Annotations for 1 Corinthians

1:1 Paul . . . and our brother Sosthenes. Ancient writers rarely coauthored letters; sometimes letters that listed secondary authors merely were a special way of the second author sending greetings. Nevertheless, it is not impossible that Sosthenes contributed somehow to the letter. Scholars debate whether this is the Corinthian Sosthenes of Ac 18:17, now (or perhaps even then) a believer.

1:2 sanctified. Someone or something that God had consecrated for his own special use. In the OT, God set apart Israel from the nations; here Paul refers to believers in Jesus, consecrated by God for his use.

1:3 Grace and peace to you. The conventional greeting was chairein, which early Christians often changed to charis, “grace.” The Jewish greeting (sometimes added to chairein) was “peace.” Letters frequently included prayers or blessings for their recipients; Jewish people used “peace” as a blessing, meaning that they implicitly asked God to give the recipient well-being. from God . . . and the Lord Jesus Christ. Because Paul invokes Jesus as well as the Father in this blessing, he takes for granted here Jesus’ deity.

1:4–8 Speakers usually started with something positive about their audience to secure a more favorable hearing.

1:4 I always thank my God for you. Letters sometimes included thanksgivings.

1:5 all kinds of speech and . . . knowledge. Corinthian culture particularly exalted, and even competed in, skills of speech and knowledge, including extemporaneous speeches on random topics. The believers valued especially those spiritual gifts (v. 7; 12:8–10) that were valued, in a more secular form, in their culture.

1:8 on the day of our Lord Jesus Christ. Scripture spoke of the day of the Lord (e.g., Isa 13:6, 9; Joel 1:15; 2:1, 11, 31); Paul applies this language to the return of Jesus, who is divine (see note on v. 3). In the Greek world, even Jews often neglected emphasis on God’s future promises; this may be one area where the Corinthian believers need correction (see 3:13–15; 4:5; 5:5; 6:14; 11:26; 13:8–12; 15:12–57).

1:10 that all of you agree with one another in what you say. Speakers and writers sometimes stated their thesis before arguing it. Here in v. 10 Paul notes that he is appealing for unity (1:10–4:21). Factors in disunity may include the perspectives of different social levels (cf. 11:21) and possibly the different house churches (cf. 16:19), though some argue that these also met together sometimes (cf. Ro 16:23). divisions. Division and rivalry were rife in antiquity (in sports and especially speech and politics), and ancient speakers and writers often had to exhort hearers to unity.

1:11 some from Chloe’s household have informed me. Travelers often carried letters, oral news and their eyewitness testimony; hearers could cite the travelers if the reports were deemed reliable. Chloe’s household. Chloe may have owned a business in Corinth or Ephesus; trusted servants or freed persons would be considered members of her household, and they would travel between these major mercantile cities on business.

1:12 Urban hearers in places such as Corinth regularly judged and ranked speakers. Students of rival teachers sometimes fought; in one later case slaves of an orator’s disciples beat to death a mocker. Disciples sometimes treated teachers as fathers (cf. 4:15). I follow. Lit. “I am of”; the phrase was sometimes used as a slogan of ancient political partisans, which Paul caricatures here. Though some disdain Paul for his speaking ability, he here uses anaphora, a type of rhetorical repetition that begins successive phrases in the same way. Many scholars think that the only actual division at this time was between partisans of Paul and those of Apollos, since they are the only groups subsequently addressed (cf. 3:4–6, 22; 4:6). Cephas. Aramaic; the Greek translation is Petros, Peter.

1:13 Speakers sometimes reduced their opponents’ arguments to the absurd by how they represented them, often using multiple rhetorical questions to build emotional force.

1:14 baptize. Besides the sea, Paul could have baptized in Corinth’s many public fountain houses or especially public baths. Crispus and Gaius. Corinth’s legal citizens were Roman citizens; although the names Crispus (cf. Ac 18:8) and Gaius do not guarantee Roman citizenship, they are Roman names.

