Jackson Pollock was the sort of person that Thomas Hart Benton pretended to be: the child of poor, working-class drifters, with little education and few prospects. In a sense, Pollock was the embodiment of the impoverished, inarticulate America that Benton sought to capture, out of some strange, seemingly illogical conviction that something about these people was beautiful.

Thomas Hart Benton liked to present himself as a crude, uneducated hillbilly, but in fact he was very far from that. He was the son of a U.S. congressman, spent much of his childhood in Washington, D.C., went to private schools, and was exposed as a child to art, classical music, fine dining, political discussion, the niceties of social etiquette, and books of all kinds, particularly works on politics and history. To be sure, as a boy Benton also spent time in Neosho, Missouri, where he was exposed to the hardscrabble life of Ozark farmers. During his years of struggle to establish himself as an artist, he experienced poverty that was very real, supporting himself through hard manual labor, such as working as a stevedore, and even stealing food to survive. But Benton’s inner self-confidence despite years of devastating rejections, his wide range of interests, and his remarkable skill with words, which made his autobiography one of the best books written in the 1930s, all provide clues that his background was in some way socially privileged; these things reveal, despite all his pretenses to the contrary, that in actual fact he came from a family of prominent lawyers and politicians rather than people who were simply laborers or subsistence farmers. As the folksinger Burl Ives commented in an interview with Ken Burns: “You see, Tom Benton . . . He liked to be a ‘hail fellow well met’ and one of the gang but he wasn’t. He was an introspective, thinking man. He was very well read—all the classics—but he didn’t want anybody to know it. Tom Benton was an aristocrat.”

The bond between Benton and Pollock, in short, was far from straightforward; it was forged out of their differences as well as their emotional connections. Indeed, even when we retrace the jagged history of their relationship, there are several key events that seem highly implausible: Pollock’s decision to become an artist (a profession hardly typical for someone of working-class background); his learning about Benton and seeking him out as a mentor; their forming a lifelong bond (which was broken only by Pollock’s death); or Pollock’s ascent to his position as the most celebrated figure in the history of American art.

Both of Jackson Pollock’s parents, Stella and Roy, came from brutally humble backgrounds, similar to that of the Ozark hillbillies, the people often described as “white trash,” whom Benton liked to sketch. Pollock’s mother, Stella McClure, the eldest child in her family, was born on May 20, 1875, in a log house near the little town of Mount Ayr, Iowa. Her parents were stern Presbyterians who believed that there was just one straight and narrow path to salvation. Life on the McClure farm was harsh and strictly regulated, and misfortunes, which came frequently, were accepted with a kind of stoic resignation. One of Stella’s sisters died of convulsions in her arms; another died young of tuberculosis. Around 1890 the farm failed, and the family moved to Tingley, Iowa, where her father, John McClure, found work as a brick-mason and plasterer.

The woman who emerged from this harsh background was at once strong-willed and strangely inexpressive. “You couldn’t read her at all,” noted Ethel Baziotes, the wife of the painter William Baziotes, when she met Stella in the early 1940s. “She was like an American Indian woman. She sat like statuary the entire evening and didn’t move once, but she followed everything.” Despite her reserve, Stella had a will of iron. “Mother always had control,” Jackson’s brother Charles noted. “She knew what she wanted, and what she thought was worthwhile, and she knew how to get it.”

The background of Jackson Pollock’s father was, if possible, even grimmer than that of his mother. Two years younger than his wife, Roy Pollock was born to the name of LeRoy McCoy on February 25, 1877, on a small farm in Ringgold County, Iowa. In 1879, when LeRoy was two, his mother and sister both died of tuberculosis. Despairing and destitute, John McCoy gave away his infant son to James and Lizzie Pol-lock, a poor farm couple in Tingley who were not his relatives. McCoy then moved back to his home state of Missouri, and not long afterward he married a relatively wealthy landed woman and raised a family. But he never sent for or in any way acknowledged the existence of his first son.

The Pollocks were penny-pinching skinflints and religious zealots. LeRoy grew up in a loveless home and was financially exploited by his foster parents, who often sent him out to work for other farmers and pocketed the modest income. Twice during his childhood, LeRoy ran away from home but returned in a destitute state just short of starvation. Just a few days shy of his twentieth birthday, the Pollocks legally adopted LeRoy, with an indenture that specified that “said Roy McCoy shall hereafter be called Roy Pollock.” Their motive seems to have been to gain legal control so that they could keep him from running away again and continue to financially exploit him. Around the time of his marriage, Roy is said to have attempted to change his last name from that of his hated foster parents back to McCoy, but he didn’t have enough money to pay the fees requested by the lawyer. But for this fact, Jackson Pollock would today be known as Paul Jackson McCoy.

Roy Pollock emerged from this ordeal a shy, sensitive man, no match for the formidable Stella McClure, and he seems to have started drinking to escape his problems while still in high school. Yet in his quiet way, Roy was an independent thinker, opposed to the hypocritical formal religion of his stepparents and a believer in socialism and the rights of working men—“the lone socialist in Ringgold County.”

It’s not recorded how Roy and Stella met, although Roy was a high school classmate of Stella’s younger sister Anna. Their relationship became a romance when they were in their mid-twenties, and in 1902, when she was twenty-seven, Stella discovered that she was pregnant. On Christmas Day that year she gave birth to her first child, Charles, while staying with her sister in Denver. LeRoy Pollock was still in Tingley, but three weeks later he headed west and the two met in Alliance, Nebraska, where they were married with scant ceremony at the Alliance Methodist Episcopal Church by a minister they had met only moments before. With her typical silent stoicism, Stella always concealed the fact that Charles was born out of wedlock. Charles learned the fact only after her death. Shortly after their marriage, the Pollocks moved to Cody, Wyoming, where Roy Pollock worked at a variety of menial jobs. In the nine years they lived there, Roy and Stella had four more sons: Marvin Jay, Frank, Sanford (always known as Sande), and finally Paul Jackson, the youngest, born on January 28, 1912.

Although in his biographical statements Jackson Pollock always mentioned being born in Cody, in fact he had no memories of the place. Ten months after he was born, the family moved to National City, California. After staying there only a few months, they moved to Arizona, and Roy purchased a twenty-acre plot of land six miles east of Phoenix, on the road to Tempe.

The next four years, spanning Jackson’s life from the ages of two to six, were the happiest years for the Pollocks, their only years when they functioned together as a family unit. The house was a small adobe, with just four rooms. There was no bathroom, but rather an out house. During the winter the boys slept in a bedroom with three beds for the five of them, but during the summer they usually slept outdoors, dragging the beds out under the trees. They had a cat and a dog, Gyp, a mixture of collie and terrier, with short legs and a brown patch around one eye. The older children had chores to do, but Jack, the youngest, simply roamed around the place. Jack’s constant companion was his just-older brother Sande, who also cared for him later in life, when they lived together in New York. His brother Frank later recalled that “it was always ‘Jack and Sande’ . . . they were like two burrs on a dog’s tail.” Looking back on these years, Roy would write wistfully: “I wish we were all back in the country on a big ranch with pigs cows horses chickens . . . The happiest time was when you boys were all home on the ranch. We did lots of hard work, but we were healthy and happy.”

This idyll ended in 1917 due to a combination of financial pressures and Stella’s unrealistic dreams. Prices for produce were dropping, and Stella had set her mind on moving on to a place with better prospects and better schools for her boys. On May 22, 1917, they sold the farm at auction. Frank later recalled that his father never got over the disappointment of losing it. As he said, “It was the end of my dad.” At this point the Pollocks began a downward spiral. They would live in seven or eight houses over the next six years while the family gradually fell apart.

