Medieval Florence

This chapter describes the circumstances surrounding the early coins of pre-Renaissance Florence and other Tuscan towns. After they issued multiple denominations, Tuscan towns encountered flaws in the theoretically self-regulating commodity money system, with its set melting points and minting points for coins of various denominations. Shortages and debasements of smaller denomination coins soon occurred. We discuss several episodes in Florence, including one that Carlo Cipolla called the “Quattrini affair.” By the time of that episode, the monetary authorities had struggled with limited success to repair the supply mechanism.

Turbulent debut of large coins in Tuscany

Our story begins before Florence had become leader among Tuscan cities. A single silver denomination, the Tuscan penny or denaro, descended from Charlemagne’s penny, was used by all Tuscan cities. Until about 1150, it was minted only by Lucca. Then prosperous Pisa issued copies of Lucca’s penny. That started a period of currency competition between the two cities, while other Tuscan cities chose to use either Lucca’s or Pisa’s penny. For example, Florence adopted Pisa’s currency in return for a rebate of seigniorage. During this period, Pisa and Lucca debased their pennies by half. 1 The currency competition ended in 1181 with a monetary agreement whereby Pisa and Lucca minted intrinsically identical but visually distinct coins, and shared seigniorage revenues. Pisa’s penny quickly displaced its rival in transactions throughout Tuscany.

The next decades saw no changes in the currency system of Tuscany until the late 1220s, when Siena and Pisa introduced a larger silver coin, the grosso worth 12d., with about the same silver content as the grosso of Venice. Within a few years, Florence, Arezzo, and Lucca also issued the grosso. All Tuscan grossi were regarded as equivalent at the time. In 1252, Florence introduced a gold coin, which became known as the fiorino d’oro, or (gold) florin.

The introduction of large denominations coincided with several debasements of the Tuscan pennies. In 1251, Siena’s authorities learned that their mint had been producing pennies at the same standard as those of Lucca, which were lighter than the standard that then prevailed throughout Tuscany. Siena’s authorities ratified that debasement after the fact. In 1255, the Tuscan cities agreed to a new standard and implemented it by 1257. That same year, Florence finally introduced its own penny. Siena cast a suspicious eye on its neighbors, periodically sending officials to assay their coins. Concerned by the variations among coins, Siena left the monetary union in 1266 and stopped coining pennies. When Siena resumed coining pennies in 1279, it did so on a standard of its own choosing. The following year, Florence broke away from Pisa and Lucca after discovering that they had debased their pennies, and adopted the standard of Siena. This ended the instability, and left Tuscan pennies in 1280 at 50% of their content in 1250.

This period also witnessed sharp increases in the exchange rates of pennies for the gold florin and the grosso. We have few quotations of the gold florin before 1275, but the evidence suggests that after being quoted initially at 20s., the florin appreciated to 36s. by 1276. The debasement and resumption of coinage by Siena and Florence temporarily stabilized the florin. At the same time, the grosso’s successor, issued at 20d. in 1260, began to appreciate relative to the penny. Premia of 5% occurred in 1264 and rose above 20% by 1277.

In a pattern that recurred again and again, the varying exchange rate between the grosso and the penny brought about new units of account: the lira a fiorini (by which was meant silver fiorini, or grossi) represented a particular quantity of grossi, while the lira di piccioli consisted of 240 pence. The authorities (in this case, the major guilds) tried to fix the exchange rate between grossi and the gold florin, an effort whose consequence was that the lira a fiorini became a unit of account tied to the gold florin.2

