Chapter 18

Anger 102: What You Can Do About It

Hello, my little anger. I will take good care of you.

— Thich Nhat Hanh

“ I’m confused. On the one hand you’re saying, ‘It’s not healthy to express anger.’ On the other, you say, ‘You need to resolve your anger; don’t let it become chronic.’ Which is it? Do we show anger or not? Are we simply to ‘take a deep breath’ and forget the feelings? Is it really healthiest not to even talk about our anger?”

We warned you that there are no simple answers. Human emotions are incredibly complex, and there aren’t any “one-size-fits-all” solutions. There are some guidelines, however, and this chapter is devoted to helping you sort out the complexities.

To begin our examination, let’s go back to the Williamses and their book Anger Kills and note their guidelines for deciding how to respond to angry feelings:

- “Is the matter worth my continued attention?”

- “Am I justified?”

- “Do I have an effective response?”

They’re suggesting that when you begin to feel angry, you take a moment (recall Mark Twain’s advice: “count four”) to consider just how big a deal this really is and how right you really are. (In chapter 22, we provide a detailed guide to choosing when to take assertive action.) Then, if you decide that your angry feelings must be expressed, do so assertively, without hurting someone else (physically or emotionally) in the process.

Expression of your anger is not your only choice, of course. Let’s consider some alternatives.

Take Good Care of Your Anger

Anger, as Vietnamese Zen master Thich Nhat Hanh suggests in the epigraph on the preceding page, is a part of us, deserving of our care. Not that it’s a good thing, but it’s a normal human thing. Nhat Hanh advocates mindfulness as an alternative to expression of anger. Accept it, own it, embrace it, recognize it as your “little anger” — a part of you — and use that recognition as a starting point for self-acceptance.

Meditation and mindfulness provide a means to undo the knots that anger creates in us. “Breathing in, I know that anger is in me. Breathing out, I am taking good care of my anger,” says Nhat Hanh. Slowing down, breathing, focusing on the present moment, ignoring what went before (regret) and what may come next (worry), treating yourself with compassion — all these self-care behaviors can allow you to take care of your little anger, rather than allowing your anger to take over you.

Dr. Jon Kabat-Zinn, whose work with mindfulness we noted in chapter 11, says, “Every time we get angry we get better at being angry and reinforce the anger habit.” Might it be time to give up your anger habit?

Accept It

Most approaches to handling anger, including our own presented later in this chapter, assume that we can take action to overcome or conquer or manage our anger. Mainstream schools of therapy consider psychological health to be “normal” and argue that emotional pain — such as anger, anxiety, and depression — should be treated and eliminated.

Acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) is a relatively new cognitive approach (created by psychologist Dr. Steven Hayes in the late twentieth century) that builds on mindfulness and offers a way to deal with anger by not dealing with it. (Say what? )

ACT has adopted the somewhat controversial assumption that psychological pain is a normal human condition, not a malfunction to be shunned, avoided, or overcome. This approach accepts and embraces — rather than attempting to avoid or cure — emotional discomfort as a part of who we are. ACT combines acceptance and mindfulness with commitment to strategies for health-promoting behavior change. The procedures follow the mindfulness meditation path of attending to the present moment, calming the mind, breathing slowly, and — as the well-known serenity prayer advises — accepting “the things I cannot change,” including emotional pain and discomfort.

University of Washington psychologist Marsha Linehan’s dialectical behavior therapy (DBT) is a similar adaptation of cognitive behavioral therapy methods merged with mindfulness. DBT, which grew from Dr. Linehan’s work in cognitive behavioral therapy (including some important contributions to assertiveness training), also emphasizes acceptance. Linehan recognized that, for many patients who were experiencing significant, debilitating emotional pain, changing their thoughts or working through a behavior change procedure was not bringing relief. Her “dialectical” approach helps them to balance acceptance and change, utilizing skills of mindfulness, distress tolerance, interpersonal effectiveness (aka assertiveness), and emotion regulation. Carried out properly by a qualified psychotherapist after accurate diagnosis, DBT can be a powerful system for dealing with destructive anger and other significant emotional difficulties.