In 1917 they moved to Chico, California, where they acquired a fruit farm. The farm lost money, so they moved to Janesville, California, where they acquired a small hotel. The hotel lost money, so they sold it to acquire a farm in Orland, California. But this farm was never actively maintained, since by this time Roy had moved out and was working at odd jobs elsewhere—sending checks home to his wife. The financial situation continued to grow worse. In 1923 Stella sold the Orland farm in exchange for a Studebaker and some cash. She drove to Phoenix, not far from where Roy was then working, and rented a house in a poor neighborhood. When she could no longer pay the rent, she took a job as a housekeeper for a widowed farmer, Jacob Minsch. When Minsch remarried she moved once again, taking a job as a cook on a ranch outside of Phoenix.

Throughout this period Roy drifted from one low-paid job to another in a slow but steady descent, moving from small-scale truck farmer to laborer on ranches and road crews, often half a continent away from his family—slowly drifting away from his wife and five children into despair and alcoholism. For a time the eldest brother, Charles, served as a sort of surrogate father. In 1921, however, Charles quit high school and left for Los Angeles, once again depriving Jackson of a paternal figure. “I sometimes feel my life has been a failure,” Roy wrote to Jackson in 1927, when Jackson was fifteen, “but in this life we can’t undo the things that are past we can only endeavor to do the best possible now.”

After Charles’s departure the family grew increasingly scattered. Jackson, being the youngest, generally stayed with his mother,

while the others drifted in and out of the household, as they struggled to support themselves and find a path in life. In

September 1924 Stella moved again, this time to Riverside, California, apparently so that the two youngest boys, Sande and

Jackson, the only ones remaining under her wing, could attend a good school. Jackson enrolled in Riverside High, but in the

spring, shortly after getting in a fight with an ROTC instructor, he dropped out. Shortly afterward, in September 1928, Stella

moved still one more time, to Los Angeles. She had apparently grasped that Jackson did not connect well with reading, writing,

and academic subjects and wanted him to attend a school that better suited his interests: Manual Arts, a large public school

with over three thousand students, devoted, as its name suggests, to art and vocational training.

The Phrenocosmian Club

Up to this point, Jackson’s life was just a narrative of wanderings. What is remarkable, in fact, coming from the background he did, just one step up from the homeless Okies Steinbeck celebrated in The Grapes of Wrath, is that Jackson Pollock ever chose to become an artist. But his father, Roy, despite his feckless ways, had a love of books and a belief in education as something that could improve one’s life. Above all, Jackson’s mother, Stella, the backbone of the family, had social and cultural aspirations, apparently largely gleaned from reading women’s magazines. She taught her boys to dress stylishly and be well behaved: she had high aspirations for them. She wanted them to rise above the rough, barely subsisting lifestyle that she and her husband had known.

It was Jackson’s brother Charles who turned the family toward art. From childhood Charles had excelled in calligraphy and drawing—an interest encouraged both by his mother and by a series of supportive art teachers—and by high school he had decided that art would provide an escape from the hardscrabble working-class existence of his parents. Remarkably, all five of the Pollock brothers at some point aspired to become artists, and three of them attained this goal. All agree that Jackson chose to become an artist because Charles provided a model for him to do so. As Stella told an interviewer from the Des Moines Register in 1957: “When Jackson was a little boy and was asked what he wanted to be when he grew up, he’d always say, ‘I want to be an artist like my brother Charles.’ ” For years, however, it was Charles who seemed the most gifted member of the family, and Jackson, lacking in any evidence of ability, simply played catch-up.

By the time he settled in Riverside, Jackson had taken on the persona of an artist, although by all accounts he showed no artistic talent and did not do much in the way of actually making art. At Manual Arts he immediately became part of the group that gathered around the most eccentric member of the faculty, the head of the art department, Frederick John de St. Vrain Schwankovsky, generally known as Schwanny. Schwanny had studied at the Art Students League in New York and had then moved to Hollywood to design sets for Metro Pictures. When Metro was absorbed into Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, he was laid off and took a temporary job as a high school art teacher. The temporary job became permanent. Schwanny stayed on at Manual Arts for another thirty-two years, designing stage sets, organizing a fencing team, instituting a “color week,” and singing solos at school assemblies. His own work consisted of amateurish Cézanne-like landscapes, thoroughly conventional still-life paintings, and movie star portraits. But he had been introduced to mysticism by his wife, Nellie Mae Goucher, and he encouraged his students to let their minds go, to paint their dreams, and to “expand their consciousness.” He even formed a philosophical society called the Phrenocosmian Club.

In the period when Jackson attended the school, Schwanny had a cluster of gifted students, several of whom went on to notable careers. The best known of these today is Phillip Goldstein, who later, to hide his Jewish background, changed his name to Philip Guston and became illustrious, like Pollock, as an Abstract Expressionist. Jackson’s closest friend was Manuel Tolegian, who would also go on to study with Thomas Hart Benton and exhibited talent as a painter, musician, and inventor but never hit the big time. Later in life, Tolegian bitterly resented Pollock’s success and disparaged his talent. “He worked hard to make conventional drawings,” Tolegian stated, “but he just didn’t have what it takes.”

Like many other high schools, Manual Arts was largely focused on sports and largely ruled by the football team. Pollock was part of a small artistic clique that opposed this group. In March of 1929 Phillip Goldstein and others printed up a pompously written one-page leaflet opposing the way that sports dominated the school—“we oppose most heartily the unreasonable elevation of athletic ability,” it stated—and even suggesting that letters should be awarded for artistic rather than physical prowess. While he had nothing to do with creating it, Pollock was caught by a janitor distributing the leaflet and was suspended from the school. His co-conspirators Don Brown and Manuel Tolegian managed to graduate, but Phillip Goldstein was identified as one of the authors of the pernicious tract and was also suspended.

As Charles Pollock once commented, his youngest brother always showed a weakness for joining cults, whether they were spiritual or artistic. During the period of his suspension, Jackson attended a spiritual rally presided over by the Indian mystic Krishnamurti. By the time he returned to school in September, he had begun dressing like Krishnamurti and was writing letters about spiritual doctrine to Charles. Unfortunately, spiritual enlightenment did not make his school experience any easier. On the contrary, his long locks and artsy friends made him a natural target. That fall a group of football players attacked him, cut his long hair, and then dragged him to a bathroom, where they forced his head into the toilet. Shortly afterward, Jackson had a fight with the football coach, Sid Foster, and was suspended once again. In February 1930, apparently through Schwanny’s intervention, Jackson was permitted to return on a limited basis, to take classes in modeling and sculpture, but his work was ungraded, and at the end of the term he did not have enough credits to graduate.

That summer, Jackson worked for a time with his father on a road camp, but apparently something about the experience went

bad: according to one account, the two got involved in a fistfight. Jackson returned home from the camp a month early and

never worked with his father again. Indeed, they hardly saw each other again: one might almost say that Jackson’s relationship

with his father ended at this point. But at this seemingly unpropitious time, Jackson Pollock made one of the turning-point

decisions of his life. Rather than returning to school, he decided to go to New York with his brothers Charles and Frank to

study with Thomas Hart Benton.