1:16 Informal letters sometimes included afterthoughts; but speakers also sometimes corrected themselves deliberately to drive home a point. Either interpretation may be possible here. household. In matters of religion, Gentiles expected household members to follow the free male household head.

1:17 Christ did not send me to baptize. Gentiles who converted to Judaism understood baptism as part of the act of conversion; Jesus’ movement adopted the same action. But Paul does not want even this act to detract from emphasis on the cross. not with wisdom and eloquence. Corinth highly valued wisdom and speech (see notes on vv. 5, 20). Philosophers and moralists often used rhetorical (oratorical) skills, but emphasized that it was the truth, not mere rhetoric, that convinced their hearers. Paul’s rhetorical devices in this section could include antithesis (vv. 18, 25), paradox (v. 25, also using antithesis), and most clearly, anaphora (vv. 12, 20, 26) and antistrophe (see note on vv. 27–28).

1:18 the cross. A terrifying instrument of execution by slow torture; although rare in Corinth, in Judea it epitomized Roman repression. Romans reserved the punishment especially for slaves and rebel provincials, the antithesis of “savior” benefactors, who could be gods, kings or the wealthy. Jews deemed accursed those who were hanged on stakes (Dt 21:23). foolishness to those who are perishing. Corinth valued honor, wealth and social power.

1:19 See Isa 29:14 (part of the context cited by Jesus in Mk 7:6–7).

1:20 The Greco-Roman world’s two advanced disciplines were philosophy and (more commonly useful for statesmen) rhetoric. philosopher of this age. Lit. “debater of this age” and may refer to rhetoricians, whom philosophers often criticized; “wise person” here may condemn philosophers also. Paul here uses four rhetorical questions to drive home the point, plus anaphora (three times repeating “Where is . . . ?”); cf. Isa 19:12; 29:14; 33:18; 44:25; Jer 8:9.

1:22 Greeks look for wisdom. Others associated Greeks with philosophy, which means “love for wisdom” (cf. Ro 1:14). Various competing philosophic schools, however, promoted different beliefs; see the article “Ancient Philosophies.”

1:24 the power of God and the wisdom of God. Jewish tradition sometimes personified divine Wisdom (following Pr 8).

1:25 foolishness of God . . . weakness of God. In speaking of God’s “foolishness” and “weakness” Paul uses the accepted practice of irony. Corinthian culture valued powerful persons (cf. v. 26).

1:26 Not many of you. Only a few people in antiquity, fewer than 1 percent, belonged to the truly elite class or the very wealthy; prosperous Corinth would have more people of moderate wealth, but the poor still constituted the majority of the city. In Corinth, even most of the wealthy descended from people of lower class or freed persons, not from a hereditary nobility. Paul three times opens clauses with “not many”; opening repetition, or anaphora, would help hold the attention of rhetorically sensitive Corinthians. Some church members, perhaps especially those who owned the larger homes in which the churches met, may have been of higher status (cf. Ro 16:23). They would be few but disproportionately influential. Many people lived in apartments only large enough for sleeping, but the wealthy could live in larger ground-floor apartments or in separate homes. The wealthiest district in Corinth proper was the Kraneion, or Craneum.

1:27–28 God chose . . . God chose . . . God chose. Paul’s threefold repetition is rhetorical antistrophe (repeating a phrase at the end of a line; the phrase appears at the end in Greek, though most translate it at the beginning in English). Paul here develops the three examples from v. 26—the wise, the powerful and the honored aristocrats.

1:29 no one may boast. In vv. 26–29, Paul vaguely echoes Jer 9:23, which warns against the wise, strong and rich boasting in their gifts; this prepares for Paul’s explicit quotation of Jer 9:24 in v. 31.