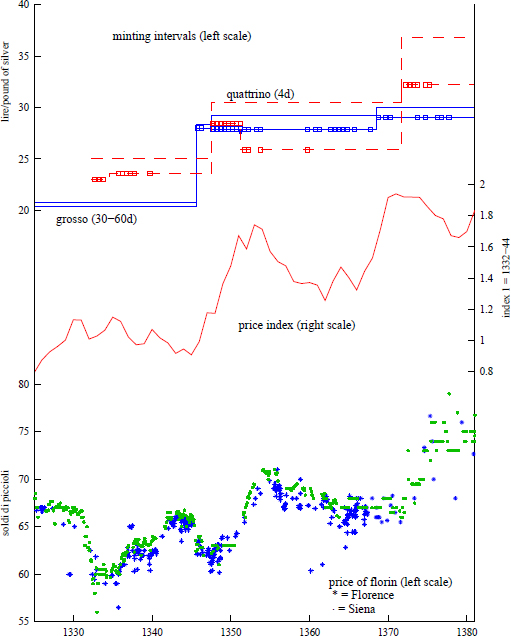

Figure 9.1 Evolution of the mint equivalents and mint prices of the small coins: picciolo (1d.) until 1332, quattrino (4d.) after, and large silver coins: grosso until 1504, barile after, Florence, 1252–1531. Against the right scale, price of the gold florin. Sources: Bernocchi 1976, Spufford 1986.

Figure 9.1 summarizes some of Florence’s subsequent monetary history. It plots the price of the gold florin in terms of the small coin, the lira di piccioli, and also shows the mint equivalent (ei/bi in our model) and mint price (e(1 − σ)/bi in our model) of a small silver coin, the quattrino, and a large one, the grosso in its various incarnations. 3 The series share an upward trend, while the gold content of the florin remained almost unchanged throughout the period. 4

The Quattrini affair

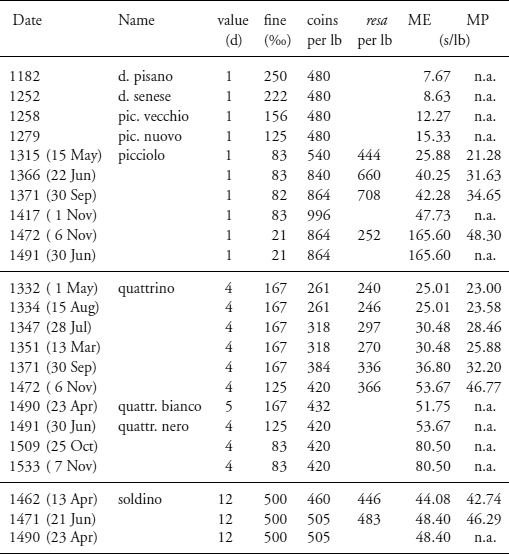

For much of the fourteenth century, figure 9.1 traces the boundaries of the melting and minting intervals for two silver coins, the quattrino and the grosso. The year-by-year observations on mint prices and mint equivalents underlying the plot are recorded in table 9.2 in appendix A of this chapter. Until 1332, the small coin in Florence was the picciolo (1d.). Thereafter it was mainly the quattrino (4d.). Though piccioli continued to circulate and were minted occasionally, in practice, the quattrino played the role of small change against the grosso (worth 60d.) and the gold florin (worth around 65s. or 780d.). A reform in 1347 had reset the intervals of the quattrino and grosso as shown in the top portion of figure 9.2. Figure 9.2 also shows, in the form of square marks, those semesters during which mint accounts indicate production of a particular coin. These marks incorporate two types of information: numerical records of quantities minted for particular years, and reports from numismatists that a particular coins was minted in a given year. The year-by-year data for both types of evidence are displayed in table 9.4 in appendix A. In our model, a coin is minted when the price level reaches the lower bound of a coin’s interval. The middle panel of figure 9.2 shows our estimate of the price level (see appendix B of this chapter), while the bottom panel shows the market quotations of the exchange rate. We shall refer to figure 9.2 to explain some things about the Quattrini affair, and a timing puzzle that we have not yet resolved.

