Annotations for Mark

1:1 good news about Jesus the Messiah. Especially in the context of Isaiah’s message of Israel’s restoration (Isa 40:3), quoted in v. 3, “good news” evokes the promised restoration (Isa 40:9; 61:1). This was good news of peace for God’s people, good news of the kingdom (i.e., good news that he reigns, hence would restore his people; Isa 52:7). Thus Jesus announces good news that the time for this kingdom has drawn near (vv. 14–15).

1:2–3 In both of these Biblical quotations, one prepares the way for God himself. Although Mark quotes both Malachi (Mal 3:1 in v. 2) and Isaiah (Isa 40:3 in v. 3), he gives the name only of the more prominent prophet. He may wish to draw attention to Isaiah partly because of the connection he intends with Isaiah’s context (see note on v. 1). Ancient interpreters often treated Scripture as a seamless whole and often linked texts based on a common key word, phrase, or concept (here, “prepare the way”). Malachi referred to one who would come like Elijah (Mal 4:5–6); Mark recognizes that this applies to John the Baptist (cf. v. 6; 9:11–13). The quoted verse from Isaiah also speaks of one preparing the way, and the way in the wilderness described the promised new exodus, a new era of salvation and restoration for God’s people (Isa 11:16; 19:23–25; 43:16–21; 51:10–11; cf. Isa 49:8–12; 57:14). The tradition is undoubtedly Judean and thus very early, long before John’s ministry in the wilderness; the Qumran community, in the desert southeast of Jerusalem, also applied Isa 40:3 to their own mission.

1:4 wilderness. The wilderness was a place of hardship, but it was the safest place to draw crowds. In the context of v. 3, it evokes the promised new exodus of salvation (cf. Isa 40:3; Hos 2:14). No one outside of Judea would have known to speak of someone baptizing in the Jordan (v. 5) as being in the wilderness, but the fertile area around the Jordan quickly gave way to wilderness beyond it. baptism. Jewish people had various ritual immersions; one, the immersion of Gentiles converting to Judaism, involved a wholesale turning to a new way of life. See the article “Baptism.” repentance. Jewish people valued repentance; John here may evoke the prophets’ calls to Israel to “turn” back to God (e.g., Isa 44:22; Jer 3:12, 14, 22; Hos 12:6; 14:1–2; Joel 2:12–13; Zec 1:3–4; Mal 3:7). forgiveness of sins. One of God’s promises for the restoration time (Isa 43:25; 44:22; 53:5, 11–12).

1:5 Jordan River. Because crossing the Jordan signaled entering the promised land in Jos 1:11, here it might evoke the promise of restoration. More certainly, it was the one large body of water suitable for John’s mission.

1:6 clothing made of camel’s hair . . . a leather belt. John’s leather girdle recalls Elijah (2Ki 1:8), fitting Mark’s Biblical introduction of John in v. 2. Like his location, his clothing and diet suggest a rugged lifestyle. A garment of camel’s hair was a garment of sackcloth, indicating mourning, likely over the nation’s sin. locusts. Some Jewish people ate locusts (which were kosher), but only someone who lived completely in the wilderness might be limited to such a diet. wild honey. Obtained after smoking wild bees from their hive.

1:7 sandals I am not worthy to . . . untie. Assisting others with their sandals was normally the sort of task that only a low-level servant would normally perform; the prophets were “servants of God” (2Ki 9:7; Jer 7:25; 26:5–6; 29:19; 35:15; 44:4), and Jesus considered John the greatest prophet (Mt 11:11) but John considers himself unworthy even for this role. The one whose way he prepares is thus none other than God himself (cf. vv. 2–3).

1:8 baptize you with the Holy Spirit. One promise for the time of restoration (cf. vv. 2–3) was the pouring out of God’s Spirit (Isa 32:15; 44:3; Eze 39:29; Joel 2:28–29); only God himself could pour out God’s Spirit (cf. v. 7).

1:9 from Nazareth in Galilee. Outside of their own communities, people were often named for the community they came from. By some modern estimates, Nazareth, like many Galilean villages, had only some 500 residents (although sparser habitation away from the village’s center may not be counted). baptized by John. Being baptized “by” someone presumably meant under their supervision; given what are thought usual practices at the time, Jesus may have bent himself forward.

1:10 heaven being torn open. The heavens could be opened for revelations (Eze 1:1). Spirit descending. The Spirit’s coming begins the promise of v. 8. like a dove. See note on Mt 3:16.

1:11 voice came from heaven. A heavenly voice at Isaac’s sacrifice spared Isaac, Abraham’s beloved son (Ge 22:2, 12, especially v. 12 in the Septuagint, the pre-Christian Greek translation of the OT); God also named David’s dynasty as his son (Ps 2:7). Later rabbis subordinated the value of heavenly voices to prophets in Scripture, but here the heavenly voice confirms the prophetic one (v. 3).

1:13 forty days. As Israel faced testing for 40 years in the wilderness, they would also pass through the wilderness during the promised new exodus (see vv. 2–3). Here Jesus endures the testing 40 days before beginning the promised restoration. wild animals. Cf. protection from animals in Eze 34:25; Da 6:22.

1:14 prison. For John’s imprisonment, see 6:17. good news. See note on v. 1.

1:15 time has come . . . kingdom of God has come near. Although similar language applied to other foreordained events (e.g., Eze 7:7), in context the “time” here refers to the time of God’s promised reign (e.g., Isa 52:7; cf. 49:8); “kingdom” means “reign.” To be ready for that time, people needed to “repent,” i.e., turn (see note on v. 4). good news. See also v. 14. See note on v. 1; Isa 52:7, which speaks of both “good news” and God’s reign, may be especially in view here. Sometimes a theme would bracket a section, and good news may bracket Mark’s introduction.

1:16 Sea of Galilee. Only local people called this lake a “sea” (as the Gospels usually call it in Greek); the usual usage in the Gospels reflects the memories of Jesus’ early Galilean disciples. Fishing was a major occupation on the Sea of Galilee. Many believe that commercial fishermen, although not elite, were usually better off economically than the peasants who comprised the majority of Galileans.

1:17 Come, follow me. Only the most radical teachers called disciples, rather than waiting for disciples to choose them (e.g., 1Ki 19:19). follow. Lit. to “come after” a teacher was to take the posture of a disciple.

1:19 preparing their nets. Nets needed care and even periodic repair; winter was harder on them than summer.

1:20 hired men. A family business that employed hired servants had ample income. followed him. To abandon a family business, which the sons would normally expect to inherit, had dramatic implications for the family as a whole.

1:21 Capernaum. A fishing town; some estimate its population at about 1,500, perhaps three times that of Nazareth. synagogue. Archaeologists have found some of this synagogue beneath a later one constructed on the same site. Jewish people gathered in synagogues on the Sabbath to pray and study Scripture.

1:22 teachers of the law. These men often cited the opinions of earlier teachers.

1:23 possessed by an impure spirit. Although rarely, some early Jewish sources explicitly associated evil spirits with impurity.

1:24 What do you want with us . . . ? Lit. “What (is there between) us and you?” (cf. 5:7)—a phrase that emphasizes distance and often hostility between the speaker and the one addressed (Jdg 11:12; 1Ki 17:18; 2Ki 3:13; 2Ch 35:21 in the Septuagint, the pre-Christian Greek translation of the OT). I know who you are. In some magical texts, those trying to control spirits declare, “I know you” or “I know your name.” Here the spirit might try to use such knowledge to ward off Jesus—clearly unsuccessfully.

1:26 with a shriek. People often expected spirits to display their departure dramatically. People often tried to expel demons through incantations or strong odors; Jesus’ ability to expel demons simply by commanding them was extraordinary and invited amazement.

1:28 spread quickly. Villages were often close together and rumors spread rapidly.

1:29 home of Simon and Andrew. Some homes in Capernaum were free standing, but many were built around courtyards shared with other homes. Sometimes extended family stayed in a home together (note here Simon’s brother Andrew is mentioned as an owner of the house). Newly married couples sometimes had a room on the roof of the groom’s parents; because many men died in their 50s, families might also need to take in a widowed mother (v. 30).

1:30 fever. Fevers were common; one of the most common causes of fevers in the ancient Mediterranean world was malaria, which could be serious and did not normally disappear suddenly.

1:32 after sunset. Because one should not carry loads on the Sabbath, which it is (v. 21), people wait until sundown (Jewish people reckoned days from sundown to sundown) to bring the afflicted to Jesus. sick and demon-possessed. The promised restoration (see note on vv. 2–3) included healing (Isa 35:5–6). Mark’s series of miracle stories could remind ancient hearers of the series of miracle accounts surrounding Elijah and Elisha (especially 1Ki 17–19; 2Ki 1–8).

1:33 whole town. Ancient writers often used hyperbole; some estimate Capernaum’s population at roughly 1,500. at the door. Homes were often small, though Peter’s may have been larger (fishermen could earn ample incomes).

1:35 house. Many people could be staying in a home at one time (see note on v. 29). solitary place. Most homes were tightly packed together; and villages along the Sea of Galilee were often close together. Finding privacy (cf. Mt 6:6), with so many people desiring attention (v. 33), required rising before others did (in that culture, normally at sunrise, which at various times of year averaged about 5:30–6:30 a.m.).

