INVERTED JUDAISM: THE GNOSTIC CURRENT

Some may be surprised to see Gnosticism associated with Judaism. The Gnostic texts often seem anti-Jewish, and many secondary treatments speak as if Gnosticism was plainly and simply a perversion of Christianity. Until this century, almost the only sources were the discussions in the Church Fathers. The problem was that these were hostile accounts. The patristic writers saw the Gnostics as a heresy which had broken away from Christianity, and their whole approach was to show how bad it was. Thus, they might be willing to repeat any slanders and derogatory reports without worrying too much about determining their accuracy. A similar group were the Manichaeans, a group to whom Augustine once belonged. The Manichaeans had many characteristics in common with earlier Gnostic groups and had certainly been influenced by Gnosticism.

Apart from a few texts found in the eighteenth century, it was primarily in the late nineteenth century and in the twentieth century that original Gnostic writings became available. It was also then that the one living Gnostic group, the Mandaeans, became known to scholars. It was these texts, written and used by Gnostic groups themselves, which allowed scholars finally to see their own thinking and beliefs and also to have a check on the patristic accounts. What was found included Gnostic texts which show Christian traits, Gnostic texts which show Jewish traits, and Gnostic texts which show Platonic connections. This has led many scholars to see Gnosticism as a religion in its own right but with various permutations – Christian, Jewish, ‘pagan’.

The term ‘gnostic’ comes from the Greek word gnōsis, ‘knowledge’. With a small initial letter, ‘gnostic’ is frequently used in reference to any system or tendency placing emphasis on knowledge as a way to salvation; the term is also often used loosely in discussion of various groups in New Testament writings. However, ‘Gnostic’ (often with an initial capital) is used in reference to a specific religious system with certain known characteristics. Most of the Gnostic systems known seem to have behind them a central Gnostic myth (discussed in section 5.3).

The Mandaean and Manichaean sources are discussed in sections 5.4 and 5.5 below.

These were discovered in 1945 in southern Egypt, near the village of Faw Qibli in the region of the town of Nag Hammadi. The manuscripts are in Coptic and dated to the fourth century ce; however, they represent translations of earlier Greek writings. There are the remains of 13 codices with 52 separate writings, though some writings occur more than once in the manuscripts (e.g., the Apocryphon of John occurs three times and four others occur twice). Although most of the individual writings are Gnostic, not all of them are (they include, for example, Plato’s Republic, Sentences of Sextus, Teachings of Silvanus).

The main writings of concern for our purposes are the Apocryphon of John (a ‘Christian’ writing – but the Christian elements seem confined to the framework and may well have been added to an earlier non-Christian work), Apocalypse of Adam (an apocalyptic work), and the Hypostasis of the Archons with its closely related work On the Origin of the World. Some other writings will also be mentioned below, but these four have many of the parallels with Jewish sources and Jewish interpretation to be discussed in section 5.6.

A number of patristic accounts are known, but many of these are dependent on one another and give little or no original material. Two sources which are particularly important are Irenaeus (c.130–200), who wrote a work Adversus Haereses (Against Heresies) which was widely copied and adapted by later writers, and Epiphanius (c.315–400) who wrote a treatise against the ‘eighty heresies’ called the Panarion (Cure All). Despite their obvious bias against Gnosticism, both of these writers had access to some original Gnostic writings and quote from them. The Nag Hammadi texts show the importance of both these sources for our understanding of Gnosticism.

A Gnostic myth apparently lies at the base of the various Gnostic systems known to us. It is this myth which explains what humans are, where they came from, and how they may gain the state which is their ultimate goal. No one source describes this myth in detail; indeed, it is unlikely that there was ever one single version of it. A number of sources mention it in passing or mention various aspects of it. One description of it is found in Irenaeus, Against Heresies 1.29–31. Also, a fairly detailed version is found in the Apocryphon of John and in the Hypostasis of the Archons.