Although the Quattrini affair occurred at the end of the period covered by figure 9.2, we note that the minting intervals for the quattrino were set above those of the grosso when the former was introduced as a new coin in 1332. Only with the reform of 1347 were the two aligned. As the model predicts, no minting of grossi was recorded before 1347, and there are contemporary reports of grossi disappearing after 1332. The motive for issuing the quattrino was “a great scarcity of silver, the fact that payments of small pennies by merchants are greatly delayed, and the fact that it is expedient to have presently a new coin of small denomination in order to supply the needs of merchants and craftsmen of the city and district of Florence” (Bernocchi 1974, 49). Ultimately, however, the scarcity and exporting of grossi prompted the reforms of 1345 and 1347 (Bernocchi 1976, 178–85).

Figure 9.2 (1) Upper and lower bounds on the picciolo, quattrino, and grosso. Minting activity is represented by a square coinciding with the minting bound of a coin for a given semester (appendix A). (2) Consumer price index constructed with a Kalman filter (see appendix B). (3) Price of gold florin in Florence and Siena (Spufford, 1986). Florence, 1325–81.

The mint records indicate that after the 1347 reform, both silver grossi and smaller coins (quattrini and piccioli) were minted in large quantities. Eventually, the flows of coinage dried up, and by 1366 foreign pennies, mainly Pisan, were invading Florence, prompting a 36% devaluation of the Florentine picciolo. Despite that, more foreign quattrini and grossi invaded Florence in 1367 and 1368, prompting further responses of the Florentine authorities. A limited debasement of the grosso in 1368, registered in a shift in the interval in figure 9.2, generated only little minting, as indicated in table 9.4. By 1370, the invasion of Pisan quattrini was large enough for the authorities to justify a substantial debasement of the quattrino. As figure 9.2 shows, that debasement put the interval for the quattrino entirely above that for the grosso.

From 1371 to 1403, the interval for the quattrino lay significantly above that for the grosso. Our model predicts that this would spell trouble. Cipolla’s account of “the Quattrini affair” confirms it.5

Our theory implies the following consequences of putting the interval for the quattrini above that for the grossi: (a) quattrini would be coined, (b) the price level would move upward into the interval for the quattrino, and (c) grossi would disappear. Quattrini were indeed minted in large quantities: in the following three years, the mint records (which survive for four out of six semesters) show that £387,000 of quattrini were minted, which is 50% more than the total minting of grossi in the whole decade 1360–69. (See table 9.4 in appendix A for the numbers.) While there was substantial minting of quattrini, as our model would predict, table 9.4 suggests that only small amounts of grossi were minted. Even that small amount puzzles us because when the interval for quattrini is entirely above that for grossi, as in this case, our model predicts zero minting of grossi, at least if the minting is done on private and not government account.

Price level movements are shown in the middle portion of figure 9.2, which plots a commodity price index for the period (see appendix B for the method of computation). The bottom panel plots observations of the price of the gold florin over the same period. Both the florin and commodities rose, although the latter seemed to peak before the debasement. Our model predicts that the price level and the exchange rate would move together. The main puzzle for us is the failure of the exchange rate to rise with the price level in the years immediately before 1370. The invasions of foreign small coins that occurred immediately before 1370, representing the ‘endogenous debasement’ described above, should have increased the price level, as indeed occurred. But our model tells us that to set off that invasion, the exchange rate (the price of grossi in terms of quattrini) should first have risen, which seems not to have occurred. Thus, though it captures many features of this episode, our model misses the detailed timing. We leave the solution of this puzzle to future research.6

The rise in prices around 1370 had important political ramifications. The Ciompi revolt of 1378 established a popular government committed to reversing the inflation. It pursued an anti-inflation policy in the form of an effort to reduce the money stock. The government bought back quattrini from October 1380 to February 1382. Within our model, that policy makes sense, though not too much could have been expected of it: a “quantity theory” policy could move the price level downward within the band determined by bi,σi, but could not drive it outside that band.