Work It Out

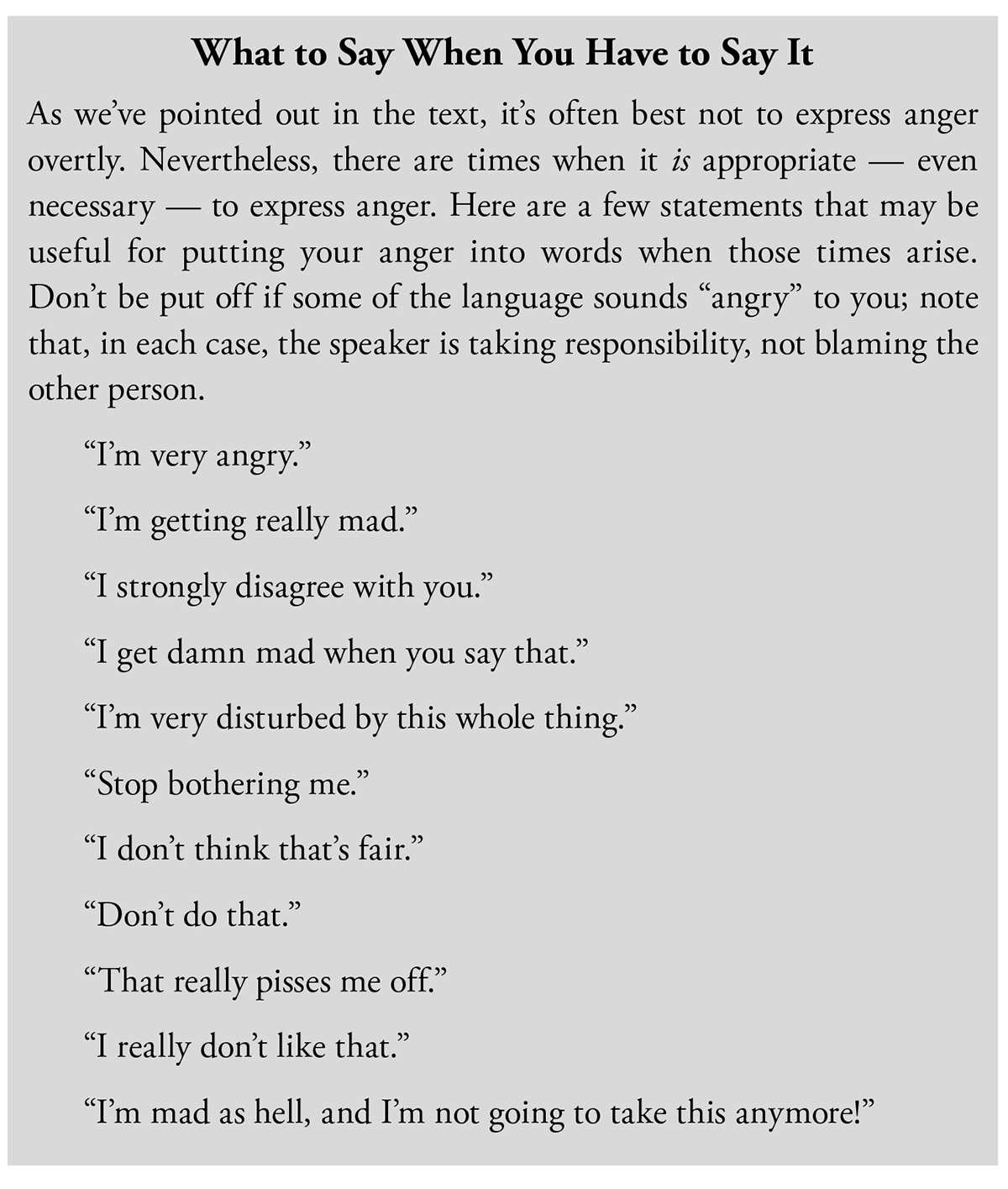

Honest and spontaneous expression aimed at resolving the disagreement can help to prevent inappropriate and destructive anger later and may even achieve your goals at the outset. When you do choose to express your anger, one of the most constructive steps you can take is to accept responsibility for your own feelings . Keep in mind that you feel the anger, and that doesn’t make the other person “stupid,” “an S.O.B.,” or the cause of your feeling. (The sidebar on page 209 has some ideas for language that may help you say what you’re feeling in an assertive way.)

The central objective of effective anger expression should be to achieve some resolution of the problem that caused the anger. “Getting the feelings out” — even when that’s needed — only sets the stage. Working out the conflict with the other person, or within yourself, is the all-important step that makes the difference. That doesn’t mean pounding a pillow until you are exhausted; it means working out some resolution of the issue yourself — through relaxation, forgiveness, acceptance, attitude change, negotiation, constructive confrontation, or psychotherapy.

