Annotations for Ruth

1:1 In the days when the judges ruled. The events of the book take place in the chaotic era reflected in the book of Judges, when Israel lacked central authority, and “everyone did as they saw fit” (Jdg 21:25). Depending upon when the exodus occurred, the span of the period of the judges might be either c. 1400–1050 BC or c. 1220–1050 BC. Not only was Israel embroiled in chaos at this time, but most of the ancient world was as well. The Egyptians, Hittites and Mesopotamians were in general decline; Greece was undergoing political upheaval; and the Sea Peoples (which included the Philistines) were wreaking havoc in the Mediterranean basin. The reasons for these disruptions are difficult to determine, but environmental stresses of some kind in conjunction with a flurry of earthquakes may have contributed to the demise. The deterioration of the major superpowers allowed a number of smaller peoples and states to germinate in the Levant. Among them are the Moabites, Phoenicians, Syrians, Ammonites, Philistines and, of course, the Israelites. famine. Famines were not uncommon in the Levant. Sometimes they could be local as prophesied by Amos (see Am 4:7–8), but the phrase normally implies a wide-spread famine. Several factors could precipitate a famine in addition to lack of rainfall. An adequate amount of rain, but at the wrong time, could destroy the crops. Additionally, plant disease (e.g., Dt 28:21; 1Ki 8:37; Am 4:9; Hab 2:17), insect infestation (e.g., Am 4:9–10; Joel 1) and warfare (e.g., 2Ki 6:24–25; Isa 1:7) could effectively serve as famines. The Bible notes a number of famines, some of which precipitated departures from Canaan—Abraham went to Egypt (Ge 12:10); Isaac sojourned in Gerar (Ge 26:1); and Jacob and his family descended to Egypt (Ge 43–50). Overall, the pattern of famine and plenty in the Levant is unpredictable. Bethlehem. The name means “house of bread.” Ironically, the house of plenty has failed Elimelek, forcing his exodus to Moab. Bethlehem is about five miles (eight kilometers) south of Jerusalem on the main north-south road that passes along the ridge of the central mountains. The area is generally productive with wheat, barley, almonds and grapes, which may have factored into the significance of the town’s name. It would become the birthplace of David. live for a while. The Hebrew word here is often rendered “sojourn” and is a technical social term applied to a class of people who are neither native nor simply foreigners living in the land. They had no blood ties to the residents and only had legal rights as the dominant peoples permitted, which were often whimsically granted and withdrawn. The people of Sodom refer to Lot in this way and use it as a slur (see “foreigner” in Ge 19:9).

1:2 names. With the exception of the wordplay that Naomi injects regarding her own name (v. 20), the names of the major personalities—Elimelek, Naomi, Mahlon, Kilion, Ruth and Orpah—have neither meanings nor etymologies that play literary roles in the narrative. The equivalents of Elimelek, Naomi and Kilion are preserved in Ugarit, Amorite and/or Akkadian (demonstrating that they are authentic period names), while Mahlon, Ruth and Orpah have not been identified. Ephrathites. The matriarch, Rachel, had died on the way to Ephrath (Ge 35:16–19), which was an earlier name of Bethlehem (familiar to us from Mic 5:2, a well-known passage read around Christmas). The use of Ephrathite may reflect an old aristocratic family of Ephrath/Bethlehem from which Elimelek descended.

1:3 Elimelek . . . died. The hazards of widowhood in antiquity were great. In most rural areas, women would have had little opportunity to pursue independent careers, and therefore overwhelmingly depended upon their husbands for sustenance. Women certainly had significant roles in the household, but these usually did not extend to commercial enterprises, contrary to the idealized description of the noble woman of Pr 31. Upon her husband’s death, the widow normally relied upon her sons for support; if she had none, she might have to sell herself into slavery, resort to prostitution or die. It is in part to prevent this harshness for which the guardian-redeemer legislation exists (Lev 25:39–55). The Mosaic Law was concerned for the widows and the poor (Dt 10:17–18; cf. Ps 68:5; 146:9; Jer 49:11), and issued instructions for their preservation (e.g., Ex 22:22–24; Dt 14:28–29; 24:17–20; 26:12–13; 27:19). Many of these concerns with widows, the poor and orphans are mirrored in surrounding cultures from whom laws and customs have been preserved; among them are laws from the Code of Hammurapi, instructions relative to widows and orphans in Egypt and justice for the widow and orphan in the gate at Ugarit.