Ghost monies as legal tender and unit of account

Our model links the problem of small change to the structure of the cash-in-advance constraints: small coins can be used for large purchases but large coins cannot be used for small purchases. We take those cash-in-advance constraints as given, but view them as emerging from the exchange technologies prevailing in the market. However, the government of Florence seems to have tried to alter those exchange relations by declaring exchange rates at which coins constituted legal tender. In this section, we describe how such interventions failed to achieve their goals, but had the unintended effect of creating ghost monies, units of account not corresponding to physical objects.

Traces of those efforts to define legal tenders appear in figure 9.3, which plots prices of the gold florin from 1390 to 1535. Physically, the gold florin was virtually immutable over time.7 The ambiguity conveyed by figure 9.3 reflects the sometimes simultaneous existence of incorporeal florins, the ghosts of florins past.

In the graph, dots represent “market” prices, either direct observations of the currency market, 8 or exchange rates used in private transactions and recorded in account books. Notice the same upward trend in the market prices, a trend already displayed in figure 9.1. The graph also displays horizontal lines that illustrate a sequence of decisions by Florentine authorities to set legal tender values for gold and silver coins. Figure 9.3 shows that those actions did not prevent the rise in the price of gold coins. However, they did generate several ghost monies. Each time the authorities set a legal tender value for a gold florin, a ghost florin of the same name emerged as a silver-based unit of account, based on the legislated rate. A new name was coined to designate the real coin, and the entire process was later repeated. The names of these ghost monies (fiorino di suggello, fiorino largo, fiorino largo in oro) are on the graph.

Figure 9.3 Price of various fiorini d’oro (dots) and some official legal tender values (lines) in terms of the silver-based lira di piccioli, 1390–1535. Sources: Spufford (1986, 11–32), Goldthwaite and Mandich (1994, 97–106), Bernocchi (1976, 274–300).

That market prices usually stood above legal tender values suggests how ineffective these actions were, at least in fixing the exchange rate et. One can interpret these actions as mitigating the distributional effects of movements in et. The political consequences of the rise in the florin in 1378 seems to have preoccupied Florentine officials more than Venetian officials who, as we will see in chapter 10, were content to let the ducat drift. We are tempted to interpret the distinct actions of the Florentine officials as reflecting an emerging understanding that the rising market premium on florins was somehow linked to the structure of demand for various denominations. 9

Florentine ghost monies: details

We now consider the precise nature of these ghost monies and the restrictions that legal tender laws placed on them.10 We begin with the fiorino di suggello, or “sealed florin.” In 1294, the city created an office for the certification of gold florins. A set of florins meeting a certain standard of minimum weight was placed in a bag and the bag then sealed by a city officer. The sealed florins were exchanged without being taken out of the bag, and did not need to be weighed or assayed when priced.11 By the late fourteenth century, the use of sealed florins was common enough that they were the implicit reference for many entries in account books that simply referred to “gold florins.” The daily quotations for 1389 to 1432 published by Bernocchi (1978) are plotted in figure 9.3 with the label “fiorino di suggello.” The intrinsic content of these sealed florins is not exactly known, but was probably somewhat less than a freshly minted florin (fiorino nuovo), because the latter commanded a premium over a sealed florin.

From 1386 to 1464, in a sequence of remarkable operations, the city authorities assigned a value to this premium, increasing it over time from 5 to 20%. These legal premia are plotted in figure 9.3 with the label “fiorino nuovo” by augmenting the average market value of the sealed florin. The likely explanation is that, by the 1430s, the government had ceased to seal florins and they no longer denoted physical objects, but were instead gold-based units of account whose value the government set as a fraction of the real gold coin; or, equivalently, the government was assigning a legal tender value to the gold coin when tendered in payment of the unit of account. Since the real gold coin’s content was unchanged, the increasing premia represented an effort on the part of the government to lower the gold content of the sealed florin as unit of account. These decreases were presumably intended to offset the increase in the florin’s price in terms of silver, that is, to stabilize the value of the sealed florin in terms of silver.

