Perhaps the most remarkable thing about Synchromism was its sheer audacity. The Synchromists wanted to capture the art world; they wanted to be the leaders of modern painting; they wanted to push outside the usual confines of technique into light shows and other extravaganzas; they wanted to change art history and art criticism. While they made a point of being controversial and rude, they also wanted everyone to love them: and they wanted not simply to be esteemed by the cognoscenti but also to earn popular fame and wealth. While their presumption was almost unbelievable, they did, in fact, accomplish quite a number of their goals. By synthesizing the accomplishments of such figures as Cézanne, Matisse, and Picasso, they introduced a new movement of modern art and created some truly remarkable paintings. As has been indicated, they were the first to exhibit purely abstract paintings in Paris; they startled New York with their radical artistic ideas; they were the first Americans to write an artistic manifesto; they wrote the first history of modern art to trace its formal development; they organized the first major exhibition in the United States of the work of modern American painters; and one of the circle, Willard Wright, achieved considerable financial and popular success, though not in the realm of serious writing but in the openly commercial genre of the popular detective story.

Impressive feats! Yet despite all this, somehow the Synchromists never achieved the grand triumph that they hoped for. The French did not like their work because they were Americans; Americans were puzzled because it looked too French. While they produced some truly remarkable paintings, they never quite secured either popular fame or a solid art historical niche. Today most people, even most art historians, have never heard of them.

Nonetheless, the Synchromists had a student who was taking in what they did and would push it on to a new level: Thomas Hart Benton. To be sure, Benton’s direct involvement with Synchromism was very brief. But it occurred at a particularly exciting moment, when Macdonald-Wright was making his best paintings, organizing the Forum Exhibition, and (with his brother) writing his seminal history of modern art. From the Synchromists Benton learned to think of a painting in terms of visual rhythm, as an organized sequence of forms; he also learned to promote his work through controversial statements and manifestos. For the rest of his life Benton would design like a Synchromist, although he did so with interesting twists. From Benton’s standpoint, Macdonald-Wright’s art fell short in notable ways: it was too esoteric, too highbrow, too European, and too lacking roots in the dirt and grit of American culture. Benton wanted to Americanize modern art and to translate it into terms that an ordinary man could understand—to produce, as he once declared, an art that “was arguable in the language of the streets.” While Macdonald-Wright was content to import French modernism to America, Benton wanted to make art with an American accent.

One might say all this more succinctly in a different way. In 1930 Jackson Pollock lived seventy-five miles away from Stanton

Macdonald-Wright’s home and studio in Pacific Palisades. Yet instead of studying with Wright, he chose to travel with his

two brothers to New York, twenty-seven hundred miles across the country, to study with Thomas Hart Benton. What was it about

Benton that could pull three working-class boys from California to move to New York with the hopes of becoming great painters

under his guidance? How had Benton changed the rules of modern art? What was his appeal to young American men? A few adjectives

are hardly sufficient to answer this question, for what was unique about Benton was the sense that he had suffered and lived

life to the full. Indeed, in the end, his mesmerizing power over Pollock was the product not only of the forcefulness and

inventiveness of his art but of some peculiar affinity between their two personalities, some underlying commonality of energy,

insecurity, desire to display manliness, and grandiose artistic ambition.

Benton Adrift

The period that followed Benton’s return to the United States was one of the most confused of his entire career. For seven months he hung around Neosho, unclear what to do next. Things finally came to a head because of an affair he was having with a local girl, Fay Clark. One day her father came to call on Benton’s father, M. E., to ask about his son’s intentions. M. E. replied that his son had no intentions, had never shown any sign of practical sense, and showed no signs of being able to support a wife. To prevent the situation from going further, Benton’s parents agreed to give him a small sum of money to get started and shipped him off to become a portrait painter in New York.

He arrived in the city in early June of 1912. For the next ten years Benton would live as a near-starving artist in the city, struggling to survive, struggling to find an artistic direction. His progress during these years was so erratic that at times it feels painful even to retrace his steps. Though he was only twenty-three, those who met him at the time sensed that he was in some way damaged or shell-shocked. Thomas Craven later commented of his appearance at this time that “he looked old and sad and I cannot remember that he ever laughed. He was, I felt, the victim of some strange irregularity of development.”

Shortly after his arrival, Benton took a studio at the Lincoln Arcade, a rambling, seedy rabbit warren of studios located on the site where Lincoln Center stands today. There he slept on a cot whose legs were placed in pans of water for protection against the swarms of bedbugs. A daily morning ritual was dumping out the insects that had drowned during the night.