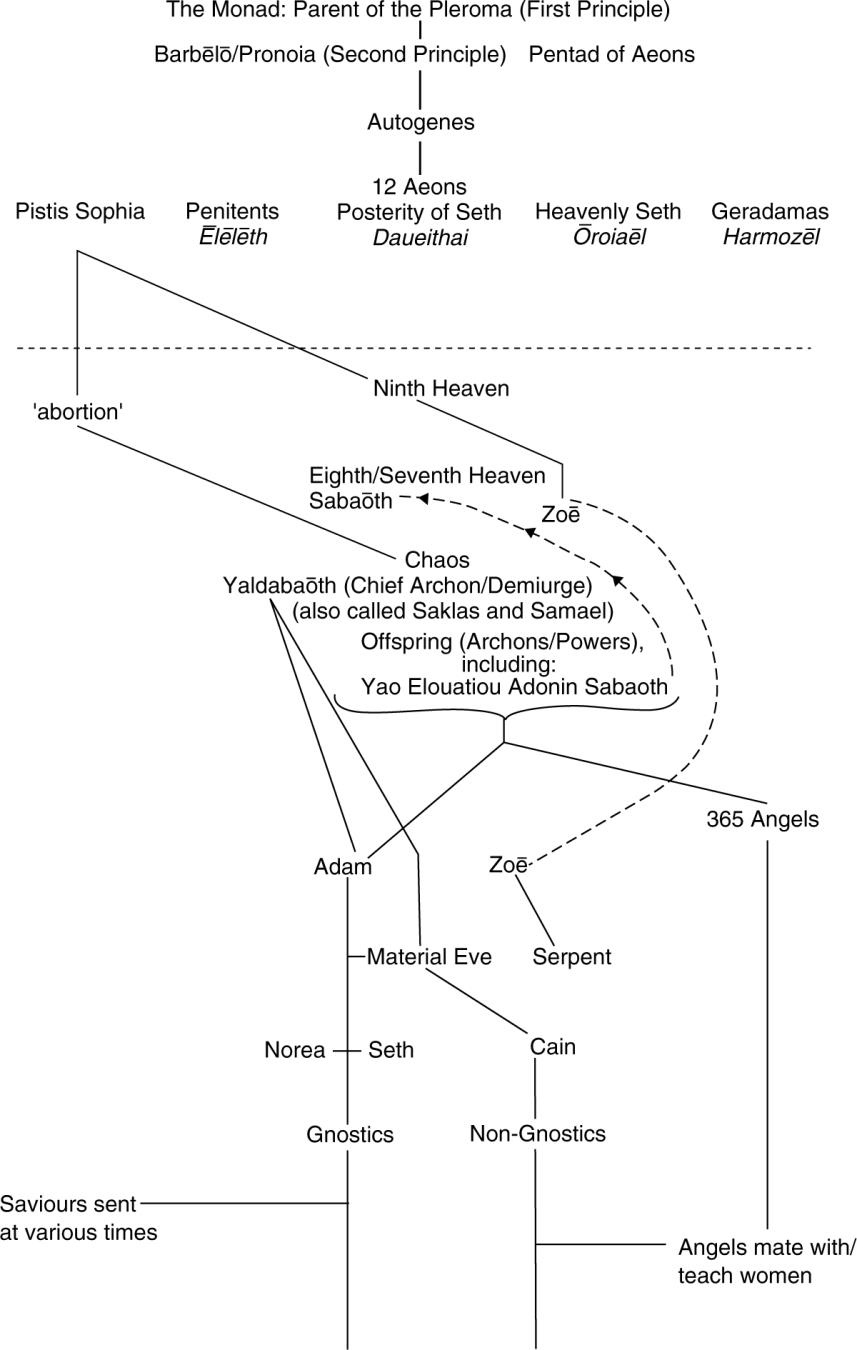

The myth as known looks very Neo-Platonic in that a single Monad or First Principle is the originator of all that is, and that the world is a series of emanations from this single unity who is God. The Monad produced a Second Principle known as Pronoia (‘foreknowledge’), also known as Barbēlō, accompanied by a Pentad of Aeons. The name Barbelo is clearly not Greek, but its exact origin is still debated. It may be Semitic or even Egyptian. The next product is the Autogenes (the ‘self-begotten’), identified with Christ in Christian Gnostic sources. The final level of the world of the Pleroma (‘the entirety’) are the 12 Aeons, one of whom is Pistis Sophia (‘faithful wisdom’).

Pistis Sophia committed a sin, however, overstepping her place in the order of things and thinking she could create without benefit of her consort or permission of the Monad. Her creation was an abortion, Chaos or Yaldabaōth the Demiurge or Chief Archon. Yaldabaoth is a Semitic name, probably from yalda (‘child’) and bô’ (‘come, go’) (cf. On the Origin of the World 100:12–14) or possibly yld (‘give birth, create’) and Sabaoth. He is clearly the creator God of the OT but, in the inverted view of the Gnostic myth, he is not good but evil. His creation is the Archons, including Yao (Yahweh), Elouaiou (Eloah or Elohim), Adonin (Adonai?), Sabaoth – all names for the God of Israel in Jewish tradition – and 365 angels.

