Jack Leach commenced his naval career at the Royal Naval College, Osborne. He was then only thirteen. The transition from family life at Clevedon to the life of a naval cadet at Osborne could not have been easy. Parental visits were not encouraged and he seldom if ever saw them during his time at the college.

Osborne, located on the Isle of Wight, had been a favourite home of Queen Victoria, second only to Balmoral. It was at Osborne that the Queen died on 22 January 1901. She had hoped that her eldest son would make Osborne his official residence; he chose to give the whole of the Osborne Estate to the nation while retaining considerable control over its use. In 1902 or early 1903 ‘that erratic naval genius, Admiral Sir John Fisher, then Second Sea Lord and in charge of personnel … suggested to King Edward that use might be made of portions of the Osborne Estate for a junior Naval College.’5 Fisher quickly won King Edward VII’s approval. Construction and conversion work commenced in March 1903. On 4 August of the same year the buildings were formally opened by the King accompanied by the Prince of Wales. It is interesting to note that there are striking parallels in the careers of Captain Leach and Admiral of the Fleet Lord Fisher, better known to the lower deck as Jackie Fisher. At only 40 Fisher was appointed Captain of the newest and most powerful vessel in the Royal Navy, HMS Inflexible; at 46 Leach was appointed Captain of HMS Prince of Wales, then also the newest and most powerful battleship. At 45 Fisher had become Director of Naval Ordnance; at the same age Leach received the appointment. Later the redoubtable Fisher would be twice appointed First Sea Lord. Certainly Leach would never have compared himself to Fisher; yet in early 1941 Leach had achieved an ascendancy that bode well for the future. He was by nature unassuming, but amongst his contemporaries there were more than a few who were sure that his promotion to Flag Rank was only a matter of time.

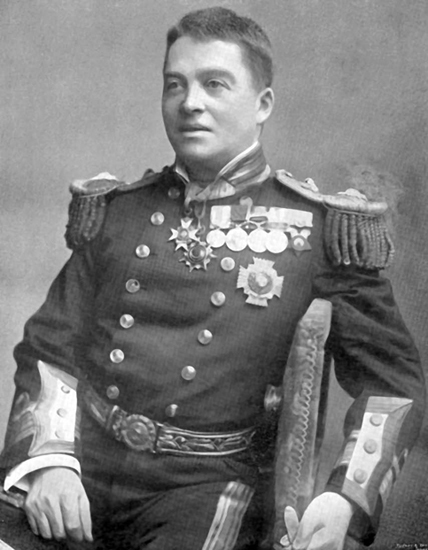

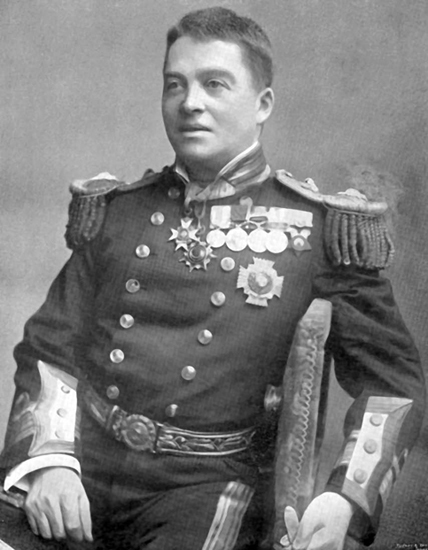

John ‘Jackie’ Fisher, later First Sea Lord as a Rear Admiral in the early 1890s. (Courtesy of Fisher Family Archives)

Cadet John C. Leach entered the Royal Naval College in 1907 as a member of the Exmouth Term. He came into contact with Prince Edward, later King Edward VIII, who was a fellow member of the Exmouth Term. Edward’s younger brother, Prince Albert, would enter Osborne two years later. Almost exactly eighteen years after Prince Albert entered Osborne he would spend over four months in the battle-cruiser HMS Renown on a round the world voyage, the highlight of which was a Royal Tour of Australia. On that voyage his naval liaison officer was Lieutenant Commander John C. Leach.

Cadet Leach was under a commanding officer who was responsible for discipline and naval instruction and a headmaster who was responsible for his academic studies. These two gentlemen, important though they were, did not have the same degree of influence on his life as the Term Officer. There were only six term officers picked from the wardrooms of the entire Navy. They were senior lieutenants of about 26 or 27. It has been said of them that they moulded the character of the cadets in their charge. Amongst their other duties they organised games and dealt out punishments. Such was the awe in which they were held by the cadets that they were considered demi-gods. Leach was also assigned a tutor who kept close track of his academic progress.

