18 The geography of medieval music

The space where medieval music happened: the Latin West

In the 1290s an Italian friar travelled through part of what is now Iraq and found a Latin missal on sale in Al-Mawsil, north of Baghdad. The book had undoubtedly been looted from a church in one of the last Crusader possessions, probably from the port city of Acre that fell in 1291. The missal was the token of a failed endeavour to carry the ritual music of the Latin West to the Holy Land and to install it there. By the time the first Crusaders took Jerusalem in 1099, a shared body of Frankish-Roman or Gregorian chant for the mass arose whether it was night or day, and regardless of the normal patterns of sleep and sustenance, from western Spain to Hungary and from Scandinavia to Sicily. The intention had been that conquests in Palestine and Syria should become part of this Latin-Christian territory forever, and when the Crusading enterprise collapsed another Franciscan complained that ‘there is only the abominable melody of Saracens where there should only be psalmody’ . The muezzin and minaret had silenced the cantor and the bell tower. 1

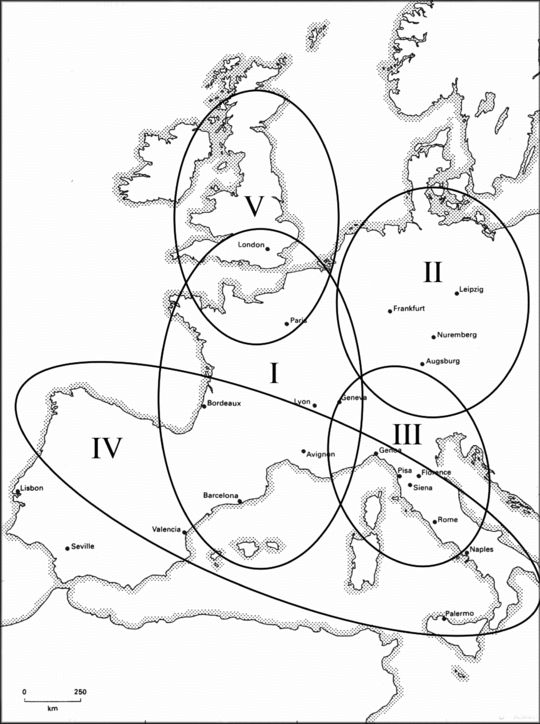

The medieval music addressed in the Cambridge Companion to Medieval Music is essentially the liturgical and vocal music, both sacred and secular, of this Latin and Western civilization. It was performed in a particular geographical space and shaped by its patterns of communication, by its shifting political configurations and even perhaps by its many and varied ecologies. Figure 18.1 shows the principal territories at issue. Bounded on three sides by water, this space corresponds to the lands where Alexander the Great had no interest in making conquests and where Greek was therefore never imposed as the language of administration and literature. Under the Roman Empire, and indeed long afterwards, Latin was the principal language associated with a functional literacy in this Occidental space and, as a result, Latin was also the only language used for Christian worship, whether for readings or for the massive repertories of sacred song, in contrast to the linguistic pluralism of the Eastern churches.

Figure 18.1 The geography of medieval music expressed as circuits of communication and long-term political history (I: West Frankish; II: East Frankish; III: Alpine Gate; IV: Romania south; V: Anglo-Norman)

To a considerable extent, this Latin Occident acquired its medieval form by accident, or rather through major territorial losses. It is easy to forget that one of the richest and most important territories in the Christian West once bordered the Sahara and vanished in 698. This was the Christian civilization of Roman, Vandal and then Byzantine Africa, strung out along the narrow lowlands from Tunisia westward to Morocco (approximately the part of Africa shown in Figure 18.1). In botanical and ecological terms, this coastal band is unmistakably of a piece with Mediterranean Europe. The significance of Africa's removal from the medieval Mediterranean system can be gauged from the riches that the littoral provided while it was still Latin and Christian. The earliest reference in any document to the psalmody of the fore-mass, destined to be of capital importance for the evolution of Western musical art, appears just after 200 in the Latin writings of Tertullian and relates to the Catholic liturgy of Carthage. The history of the chant later known as the gradual, in other words, opens in Africa. Examples between the third century and the fifth could be multiplied up to the time of Saint Augustine (bishop of a provincial African city) and beyond. A case might be made that the cradle of the Western and Latin-Christian space lies not in Rome but in Carthage, and therefore in a city whose ruins stand today in Tunisia. 2