Yaldabaoth and the Archons together create the first man Adam. They do so by using as a model the reflected image of the Pleroma, but Adam has no strength and cannot rise. Sophia then allows a spark of spirit to them to give Adam vitality; in some versions Yaldabaoth breathes life into him. In so doing, Sophia tricks the Archons, because only then do they realize that Adam is actually superior to them. At this point, they seek to imprison him and take the spirit from him.

Redemption is by means of Zoe (Greek ‘life’, equivalent to Hebrew Eve/Hāwwāh whose name also means ‘life’). She is the daughter of Pistis Sophia. It is she who comes down and invigorates Adam so that he can stand up. She also enters the Serpent and gives it wisdom (the serpent is good in the Gnostic myth), and she is the material Eve. Adam mates with this material Eve and produces Norea and Seth who give rise to the line of the Gnostics. But when Zoe leaves material Eve, the offspring is Cain, begotten by the Archons, from whose line come the non-Gnostics. The 365 angels mate with the women of the non-Gnostic line and also teach them unlawful things (parallel to Enoch, as discussed below in section 5.6).

Obviously, much of this myth is taken from Genesis, but Genesis turned on its head. What is good in Genesis is bad to the Gnostics, and what is bad is good. However, it is not just a case of having read Genesis and then making everything the opposite. On the contrary, many of the details of the myth involve Jewish interpretations of the Old Testament text – interpretations which are likely to have been well known only to other Jews. It is likely that the myth as described above had its home in some branch of Judaism.

The Gnostic Myth (An Idealized Version)

The Manichaean sect was founded by Mani (216–77 ce), after whom it was named. Much has been learned in recent years because of the discovery of original Manichaean writings. Before that scholars had to depend on writings of Christian opponents. Although some of these (such as Augustine) were knowledgeable, they nevertheless had a strong bias against the Manichaeans and cannot be trusted to represent them fairly. The recently discovered ‘Life of Mani’ gives valuable information about Mani’s early life and the origin of the group. We also have summaries of Manichaean belief from manuscripts found in many parts of the world. Mani had founded a missionary religion, and in addition to material from Persia where he did much of his work, writings have been found in central Asia, China, and Egypt.

Mani had spent part of his early life until the age of 24 in a Jewish-Christian baptismal sect. His religious system also has many Gnostic ideas and makes use of a version of the basic Gnostic myth outlined above. Whereas with other Gnostic groups we have writings but know little of how they actually lived their religion, with the Manichaeans we know how they put their beliefs into practice. They lived an ascetic lifestyle, eating no meat nor drinking alcohol. The inner circle (the Elect) eschewed sexual relations and did not even prepare their own food. They were cared for by the Auditors who were also vegetarian but were allowed to marry, though sexual relations were to be avoided as much as possible.

Mani included a number of books in his sacred canon, mainly his own original writings. However, he also incorporated a writing taken over from elsewhere: the Book of Giants. We now know from the Qumran writings that this was a Jewish book. The fragments preserved of the Manichaean book show that it was similar to the Qumran Book of Giants. Mani also evidently knew the Book of Watchers (1 Enoch 1–36).

This is a small sect which has survived in Iraq and Iran. When it was first discovered, it was sometimes referred to as ‘John Christians’ because they looked to John the Baptist as their predecessor. It is neither Jewish nor Christian, though having some features in common with both. The adherents practice a regular ritual of baptism as an important cultic rite in sacred enclosures with running water called ‘Jordans’ (yardana) and are led by priests (though in recent years only one of the sacred enclosures is left and the rites may be done beside rivers).

A considerable debate has developed as to the origin of this group. It has been argued that it goes back to Palestine in the pre-70 period, but specialists disagree about how confident one can be about this view. For example, some take the connection with John the Baptist as a reliable tradition whereas others think it was a belief adopted only secondarily at a later time. Nevertheless, many specialists accept that the group originated in Palestine before 70 but later migrated to the Mesopotamian area (though the Mandaeans’ own account of this has many legendary features). The sect itself is hostile to Judaism as such, but it has many Jewish elements and is likely to have had a Jewish origin. This view is in conformity with the thesis of an early Jewish proto-Gnosticism as discussed above.