If you take action that doesn’t help you to cope with or to resolve the problem, your anger may actually increase, whether you’ve expressed it or not . So, focus your energy on problem-solving actions. Work to resolve the issue through assertive negotiation of solutions with the person with whom you’ve been angry. If direct resolution is not possible, find satisfaction within yourself (perhaps with the aid of a therapist or trusted friend). In either event, don’t stop by saying, “I’m mad as hell!” Follow through with “and here’s what I think we can do about it.”

Keep your anger in perspective. Don’t take it too lightly or too seriously. Learn what triggers it, teach yourself to “lighten up” in the face of situations that usually set you off, and develop effective ways to deal with it when it comes. Focus on working out your issues.

Fortunately, there are some really helpful procedures that are of proven value. As it so happens, they fall naturally within three general guidelines: (1) minimize anger in your life; (2) cope before you get angry; and (3) respond assertively when you decide it’s worth it to express your anger.

Minimize Anger in Your Life

Our first ten steps are borrowed from the Williamses’ recommendations in Anger Kills (We told you we like their work!):

- Improve your relationships with others through community service, tolerance, forgiveness, and even caring for a pet. Brain research has shown that good social support systems reduce the brain’s production of cortisol (bad for the heart), boost the immune system (good for everything), help good moods, and limit bad moods.

- Adopt positive attitudes toward life through humor, belief in something beyond yourself, and acting as if today is your last day.

- Avoid overstimulation from chemicals, work stress, noise, and traffic.

- Listen to others. Practice trusting others.

- Have a confidant. Make a friend and talk regularly, even before you feel stress building up.

- Laugh at yourself. You really are pretty funny, you know. (It goes with being human.)

- Meditate. Calm yourself. Get in touch with your inner being. Focus your self-awareness on this moment, not what happened before or what may come after.

- Increase your empathy. Consider the possibility that the other person may be having a really bad day.

- Be tolerant. Can you accept the infinite variety of human beings?

- Forgive. Let go of your need to blame somebody for everything that goes wrong in your life.

To the Williamses’ ten, we add three of our own tenets to this section:

- Work toward resolution of problems with others in your life, not “victory.”

- Keep your life clear! Deal with issues when they arise, when you feel the feelings, not after hours, days, or weeks of “stewing” about them. When you can’t deal with things immediately, arrange a specific time when you can and will.

- Use alcohol in moderation; controlled substances not at all. Alcohol and drugs may offer a temporary escape from anxiety, depression, and the stresses of life, but they lead away from problem solving. Moreover, they reduce inhibitions and may contribute to inappropriate and unnecessary anger expression.

Cope Before You Get Angry

Anger is a natural, healthy, nonevil human emotion, and despite our best efforts to minimize its influence in our lives, all of us will experience it from time to time, whether we express it or not. So, in addition to the steps above, you’ll want to be prepared before anger comes:

- Remember that you are responsible for your own feelings. You can choose your emotional responses by the way you look at situations. As psychologists Gary McKay and Don Dinkmeyer put it, “how you feel is up to you.”

- Remember that anger and aggression are not the same thing! Anger is a feeling. Aggression is a style of behavior. Anger can be expressed assertively; aggression is not the only alternative.

- Get to know yourself. Recognize the attitudes, environments, events, and behaviors that trigger your anger. As one wise person suggested, “Find your own buttons, so you’ll know when they’re pushed!”

- Take some time to examine the role anger is playing in your life. Make notes in your journal about what sets you up to get angry and what you’d like to do about it.

- Reason with yourself (another good idea from the Williamses). Recognize that your response will not change the other person. You can change only yourself.

- Deflect your cynical thoughts. Learn effective methods for thought stopping, distraction, and meditation (ideas in chapters 10 and 11).

- Don’t “set yourself up” to get angry. If your temperature rises when you must wait in a slow line (at the bank, in traffic), find alternate ways to accomplish those tasks (bank online, find another route to work, use the time for problem solving).

- Learn to relax. Develop the skill of relaxing yourself and learn to apply it when your anger is triggered. You may wish to take this a step further by “desensitizing” yourself to certain anger-provoking situations (review chapter 11 for more on desensitization).

- Develop several coping strategies for handling your anger when it comes, including deep breathing, meditation, mindfulness, acceptance, relaxation, physical exertion, stress inoculation statements, and working out resolution within yourself.

- Save your anger expression for when it’s important. Focus instead on maintaining good relationships with others.