Cadet Leach’s two years at Osborne passed with good progress in both his naval instruction and his academic studies. When he left Osborne, he was well prepared for Dartmouth. Dartmouth, the full name of which is the Britannia Royal Naval College, is situated north of the town of Dartmouth on the side of a steep hill where it commands a magnificent view of the River Dart before it reaches the sea. The principal structure, designed by a distinguished architect, Sir Aston Webb, has been called ‘a masterpiece of Edwardian Architecture’.6 Dartmouth, which had been founded two years after Osborne, was a much more serious college and for good reason. In less than three years the cadets at Dartmouth would become midshipmen who would serve in ships of the Royal Navy in all of the exigencies of war. Naval Cadet John C. Leach now wore the regulation full-length naval overcoat instead of the short reefer jacket that he had worn at Osborne. He became conscientious in his dress and wore his uniforms with pride in himself and in the hallowed traditions of a navy that was second to none.

There is a total lack of archival documents about Cadet Leach’s career at Osborne; however, there is solid documentation about his career at Dartmouth. While it does not provide a comprehensive record of his life at the college, there are clear indications of his progress as a cadet and prowess on the athletic field. The Summer 1909 issue of Britannia Magazine published the term order of merit for the Exmouth Term. Leach was 28th out of a class of 61. He was well ahead of Prince Edward of Wales who was 49th. It was, however, on the playing fields of Dartmouth that he truly excelled.

The same issue of Britannia Magazine contains a photograph of Dartmouth’s First Eleven. J.C. Leach is standing in the second row. He is wearing white flannel trousers, white boots, a dark single breasted jacket and his college scarf. Leach was approaching his fifteenth birthday, although he looked younger. The magazine also contains a full account of a cricket match in which Leach participated as a bowler. The heading reads ‘Britannia RN College (cadets) v. Exeter School.’ In addition to Leach the following individuals are mentioned:

Harries, the Captain for Dartmouth and a fieldsman

Bulleid, a batsman for Exeter

Stanton, a bowler for Dartmouth

Twysden, a bowler and fieldsman for Dartmouth

Brown, a bowler for Dartmouth

Clow, a batsman for Exeter

The account of this match begins with a statement of victory. ‘This match was played on our ground on Saturday, July 3rd and resulted in a very easy win for us by seven wickets.’7 The writer continues:

Leach started from the stables end, and off his first ball Harries might have caught Bulleid in the deep field, but he misjudged the catch. … With the score at 50, Harries changed the bowling (this might, with effect, have been done before), Stanton and Twysden taking the place of Brown and Leach. … Then Leach, who had gone on again just before, took all before him, another excellent though rather lucky catch by Twysden at mid-on getting rid of Clow. … After the second wicket fell, our fielding was excellent, but it is a bad sign for fielding to get slack when wickets are not falling. Leach took six for 90, Brown three for 60, and Stanton one for 15.8

Leach did not bat.

The Summer 1910 issue of Britannia Magazine contains a personal description of the better members of Dartmouth’s cricket team. The heading reads, ‘First Eleven Characters.’9

Leach … Has bowled admirably throughout the season. Bowls fewer loose balls than formerly, and has developed a good though obvious off-break. Is a poor and timid field. As a bat has few strokes, but can be relied upon to keep his end up.10

There is no record of how 15-year-old Leach reacted to the assertion that he was ‘a poor and timid field’, but one can well imagine.

Leach’s ‘passing out’ from Dartmouth was in April 1911. Earlier that year he had shown much promise in the game of racquets. In the open singles he won four straight games before losing a hard-fought game to Lindsell in the finals 15–4, 8–15, 15–10, 15–6. Then he and Lindsell teamed up in the handicap doubles to win three straight games before winning the finals 15–8, 18–13, 18–13.