The Mandaeans have a central religious myth which has much in common with the Gnostic myth outlined above. Their name comes from the root yd’ and means ‘knowers’, and they seem to be the one Gnostic group surviving to modern times.

5.6 Examples of Jewish and Gnostic Parallels

To the scholar of Jewish literature in Hebrew and Aramaic, a number of the names and other philological data leap out as evidence of a Jewish source. First, the name of the evil demiurge: as already noted in section 5.3, Yaldabaoth looks Semitic even though the exact origin of the name is still debated. Samael (‘blind god’) has long been known from Jewish writings as a name for the chief of the demons. Saklas is probably from the Aramaic sakla’ (‘fool’). Other names are also Semitic and known from the Old Testament, as already noted: Yao (Yahweh), Elouaiou (Eloah or perhaps Elohim), Adonin/Adonaeia (Adonai?), Sabaoth.

A very interesting passage is found in slightly different versions in two writings. This concerns the coming of the serpent to Eve in the Garden of Eden:

Then the female spiritual principle came [in] the snake, the instructor; and it taught [them] . . . (Hypostasis of the Archons 89:31–32)

. . . whose mother the Hebrews call Eve of Life, namely, the female instructor of life. Her offspring is the creature that is lord. Afterwards, the authorities called it ‘Beast’ . . . The interpretation of ‘the beast’ is ‘the instructor.’ For it was found to be the wisest of all beings. (On the Origin of the World 113:32–114:4)

What we have here is a four-fold play on words in Hebrew or Aramaic:  – which is both the proper name Eve and also means ‘life’ and ‘animal/beast’;

– which is both the proper name Eve and also means ‘life’ and ‘animal/beast’;  – serpent;

– serpent;  – instructor.

– instructor.

5.6.2 The Myth of the Fallen Angels

An old myth in Judaism is the story of the union of angels with human women. The base text is Genesis 6:1–4, but the full-blown story is found primarily in 1 Enoch 6–9 (cf. also Jubilees 5:1–7) and in the Book of Giants known from Qumran. The question of whether the myth is an interpretation of Genesis 6 or whether Genesis 6 represents a brief reflection of the myth is debated. Here are portions of the main account of the legend in 1 Enoch 6–9:

And it came to pass, when the sons of men had increased, that in those days there were born to them fair and beautiful daughters. And the angels, the sons of heaven, saw them and desired them. And they said to one another, Come, let us choose for ourselves wives from the children of men, and let us beget for ourselves children. And Semyaza [Shemihazah], who was their leader, said to them, I fear that you may not wish this deed to be done, and that I alone will pay for this great sin. And they all answered him and said, Let us all swear an oath, and bind one another with curses not to alter this, but to carry out this plan effectively . . . And they took wives for themselves, and everyone chose for himself one each. And they began to go into them and were promiscuous with them. And they taught them charms and spells, and showed to them the cutting of roots and trees. And they became pregnant and bore large giants, and their height was three thousand cubits. These devoured all the toil of men, until men were unable to sustain them . . . And Azazel [Asael] taught men to make swords, and daggers, and shields and breastplates. And he showed them the things after these, and the art of making them: bracelets, and ornaments, and the art of making up the eyes and of beautifying the eyelids, and the most precious and choice stones, and all kinds of coloured dyes. And the world was changed.

Several elements within this story are represented in the Gnostic texts: the plan or conspiracy of the angels, cohabitation of the angels with human women, the production of offspring, the motif of metals (Apocryphon of John 29.17–30.10; cf. Origin of the World 123:4–13):

And he made a plan with his powers. He sent his angels to the daughters of men, that they might take some of them for themselves and raise offspring for their enjoyment. And at first they did not succeed. When they had no success, they gathered together again and they made a plan together. They created a counterfeit spirit, who resembles the Spirit who had descended, so as to pollute the souls through it. And the angels changed themselves in their likeness into the likeness of their [the daughters of men’s] mates, filling them with the spirit of darkness, which they had mixed for them, and with evil. They brought gold and silver and a gift and copper and iron and metal and all kinds of things. And they steered the people who had followed them into great troubles, by leading them astray with many deceptions.