- Develop and practice assertive ways to express your anger, so these methods will be available to you when you need them. Follow the principles you’ve learned in this book: be spontaneous when you can; don’t allow resentment to build; state your anger directly, without accusing or blaming the other person; avoid sarcasm and innuendo; use honest, expressive language; let your posture, facial expression, gestures, and voice tone convey your feelings; avoid name-calling, put-downs, physical attacks, one-upmanship, and hostility; and work toward resolution.

Now you’ve developed a healthy foundation for dealing with angry feelings. You’re ready to proceed to the next section, which will help you handle your anger when it comes.

Respond Assertively When It’s Worth It to Express Your Anger

- Take a few moments to consider if this situation is really worth your time and energy and the possible consequences of expressing yourself.

- Take a few more moments to decide if this situation is one you wish to work out with the other person or one you will resolve within yourself.

- Apply the coping strategies you developed in step 22 above and those listed at the end of the chapter.

If you decide to take action:

- Make some verbal expression of concern (assertively). Focus on I-messages or I-statements (see chapter 8 and the sidebar on the following page for some helpful ideas).

- “Schedule” time for working things out. Do it spontaneously if you can; if not, arrange a time (with the other person or with yourself) to deal with the issue later.

- State your feelings directly. Use the assertive style you have learned, with appropriate nonverbal cues (for example, if you are genuinely angry, a smile is inappropriate).

- Accept responsibility for your feelings. You got angry at what happened; the other person didn’t “make” you angry.

- Stick to specifics and to the present situation. Avoid generalizing. Don’t dig up the entire history of the relationship.

- Work toward resolution of the problem. Ultimately, you’ll resolve your anger only when you’ve done everything possible to resolve its cause.

When Someone Else Is Angry with You

Okay, now you have a road map for dealing with your own anger. But one of the most important needs expressed by assertiveness trainees is for ways to deal with the anger of others . What can you do when someone is furious and directing her full hostility at you?

Try these steps:

- Allow the angry person to express the strong feelings.

- Respond only with acceptance at first. (“I can see that you’re really upset about this.”)

- Take a deep breath and try to stay as calm as possible.

- Offer to discuss a solution later, giving the person time to cool off. (“I think we both need some time to think about this. Let’s talk about it tomorrow.”)

- Take another deep breath.

- Arrange a specific time to pursue the matter.

- Keep in mind that no immediate solution is likely.

- Follow the conflict-resolution strategies described below when you meet to follow up.

Thirteen Steps to Effective Conflict Resolution

How can we improve the process of resolving angry conflict between people or groups? Most of the principles are parallel to the methods of assertiveness, and many overlap with our discussion earlier in this chapter of ways to deal with anger.

Conflict is more easily resolved when both parties want to work things out, of course. Here is a set of proven guidelines for those who are willing to try:

- Act honestly and directly toward each other.

- Face the problem openly rather than avoiding or hiding from it.

- Avoid personal attacks; stick to the issues.

- Emphasize points of agreement as a foundation for discussion of points of argument.

- Employ a “rephrasing” style of communication to be sure you understand each other. (“Let me see if I understand you correctly. Do you mean… ?”)

- Accept responsibility for your own feelings. (“I am angry!” not “You made me mad!”)

- Avoid a “win-lose” position. The attitude that “I am going to win, and you are going to lose” will more likely result in both losing. If you stay flexible, both can win — at least in part.

- Gain the same information about the situation. Because perceptions so often differ, it helps to make everything explicit.

- Develop goals that are basically compatible. If you both want to preserve the relationship more than to win, you have a better chance.

- Clarify the actual needs of both parties in the situation. You probably don’t need to win . You do need to gain some specific outcome (behavior change by the other person, more money, and so on) and to retain your self-respect.

- Seek solutions rather than deciding who is to blame.

- Agree upon some means of negotiation or exchange. You’d probably agree to give in on some points if the other person would too.

- Negotiate toward a mutually acceptable compromise, or simply agree to disagree.

Add It Up: 33 + 8 + 13 = 4 — Keys for Coping with the Anger in Your Life

Almost everybody has trouble with anger, and as we’ve shown, it’s not easy to deal with this complex emotion. There are some things that help, however. We’ve offered lots of lists in this chapter, but we can boil it down for you. If anger is a problem in your life, you’ll want to go back and review the “fine print” above.

Meanwhile, the equation above is not a typo. Here are four key guidelines to remember:

- Minimize the anger in your life.

- Cope before you get angry.

- Be assertive when it’s important to express your anger.

- Work to resolve conflict whenever it occurs.