Benton managed to survive during this period largely through his friendship with two more prosperous individuals who took care of him: Ralph Barton and Rex Ingram. Ralph Barton was a little man with a big head, whom Benton met shortly after his arrival in New York. Their friendship was cemented when it turned out that one of Benton’s ancestors, Thomas C. Rector, had killed one of Barton’s ancestors, Joshua Barton, in a duel.* Unlike Benton, who couldn’t adjust to commercial work, Barton immediately began selling drawings to popular magazines such as Puck and McCall’s and achieved instant commercial success. For much of the next decade he allowed Benton to work in his studio and even, when he was traveling to Europe, as he often did for months at a time, to stay in his apartment.

In addition, Benton enjoyed the friendship and support of Rex In-gram, a handsome Irishman with considerable charm and a hint of a brogue. In 1911 Ingram entered Yale to study sculpture under Lee Lawrie, best known today for his Atlas figure, which adorns Rockefeller Center in New York. Since Lawrie had a studio in New York, Ingram rented a studio at the Lincoln Arcade, where he soon met Thomas Hart Benton and befriended him. Though accomplished in sculpture, Ingram soon took his talents in another direction. A classmate at Yale introduced him to Charles Edison, son of the great inventor, who had his own film company. Edison offered Ingram a job, and the sculptor was soon engrossed in acting, scriptwriting, and directing. Though handsome enough to become a star, Ingram soon discovered that his real gifts were shown when he stood behind the camera. With his background in painting and sculpture, Ingram showed a gift for thinking of film as a visual composition. He was at his best in spectaculars, such as Ben-Hur, The Prisoner of Zenda, and Scaramouche. A master of photographic technique, who used specially treated film stock to create rich tonal effects, he also understood the principles of organizing crowd scenes as a visual design, carefully calculating distances, perspectives, and rhythms of movement.

Benton served as Ingram’s set designer during his early period of filmmaking in New York. At the time the movie business was very loosely run, and Benton became friendly with early silent stars such as Rudolph Valentino and Clara Bow, the “It Girl.” The crew would meet in the evening at Luchow’s restaurant to figure out what they were going to do the next day. There they would agree on what scenes they needed, whether a Moorish palace or an Irish castle, and after a bit of research in the library Benton would work up a distemper painting, doing it in black and white since movies were not yet in color. Professional scene painters would then enlarge it to full scale, and it generally looked surprisingly real when placed behind the actors. On one occasion, Benton even tried acting, playing the role of a drunk in a barroom brawl, much to the distress of his father back in Neosho, who worried that his son’s theatrical antics were destroying his own good reputation.

Benton’s closest friend of this period was the poet Thomas Craven, who shared his financial miseries. Like Benton, Craven came from a midwestern background: he had grown up in Kansas on a farm that had once been robbed by Jesse James. Like Benton, he had a varied job history: he had been a newspaper reporter in Denver, a schoolteacher in California, and a night clerk for the Santa Fe Railroad in Las Vegas, and he had sailed before the mast in the West Indies. Later in life he liked to play up the racy side of these experiences. In Las Vegas, for example, he was the friend of roustabouts and prostitutes, and he had lived for a time in Paris, where he scribbled romantic verse and kept a mistress.

Craven arrived in New York to take the city by storm. Shortly after arriving in New York, he sold two poems to the American Mercury, edited by H. L. Mencken, but for the next eight years he was unable to sell a single manuscript. In order to survive, Craven

often spent the winter in Puerto Rico, teaching Latin and English in a private school. Periodically he would reappear in the

city, move in with Benton or next door to him, and take on a role similar to that of a wife. As Benton recalled:

We frequently lived together or in adjoining apartments. He was a good cook. He’d cook and I’d wash the dishes. So we did

that. They used to think we were a couple of homosexuals because we were always together. But it was for the convenience.

I’ve always liked the association of males anyway.

Richard Craven, Thomas’s son, has commented, “I would say my father and Tom were as close, as inseparable, as two men could be with one another.” The bond was not unlike that of two brothers, and in fact Craven would eventually become an art critic and play the same role in boosting Benton’s work that Willard Wright did for his brother, Stanton.

Despite these friendships, Benton’s career floundered until he reconnected with Macdonald-Wright in 1914. Stanton would later declare that Benton had given up painting and that he deserved credit for reviving his career. This seems a bit exaggerated and is out of line with other accounts, but there’s no question that Stanton’s influence at this time played a key role in Benton’s artistic development.