A play on the wording of Genesis 6:4 is also evident. The Hebrew text has hanněfilîm, which is usually taken from the root npl, ‘to fall’. The nefilim are certainly the ‘fallen ones’, both in the Enochic myth of the fallen angels and in the Gnostic text. The word also gets interpreted as ‘giants’, though how this happens is not clear. But another meaning of the word is ‘abortion’, and this finds clear expression in the Gnostic texts where the offspring of Pistis Sophia is the misshapen abortion Yaldabaoth (Hypostasis of the Archons 94:15; cf. Apocryphon of John 10:1–9).

The relationship between the Enoch and the Gnostic myths is not a simple one. The fallen angel leaders Asael and Shemihazah seem in some respects at least to be the equivalent of the Demiurge. In the various forms of the tradition, the fallen angels are cast into Tartarus or the equivalent as a part of their punishment:

For if God did not spare the angels when they sinned, but cast them into hell [Tartarus] and committed them to chains of deepest darkness to be kept until the judgment . . . (2 Peter 2:4)

And further the Lord said to Raphael, Bind Azazel [Asael] by his hands and his feet, and throw him into the darkness. And split open the desert which is in Dudael, and throw him there. And throw on him jagged and sharp stones, and cover him with darkness; and let him stay there for ever, and cover his face, that he may not see light, and that on the great day of judgement he may be hurled into the fire . . . And the Lord said to Michael, Go, inform Semyaza [Shemihazah] and the others with him who have associated with the women to corrupt themselves with them in all their uncleanness. When all their sons kill each other, and when they see the destruction of their beloved ones, bind them for seventy generations under the hills of the earth until the day of their judgement . . . (1 Enoch 10:4–13)

Similarly, Yaldabaoth is cast into Tartarus (Hypostasis of the Archons 95:10–35):

And he [Yaldabaoth] said to his offspring, ‘It is I who am the god of the entirety.’ And Zoe (Life), the daughter of Pistis Sophia, cried out and said to him, ‘You are mistaken, Sakla!’ – for which the alternate name is Yaltabaoth. She breathed into his face, and her breath became a fiery angel for her; and that angel bound Yaldabaoth and cast him down into Tartaros below the abyss.

The repentance of Sabaoth is a feature of some versions of the Gnostic myth, as already described above (Hypostasis of the Archons 95:13–96:3; cf. On the Origin of the World 103:32–107:14). It comes just after the description of Yaldabaoth’s being cast into Tartarus:

Now when his offspring Sabaoth saw the force of that angel, he repented and condemned his father and his mother matter. He loathed her, but he sang songs of praise up to Sophia and her daughter Zoe. And Sophia and Zoe caught him up and gave him charge of the seventh heaven, below the veil between above and below. And he is called ‘God of the Forces, Sabaoth,’ since he is up above the forces of chaos, for Sophia established him. Now when these [events] had come to pass, he made himself a huge four-faced chariot of cherubim, and infinitely many angels to act as ministers, and also harps and lyres. And Sophia took her daughter Zoe and had her sit upon his right to teach him about the things that exist in the eighth [heaven]; and the angel [of] wrath she placed upon his left. [Since] that day, [his right] has been called life; and the left has come to represent the unrighteousness of the realm of absolute power above.

It should be noted that in the basic Gnostic myth the God of the Old Testament is essentially split into two, the supreme first principle of the Pleroma and the wicked Demiurge. Then, in this story of the repentance of Sabaoth, a further splitting takes place. Now the God of the Old Testament (ignorant and wicked in the Gnostic view) is further split into a repentant and partially exalted being in the seventh heaven, similar to the picture in Ezekiel, and the ignorant wicked creator.

According to the mediaeval Midrash of Shemhazai, which probably has its origin in a much earlier Enoch tradition, Shemhazai (Shemihazah) repents of his deeds (quoted from Milik, Books of Enoch, p. 328):

When they [the sons of Šemḥazai] awoke from their sleep they arose in confusion, and, going to their father, they related to him the dreams. He said to them: ‘The Holy One is about to bring a flood upon the world, and to destroy it, so that there will remain but one man and his three sons.’ . . . What did Šemḥazai do? He repented and suspended himself between heaven and earth head downwards and feet upwards, because he was not allowed to open his mouth before the Holy One – Blessed be He – , and he still hangs between heaven and earth.

The Gnostic myth has a great deal taken from the Garden of Eden episode of Genesis, some points of which have already been noted; there is no need to repeat what has already been described, but this section can fill out the picture with some additional details.