1:30 who has become for us wisdom. Greeks and especially Jews sometimes treated wisdom as a personification or even a being; for Jewish people, it was the best way to imagine something divine in character yet distinguished from God the Father (see 8:6; see also note on Jn 1:1). They also viewed God’s law as their wisdom and righteousness (Dt 4:6; 6:25).

2:1 eloquence or human wisdom. When an orator came to a city, he would often offer a scheduled oration; if this speech brought him enough reputation that he could begin teaching students rhetoric, he would make that city his home. By contrast, Paul sought to honor Christ, not himself (v. 2). Even famous orators frequently began a speech by playing down their speaking abilities, knowing that their skill would quickly become obvious. While many of Paul’s letters display brilliant thought, however, his speaking style (cf. v. 3) fell short of his critics’ expectations (2Co 10:10; 11:6). Although Josephus, to please his Hellenistic audience, tendentiously presents Moses as a great orator, Paul’s rhetorical limitations apparently had some Biblical precedent (Ex 4:10; Jer 1:6).

2:3 weakness. Critics complained about speaking skills even if one’s arguments were strong but one fell short in appearance or delivery (cf. 2Co 10:10), such as gestures and voice intonation. fear and trembling. The OT and Jewish sources applied this phrase in various ways, sometimes emphasizing appropriate reverence for God and sometimes fear of powerful enemies. Against some philosophers, rhetoricians urged speakers to rouse emotion; audiences would often ridicule a speaker who trembled.

2:5 might not rest on human wisdom, but on God’s power. Criticisms by Socrates and others had led many rhetoricians by this period to admit that rhetoric could be abused—one could market false ideas and persuade people to believe wrong things. Nevertheless, they contended that rhetoric remained essential, for if one had truth one should promote it. Still, speakers also deployed rhetoric in law courts to amplify accusations and commit character assassination.

Philosophers had criticized rhetoric at least since the time of Socrates, valuing truth over skillful speech. By this period, however, philosophers usually used the persuasive devices rhetoricians had identified. Paul would have sided with the philosophers’ critique of rhetoric, but like them he was willing to use it. He employed in his letters many rhetorical devices familiar from his milieu, even though he demeaned depending on rhetoric. Despite his deficiencies in critics’ eyes (2Co 11:6), he communicated as skillfully as possible in his context while also depending on the Spirit to transform hearts (v. 4). power. Rhetoricians sometimes spoke of argumentative “demonstration” (cf. v. 4) and rhetorical “power,” but Paul depended instead on the message of the cross (1:18, 24; 2Co 13:4), perhaps accompanied by signs (1:22, 24; Ro 15:19).

2:6 mature. Philosophers could apply this descriptor to those advanced in wisdom—which the Corinthians lack (3:1). But as a Jewish work from this period put it, even one considered “perfect” or “mature” was useless without God’s wisdom (Wisdom of Solomon 9:6).

2:7 before time began. Jewish tradition emphasized that God formed wisdom before the world, used it to form the world, and that wisdom would endure forever.

2:8 this age. Jewish people contrasted this ruined age with the eternal age to come. This age’s rulers had human power that would pass away (1:27–28); God’s wisdom in the cross is eternal (1:18–25). Lord of glory. Jewish sources normally reserved this title for God; “Lord of glory” can also be translated idiomatically as “glorious Lord.”

2:9 Interpreters often slightly adapted the wording of quotations; Paul adapts Isa 64:4 (possibly with wording from Isa 65:17), then quaifies it (v. 10; cf. v. 16).

2:10 revealed to us by his Spirit. The prophets promised the Spirit for the coming age; the Spirit’s activity now thus provides a foretaste of that age.

2:11 no one knows the thoughts of God except the Spirit of God. Jewish thinkers in this period recognized that people could understand God’s plans only by the gift of his wisdom and his Spirit (cf. Wisdom of Solomon 9:17; see note on 1Co 2:16).

2:12 spirit of the world. The Greek term for “spirit” also means “disposition,” and so it need not be personified here.

