Chapter 11

There’s Nothing to Be Afraid Of

Courage is resistance to fear, mastery of fear, not absence of fear.

— Mark Twain

In any social situation, I felt fear. I would be anxious before I even left the house, and it would escalate as I got closer to a college class, a party, or whatever. I would feel sick to my stomach; it almost felt like I had the flu. My heart would pound, my palms would get sweaty, and I would get this feeling of being removed from myself and from everybody else.

— Quoted from National Institute of Mental Health

Many readers of Your Perfect Right — perhaps you too — find anxiety to be the most significant obstacle to greater assertiveness. “Sure,” you say, “I know how to express myself. I just get really uptight about doing it. The risks seem too great. I want people to like me.”

Microsoft co-owner Melinda Gates told Time magazine that her investor friend Warren Buffett — also a billionaire, of course, and famous for being a natural public speaker on financial matters — had to take extra pains to overcome his own fear of public appearances. Buffett, named by Time as one of “the most influential people in the world,” took the Dale Carnegie course in public speaking, says Gates, to get past his anxiety and to develop what has become one of his greatest skills.

Perhaps you find yourself perspiring, your heart racing, your hands icy as you anticipate a public appearance. Or you get those same feelings as you’re about to walk into a job interview. Or maybe you have avoided asking your boss for a raise because you fear the words will catch in your throat. Do you take the long way home so you don’t have to confront the neighbor who is always asking favors that you’re afraid to refuse?

Social anxiety , also known as social phobia , is the term psychologists use to label the fear of being judged by others or being embarrassed. Typical of such occasions would be speaking in front of a group or crowd (the most common fear), meeting new people, going to meetings or parties, performing or working when observed by others — in short, appearing in any situation in which one might be criticized, judged, or rejected.

You may not even be aware of the source of such fears. They may have resulted from childhood experiences — for example, well-meaning parents may have taught you to “speak only when spoken to.” Or classmates may have teased you when you stood up to make an oral report.

Or you may be one of the many who have the genetic predisposition to shyness and/or social anxiety that relatively recent research studies have shown to exist. Some people are born with the likelihood that they will be reticent or fearful in social situations. Yet, even for those whose social anxiety is inborn, it is possible to reduce the level of anxiety to a point where social situations are not so intimidating.

Learning to be assertive is one way to help reduce such fears. Still, when the level of anxiety is very high, it may be necessary to deal more directly with the anxiety itself. That’s the topic of this chapter.

To overcome fear, nervousness, anxiety, and stress about acting assertively, it’s necessary to determine what causes the reaction. Once you know what you are dealing with, you can learn methods to eliminate the fear. So we suggest you begin by tracing your fear. Narrow down exactly what causes you to feel afraid to express yourself assertively. Use your journal to record your reactions systematically, and keep track of what is causing your anxiety (fear) level to rise.

Finding Your Fears: The SUD Scale

Figuring out your own level of anxiety can help you put it in perspective and tackle it more effectively. An excellent aid for doing that is the subjective unit of disturbance , or SUD. Developed by psychiatrist Joseph Wolpe and psychologist Arnold Lazarus, the SUD is a simple way to estimate just how anxious you feel in a situation. You can construct your own “anxiety scale” by rating your feelings of anxiety from 0 SUDs (completely calm) to 100 SUDs (the worst anxiety you can imagine).

Because anxiety has physical elements, you can become aware of your degree of disturbance in a situation by “tuning in” to your body’s indicators: heart rate (pulse), breathing rate, coldness in hands and feet, perspiration (particularly in hands), and muscle tension. There are others, but most of us usually are not aware of them. Biofeedback training — the electromechanical measurement and reporting of specific bodily functions, such as heart rate, skin conductivity, muscle tension, and breathing — is sometimes used to allow people to learn when they are relaxed or anxious, since it offers an automated monitor of physical indicators.