One of the basic points of the Gnostic myth concerns the creation of Adam by the Archons rather than by the true God. Jewish sources of course have Adam ultimately the product of God, but Philo for one has him created by angels at God’s direction (Fuga 68–70). There is also a late tradition that Adam was only a golem (clay man) at creation until God breathed in the breath of life (Genesis Rabbah 14:8). This has an interesting parallel to the Gnostic story, but the Genesis Rabbah is probably from the fourth century ce and thus rather late.

The Nag Hammadi Apocalypse of Adam seems to be a non-Christian text (though the matter is still debated). This has clear Gnostic features, but certain sections show remarkable resemblances to the Adam and Eve tradition as found in the Jewish Life of Adam and Eve in Latin and the Greek Apocalypse of Moses. In the first part of both accounts, Adam gives a revelation to his son Seth in the form of a testament (Apocalypse of Adam 64:1–19; 85:19–31; Life of Adam and Eve 25–29; 51:3). In the Gnostic myth Adam and Eve are persecuted by the ignorant Demiurge who is actually inferior to them (Apocalypse of Adam 66:14–67:14); this has close parallels to Satan’s own story of his expulsion from heaven (Life of Adam and Eve 12–16). Both accounts tell of coming destruction both by water and by fire (Apocalypse of Adam 69:2–76:7; Life of Adam and Eve 49:2–3). Finally, in both versions Seth is instructed to write these things down on stone (tablets or on a mountain) which would survive the Flood and be available to be read by later generations (Apocalypse of Adam 85:2–17; Life of Adam and Eve 50–51). This has led some scholars to argue that a common ‘Testament of Adam’ lies behind both the Gnostic and the Jewish work.

A midrash on the serpent is found in several Gnostic accounts (Origin of the World 113:21–114:4; 118:16–120:16; Testimony of Truth 45:30–46:1). This takes the details as known from Genesis 3–4 but with a Gnostic twist. The serpent is in fact the ‘instructor’, created by Sophia to bring enlightenment to the Gnostic race. He is wise and teaches knowledge to Eve. ‘God’ (Yaldabaoth and the Archons) curses the serpent (without effect) and also Adam and Eve because they now have an advantage over the Archons. The episode illustrates the ignorance and malice of this ‘God’ because he envies the knowledge Adam gains by eating of the tree and punishes him. He is also blind because he has to question Adam about what he has done and was not able to foresee what Adam would do.

According to some of the Gnostic sources, Cain was the offspring of Eve and Samael (Hypostasis of the Archons 89:17–28; On the Origin of the World 116:13–19). A similar interpretation of Genesis, in which Cain is a product of Eve and Satan, can be found in a number of Jewish sources, though unfortunately most of these are quite late (e.g. Targum Pseudo-Jonathan on Genesis 4:1 and 5:3; Pirke de Rav Eliezer 21).

The figure of Sophia is quite important to the core Gnostic myth. Her name is the Greek word for ‘wisdom’. Within Jewish sources, there is a long history of speculation on the figure of wisdom, already beginning with Proverbs 1–9 (the dating of this section of Proverbs is still controversial). Wisdom became outwardly pictured as almost a goddess figure – as one who was separate from but alongside God. She was ultimately seen as simply a personification of God’s mind or other characteristic(s) of his, but the language used of her is to make her a divine figure in her own right. In some Jewish sources (e.g. in Philo), this figure is the Logos; in others it is Wisdom. This all creates a certain amount of tension, but the long tradition of Jewish speculation on the figure of Wisdom clearly lies behind Sophia in the Gnostic myth.

The treatise known as Zostrianos seems to take its name from the Persian prophet Zoroaster (Zarathushtra). Although very much damaged, the treatise seems to describe a heavenly ascent of Zostrianos. There are many parallels with the Jewish book of 2 Enoch in which Enoch rises through a variety of heavens (the two versions of 2 Enoch have a different number of heavens). A similar comparison can be made between 2 Enoch and the Corpus Hermeticum tractate 1 known as Poimandres. This last is a revelation about creation from Poimandres who is the Intellect of the Realm of Absolute Power. Poimandres has parallels with Gnostic writings, especially its dualism between intellect and body, between spirit and matter, and it has both the supreme intellect and a lower Demiurge. On the other hand, it does not have the hostility towards the creator found in Gnosticism generally. The writer has clearly drawn on the book of Genesis for his account of creation; indeed, it has many resemblances to Philo’s account in his Opificio Mundi.