Benton and the Pollock Boys

Charles Pollock, ten years older than Jackson, was the one who discovered Benton and first went to study with him. In 1926 Charles got a job at the Los Angeles Times and worked his way into the layout department, where the pay was good. He also took art classes at the Otis Institute but was bored by them. One day he picked up a copy of Shadowland, a movie magazine. Very likely he acquired it for the girlie pictures, which were plentiful, but it also carried stories about contemporary art, and it had an article by a young writer named Thomas Craven about Thomas Hart Benton. Charles liked the racy prose with which the story was written. Equally significant, he liked the masculinity and modernity of the work itself, which strikingly contrasted with the insipid California Tonalism and Impressionism that surrounded him. On the recommendation of a friend, the art critic Arthur Millier, he decided to move to New York to study with Benton at the Art Students League.

When Charles knocked on Benton’s door, he was welcomed as if he were the prodigal son. No doubt based on some insecurity in his own character, Benton had a particular affinity with raw young western boys who came east to confront the challenge of making great art. Showing up unannounced at Benton’s apartment on Hudson Street, near Abingdon Square, Charles was “received with open arms,” and from that moment he became not only a regular in Benton’s class but a constant visitor to his home, a virtual family member. By the fall of 1927 Charles had an apartment in the same building as the Bentons, and in the summer of 1928 he visited with the Bentons at their cottage on Martha’s Vineyard. When Charles needed money, Rita found him work designing motion picture display cards for a Long Island printing firm, and Benton found him a part-time teaching job at the City and Country School on West Thirteenth Street, where their son, T. P., was a student, run by their close friend Caroline Pratt. As Charles later confessed, he responded to Benton with “total devotion”: “What ever talent I had when I came to New York was nonexistent. I had only enthusiasm, excitement, and a burning desire to study with him.” He even took to dressing like Benton, quickly shifting from white spats and silk vests to rumpled shirts and suspenders such as Benton wore.

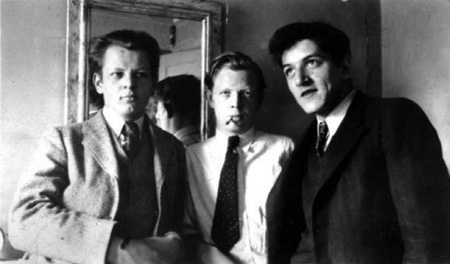

Jackson Pollock (left) with his brother Charles (center) and their friend Manuel Tolegian, shortly after Jackson’s arrival

in New York. (Pollock-Krasner Study Center, Jeffrey Potter Collection.)

Charles was soon followed by his brother Frank, who also came east to study with Benton and also fell under his spell. Jackson, the baby of the family, followed a year later, moving with his brothers into the apartment in the same building as the Bentons. All the Pollocks were treated as if they were members of the Benton family, and they were constantly wandering in and out of the Benton home. Jackson, being the youngest, was particularly mothered by Rita, who would often hire him to baby-sit for T. P. and then use this as an excuse to invite him to stay for dinner. Jackson was quickly pulled into Benton’s artistic orbit as well: within weeks of his arrival, Jackson was doing “action posing” at a loft on Twelfth Street for Benton’s first great mural, America Today.

Even those who didn’t like Benton had to admit that he was an electrifying figure—a kind of lightning rod. As Pollock’s biographers Steven Naifeh and Gregory White Smith have commented:

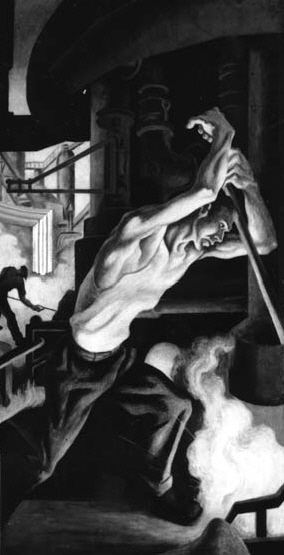

Soon after arriving in New York, Pollock did action posing for Benton’s mural America

Today. (AXA Equitable Life Insurance, Seventh Avenue, New York, Licensed by VAGA, New York)

What Hemingway was to a generation of writers, Benton was to a generation of American painters, the ideal against which, consciously

or unconsciously, they measured themselves—as drinkers, as fighters, as rebels, as provocateurs, as womanizers, as debunkers,

as outsiders, as Americans, and as artists. No one felt the force of Benton’s oversized personality more fully or was more

transfixed by it than Jackson Pollock.

Jackson duplicated his brother’s extravagant admiration for Thomas Hart Benton but did so with even greater intensity. In fact, Benton, then forty-one years old, made a natural father figure for him: he even looked somewhat like Roy Pollock—short in stature, self-conscious, pugnacious, with a creased face and leathery hands. Harry Holtzman commented that Jackson “tailed after Benton like a puppy dog. What ever Benton did he wanted to do.” As George McNeil said, “There was a rhythm between Jackson and Benton from the time they met until the time Jackson died. The rhythm was physical, gestural. The two men were bonded, you could almost say.” Stanley William Hayter recalled that Jackson “never mentioned his own father” but “had found a substitute one in Benton.”

From the first, Benton attracted and was attracted to students of a particular type. Benton was the first American artist

to explore the social problems of America as a whole: to depict rich and poor, worker and capitalist, as well as the full

(or nearly full) range of American regions and professions—north, south, east, and west as well as farmer, coal miner, steelworker,

cowboy, soda jerk, stevedore, tailor, musician, secretary, and stockbroker. Despite his privileged childhood, he looked at

America from the standpoint of the poor and dispossessed; he himself had felt poverty so long and so deeply that this viewpoint

fit him naturally. As a consequence, Benton’s art had a particularly strong appeal to those from humble backgrounds. As Benton

later wrote of Jack:

He was very young, about eighteen years old. He had no money, and, it first appeared, little talent, but his personality was such that it elicited immediate sympathy. As I was given to treating my students like friends, inviting them home to dinner and parties and otherwise putting them on a basis of equality, it was not long before Jack’s appealing nature made him a sort of family intimate. Rita, my wife, took to him immediately, as did our son T. P., then just coming out of babyhood. Jack became the boy’s idol and through that our chief baby-sitter. He was too proud to take money, so Rita paid him for his guardianship sessions by feeding him. He became our most frequent dinner guest.

Although . . . Jack’s talents seemed of a most minimal order, I sensed he was some kind of artist. I had learned anyhow that

great talents were not the most essential requirements for artistic success. I had seen too many gifted people drop away from

the pursuit of art because they lacked the necessary inner drive to keep at it when the going was hard. Jack’s apparent talent

deficiencies did not thus seem important. All that was important, as I saw it, was an intense interest, and that he had.

Figures like Fairfield Porter, who had inherited culture and wealth and had gone to Harvard, could grudgingly admire aspects of Benton and admit that he was a man of sharp intelligence, but they could not quite empathize with Benton as a whole, or embrace his rough-hewn persona. “He had what James Truslow Adams calls the ‘mocker’ pose,” Porter once commented of Benton. “He liked to pretend; he liked to act as though he were the completely uneducated grandson of a crooked politician. I found that sort of tiresome.”

To those of more humble origin, however, particularly those who, like Pollock, came from the West, he was a friend, a model, a magnet, an inspiration. Indeed, westerners, such as the Pollock brothers, were always at the center of Benton’s circle. For some reason, regardless of their level of artistic talent, he felt a particular fondness for them: probably they reminded him of the country boys who had been his companions during his childhood in southwest Missouri. In fact, Jackson Pollock was the paradigm of the kind of student Benton liked best: a westerner from a poor background, preferably rural, who had an emotionally troubled relationship with his father. In complex ways these traits all mirrored qualities of Benton himself.