In 1448, the government changed directions and began directly to fix the gold-based unit of account in terms of silver, making fixed quantities of silver coins legal tender for debts denominated in the unit of account. The result of these actions was to turn the sealed florin into a silver-based unit of account, whose price was adjusted a few times before it was abolished in 1471. Corresponding to this, a cluster of prices can be seen in the lower part of figure 9.3, trailing off at a roughly constant level in silver soldi, and disappearing in the late fifteenth century. Meanwhile, the fiorino largo or “wide florin” (a slightly wider florin minted from 1422 to match the size of the Venetian ducat) became synonymous with the real gold coin.

In 1464, the government turned to the wide florin and set its legal tender value in silver. Eventually, the “wide florin” became another silver-based unit of account (ultimately called fiorino largo di grossi or “wide florin in silver grossi”), while another expression was coined to refer to the actual gold object: fiorino largo d’oro in oro or “wide gold florin in gold” (it was also called ducato because it was interchangeable with the Venetian ducat). The result in figure 9.3 is a bifurcation of florin prices around 1480, with the gold-based unit continuing its ascent, and the silver-based unit stabilizing.

This process repeated itself yet another time, when, in 1501, the government also tried to make silver legal tender for debts in “wide florins in gold”: it, too, became a silver-based unit of account, called ducato or fiorino di monete, and individuals referred to the real gold coin as a scudo. The various legal tender provisions enacted in the fifteenth century are listed in table 9.1, mention being made of the transactions to which each provision applied.

These legal tender laws were passed in response to the rising price of the gold coin. The silver grosso was debased by 7.3% in 1402, 2.2% in 1425, 2.2% in 1448, 12.4% in 1461, by 10.2% in 1471 and by 4.3% in 1481 (see table 9.3). Comparing this with table 9.1 shows that debasements were always accompanied by a change in legal tender laws. The debasements were prompted by scarcity of silver, as the official announcements make clear. In 1448, they cite a scarcity of good grossi, displaced “for the most part” by grossi of Siena of lower fineness and weight. In 1470, a “great lack” of grossi was blamed on the fact that “grossi newly made are just as soon melted and exported” and brought back in the form of foreign coins, from Rome and Naples. Complaints of invasions of foreign black money in 1490 led to a debasement of the quattrino; in 1494, the scarcity of grossi was cited to justify making gold legal tender for silver-denominated debts (Goldthwaite and Mandich 1994, 175, 187, 191–92).

It is particularly interesting to note the attempts made to break the substitutability of silver and gold coins in payments. In 1462, when the soldino (a small coin worth four quattrini) was created, the law defined “important payments” to be those arising out of letters of exchange, government debt, dowries, or sales of real estate or jewelry, for which only gold and large silver coins could be used. The soldini were legal tender for 12d. each only in other payments. In 1464, the city went further and restricted silver grossi to small payments. The experiment quickly failed, and six months later the city made silver legal tender for all payments, large and small.

Table 9.1 Legal tender laws in Florence, fifteenth century. The table shows the rate at which certain coins (gold or silver) could be tendered for a debt denominated in a certain unit (lira, fiorino di suggello, fiorino largo), and in which type of payment. A rate of x% means that the (gold) florin could be tendered for 1+x/100 account florins. An asterisk denotes a measure that was announced as temporary.

Sources: Targioni Tozzetti 1775, 337 n237, Vettori 1738, 299–318, Bernocchi 1974, 314, 324, 342–43, 355–56; Bernocchi 1976, 296.

The Quattrini affair has supplied us with a virtual laboratory for illustrating the mechanics of our model of the medieval monetary system. Depreciations and debasements of small coins were woven together as the authorities struggled to realign coins’ minting and melting points that had been disrupted by depreciations of the small coins. By the mid-fourteenth century the authorities knew enough about their money supply mechanism to understand that debasements offered at least temporary relief for shortages. By the time of the Ciompi revolt in 1378, the authorities also understood the possible eventual inflationary consequences of those debasements. Committed to a commodity money throughout the denomination structure, policy makers used their flawed remedies for shortages of small change as best they could. We have also seen how policy makers’ efforts to manipulate exchange rates kept actual exchange rates unaltered but left a trail of ghost monies, bookkeeping entries that testified to traders’ ingenuity in undoing the effects intended by the policy makers.