Try this: get yourself as relaxed as you can right now — lie flat on the couch or floor or relax in your chair, breathe deeply, relax all the muscles in your body, and imagine a very relaxing scene (such as lying on the beach or floating on a cloud). Allow yourself to relax in this way for at least five minutes, paying attention to your heartbeat, breathing, hand temperature and dryness, and muscle relaxation. Those relaxed feelings can be given a SUD scale value of 0, representing near-total relaxation. If you did not do the relaxation exercise but are reading this alone relatively quietly and comfortably, you may consider yourself somewhere around 20 on your SUD scale.

At the opposite end of the scale, visualize the most frightening scene you can imagine. With your eyes closed, picture yourself narrowly escaping an accident or being near the center of an earthquake or flood. Pay attention to the same body signals: heart rate or pulse, breathing, hand temperature and moisture, and muscle relaxation. These fearful feelings can be given a SUD scale value of 100 — almost totally anxious.

Now you have a roughly calibrated comfort/discomfort scale that you can use to help yourself evaluate just how anxious you are in any given situation. Each ten points on the scale represents a “just noticeable difference” up or down from the units above and below. Thus, 70 is slightly more anxious than 60 and by the same amount more comfortable than 80. (The SUD scale is too subjective to be able to define comfort level more closely than ten units.)

Most of us function normally in the range of 20–50 SUDs. A few life situations will raise anxiety above 50 for short periods, and on rare occasions, one can relax below 20.

The SUD scale can help you to identify those life situations that are most troublesome. Once again, being systematic in your observations of yourself can pay big dividends. The procedure described below shows a way to use the SUD scale to develop a “plan of attack” against your fears.