1:40 leprosy. The category of what was called leprosy in the ancient world included severe skin conditions that typically led to isolation from society (in most societies; for Jewish society, see Lev 13:1–14:32). Out of respect, as elsewhere in Scripture (Ge 18:27, 30–32; cf. 2Sa 10:12; Da 3:18), this man recognized Jesus’ prerogative to choose, even while pleading for him to act.

1:41 touched the man. Because lepers were unclean (Lev 13:45–46), anyone who touched them contracted temporary ritual impurity. Jesus here touches someone unclean (cf. Mk 5:31, 41) to cure him. For one Biblical precedent for healing a leper (in that case without touching him), see 2Ki 5:10–14.

1:44 don’t tell this to anyone. Although men of influence often competed for honor, ancients respected people who did not seek their own honor; moreover, Jesus has already been having trouble with crowds (v. 33). show . . . the priest. See note on Mt 8:4

1:45 Where valuable medical resources are lacking, people flock to what they believe might cure them; in antiquity, e.g., including in Galilee, people flocked to hot springs hoping to be cured. News of the miraculous healings naturally prompted many to seek similar healing.

2:2 no room left. Most homes in Capernaum were small (see note on 1:29).

2:4 opening in the roof. Logs used as roof beams supported most Galilean roofs; reeds or branches were laid across these logs, then the whole was overlaid with packed mud or clay (contrast Lk 5:19). Such roofs were stable enough for walking, but one could break through them by digging. A staircase or in some cases a ladder led to the roof.

2:7 He’s blaspheming! Although priests might pronounce God’s forgiveness, only God could forgive sins (Mic 7:18). Later rabbis defined blaspheming more narrowly (cursing with the divine name, as in Lev 24:11), but the term used here can mean any demeaning speech, including speech dishonoring God.

2:8 Jesus knew . . . what they were thinking. God sometimes revealed secrets about others to prophets (e.g., 2Ki 5:26; 6:12).

2:10 Son of Man has authority. Echoes Da 7:13–14, hinting at Jesus’ special identity.

2:14 tax collector’s booth. Most people in the Roman Empire did not like tax collectors; Jewish people viewed them as traitors. For assessment purposes, tax collectors were allowed to search anything except the person of a Roman lady; any property not properly declared was subject to seizure. In Egypt, tax collectors were sometimes so brutal that they were known to beat up aged women in an attempt to learn where their tax-owing relatives were hiding. Ancient documents reveal that when harvests were bad, on occasion an entire village, hearing that a tax collector was coming, would leave town and start a village somewhere else. People sometimes paid tax collectors bribes to prevent even higher fees being extorted. Some scholars consider Levi a customs officer who would charge tariffs on goods passing through Capernaum. Such tariffs were small by themselves (often less than 3 percent) but drove up the cost of goods because they were multiplied by all the borders they passed through. Customs officers could search possessions; customs income normally went to local governments run by elites who were cooperative with Rome. Others regard Levi as collecting taxes from local residents, likely working especially for agents of Galilee’s ruler, Herod Antipas.

2:16 teachers of the law who were Pharisees. Because Pharisees were known to be meticulous in interpreting the law, it was natural that some teachers of the law were Pharisees. Later rabbis sometimes contrasted Pharisees, as the godliest Judeans one would normally meet, with tax collectors, as the most ungodly one would normally meet. eat with tax collectors. Pharisees were careful about eating habits (e.g., all food must first be tithed) and valued religiously edifying conversation. More generally, people viewed table fellowship as establishing a covenant of friendship (indeed, in one ancient story, two warriors stopped fighting each other when they discovered that their fathers had shared a meal!). By eating with sinners Jesus thus appears to endorse them. Scripture warned against spending time with the ungodly lest one be influenced by them (Ps 1:1; 119:63; Pr 13:20; 14:7; 28:7), but Jesus is influencing them rather than the reverse.

2:17 healthy . . . sick. See note on Mt 9:12.

2:18 People in antiquity often held teachers responsible for the behavior of their disciples. fasting. Jewish tradition had added various fasts to Scripture, and fasting was a common expression of piety, including among Pharisees (see note on Lk 18:12).

2:19 guests of the bridegroom fast. Fasting was often linked with mourning, whereas weddings were considered a time for rejoicing. Many rabbis taught that weddings took priority over many religious obligations. To fast during a wedding would be to reject hospitality and fail to participate in the festivities, and so would prove offensive to the host.

2:22 wineskins. Ancient people used animal skins, most often goatskins, as containers for fluids. Wine expands as it ferments, so fermenting wine would have already expanded old wineskins to their limit. Filling these older, stiffer containers with still-expanding new wine would rupture them. Jesus’ new order demanded a new approach.

2:23 pick some heads of grain. Israelite law permitted those who were hungry to pick heads of grain when passing through a field (Dt 23:25; Ru 2:2). The complication here, in the eyes of their detractors, is doing so on the Sabbath (Ex 34:21; cf. reaping in the Mishnah in Shabbat 7:2).

2:24 Pharisees. See note on Mt 12:2. Pharisees followed their traditions carefully, but even Pharisees did not always agree among themselves on which actions violated the Sabbath. Like Jesus (vv. 25–26), they cited Scripture to support their various positions.

2:25 Have you never read . . . ? This question would insult Pharisees, who were reputed to be meticulous in the law. See note on Mt 12:4.

2:26 Abiathar the high priest. Ahimelek, not his son Abiathar, was the chief priest at the exact time described. By the first century, the title “high priest” (though normally in the plural) applied to anyone in the high-priestly families, both in the NT and Josephus (e.g., Antiquities 20.6, 180–181; Wars 4.160, 238); Mark identifies the era by the better-known son. Nevertheless, Matthew and Luke are clearer and more precise by omitting the reference to Abiathar.

2:27 Some other Jewish sayings followed this sort of reasoning (2 Maccabees 5:19; 2 Baruch 14:18).

2:28 Son of Man. Because Son of Man also means “human being,” Jesus’ hearers on this occasion could construe him as saying (in light of v. 27) that human needs take precedence over the Sabbath. The context of Jesus’ ministry, however, suggest that he is making a much more dramatic claim (see note on v. 10).

3:2 heal him on the Sabbath. See note on Mt 12:10.

3:5 hand was completely restored. For healing a withered hand, cf. 1Ki 13:6. Technically Jesus does not apply medical treatment or even lay hands on the man; no one considered a command to stretch out one’s hand as work!

3:6 began to plot with the Herodians. These Pharisees are inconsistent with usual Pharisaic traditions. See note on Mt 12:14. Many Pharisees were nationalists; Herodians supported the Herodian family, who worked for Rome. Pharisees worked together with Herodians only in the most urgent circumstances.

3:8 Idumea. The area of Edom, forcibly converted to Judaism starting in 129 BC; Herod the Great had been from there. regions across the Jordan. To the east; included Perea, one of Herod Antipas’s territories. Tyre and Sidon. Phoenician cities to the north, although some Jews lived there.

3:14 twelve. The sacred number of Israel’s tribes; those who saw themselves as a remnant of or renewal movement within Israel could symbolize this by choosing 12 leaders (cf. 1QS 8.1–2 in the Dead Sea Scrolls).

3:16 Simon . . . Peter. The Greek name Simon, which resembles the name of the Biblical patriarch Simeon, was one of the most popular Jewish male names of the period (perhaps the most popular). A special epithet or nickname would thus be helpful to distinguish different Simons (cf. v. 18). Nicknames were common; “Peter” means “rock.”

3:17 James . . . John. Common Jewish names in the period (James means lit. “Jacob”).

3:18 Andrew. A rare name. Philip. A common enough Greek name, sometimes used by Jewish people, including in Israel. Matthew. A somewhat common Jewish name. Zealot. Can mean simply someone noted for zeal, but at least in the next generation the title came to apply to those who expressed their zeal by fighting foreign oppressors and those viewed as collaborating with them.

3:19 Judas Iscariot. Although the meaning is uncertain, “Iscariot” may have meant, “man from Kerioth” (see Jos 15:25; cf. Jn 6:71).

3:21 family . . . went to take charge of him. Relatives (cf. v. 31) usually tried to hide the behavior of family members that could bring shame on the family.

3:22 possessed. Some in antiquity associated insanity (v. 21) with demonization. Some also thought that false teachers could speak by demons. If this association is at all in view here, it suggests a serious charge, since the penalty for leading God’s people astray was death (Dt 13:5; 18:20). Beelzebul. Probably a corruption of the name of the pagan deity Baalzebub (2Ki 1:2–3; see note on Mt 10:25).

3:27 tying him up. Magicians sought to “bind” spirits to secure their service, but Jesus is not invoking magic. Rather he’s offering a parable that shows his opposition to Satan. Delivering the strong man’s (the devil’s) possessions from his grasp alludes to God’s promise in Isa 49:25: God would defend and deliver his people from the powerful one.

3:29 whoever blasphemes against the Holy Spirit. One may “blaspheme” the Spirit because the Spirit is divine (most Jewish people recognized that the Spirit was divine, though they did not identify him as a separate person within the Godhead, as some NT passages do). Attributing the Holy Spirit’s work to an impure spirit (v. 30) is roughly tantamount to calling God Satan. Resorting to this tactic to deny the Spirit’s clear evidence about Jesus’ identity reflects impenetrable intransigence against truth, making repentance unlikely. One who genuinely repents has presumably not gone so far. guilty of an eternal sin. Biblical law provided atonement for most sins, but not for deliberate sins (Nu 15:30–31; Dt 29:18–20).