Appendix A: mint equivalents and mint prices

We follow the figures in Bernocchi (1976) for coin specifications and mint prices (tables 9.2 and 9.3), with some modifications described here.

The early history of Florentine coinage is poorly documented. We do not have actual minting orders until the early fourteenth century. The fineness of the coins can be documented from money-changers’ lists of coins of the early fourteenth century (e.g., La Roncière 1973, 254; Bernocchi 1976, 128). The weight of the coins is a matter of conjecture. 12

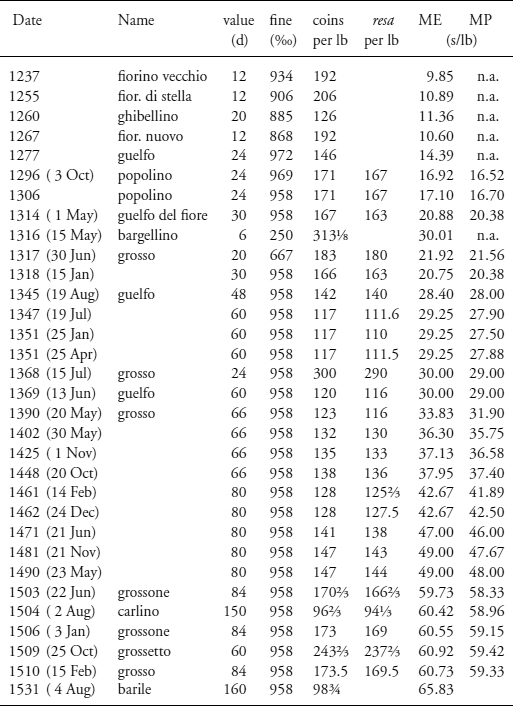

Table 9.2 Mint equivalents and mint prices of small silver coins in Florence, in soldi per pound (339.54g) of popolino silver (95.8% or 958‰ fine). The resa is the number of coins paid by the mint per pound of metal of the requisite fineness. Fineness is expressed in thousandths (‰).

There is substantial evidence that Tuscan pennies were minted at the same number of coins per pound (480) from the twelfth to the late thirteenth century, and that debasements were carried out by reducing the fineness. The fineness of Tuscan pennies (minted in Pisa, Siena, Lucca) appeared to have remained constant from 1182 to 1250, and a Sienese document of 1250 (Promis 1868, 77) gives us both weight and fineness of pennies of Siena. We simply assume that the specifications given in that document applied earlier, as Herlihy (1974, 185) has surmised. Documents in Paolozzi Strozzi et al. (1992) suggest that Tuscan cities rallied to the standard of Siena in 1257–58, and the money-changers’ coin lists cite an “old penny of Siena” at an intermediate fineness: we guess that the Florentine penny of 1258 was minted at that fineness. In 1280, Florence debased again (Gherardi 1896, 1:24, 28) and we identify the new pennies produced at that time with the “denari nuovi” in the coin lists.

Table 9.3 Mint equivalents and mint prices of large silver coins, Florence, in soldi per pound of popolino silver.

For the fiorino vecchio, the fiorino di stella, and the ghibellino, the weight is guessed to match the top of the range of surviving coins, 1.77g, 1.65g, and 2.70g, respectively (Bernocchi 1975); the fiorino nuovo is set at the same weight. The fiorino of 1277 is assumed to be of the same weight as the grosso coined in Siena that year, for which we know the specifications (Promis 1868, 78). The bargellino’s weight is set so as to make its value ⅔ of that of the grosso guelfo, to match the contemporary comment by Villani (see Bernocchi 1976, 170). The rest follows Bernocchi (1976), except for the debasement of the grosso in 1448, which is explained in Goldthwaite and Mandich (1994, 176).