Dr Jane E. Harrold, Archivist and Deputy Curator of Britannia Museum, Britannia Royal Naval College, has kindly verified that ‘J.C. Leach joined Dartmouth from Osborne, in May 1909, passing out in April 1911. He was a member of the Exmouth Term together with HRH the Prince of Wales.’11 Dr Harrold is the co-author of the admirable book, Britannia Royal Naval College 1905–2005, A Century of Officer Training at Dartmouth. She and Dr Richard Porter have given their readers a vivid description of what Cadet Leach, age sixteen, experienced on the day he passed out:

The culmination of the young officers’ training at Dartmouth is the Passing Out Parade. Traditionally these were held three times a year at the end of each term. The ‘Passers Out’ would be inspected on the parade ground, followed by a slow march up the steps and into the front door of the College. The door would be slammed shut, and the young officers who have passed out toss their caps into the air to a resounding cheer.12

Before he was entitled to wear the dirk and patches of a midshipman, Leach was required to spend up to six months in a cadet training ship. There he learned the practical aspects of seamanship and the basic duties of junior officers in ships of the Royal Navy. His training ship was the 9800-ton armoured cruiser HMS Cumberland whose most conspicuous features were her three very tall funnels. This would not be the last time that Leach served in a ship named Cumberland. The next time he would be her Captain.

By 1911 the sands of peacetime were rapidly running out. It is not easy to pinpoint the start of the naval race between Britain and Germany, but it was evident on 3 January 1909. On that day Reginald McKenna, the First Lord of the Admiralty, who had become gravely alarmed at German progress in battleship construction, wrote to Prime Minister Asquith:

My dear Prime Minister:

… It seemed to me that an examination of the German Naval Estimates might prove helpful in showing how far Germany is acting secretly and in apparent breach of her law. … I am anxious to avoid alarmist language but I cannot resist the following conclusions which it is my duty to submit to you:

1) Germany is anticipating the shipbuilding programme laid down by the law of 1907.

2) She is doing so secretly.

3) She will certainly have 13 big ships in commission in the spring of 1911.

4) She will probably have 21 big ships in commission in the spring of 1912.

5) German capacity to build dreadnaughts is at this moment equal to ours.

The last conclusion is the most alarming, and if justified would give the public a rude awakening should it become known.13

After a furious debate in Parliament a censure motion of Balfour was defeated 353 to 135. This authorised the Admiralty to lay down the keels for eight new battleships instead of the four that had been previously considered. The naval arms race with Germany was well underway.

On 27 September 1911, Prime Minister Asquith was staying at a house provided by one of his brothers-in-law on the coast of East Lothian in Scotland, ‘a restful place, with an avenue of lime trees, an exceptional library, and a private golf course stretching down to the sea.’14 His house guest was the Home Secretary, 36-year-old Winston Churchill. That afternoon they played golf. The Prime Minister’s daughter, Violet Asquith, recalled an encounter with Winston following their game: ‘I was just finishing tea when they came in. Looking up, I saw in Winston’s face a radiance like the sun.’ She asked whether he would like tea. He looked at her ‘with grave but shining eyes. “No, I don’t want tea. I don’t want anything, anything in the world. Your father has just offered me the Admiralty.”’15

Churchill did not believe that a war with Germany was inevitable, but he did believe that British naval supremacy was essential. In February 1912 in Glasgow Churchill gave a major address that provoked both the Germans and the pacifist wing of the Liberal Party.

The British Navy is to us a necessity and … the German Navy is to them more in the nature of a luxury. Our naval power involves British existence. It is existence to us; it is expansion to them. We cannot menace the peace of a single continental hamlet, no matter how great and supreme our Navy may become. But, on the other hand, the whole fortunes of our race and Empire, the whole treasure accumulated during so many centuries of sacrifice and achievement would perish and be swept utterly away if our naval supremacy were to be impaired. It is the British Navy which makes Great Britain a great power. But Germany was a great power, respected and honoured all over the world, before she had a single ship.16

At the stroke of midnight on 4 August 1914, Great Britain declared war on Germany when Britain’s ultimatum demanding that Germany withdraw her Army from Belgium expired. John Catterall Leach was 27 days from his twentieth birthday. He was no longer a midshipman. He now wore the stripe of a sub-lieutenant of the Royal Navy. In less than two years he was promoted to Lieutenant. His most important sea duty during the First World War was in the battleship HMS Erin. Erin was a new battleship with a curious past; she had been built by the British shipbuilder Vickers for the Turkish Navy. Her ordnance was formidable. She mounted ten 13.5-inch guns in five turrets and sixteen 6-inch guns in individual barbettes. She was also armed with four submerged torpedo tubes. With a length of 559 feet 9 inches, a beam of 91 feet 7 inches and a standard displacement of 22,780 tons she was smaller than the Queen Elizabeth class of British battleships, which were the best the Royal Navy had in 1914. Churchill, as First Lord of the Admiralty, summarily requisitioned Erin as she was nearing completion. The Turkish government considered his action manifestly illegal. Churchill’s action proved prescient as Turkey soon entered the war on Germany’s side.