2:14 without the Spirit. The Greek term translated thus here (the context does imply the NIV’s interpretation) might reflect a Diaspora Jewish interpretation of Ge 2:7 (see discussion at 1Co 15:44–46, where the NIV translates the same term “natural”).

2:16 Isa 40:13, cited here, was a rhetorical question denying that humans knew God’s Spirit, but because the Spirit has now come (cf. Isa 44:3; Joel 2:28), God’s people do have his Spirit. The Greek translation of Isa 40:13 substitutes “mind” for “Spirit”; Paul, who has been writing about God’s Spirit in vv. 10–15, draws on both ideas.

3:1 mere infants in Christ. Thinkers frequently depicted the unlearned as babies who needed milk (cf. note on 9:7). The image was acceptable for beginning students, but insulting to those who thought themselves mature in wisdom.

3:3 worldly. Lit. means more like “resembling what is fleshly”; for the sense, see the article “Flesh and Spirit.”

3:4 mere human beings. Probably meant as biting irony; for Greeks, the line between human and divine was much thinner than for Jews and equally monotheistic Gentile Christians. Here Paul’s hearers are acting like people devoid of God’s Spirit (cf. 2:14–3:3).

3:7 Agrarian metaphors were common in antiquity; farmers planted and irrigated but their prayers and offerings confirmed that most of them understood that only God could make plants grow.

3:8 rewarded according to their own labor. Farmers’ reward was the harvest, when they could pay landowners (on whose estates many of them worked) and the like. Some Jewish sources compared the time of the end with a harvest.

3:9 God’s field, God’s building. Paul uses familiar images: in Scripture, God planted and built up his people (e.g., Jer 18:7; 24:6; 31:28; 45:4).

3:10–11 Paul develops the building image from v. 9 (the temple, vv. 16–17). Believers should not divide over Paul and Apollos (vv. 5–7), whose job was to build them on Christ.

3:13 the Day. The day of the Lord (cf. 1:8), associated with the fire of God’s judgment (Zep 1:18; cf. Isa 66:15–16). bring it to light. Daylight reveals what is hidden (see 4:5). fire will test the quality of each person’s work. The fire that purified metals destroyed wood and straw. Scripture used metal refining as a metaphor for testing or purifying by judgment (Zec 13:9; Mal 3:2–3), and fire consuming straw to depict the destruction of the wicked (Isa 33:11–12; 47:14).

3:14–15 builder will receive his reward . . . suffer loss. The metaphor fits: builders do not get paid for shabby construction. The structure here is the church as God’s temple (vv. 16–17); judgment day would reveal the degree of builders’ (such as Paul’s and Apollos’s) true effectiveness (vv. 12–13).

3:17 If anyone destroys God’s temple, God will destroy that person. Almost everyone in antiquity believed that deities avenged any violation of the sanctity of their temples, especially against those who destroyed such temples. Yet those not building but rather tearing down the temple—those sowing division in the church—violated its sanctity. you together are that temple. Some thinkers in antiquity envisioned spiritual sacrifices and temples; some passages in the Dead Sea Scrolls apply the image of the temple to God’s people.

3:18 become “fools” . . . become wise. Paul continues arguing that the wisdom of this age is folly; see 1:17–31; 2:1–16 (especially 2:6–8). Paul further demonstrates this point from Scripture in vv. 19–20.

3:19 He catches the wise in their craftiness. Although Job’s accuser Eliphaz uses this wisdom out of context in Job 5:13, the principle remains a wise one.

3:20 In the context of Ps 94:11, cited here, God shows the foolishness of the wicked who fail to recognize that the sovereign God sees and will judge their deeds (Ps 94:7–10).

3:21 All things are yours. Some philosophers claimed that everything belonged to the gods and they were friends of the gods, so everything belonged to them. (By this the most extreme meant that they were free to use anything; they often slept, and sometimes openly excreted, on porches of temples and the like.) Many Jewish people believed that God’s people were heirs who would rule the coming world (see note on Ro 4:13). Paul argues that not only apostles who labored to build the church up, but also everything else in this world, was for the benefit of the church, God’s temple. Their ministers were there to serve them, not to be celebrities to follow and divide over.