Much of Spain was also lost to the same invaders in 711, marking the western extreme of an expansive wave that saw Islamic armies in Pakistan the following year. The conquest of Spain drove the Latin-Christian civilization of the Visigoths to the north, and when it fell this kingdom was in full flower. Ruled by Catholics from 589, Spain was highly creative in matters of liturgical music (the names of several composers are known) and could produce a scholar such as Isidore of Seville (d. 636) whose Etymologies remained a fundamental work of reference for a thousand years. The Visigothic civilization was also remarkably self-contained; its bishops in the 600s undertook far-reaching reforms of liturgy and chant with only the most passing reference to Rome. The kingdom possessed a palace administration, indeed a palatine culture, funded by the land tax and based in the royal capital of Toledo, such as kings elsewhere in the West could only envy. Had Spain not fallen, the musical achievement of the Carolingian Franks (see below) might appear in a very different light. 3

The circuits

Figure 18.1 shows the principal circuits of communication and long-term political history that shape the surviving medieval music. It cannot be stressed too strongly that this map has been drawn with reference to what survives in notation, with results that reveal a slippage between the notational record and major currents in the social, political and ecclesiastical history of the Middle Ages, to say nothing of musical life in the broader sense of all music making, regardless of whether it has left a deposit in notation or not. The immense contribution of Ireland to the monastic and spiritual history of the medieval West, for example, fails to register on this map because there are virtually no notated remains from medieval Ireland. In the same way, the rich evidence of Irish (or Icelandic) minstrelsy, mentioned in literary sources, does not register, because there is no notational record of medieval date.

These circuits are not geographical in a sense that can be explored with a physical map showing mountains, rivers and coasts. Both the Pyrenees and the Alps are crossed, and it is not the Rhine that separates I from II but a broader zone of overlap approximately corresponding to Lotharingia (> Lorraine ), a product of Frankish politics with no logic in either nature or the frontier between Romance and Germanic speech. Indeed, these circuits do not follow any linguistic boundaries save in the very approximate sense that I is largely an area of Romance speech and II of Germanic. Nor is there much in these circuits one could trace with a modern political map. They do not follow the boundaries of nation states formed in post-medieval Europe, and therefore pull away from the nineteenth-century tradition of interpreting Western European history in terms of peoples with an ethnicity expressed above all in relationships of language to territorial home, viewed as the foundation for nation states. Circuits I and II, for example, do not define a nascent France or Germany; the ‘French’ zone reaches too far south and the ‘German’ zone is inextricably linked to III as the Holy Roman Empire. To some extent, these circuits follow ecological lines more closely than any others. Most of circuit IV corresponds quite well to what botanists and climatologists define as the Mediterranean environment in Western Europe. Circuits I, II and V mostly fall in temperate Europe, and although I has a considerable southern reach its core political name, France , was still confined to lands north of Lyon as late as the seventeenth century.

I The West Frankish circuit

Between the sixth century and the ninth, when a new political order of kingship was consolidated in the West, circuits I and II defined the largest and most powerful polity in existence, namely the kingdom of the Franks. Charlemagne's conquest of Lombardy and his acclamation as [Western] Roman Emperor in 800 annexed III and created the Carolingian Empire. The foundational music of the Western musical tradition, namely Gregorian (or, better, ‘Frankish-Roman’) chant, was developed here between ca750 and ca850 in churches of the Carolingian core such as the cathedral of Rouen on the lower Seine and the abbey of St-Denis near Paris, but more consistently in the eastern reaches of I where the Carolingians were most at home, notably at the cathedral of Metz but also perhaps at heartland monasteries such as Prüm, refounded by Charlemagne's father, Pépin. It is certain that at least one Roman singer came north to teach Frankish pupils. This was at Rouen, a vital port where commodities brought by barge traffic could be unloaded onto sea-going vessels, but there are other reports of ninth-century singers travelling between the Frankish kingdom and Italy using the Alpine Gate (III). The Gregorian music spread into other circuits in ways to be described below, creating a truly Western European repertory whose melodic idioms and sense of musical line were to saturate the hearing, the artistic imagination and the musical articulacy of Western musicians for centuries to come.