In view of the events that followed—particularly the deaths of Naomi’s two sons—we may infer that she is stripped of all male protection. Her plight, then, would often be connected to that of the orphan and foreigner (e.g., Mal 3:5) and the poor (e.g., Isa 10:2). The lapse of ten years (v. 4) implies that Naomi is past childbearing age, or at least near the end of such, so that her prospect of finding a husband would be significantly reduced. Her decision to return to Bethlehem was the most reasonable option; there she might at least find sustenance by gleaning if no extended family members were to care for her.

If the marriages in the narrative followed typical ancient Near Eastern tradition, Naomi probably had married in her mid-teens and had likely borne her two sons by age 20. The sons would have married a little earlier than age 20 to young women similarly in their mid-teens. By the time she decides to return to Judah, Naomi is likely in her mid-40s and Ruth and Orpah are likely in their mid- to late 20s.

1:8 mother’s home. The OT implies that the mother’s house has to do with preparation for marriage (Ge 24:28, SS 3:4; 8:2). This corresponds to Egypt and Mesopotamia, where the mother was the protector of the daughter and the advisor and supervisor in matters of love, sex and marriage. The suggestion to return to their mother does not primarily encourage seeking legal protection (Ruth’s father is still alive, cf. 2:11), but rather presents the option to have a new family.

1:11 sons . . . become your husbands. The Bible provides specific legislation for family preservation, often called levirate marriage (Dt 25:5–10; see the article “Levirate Marriage”)—if a man married a woman and he died before there were offspring, his brother would marry the widow and raise up children in the name of the deceased. Since Naomi does not mention the prospect of marrying her husband’s brother, technically, her proposed scenario would not be levirate marriage, since the husband she might hypothetically secure would not, in a patrilineal society, produce brothers to her deceased sons. Instead she emphasizes how futile was any prospect of securing husbands for her widowed daughters-in-law, in contrast to the implied resources of their “mother’s home” (v. 8; see note there).

1:15 her people and her gods. While “people” and “gods” may refer to her personal allegiances, they also may extend to her tribe’s social and religious associations. Ancient societies often had a hierarchical slate of deities who resided in their area—sometimes connected with geography or geographic features. This is indicated when the Aramean king’s officials described Israel’s gods as “gods of the hills” and not of “the plains” (1Ki 20:23). A god’s domain, however, might expand geographically through conquest as indicated in Ashurnasirpal’s bombast of himself and the sponsorship of a host of Assyrian deities. These national gods apparently were often considered beyond the reach of the common person, who alternatively appealed to an array of lesser deities and spirits who were more easily accessible and task specific—hence the proliferation of the personal family worship that may have been at odds with the national religious expression.

1:16 your God my God. The national god of Moab was Chemosh. Mesha, a later Moabite king, commented that Chemosh had been angry with the land and permitted Omri to subdue the country. Chemosh was an ancient god in the Levant for whom we have evidence as early as the late third millennium BC at Ebla. We have no evidence of his perceived character at the period, although he may have been a god of war similar to the Mesopotamian god, Nergal. Ruth’s statement suggests that she will adopt the worship of Naomi’s people in Bethlehem. This is an expression of her loyalty to Naomi, and it would be the general practice of someone joining a new family and community in a new area. Though the high God of the region is Yahweh, the syncretism of the judges period would likely have featured gods at various family and clan levels. Ruth would not be able to continue worshiping her gods (Chemosh or any others), for there would not have been sacred places dedicated to them. Ruth’s decision is born of loyalty to Naomi, not necessarily of any theological convictions about Yahweh as the one true God. However, it is enough of a foothold for Yahweh to reveal himself.