Since they were generally poor, most of Benton’s students had trouble paying tuition. Benton always had to scramble to get them scholarships or find them odd jobs sweeping floors or working in the cafeteria of the League. Edith Bozyan, who also studied with Benton at this time, has told me that Rita Benton arranged for milk to be delivered to the Pollock brothers every morning at her own expense and that this provided their only breakfast since they didn’t have enough money to buy food. Indeed, Rita mothered all of Benton’s students and looked for suitable excuses to invite them to her spaghetti dinners. When Jackson was sick, Rita nursed him.

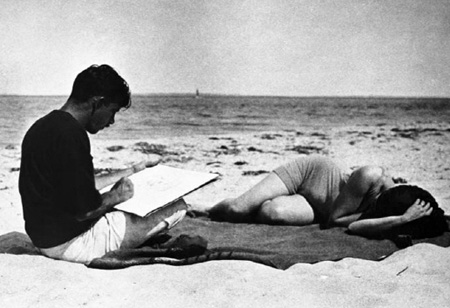

Top: Thomas Hart Benton sketching his wife, Rita, on the beach at Martha’s Vineyard, 1922. Bottom: Jackson Pollock (far right) with Rita (left), Benton’s son, T.P. (with the dog), and a group of friends. (Benton research

collection, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City.)

Rita Benton

While Tom was short and swarthy, Rita Benton was tall, slender, and exceptionally beautiful in a dark-toned Italian way that must have seemed thoroughly exotic, almost otherworldly at the time. The beauty was not simply in her figure but in the way she moved, and laughed, and greeted people. “Oh boy, Rita Benton! Boy . . . what a woman,” commented Benton’s student Earl Bennett, when Ken Burns asked about her. “There was more fire in that Italian lady than I ever saw in any woman. I loved Rita, and I think anybody who knew Rita loved Rita Benton.”

During his early years in New York, Benton’s inability to retain girlfriends had provided a subject for mirth among his friends. One of them became so angry that she stabbed him in the back with a kitchen knife. None of them seemed to last for very long. Then to everyone’s amazement he finally found a woman who would put up with him. Their one point of mutual agreement was that the other was fundamentally unreasonable. “No American woman would put up with Tom,” Rita declared repeatedly, while Benton once took aside Rita’s brother Santo to explain to him, “It’s been very hard to live with your sister all these years—a hard woman to get along with.”

Rita’s relationship with Tom was high drama at every moment. Instead of the long silences, the unspoken resentments and tensions, of the Pollock household, the Benton home was one of constant verbal skirmishes. “They were always hollerin’ at each other,” recalled one of the neighborhood children, Margo Henderson, “and he used words that made a child’s hair curl.” But for all his bluster, Benton put everything practical in his wife’s hands. Benton’s friend Roger Baldwin, the founder of the American Civil Liberties Union, has commented that “Tom was Rita’s man, totally dependent, but acted as if he were not.” Despite the macho posturing, it was Rita who took care of Tom completely. She cooked his meals, bought his clothing, cut his hair, read his mail, and sold his paintings. In the early years, she earned money for the rent by designing and fabricating hats and posing for fashion periodicals. Late in life, Benton confided to Santo that he never would have succeeded without Rita’s support. “I was a bum, I would still be a bum, and I wouldn’t have a dime to my name,” he said.

Rita Benton, circa 1920. (Benton research collection, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City.)

She and Benton had met when Benton was teaching at the Henry Street Settlement, when she was about seventeen. Her Italian childhood had been one of utter poverty in a tiny house with just two rooms, one of them the bedroom where the entire family slept in a single bed. But in America her father, Ettore Piacenza, a copper worker, had found a good job, and they had a six-room house in the Bronx, not too far from the subway, complete with a vegetable garden and a henhouse with twenty-six chickens. Since she had arrived in America at the age of thirteen, she never lost her Italian accent, which sounded all the more peculiar because she learned to speak English from a man with a Scottish brogue, and the rhythms of the two languages collided with each other to create a lilt that was utterly unique, voiced in a rich contralto. For Benton she provided a mode of access into the world of Italian old masters, and in one of his most graceful early paintings he portrayed her as a Madonna, with T. P. on her lap.

Initially, Tom was the one who pursued her. One day he asked her to stay after class and made a sketch. When she came back a few days later, she found that he had sculpted her head in plaster, focusing on her swanlike neck, like that of a figure in a painting by Pontormo, which emerged from the base with a curve like that of a breaking wave. As the relationship developed, however, Tom’s ardor seemed to cool and it became she who kept after him, since his memories of the marital conflicts of his parents, combined with his incurable restlessness, made him reluctant to settle down. Eventually she persuaded him to tie the knot: the ceremony took place at St. Francis Xavier Catholic Church in New York, even though Tom was not a Catholic. Neither family was in any way pleased. Tom’s mother was a snob and for the remainder of her life was hardly willing to recognize Rita’s existence. Rita’s family were appalled that she was marrying someone who didn’t have a dime, showed no promise of ever learning to earn one, and was content to live off the income that Rita earned designing hats. “You know, the Italians have a funny way about that,” her brother Santo later explained. “They expect the man to support the wife, not the wife to support the husband.”

Rita never seems to have been distressed by their poverty, which was such that when their son was born they had no money to buy a cradle and kept him in a bureau drawer. At a low point early in their marriage, they were living in a five-story walk-up with just two rooms, with no light except for a kerosene lamp and no heat other than the kitchen stove. Their furniture consisted of a table and two chairs. One day Thomas Craven’s wife, Aileen, came by for a visit and was appalled by their abject poverty. “How can you live under these conditions?” she exclaimed. To which Rita replied, with a touch of hauteur, “My husband is a genius.”

Yet while devoted to Benton, Rita greatly enjoyed the attention of other men as well. Ruth Emerson has commented that “she was often flirtatious with other men . . . even with my husband, and he was crazy about her.” Pollock’s friend Reuben Kadish recalled that “she was a very flirtatious woman, very vivacious, very Mediterranean. She had a way of making you feel, as you sat at a table with twenty other people, that she had cooked this meal especially for you.” Jackson’s brother Frank has confessed that the seductiveness of her beauty was sometimes overwhelming: “She had winning ways that were pretty damned hard to resist. Her lips were different than Mother’s. She had an angular face and polished skin, black hair and sparkling eyes—a voluptuous Italian, very voluptuous. I wasn’t used to being in such company.” Frank once found himself alone with her in the kitchen, and Rita started discussing a book about lesbianism that she had been reading, The Well of Loneliness. “I got very uncomfortable with just the two of us there,” Frank recalled. On another occasion he accompanied Rita and some friends to a Harlem club, where a male stripper named Snake Hips went through a twenty-minute serpent dance. At one point Frank felt Rita’s hand on his knee. “I wasn’t used to that sort of thing, and all I can remember is my embarrassment. I couldn’t believe it was true,” he would say years later.

Among the many who fell in love with her was Jackson Pollock. Indeed, the greater part of his interaction with the Bentons

occurred not with Tom but with Rita. She immediately took to Jackson, who became her special child, and he responded with

complete devotion. In New York he did chores with her, washing windows and sweeping the apartment while she supervised, and

on Martha’s Vineyard he spent most of the day in her company, while Tom disappeared into his studio to work. “She was the

eternal mother,” her niece Marie Piacenza has commented. “Mother with a capital M. She just adored and worshipped children, her children, all children.” “She was the mother of the world,” one neighbor recalled.

