John Catterall Leach was born on 1 September 1894 at Clevedon, Somerset, the only son of Reverend and Mrs Charles Rothwell Leach. Clevedon was a tiny seaside resort on the Severn Estuary. It was, perhaps, best known for Clevedon Court, part of which was believed to be well over 500 years old. Stephen Lacey, the well-known garden writer, described Clevedon Court and its environs:

This is an ancient habitation. Remains of a Roman dwelling have been uncovered here, and the Great Hall and Tower were already standing when Sir John de Clevedon built the present manor house with its erratic roofline, and thick buttressed walls c.1320.1

It is a safe assumption that other features of Clevedon held much more allure for Jack Leach as a young boy than did the cold, austere walls of Clevedon Court. Clevedon is located where two ranges of hills meet. One range extending north to Portishead slopes to steep cliffs along the shore. The footpaths that meandered through this range provided Jack with endless opportunities to explore, but the dominant feature of Clevedon was the sea. As a schoolboy he soon learned that the sea defined the British Isles and connected the British Empire; that the sea was a barrier to Britain’s ancient foes. Indeed, this rudimentary knowledge of the sea’s vital role in the life of his country was the beginning of his understanding of the Royal Navy’s raison d’être.

In that era most British boys were intrigued by ships. Jack Leach was no exception and it can be said that his interest was more serious than most. The two largest ports on the Severn Estuary were Bristol and Cardiff. In the last years of the nineteenth century there were still plenty of sailing boats to be seen, but they were mainly privately owned yachts. The era of the British tea clipper, somewhat smaller but faster than the Yankee clipper, had already passed. Of all the British tea clippers, the most famous was Cutty Sark. This three-masted sailing ship was launched at Dumbarton, Dunbartonshire in 1869. She had a varied career as a commercial vessel before being converted into a training ship. She has been saved for posterity and is now in permanent dry dock at Greenwich. At some point in his childhood Jack Leach surely read about Cutty Sark and her journeys to the exotic Far East.

It goes without saying that Jack would have seen illustrations of HMS Victory, the most famous ship in the history of the Royal Navy. It is highly likely that he would have read a boy’s life of Lord Horatio Nelson, the Royal Navy’s greatest hero. John Keegan has written, ‘The artefacts and memorials of sea power are warp to the woof of British life. HMS Victory, cocooned in her dry dock at Portsmouth, is an object as much visited by British schoolchildren as the manuscript of their constitution by American.’2 It is likely that he was taken to Portsmouth just to see HMS Victory.

The ships that he saw most often were pleasure craft coming from Bristol and cargo ships out of Cardiff. Eventually Cardiff would be the largest port in the world for the export of coal. The first time in his life that Jack Leach saw a Royal Navy ship with her white ensign rippling in the breeze is unknown, but it would have made a lasting impression.

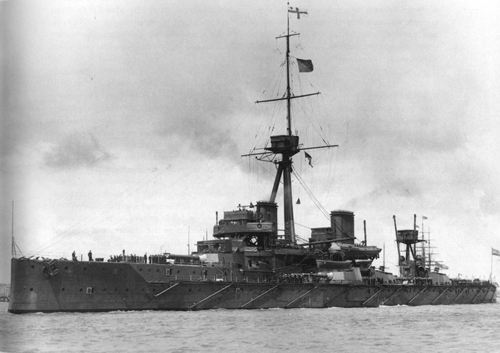

Dreadnought is a great name in the annals of the Royal Navy. There were nine Royal Navy ships that bore that name including the fifth Dreadnaught, a three-decker of 98 guns that fought with Nelson at Trafalgar. When she was completed in 1906 the sixth HMS Dreadnought represented the latest in battleship design and construction.

[She was] a British battleship of the early 20th century that established the pattern of the all-big-gun warship that dominated the world’s navies for nearly 40 years. Completed in 1906 ‘the Dreadnought’ had four propellers driven by steam turbines and displaced 21,845 tons. She was capable of a speed of 21 knots (24 miles per hour) and mounted ten 12-inch guns in five turrets.3

When Dreadnought was launched at Portsmouth on 9 February 1906, Jack Leach was five months beyond his eleventh birthday. All of England knew that HMS Dreadnought would be launched that day. The First Sea Lord, Jackie Fisher, planned an elaborate celebration to which he invited King Edward VII. The excitement and exaltation of that day have been marvellously recreated by Robert K. Massie in his book, Dreadnought.

King Edward, wearing his uniform of Admiral of the Fleet with its cocked hat and his blue ribbon of the Order of the Garter, left the yacht at eleven-fifteen a.m. and boarded his train for the short trip through the yard. The death of his father-in-law had curtailed some of the planned display, but the King’s train nevertheless passed between solid lines of sailors and marines along a route which included four triumphal arches draped with naval flags and scarlet bunting. At eleven-thirty the train arrived beneath the wooden platform and the King climbed stairs lined with red and white satin to find himself in an enclosure surrounded by admirals, government officials, a naval choir, members of the press, and all the foreign naval attachés, senior among them Rear Admiral Carl Coeper of the Imperial German Navy. Over their heads loomed the bow of the Dreadnought, garlanded with red and white geraniums.

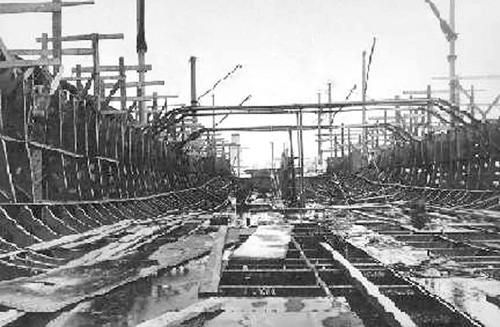

The construction of HMS Dreadnought in the Royal Dockyard at Portsmouth. (Courtesy of Imperial War Museum)

The completed HMS Dreadnought, which made all other battleships obsolete. (Courtesy of Imperial War Museum)

Fisher was irrepressible. Standing next to the King, he was seen continuously gesturing and describing features of the ship. The Bishop of Winchester began the service with the 107th Psalm: ‘They that go down to the sea in ships, that do business in great waters; these see the works of the Lord and his wonder, in the deep,’ and ended it by raising his hand to bless the ship and all who would sail in her. When the last blocks had been knocked away and the Dreadnought was held only by a single, symbolic cable, the King plucked a bottle of Australian wine from a nest of flowers before him and swung it against the bow. The bottle bounced back. Again his Majesty swung and this time the bottle shattered and wine splashed down the steel plates. ‘I christen you Dreadnought!’ cried the King. Then, taking a chisel and a wooden mallet made from the timbers of Nelson’s Victory, he went to work on the symbolic rope holding the ship in place. This time, one stroke did the job. The great ship stirred. Slowly at first, then with increasing momentum, she glided backwards down the greased building way. A few minutes later the giant hull floated serenely on the water, corralled by a flotilla of paddle tugs. The band played ‘God Save the King,’ the crowd gave three cheers, and His Majesty descended the steps.4

If young Leach did not read the newspaper accounts of HMS Dreadnought’s launching, he certainly heard about it from his father. The reaction of an eleven-year-old English boy to such an event can be fairly guessed. He would have taken enormous pride in the Royal Navy and his country. The long range effect of this event on Jack Leach’s life is less easily gauged. Perhaps, at the very least the introduction of a new class of battleship into the Royal Navy, which ensured that Great Britain would retain her naval supremacy, was a factor in Jack Leach’s decision to enter the Royal Naval College, Osborne, at an early age.