1:17 there I will be buried. Ruth’s commitment to leave her family for a land where she apparently has never been, potentially totally isolated from her own kin, commands admiration and respect. While she has probably become familiar with some Hebrew customs and beliefs, to saturate herself in the different culture has dimensions that one can only appreciate by experience. Some suggest that her loyalty surpasses that of Abraham, since he was called by divine direction (Ge 12:1–5) and Ruth was not. To most Westerners, there is usually little emotional trauma in being buried away from the family plot. Such a casual approach to death was unknown to the people of ancient Canaan. The Bible often refers to death as being gathered to one’s people (e.g., Ge 25:8, 17; 35:29; 49:33; Nu 20:24, 26; Dt 32:50), and Jacob and Joseph gave specific instructions that their remains be conveyed to the family homeland (Ge 49:29–32; 50:24–26). These requests are apparently not unique to the Israelites. Archaeology has uncovered a number of cemeteries, many of which yield evidence that the deceased had passed away elsewhere and their bones had been interred in the cemetery sometime after death and decomposition had occurred. Our text gives no indication that Naomi had brought her husband’s and sons’ remains back to the family plot in Bethlehem, but if she did not, she likely was returning with them on this journey.

A proper burial was a matter of great concern for people in the ancient world. Goals were to keep the deceased connected to the community of living relatives and descendants as well as to help them transition into the community of the ancestors who had already died. The maintenance of the dead was a common practice as implied in the often elaborate tombs designed to accommodate the extended family. Continued care for the dead was a common practice in the ancient world and was believed to affect the afterlife of the deceased.

1:19 stirred. The Hebrew word elsewhere denotes considerable excitement and commotion (cf. 1Sa 4:5; 1Ki 1:45). Ancient towns were little more than small villages. Demographic studies indicate that the typical village had a population of only a few hundred. Additionally, the population of the town may have diminished because of the famine—either by death or by its inhabitants emigrating, as Elimelek and his family had done.

1:22 barley harvest. Barley and wheat were usually sown at the same time, but barley matured a month before wheat and was harvested from mid- to late April. Barley was not the preferred grain of consumption—it yielded a course, hearty bread. Since barley matures first, though, it is suitable as the firstfruits offering (Lev 23:10). The arrival of the barley was a time of rejoicing, and it heralded the prospect of security as the remaining crops would come in.

2:1 man of standing. The Hebrew phrase used here is often rendered “mighty man of valor” (cf. “best fighting men” in Jos 10:7; “valiant soldier” in 2Ki 5:1), but sometimes it simply refers to a person of ability (1Ki 11:28) or of wealth (2Ki 15:20). The connection with wealth suggests that the “man of standing/valor” was wealthy enough to leave his place of livelihood, having his own weapons of war to serve as necessary when there was not a standing army. Even though there is no evidence of military conflict or turmoil in the book of Ruth, Boaz’s description as a man of standing may be significant, since the events are placed within the context of the chaos and anarchy of the period of the judges (Ru 1:1), when there was occasional need to call people for military duty (cf. Jdg 3:28–29; 4:10; 7:1, 23). clan of Elimelek. The clan was a social grouping in size between that of the tribe (e.g., Judah) and that of the extended family. The clan definition was based on descent from a common ancestor and from within this context the function of the guardian/redeemer (cf. Lev 25) of the narrative will unfold. The clan would normally be responsible for maintaining the social and economic survival of the relatives and in times of crisis would even contribute personnel to the defense of the emerging tribal nation.

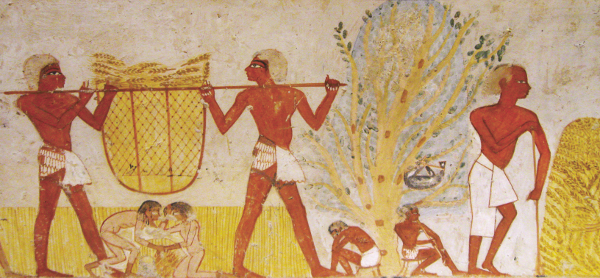

2:2 pick up the leftover grain. Commonly called gleaning. Mosaic Law decreed that landowners were not to harvest the full extent of their fields, but were to leave produce in the hard-to-reach areas. The remaining harvest was for the poor and foreigners who might be in the land (Lev 19:9–10; Dt 24:19–22). Ruth expects to gather the cut remnants that the reapers have accidentally dropped. Obadiah (Ob 5) and Jeremiah (Jer 49:9) allude to the expectations of gleaning in their indictments of Edom. in whose eyes I find favor. Even though Mosaic Law prescribed the landowner to permit gleaning, part of the challenge of the period of the judges was that the people did not generally follow God’s law. Ruth’s statement implies not only an awareness of etiquette to request permission, but also the potential danger to herself, particularly as a foreigner. Later prophets reveal that the Israelites did not always follow God’s direction relative to the poor and oppressed (Isa 1:17; Am 5:10–15; 8:4–6; Mic 3:1–3), and almost certainly this abuse would often manifest itself in the refusal to allow them to glean. Corroboration of this is the Egyptian instruction from the Ramesside period: Do not “pounce on a widow when you find her in the fields. And then fail to be patient with her reply.” It is not clear if this instruction reflects a widespread custom or law in Egypt, or if it simply represents Amenemope’s perception of civility and humanitarianism.

