Chapter 7

Set Goals for Yourself

Never play another person’s game. Play your own.

— Andrew Salter

A professor we admired used to tell his graduate students that changing yourself is like planning a trip: you have to find out where you are now, decide where you want to go, then figure out how to get there from here.

Much of the material in this book so far has been devoted to helping you find out where you are now in relation to assertiveness. In the following chapters, we’ll be focusing on ways to “get there.” This chapter is the bridge — to help you decide where you’re headed. Identifying your needs and setting your goals may be the most important and most difficult steps of all.

“How Do I Know What I Want or Need?”

Assertiveness training evolved out of the idea that people live better lives if they can express what they want or need, if they can let others know how they would like to be treated. Some folks, however, find it hard to know what they really want from a relationship. If you have spent most of your life doing for others and believing that your needs are not important, it can be quite a chore to get a handle on just what is important to you!

Some people do seem to know exactly how they feel and what they want. If the neighbor’s dog is barking loudly, the feeling aroused in them may be annoyance or anger or fear. These folks are able to translate the feeling, get to the key issue at hand, and make the needed assertions, if any.

Others find it difficult to know what their feelings are and what they want to accomplish in an encounter. They often hesitate to be assertive, lamenting, “Assert what ? I don’t know what I want!” If you have such trouble, you may find it valuable to try to label your feelings. There are dozens of feelings we humans experience, of course. Anger, anxiety, boredom, discomfort, and fear are common ones. A few more that show up frequently are happiness, irritation, love, relaxation, and sadness.

Some of us need an active first step to get in touch with our feelings. When you don’t recognize what you’re feeling or what you need in a situation, it often helps to say something to the people involved: “I’m upset, but I’m not sure why.” Or perhaps, “I’m feeling depressed” or “Something feels wrong, but I can’t put my finger on it.” Such a statement will start you on an active search for the feeling you’re sensing and will help you begin to clarify your needs and goals.

Perhaps it is a fear of some sort that is preventing you from recognizing your feelings — a type of protective mechanism. Or you may just be so far out of touch with your feelings that you have virtually forgotten what they mean. Don’t get bogged down at this stage. Go ahead and try to express yourself. You will probably become aware of your goal even as you proceed. Indeed, maybe all you wanted was to say something! If you do begin to recognize the underlying feeling and decide to change directions midstream (“I started out angry but realized that what I really wanted was attention!”), that is a constructive step.

You can go a long way toward clarifying your feelings in a specific situation by identifying your general life goals. Assertiveness does need direction; while it seems to be a good idea in general, it is of little value for its own sake.

“Hello, Needs? It’s Me, Tim Id.”

Ignoring their needs is one of the many ways people fail to care for themselves. Pleasing others and denying themselves are common choices for such individuals. Maybe you’re one of them? Most are not consciously aware of their needs, so they find it difficult to express them in relationships.

One of the earliest serious examinations of needs was that done by psychologist Abraham Maslow. If you’ve had a course in general psychology, you’ve probably come across Dr. Maslow’s “hierarchy of needs,” usually depicted in the form of a pyramid consisting of multiple layers, with basic physiological needs as the foundation, then built up in turn through the needs for safety, belongingness and love, esteem , and self-actualization.

An excellent contemporary resource for helping us to identify our needs is the work of Dr. Marshall Rosenberg, who has noted several categories of human needs in his book Nonviolent Communication. Among them are autonomy (choosing your goals, values, and plans), integrity (meaning, self-worth), interdependence (acceptance, closeness, warmth, community), play (fun, laughter), spiritual communion (beauty, harmony, peace), and physical nurturance (air, food, shelter).

As you consider and discover your needs that are not being met in a relationship or life situation, it becomes easier to know how to handle it. If a relationship is not providing you the warmth you need, you can decide how to ask for it assertively. If your neighbor’s amplified music or barking dog is denying your needs for rest and peace, you can assertively explain that to the neighbor (rather than just complaining about the noise).

You’ll find at times that your needs may be in conflict. You may wish, for example, to keep a friendly relationship with your neighbor but also wish to quiet his noisy dog. If you confront him about the dog, you may risk the good relationship. At such a point, clarification of your own needs and goals — which ones are most important to you — will help you decide what to do and how to do it.