3:33 my mother and my brothers. Figurative kinship language was common in antiquity; e.g., one could call a respected older woman “mother” and call comrades or fellow members of one’s ethnic group “brothers.” Nevertheless, refusal to give higher priority to one’s physical family would appear offensive in ancient Mediterranean culture.

4:1 teach by the lake. One’s voice can carry to a crowd better if one is some distance away rather than surrounded by people on the same level. Some locations such as a cove near Capernaum also are thought to provide natural amplification for sound.

4:2 See the article “Parables.”

4:4 some fell along the path. See note on Mt 13:4.

4:5 rocky places. See note on Mt 13:5.

4:7 thorns. The plant described here is possibly a variety of thistle that commonly thrives around roads. It can grow to a height of more than three feet (a meter) by the month of April in the Holy Land.

4:8 some multiplying thirty, some sixty, some a hundred times. See note on Mt 13:8.

4:9 Whoever has ears. This is the language of riddles, inviting the wise to consider the meaning. Israel was not always ready to hear (Isa 6:10; Jer 6:10; Eze 12:2).

4:10 the Twelve. In antiquity, groups were sometimes named after their original number and could retain that title as a group. asked him. See note on Mt 13:10.

4:11 The secret of the kingdom. A special revelation about God’s promised kingdom, not information that would never be known; see Da 2:28–30, 44. (“Secret” or “mystery” as divine information now being divinely revealed also appears often in the Dead Sea Scrolls.) given to you. Some sages made some special information available only to their closest disciples, not considering outsiders ready for it. (This was true even of some later rabbis, who felt that teachings about creation or Ezekiel’s vision of God on his throne-chariot were dangerous if revealed to the unprepared.) Here the secrets go to those who “accept” it (v. 20)—i.e., the true disciples who remained after the crowds had gone, and thus received the interpretation from Jesus.

4:12 Rabbis who used parables in their teaching frequently related them to Scripture. Many OT passages speak of similar hardness of heart (e.g., Dt 29:4; Isa 42:19–20; 43:8; 44:18; Jer 5:21; Eze 12:2), but Jesus condenses a text in Isaiah in this parable. In Isaiah 6:9–10, God calls Isaiah to reveal truth to Israel that Israel will not receive, until the impending judgment (Isa 6:11). Their spiritual blindness increased as punishment for their refusal to heed what they had already heard from God (Isa 29:9–10).

4:13 Don’t you understand . . . ? See note on Mt 13:18.

4:14 the word. Ancient Jewish sources occasionally compared God’s word, the law, to seed (cf. 4 Ezra 3:20; 9:31–32); Jesus refers here to the message about the kingdom (v. 11).

4:17 quickly fall away. Jewish people viewed apostasy as a terrible sin.

4:21 lamp . . . under a bowl. The most common oil lamps of this period were small enough to hold in the hand; placing such a lamp under a container would obscure and likely extinguish it.

4:24 measure you use. Jesus uses the language of the marketplace, where grain or other substances would be weighed out for a certain amount of money, and would need to be weighed out fairly. Some Jewish texts apply the image to God’s justice at the last judgment.

4:30 What shall we say . . . ? Rabbis would often introduce parables in language like this.

4:31–32 mustard seed . . . birds can perch. Scholars do not all agree regarding which plant Jesus has in mind. The majority view would treat Jesus’ words here as hyperbole: a tiny seed (though not literally the tiniest) yields a large perennial shrub, growing anew every spring. The shrub can often reach a height of five feet (one and a half meters) and sometimes even ten feet (three meters). If this is the plant in question, birds could normally only perch in its branches (not “nest,” as the Greek term is sometimes translated). The quoted language evokes something more than a literal mustard bush: it borrows for God’s kingdom the image of a great kingdom of old that would be supplanted by God’s kingdom (Da 4:12). The glorious future kingdom was already active in a hidden way in Jesus’ ministry.

4:33–34 See notes on vv. 10–11.

4:37 boat. Galilean fishing boats were usually fairly small; the surviving example is 27 feet (8.2 meters) long, 7.5 feet (2.3 meters) wide and possibly 4.3 feet (1.3 meters) deep. Such a boat was built especially of cedar planks (but supplemented with other wood, even scrap wood) with joints and nails. In addition to a mast, it had four places spread out for rowers. Rental contracts stipulated that boats were to be returned unharmed barring an act of God, such as a storm. The shape of the hills surrounding the Sea of Galilee can funnel storms onto the water; they can be sudden and devastating to small boats out in the midst of the lake.

4:38 stern, sleeping on a cushion. The stern was probably elevated, and thus would fill with water less quickly. If any comparison is intended with Jonah, who had to be awakened on a boat during a storm, their behavior is a contrast (cf. Jnh 1:5–6, 12). Sleeping in security may fit faith (Ps 4:8); Greeks also respected sages who remained calm during storms.

4:41 the wind and the waves obey him. Jewish people understood that God controls the wind and waves (Ps 65:7; 89:9; 107:29); they did not expect it of a human being.

5:1 region of the Gerasenes. The Decapolis, a group of Hellenistic cities in Syria near Galilee, included such towns as Gadara (Mt 8:28) and Gerasa, Hippos and Pella. The population of the region was predominantly Gentile (cf. v. 11). Gerasa was much farther from the lake than Matthew’s Gadara, but larger and thus better known to Mark’s hearers (Jews and Gentiles outside the holy land and Syria). A region could be named by a town in its vicinity, even a town that is farther from the site. Some suggest instead the site of Gergesa (modern Kursi), which has a cliff and tombs in the area.

5:3 lived in the tombs. Jewish people regarded tombs and anything associated with the dead as impure; some associated spirits with such sites. no one could bind him. Superhuman strength appears in some reports of spirit possession in various cultures, occasionally even to the point of breaking restraints, as in this case. By contrast, Jesus can in some sense bind the strong man (cf. 3:27).

5:5 cut himself with stones. Observers in various cultures report that some of the spirit-possessed try to harm themselves or others, although in some cases they also seem immune to pain. Some participants in pagan cults were known to cut themselves as masochistic offerings to their gods (including in 1Ki 18:28), a practice that Israel’s benevolent God forbade (Dt 14:1).

5:7 What do you want with me . . . ? See note on 1:24. Most High God. See note on Ac 16:17. In God’s name. The Greek term normally means to put one under oath. This language appeared sometimes in magical exorcisms or often in other magical invocations of spirits; if the demons are trying to use defensive magic against Jesus, however, they are unsuccessful.

5:9 What is your name? Magicians often tried to control a spirit by using its name. If the spirits attempted to magically control Jesus in v. 7, they failed; here Jesus demands their name. Legion. On paper, a Roman legion had a strength of 6,000 (though usually a fighting force of closer to 5,000). A legion included ten cohorts, each with six centuries, but the demons are probably simply indicating that they are many (cf. the many pigs in v. 13).

5:10 out of the area. Just as soldiers got attached to regions, so observers report that in some places spirits claim to be attached to locales or local cultures. Some Jewish people (as evidenced in 1 Enoch) also recognized that demons could at most plead when confronted with God’s power.

5:11 herd of pigs. Jewish people considered pigs unclean (Lev 11:7–8).

5:13 into the lake. Mark does not clarify the spirits’ fate, but presumably they were at least somehow immobilized. drowned. Pigs may swim, but not indefinitely, probably especially after plunging over a steep bank. In some Jewish traditions demons could be destroyed (e.g., Abot de Rabbi Nathan 37A) or could be bound in an abyss (1 Enoch 88:1–3) or under the earth (Jubilees 5:6; 1 Enoch 10:12; 14:5) or bodies of water (Testament of Solomon 5:11; 25:7).

5:14 Those tending the pigs. Pigs require little oversight, but even if the herders were few, they were responsible to the owners (whether individuals or the town) for the pigs’ welfare.

5:17 plead with Jesus to leave their region. Unfamiliar with the Jewish tradition of Biblical prophets, Gentiles may have thought of Jesus as a dangerous magician, the sort of person that Gentiles associated with supernaturally harming others or public interests.

5:20 the Decapolis. See note on v. 1. Although some Jewish people lived there, the region was predominantly Gentile.

5:22 synagogue leaders. The Greek term could refer to different roles in different synagogues; sometimes it referred even to donors. It virtually always implied persons of status and usually wealth, however; Jairus undoubtedly was prominent in the community. fell at his feet. Falling on one’s face was an expected way to honor a ruler in Persia, but Greeks and Jews were often reluctant to do so because it could be construed as worship. Nevertheless, people often fell at others’ feet to plead for mercy or some great need.

5:23 put your hands on her. See note on 10:13.

5:25 subject to bleeding for twelve years. Under Jewish law, vaginal bleeding made a woman unclean (Lev 15:20–27, especially vv. 25–27). Because intercourse was forbidden in this condition, and because Jewish Pharisaic tradition commonly encouraged divorce if a couple of childbearing age could not produce offspring, her condition probably had either prevented her marriage or ended it. Jewish women often married soon after puberty.

5:26 care of many doctors. Although some legitimate biological and herbal knowledge existed, in many schools of medical thought it was mixed with inaccurate folk tradition. No universal certification existed for doctors in antiquity. Ancient medical techniques included bleeding a person.