A Jewish tradition developed around Solomon that he was an exorcist and a master of demons. This is already found as early as Josephus (Antiquities 8.2.5 §45):

And God granted him knowledge of the art used against demons for the benefit and healing of men. He also composed incantations by which illnesses are relieved, and left behind forms of exorcisms with which those possessed by demons drive them out, never to return.

This tradition is given elaborate testimony in the Testament of Solomon from the early centuries ce in which Solomon harnesses the demons for the building of the temple, as well as imprisoning some within it:

When I heard these things, I, Solomon, got up from my throne and saw the demon shuddering and trembling with fear. I said to him, ‘Who are you? What is your name?’ The demon replied, ‘I am called Ornias.’ . . . After I sealed [the demon] with my seal, I ordered him into the stone quarry to cut for the Temple stones which had been transported by way of the Arabian Sea and dumped along the seashore. (2:1–5)

Then I ordered him [the demon Kunopegos] to be cast into a broad, flat bowl, and ten receptacles of seawater to be poured over [it]. I fortified the top side all around with marble and I unfolded and spread asphalt, pitch, and hemp rope around over the mouth of the vessel. When I had sealed it with the ring, I ordered [it] to be stored away in the Temple of God. (16:6–7)

This extra-biblical tradition is also known by the author of the Testimony of Truth (69:32–70:24):

Some of them fall away [to the worship of] idols. [Others] have [demons] dwelling with them [as did] David the king. He is the one who laid the foundation of Jerusalem; and his son Solomon, whom he begat in [adultery], is the one who built Jerusalem by means of the demons, because he received [power]. When he [had finished building, he imprisoned] the demons [in the temple]. He [placed them] into seven [waterpots. They remained] a long [time in] the [waterpots], abandoned [there]. When the Romans [went] up to [Jerusalem] they discovered [the] waterpots, [and immediately] the [demons] ran out of the waterpots as those who escape from prison. And the waterpots [remained] pure [thereafter]. [And] since those days, [they dwell] with men who are [in] ignorance, and [they have remained upon] the earth.

This chapter has been the most speculative of the four currents in Judaism. Was there really a ‘gnostic’ current in Judaism? Many scholars feel that the examples noted above prove that there was a Jewish form of Gnosticism or at least proto-Gnosticism at one time. The main problem is that Gnosticism seems anti-Jewish. We must keep in mind, however, that Christianity became anti-Jewish even though it clearly originated in Judaism. To get from Judaism to Gnosticism is not easy, but it is certainly not impossible. Various aspects of Gnosticism already have their parallels in known forms of Judaism. One does not have to bridge the gap all in one go.

The clearest connections are found with the book of Genesis, but it is not just the Genesis of the Old Testament text. It is, rather, a Genesis interpreted. It is a Genesis expanded and developed by a long period of speculation, commentary, and growth of tradition. This form of the Genesis story is not likely to have been easily accessible to non Jews. The best explanation seems to be that it originated in a form of Jewish Gnosticism or proto-Gnosticism.

More difficult is the claim that this Jewish Gnosticism was a pre-Christian Gnosticism. What is non-Christian is not necessarily pre-Christian. On the other hand, we find Gnosticism already well attested in the second century ce. Also, the situation in Judaism after 70 was not conducive to this sort of development; it seems likely that any Jewish proto-Gnosticism was already in existence before the 66–70 war.

What this chapter has helped demonstrate is the complexity of Judaism before 70. In addition to Gnosticism, one could go into such matters as magic and the other esoteric arts (astrology, divination, necromancy, and the like) which were also aspects of Judaism of the time, but that would require another full study. A proper understanding of Jewish religion and culture requires that all these things be taken into account. Again, it demonstrates how wrong-headed is the image that so many people work with, which is that of the modern Orthodox or even Hasidic forms of Judaism. On the contrary, modern Judaism itself is not monolithic (secular, Conservative, and Reform Jews far outnumber the Orthodox, and the Hasidic movement is in fact very small), and modern Judaism is in any case a centuries-long development. Many of the pre-70 strands of Judaism were cut off by the 66–70 war or disappeared soon afterwards because of the changed circumstances. Others developed in their own way, leading away from Judaism itself: the Christians and perhaps the Gnostics. The mystical, magical, and other currents also continued and flourished alongside the developing rabbinic Judaism, though primarily underground.

For a translation of the main Gnostic texts, see:

Robinson, James M. (ed.), The Nag Hammadi Library in English (San Francisco: Harper, revised edition, 1989).