4:1 those entrusted with. A phrase normally applied to managers of estates, who were sometimes high-level servants, as here (continuing the thought about Paul and Apollos from 3:5, 9, 22; cf. 4:6).

4:3 human court. The context invites the NIV to render “human day” as “human court,” but the Greek term for “day” Paul uses also implies a contrast with the day of the Lord, associated with the day of judgment that is implied in v. 5 (see notes on 1:8; 3:13; 5:5; cf. Ro 2:5).

4:5 Cf. Ps 139:11–12; Da 2:22.

4:6 Do not go beyond what is written. Most people in antiquity understood that it was inappropriate to boast beyond their proper status in life. Scholars debate the meaning of not exceeding “what is written”; some envisage the background in schoolchildren tracing the writing of their teachers; or people finding harmony by observing an earlier agreement; or most likely, given Paul’s usage elsewhere (e.g., 1:19, 31; 2:9; 3:19), to not violate Scripture. This would include his earlier warnings in this letter not to rely on mere human wisdom (1:19; 3:19).

4:8 Speakers commonly used irony to drive home a point. Philosophers often claimed to have true wealth, wisdom, power, and the right and wisdom to rule; Paul ironically treats the Corinthian believers as greater sages than himself and Apollos, the Corinthian believers’ teachers. Paul’s audience, who respected teachers, would surely recognize the irony, in effect challenging their own pretentious claims to wisdom. Corinthian culture boasted in wealth and status. God’s people would reign in the future (6:2).

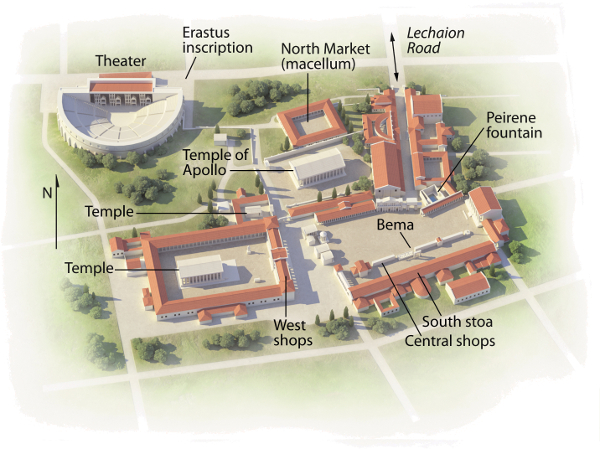

4:9 on display at the end of the procession. Some others depicted the wise as exhibited in the theater of the world, but as a matter of honor; here it is an image of shame. The person in charge of games in amphitheaters would exhibit the gladiators who would battle wild beasts there; here God himself exhibits the sufferings of the apostles. “At the end of the procession” is simply a Greek term meaning “last” (contrast the divine view in 12:28); it could mean captives led in triumphal procession before execution (2Co 2:14), or, with likelier reference to the arena (see 1Co 15:32), that they were the final show for the day—normally reserved for the most wretched criminal condemned to die in the arena. Corinth’s theater seated 18,000.

4:10 See note on v. 8; cf. 1:25.

4:11–13 Some ancient philosophers provided lists of their hardships, as here, to demonstrate their integrity in following their teachings about endurance and contentment. Cynics, the most radical Greek sages, fit the description in v. 11, as would most people who were homeless. But cf. also the demands of radical mission for Jesus’ disciples (Mk 6:8–11).

4:12 work hard with our own hands. People of status considered manual labor (Ac 18:3; 20:34) demeaning; with some notable exceptions (such as many Jewish teachers), many sages in antiquity avoided it. (Cynics begged; most other Gentile sages charged tuition or depended on wealthy patrons.)