5:27 came up behind him in the crowd. Coming up to Jesus in the pressing crowd would bring her into inadvertent physical contact with many people, making them unclean without their knowledge. touched his cloak. Even touching someone’s clothes—as she does with Jesus—rendered the wearer ritually impure (Lev 15:26–27). Here the effect is opposite: she is cleansed. Despite the expectation that Jesus would be viewed as being rendered unclean, he makes her act known (vv. 30–34); Jesus was willing to be identified with our uncleanness to make us whole.

5:38 people crying and wailing loudly. As soon as a person’s death was announced, professional mourners would gather to help facilitate the family’s and community’s grief. Later Jewish tradition specified a minimum of two mourners as necessary for even the poorest deceased person.

5:39 asleep. “Sleep” was a frequent metaphor for death throughout the ancient Mediterranean world, but the mourners, who were frequently around death, would know that she was not merely asleep.

5:41 took her by the hand. Contact with a bleeding person (vv. 28–34) could render a person impure until evening (Lev 15:21–23, 27), but touching a corpse rendered one impure for a week (Nu 19:14, 16). Talitha koum! Jesus addresses her in Aramaic, the mother tongue of most Galileans.

5:42 twelve years old. At this age, she had probably entered puberty and was close to the ordinary minimum age for a girl’s marriage in Jewish custom. Tomb inscriptions often lament those who died too young for marriage, but there is no need for further lamentation here.

6:3 carpenter. See note on Mt 13:55. Mary’s son. See note on Mt 13:55.

6:4 People normally expected support from their relatives and from fellow citizens from one’s home area. Prophets, however, often faced rejection and persecution (e.g., Jer 26:20), even in their own communities (cf. Jer 1:1; 11:21).

6:7 two by two. In antiquity, heralds or messengers most often traveled in pairs (valuable for a message’s witnesses; cf. the minimum number of witnesses in Dt 17:6; 19:15). No less important, traveling together provided greater safety.

6:8 staff. Travelers used a staff for protection against robbers, snakes and other creatures, and sometimes for maintaining one’s balance while walking on uneven mountain paths. no bag. In the Gentile world, wandering Cynic philosophers, known for living simply on city streets, carried a bag for begging, which is prohibited here.

6:9 sandals. Judean sandals had light straps running from between the toes to just above the ankle; unlike shoes, such sandals protected only the bottom of the foot. extra shirt. In the poorest areas, many peasants had only a single cloak. Biblical prophets also had to live simply in times of widespread apostasy, not dependent on decadent society (cf., e.g., 1:4; 1Ki 17:2–16; 18:13; 2Ki 4:38; 5:15–19, 26; 6:1).

6:10 Hospitality was one of the chief virtues in Mediterranean antiquity, and Jewish travelers could normally count on Jewish hospitality even in Diaspora cities.

6:11 shake the dust off your feet. Proper hospitality included offering water for guests to wash their feet; here the travelers’ feet remain conspicuously unwashed. Jewish people sometimes shook profane dust from their feet when entering a more holy place (cf. Ex 3:5); some did so when leaving pagan territory to enter the Holy Land. Cf. notes on Ac 18:6; 22:23.

6:13 anointed many sick people. People anointed themselves in connection with washing, but a more particular sort of anointing is in view here. Many people in antiquity believed that olive oil had medicinal properties (e.g., Josephus, Antiquities 17.172; Wars 1.657); Jewish people regularly used it on sores and wounds (cf., e.g., Isa 1:6; Lk 10:34), and some anointed people for healing for a range of maladies. Anointing was also employed for consecration, however (e.g., Ex 30:30; 40:13, 15; 1Sa 10:1). Because of this range of associations, oil provided an obvious symbol for healing.

6:14 King Herod. This member of the Herod family is Herod Antipas, son of Herod the Great (Mt 2:1) by a Samaritan wife named Malthace, and full brother of Archelaus (Josephus, Wars 1.562; cf. Mt 2:22). Technically, Herod Antipas was not a “king,” but a tetrarch (Mt 14:1; Lk 3:1, 19; 9:7)—governor of a territory (in his case, Galilee and Perea). He was from a royal family and many Galileans probably experienced him as if he were a king locally, but ultimately his desire for the title king cost him his authority altogether (see note on v. 17). raised from the dead. The sort of resurrection rumored here is like the raisings by prophets (1Ki 17:19–24; 2Ki 4:32–37), not a permanent raising to eternal life.

6:15 Elijah. People expected Elijah to prepare the way for the end (Mal 4:5–6). Some Jewish people, especially among those who were aristocrats, believed that prophets in the ancient sense had ceased, though many other Jews did follow the promises of those who acted like end-time prophets.

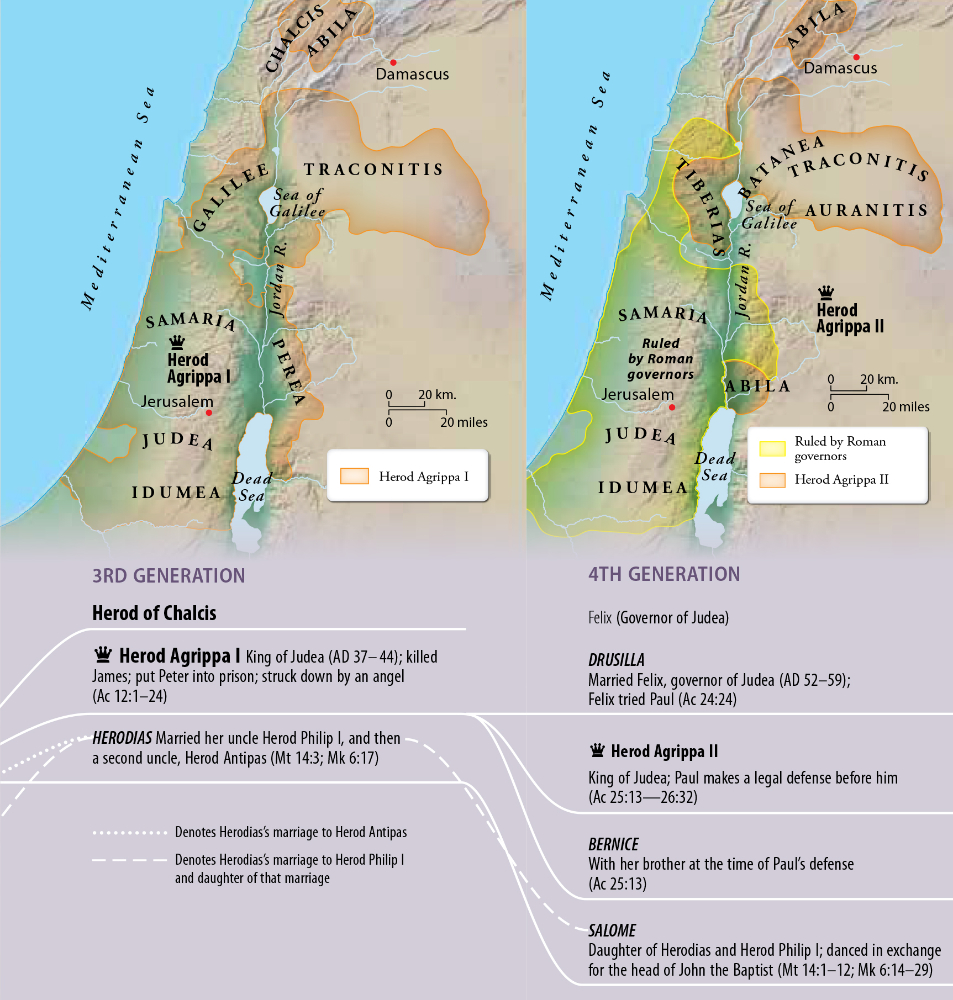

6:17 because of Herodias. For political reasons, Antipas had married the daughter of the powerful Nabatean king Aretas IV (mentioned in 2Co 11:32). Herod Antipas tried to win Herodias, though she was married to Antipas’s half brother Philip. When he wanted to marry Herodias, his brother’s wife, however, Herodias insisted that she would not marry a polygamist, so Antipas determined to divorce the Nabatean princess. She fled to her father, and the resulting feud stirred political trouble for Antipas; many of his Perean subjects were ethnically Nabatean, with loyalties to their people. Eventually, after the events narrated here, Aretas IV vanquished Herod Antipas in battle, and Antipas’s own people attributed his loss to divine judgment for Herod’s wicked execution of John the Baptist. John’s criticisms of Antipas’s behavior were moral (Lev 18:16; 20:21), but because they were politically sensitive Antipas kept John in prison. Josephus (Antiquities 18.119) says that Antipas imprisoned him in his Perean fortress Machaerus, which included a dungeon. (Perea was a region across the Jordan; John’s ministry had likely been active in this area.)

Ultimately, long after John’s execution, Antipas’s marriage to Herodias cost him his kingdom, but for different reasons. Josephus reports that Herodias was jealous that her brother, Agrippa I, became “king” of Judea (AD 41–44) whereas her new husband, Antipas, had remained merely a tetrarch since his father’s death in 4 BC, nearly three decades earlier. Thus she insisted that Antipas petition the emperor for the same privileged title; when Antipas finally complied, he was banished to Gaul, where he and Herodias spent the rest of their days without a kingdom (Josephus, Antiquities 18.240–255).