Layton, Bentley. The Gnostic Scriptures: A New Translation with Annotations and Introductions (London: SCM, 1987).

For a general introduction to Gnosticism, see Layton, The Gnostic Scriptures, and:

Rudolph, K. Gnosis: the Nature and History of an Ancient Religion (Edinburgh: T. & T. Clark, 1983).

Filoramo, Giovanni. A History of Gnosticism (translator A. Alcock; Oxford: Blackwell, 1992).

On the question of Judaism and Gnosticism, see Grabbe, Judaism from Cyrus to Hadrian, especially 8.2.13 (pp. 514–19), and

Pearson, B. A. ‘Jewish Sources in Gnostic Literature’, in Michael E. Stone (ed.), Jewish Writings of the Second Temple Period (Compendia rerum iudaicarum ad Novum Testamentum 2/2; Minneapolis, MN: Fortress, 1984), 443–81.

Fallon, Francis T. The Enthronement of Sabaoth: Jewish Elements in Gnostic Creation Myths (Nag Hammadi Studies 10; Leiden: Brill, 1978).

Reeves, John C. Heralds of that Good Realm. Syro-Mesopotamian Gnosis and Jewish Traditions (Nag Hammadi and Manichaean Studies 41; Leiden: Brill, 1996).

Stroumsa, Gedaliahu A. G. Another Seed: Studies in Gnostic Mythology (Nag Hammadi Studies 24; Leiden: Brill, 1984).

On the Mandaeans and Manichaeans, a selection of texts in English translation is found in:

Haardt, Robert. Gnosis: Character and Testimony (Leiden: Brill, 1971).

Foerster, Werner. Gnosis: A Selection of Gnostic Texts II. Coptic and Mandaean Sources (Oxford: Clarendon, 1974).

Part of the Life of Mani has been translated into English, as has been one of the main Manichaean texts:

Cameron, R., and A. J. Dewey. The Cologne Mani Codex (P. Colon. inv. nr. 4780): ‘Concerning the Origin of his Body’ (Society of Biblical Literature Texts and Translations 15; Early Christian Literature 3; Atlanta: Scholars, 1979).

Gardner, Iain. The Kephalaia of the Teacher. The Edited Coptic Manichaean Texts in Translation with Commentary (Nag Hammadi and Manichaean Studies 37; Leiden: Brill, 1995).

On the Manichaeans, the standard treatments are:

Lieu, Samuel N. C. Manichaeism in the Later Roman Empire and Medieval China (2nd edn; Wissenschaftliche Unter-suchungen zum Neuen Testament 63; Tübingen: Mohr, 1992).

— Manichaeism in Mesopotamia and the Roman East (Religions in the Graeco-Roman World 118; Leiden: Brill, 1994).

— Manichaeism in Central Asia and China (Nag Hammadi and Manichaean Studies 45; Leiden: Brill, 1998).

For an introduction to the Mandaeans, see Rudolph, Gnosis, ch. , and his preface to the translated texts in Foerster. See also the following, which includes a number of central texts in translation:

Lupieri, Edmondo, The Mandaeans: The Last Gnostics (transl. Charles Hindley; Italian Texts and Studies on Religion and Society; Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2002).

A translation of the main Jewish texts mentioned here can be found in Sparks (ed.), Apocryphal Old Testament, and Charlesworth (ed.), Old Testament Pseudepigrapha. The Qumran fragments of Enoch and the Book of Giants are discussed in the following book (which also gives the text and translation of the medieval Midrash of Shemihazai [pp. 322–29]):

Milik, J. T. The Books of Enoch: Aramaic Fragments of Qumran Cave 4 (Oxford: Clarendon, 1976).

The main commentary on much of 1 Enoch is the following (a second volume is in preparation):

Nickelsburg, George W. E. 1 Enoch 1: A Commentary on the Book of 1 Enoch, Chapters 1–36, 81–108 (Hermeneia; Minneapolis, MN: Fortress, 2001).

A comparison of the Qumran and Manichaean Book of Giants is given by:

Reeves, John C. Jewish Lore in Manichaean Cosmogony: Studies in the Book of Giants Traditions (Monographs of the Hebrew Union College 14; Cincinnati, OH: Hebrew Union College Press, 1992).

The main arguments against pre-Christian Gnosticism are found in:

Yamauchi, Edwin M. Pre-Christian Gnosticism: A Survey of the Proposed Evidences (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1973).