4:13 slandered. Some of the church’s more socially respectable members may have counted Paul’s work an embarrassment. answer kindly. Some philosophers tried to disregard human opinion, ignoring criticism; Cynics, however, often insulted their hearers (and not only those who criticized them). For blessing those who curse, see especially Lk 6:22 (cf. also Pr 15:1; 29:8).

4:14 as my dear children. The gentler sages usually warned their students gently, sometimes as their children. Disciples sometimes viewed their teachers as fathers, and teachers viewed them as their children.

4:15 ten thousand guardians in Christ. In contrast to v. 14, the Greek term translated “guardians” referred to slaves who ensured the safe transit of boys to and from school.

4:16 imitate me. Disciples often learned from their teachers’ behavior; children also imitated parents (see note on v. 14).

4:17 Timothy, my son. See note on v. 14. my way of life. See note on v. 16.

4:19 if the Lord is willing. Both Jews and Gentiles sometimes conditioned their plans with phrases such as, “If God wills . . .”

4:21 rod of discipline. Paul continues the image of ancient fathers (see vv. 15–17), who often used a rod or stick for discipline. Corinthians, influenced by Roman values, would have appreciated gentle and indulgent fathers, but also understood that fathers placed duty first and could be stern.

5:1 A man is sleeping with his father’s wife. Nearly all ancient Mediterranean cultures (as well as nearly all cultures in history) viewed parent-child incest as unimaginably terrible and divinely punishable. This offense included, as probably here, stepsons with stepmothers (Paul borrows language here from Lev 18:6–8). After divorce or becoming widowers, Greek and Roman men often married wives who were much younger (Greek men did this also at their first marriage), so the stepmother was sometimes closer in age to the eldest son than to the father. (In divorce, children normally went to the father.)

5:2 you are proud! Some suggest that the man was a high-status member in whom the congregation took pride; such a man would also have important social connections that could affect the church’s standing in the community. put out of your fellowship. Cities usually allowed groups of resident aliens to discipline members according to their group’s laws, provided they did not exceed Roman law. (Members could refuse the discipline by rejecting their group, but this could leave them socially isolated.) Thus local synagogues could administer various levels of discipline, including beatings (2Co 11:24); their harshest discipline was long-term expulsion from the Jewish community.

5:3, 4 with you in spirit. Ancient letters used expressions such as this one to communicate intimacy; they were not intended as literal metaphysical presence (or normally even direct spiritual observation, as in 2Ki 5:26).

5:5 hand this man over to Satan. On exclusion from the community, see note on v. 2; some Jewish people understood such exclusion as exclusion also from the world to come, unless (as is Paul’s hope here) it induced repentance and consequent restoration. the day of the Lord. See note on 1:8; cf., e.g., Eze 30:3; Am 5:18, 20; Zec 14:1; Mal 4:5.

5:6 yeast. Fermented dough (leaven) pervades the dough, hence could apply figuratively to something (here, sin) that infects the whole. Acceptance of sin could contaminate and remove God’s blessing from the whole community (Jos 7:5, 12–13, 25).

5:7 a new unleavened batch . . . our Passover lamb. Passover commemorated God redeeming Israel from Egypt. When God struck the Egyptian firstborn to make Pharaoh release God’s people, he passed over Israelite homes, where he saw the blood of the Passover lamb. The lamb was understood as a sacrifice (Ex 12:27); Jewish people expected a new redemption (cf. Mic 4:10; Zec 10:8). Passover introduced the Festival of Unleavened Bread, which commemorated how Israel left Egypt in haste, without time to leaven their bread.

5:10–11 Speakers and writers commonly listed vices. The lists varied in length; the longest ancient list known to us includes more than 100 vices.

5:11 sexually immoral. Most free Roman and especially Greek men had intercourse with slaves or others before marriage; Jewish tradition emphasized Gentile sexual immorality. Do not even eat with such people. As in Jewish communities, exclusion from the community (vv. 2–5) prohibited members from eating with the excluded person (v. 11).