2:3 behind the harvesters. Whether the harvesters were from Boaz’s household cannot be ascertained. The Bible notes that natives and foreigners might hire themselves out for work (Dt 24:14) either on a daily basis (Lev 19:13; Dt 24:15; cf. Mt 20:1–16) or annually (Lev 25:53). The Laws of Eshnunna specified a shekel of silver for a month’s wages, plus a grain provision. The Code of Hammurapi decrees a per diem wage—for the first half of the year, it was to be six barleycorn of silver per day and for the second half, five barleycorn of silver per day. We do not know the pay scale for the time of Ruth in Judah. Harvesting crops apparently was not a favored occupation (cf. Job 7:1–2; 14:6), and the person’s welfare would inevitably be at the mercy of the overseer (Jer 22:13; Mal 3:5). a field belonging to Boaz. People typically lived in small towns or villages, which provided safety as well as a sense of community, especially since the people were usually tribally related. The population of the town seldom exceeded a few hundred. The fields were away from the town and it was necessary for the people to leave the security of the town to work in the fields. The fields were marked off in family plots, often with small piles of stones serving as boundary markers. It would be somewhat easy for an unscrupulous person to move these stones over a little at a time to increase his land holdings at the expense of a neighbor. Reflecting this reality, the Bible has injunctions against illicitly moving boundary markers (Dt 19:14; 27:17; Pr 22:28; 23:10; cf. Job 24:2; Hos 5:10). A similar prohibition against land theft with instructions for compensation appears in Hittite laws. The production of these small piles of stones, and sometimes low walls, were also a convenient means by which to remove the stones from the cultivable fields.

2:4 “The LORD be with you!” “The LORD bless you!” The exchange of greetings imploring the Lord is not unusual. It may denote an element of devotion, but it may also simply have been a customary greeting. In this text, the reader is certainly supposed to read significance in it even if it is conventional. In Ps 129, the psalmist uses agricultural imagery to describe the interaction with his enemies; the final verse (Ps 129:8) implies that a blessing including the divine name was common. One greeting in the Hebrew Bible was simply “shalom,” meaning “peace” (cf. Jdg 6:23; 1Sa 25:6; 2Sa 18:28).

2:5 the overseer. The Hebrew word used here is sometimes translated “young man,” but the term encompasses much more. Ugaritic and Egyptian sources use a cognate word to refer to people of military rank. Similarly, people in the Bible who are so designated are often servants or retainers of some kind (Nu 22:22; Jdg 7:10–11; 19:3; 2Ki 4:12) or military personnel (Ge 14:24; 1Sa 25:5; 2Sa 2:14; 1Ki 20:14). It can also apply to someone who manages an estate, such as Ziba, who had custody of Saul’s estate (2Sa 9:9; 19:18). As far as age is concerned, the age of demarcation appears to vary depending on the function of the person involved—for military service, it was age 20 (Ex 30:14; Nu 1:3, 18); for Levitical service outside the tent of meeting, it was age 25 (Nu 8:24); for service in the tent of meeting, it was age 30 (Nu 4).

2:7 from morning till now. The Hebrew text is difficult to decipher. The NIV has opted for a rendering that describes the agricultural custom of rising early to work in the fields. Farmers typically rise at or before dawn to take advantage of the cooler morning temperatures. In pre-industrial societies, and especially in a hot climate like that of Israel, it would be normal to take an afternoon break during the heat of the day and resume the field work in the later afternoon. This is part of the context for David’s late afternoon walk on his roof after his rest (2Sa 11:2). short rest in the shelter. Again the Hebrew is difficult. The NIV has opted to render the verse to reflect Ruth’s industriousness. She has not stopped working “except for a short rest in the shelter.” Work in the hot sun can quickly drain one’s energy. The shelter was a kind of brush arbor set up as a break shade for the workers. Because of Israel’s low humidity, retreat into the shade yields a dramatic differential in temperature, since the dry air rapidly evaporates the perspiration and accentuates the cooling effects.