6:18 not lawful. Prophets often called God’s people back to God’s law, in this case Lev 18:16; 20:21.

6:19 wanted to kill him. Herodias’s behavior here fits the depiction of her character by the Jewish historian Josephus (see note on v. 17).

6:20 liked to listen to him. Aristocrats often liked to listen to philosophers and other speakers; Antipas showed interest in prophets (cf. Lk 23:8–9).

6:21 birthday. See note on Mt 14:6.

6:22 daughter of Herodias . . . danced. Herodias’s daughter Salome was probably between 12 to 14 years old, and perhaps already betrothed or married to Philip the tetrarch, when she was called on to dance. These parties often featured sensuous dancing, but typically members of the royal family were not called on to participate. The Herodian family, however, was known for such excesses.

6:23 oath. See note on Mt 14:7. up to half my kingdom. Herod’s promise evokes the promise made to Esther (Est 5:3, 6; 7:2), but Esther interceded for life whereas here Salome will request a prophet’s death. That Antipas is intoxicated seems clear here: as a tetrarch under Rome, Antipas lacked authority to give away any of his kingdom!

6:24 went out. Archaeologists note that the fortress Machaerus had two banquet halls; as in Greek banquets, the men and women dined separately. Thus Salome “went out.” Her mother Herodias was therefore also not present to witness her husband’s behavior.

6:25 head of John the Baptist. On some other occasions ancient sources report powerful authorities gruesomely executing persons (usually prisoners) at banquets as a favor to someone attractive. Ancients who read these reports normally regarded the person who granted the execution as wicked and disgusting.

6:26 because of his oaths and his dinner guests. The ancient Mediterranean world deeply valued honor and abhorred shame; Antipas’s public honor was at stake (see note on v. 23).

6:27 beheaded John in the prison. Because it was quick, beheading was considered the most merciful form of execution (though vv. 24–25 show that other considerations prevail here).

6:29 John’s disciples . . . took his body. Sons or other next of kin would normally take responsibility for a body’s burial; lacking these, a teacher’s disciples could perform this filial sort of obligation. laid it in a tomb. On burial customs, and the reticence of some to grant burial to their executed enemies, see notes on Mt 27:58–60.

6:34 sheep without a shepherd. Scripture spoke of God’s people without a leader as sheep without a shepherd (Nu 27:17; 1Ki 22:17; 2Ch 18:16; Zec 10:2; for others, cf. Isa 13:14). In such a setting, God himself might become their shepherd (Eze 34:8–16).

6:35–44 Ancient speakers and writers liked to contrast characters. Jesus’ benevolent banquet here contrasts with Herod’s drunken, lustful, murderous banquet in the preceding narrative.

6:35 late in the day. An evening meal often began shortly before (or sometimes after) sundown; although not feasible here, people would normally want to be safely home before sundown.

6:36 villages. Fewer than 3,000 would live even in the largest villages; most villages had only hundreds. buy themselves something to eat. Village markets would include bread and, around the lake, fish, although most such selling would occur before sundown. The villages in this region probably could not feed the entire crowd (see v. 44), but the disciples would at least be free from responsibility. A host should feed even the most unannounced of guests, but these were hardly normal circumstances.

6:38 loaves . . . fish. Bread was the most basic staple in the ancient Mediterranean world, but people also often ate fish, especially in fishing areas such as around the Sea of Galilee.

6:39 green grass. That the grass is green suggests it is springtime (Jn 6:4).

6:41 looking up to heaven. A familiar gesture for prayer, both among Jews (e.g., Ps 123:1; 1 Esdras 4:58) and Gentiles. gave thanks and broke the loaves. By this period it was a Jewish custom to thank God before one’s meal; then one would divide and distribute it. The later blessing, probably already sometimes in use, included: “Blessed are you . . . who bring forth bread from the earth.” (At some point it also became a custom to thank God after meals.) Multiplying food evokes Moses (the manna) and especially Elijah (1Ki 17:13–16) and Elisha (2Ki 4:3–7, 42–44).

6:43 twelve basketfuls. Polite hosts with means served enough food for some to be left over. Nevertheless, most people disapproved of wasting resources.

6:44 five thousand. Many today estimate Capernaum’s population between 600 and 1,500; some estimate Sepphoris’s population at only 15,000, though it was one of Galilee’s two largest cities. Even if these estimates were to prove low, a crowd of 5,000 (not including women and children, Mt 14:21) represents more people than most towns contained. The crowd’s size indicates that Jesus was now one of the most popular figures in Galilee.

6:45 Bethsaida. Also known as Julias, especially after AD 30, but the Gospels, which preserve early tradition, prefer its traditional local name.

6:47 middle of the lake. The lake is not large (13 miles [21 kilometers] long by 8 miles [13 kilometers] wide at its widest point), and the disciples were probably crossing at a much narrower point. Nevertheless, progress was delayed by contrary winds (v. 48).

6:48 about to pass by. This phrase could evoke God’s activity in Ex 33:22; 34:6 and applies to God also in Job 9:11, one of the same passages that refers to God treading on the sea (Job 9:8; God treads on the sea also in Ps 77:19; Hab 3:15). Together with Jesus’ “I am” statement (see v. 50; translated “It is I”) the narrative leaves no doubt as to Jesus’ divine identity (see note on v. 50).

6:49 ghost. Despite widespread Jewish teachings about heaven and the future resurrection, on a popular level many people believed in ghosts and certainly spirits more generally. Some people in antiquity believed that the souls of those who died unburied at sea wandered near the site of their demise.

6:50 It is I. The NIV’s translation is legitimate and fits the context, but the words in Greek here also mean “I am,” evoking Ex 3:14 and (especially in the Greek version) Isa 41:4; 43:10; 48:12; 51:12. Together with the context of Jesus treading on waters and being “about to pass by” (v. 48), this experience reveals Jesus’ deity (see note on v. 48).

6:53 Gennesaret. Refers either to a plain (over three miles [five kilometers] long by over one mile [one and a half kilometers] wide) on the northwest of the lake, between Capernaum and Tiberias, or to a town on the site of ancient Kinnereth (Jos 19:35). Jesus probably ministered often in this densely populated and prosperous region.

6:55 mats. Would be readily available; for the poor, mats could be their only beds.

7:1 teachers of the law. Although the Greek term translated here can mean “scribes,” and many ancient villages had scribes who could write legal documents, high-level Jewish scribes were probably teachers of the law. Most Pharisees and many teachers were apparently based in Jerusalem.

7:3 ceremonial washing. The Jewish custom of washing hands arose after the completion of the OT, probably in the Diaspora. Mark’s audience may only have known only the Diaspora practice, but the Pharisees, who were centered in Judea, were known to be particularly meticulous in this custom.

7:4 unless they wash. People could cleanse their hands to remove ritual impurity contracted in the public markets. They would pour water over the hands or immerse them as far as the wrist. washing of cups, pitchers and kettles. Pharisees developed elaborate rules for purifying vessels.

7:5 tradition of the elders. Pharisees were known for faithfully following their oral traditions. defiled hands. Public opinion judged teachers by their disciples’ behavior.

7:7 human rules. Isa 29:13 challenged reliance on rules made by men—a warning here used to challenge Pharisaic traditions (vv. 3–5).

7:10 Ancient Mediterranean cultures emphasized honoring and caring for parents; Pharisees valued this practice even more highly than most.

7:11 Jewish people could vow and dedicate property to the temple (corban means “consecrated to God”). One could thus render property forbidden for others’ use. Some exploited the loophole that this practice created; one could dedicate for sacred use what instead should be used to care for aged parents.

7:15–19 A few other rabbis eventually offered statements similar to Jesus’ in v. 15. They did so only privately to their disciples, however, since they still expected literal observance of the commandments. Even some Jews who interpreted the food laws allegorically (such as the Jewish philosopher Philo) objected when some others went so far as to reject literal observance. In v. 19 Mark construes Jesus as relaxing literal observance.

7:21–22 Ancient writers, both Jewish and Gentile, often listed vices.

7:24 Tyre. A major city in Syrian Phoenicia (v. 26). God answered Elijah’s prayer to heal a woman’s child in this region in 1Ki 17:9–24.

7:26 born in Syrian Phoenicia. This description distinguishes the original Phoenician homeland in Syria from Libophoenicia, the Phoenician settlements in North Africa. Since the time of Alexander, “Greeks” (including Macedonians) had constituted a ruling class of citizens; the republics of Tyre and Sidon now considered themselves Greek.

7:27 children’s bread. Citizens of Tyre and Sidon flourished in part at the expense of the countryside, whose resources they exploited, and also needed imports from Judea. Some scholars thus suggest that, in a sense, she belonged to a class that had been taking bread that Jews and Gentiles in the outlying region could have used to feed their children. Now she must humble herself in a different situation. Most important, Jesus emphasizes the priority of Israel; humbling herself to acknowledge this priority requires transcending ancient national rivalries. dogs. This term was a harsh insult for either gender, but it is not used as a direct label here. Nevertheless, Jews, unlike some Gentiles, did not keep dogs as pets and typically treated them as unclean, so it is not a complimentary image.

7:28 children’s crumbs. See note on Mt 15:27.

7:29–30 Those who persevered in insistent faith often experienced rewards (cf. such respectful insistence in, e.g., Ge 18:23–32; Ex 32:11–14; 1Ki 18:36–37; 2Ki 2:2, 4, 6, 9; 4:28).