Many new compositions were created here for the liturgy between the ninth and the eleventh centuries. Chant composers can be traced by name at Auxerre, Chartres, Corbie, Fleury, Montier-en-Der, St-Riquier and Sens, among other places, together with centres showing a vigorous northeastern reach such as Gembloux, Liège, Metz, Toul and Trier. The sequence appears to have emerged from circuit I in the earliest layers of this activity, but since music for the mass was otherwise a more or less closed repertory of Gregorian plainsong the aim of these composers was often to compose tropes (verbal and musical additions to an existing Gregorian composition) or to create office chants, antiphons and responsories, for new or revived cults of saints. Their most ambitious project was to create a complete matins service, both the readings and the chants, producing a complex assemblage of music, poetry and prose that was often undertaken in a conscious effort to improve on the quality of older materials. (The sense of wielding a superior Latinity, a gift of the Carolingian Renaissance, was thus a vital spur to composition.) These office chants rarely achieved a wide circulation because the saints honoured were often of little fame elsewhere, but they could make a major contribution in a local context. The city of Mons, for example, grew around the family seat of the counts and the church of St Waudru; a count translated the relics of Saint Veronus there in 1012 and soon afterwards the monk Olbert of Gembloux composed a set of matins chants, at the count's request, for the Feast of the Translation. In gratitude, the count and his wife donated lands to Olbert's abbey. Thus the monastery, the power of the comital family and the nascent settlement of Mons prospered together, and new chants helped to foster all three. 4

The rise of Gregorian chant in the northerly districts of I, and the sheer density of composers traceable there, firmly establish this as the long-term metropolitan district in the geography of medieval music. The luxuriant twelfth-century developments south of the Loire, including superbly elastic compositions in two parts set to a wide range of devotional and accentual poetry (called versus by the scribes), show Aquitaine joining the old Frankish core as a productive zone yet maintaining an independence in its choice of texts, and in the fluidity of the voices in the two-part texture, which probably owes something to Aquitaine's long geopolitical history as a far-from-compliant dependency of the Frankish (or by now French) kingdom to the north. The metropolitan status of circuit I is sometimes also very evident in developments around its periphery. In 1080, Spanish bishops at the Council of Burgos decided to replace their indigenous Mozarabic liturgy with the Frankish-Roman rite and its Gregorian chant, a decision that reflected mounting pressure from Pope Gregory VII but also from the abbey of Cluny, the massive Benedictine prayer-factory in the centre of circuit I. Several generations later, the same process of conscious assimilation to the metropolitan zone can be seen in the twelfth-century collection now known as the Codex Calixtinus, probably created in central I for use in the cathedral of St James in Galicia. This book contains the Historia Turpini , ostensibly a ninth-century account of how Charlemagne crossed the Pyrenees to Galicia and uncovered the relics of Saint James (a fine picture in the manuscript shows him riding out from Aachen to do so). There are also monophonic and polyphonic pieces in the book attributed (by a later hand) to churchmen associated with Vézelay, Bourges, Paris, Troyes and Soissons, among other places evoking Burgundy, Champagne and Picardy. Those territories had defined the principal region of monastic revival in western Europe – the Cistercians, the Cluniacs and the Premonstratensian canons had all begun somewhere there – just as they produced the greatest contribution to the Crusading enterprise. The music of the Codex Calixtinus is not a preamble to later achievements at Notre Dame of Paris. Instead, it sings circuit I, the heartland of the twelfth-century West. 5

The importance of Paris as a Capetian capital, and as a centre for polyphonic composition after approximately 1150, reveals once more the vigour of circuit I and exposes the region's deep geopolitical roots in the north. Paris is a natural fort, protected to the east by a series of escarpments, able to receive provisions along the Seine, one of the most important fluvial highways of France, and fed by the vast agricultural expanse of La Beauce. Benefactions to the abbey of St Denis, and the distribution of fiscal lands, show that Paris had been important to Frankish kings of Merovingian and Carolingian descent for many hundreds of years before Capetian ascendancy in the city added another layer. (It is salutary to remember that Paris became a centre for masters and students because there was no room for expansion on the Plateau of Laon, a Carolingian heartland city if ever there was one. This is where Charlemagne has his core estate or cambre in the Song of Roland .) By 1175 Paris was a place of exceptional opportunity with sophisticated arrangements for copying texts and music. Drawing men from all over the Latin world, it was an unparalleled and international clearing-house for musical talent. Music redacted and copied, but not necessarily composed, in Paris could reach the far ends of the Latin West, including St Andrews in Scotland (D-W 628, the ‘Notre Dame’ source W1 ) and the chapel of the royal monastery at Burgos (the Las Huelgas manuscript), centres which lie not far short of two thousand miles apart. The importance of Paris as a musical centre continued into the first half of the fourteenth century when the musical interpolations in the Français 146 manuscript of Le Roman de Fauvel (F-Pn fonds fr. 146), principally comprising monophonic songs and polyphonic motets, give Paris an unrivalled claim to be the centre of notational and stylistic developments associated today with the term Ars Nova. This was once more a function of the city's power to draw men of talent from many miles distant, including Philippe de Vitry who was probably from Champagne. 6