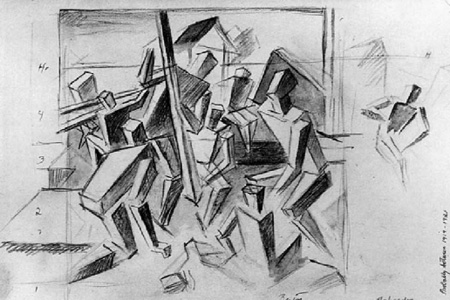

Benton achieved his first notable artistic success two years later, when he was included in the Forum Exhibition through his

friendship with Stanton. Specifically for the show, Benton created a group of paintings in a Synchromist style, including

a large abstraction. The most elaborate of them, now known only from a black-and-white photograph, was based on Michelangelo’s

early relief The Battle of the Lapiths and Centaurs. While the color palette was similar to that of Russell and Macdonald-Wright, the colors were not diaphanous but hard and

firm, as though the figures had been dipped in vats of paint. As Benton told Paul Cummings:

They were spectral. I just simply did Renaissance compositions with spectral color. That’s all it was. But it looked strange

at the time. I did exactly what you see in those drawings of Jack Pollock’s only with bright color . . . I had already done

spectral painting under the influence of Paul Signac. But I never had monkeyed with it in large planes or with the idea of

using it compositionally.

In fact, Benton had come up with something new. While Russell and Wright had explored the muscular tensions and spiral rhythms of Michelangelo, their paintings generally focused on a single figure. On those rare occasions when they tried to go further, their compositions fell apart. Benton had introduced the notion of a multi-figured design, in which the rhythm jumped from one figure to the next. In a fashion that has interesting affinities with Pollock’s later work, the rhythm was not confined to a single section of the design but expanded over the entire composition, running under and over other forms but never leaving the canvas. Ironically, in the end Benton got more publicity than almost anyone else in the exhibition since the art critic for the Herald Tribune, Royal Cortissoz, singled him out for praise. “I didn’t stay with it,” Benton later commented of his foray into Synchromism. “After that exhibition I never did another one. But the influence stayed.”

What stayed was the idea of rhythmic organization—of organizing a composition that led the eye through the entire composition, weaving in and out of deep space. Essentially, Benton had decided to devise a form of Synchromism with less emphasis on color but even more on complex rhythmic sequences of form. And this was the theme he focused on a year later, in March 1917, when he held an exhibition of his work at the Chelsea Neighborhood Association, complete with a little brochure. The paintings were Michelangelesque figure compositions but less brightly colored than those in the Forum Exhibition, with brushwork reminiscent of Cézanne. Notably, the show provided the basis for the first full-scale article on Benton’s work, which Willard Wright contributed to the International Studio. Willard praised the show as “the most important modern exhibition of the month” and singled out Benton’s interest in visual rhythms, declaring that “when an artist at times actually achieves rhythmical line sequences, then a vital aesthetic force has been set in motion.”

One could hardly say that Benton had “arrived,” but he was starting to become a figure worthy of notice, someone to talk about:

granted that much of the talk was hostile, since Benton’s idea of organizing visual rhythms, of basing a design on abstract

principles, grated on the nerves of conventional realists. Around this time, when someone mentioned Benton’s work to Robert

Henri, the leader of the Ashcan School, he responded, “It’s too Michelangelese,” and quickly changed the subject.

Designing with Clay

In the early 1920s Thomas Craven published a novel, Paint, whose artist-hero is closely based on Thomas Hart Benton. In the book, the Benton character dies in 1920. Ironically, it was right around this time that Benton emerged from his decade of floundering and developed a mature and recognizable style—one whose themes were ultimately based on what he had absorbed from the Synchromists but that treated Synchromism merely as a point of departure.

In 1917 and 1918 Benton had made a series of abstract still-life paintings, which were painted from models he made out of paper, wood, and wire. This process seemed to give his compositions a new clarity and intensity. These experiments were interrupted by a brief stint in the navy, where he worked with camouflage and documented the ships and equipment of the naval base at Norfolk, Virginia. But after his release from the navy he went back to his model-making and began to think about how this approach could be applied to the human figure. In the fall of 1919 he came upon an article on Tintoretto that described his procedures for the church of Santa Maria della Salute in Venice. In order to plan his compositions for the church, Tintoretto had created models out of wax and then experimented with their placement and lighting until he found an arrangement that suited him.

As Benton examined Tintoretto’s paintings, with their dramatic sculptural qualities, he became convinced that they had all been planned in this way and decided to try to reconstruct his methods. In the back of Benton’s mind was one of the key experiences of his career: the moment when he walked into Morgan Russell’s studio in Paris and saw his sculpture. The experience had shown him that sculpture and painting could play off each other in a mutually beneficial fashion.