List and Label Your Fears

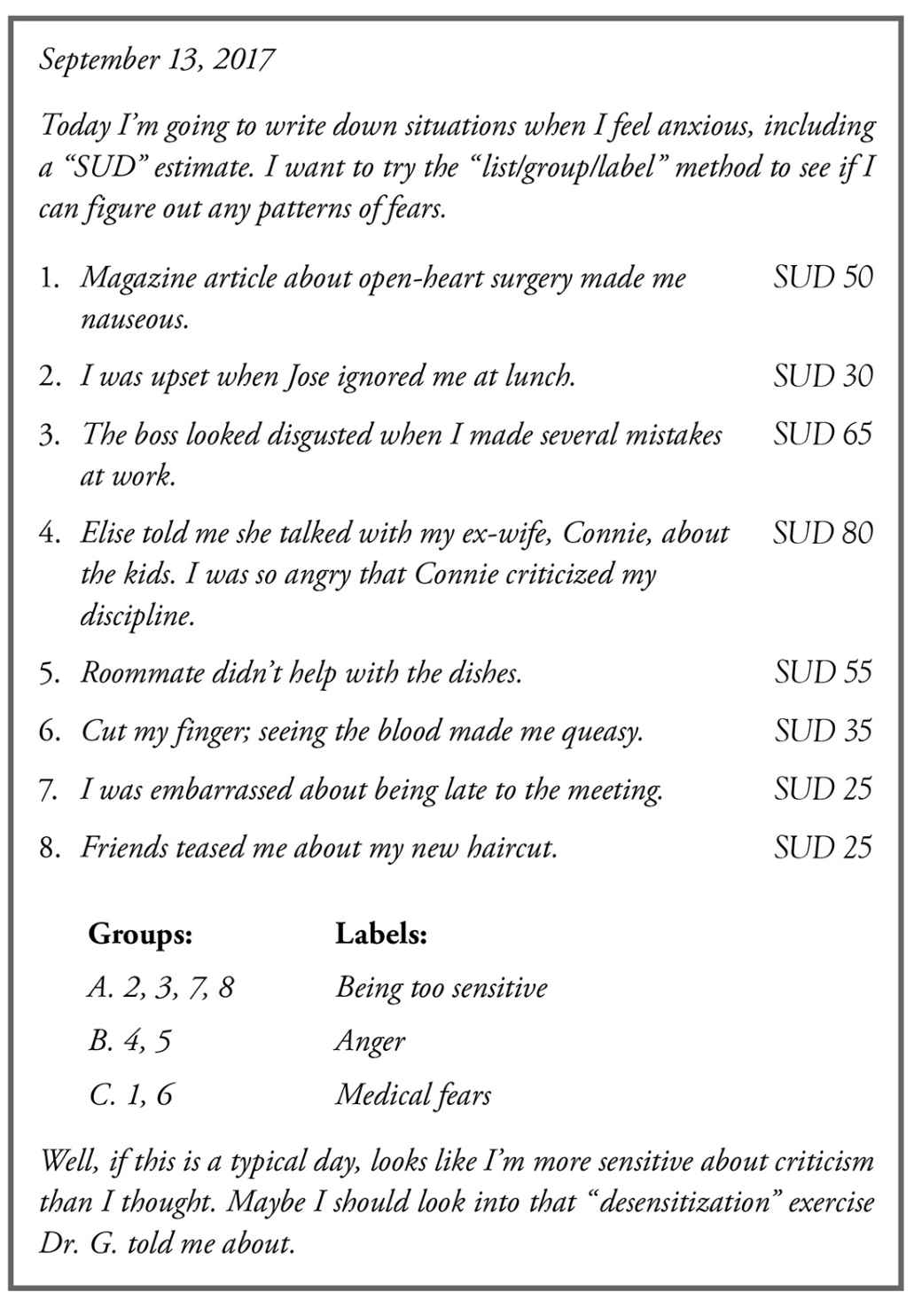

A method developed in the field of creative writing — list/group/label — is another helpful tool you might want to use as you address questions of anxiety.

Start by recording or listing life situations when you feel fear or anxiety. Use some space in your journal to list all your reactions that hinder your assertiveness, including the situation or event involved, people, circumstances, and other factors that contributed to your reaction. Assign a SUD value, as described in the previous section, to each of the items on your list.

Next, find the reactions on your list that are similar, those that seem to have a common theme, and group them together. Now see if you can label your groups, applying appropriate names to each grouping of anxiety-producing factors. Among your groups may be such common phobias as fear of snakes, spiders, heights, or enclosed places. Interpersonal fears are more likely to be the problem in assertiveness — fears of criticism, rejection, anger or aggression, or hurting the feelings of others.

You may find a grouping that centers on one or more of the situations given in the Assertiveness Inventory. Instead of a classic fear like rejection, you may simply experience a good deal of anxiety when standing in line or when facing salespeople. Perhaps people in authority scare you. Obviously, your assertiveness will not be optimum if your anxiety is already working against you beforehand.

Now, one more step in this analysis of your fears. In each labeled group, relist the items in order, according to the SUD scores you have assigned. Now you have a rough agenda, in priority order, for dealing with your anxieties. Usually, it is best to start working to reduce or overcome those that are most disturbing before you attempt to develop your assertive skills further.

The sample journal entry on page 128 will help make this process clearer.

We’re indebted to Patsy Tanabe-Endsley, who describes this system of listing, grouping, and labeling ideas in her book Project Write . We’ve adapted her system by simply substituting “fears or anxieties” for “ideas.”

Methods for Overcoming Anxiety

Now that you have carefully identified the anxieties that are inhibiting your assertiveness, you’ll want to begin a program to overcome them. There are many effective approaches. Since this topic is a book in itself, let us briefly describe some popular methods; then we’ll refer you to other resources for detailed information.

Systematic Desensitization

This approach, controversial and experimental when introduced more than fifty years ago, is another developed by assertiveness training pioneers Joseph Wolpe and Arnold Lazarus. Like assertiveness training, systematic desensitization is based on learning principles, asserting that you learned to be anxious about expressing yourself and you can unlearn it.

Since we know that it isn’t possible to be relaxed and anxious at the same time, the process of desensitization involves repeatedly visualizing an anxiety-producing situation while feeling deeply relaxed throughout the body. Gradually, with repeated exposure, the brain learns to “automatically” associate relaxation — instead of anxiety — with the situation.