At this point, with Philippe de Vitry's fellow Champenois Guillaume de Machaut on the horizon, one should look back to review the geographical origins of courtly song in circuit I. Places mentioned in this survey so far, all associated with named composers, include Auxerre, Bourges, Chartres, Corbie, Fleury, Gembloux, Liège, Metz, Montier-en-Der, Paris, St-Riquier, Sens, Soissons, Toul, Trier, Troyes and Vézelay. The majority of these centres lie between the Loire and the Moselle, with a marked concentration in lands east of Paris. These are mostly regions of immense open plains produced by forest clearances (already accomplished by the beginning of the Middle Ages) or of softly undulating mountains. From the eighth century, when they were Carolingian heartland and the probable birthplace of Gregorian chant, these sweeping cornlands continuously produced their crop of musical talent. After a great many chant composers of 900–1150, the period 1150–1300 brings a new harvest with the trouvères who created some two thousand monophonic songs with texts in French (to count only the songs that survive) in an immense arc of territory reaching as far south as Berzé near Cluny in Burgundy but mostly encompassing cities, towns and smaller settlements further north such as Amiens, Arras, Béthune, Cambrai, Chartres, Coucy, Épinal, Soignies, Nesles and St-Quentin. The easterly distribution of the trouvères’ art is evident from the relatively small number of them securely connected with Paris, from the almost complete absence of Normans or Bretons among them, and from the quasi-classical status (very apparent in the manuscript record) of songs by Thibaut de Champagne and Gace Brulé, both associated with the Champenois district. In a sense, that tradition continued into the fourteenth century with Philippe de Vitry, but it survives more durably with the ‘last of the trouvères’, the Champenois Guillaume de Machaut (d. 1377), who was considerably more interested than his older colleague in vernacular song. Although Machaut was a much-travelled man with many court connections, the geographical background to his songs, both monophonic and polyphonic, lies in the great French song-making region of grands chants, ballades, rondets de carole, pastourelles and other lyric genres extending east of Paris from approximately the Plateau of Langres to Lille and Arras.

In the final decades of the fourteenth century the legacy of Machaut and other composers from the northerly reaches of circuit I was subjected to a major stylistic and geographical shift. Practised by composers such as Senleches and Solage, the rhythmic refinements of the phase in polyphonic song now commonly called Ars Subtilor were cultivated in southern regions of I at the courts of Foix and Béarn, in Aragon and Catalonia. The composers almost exclusively used texts in French, not in any form of literary language used in Romania south (IV), marking this development as an unexplained southern extrusion of a polyphonic art whose principal elements were developed further north (one of Solage's most exuberant pieces honours Jean of Berry). There is no clear connection between the Ars Subtilior and the monophonic vernacular-song traditions of circuit IV, save perhaps in the composers’ fondness for the inherently serious and grandiloquent form of the ballade, arguably their equivalent of the troubadour canso or the northern chanson. Comparable developments in circuit III, with composers such as Matteo da Perugia, also make extensive use of French texts, suggesting once more the predominant influence of the north, partly exerted through the French-dominated papal court at Avignon.

With the fifteenth century, the Seine–Moselle district of circuit I produced a crop of talented musicians all over again. The cities that will figure in the lives (and to some extent the careers) of Ciconia, Du Fay, Binchois, Josquin, Pierre de la Rue and many other Franco-Flemish musicians include Bruges, Cambrai, Ghent, Liège, Mons, St-Quentin and Tournai. This is deep Frankish territory. In the city of Tournai, today just across the Franco-Belgian frontier, Josquin walked over the concealed grave of Childeric, the father of Clovis the first Christian king of the Franks (d. 511), every time he passed the church of St Brice. In Liège, Ciconia sang barely a few kilometres from the birthplace of the first Carolingian king and the instigator of Gregorian chant, Charlemagne's father Pépin (d. 768). For the history of medieval music in its geographical aspects, these connections are the equivalent of aerial photography.