5:12 judge those outside the church. Local groups of resident aliens in cities (such as Diaspora Jews) were normally expected to handle violations of their customs within their communities themselves, provided they did not break Roman laws in doing so (e.g., by executing someone).

5:13 Expel the wicked person from among you. For both sexual sins (Dt 22:21, 24) and other major transgressions (Dt 13:5; 17:7; 19:19; 21:21; 24:7), Biblical law commanded expelling the wicked from the community by executing them. Romans did not permit subject peoples to execute transgressors, so Jewish people often commuted the punishment to banishment, as here.

6:1 before the ungodly for judgment. Roman urban society was rife with lawsuits; in some places court sessions ran from sunrise to sunset, with the numerous cases of poor petitioners each decided swiftly (sometimes in a minute). People of status more often gained a significant hearing, and judges, who came from the elite, favored members of their own social class. Magistrates sometimes assigned criminal cases such as treason, murder and adultery to juries rather than judges. Some people sued others just to inconvenience them; most disputes involved property. Wealthy and influential people sometimes helped arbitrate such cases privately.

6:2 the Lord’s people will judge the world. Many Jewish people expected God’s people to rule in the future era (e.g., Wisdom of Solomon 3:8).

6:6 one brother takes another to court. Minority groups within a city were permitted to (and supposed to) settle their own internal affairs. Prejudice against such minorities made more public cases even more damaging to their precarious reputation. Common as lawsuits were between brothers (often over inheritance issues), suing family members was deemed scandalous; Paul applies the same principle to spiritual brothers (his usual meaning for “brother”).

6:7 that you have lawsuits among you. Many philosophers suggested that one should not sue anyone, since property did not matter. Paul presumably knows Jesus’ instruction (Mt 5:39–40; Lk 6:29–30), but welcomes settling matters within the community of believers (see note on v. 6).

6:9 wrongdoers will not inherit the kingdom of God. Paul agrees with Jewish teaching, though this warning would not apply to those who had left such lifestyles. This future for “wrongdoers” contrasts with the promised reign of God’s people in vv. 2–3. Do not be deceived. Ancient writers often warned against being deceived (cf. Mk 13:5). Both Jewish and Gentile writers often included vices in lists (see 5:10–11). Jewish people regarded most Gentiles as sexually immoral and based on Scripture also condemned the other sins in 6:9–10. men who have sex with men. Cf. Lev 20:13; see the article “Homosexual Activity in Antiquity.”

6:11 what some of you were. Because God had consecrated his people to himself, they were to live as holy (consecrated for God; Lev 20:26). Likewise, those transformed by Jesus and the Spirit needed to live accordingly.

6:12 Ancient writers and speakers often cited and then refuted the objections of imaginary interlocutors, as Paul very likely does here (countering alleged rights with what is beneficial); cf. notes on 1:12; 7:1. right to do anything . . . but not everything is beneficial. Both courts and philosophers reasoned whether actions were permitted and beneficial. will not be mastered. Philosophers often warned against being enslaved or controlled by any desire.

6:13 Food for the stomach. Ancient moral thinkers commonly depicted pleasures as “the belly” (cf. Ro 16:18; Php 3:19). The imaginary interlocutor here implies that the body is designed for intercourse. Because Greeks viewed the body as temporary (for many, in contrast to the immortal soul), the interlocutor also may object that what one does with the body does not matter.

6:14 he will raise us also. Paul appeals to the body’s future resurrection, a point he develops in detail in 1Co 15. Those who believed in future judgment often charged that teaching’s detractors with greater susceptibility to immorality.

6:15–17 Paul appeals not only to Scripture but to the good news that saved them. Because they belong to Christ’s body (cf. 12:12–13), sleeping with prostitutes was like desecrating Christ’s body as well as one’s own. Prostitution was common (see the article “Prostitution and Sexual Immorality”), and Corinth had a particular and long-standing reputation for it.