7:31 Sidon. Like Tyre (see note on v. 24), Sidon was a major city of Phoenicia. Sidon is roughly 24 miles (39 kilometers) from Tyre, so probably required the minimum of a day’s travel on foot. It was known for pagan worship, but a Jewish community lived there. the Decapolis. See note on 5:1.

7:33 fingers into the man’s ears. Jesus might thoughtfully communicate his intentions to the man, who was brought by others, in a makeshift sign language. spit. Spittle was usually deemed unclean, but it was sometimes used in medicinal, magical, and religious cures.

7:34 Ephphatha! Mark retains Jesus’ expression in Aramaic, the dominant language in rural Galilee.

8:11 sign from heaven. Could mean simply one from God, or predicting a heavenly sign such as an eclipse or other phenomenon.

8:15 yeast. Known for spreading and pervading its sphere of influence. Pharisees . . . Herod. Pharisees and Herodians worked together only in exceptional circumstances (12:13; see note on 3:6), but they shared a common spiritual problem.

8:17 Do you still not see . . . ? On spiritual blindness, see note on 4:12.

8:22 Bethsaida. See note on 6:45.

8:23 spit on the man’s eyes. See note on 7:33.

8:27 Caesarea Philippi. A Gentile city at the northern boundary of ancient Israel, some 25 miles (40 kilometers) north of the Sea of Galilee. Its earlier name was Paneas, in honor of the pagan god Pan, and Herod the Great built a temple for worshiping Caesar here. Herod’s son Philip expanded the city and renamed it Caesarea in the emperor’s honor. Like most other cities, Caesarea Philippi depended in part on its many surrounding villages for produce.

8:28 others say Elijah. Many people expected Elijah’s return before the end (cf. Mal 4:5). This return was also predicted in Sirach and appears commonly in subsequent Jewish literature.

8:29 Messiah. Jewish people held a range of opinions about the Messiah, or “anointed one.” In general, however, most expected a coming king from the house of David (see, e.g., Isa 9:6–7; 11:1–5; Jer 23:5–6; Psalms of Solomon 17:21). To establish the Davidic kingdom in Israel such a ruler would need military power to overthrow the oppressive kingdom of Rome (for the expectation of oppressive kingdoms’ fall, cf. Da 2:44), and many expected such a ruler (cf. Psalms of Solomon 17). In this period they did not normally expect the Messiah to be martyred (v. 31).

8:30 Some evidence suggests that Messianic figures were not expected to accept the title until they succeeded in their mission. Certainly ancient culture frowned on boasting unjustifiably, though leaders were often ready for their followers to do so on their behalf. To accept the title, however, was to publicly (and in this case prematurely) challenge Rome, for even a ruler such as Herod Antipas could not acquire the title of “king” without the emperor’s approval. not to tell. Some commands to silence (e.g., 1:44; 5:43) may have been to reduce the heavy crowds Jesus faced (2:2; 3:7–10), but a direct Messianic claim would bring Jesus into conflict with the authorities even faster than his growing following would. It was not yet the appropriate time (cf. 12:6–8; 14:61–62).

8:31 must suffer. Although perhaps as early as the second century some sources spoke of a suffering Messiah (Messiah ben Joseph), there is no evidence for such a concept in this period (see note on v. 29). Jesus’ disciples expected to follow him to the kingdom—not to martyrdom. the elders, the chief priests and the teachers of the law. Presumably these together represent members of the Sanhedrin—the municipal senate of Jerusalem. These were aristocrats who in some ways had more in common with Greek or Roman aristocrats than with Galilean peasants or artisans such as Jesus and his followers.

8:32 Peter . . . began to rebuke him. Although Peter may have meant well, openly challenging one’s teacher was a serious breach of protocol.

8:33 Jesus turned. Disciples were expected to walk behind their teachers. he rebuked Peter. Given standard expectations, followers of a Messiah expected to triumph rather than face martyrdom (vv. 34–38).

8:34 take up their cross. See note on Mt 16:24.

8:35 to save their life will lose it. See note on Mt 16:25–26.

8:38 the Son of Man . . . comes in his Father’s glory with the holy angels. Most Jewish people in the Holy Land expected a future day of judgment. Scripture had promised that God would come with his holy ones (Zec 14:5); here Jesus fills this divine role. He alludes also to the coming Son of man in Da 7:13, at the time that he would receive the kingdom.

9:1 Jewish people believed that God reigned in the present but looked for his kingdom, or reign, in a special way in the world to come. Although Jesus speaks in this context about the ultimate future (8:38), here he probably predicts an event that would foreshadow that future (v. 2).

9:2 transfigured. Although ancient literature, including Jewish literature, had various stories of people or other beings who were transformed or transfigured with light, the most widely known, pre-Jesus transfiguration story for early Christians was the story of Moses. Exposed to God’s glory on Mount Sinai, Moses reflected that glory (Ex 34:29–35); Jesus probably also waits six days here in order to evoke Ex 24:16. Yet Jesus is greater here than Moses (vv. 4–7).

9:3 bleach. Refers to one of the activities of cloth refiners, who used chemicals to bleach white cloth and tried to remove stains. Jewish sources often depicted heavenly beings in gleaming white.

9:4 Elijah and Moses. Elijah was taken to heaven alive (2Ki 2:11); God buried Moses (Dt 34:6), although some Jewish traditions nevertheless said that he was also preserved alive. Jewish people expected the return of Elijah (Mal 4:5–6) and the coming of a prophet like Moses (Dt 18:15–18).

9:7 cloud appeared and covered them. The cloud of God’s glory overshadowed Mount Sinai (Ex 24:15–16), from which also God spoke from heaven (Ex 20:22). voice. See note on 1:11. Jesus is exalted above Elijah and Moses here. Listen to him! Some scholars think this statement evokes the command regarding the prophet like Moses in Dt 18:15.

9:11 come first. Elijah would prepare the way for God’s coming (Mal 4:5–6; Sirach 48:10). Jesus applies the prophecy figuratively to John the Baptist (see notes on 1:2–3, 6).

9:14 arguing. If we may judge by the traditions of later rabbis, teachers of the law were skilled in argumentation.

9:22 thrown him into fire. Similar experiences are reported in various cultures: some people believed to be controlled by evil spirits inflict physical injury on themselves. Some others perform potentially painful or injurious activities without pain or injury. (But cf. note on Mt 17:15.)

9:25 deaf and mute spirit. Although various afflictions and problems could happen without being caused by spirits, spirits could also cause these.

9:26 convulsed him violently. Spirits often were believed to depart very demonstratively, as this one does.

9:28 asked him privately. Given the public emphasis on honor and shame in the wider culture, disciples would probably not want to draw further public attention to their failure to be able to carry on the activities that their teacher modeled for them. But they would view their teacher as a superior and could ask him privately.

9:32 afraid to ask him. In a society where honor was highly valued, people were often reluctant to admit ignorance. In this case, the disciples will also remember Jesus’ strong response to Peter’s resistance after a previous announcement of Jesus’ suffering (8:31–33).

9:34 argued about who was the greatest. Rivalry for greater honor was common among ancient Mediterranean men. This practice ranged from playful competition among friends to deadly competition among enemies; Jesus’ disciples here are not enemies, but it is probable that they have gone beyond playful banter.

9:35 Jesus’ instructions here run completely counter to antiquity’s normal public male culture of seeking honor.

9:36 little child. Somewhat in contrast to modern Western culture, where children are often objects of consumer marketing and the subjects of greater psychological and educational concern, children in Jesus’ culture were normally powerless, expected to be obedient and dependent. They were, however, usually objects of their parents’ love. in his arms. The culture was more tactile than the modern West, and non-family members holding children was safer and more common.

9:38 in your name. That the man would cast demons out in the name of Jesus rather than invoking a spirit or using stinky substances reveals his faith in Jesus (on ancient practices of casting out demons, see note on Mt 8:16). Some exorcists did try to drive out demons by invoking the name of Solomon, who was reputed to be a great exorcist (Josephus, Antiquities 8.47), but this man may act in Jesus’ name in a different way (cf. v. 37).

9:40 The idea that a person must choose one side or the other was widely circulated in antiquity and would have been familiar to Jesus’ disciples. At least in urban politics, networks of alliances typically meant that one was friends with a friend’s friends and enemies of a friend’s enemies, though such alliances could be adjusted when useful.

9:41 cup of water. The poorest person might have only water to offer, but hospitality obligations demanded sharing with a visitor what one had. not lose their reward. God would reward hospitable treatment of his prophets (e.g., 1Ki 17:12–16; 2Ki 4:8–17). Jewish people often spoke of reward in relation to the day of judgment.

9:42 to stumble. Jewish sources often used “stumble” figuratively for sin or apostasy (e.g., Eze 14:3, 7; Sirach 9:5). large millstone. See note on Mt 18:6.

9:43–47 cut it off . . . cut it off . . . pluck it out. Corporal punishment, the removal of a limb (e.g., Ex 21:24), was less serious than capital punishment; Jewish teachers often employed hyperbole, rhetorical overstatement to make a point. See note on Mt 5:30.

9:43, 45, 47 hell. Gehinnom (see note on Mt 3:12). Jewish thinkers sometimes expected God to raise the dead in the form in which they died before healing them (e.g., 2 Baruch 50:2–4).