In a therapeutic desensitization, you’ll first learn to relax your entire body completely through practicing a series of deep muscle relaxation exercises or through hypnosis. The anxiety-producing situation is then presented in a series of imagined scenes arranged in order from least to greatest anxiety, interspersed with a relaxing scene of your choice (again, such as lying on the beach or floating on a cloud).

You’ll imagine yourself in each scene and pay attention to the anxiety that results. After five to fifteen seconds, you’ll switch your visualization to your relaxing scene, relaxing once again. This procedure is repeated several times for each step of your hierarchy of anxious scenes. The repeated exposure to your anxiety while you are relaxed gradually reduces your fear in the anxious situation.

The intricacies of the procedure are more complicated, but that’s the essence of systematic desensitization. It has been proven effective for a wide range of fears, including phobic reactions to heights, public speaking, animals, flying, test taking, social contact, and many more.

Exposure Desensitization

Similar to the procedure for systematic desensitization described above, desensitization by gradual exposure to sources of anxiety in the real world is another proven strategy for overcoming anxiety.

A particularly vivid example of this treatment is demonstrated in the case of individuals who are working to overcome agoraphobia — a debilitating fear of “open spaces,” the marketplace, or social events. People with agoraphobia are asked to create a hierarchy similar to that for systematic desensitization (above), then to take very gradual steps of exposure to the feared situations — one step at a time — then back to a “safe” environment. With this repeated gradual exposure — never beyond the point of very mild anxiety — the client becomes able to confront and eventually to overcome the fear of being outside and among other people.

As with systematic desensitization, it is important to take only small steps and to build on success by repeating the low-anxiety steps one has already become desensitized to while progressing up the hierarchy to more anxious environments.

Such gradual real-world exposure procedures have been shown to be highly effective with a variety of anxiety-producing situations, including riding in or driving a car, being in high places, riding in elevators, entering school classrooms, taking public transportation, and attending social events. While it is possible for exposure to be self-administered, it is usually best conducted under the guidance of a trained therapist.

Diet, Exercise, and Sleep

In today’s world, there is never enough time. Try to cross the street at a busy but unlighted intersection. Cars, trucks, and buses fly by, everyone in a hurry, no one stopping for a pedestrian. We rush to work in the morning, often skipping breakfast, “the most important meal of the day,” just as Mom always told you! We rush out at lunchtime to meet a friend for a quick sandwich, to pick up the laundry, or to shop for a new cell phone. “Exercise” consists of scurrying across that intersection, running for the commuter train, or mowing 150 square feet of grass. For a lucky few, it may also include a round of golf or a couple of hours a week at a fitness club.

We know better, don’t we? We know that it’s vital to our well-being to eat well, exercise vigorously on a regular basis, and sleep soundly. Without those self-care systems, living life at today’s speed is certain to make us anxious!

Of course, diet, exercise, and sleep are not treatments for anxiety as much as they are preventions . If you eat a well-balanced diet, full of whole grains, fresh fruits, and vegetables with minimal fat and sugar, you’re going to be healthier than if you’re grabbing a fast-food snack or a grande latte on the way to work. (And keep in mind that the caffeine and sugar in that latte will keep you pumped up even if you don’t have any other reason to be anxious.) If you sleep soundly for something close to the recommended six to eight hours, you’re more likely to be refreshed — and less anxious — the next day. If you get plenty of heart- and muscle-healthy exercise, you’re going to feel better in every way, including in situations that might otherwise cause anxiety.

Here are some notable comments about exercise and mental well-being:

Exercise stimulates various brain chemicals, which may leave you feeling happier and more relaxed than you were before you worked out. You’ll also look better and feel better when you exercise regularly, which can boost your confidence and improve your self-esteem. Exercise even reduces feelings of depression and anxiety.

— The Mayo Clinic

Exercise reduces feelings of depression and anxiety [and] promotes psychological well-being and reduces feelings of stress.