2:9 follow . . . after the women. It appears there was a division of labor, the men doing the cutting (v. 15) and the women doing the binding (vv. 8–9), although this separation is not necessarily absolute. men not to lay a hand on you. Ruth’s presence on the scene as a stranger and especially as a foreigner would naturally draw attention and almost invite abuse by some in society. lay a hand on. The Hebrew word carries several nuances including to strike (see Ge 32:25, 32; Jos 8:15 [“be driven back”]; Job 1:19), to inflict injury (see Ge 26:11, 29) and to have sexual relations (see Ge 20:6; Pr 6:29). Unless Boaz suspected his employees to be of the basest sort, it is unlikely that sexual relations (i.e., rape) would be the point of his prohibition; more likely it was that they were not to strike or abuse her or inflict upon her verbal abuse (cf. the Egyptian “Instruction of Amenemope” in the note on v. 2). water jars. The young men were to permit her to drink from the jars they had filled. Without a readily available water supply in the field, it was necessary to prepare for the day’s activities. While not necessarily exclusively so, drawing water was commonly a woman’s job (Ge 24:11, 13; 1Sa 9:11). Ugaritic materials reflect the activity as predominantly a woman’s task. The Israelites sometimes coerced foreigners into the job (Dt 29:10–11; Jos 9:21–27).

2:10 bowed down with her face to the ground. While we cannot be absolutely sure of the posture involved, the Black Obelisk depicts Jehu of Israel bowing before Shalmaneser III with his face on the ground.

2:12 under whose wings. In this case, Boaz likely simply alludes to the protective covering of the Lord’s care. The Lord elsewhere is portrayed as providing such protection (Ps 36:7; 57:1; 61:4; 91:4). Occasional artistic depictions of deities spreading their wings over their subjects can be seen in a Syrian goddess spreading her wings over two children who nurse at her breasts. An Egyptian statue depicts Horus as a falcon hovering behind the king, Khafre, and another shows the wings of Isis protectively surrounding Osiris. Boaz’s imagery might draw from the wing-protected ark of the covenant law with its cherubim (Ex 25:17–22).

2:14 At mealtime. The day’s meals normally began with a light breakfast and a light noon meal such as reflected in this narrative. The evening meal was the main meal of the day and usually consisted of basically a one-pot stew mainly of vegetables; the stew was sopped with bread. wine vinegar. May have been a type of vinegar-based sauce. An inscription preserved from Arad lists this commodity (Hebrew homets) as being requisitioned along with wine; however, earlier Ugaritic materials seem to list it as a synonym of wine. Linguistically, the item, alternatively, could render a commonly used chick pea sauce, hummus, prevalent through the Mediterranean world into which bread is dipped. The roasted grain was a common addition to the meal (1Sa 17:17; 25:18; 2Sa 17:28).

2:17 threshed the barley. To thresh this personal harvest for herself and Naomi, Ruth beat the grain with a stick to separate the grains from the chaff (cf. Gideon in Jdg 6:11). It would be necessary for her then to winnow it as well (see note on 3:2). Her take for the day was impressive—an ephah (about two-thirds of a bushel, or 23 liters) is an exceptional quantity and implies that the workers complied with Boaz’s request (vv. 15–16). This was the same amount that Jesse instructs David to deliver to his three brothers serving in Saul’s army (1Sa 17:13–17).

2:20 the living and the dead. Some cultures worked to maintain the dead by giving food offerings and sacrifices on their behalf; there is no indication that Naomi has this in mind—she more likely alludes to God’s preservation of the memory of the dead (i.e., Elimelek, Mahlon and Kilion) by taking care of their widows (i.e., Naomi and Ruth). She recognizes that Boaz is a potential source of hope as their guardian-redeemer (Hebrew goel). guardian-redeemers. This role was multifaceted and served to stabilize a disrupted family circumstance. Mosaic Law prescribed that the guardian-redeemer reacquire property lost by family members who had fallen on hard times (Lev 25:25–30; cf. Jer 32:6–15). He also was to redeem relatives who, because of poverty, had sold themselves into slavery (Lev 25:47–55). In addition, he was to avenge relatives who had died at the hands of others (Nu 35:12, 19–27; Dt 19:6, 12; Jos 20:2–3, 5, 9), be the recipient of payments owed to deceased relatives (Nu 5:8) and generally serve to alleviate wrongs that relatives might not be able to alleviate for themselves (Job 19:25; Ps 119:154; Pr 23:11; Jer 50:34; La 3:58). The legislation says nothing explicitly regarding taking the wife of the deceased as part of the redemption procedure, although it appears that the Israelites sometimes understood a connection between the two.