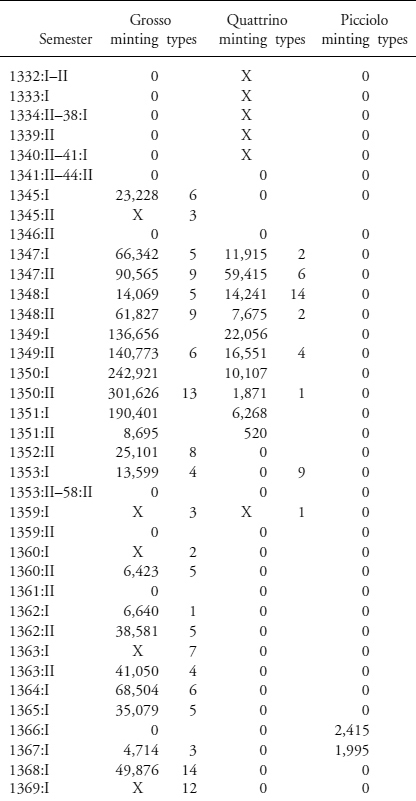

Minting

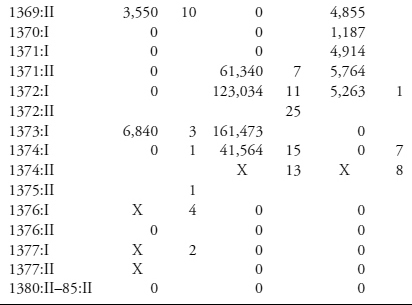

Table 9.4 summarizes existing information on minting activity. The Florentine mint operated on a semester basis (the first semester running from April to October), with different mintmasters in each semester. For some semesters, surviving mint accounts tell us how many coins of each type were minted. But minting records are incomplete in two ways: for some years we only have mention of which denominations were minted but without quantities, and for other years we have no surviving information. In the first case, we denote the unknown but positive quantity by X in the table, and presume that denominations not mentioned were not minted.

Separately, numismatists have been able to date coins by the mintmasters’ marks, and have cataloged how many different dies can be identified for each semester (Bernocchi 1975). The number of dies in a semester is an imperfect measure of minting volume. Semesters for which no information of either sort is available are omitted from the table.13

Table 9.4 Minting activity by semester, 1332–77: quantity minted (in lire) and number of known coin types. X denotes an unknown but positive quantity.

Appendix B: a price index for fourteenth-century Florence

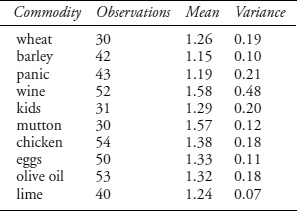

The price index used in this chapter was constructed by applying Kalman filtering techniques to a set of price data. The data come from La Roncière (1983). Table 9.5 shows the summary statistics for the series used.

Constructing a price index on the basis of these series presents a number of difficulties. The first one is due to missing data: the number of years in the interval is 57, but no series is complete, and some like wheat have substantial gaps. Yet wheat cannot be excluded from the data, since it represented from 26 to 42% of a working family’s expenditures (La Roncière 1982, 395).

Table 9.5 Statistics on available commodity price series, Florence, 1325–81. All series are on a base 1 for 1325–44. Source: La Roncière (1983, 821–37).

Another problem stems from the high variance of the series. Wine, which is one of the most complete, is also the most variable series. Wine represented 20 to 30% of an unmarried worker’s expenditures (La Roncière 1982, 394). If a consumer price index were attempted, such volatile series would be given a high weight, and their movements would dominate general price level movements. Furthermore, annual series are not available for clothing, housing, and several other important components of a household’s typical basket.