— US Centers for Disease Control

Okay, enough of the parental lecture. But don’t take our word for it. Read the volumes of literature on the subjects offered by the American Heart Association, the Anxiety Disorders Association of America, the American Dietetic Association, and virtually every other recognized authority on health. To help sort out the confusing “facts” about nutrition, take a look at Dr. Andrew Weil’s Eating Well for Optimum Health .

While there is much agreement on these matters, it appears not to be “settled science.” The healthiest diet, for example, is still a matter of some controversy, and a new study of what works best for most people seems to come out almost every week — most of them focusing on weight loss. When it comes to what’s right for you , keep in mind that studies reported in the popular press almost always give us the results for most people in the study. That may or may not be the right thing for every individual — such as you.

Meditation, Breathing, Relaxation Training, and Mindfulness

Many books have been written on each of these topics, and we won’t be able to do them justice here. What’s important about meditation, breathing, relaxation, and mindfulness is that they have very positive and lasting effects far beyond their specific benefit as part of an anxiety treatment program.

The systematic practice of meditation is a powerful means of turning off the world around you for short periods in order to focus your attention on your body, your breathing, your thoughts, or your mental image of a most restful and contemplative place. Some folks balk at meditation because it sounds a bit mystical. It’s not, although the most widely used procedures have roots in Eastern philosophies. If it sounds strange or unusual, it’s because we so seldom allow ourselves to retreat from the pressures and distractions of the day into a quiet time. Most forms of meditation in Western societies are not based on mystical content and have been developed as a way of promoting physical and mental well-being.

There are dozens of forms of meditation, breathing, relaxation, and mindfulness practice, including progressive muscle relaxation (Edmund Jacobson), autogenic training (Johannes Schultz), relaxation (Ainslie Meares), relaxation response (Herbert Benson), biofeedback, and mindfulness-based stress reduction (Jon Kabat-Zinn). Among the remarkable findings from neuroscience is the strong evidence that both Zen meditation and mindfulness can actually rewire the circuitry of the brain!

It is widely recognized that anxiety and stress significantly contribute to a lack of physical health, and there is an increasing volume of mainstream medical research in this area. Hospitals, for example, often use meditation as a method of stress reduction for patients with a chronic or terminal illness or a depressed immune system.

Jacobson argues that since anxiety includes muscle tension, one can reduce anxiety by learning how to relax the tension. Benson, whose Institute for Mind Body Medicine is affiliated with Massachusetts General Hospital, describes the “relaxation response” as a complex of physiological changes that come with deep relaxation, including changes in metabolism, heart rate, respiration, blood pressure, and brain chemistry. Kabat-Zinn created the Center for Mindfulness in Medicine, Health Care, and Society at the University of Massachusetts Medical School, where intensive research has demonstrated the benefits of mindfulness meditation on reducing stress. (More on mindfulness in our discussion of anger in chapter 18.)

Treatment for Panic Attacks

If you are experiencing major anxiety attacks — panic at just the thought of a confrontation, for example, or for no apparent reason at all — you may need to undertake a systematic treatment program with a therapist.

Wisconsin psychologist and author Denise Beckfield has developed a program that helps clients to figure out what leads to their panicky feelings, thought patterns, and the resulting physical reactions: shaking, palpitations, dizziness, chills, nausea, chest pain, and the horrible sensation of losing control or “going crazy.” Beckfield also encourages examination of background aspects — such as genetics, personality traits, and early experiences — that may have lowered one’s anxiety threshold, as well as issues such as loss and anger that feed into panic attacks.

The good news is that the scary sensations not only do pass; in time, they can be made to disappear completely. Among the simple techniques suggested for panic patients are (1) to keep a journal to note panic episodes, record feelings at the time, and chart positive actions and successes; and (2) to learn and practice a controlled breathing exercise (“Stop, Refocus, Breathe”) — a remarkably effective technique in helping one to “chill out” quickly during anxious times.