When he first took up sculpture, Benton modeled his figures in full relief, but he soon realized that full relief was not the best approach for coming to a pictorial form of organization since a very slight shift in viewpoint would throw off the entire composition. Consequently, he shifted to deep relief, using as his model both the doorways of Gothic cathedrals and Ghiberti’s famous doors for the Baptistery in Florence, of which he obtained photographs.

As Benton progressed, he further modified Ghiberti’s approach and began to work with a tipped-back plane, a kind of compromise between sculpture and painting, with deeply modeled figures in the foreground and shallower relief as one moved back. “You have to have a certain knack to make them,” Benton later commented in an interview. “Even some sculptors can’t make them if they don’t have a sense of perspective in drawing.”

This unique method made it possible for Benton to create the rhythmic feeling that is the most notable feature of his mature style. Developing such a rhythm through drawings would be an arduous process that would require hundreds of sketches. In clay he could instinctively create a sense of flow and movement and with a few bends and pinches could modify and intensify the sense of rhythm. After 1919 Benton used this method of clay models for every painting that he made.

Benton’s cubic studies (c. 1919–21, top) were inspired both by Cubism and by the drawings of the sixteenth-century Italian

master Luca Cambiaso (bottom). Top: Compositional Study for “Palisades.” (The Benton Trust, UMB Bank, Kansas City, Missouri, original art © T. H. Benton and R. P. Benton Testamentary Trusts/UMB Bank

Trustee/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY. Bottom: Study of a Group of Figures, the Uffizi, Florence.)

He would then make sketches from his statuettes, sometimes filling up an entire sketchbook with studies. Some time before, John Weichsel had lent Benton a German book that reproduced drawings by Luca Cambiaso, a sixteenth-century Italian master, which reduced figures to cubic shapes. Benton recognized that this method made it easier to think about the volumetric form of a composition, and consequently he began making studies of this type. Such cubic drawings are surprisingly difficult to do. You can’t make them by copying the outlines on the surface; you need to draw a clearly conceived concept of the form. That is, you need to conceptualize how the form rests in space and then make a drawing based on this information.

Throughout his career, Benton made many drawings that analyze famous paintings. A good example is his study of the famous

Assumption of the Virgin by El Greco on the main staircase in the Art Institute of Chicago, which is particularly interesting because Pollock made

a drawing of this same masterwork, and it’s fascinating to set the two drawings side by side. But Benton also used this method

for designing new compositions. Indeed, from this time on he never went forward with a major painting or mural without subjecting

the design to this sort of treatment.

Albert Barnes

At this time, Benton finally began to get serious recognition as one of the leading American modernists. One person who helped Benton a great deal at this juncture was the talented modern painter Arthur Carles, a gaunt, hollow-cheeked figure with a dusty beard, whom Benton had known slightly in Paris. Like Benton, he was an enthusiastic talker and drinker. Carles had some power at the Pennsylvania Academy, and in 1922 he organized a show of modern art on the model of the Forum Exhibition, to which Benton contributed. Carles helped him make sales to three wealthy Philadelphia collectors—quite a coup for an artist who had lived from hand to mouth for a decade, either selling nothing or parting with pictures for derisory sums. One of those who purchased his work was the notorious Dr. Albert Barnes, perhaps the leading collector of modern art in the United States. The sale led to an intense if short-lived friendship.

Barnes was a hulking man with a chip on his shoulder who had made a fortune of some twenty million dollars by developing Argyrol, a cherry-red disinfectant then used in clinics and hospitals around the world. Something of Barnes’s temperament is suggested by the fact that his business partner, Herman Hille, who invented Argyrol, sold out to the doctor because he feared that Barnes might murder him.

Once he became rich, Barnes began collecting modern art, in part because he had played baseball as a boy with William Glackens, the Ashcan School painter. He quickly developed a fondness for modern painting, perhaps in part to set himself apart from high society Philadelphia, which he loathed and which tended to favor conservative forms of art. In Paris he visited the Steins and got to know the leading dealers, such as Paul Guillaume. He rapidly became a self-taught expert, convinced of the superiority of his own ideas and taste to those of everyone else.

Today the Barnes Foundation, located in Barnes’s mansion in Merion, just outside of Philadelphia, has probably the greatest

collection of Post-Impressionist painting in the world, with some one thousand masterpieces including 180 Renoirs and 69 Cezannes.