Tom Benton as a Teacher

To understand his influence on Pollock, it is helpful to know something of Benton’s background as a teacher. He first became

involved in teaching in 1917 at the Henry Street Settlement, through his friendship with a Jewish art organizer and social

idealist, John Weichsel, the founder of the People’s Art Guild. His main job was to keep an art room open, but he also provided

instruction, to the extent that people asked for it. As Benton later told Paul Cummings:

The first teaching I did in New York was in the public schools of the Chelsea Neighborhood Association at night for adults.

I used to set up stilllifes and let them draw them and paint them if they wanted to. I don’t think anybody painted because

the light wasn’t good enough. But we’d draw. And we talked. Young people would come in there, like my wife came as a young

girl—seventeen or eighteen years old—and other young people. I had some very interesting Jews, Italians. Mostly that’s what

they were.

This early teaching ended in 1918, in the final year of the First World War, when Benton entered the navy. When he returned to New York in 1919 he discovered that the People’s Art Guild had folded, so he did not go back to the Chelsea Neighborhood Association. But most probably it was through his friendship with Weichsel that he briefly taught at the Young Women’s Hebrew Association in 1919.

The next few years, from 1919 to 1925, were the years in which Benton developed his mature artistic style. During this period he did not teach. In 1926, however, he took up teaching in earnest when his friend Boardman Robinson got him a position at the Art Students League. The job paid $103 a month, the first steady income Benton had enjoyed in years. For the next fifteen years—the most productive period of his career—teaching played a major role in Benton’s life. Throughout this period Benton’s social life consisted largely of contact with his students. “If I’d stayed in New York I would have stayed with the League,” Benton told Paul Cummings, about a year before his death. “I’d be there yet. I liked the place. It was very exciting with all those young people all the time.”

The Art Students League, founded in 1875 by a refugee from the conservative National Academy of Design, always catered to free spirits. It had no required courses, no fixed standards of instruction, no grades, and no class attendance records. Students enrolled month-to-month for twelve dollars, a significant sum at the time. Benton taught in Studio 9, on the fifth floor at the top of the stairs. He chose as his focus life drawing, since it allowed him to work from a live model and he couldn’t afford one on his own.

Loosely speaking, one might divide Benton’s teaching into three phases, each one of which attracted a distinct group of followers. During the twenties, when he was still considered a modernist, he gathered around him a small, informal, irreverent, and extremely diverse group. Except for Boardman Robinson, who had gotten him his job, Benton saw nothing of the other teachers at the League. Indeed, he was critical even of Robinson, who he felt was too wrapped up in the “great master” role and too aloof from his pupils. He made a point of treating his students as equals. “My students didn’t study under me but with me,” he once boasted. Several figures in Benton’s circle at this time went on to play a major role in American art, including the painters Reginald Marsh and Fairfield Porter and the sculptors William Zorach, Gaston Lachaise, and Alexander Calder. There were also some good writers, including Lewis Mumford, the Marxist historian Leo Huberman, the poet e. e. cummings, and Benton’s former roommate, the vituperative art critic Thomas Craven, who at this point had aligned himself with progressive trends and was blasting away at academic painters for the modernist magazine The Dial.

“I began with very few and I never had a big class,” Benton later recalled. (When Charles Shaw joined his life drawing class in 1926, it contained only six students.) “But I had some very interesting people,” Benton added. “I would say an awful lot of artists who became well known were my students there. If they weren’t students they were visitors to the place, say, like Sandy Calder and Reggie Marsh.”

“We had a crowd,” Benton told Paul Cummings. “They’d come down to my house. We had dinners and parties.” Stewart Klonis, who studied at the League in the twenties, later commented of Benton that he “was very pugnacious, very independent. Yet his students were terribly devoted to him . . . There was a great deal of camaraderie among the students. It was a very close group.”

With a few loyal exceptions, such as Charles Pollock and Thomas Craven, this early circle began to dissolve around 1930, when Benton completed his mural America Today and his reputation soared. This marked the beginning of a second phase. No doubt jealousy was part of the problem. Some members of the group, such as Lewis Mumford, became estranged; others just drifted away. But the Benton home remained a sociable place, with an endless assortment of interesting guests, from the perennial Socialist candidate for president Norman Thomas to the French experimental composer Edgar Varèse.

Of particular interest to Pollock was the Mexican painter José Clemente Orozco, whose great mural of Prometheus he had admired at Pomona College shortly before leaving for New York. Along with David Siqueiros and Diego Rivera, Orozco had achieved world fame in the 1920s as one of the three great masters of the Mexican mural movement. But his scenes of massacres and corrupt officials and priests also earned him enemies, and in 1927 hostile forces became so powerful and threatening that Orozco fled from Mexico and moved to New York. Just as his money was running out, a small group of enthusiasts learned that he had settled in the city and took steps to promote his work. The most eloquent, active, and effective of these supporters was Benton, who arranged Orozco’s first American show in Philadelphia and shortly afterward organized an ambitious retrospective at the Art Students League—despite violent resistance from other members of the League who objected that Orozco was not on the faculty and, in addition, was a Mexican and foreigner rather than a true American. With characteristic forcefulness, Benton rode roughshod over the opposition. The show he organized brought Orozco both publicity and much-needed sales, and from that time forward Orozco always remained friendly and loyal to Benton, even during difficult dips in his career. For a time Benton even showed at the Delphic Studios gallery, managed by Alma Reed, Orozco’s blond and buxom mistress.

While the early thirties saw many departures from Benton’s circle, the empty spaces were quickly filled by young students, such as the Pol-lock brothers, who often came from some distance to study with Benton, generally because they were attracted to the social content of his work. These acolytes fit into three fairly definite categories: poor city boys, mostly Jewish; poor blacks from the Deep South, who had somehow gotten the money to come north to study (for a time Benton attracted nearly all the African Americans at the League); and poor working-class boys, generally of rural background, from the West. Axel Horn, who began studying with Benton in 1933, noted that inside his class “was a hard core of devotees who spent much of their time outside the class with Benton, as his assistants and as models for a mural on which he was working, and also playing in the hill-billy band that he had organized.”

Thus, the range of Benton’s acquaintances narrowed to include fewer peers and a younger, less critical group of followers. Despite, or perhaps because of, this change, the atmosphere around Benton grew even more focused and intense. Students tended to cluster around favorite teachers, and Benton was notorious for attracting a group of loyalists, who stood apart from everyone else in the school. They not only studied with Benton but socialized with him and imitated the way he spoke and dressed and his cocky walk.

Jackson Pollock came to study with Benton just at the time this second phase, with its musical emphasis, was beginning. Benton drew him several times, and Pollock appears in two of Benton’s major paintings, The Ballad of the Jealous Lover of Lone Green Valley of 1931 and the panel of Arts of the West in Benton’s 1934 Whitney Museum mural, in both of which he plays the kazoo.

The third phase of Benton’s stay in New York, from about 1932 to 1935, was the most difficult. With the rise of hard-line Marxism, Benton’s irreverent treatment of working-class Americans became politically suspect, and after he executed his mural for the Whitney, with its panoramic survey of American types, he was even accused of racism or anti-Semitism. During this period many of Benton’s Jewish and African American students dropped away, and hecklers began to show up at his lectures. Benton’s enrollment in his class fell from twenty-nine in 1930 to only seven in the fall of 1932. Several longtime friends, such as the historian Leo Huberman, broke off all contact with him. “Damn it!” Benton told Paul Cummings. “There were a lot of those who were my students who became my enemies when the thirties came . . . But I just can’t remember their names. They were important for a moment but they never really made any impact.”