II The East Frankish circuit

Gregorian chant spread eastwards into circuit II from the core Carolingian abbeys and churches of I, and in many different ways. Some of the forces concerned were in operation well before the Treaty of Verdun in 843 that separated the West Frankish and East Frankish kingdoms with a Lotharingian band between them (note the overlap of I and II). Much was achieved by conversion at the point of a sword, especially in Saxony where Charlemagne hammered away for decades and eventually saw Paderborn emerge as a major ecclesiastical centre. The establishment of new bishoprics in the east, such as Würzburg and Salzburg, both of them eighth-century creations, created churches in which the Carolingians had a direct reforming interest, while imperial chapels founded in palaces at Aachen, Worms, Ingelheim and elsewhere established centres where the palatine chaplains, the palatini , followed the emperors to sing Gregorian chant for mass and office. The prayer confraternities, predominantly a ninth-century phenomenon, which bound abbeys and churches together throughout circuits I, II and III were of great importance in the work of dissemination, and so were ties of blood and friendship between abbots and bishops; a letter survives in which one Frankish churchman of the ninth century asks another to send a singer trained in ‘Roman’ (that is to say, Gregorian) chant as a personal favour. As in circuit I, the period 850–1100 brings many composers who created liturgical chant, including the East Frankish repertory of sequences and responsories for the offices for the Sanctorale. Again as in circuit I, these melodies were often composed against the grain of Gregorian style, so to speak, by those who regarded themselves as moderni for doing so. Composers mentioned in literary sources were active at the Bavarian abbey of St Emmeram in Regensburg (with a rich musical legacy, and surviving musical remains), Eichstätt, Fulda, Mettlach, Säckingen, St-Gall and Utrecht, to look no further. 7

Circuit II was home to a vigorous and expansionist Catholic civilization. In the 860s, missionaries directed from frontier sees such as Freising, Salzburg and Passau can be found among the Bulgars and Slavs, trying to prevail over their Byzantine competitors and characteristically insisting, with papal approval, that converts should worship exclusively in a Latin liturgy. A century later, the sheer military and political strength of the Holy Roman Emperors forced a complete reconfiguration of Hungary, shattering the tribal structure and introducing both kingship and Catholicism through German missionaries (facing down Byzantine competitors) under Prince Géza (ca970–97) on the model of realms further west. By 1000, the see of Esztergom was in existence and Hungary, gradually assimilating Gregorian chant, was established as the eastern frontier of the Latin-Christian world. By the thirteenth century, narrative sources show priests singing Latin sequences at mass in the stockade churches of Riga in modern Latvia; charters reveal hospitals, many with chapels for daily chanted masses, in Mecklenburg and Pomerania. 8

In the polyphonic arts, the contribution of circuit II was minimal, being confined before the fifteenth century almost entirely to oddities such as the polyphonic songs of the Monk of Salzburg. There was no German Machaut to marry the polyphonic techniques of the Ars Nova to an adapted form of the lyric traditions inherited from the thirteenth century. (Something similar may be said for England; the influences of I and IV, with their various traditions, were so strong that no form of vernacular polyphonic song developed in any Germanic language before the fifteenth century). Yet the situation with regard to monophonic song in the vernacular, or Minnesang, was very different. The imperial and aristocratic courts of circuit II yielded nothing in either grandeur or historical importance to their counterparts in I. In the eleventh and twelfth centuries, the Holy Roman Emperors recruited their bishops from the palace chaplains – from specialists in liturgy and chant, in other words – and the candidates for such offices were admired for a wide range of courtly skills including eloquence, decorous bearing and reserve under the stress of court life with its many intrigues. Courtliness, or curialitas , is insistently celebrated in the biographies devoted to these men when they became bishops, providing an open window onto the milieu where German courtly song was beginning to emerge by 1150 or so. The range and sophistication of the musical arts that such a milieu could encourage are well illustrated in poems such as the Latin Ruodlieb of ca1000 and the thirteenth-century Tristan of Gottfried von Strasburg. The celebrated Carmina Burana manuscript (D-Mbs clm 4660), though using unheighted neumes, also suggests the sophistication of vernacular and Latin song at the German courts and in the monastic or cathedral refectories of the Empire. The musical remains of courtly lyric in various dialects of Middle High German are much less abundant than those in French, but they are enough to reveal an art of song deeply indebted to contacts with circuit I. The earliest German songmakers, for example, who were for most part Rhineland and Westerly poets of the period 1150–1200, seem to have derived their contact with troubador lyric through French intermediaries (that is to say circuit II reached through I into IV). From there the art of German lyric expanded in the thirteenth century to fill the lands of the Holy Roman Empire, embracing all of present-day Germany (including the Low German dialect area of the north), Austria and German-speaking Switzerland. 9