2:23 barley and wheat harvests. The time involved would normally be two to two and one-half months, taking the wheat harvest into June. If the narrative is chronological, the winnowing of barley does not commence until ch. 3; it appears the barley winnowing was put on hold until the wheat harvest had come in. If this is the case, it implies a significant harvest in view of the recently terminated famine.

3:2 winnowing barley. Winnowing was often done as a community activity. Winnowing takes place after the threshing (see below), and it is a very labor-intensive process to separate the grains from the plant stalks. The process was conducted typically outside of the town where the person, using a pitchfork, would throw the mixture into the air. The breezes blew away the unwanted, lighter components (cf. Hos 13:3), allowing the heavier grains to fall to the ground. The process would be repeated until the grains were relatively free from the plant stalks. The breezes usually came up in mid-afternoon and died out about sunset; it is possible that Naomi’s reference to Boaz winnowing at night accommodates the festivities that normally followed a successful harvest and winnowing. Transport of the grain to the threshing and winnowing floor was either in animal-drawn carts (cf. Am 2:13) or in baskets. threshing floor. A large flat area, usually bared bedrock, slick from the polishing effect of the intensive activity, with the straw acting as a polishing agent. It was situated to take advantage of the prevailing winds, which were critical for the process. Sometimes it was near the city gate (1Ki 22:10; Jer 15:7); Ugaritic literature also cites the placement of a threshing floor near the gate. Threshing could be done several ways. Ruth had beaten out her fairly small volume with a stick (see note at 2:17). A larger volume, however, required more intensive and efficient threshing. Sometimes animals walked over the grain and their hooves beat the grain to separate the grain from the stalk (cf. a metaphoric allusion in Mic 4:13). Mosaic legislation demanded that the animals be allowed to eat of the harvest (Dt 25:4). A more efficient tool was to use a threshing sledge, which would be pulled by an animal or two (cf. the metaphor in Isa 41:15). The sledge consisted of two to three wide boards with upturned ends to slide easily over the grain; the underside of the boards would have holes drilled or slots cut into them into which teeth of flint or iron were driven. The teeth would separate the components of the grain. Isaiah also alludes to the wheels of carts along with the animals hooves being used to thresh (Isa 28:28).

3:4 uncover his feet. The instruction is seen by some as a double entendre. Sometimes the Hebrew word translated “feet” is a euphemism for the genital region (see Isa 7:20; Eze 16:25; and perhaps Ex 4:25; Jdg 3:24; 1Sa 24:3), but most of the time “feet” simply means feet. Complicating the interpretation, however, is the use of “uncover” (glh) which sometimes referred to sexual relations (Lev 18 [14 times]; Lev 20 [6 times]; Dt 22:30; 27:20; Eze 16:35–39). Nevertheless, Naomi instructs Ruth to uncover “the place of his feet,” and given the noble character reflected of both Boaz and Ruth, there is no reason to infer that anything more than uncovering the feet occurs. The meaning of this apparently significant action is unknown to us.

3:7 far end of the grain pile. Boaz probably remained at the threshing floor to protect against thieves.

3:9 Who are you? As to what startled Boaz awake is not revealed, but it likely was the subconscious realization that someone was nearby. Spread the corner of your garment over me. Ruth’s request is an idiom for marriage. The phrase is the same as applies to marriage when God later described his marriage to Israel (Eze 16:8). The imagery brings to mind Boaz’s own blessing of coming under the Lord’s wing for protection (2:12). Ruth explains that the invitation is important because he is her “guardian-redeemer” (see note on 2:20). corner of your garment. Applies to either a wing or the edge of a garment.

3:13 Stay . . . the night. The Hebrew word does not have sexual connotations.