Throughout this difficult period a strong core of supporters, such as the Pollock brothers, and a number of old Jewish friends, such as his personal lawyer, Hymie Cohen, remained loyal. But due to the pressure of work and the irritation of public harassment, Benton drank heavily and began showing up at his classes only infrequently, sometimes drunk, often being gone for months at a time. This period of emotional tension finally came to an end in 1935, when Benton packed his bags and moved back to his home state of Missouri.

To replace the writers and intellectuals who deserted him in the early 1930s, at this time Benton began to socialize with composers and musicians. He himself had just become involved with music, since he had taken up the harmonica to amuse himself while in an emotional slump after completing his New School mural. Before long he pulled his students into his new interest. Charles Pollock learned to play the harmonica (badly), and Bernard Steffen and Manuel Tolegian grew extremely adept—Tolegian so much so that in 1939 he performed on the harmonica for a show on Broadway, the Pulitzer Prize–winning William Saroyan play The Time of Your Life. Since none of them could read music, Benton devised a new form of musical notation, showing them which hole to blow through and whether to draw in or blow out. “There was plenty of drinking,” Charles Pollock recalled, “and, I suppose, here and there, some serious discussion.” The students were often joined by Benton’s neighbors, including a local furrier who played the guitar.

“I was always looking up suitable music,” Benton told Paul Cummings. “Digging around in the libraries for early forms. Our

orchestra attempted Bach, Purcell, Couperin, Thomas Farmer, Josquin Desprez, and others . . . My ear improving, I picked up

American folk tunes on my summer travels.” Thanks to his new musical interests, Benton made a number of new friends at this

time, including the musicologist Charles Seeger (father of the folksinger Pete Seeger) and the composers Carl Ruggles and

Edgar Varèse. Ruggles even composed some music for Benton, which the harmonica troupe performed at the opening of Benton’s

show at the Ferargil Galleries in 1934.

Becky Tarwater

Pollock’s most intense, if peculiar, early romance related in interesting ways to Benton’s musical interests. In February 1937 Tom and Rita, who by then had moved to Kansas City, came back to New York for the opening of a show at the Municipal Art Galleries including work by many of Benton’s former students and held a party at their former apartment on Eighth Street, then occupied by the Pollock brothers.* While the party celebrated painting, country music was the dominant theme of the affair, and it included a reunion of the Harmonica Rascals, with Bernard Steffen on the dulcimer and Sande Pollock, Manuel Tolegian, and Benton harmonizing on the harmonica. Other musicians came as well, and at the event Jackson fell instantly and passionately in love with a young woman with a pale face and shoulder-length brown hair who sat on a stool in the front room, her back against the window, playing a banjo and singing sad Tennessee ballads in a high, plaintive voice.

During an emotional slump after completing America Today, Benton taught himself to play the harmonica. Here he performs with his wife, Rita, and his son, T.P. (Benton research collection,

Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City.)

This was Becky Tarwater, who, like Benton, was a peculiar mix of hillbilly and sophisticate. Born in Rockwood, Tennessee, she came from a well-to-do family, went to a girls’ school in Philadelphia, studied dance and music for eight years in Washington, D.C., and even spent a year in Paris. But she never lost touch with her Tennessee roots. “We were hillbillies,” she later commented, without shame.

Being a hillbilly meant learning ballads. In her family everybody sang, and she learned eighteenth-century ballads as a child from her grandmother, who in turn had learned them as a child from her mother and grandmother—a lineage of musical transmission that quickly brings one back to colonial times and the very early days of the western frontier. In fact, at the time of Benton’s party, Becky had just come from making a recording of “Barbara Allen,” for the Library of Congress folk music project of Benton’s friend Charles Seeger. Sung without accompaniment, her performance has become something of a classic: one of the purest reflections of a form of music dating back to the eighteenth century and earlier, which had somehow survived unsullied in the isolation of the Tennessee hill country.*

Pollock’s romance was passionate and brief, since it existed only in his own head, and Becky already had a boyfriend, a doctor with the fit-ting name of Hicks, who had been her childhood suitor. When she left the party, Jackson followed her, staying a few steps back and, in a kind of child’s game, stopping when she stopped. On the street he stayed at a distance, and when she turned back to look he would duck into a doorway. At the Astor Place subway station she turned on him and said quietly but firmly: “Jack, I don’t want you coming home with me. I am perfectly all right.” She was staying at a women’s hotel, the Allerton, on Fifty-seventh Street, and didn’t want Jackson to appear there and cause a scandal.

She had left behind her banjo, and Jackson immediately decided that he would become a musician, even asking his friends for an instruction book. But his talents did not lie in this direction. As he noted in a letter to Charles, “All I’m able to do so far is to get it out of tune.” She returned to the apartment a number of times for dinner, and she and Jackson had a relationship for about five months, although not one that she ever took seriously. They never went out on a date or out to dinner at a restaurant, and he never spoke about his past, his family, or his painting—she later commented that “painting and anything of that sort wasn’t on his mind.” She remembered him as “a tortured, sensitive person who was very touching,” but he never touched on the sources of his mental anguish. She felt that what he needed was not a wife but a mother. On one occasion she witnessed his anger. When they were out walking he saw a well-dressed woman with a tiny dog on a leash. Something about her attention to the animal outraged him, and he went over and began kicking the dog, in a shocking, seemingly inexplicable outburst of violence completely at odds with his usual gentle manner. “I was terrified the police would come,” Becky recalled.

They met for the last time at a White Castle restaurant not far from the Eighth Street apartment, just before Becky returned to Tennessee. Jackson walked in carryinga single white gardenia, and after they sat down, surrounded by the aroma of grease and onions, he impulsively asked Becky to marry him. She paused for a moment, not because she took the offer seriously but to reflect on how to reply. She then explained how marriage with him would not fit with her plans for her career and said that if she did marry she would choose her childhood sweetheart, Mason Hicks, who was then finishing a residency at Bellevue Hospital. When she was done, she picked up the gardenia and walked away. Jackson never saw her again, although the next summer he sent her a letter with a painting of tuberoses and asked her to stay in touch with him.

She never did. A few months later she married Mason Hicks and returned to New York, where he developed a successful practice

and the couple lived in a fancy apartment on Fifth Avenue. For the next twenty years she watched with approval when she saw

Jackson’s picture in magazines and newspapers, and she once thought of going to one of his openings but decided against it.

“I had another life and it would have been foolish to go outside it,” she later commented.

“My Drawing Is Rotten”

Despite his ferocious reputation, Benton’s comments to his students were invariably gentle. As one of his students, Charles O’Neill, has written: “Benton was a fine man. I don’t remember his ever humiliating a student, even if preoccupied by painting.” Nonetheless, the atmosphere was strangely intense, as many of his students have testified. “In the studio there was no fooling around,” Jack Barber observed. “It was like going to work.” Bill McKim commented, “You learned to work independently, and that is a very important thing.” “Benton demanded a lot of work,” one of Jackson’s classmates at the League later stated. “His students didn’t spend much time in the lunchroom.”