III The Alpine Gate

There are two principal ways of viewing this circuit. For the period 800–900, it principally figures as the zone that gave elements of the Roman liturgy, including musical materials, to the Franks in circuit I, and which then became the district where the immense cultural achievements of I were gathered and transmitted through transalpine links to northern and central Italy. For the period 900 onwards, circuit III is much more closely linked to circuit II, for the two interlink to form the transalpine polity of the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation.

Gregorian chant came to northern Italy with Charlemagne's conquest of Lombardy in 774, as witness the magnificent Monza cantatorium, one of the earliest sources for the Gregorian gradual and probably copied in Francia during the ninth century then taken across the Alps to Monza by an emigrant Frankish bishop or abbot. By the ninth century, many churches in circuits I and II were bound in ties of prayer confraternity to houses of III, further establishing lines of transmission. Maritime contact between I and III could be fluent in the warmer months when the sea was open, but the ninth century brought a shift to the transalpine land route. This helps to explain how an abbey in an obscure place like the monastery of St Gall could mature into a wealthy house and become a major centre of Frankish-Roman chant with associated arts composition (including a major contribution to the sequence repertory) and of notation carried to a level of the utmost sophistication. The house chroniclers of St Gall cherished especially vivid (and mostly apocryphal) stories of Roman singers passing northwards through the Alpine Gate and remaining in their abbey to teach pure Roman chant. 10

There were two principal non-Gregorian liturgies in III, the Ambrosian and the Beneventan, the former reflecting the wealth and independence of what had once been a Western-imperial capital and the latter the long-standing (but precarious) autonomy of the Lombard duchy of Benevento. In the half-century 1050–1100 that produced the First Crusade and the Spanish bishops’ decision to suppress the Mozarabic liturgy in favour of the Frankish-Roman, Pope Stephen X (1057–8) demanded the end of Beneventan chant at the great abbey of Monte Cassino and the imposition of the Gregorian. Monte Cassino at this time was a major musical centre, home at various times to composers such as Leo of Ostia, Alfanus (also a physician, a reminder that Salerno and the Greek south of Italy are not far away) and Alberic (a composer and theorist). Stephen IX was a Lotharingian, appointed as part of the Holy Roman Emperors’ policy to put trusted northerners on the throne of Saint Peter instead of the scions of feuding Italian families whom the Germans were inclined to regard as deeply untrustworthy. The kind of liturgical change Stephen demanded could not be accomplished overnight, but with the decisions at Monte Cassino and Burgos, only a few decades apart, a little more of the Latin-Christian soundscape that characterizes the medieval West fell into place. 11

Soon after 1000, the ‘monk’ Guido of Arezzo, who spent all or most of his life in III, gathered up existing techniques of notation and created what is arguably the defining technology of the Western musical tradition: the staff with meaningful spaces as well as lines. So fluent was the movement of envoys, military retinues, traders and pilgrims through the Alpine Gate in the eleventh century that Guido's new technique was being taught in the distant imperial city of Liège within a generation of his death, perhaps less. The background to this seminal invention lies with the wealth of the Canossa family in the Po valley; enriched by rents from land reclamation and forest clearances, they were effectively Guido's patrons both at the abbey of Pomposa and subsequently at the cathedral of Arezzo where his invention was developed and tested. Equally important was the nearness of southern Italy with its wide contacts in the Arabo-Byzantine Mediterranean and links with Islamic science, manifest in the adoption of Hindu-Arabic numerals, recorded in Italy within Guido's century. (Guido's notation is essentially a form of graph, the earliest known in the Western tradition.) Finally, the context for Guido's invention should be sought in the quickening of monastic and clerical conscience in northern Italy after 1000, often prompted by lay congregations in the new hilltop towns of the incastellamento who demanded higher moral and pastoral standards from their priests. This breadth of reference is necessary, for Guido was far from being a simple choirmaster; he was remembered by the Canossa family several generations after his death as a ‘blessed hermit’, and he probably possessed a conspicuously ascetic temperament that was inseparable, in his judgement, from the highest standards in the performance of chant. He invented his notation to preserve Roman chant in its pure state (that is to say, to disseminate it in his preferred form) and went to Rome where John XIX approved it. 12