No other figure in the United States had such a seemingly unerring eye for the best in modern art, or such a large checkbook

to indulge his enthusiasm. For an ambitious modernist painter like Benton to connect with Barnes was rather equivalent to

an oilman hitting a gusher. Or at least, so it seemed for a time. When they first met, Barnes and Benton hit it off. Barnes

could hardly have been more enthusiastic about his work. In a note for the show organized by Carles, Barnes said of one of

Benton’s pictures (which he had just purchased):

Corot has never revealed to me a composition as satisfying to a critical analysis as is the composition in a painting by a

young American, Thomas Benton. But to compare Corot at his best with Benton would be an offense to the exquisite sense of

values, the fine intelligence which created the forms in Benton’s picture.

This was the period when artists and art historians were developing the theory that the significance of great art lay not in representational tricks, subject matter, or storytelling but in formal values—what the English critic Clive Bell termed “significant form.” Barnes was a subscriber to this doctrine. What is more, having been trained as a scientist, and being a man of strong and fiercely held opinions, he believed that through careful analysis one could devise exact and definite criteria to explain why a work is beautiful, and therefore art, and another, just slightly different, is not. To demonstrate his theories, Barnes hung his galleries in a thoroughly eccentric fashion, not according to artistic schools but according to the formal relationships he discerned. Alongside the paintings he displayed antique door latches, keyholes, keys, household tools, and objects of furniture, which supposedly had geometric lines similar to those of the paintings.

Benton, of course, had spent a decade analyzing the formal qualities of works of art in a somewhat similar fashion. After Barnes invited Benton to his home, he was so impressed with his intelligence and artistic insight that he invited him back several more times and the two began a lively correspondence. On the last visit Benton brought along Thomas Craven, and Barnes enjoyed their company so much that he suggested they come back every weekend. He noted that he was looking for a writer for a book on the formal qualities of painting. Perhaps Craven could take the project on. He might also employ Benton. Indeed, with his encouragement, Benton began work on a long essay on the mechanics of formal organization in painting.

Benton was never quite sure why Barnes turned on him. “Barnes was a poor talker in man-to-man discussion,” he later commented. “But he brooded on his deficiencies and exploded in his notorious letters.” Benton always suspected that Barnes reacted to his comments about Impressionism, which he did not much care for at the time and which Craven loathed. Benton was showing Barnes his method of analyzing the composition of old master paintings with cubic drawings. When Barnes asked him to discuss the structure of some Impressionist works, of which Barnes owned boatloads, Benton carelessly replied, “Well, that’s kind of difficult, there isn’t much form there.”

Despite this untactful comment, Benton’s last meeting with Barnes was extremely cordial. Barnes provided no clue that something

was amiss. Shortly afterward, however, Barnes made a trip to France, and from Paris he wrote a letter in which he denounced

Benton with heated invective. “Barnes was an amateur psychologist,” Benton recalled, “and he really could be devastating.

Briefly, what he said was that my cockiness with regard to the arts derived from the fact that I was only a runt anyhow, and

runts like me are always combative. He was a vicious bastard, but he did love art.”

Ethel and Denny

It is prophetic that the patronage that Benton found around 1923 to replace Dr. Barnes came from characters of an altogether different type. At the time an actress named Ethel Whiteside was purchasing hats from Benton’s wife, Rita. Ethel had a popular show called The Follies of Coon-town in which she sang “darkie songs” with a group of African American musicians. She lived with a criminal lawyer named Denny, who had become prosperous defending pimps and prostitutes and other unsavory types. The pair lived in a lavish apartment on Riverside Drive with brocade walls and held parties that went on until the late hours of the night almost every evening. Benton and Rita got in the habit of attending.

At some unconscious level the weird assortment of guests—actors, judges, aldermen, and lawyers, perhaps even the occasional gangster—seems to have reminded Benton of the political gatherings he had known as a boy with his father. While a painter was a bit out of place in such a setting, he was forceful enough to hold his own: one evening he chewed out a portly, jowly judge who made fun of him for being an artist, doing so with such eloquence that he gathered a crowd. Before long Denny and Ethel became patrons. In fact, they purchased the largest and most ambitious of his beach scenes, although the formal title, People of Chilmark, was too much for them. Denny christened it Basketball in Hell.

In Denny and Ethel, Benton had found supporters of a new sort: not exactly aesthetic sophisticates, they were nonetheless

wise to the ways of the world and wonderfully, unaffectedly enthusiastic about life. Benton was beginning to look for some

“robust fellows” to connect with, and he was becoming interested in making art that would communicate to them.

* This was not Benton’s only ancestor who was pugnacious. The artist’s namesake, the senator, killed Charles Lucas, who had insulted him, in a duel on Bloody Island, off St. Louis, and also nearly murdered Andrew Jackson in a street brawl, lodging four bullets in his body that were never removed. Remarkably, Jackson and Benton subsequently became friends and political allies, forming common cause against the East Coast politicians led by John Quincy Adams.