but the value now has its own graphic indication in the form of an upstem added to the notehead). The Ars Subtilior sees not only the division of this minim value but also the deployment of ‘avant-garde’ canonic techniques, proportional note values (4 against 3 and more), texts that refer to their own musical performance, plus picture music such as the circular maze within which is copied the famous anonymous balade En la maison Dedalus . 60 The situation in Italy is treated as if parallel, with a pure period of Italian trecento notation being followed by a hybrid Italian–French phrase before the mutual accommodation of Italian elements within the ultimately triumphant French notation in the Ars Subtilior.

These tripartite schemes probably owe much to other similar ones in music historiography, notably the three compositional periods of Beethoven. 61 Philippe de Vitry's treatise Ars nova is, according to Sarah Fuller, nothing more than a retrospective writing up of what was most likely student lecture notes; certainly Vitry's involvement is indirect in this regard. 62 The Ars Subtilior – a term coined in the twentieth century – according to Elizabeth Randell Upton is the result of undue emphasis on the relatively small number of pieces that make a deliberate essay into notational complexity; 63 the term arguably says more about twentieth-century modernism and the lure of the avant-garde than it does about the music to which it refers. Nevertheless ‘subtlety’ is a term frequently used for music from 1300 onwards as a guarded kind of praise – the refined thread of a fabric, but perhaps for its detractors signalling unnecessarily recondite and self-aggrandizing compositional practice. However, it seems likely that this usage derives from a topos of ambivalence towards the subtlety of the moderns conventional from at least the twelfth century. 64

En la maison Dedalus ( Figure 5.1 ) is copied in a single manuscript now housed in the Jean Gray Hargrove Music Library, University of California, Berkeley. 65 The other contents of this source are a music theory treatise completed in 1377, which covers modes, discant and mensuration, speculative theory, and tuning of semitones (including advanced musica ficta ). The balade makes visual use of a circular maze that symbolizes the ‘house of Dedalus’, that is, the maze that Dedalus designed and built for the Minotaur. The poem compares this to the path to the lady, who is at the heart of a maze with no entry or exit. The musical staves form the tracks of an 11-course labyrinth, which has been drawn with a pair of compasses. The top voice negotiates its way through the maze by singing the song; the two lower parts are notated as one part, sung in canon – the contratenor chasing after the tenor through the maze. The pair of compasses is to the architect of the maze what the composition of the canon is to the composer – a ‘symbol of complex artistry, super-human craftsmanship’. The path of the maze is difficult to follow yet ‘it cleverly leads both to the centre and to a successful performance of the music’. 66 Aside from the use of the circular format, the other aspects of this song's complexity can be found already in the music of Machaut. His rondeau Ma fin (R14) also has a canon, drawn attention to by the visual aspect of the notation (upside down text), and its text voices the commands of the song telling the singer how to sing it (something that En la maison does not do, but which is common in several other so-called Ars Subtilior songs). 67 Machaut also projects the same kind of strong authorial persona, which claims his craft as his own and as a feat of art. In fact En la maison cites from other balades by Machaut: its line 1.5 is line 2.3 of his Nes qu'on porroit (B33), its line 1.2 is similar to B33's 2.1, and the refrain is very similar to that of Machaut's poem without music Trop de peinne (Lo164). The composer clearly knew Machaut's piece and perhaps elevates his own creativity by remaking something of Machaut, the great Dedalus of book, song and music.

Figure 5.1 Anon., En la maison Dedalus , from the Berkeley theory manuscript (US-BEm 744, fol. 31v)

One of the biggest problems in the standard periodization of the fourteenth century is that it depends on a teleological narrative not only of notation but also of style. Moreover, the relation between style and chronology is circular. All written musical collections are by definition retrospective and often transmit several decades of musical repertory. For the combination of their pristine sources and sheer numbers, Machaut's works provide a particular point of reference, although the assumption that the ordering of the manuscript represents chronology seems questionable given Machaut's interest in order for other, more aesthetic and semiotic purposes. 68 The style of other secular pieces has generally been assessed by comparison to Machaut's work, with songs of similar style dated to his lifetime. However, the criteria for stylistic features tend to be interdependent on the notational features mentioned above, which does not allow for the notational updating of pieces (a feature that certainly occurred in the Italian tradition), nor for the deliberate use of older styles. It imposes a notational teleology that certainly is hard to sustain outside the central French tradition. 69

The role of the poetry in dating is not particularly straightforward either. Viewed as a whole, the tendency during the fourteenth century is towards standardization, especially in the production of isometric balade stanzas. 70 But as a trend, this feature is not precise enough to allow dating of individual instances; there is also evidence that some poems considerably predate their settings. 71

Arguably the greatest chronological challenge that the fourteenth century suffers is to be regarded as the last of the Middle Ages, rather than an early Renaissance. Certain scholars have questioned this historiographical pigeonholing and its detrimental effect on attitudes. Vitry has been praised for his humanism, his early reading of Dante and his friendship with Petrarch. 72 Machaut has been embraced as the first ‘writerly’ author figure for musical culture, the first vernacular poète , and the first poet-composer to have an elegy in words and polyphonic music composed for his death. 73 Christopher Page has laid out the innovations of the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries to claim that it is ‘all Renaissance’ from 1200 onwards. 74 Other musicologists have looked back to the earliest coverage of the music of this period in standard textbooks to show that it is only a historical accident that music textbooks picked a later date than comparable disciplines. 75 Certainly in terms of a concern with the human and with classical antiquity, Vitry's motet texts seem obvious candidates for an earlier musical Renaissance, but the ‘medievalist’ interest in the eschatological, the ethical, and the afterlife continued well into the fifteenth century and beyond.