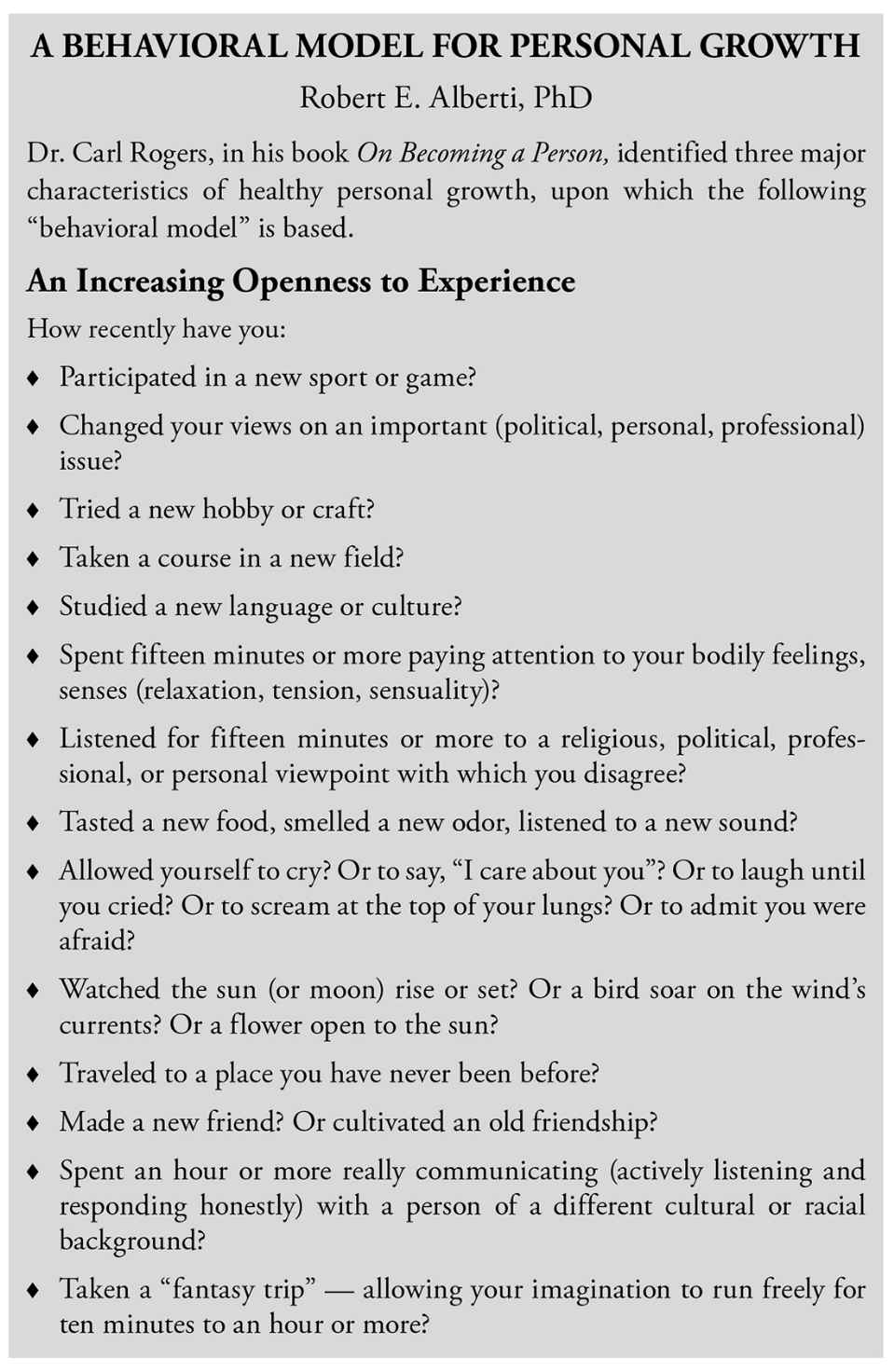

A Behavioral Model for Personal Growth

Dr. Carl Rogers is recognized as the most influential psychological thinker of the second half of the twentieth century. His ideas were the major influence in the development of what’s known as the “human potential movement.” The list on the following two pages was prepared in the early 1970s in an attempt to translate Rogers’s ideas into specific behaviors that could be carried out. We think you’ll find it helpful, as you consider goals for your own growth, to read and ponder this “Behavioral Model for Personal Growth.”

Structuring Your Goals

Okay, let’s get specific. You want to write in your journal (You are keeping a journal, right?) a few goals that will help guide your work on assertiveness in the weeks to come. Start by thinking creatively about what you want to get out of this program of personal growth. Brainstorm about your assertiveness, writing down anything that comes to mind. Write quickly. Don’t ignore or criticize any idea, no matter how silly it may seem. Be as open-minded as you can.

After you have compiled a list of possibilities, you’ll need to pare it down to a short list of specific goals. What should go on that list? Consider six key criteria as you decide: personal factors, ideals, feasibility, flexibility, time, and priorities. Make each of your own goals “qualify” in terms of those six criteria.

Personal Factors

As you evaluate your specific goals for assertive growth, use your discoveries about yourself from the Assertiveness Inventory in chapter 2 and your journal entries.

In chapter 3, “Keep Track of Your Growth,” we suggested that you keep track of your assertiveness using five categories:

- Situations that are difficult or easy for you

- Key people in your life

- Your attitudes, thoughts, and beliefs

- Your behavior, the skills you possess relating to assertiveness, such as eye contact, voice volume, and gestures (more about these in the next chapter)

- Obstacles to your assertiveness, such as certain people or fears

Spend some time now reviewing your journal, looking for ideas that will help you to define goals for yourself.