While Pollock idolized Benton, many reports corroborate that he had difficulty mastering Benton’s artistic techniques. Benton later remembered, “He had great difficulties in getting started with his studies, and, watching other more facile students, must have suffered from a sense of ineptitude.” His brother has confirmed this assessment. As Charles Pollock recalled: “Everything Jack did in his student days was a struggle, a struggle for things to come together the way he wanted them to. I don’t know if it was a question of drawingperse, but it was a question of getting things down on the paper in some organized way that suited him.”

Benton’s students were famous for picking up his scribble-scrabble line quality, which made his cross-hatching look like a head of tangled hair, but “Jackson’s drawings were easily the ‘hairiest,’ ” Axel Horn remembered. “They were painfully indicative of the continuous running battle between [him] and his tools.” Pigment gave Pollock as much difficulty as the pencil. “Jack fought paint and brushes all the way,” recalled Horn. “They fought back, and the canvas was testimony to the struggle. His early paintings were tortuous with painfully disturbed surfaces. In his efforts to win these contests, he would often shift media in mid-painting.” Pollock also had difficulty breaking down his work into logical units. He would fuss endlessly over some detail and then leave blank spots in the more difficult passages, such as hands and faces, which he intended to finish later but never got around to. As Benton told an interviewer in 1959, Pollock “was out of his field . . . His mind was absolutely incapable of drafting logical sequences. He couldn’t be taught anything.”

Pollock’s lack of ability strikingly contrasted with the skills of his high school classmate Manuel Tolegian, who had also

come to study with Benton and who rapidly became quite accomplished. “They would insult each other continuously,” one classmate

recalled. “Jack would call Manuel a Turk, which annoyed him no end. It seemed friendly enough, but they were getting in their

jabs.” Tolegian was also more verbal than Pollock. As Axel Horn recalled: “He was always explaining what he was doing. Always

rationalizing it, always defining it.” By contrast, Pollock had difficulty talking about what he felt. As Benton remembered:

He developed some kind of language block and became almost completely inarticulate. I have sometimes seen him struggle, to

red-faced embarrassment, while trying to formulate ideas boiling up in his disturbed consciousness, ideas he could never get

beyond a “God damn, Tom, you know what I mean!” I rarely did know.

Many of his classmates thought that Pollock was mentally stunted. “Jackson always seemed to be in a daze,” one recalled. Benton, however, remained supportive. “The deep wellsprings of the visual art,” he later commented, “are in fact nearly always beyond verbal expression.”

Sensing Jack’s difficulties, Benton often invited him back to his apartment on Hudson Street, where he provided private instruction in drawing and composition. After class ended at the League, he and Benton would ride the subway together to Fourteenth Street. By early 1931 Frank was at Columbia and Charles was teaching, so Jackson often came alone. Pol-lock seems to have been the only student at the League who enjoyed such easy and intimate access to the Benton home.

It is no exaggeration to say that Benton created Pollock as an artist. The fact is, we have nothing that Pollock made before he worked with Benton, and before working with Benton he seems to have made very little. What we know of Pollock’s work before he studied with Benton is pretty much what he himself confided in a letter to Charles in which he commented: “My drawing I will tell you frankly is rotten it seems to lack freedom and rhythm it is cold and lifeless, it isn’t worth the postage to send it . . . The truth of it is I have never really gotten down to real work and finished a piece I usually get disgusted with it and lose interest . . . Although I feel I will make an artist of some kind I have never proven to myself nor anybody else that I have it in me.”

Such feelings can easily lead to paralysis. Perhaps Benton’s greatest lesson to Pollock was to set aside such worries; he

believed, above all, that artists shouldn’t sit on the couch but should get up and do something. At some level Benton was

naturally a brooder: perhaps in reaction against this, he made his art not a matter of neurotic musings and self-examinations

but of constant action and motion. He himself was in a constant swirl of activity. If a painting didn’t work, he wouldn’t

sulk but turn it over and make a new painting on the back. If that didn’t work, he would turn it over again and make another

painting still. Creative breakthrough, he believed, was not simply a matter of abstract ideas but of new possibilities suggested

by one’s play with materials. As he once wrote:

The creative process is a sort of flowering, unfolding process, where actual ends, not intentions but ends arrived at, cannot

be foreseen. Method involving matter develops, whether the artist wills it or not, a behavior of its own, which has a way

of making exigent demands, devastating to preconceived notions of a goal. Art is born not in preconception or dreaming but

in work. And in work with materials whose behavior in actual use has more to do than preconceived notions with determining

the actual character of ends.

Could there be a better statement of Pollock’s creative approach, in which unforeseen developments, like splatters and drips—the surprises that come about in making things—help to shape the ultimate artistic product?

Art history seeks explanations, but frequently any review of historical facts comes upon critical junctures that are not easy to construe—things that are inherently puzzling, bizarre, and irrational, things that defy any simple form of answer. It’s surely curious that Benton, an exceptionally literate man, did not focus on the seemingly most talented, cultured, and well-connected students in his class—on upper-crust material, on people with education and pedigree, such as Whitney Darrow, who had attended Princeton, or Fairfield Porter, who had studied at Harvard with Ralph Waldo Emerson’s grandson Edward Forbes. How can we explain that Benton attended instead to Jackson Pollock—an uncouth, awkward, inarticulate working-class western boy, who couldn’t paint or draw with the slightest skill, whom many dismissed as mentally a dullard, who in the view of most lacked even the slightest hints of artistic vision or talent? On the face of it Benton’s behavior seemed utterly perverse.

Not surprisingly, many of Benton’s contemporaries were mystified and offended by the way he behaved. They dismissed him as a hillbilly, a boob, a figure with a chip on his shoulder—someone with no real understanding of either art or culture, a figure fundamentally insensitive and anti-artistic. Indeed, this view of Benton is still widely held today. For some reason the nasty name-calling has stuck, and art historians still take pleasure in showering Tom Benton with mud.

Yet in this instance, at least, Benton’s decision seems exactly on the mark and stunningly, almost miraculously clairvoyant.

Could Benton have somehow sensed that Jackson Pollock was destined to become “the greatest American painter”—the figure who

would not only change the face of American art but alter the very fabric of American culture? Perhaps that’s going too far,

given the emotional turmoil of their relationship, but what’s clear is that Pollock would not have become the artist he did

without Benton’s influence—and without his very real, if roughly expressed, affection.

Hollows and Bumps

Benton taught by example rather than through a rigorous set of exercises. He made few criticisms and from the conventional standpoint wasn’t much interested in technique. Once he had provided some initial stimulus, he usually didn’t interfere with what his students were doing unless they asked him to. He left them free to flounder around and find their own way. As Peter Busa recalled, Benton “was less interested in looking at what we were doing than in principles and ideas.” “He seemed to talk more about life than about art,” Herman Cherry recalled. “He’d been through the art-for-art’s sake stuff and wanted to get back down to earth.”

Throughout his career, Benton taught by working alongside his students, and his teaching focused on the problems that he himself

was trying to solve. “I taught what I was trying to learn,” Benton once commented. At the time he began teaching at the League,

for example, he was just beginning to produce large-scale mural compositions, for an epic series on American history, but

was unable to afford a model. Since the League provided one, he was able to spend much of his classroom time making studies

for his paintings. Benton confessed:

Looking back I can see that I was not a very practical teacher, especially for novices . . . Although I had pretty clear ideas

as to my ends, I was still searching for a means to achieve them. Often, when I needed a figure action for some painting I

would use the class model, making mistakes, rubbing out, and destroying my studies, with complete indifference to suspicions

of ineptness that might be aroused among the students. After indicating in a general way the directions I thought profitable

to pursue, I expected the members of my class to make all their own discoveries. I never gave direct criticisms unless they

were asked for and even then only when the asker specified what was occasioning difficulty. There were several more convinced

leaders of the young than I at the Art Students League, and my students were always leaving me for them because, as they said,

“I did not teach anything.”