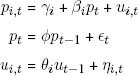

One approach is to construct an unweighted average of the available series. An alternative method consists in applying Kalman filtering, which is particularly well suited to handle missing data, and also to recovering common movements in diverse series without taking a stand on the relative weights to apply.

The model is:

where pi,t for i = 1,…, 10 are the individual price series and pt is a common factor interpreted as the general price level. The error terms ∊t and ηi,t are assumed normally and independently distributed over time, with no cross-correlations. The parameters γi, βi, φ, θi, and the variances of ∊t and ηi,t are estimated using maximum likelihood. The series pt is constructed using the Kalman smoother.

Figure 9.4 Unweighted average of prices (broken line) and Kalman-filtered price index (solid line).

The two approaches are compared in figure 9.4. The Kalman filter index is determined up to a linear transformation of the form ax+b. We choose a and b so that the average of the index for 1332–44 and 1372–81 equals that of the unweighted average. The unweighted average is shown by the broken line and displays considerably more variation. The Kalman filter index isolates more clearly the changes in trends.

1 In chapter 5, we described how this debasement led to Pillius’s question and the first discussion of the standard of debt repayment by jurists, setting off a long train of thought over the following centuries.

2 See the passage in chapter 7 on ghost monies.

3 The name grosso designates any of a number of large silver coins, worth from 12d. to 80d. depending on the time period. The guelfo is the name of one particular variety of grosso. Tables 9.2 and 9.3 list the various types of silver coins issued in Florence.

4 Strictly speaking, our model assumes that the technological rate of transformation between the metals used in large and small coins is constant, which is true when silver is used in both. In the case of the florin, the gold/silver ratio fluctuated over time. Over the long term, however, the ratio was stable, as the roughly constant gap between the series in figure 9.1 shows.

5 See Cipolla’s detailed account (1982, 63–85), from which we borrow another beautiful chapter title, and La Roncière (1983, 429–520) on this period. issued in Florence.

6 La Roncière studied prices closely and had difficulty tracing the impact of debasements on prices: “whichever coin dominates (picciolo, quattrino, grosso), the alterations it undergoes never have any significant impact on prices” (ibid., 494); “it sometimes happens that the increase in prices anticipates the weakening of the strong currency. The official alteration comes as endorsement of an earlier evolution which has taken place through the abandonment of the strong currency in favor of the clipped version of itself and, thereafter, mainly for illegally imported foreign coins” (ibid., 499).

7 The florin’s weight was higher by 0.4% from 1422 to 1433, a difference that hardly matters, since the standard deviation of the monthly market price series in Spufford (1986, 19–23) is between 0.5 and 1%. A florin 5% below the standard was very briefly minted in 1402, without causing much notice.

8 Bernocchi (1978) has published the quotations officially recorded by the city for the florin on a daily basis from 1389 to 1432.

9 As our model of “within the intervals shortages” says it is. See part V.

10 The history of these units of account is in Bernocchi (1976, 275–300) and Goldthwaite and Mandich (1994).

11 In seventeenth- and eighteenth-century Japan, gold and silver coins were wrapped in paper and sealed by the mint and by money-changers; the resulting gold and silver wraps circulated unopened.

12 Bernocchi’s method for guessing the weights relies on combining prices of the florin with gold/silver ratios to infer weights of silver coins from the known weight of the florin. Our model cautions against this method, particularly in the absence of free minting. Furthermore, the gold/silver ratios that Bernocchi uses are in effect themselves derived from prices of the florin (see Castellani 1952, 830, 873), and the method runs the risk of circularity. Indeed, in one instance where Bernocchi uses a florin price of 28s. where Castellani used a price of 29s. to derive the gold/silver ratio, the former concludes that a debasement occurred (Bernocchi 1976, 158).

13 See Cipolla (1982, 75 n22). Known quantities are listed in Bernocchi (1976, 252–58). Unknown but positive quantities are inferred from the original documents (Bernocchi 1974, 48, 56–57, 61–68, 72–77, 91–92, 129–38, 141, 159, 187–96).