Italian sources of the thirteenth and indeed the fourteenth century contain numerous examples of indigenous polyphony whose techniques stand outside the ‘Notre Dame’ tradition, although literary records of polyphonic composition (such as the remarkable detailed references to song making by several Franciscans in the Chronicle of Salimbene de Adam, including settings of poems by Philippe the Chancellor of Paris) suggest that Parisian materials were by no means remote; they were probably brought through the Alpine Gate by the well-attested travels of Franciscan scholars attending the university. For vernacular song, including the trecento repertory, see the next section. 13

IV Romania south

By the twelfth century, Circuit IV can be traced as a large area of southern Romance speech used for a rich and interconnected culture of lyric in Gallego, Catalan, Old Occitan, Sicilian and ‘Italian’. The extensive song repertories that survive from this circuit, almost exclusively monophonic, include the massive Alfonsine anthology of the Cantigas de Santa Maria , the troubadour corpus and the lauda repertory from Italy. Much material, especially pertaining to lighter-courtly or satirical genres, has been preserved without musical notation, or only in fragments that have serendipitously survived, such as the Cantigas de amigo of Martin Codax.

The vernaculars of this circuit, even when cast in artificial literary forms, were probably comprehensible across the whole area. There was also a consensus that they were suitable for different things than the French or langue d'oïl used in the northern parts of circuit 1. Soon after 1200, the Catalan poet Raimon Vidal de Besalú wrote that French is best for romances (that is to say for narratives in poetry or prose), for retronsas (a refrain form, not well represented) and for pasturellas (a lighter-courtly and semi-narrative genre), whereas literary Occitan or Lemozi was most appropriate for high-style love songs and for lyrics of political or satirical comment. About a century later, Dante was so impressed by the long-established tradition of grave and authoritative French prose, represented by works such as the Vulgate Arthurian romances, that he praised French as an especially fit language for ‘compilations from the Bible and the histories of Troy and Rome, and the beautiful tales of King Arthur and many other works of history and doctrine’. Old Occitan prose was by no means so assured at this date, for it was not stiffened by the usage of clerics with a background in Paris or some other northern cathedral school. There seems to have been a consciousness throughout this circuit that a central and prized troubadour tradition existed whose language had a richness and dignity that made it especially appropriate for songs of love and ethical instruction: for amors and essenhamen . There was a widespread conviction that this Occitan was a quintessentially lyric medium, inspiring closely related forms of romance speech to comparable heights of literary eminence from Galicia to Sicily, and correspondingly less appropriate for the august purposes in prose that the langue d'oïl served so well. It was the privilege of those using southern romance in this circuit to share in that troubadour tradition, even though long study of the accepted literary language might be necessary to acquire proficiency. 14

Despite the importance of Gallego (the literary language of Galician-Portuguese, and an Atlantic tongue), IV is a Mediterranean circuit with the area of Occitan speech as its metropolitan district, essentially comprising the Auvergne, Aquitaine, the Limousin, Provence and Languedoc. The primacy of the troubadour material in this circuit seems undeniable, as witness the immense respect in which Dante held the art of the troubadours (while lamenting the lack of a court speech in Italian) at the eastern end of the circuit and the similar reverence shown by the Gallego poets in their imitations of troubadour forms and literary manner at the far west. It was also in this circuit that the art of vernacular song first acquired its own tradition of theory. Handbooks for those wishing to compose troubadour poetry began to appear in Spain, Catalonia, Italy and Occitania during the thirteenth century and continued to be written well into the fifteenth. Some are manuals of grammar or dictionaries; others, like the celebrated Leys d'Amors , produced in Toulouse during the early fourteenth century and existing in various versions, adapt the entire apparatus of Latin grammar and rhetoric to create a new art of good judgement in vernacular song based upon literacy, ethical discernment and the acute sensitivity to the sounds of the human voice that was one of the glories of the Greco-Roman education in grammar. Some of these manuals include references to the musical idioms of the songs, even to their mode of performance, and suggest that contemporaries were well aware that the musical language of their lyrics, including its rhythmic aspect, was not the same as that of Ars Nova songs practised in the north of circuit I, just as they regarded the literary languages of IV as essentially different from French. The Leys d'amors , in one of the most explicit remarks about musical idiom, inveighs against those who spoil the dansa by assimilating its music to the redondel and introducing ‘the minims and semibreves of their motets’. Since the compiler of the Leys d'amors , Guilhem Molinier, regarded the redondel as primarily a French-language form, this is probably a fling at very up-to-date monophonic songs like those in the manuscript of the Roman de Fauvel (F-Pn fonds fr. 146), whose notation (including unsigned semibreves) is probably to be read in the up-to-date manner codified in the dossier long associated with the name Ars Nova and regarded as a treatise by Philippe de Vitry. 15