If you suffer from full-blown panic attacks, you’re encouraged to see a psychologist or other qualified psychotherapist. If, however, your social anxiety leads to near-panic episodes, anxiety in specific situations, or chronic low-level anxiety, you can use self-help procedures to begin to take charge and stay calm as you face social encounters. Dr. Beckfield’s book Master Your Panic and Take Back Your Life is a good beginning.

Irrational Beliefs and Self-Talk

We grow up with lots of funny ideas, and as adults, we repeat those ideas until we talk ourselves sick. What kinds of “funny ideas”? Well, how about the idea that the world must treat us perfectly. Or that life should be fair. Or that if you don’t succeed at everything you do, you’re no good. We talked about some of these irrational thoughts in chapter 10. (You might want to review that material.) One unfortunate result of such ideas is that we upset ourselves unnecessarily, provoking anxiety, panic, depression, frustration, anger. We pay a high emotional price for believing impossible things about how the world should treat us, because the real world will never measure up to those ideals.

To counter these toxic notions and get back on a path to healthier thinking, we recommend the work of the late psychologist Albert Ellis, whose books and other works on rational emotive behavior therapy (see the reference section at the back of this book) will help you learn to dispute irrational thoughts in your life and replace them with realistic ideas that more closely resemble what life will likely present to you. Ellis’s sage advice, noted in chapter 8, is worth repeating here: “What troubles us in life is not what happens to us, but how we react to what happens.”

Assertiveness

We haven’t talked much about it in this book, but the fact is that renowned psychologist Arnold Lazarus and psychiatrist Joseph Wolpe originally devised assertiveness training as a treatment for anxiety . In laboratory research in South Africa in the 1960s, working on new treatments for anxiety in animals, they devised careful physiological measures and found that fearful animals became relaxed when the feared situation was paired with food, relaxation, or assertiveness.

Since you’ve been learning about assertiveness throughout this book, we needn’t pursue the topic further here, except to say that, particularly for those who are anxious because they are uncertain about their social skills, assertiveness training is well established as an effective treatment for social anxiety.

Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR)

Developed around 1990 by psychologist Francine Shapiro, eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) created a good deal of commotion early on because it seemed a bit “magical.” The name was derived from the original procedure, which involved moving the eyes from side to side repeatedly while remembering upsetting memories concerning past traumas or anxiety-provoking situations.

The introduction of EMDR provoked some controversy among mental health professionals, due primarily to the unusual “eye movement” requirement. Concern was also expressed about the apparent very rapid client response to the method and about Shapiro’s early demand that the method be employed only by practitioners she had personally trained.

Over time, research with EMDR found that the important element in reducing the disturbance is not the eye movement , but the alternating movement . A technological innovation used by many EMDR therapists involves a handheld electronic vibration device to stimulate the alternating movement.

The EMDR method has been effective in dealing with the anxieties and fears associated with behaving assertively, emotional confrontations, hurting others’ feelings, and being the center of attention. EMDR also has been shown to be helpful in overcoming the aftereffects of traumatic stress situations (such as physical or sexual abuse, war experiences, accidents, natural disasters, and dysfunctional family experiences) and in overcoming the guilt, fear, upset, faulty thinking, and anxiety that often result from traumatic experiences.

(Coauthor Michael Emmons was trained in EMDR therapy and has used it in his practice. He has been enthusiastic about the results and correctly predicted years ago that EMDR would gain widespread acceptance as a method for helping people overcome anxieties, fears, and traumas. It has done so, though it is still not universally endorsed.)

Medication

If you go to see your primary care physician or internist about anxiety, you’re very likely to get a prescription for an antianxiety medication. There is a host of such drugs on the market today. You’ve surely seen them advertised on television and online: “Ask your doctor if NoAnx is right for you!”

And you may well ask this question. If you’ve had a good relationship with a primary care doc for some time and anxiety is something new in your life, the doctor may be able to determine that it’s due to a chemical change and should be fought with appropriate chemical counteragents.