3:14 No one must know. See previous note. Obscurity is important for propriety, but it is also important that rumors of immorality do not interfere with the day’s legal proceedings

3:17 six measures. The “measure” is not identified, but it would not have been the ephah since six ephahs would equal approximately 200 pounds (90 kilograms). The seah is more likely; six seahs would equal 60–90 pounds (27–41 kilograms). An alternative would be an omer, which was approximately one-tenth of an ephah, in which case the amount would be a little over half the quantity she had gleaned in her first outing (see 2:17 and note).

4:1 the town gate. See note on Ge 19:1. guardian-redeemer. See note on 2:20.

4:2 elders. References to elders who oversee the people of antiquity appear in the Gilgamesh Epic and in Hittite law. The Bible indicates that Moab and Midian had elders serving a similar function (Nu 22:4, 7) as did the Gibeonites (Jos 9:11). Over time, the term came to apply not only to those of a certain age, but to those who administrated the affairs of the community. They were assumed to be people who had experienced sufficient vicissitudes of life to be able to tap into those experiences to guide the community (1Ki 12:6–11; Job 12:20; Jer 26:17–19). Additionally, they sometimes represented the people before God (Lev 4:13–15), and would oversee murder trials and questions of asylum (Dt 19:11–12; 21:1–9; Jos 20:1–6) and disputes regarding virginity (Dt 22:15–19). They also sometimes served as social witnesses to issues of the guardian-redeemer and levirate marriages (Ru 4:9–11; Dt 25:5–10). The Bible notes that there were elders over tribal and clan affairs (e.g., Jdg 11:5), as well as over national affairs (Dt 31:28). In addition, cities had their own appointments (Dt 19:11–12). How many elders a town should have is not indicated in the Bible. Gideon was informed that Sukkoth had 77 elders and officials (Jdg 8:14). This statement in Ruth (i.e., “ten of the elders”) indicates that there were more than ten for Bethlehem.

4:5 the dead man’s widow. See the article “Levirate Marriage.”

4:6 I might endanger my own estate. The man fails to elaborate how serving as the guardian-redeemer with Ruth as part of the deal would endanger his estate. Since the purpose of the levirate marriage was to perpetuate the name of the deceased, the inheritance would be through another’s line than the guardian-redeemer himself. An investment to redeem the land for Naomi, who was apparently past childbearing age (1:11–13), would likely keep the property in his own line, and would be an attractive business proposal, but the prospect of marrying Ruth, who came with the property and the implied responsibilities, would indicate that not only would the investment to redeem the property be forfeited to any offspring that might be born, but there would be the added burden of supporting Ruth and Naomi, as well as any additional offspring that might come from the union.

4:7–8 took off his sandal . . . removed his sandal. The text implies that the guardian-redeemer relinquished his sandal to Boaz. The image perhaps derives from property rights and the right of the person who owns a piece of land to be the one who walks on it. God had revealed to Abraham that wherever he might walk in Canaan, the land would belong to him (Ge 13:17). This foot-placement motif is reflected in the Nuzi materials in which “to make a transfer of real estate more valid, a man would ‘lift up his foot from his property,’ and ‘placed the foot of the other man on it.’ ” With similar imagery, God declares possession of Edom with the metaphor of casting his sandal over the land (Ps 60:8; 108:9).

4:7 earlier times. Indicates that some time has passed from the events of the narrative and when it was recorded, although the Hebrew term sometimes refers to a single generation’s separation (cf. Job 42:11).

4:10 maintain the name of the dead. Similar explanation appears in the levirate marriage legislation (Dt 25:6). “Name,” however, does not serve just as nomenclature; it also refers to being remembered and honored, a kind of eternal life in having offspring to connect with the deceased. Its broader use has to do with inheritance and “the reality and significance of a man’s deeds and life.” If a man had no sons, the name might be preserved through daughters, as implied in the request of Zelophehad’s daughters and their petition to Moses (Nu 27:1–11); however, they were required to marry only within their own tribe (Nu 36).

4:17 Naomi has a son! It is possible that this refers to a legal adoption, but it more likely recognizes that Naomi is the legal mother of the child (Boaz substituting for Elimelek) and that she will play a significant role in his upbringing.

4:18–22 Genealogies in the ancient world served to communicate connectedness and identity. Sometimes a genealogy may associate a person to someone well-known in their past. Here, the genealogy indicates how the famous king David descended from these very unusual roots. The point is not that he descended from a Moabite woman, but that he descended from a line in which there was faithfulness, in contrast to the tenor of the judges period.