Figure drawing always remained the core of Benton’s classes at the League. And despite his disclaimers, Benton had a very definite approach to figure drawing and composition. While his methods evolved over time and changed significantly after he moved to Kansas City, he always remained true to certain basic principles: teaching through doing, a distinctive style of figure drawing, and extensive analysis of composition, including analysis of the old masters. As Charles Pollock later noted, “Benton had a perfectly logical system of teaching, and it remained consistent from beginning to end.”

While Benton shared with the École des Beaux-Arts a strong interest in the human figure, his method was exactly opposite to that of the École in two respects. In the first place, he taught a different approach to drawing. The École taught students to achieve a polished surface and a photographic look, even if the underlying structure was a little wobbly. Benton, on the other hand, taught his students to work toward an understanding of the bulges and hollows of the sculptural form, with a network of agitated lines, and to completely eschew any elegance of surface effect. As a consequence of this attitude, the work of all Benton’s students had a distinctive look. Thus, for example, Axel Horn recalled that “in a matter of weeks, drawing on brown wrapping paper with the characteristic scribbly line, I had adopted the class objectives—to be able to articulate and express the softness, the extensions, the recessions, and the projections of the forms which make up the human figure.” Ed Voegele remembers that Benton encouraged him to abandon his search for the perfect line: “He told me to use many lines when sketching, giving the viewer the opportunity to select the line that is most pleasing. This participation permits the viewer to enjoy an experience of creating an image. At least that’s my interpretation of Tom’s theory.”

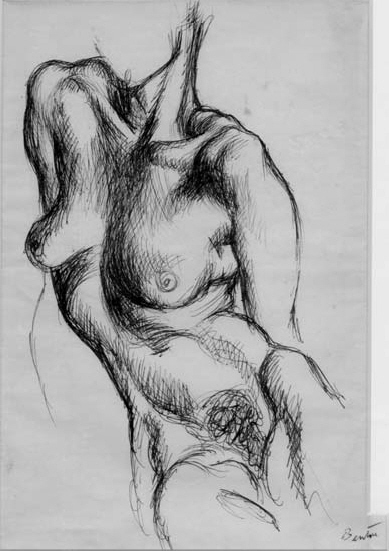

Benton’s key phrase for figure drawing, “the hollow and the bump,” signified a search not only for curvatures but for rhythmic relationships. The phrase had an almost mystical significance, like the yin and yang of Oriental philosophy. Focusing on this principle was a means of discarding conventional ideas of rightness or mechanical precision and focusing instead on a kind of rhythmic flow. Indeed, while some of Benton’s drawings of this period are stunningly accurate, equally fascinating are those in which the proportions are all off, in fact quite grotesque, in which, to cite one striking example, scribbled hastily in pen on a sheet of writing paper, the two breasts are different sizes, the collarbone exaggerated, and the torso oddly stretched, but in which we are nonetheless caught up in the strange rhythmic undulations of collarbone, breast, neck muscles, torso, and thighs, which, taken as a whole, create a wonderful sense of how the parts of the body work against each other, in a moving pattern as tensely harmonious as a beautiful piece of music.

Benton’s figure drawings are often strange in their proportions but wonderfully convey a sense of rhythmic energy. Pollock

learned to draw with a similar disregard of photographic accuracy. (Study of a Female Nude [c. 1916]. Private collection, Cleveland, Ohio.)

Along with making drawings, Benton encouraged his students to look at them; he himself had spent a good deal of time studying the drawings of the old masters, starting with visits to the drawing room of the Louvre when he was a student in Paris. According to Busa he told his students, “When you look at a finished work, you’re just seeing the skin of the building. Look at the drawings.”

In the second place, again in direct opposition to the way he himself had been taught, Benton stressed composition above all

other principles. According to Earl Bennett, Benton would say: “Grand design. You’ve got to get the grand design first. Don’t

get into detail and don’t get into this, that, and the other thing until you’ve got the grand design. When you’ve got the

grand design you can make a painting.” Ed Voegele recalls Benton saying, “If you have a good composition, hang the painting

upside down, down side up, or on either side. The composition will still look good.” Mervin Jules has also left a description

of Benton’s approach:

Every part of the picture had to be broken down into block forms and then reconstructed—everything from a horse’s pelvis to

the turn of an outstretched hand. After that, you would break down the tonality—in other words, where did the light come from?

When you had done that, you would take a piece of transparent paper, put it over the drawing, and using a variety of whites

and blacks, fill in the block figures to indicate the structure of tonal relationships.

In addition to asking his students to create compositions, Benton had them analyze the compositions of artists of the past.

Often the students sketched from projected slides, rendering in abstract the compositions of great artworks from the past,

ranging from Egyptian and Assyrian reliefs to paintings by Rubens and El Greco. As Axel Horn recalled:

His method of analysis was to produce in gray tones a famous work of art, stressing the interplay of direction in the various

forms by simplifying and accentuating changes in plane. Breughel, Michelangelo and Assyrian bas-reliefs were all popular subjects

for this exercise. We would, in addition, construct actual three-dimensional dioramas in wood or clay, treating the painting

as a deep relief, and also painting it in tones of grays, in order to discover for ourselves the rules by which each work

was internally arranged and the forms related spatially . . . Through all this ran the search for the hollow and the bump;

the ability to utilize and express recession, projection, tension, and relaxation.

In carrying out their analysis, Benton taught his students to make two types of drawings. One was to diagram the famous work in lines that explored the pattern of visual movement on the picture surface. The other was to re-create them in cubic blocks, which indicated the spatial position of the principal elements. In short, Benton was interested both in linear flow on the surface and cubist organization in depth. The trick of successful pictorial organization, so he believed, was to coordinate these two systems.

Benton’s emphasis on composition was completely at odds with the Beaux-Arts approach, which taught the student how to render the figure but not how to make a painting. When Thomas Eakins, for example, studied in Paris, he learned to draw from plaster casts and to render the nude model first in pencil and then in oil. But at no point during his years of study, first with Jean-Léon Gérôme and later with Léon Bonnat, was he actually expected to make a painting. He made his first original composition only after he had left his teachers, and at the time he returned to the United States he had only made a single figure painting—an extremely awkward one.

What were the sources of Benton’s teaching approach? Not his own academic training; in fact, his system was consistently at

odds with the methods by which he himself had been taught. Instead, though certainly endowed with some quite personal twists,

Benton’s teachings were derived from his youthful romance with modern art. More specifically, his methods were rooted in his

friendship with Stanton Macdonald-Wright and in his involvement with Synchromism, a movement that synthesized the achievements

of Henri Matisse, Pablo Picasso, and the other leading modernists of the time.

* In September 1933 the Bentons had moved from Hudson Street to an apartment at 10 West Eighth Street. By 1935 they were living in an apartment at 46 West Eighth. The Pol-lock brothers took it over when Benton left New York for Kansas City in the spring of 1935, and it was there that Jackson painted many of his early masterworks, including his mural for Peggy Guggenheim.

* Becky Tarwater’s rendition of “Barbara Allen” is the fourth cut on the CD Anglo-American Ballads, American Folklife Series no. 1, Rounder Records in collaboration with the American Folklife Center, Library of Congress.