We don’t happen to believe that medication should be your first line of attack, however, unless the anxiety has come out of nowhere suddenly and there appears to be no likely suspect in your immediate life situation. We encourage you to consider first the other approaches we’ve described in this chapter.

If you do elect to go the route of meds, prepare yourself well to discuss prescriptions with your physician. Inform yourself. Do some homework on the variety of drugs available for anxiety and their side effects. Don’t simply accept the first one your doctor suggests, and by all means don’t believe the ads you see, hear, and read. Check carefully — before you fill a prescription — to determine that a recommended drug is really “right for you.”

Chances are your primary care physician will not have the time or expertise to do a thorough psychological workup. Primary care doctors are usually so busy — and the health care finance system allows them so little time with patients — that they simply write scripts for their favorites, the drugs that seem to work for most folks. Don’t settle for that. Ask why a particular drug is the best one for you.

If your doctor is unwilling to discuss these issues with you, use your assertiveness skills to deal with your need for information and a respectful, cooperative relationship. If your needs go unmet, consult another physician.

For detailed information about anxiety medications, we suggest you visit the authoritative websites of the National Institute of Mental Health and Mental Health America (both of which are listed as online resources at the back of this book).

Other Therapies for Anxiety

We’ve briefly discussed several proven approaches to dealing with anxiety, ones we know to be effective and are able to recommend. As you might guess, there are many more. Some therapists would have you spend years examining early childhood experiences and relationships with your parents and siblings. Others would put you in a highly stressful situation immediately (you might call it “sink or swim”). Among the many ideas other therapists often suggest for treating anxiety are psychoanalysis, acceptance and commitment therapy, Gestalt therapy, implosion therapy, hypnosis, and systemic family therapy.

One surprising application of technology to social anxiety takes us outside the realm of “therapy” and into cyberspace. A recent study in Taiwan reported that participating in massive multiplayer online role-playing games (MMORPGs) reduced players’ anxiety and improved their social relationships (Ho, Lin, and Lee 2015). And here we thought time spent online might be hurting social skills!

If you need special help overcoming anxiety about expressing yourself assertively, we suggest you examine the procedures we’ve discussed above and identify one that best fits your own circumstances and style. Start that process by doing some further reading. Two good books on the topic are The Stress Owner’s Manual by C. Michele Haney and Ed Boenisch and The Anxiety and Phobia Workbook by Edmund Bourne. Both books explore self-help procedures for anxiety and describe further resources available.

Once you commit to an intervention for your anxiety, expect to invest some time — probably several weeks — practicing your choice of the methods of anxiety relief, with or without a therapist. It took time for you to become anxious; it will take time to overcome it.

Summing Up About Anxiety

We don’t mean to discourage you with this discussion of anxiety about being assertive. On the contrary, most readers will find themselves able to handle their mild discomfort about self-expression without major difficulty. There are some of us, however, who do need some extra help in overcoming obstacles. Don’t be embarrassed or hesitant about asking for help just as you would seek competent medical aid for a physical problem. Then, when you’ve cleared up the anxiety obstacle, turn back to the procedures we suggest for developing your assertiveness.

Feelings of nervousness, anxiety reactions, and fear are common when thinking about and acting assertively. Often, practicing assertive responses will reduce these uneasy reactions to manageable levels. Practice will make assertion feel more natural to you. If you feel that you’re still too afraid, take another look at the systematic ways we’ve described in this chapter to identify and deal with the situations that trigger your fearful reactions.

Simply understanding a fear, while an important first step, is seldom powerful enough to reduce it significantly. Self-help methods that help eliminate or lower the fear to manageable levels are often successful. Professional therapy is recommended when your own efforts are not enough.

We called this chapter “There’s Nothing to Be Afraid Of.” Actually, life hands all of us situations we find fearful at times. What we want you to remember is that there are effective ways to deal with anxiety . If it’s a problem for you, we urge you to read this chapter again, learn as much as you can about your anxiety, and seek out methods — including professional therapy, if necessary — that will help you overcome it.