Only in northern Italy did a genre of polyphonic song develop applying music with the ‘minims and semibreves’ of Ars Nova notation to poetry in a literary language of Romania south. The large and predominantly two-part repertory of trecento lyric with forms such as the madrigale, caccia and ballata is one of the mysteries of medieval music. More or less entirely contained by the fourteenth century, and barely known to traverse the Alps, this often determinedly virtuosic music shows signs of dependency upon earlier, extemporised practices of two-part florid counterpoint, revealing a sense of melody quite unlike anything shown by antecedent monophonic song in IV or the French Ars Nova. By the end of the fourteenth century it was gone, and manuscripts from what is now northern Italy (a zone where French was widely understood and spoken as a court language) begin to reveal extensive traces of transalpine contacts with music from the metropolitan zone, preserving much music by composers such as Binchois, Du Fay, Brassart and others from oblivion. The sheer long-term prestige of that metropolitan district is strikingly apparent in the way musical history during the first half of the fifteenth century runs in the opposite direction to the received narrative of an Italian renaissance feeding the north.

V The Anglo-Norman zone

England between 1066 and 1500 was a country of small account, producing only one pope (suggesting a massive failure of influence at the papal curia) and only one monastic order (the Gilbertines) which was of no interest elsewhere. In some respects, the music that survives unsurprisingly demands that Circuit V be drawn down to northern France. A small but remarkably precocious corpus of courtly songs with Anglo-Norman texts, and of Anglo-Norman motets, shows that there were trouvères and sophisticated polyphonists in the insular reaches of V, and numerous manuscripts (including the Dublin Troper, GB-Cu Add. 710) attest to the wealth of Latin songs in circulation, some of them truly ‘international’ pieces brought in by what has been called the ‘Channel culture’ of the twelfth and thirteenth centuries. Music redacted in Paris found its way as far north as St Andrews in Scotland. Nonetheless, there is a distinctively insular story to be told. Musicians in England heard the intervals of third and sixth in a fundamentally different way to their Continental counterparts (suggesting the use of Just rather than Pythagorean intonation) and treated them as consonances. English composers in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries sometimes assembled substantial sections of their pieces from chains of parallel chords with the third present, suggesting the closeness of extemporized techniques, and were even prepared to countenance pieces with the third in the final sonority. In other words, the long history of England's inward-looking concern with its own overflowing creativity in musical art had already begun by 1250. The music of the celebrated Old Hall manuscript, however, dating from the first years of the fifteenth century, nonetheless reveals substantial exposure to the late Ars Nova and indeed to the French polyphonic chanson of the Loqueville generation, presumably gained during the residence of household chaplains in Rouen, Paris and elsewhere during various stages of the Hundred Years War. This transplanting of the English musical language to France does much to explain the Continental reception of music by John Dunstaple and other English composers.

By 1400 there were three districts of polyphonic expertise in the West, defined by circuits I, III and V. The musicians of circuits III and V were not often in frequent or close communication (although signs of Italian influence appear in the Old Hall manuscript). For a central and European language of counterpoint to emerge it was necessary for musicians in I, III and V to come into sustained contact – or, in less abstract (and less accurate) language, for English, French and Italian musicians to pool their resources. The Conciliar movement of the fifteenth century provided the means for this to happen with results of far-reaching consequence for the rise of a European language of counterpoint to match the European music of Gregorian plainsong that was already some five hundred years old. 16