You may, for example, find a pattern of difficulty dealing with a coworker who is pushy. Maybe she insists on doing things her way, doesn’t listen to your ideas, and ignores your good suggestions. Your response may be to withdraw, avoiding confrontation by swallowing your disagreement and keeping quiet. You may also be wasting time and energy as you look for ways to stay clear of her and work on your own. Could an assertive approach help you here?

Ideals

There are probably many people you admire. If you select the qualities of one or more “models” of assertiveness as ideals toward which you can strive, you’ll have some specific behavioral goals already in mind. A well-chosen ideal will inspire you to stick to your goals.

A good model may be a best friend, a beloved teacher, a public figure, a community leader, an entertainer or actor, a family member, a clergyperson, a business executive, or someone of historical importance. This person’s behavior can be one basis for your goals.

You can go a long way toward clarifying your feelings in a specific situation by identifying your general life goals.

Focus on the qualities that you want to attain, such as self-confidence, courage, persistence, and honesty. Measure your behavior against the model you have chosen.

Think often about the person. Let your reflection on your model’s behavior give you energy to keep at your own process of improvement in assertiveness.

Feasibility

As we have suggested at various points in Your Perfect Right, go after your changes in assertive behavior slowly and in small steps to increase your chances of success. Don’t set your goals too high and risk early failure. Instead, do a little each day, advancing step by step.

Author-philosopher Morton Hunt illustrates this advice in a poignant way. He tells the story of how he learned to cope with major life stresses through a harrowing experience at age eight. Hunt and several friends climbed a cliff near his home. Halfway up, he got very scared and could go no farther. He was caught: to think of going either up or down overwhelmed him. The others left him behind as darkness approached.

Eventually, his father came to the rescue, but Morton had to do the work. His father talked him down, establishing a pattern for him to overcome future fearfulness. The advice was timeless: “take one step at a time,” “go inch by inch,” “don’t worry about what comes next,” “don’t look way ahead.”

Later in life, when faced with major fearful events, Hunt remembered those simple lessons: don’t look at the dire consequences; start with the first small step, and let that small success provide the courage to take another and another. The small-step goals will add up until the major goal is accomplished.

The suggestions Hunt’s father gave form an excellent approach to growth in assertiveness. Remind yourself to break your major goals into small, manageable steps. Take your time; the end will be in sight soon. You’ll notice changes in yourself. You’ll reach your goals, one step at a time.

Flexibility

Deciding whether and how you’d like to change can be a complex and never-ending process. Goals are never “set”; they constantly change as you and your life circumstances change.

Maybe at one time you wanted to finish school, and when you did, a whole new range of possibilities suddenly opened up. Or perhaps you sought to make $50,000 a year, and by the time you reached that level, you needed $100,000! Then there was that promotion; when you got it, you found you didn’t like your new responsibilities as well as your old.

So change itself is the constant factor. Keep your goals flexible enough that you can adapt to the inevitable changes that will come in your life.

Time

How about listing your goals according to how long it will take to accomplish them? Here are some examples of assertiveness goals:

Long-Range Goals

- Behave more assertively with my spouse

- Take more risks in my life

- Reduce my anxiety about behaving assertively

- Overcome my fear of conflict and anger

One-Year Goals

- Compliment those close to me more frequently

- Speak out in front of groups more often

- Say no and stick to it

- Improve my eye contact in conversation

- Not say “I’m sorry” or “I hate to bother you” so much

One-Month Goals

- Return the faulty vacuum cleaner to the store

- Say no to the finder of committee members at work

- Express my love for my spouse in some way every day

- Invite my new neighbor over for coffee

- Start listening to recorded seminars (online or on CDs) about speaking out

Customize these lists to your own unique needs — the possibilities are virtually limitless!

Priorities

After determining and grouping your short-range, mid-range, and long-range goals, further sort each one by priority — identifying each goal as “top drawer,” “middle drawer,” or “bottom drawer,” accordingly:

- Top-drawer goals are those that are most important.

- Middle-drawer goals are those that are important but don’t need to be accomplished right away.

- Bottom-drawer goals can be put off indefinitely without causing great stress.

Here’s a sample of what your priority chart could look like:

If you select two top-drawer goals from each of the three lists, you’ll have six top-priority items to work on (or start working on) during a period of one month. Each month you can select a new list. Some goals will stay top drawer, others won’t.

Goal for It!

As you’ve worked your way through this chapter, you’ve begun to pay closer attention to your needs and you’ve identified some possible goals for your growth. You’ve also evaluated your goals and begun to sort them according to their importance and feasibility.

Select — and write in your journal — a few goals to work on over the next weeks and months.

Throw out those that are too far-fetched or out of reach for you at this time. Be practical. Narrow down what your next steps will be in your assertiveness journey.

Remember that your choices are always tentative and subject to change with new circumstances and information. Stay your course, but remain flexible, making adjustments as needed. Setting goals for your own life can be an exciting process. As you take steps toward each goal, you’ll find a genuine sense of accomplishment in your progress. Pat yourself on the back as you achieve each step. Use your journal regularly to keep track.

Most important: let this be for you. Your goals needn’t please anybody else. Pay careful attention to your own needs; play your own game.