Lieutenant Leach’s first experience with a fleet engagement came on 29 May 1916 at the Battle of Jutland, known in Germany as the Battle of the Skagerrak. It was the largest naval battle in history and involved virtually every battleship and battle cruiser in both navies. The greater part of the British Fleet was at Scapa Flow under the command of Admiral Sir John Jellicoe. The lesser part consisting of six battle cruisers and one squadron of four fast and powerful Queen Elizabeth class battleships was at Rosyth under the command of Vice Admiral Sir David Beatty.

Winston Churchill as First Lord of the Admiralty. (Courtesy of Imperial War Museum)

HMS Erin was part of Admiral Jellicoe’s main battle fleet of 28 battleships. In the initial encounter the impetuous Beatty led his battle cruisers in a cavalry-like charge at the five battle cruisers of Admiral Hipper’s Scouting Group One. It proved disastrous for the Royal Navy. Two of Beatty’s lightly armoured cruisers were blown up while Hipper lost none. Belatedly, Beatty ordered a withdrawal to the north in order to lure the entire German Fleet into an engagement with Jellicoe’s vastly superior force. At 18.01 on 31 May HMS Lion, Beatty’s flagship, came within sight of Jellicoe who signalled, ‘Where is the enemy’s battle fleet?’17 The answer was ambiguous, but it was clear to Jellicoe that action was imminent and he ordered his six columns of battleships into line. The German vessels soon came within sight. By the classic tactic of crossing the ‘T’ of the German line the British battleships were able to fire broadsides into the German ships which could only reply with their forward turrets.

Erin, which was positioned toward the end of the line of Jellicoe’s battleships, was never able to bring her main armament to bear on the enemy. The Captain of Erin, the Honourable V.A. Stanley MVO, had been the commanding officer of Britannia Royal Naval College. On the first day of the war, it was he who had received the famous Admiralty telegram that simply said, ‘Mobilise’.

Three and a half months after the Battle of Jutland Lieutenant Leach was mentioned in dispatches. A supplement to the London Gazette, no 29751, published by authority of the Admiralty on 15 September 1916 read, ‘Performed very good service as officer in charge of a turret.’18 The same issue announced that the seniority of Acting Lieutenant John Catterall Leach is to be antedated to 30 June 1916. Both before and after the Battle of Jutland Captain Stanley gave Leach exemplary fitness reports. On 16 May he wrote, ‘Cannot speak too highly of him. His work is always of a high standard.’19 Then on 17 June he wrote, ‘Very reliable and thoroughly trustworthy; of marked ability.’20

In numerical terms the Battle of Jutland was a German victory as the British suffered far greater losses than they inflicted. The battle cruisers Indefatigable, Invincible and Queen Mary had been sunk as were three armoured cruisers and eight destroyers. A total of 6,097 British sailors perished. The Germans had lost the battle cruiser Lützow, a pre-Dreadnought battleship, four light cruisers and five torpedo boats; 2,551 German sailors died.

While three of the fast British battleships, Warspite, Barham and Malaya had suffered extensive damage requiring dockyard repairs, the main battle fleet, including Erin, was unscathed. The Grand Fleet still outnumbered the German Fleet by 28 Dreadnoughts to 16. The military historian John Keegan noted that

For more than half the war, therefore – from 1 June 1916 until 11 November 1918, 29 months in all – the High Seas Fleet was at best ‘a fleet in being’, and for its last year scarcely even that … the central factor in the reduction of the High Seas Fleet to an inoperative force was the action of Jutland itself.’21

In strategic terms Jutland was undoubtedly a British victory. Jutland dominated British naval thinking for over two decades. For many it confirmed that the battleship was the ‘Queen of Battle’. For many it established that, for the indefinite future, the fleet having the largest number of battleships with the heaviest guns and the thickest armour would always prevail. Jutland emphasised the importance of the gunnery officer. Afterwards the best and brightest young officers in the Royal Navy gravitated toward gunnery. Lieutenant J.C. Leach was already a gunnery officer but Jutland may have influenced his decision to make gunnery his speciality for the rest of his career.

That summer Leach had more than just Jutland on his mind. He had fallen in love with Miss Evelyn Burrell Lee of Bovey Tracey, Devon. He was determined to win her heart and to gain her father’s approval of their marriage. He succeeded on both counts.