9:48 Jesus uses the closing verse of Isaiah (Isa 66:24), where the corpses of those who defied God serve as a warning to others. The context is the time of the new creation and deliverance of God’s people (Isa 66:22–23).

9:49 salted with fire. Priests salted some sacrifices as well as cooked them (Lev 2:13; Eze 43:24). fire. Cf. perhaps v. 48.

9:50 Salt . . . loses its saltiness. Teachers sometimes spoke in riddles. Genuine salt could not lose its saltiness (though some impure salt deposits that Judeans knew could), but if (hypothetically) it did, it was worthless, as one later rabbi noted; one could not make it salty except by salting it (see note on Mt 5:13). Salt was sometimes used in covenants (e.g., Nu 18:19; 2Ch 13:5).

10:1 across the Jordan. The region of Perea.

10:2 divorce. In Jesus’ generation Pharisees were debating among themselves the proper grounds for divorce. See note on Mt 19:3.

10:4 The Pharisees cite the allowance of divorce in Dt 24:1–4.

10:5 because your hearts were hard. Ancient teachers of the law sometimes recognized that some of Moses’ laws were written as concessions to human weakness. Civil laws don’t necessarily represent God’s ideals; typically they merely place limits on human sin (see notes on Mt 5:22, 28). Thus, e.g., the Law of Moses forbade marrying a wife’s sister (Lev 18:18) but not polygamy per se; it limited the abuse of slaves (Ex 21:26–27) but did not outlaw slavery per se. Jesus appeals to a divine ethic more complete than Israel’s civil law.

10:6 Teachers sometimes challenged other teachers’ interpretations of verses (here some Pharisees’ understanding of Dt 24:1) by appealing to other texts that contradicted those interpretations. at the beginning. For many Jewish people, the ideals of the “beginning” foreshadowed the future kingdom. God paired the man and woman in Ge 1:27 so that husband and wife could reproduce (Ge 1:28). Others cited the passage for restoring divine ideals; e.g., the people who composed the Dead Sea Scrolls used Ge 1:27 (cited here) to prohibit kings marrying multiple wives.

10:8 one flesh. Continuing his reference to the Genesis creation narrative, Jesus cites Ge 2:24. In the OT, members of the same family unit were “one flesh,” so marriage created a new family unit.

10:10 the disciples asked. Teachers sometimes explained matters privately to their disciples.

10:11 Treating marriage as indissoluble leaves any remarriage adulterous; yet v. 9 prohibits divorce rather than treating it as impossible. Because Jesus often used graphic hyperbole (see note on Mt 5:30), offered general statements that might be qualified in some cases (see note on 1Co 7:15), and elsewhere treated the dissolution of marriage as possible (though wrong; Mk 10:9; Jn 4:18), a number of interpreters view the present statement as hyperbole. Hyperbole was meant to graphically reinforce the point, here the context’s warning against breaking one’s marriage.

10:12 if she divorces. Only men could divorce under the traditional practice in Israel and the custom recognized by the Pharisees (cf. v. 2). But women with means did sometimes divorce their husbands, as was more common in the Greek and Roman world (see notes on 1Co 7:10–11); e.g., Herodias (Mk 6:17) had divorced her husband to marry Antipas (Josephus, Antiquities 18.136, though noting his disapproval).

10:13 to place his hands on them. Laying hands on someone to bless them was an ancient, Biblical practice (Ge 48:9, 14). Like Elisha’s disciple Gehazi (2Ki 4:27), Jesus’ disciples try to protect him by keeping a suppliant away from him, and like Elisha, Jesus welcomes the petitioner.

10:14 kingdom . . . belongs to such as these. Some expected warriors to establish the kingdom; few associated it with children (though cf. Isa 11:8).

10:15 like a little child. Young children were dependent on their fathers (see note on Mt 6:8).

10:17 Good teacher. Praising or even flattering teachers was common. what must I do to inherit eternal life? Some Jewish people asked Jewish teachers how to have eternal life. inherit eternal life. A common expression; eternal life meant the life of the coming age. Jewish people envisioned this life in various ways, often as a restoration of paradise, as well as living together in peace, joy and justice.

10:18 Why . . . call me good? People often respected teachers who deflected praise; this was considered honorable behavior. In this case it may also challenge the inquirer’s self-certainty (v. 20).

10:20 since I was a boy. At least according to later Jewish tradition, a boy became fully responsible for the commandments at his coming-of-age to become a young man, around age 13.

10:21 sell everything . . . give to the poor. Although very few teachers made demands like the one Jesus makes here, on occasion some radical teachers weeded out uncommitted disciples with such demands. treasure in heaven. Jewish people sometimes spoke of heavenly rewards in this way. The brief allusions in the earliest sources usually do not specify what they meant by it, except that it means being rewarded in the coming world. follow me. Be his disciple; disciples followed behind their teachers.

10:23 the rich. Although some believed that the poor were especially godly, many believed the wealthy were specially blessed by God.

10:25 camel . . . needle. Camels were the largest animals in the Holy Land; the eye of a needle was proverbially small (it was a small opening at the top of a needle, then as now, not, as some have argued, a gate in Jerusalem). A camel getting through the eye of a needle was apparently a figure of speech for accomplishing what was impossible (like the analogous Babylonian Jewish figure of speech about an elephant getting through a needle’s eye). Jewish teachers often used hyperbole to emphasize their points.

10:30 a hundred times as much in this present age . . . and in the age to come. Jewish people expected reward in the world to come, in particular eternal life (see v. 17). Reaping a hundred times what one sowed was an extraordinary yield (Ge 26:12). The rewards in the present to which Jesus refers might be the benefits of believers being one family and sharing their means with those in need.

10:33 the chief priests and the teachers of the law. The powerful elite in Jerusalem; crossing them would make them mortal enemies, but the sort of Messiah (8:29) most people expected would have to deal with them somehow, whether by persuasion or by force. hand him over. Because only Rome exercised the right to execute people, hostile members of Jerusalem’s elite would have to hand Jesus over to the Roman governor.

10:34 flog him. Flogging was standard before execution; abuse of prisoners, including mocking, was common.

10:35–37 James and John expect Jesus to establish his kingdom, perhaps soon in Jerusalem (cf. v. 32). Loyal friends and followers who shared a future ruler’s dangers often earned the right to ask him special favors (cf. also expectations engendered by vv. 29–31). Seats beside a ruler were the highest in a kingdom.

10:38, 39 cup. See note on 14:36. baptism. Cf. Lk 12:49–50. James suffered martyrdom before any of the other members of the 12 did (Ac 12:2), but tradition claims that John outlived all the others.

10:42 Gentiles lord it over. Jesus accurately depicts the pursuit of power in the ancient Mediterranean world, from the emperor down. Jewish teachers usually used Gentiles as negative examples.

10:44 first must be slave of all. As in 9:35, Jesus’ teaching here violated expectations for honor in ancient society.

10:45 serve . . . give his life. The Son of Man was expected to reign (Da 7:13–14), but he came as a servant who would give his life for others (cf. the suffering servant of Isa 53:4, 11–12).

10:46 Jericho. About 12 miles (20 kilometers)—less than a day’s walk—from Jerusalem, although the journey would be uphill from here. In this period Jericho was wealthy, with residences of aristocratic priests and with winter palaces once held by Herod the Great; especially during this time of pilgrimage for the festival, a beggar on the roadside might acquire ample provision. The ruins of the original Jericho lay south of the current city; some scholars thus think that the Jericho mentioned here is a different site than the one in Lk 18:35. Bartimaeus. “Bar” (as here in Bartimaeus) is Aramaic for “son of.”

10:47 Son of David. Implies he believes Jesus is the Messianic king.

10:48 he shouted all the more. Refusing to be deterred expresses faith (cf., e.g., 2Ki 4:27–28).

11:1 Bethphage. An apparently walled suburb of Jerusalem, outside the capital’s city walls and about three quarters of a mile (one kilometer) east of the peak of Mount Olivet; it was probably closer to Jerusalem than Bethany, to its east. Bethany was some two miles (three kilometers) east of Jerusalem, on the eastern side of Mount Olivet.

11:2 no one has ever ridden. Animals never before ridden or yoked were often those preferred for dedication to God (Nu 19:2; Dt 21:3; 1Sa 6:7).

11:3 The Lord needs it. Roman soldiers could commandeer animals for their use; more to the point here, so could kings, such as the Lord.

11:7 colt. Although Mark does not specify Jesus’ allusion to Scripture, Jesus entering Jerusalem on a colt evokes Zec 9:9—the humble king.

11:8 spread their cloaks. Casting garments for a ruler to walk on was a way of hailing him king (2Ki 9:13). spread branches. People would also wave branches to celebrate triumphs (cf. 1 Maccabees 13:51; 2 Maccabees 10:7).

11:9–10 Pilgrims already present often welcomed the newcomers. The crowds would know Ps 118:25–26 by heart; cf. note on v. 9.

11:9 Hosanna. A request for salvation or deliverance, as in Ps 118:25. It was part of the Hallel, consisting of Ps 113–118, which was sung at the Passover season (see also Mt 26:30). Mark’s audience may not have known this detail, but it reflects accurately Jesus’ original setting. Hopes for a new act of redemption also ran high at Passover; the expectation of the Davidic kingdom here may be provoked by knowledge of Jesus’ proclamation of the kingdom and the way he was entering (see v. 7 and note).

11:11 went into the temple courts. The temple mount consumed more than a quarter of Jerusalem and constituted the focal point of activity for festal pilgrims, from early morning until late afternoon. (The temple’s “evening offering” was about 3:00 p.m.) Bethany. On the Mount of Olives, located two miles (three kilometers) to the east, within walking distance from Jerusalem (v. 1), but returning to that village before dark was important. Because Jerusalem was crowded for the festival, it made sense to find lodging outside the holy city until the Passover night itself; Jesus apparently lodged with Simon (14:3; cf. Jn 11:1).

11:13 fig tree in leaf. On the eastern side of the Mount of Olives, fig trees could already have leaves at Passover season (late March or early April). They did not yet, however, have ripe figs; they had only green early figs, which did not taste good. They could ripen in June, but often fell off beforehand, so that only leaves remained. If a tree had leaves but produced no early figs, it would remain fruitless that year. it was not the season for figs. Jesus would know this but may here be offering an acted parable like the prophets: his judgment against the fig tree (vv. 14, 19–20) frames his prophetic protest against the fruitless temple establishment (vv. 15–18).

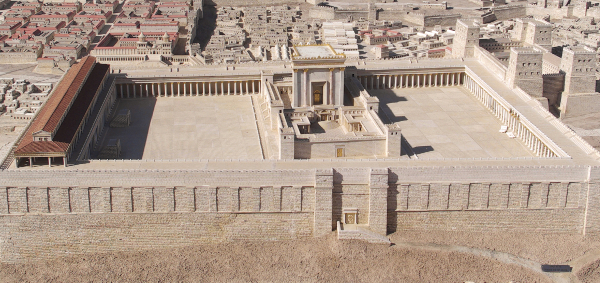

11:15 those who were buying and selling. Jerusalem needed markets and bazaars to supply the massive influx of pilgrims; although most of these may have been outside the temple there was little room immediately outside it, so sacred items (such as animals for sacrifice; cf. pigeons in Lev 1:14; 5:7; 12:8) would likely be purchased on site. (The temple mount offered Jerusalem’s largest space and could accommodate an estimated 75,000 people at one time.) money changers. Because each local region had its own currencies, moneychangers performed a service by changing local money into standardized currency so people could buy what they needed. Perhaps Jesus objects to the misplaced emphasis. But this site, the massive outer court, was also the only place of worship for the Gentiles (see note on v. 17).

11:16 temple courts. The OT temple segregated priests from people, but did not separate Gentiles from the people (1Ki 8:41–43). By contrast, for purity reasons, the current temple, constructed mostly under Herod the Great, divided the outer court into the court of Israel, for Jewish men; on a lower level outside of that the court of (Jewish) women; and on a lower level outside of that a third court that can be referred to as the court of the Gentiles. Posted signs warned that any Gentile going beyond the court of the Gentiles would be killed.

11:17 Isa 56:7 (quoted here) shows God’s ideal for the temple: Gentiles were to be welcome (Isa 56:3–6). This ideal may contrast with the current arrangement of the temple (see note on v. 16). den of robbers. Evokes Jer 7:11; in that context people believe that the temple will protect them from God’s judgment, but God warns that he will judge the temple (see 13:2).

11:18 began looking for a way to kill him. Any challenge to practices legally conducted in the temple constituted a challenge to the priestly authorities who controlled the temple. Unlike Pharisees, who earlier plotted against Jesus fruitlessly (3:6), the chief priests held significant political power and could swiftly deal with affronts to their honor.

11:19 out of the city. Because the festival had swelled Jerusalem’s population, it was easiest for those who knew people in the vicinity to find accommodation outside the city walls (vv. 11–12).

11:23 “Moving mountains” became a figure of speech for a task that was considered virtually impossible. Some scholars think that “this mountain” refers to the Mount of Olives, which at this point was within sight for the disciples (cf. Zec 14:4); others believe that the temple mount is in view (cf. Zec 4:6–9). Neither application would alter the principle here.

11:27 the chief priests, the teachers of the law and the elders. The three groups mentioned here are the most powerful elements of Judean society, the elite groups represented in the Sanhedrin. They recognized that Jesus’ actions challenged their authority (cf. v. 28).

11:29 Sages often met questions with counter-questions.

11:30 from heaven. Jews commonly used “heaven” as a circumlocution for “God” (e.g., Da 4:26; 1QM 12.5).

11:32 feared the people. Although the Pharisees were popular with the people, Jesus was more popular. The Sadducees, whose chief priests dominate the alliance against Jesus here (v. 27), held political power but were less popular with the people than were the Pharisees. They were responsible for the temple and could not afford unrest during the crowded conditions of the festival (14:2).

12:1 parables. Teaching in parables allows Jesus to speak truth in riddles (see the article “Parables”); the meaning is transparent (v. 12) but not directly indictable. wall . . . winepress . . . watchtower. See note on Mt 21:33–34. rented the vineyard to some farmers. Jesus draws the details here from the parable in Isa 5:1–2, in which the vineyard was Israel (5:7). The “tenants” here in vv. 1–9 must thus represent the temporary caretakers of Israel—the chief priests, the teachers of the law and the elders (v. 12; 11:27). Although many Galileans owned their own plots of land, many landless peasants found work on larger estates. Wealthy absentee landowners were common; they usually either contracted laborers or rented their land to tenant farmers (serfs).

12:2 some of the fruit. Tenant farmers lived and worked their estates and merely paid the landowners a portion of the harvest. Because tenants did not own the land they worked, they sometimes had to pay the landowners half the harvest. Profits from vineyards usually did not begin to be realized until four years after planting; the owner in this story is wealthy enough to be able to afford the delay. Contracts specified the tenants’ obligations; owners were advised not to be too lenient lest the tenants default on what they owed.

12:5 killed. See note on Mt 21:35.

12:6 son, whom he loved. See note on Mt 21:37.

12:7 inheritance will be ours. See note on Mt 21:38. To the people listening to Jesus’ story, this would make the behavior of the tenants appear even more deluded and ridiculous.

12:10–11 This passage (Ps 118:22–23) would resonate with Jesus’ hearers—it had been recently sung by these people as part of the Passover. It comes from the Hallel, which consists of Ps 113–118 (see notes on 11:9–10).

12:13 Pharisees and Herodians. Pharisees, some of whom supported older, nationalistic traditions, and Herodians, probably clients or political partisans of Herod Antipas, worked together only in exceptional circumstances—such as these.

12:14 Is it right to pay the imperial tax . . . ? They may expect the leader of a Messianic movement to oppose Roman taxes, like an earlier Galilean revolutionary movement; if Jesus speaks against such taxes, they have public witnesses for arresting him and handing him over to Pilate on the charge of treason (cf. Lk 23:2).

12:16 coin. See notes on Mt 22:19–20.

12:17 Give . . . to God what is God’s. See note on Mt 22:21.

12:18 Challenging teachers in public was common. Sadducees, who say there is no resurrection. See note on Mt 22:23.

12:19 a man’s brother. Because widows could be left destitute, the extended families into which they married were supposed to provide for them by a brother of the deceased marrying the widow (Dt 25:5–6).

12:20–22 See note on Lk 20:29–31.

12:23 At the resurrection. Sadducees were known to pose conundrums such as this to the Pharisees, seeking to illustrate what they believed were the absurd implications of belief in the resurrection.

12:24 you do not know the Scriptures. The highly educated and literate Sadducees would hear this statement as an insult. power of God. A common Jewish prayer associated God’s power with the resurrection of the righteous at the end of the age.

12:25 neither marry nor be given in marriage. Grooms married; fathers gave their daughters in marriage. like the angels. Most Jewish people agreed that angels, who are immortal, did not propagate; the same then would be true of those resurrected to immortality.

12:26 in the Book of Moses. See note on Mt 22:29. the God of Abraham, the God of Isaac, and the God of Jacob. See note on Mt 22:32.

12:28 Of all the commandments, which is the most important? This question was one of the issues commonly debated among Pharisaic teachers in the first century. Many, e.g., felt that the greatest was honoring one’s parents. Rabbi Akiba, a later rabbi, came closer to Jesus’ view here when he asserted that “Love your neighbor” is the greatest commandment.

12:29–30 Dt 6:4 (noted in v. 29) was the cornerstone of Jewish faith, the Shema. Jewish people regularly recited this passage (Dt 6:4–5).

12:31 Love your neighbor as yourself. See note on Mt 22:39.

12:32 Well said. This teacher of the law rightly recognizes Jesus’ words as consistent with Scripture; they were also compatible with Jewish tradition.

12:34 no one dared ask him any more questions. People often raised questions and objections to publicly challenge or even shame a teacher; the best speakers could silence and shame their opponents, because such teachers could make hostile questions themselves look foolish.

12:36 speaking by the Holy Spirit. In traditional Jewish parlance, this is another way of saying “speaking by divine inspiration.” See note on Mt 22:44. under your feet. In ancient artistic renderings, defeated enemies are often shown as being under their conqueror’s feet (cf. Jos 10:24).

12:38 be greeted. Social convention stipulated that social inferiors should greet superiors first; later rabbis believed that the superiors included rabbis. marketplaces. Because in villages and towns people congregated especially in marketplaces, this location would provide opportunity for many greetings.

12:39 most important seats in the synagogues and the places of honor at banquets. See note on Mt 23:6.