6:17 one with him in spirit. Ge 2:24 (cited in v. 16) applied to marriage, but Paul applies the principle to all intercourse. Yet Scripture taught that God was married to his people (Isa 54:5–6; Hos 2:20), a principle Paul applies to believers’ unity with Christ in one body.

6:18 Flee. Writers on moral topics frequently urged their hearers to flee vices (cf. 10:14), including sexual ones. All other sins a person commits are outside the body. Some attribute this line (the word “other” does not appear here in Greek) to the interlocutor, whom Paul refutes by showing that sexual sin dishonors one’s own body.

6:19 bodies are temples of the Holy Spirit. Some Jewish people depicted God’s people as a spiritual temple (see note on 3:17), an image Paul applies here also to individual believers. Some ancient shrines reportedly practiced sacred prostitution; in old Corinth, prostitutes were reputed to be dedicated to Aphrodite, their patron goddess.

6:20 bought at a price. In the OT, God redeemed, or bought, his people (Ex 15:16; Ps 74:2); believers were bought by Christ (1Co 7:23; cf. 5:7). (“Redemption,” as in 1:30, means freeing a slave, sometimes by paying ransom.) This price of infinite worth contrasts starkly with the demeaning price paid to hire a prostitute. honor God with your bodies. The Greek term for “price” here can also mean “honor,” perhaps leading to the play on honoring God with your bodies, though this phrase uses a different verb (cf. 1Th 4:4).

7:1 Now for. Sometimes used by ancient writers, as here, to transition to a new subject (the same Greek phrase appears in 7:25; 8:1; 16:1, 12; 1Th 4:9; 5:1, where the NIV usually translates “now about”). It is good for a man not to have sexual relations with a woman. Many scholars believe that this is a quotation from (or paraphrase of) the Corinthian believers’ letter to Paul (cf. 6:12–13). To the married, Paul then responds in vv. 2–7: avoiding intercourse is not good with one’s spouse (cf. Ge 2:18).

7:2 have sexual relations with. The NIV correctly interprets a more euphemistic Greek phrase that normally had this meaning. Jewish teachers and even some Gentiles viewed marital intercourse as the best deterrent to extramarital sexual relations (cf. Pr 5:19–20).

7:3 marital duty. Marriage contracts often stipulated duties; Judean marriage contracts required husbands to grant their wives intercourse. Strong advocates of marital intercourse, rabbis debated whether the maximum period a husband could deprive his wife was one week or two (apart from exceptions such as the husband being on a voyage, away to study Torah, and so forth). Paul does not specify a period here, but he clearly advocates marital relations.

7:4 authority over her own body. Philosophers sometimes depicted intercourse as submitting to another’s power (cf. 6:12); most people were not philosophers, but Romans in general thought of a dominant (masculine) and submissive partner in intercourse. In the same way. Many Gentiles expected only the wife to be faithful. Paul’s application to both genders here is important.

7:5 Do not deprive each other. Like his fellow Judean teachers, Paul urges married couples not to abstain for long periods (see note on v. 3). tempt. See notes on vv. 2, 9.

7:6 as a concession. Jewish law permitted concessions for human weakness; Paul allowing some abstaining in v. 5 (“perhaps by mutual consent) is merely his concession to their wishes (see note on v. 1).

7:9 better . . . than to burn with passion. Greek sources frequently speak of passion as a wounding or burning fire; whereas Greek romances celebrate such craving, Paul wants believers free from this distraction.

7:10 A wife must not separate from her husband. Paul cites Jesus’ teaching against divorce (see Mk 10:11–12 and notes).

7:11 a husband must not divorce his wife. Apart from wealthy households, only men could normally initiate divorce in Judean culture (though if the man were abusive or very negligent, a woman could petition elders to compel her husband to grant a divorce). Greek and Roman practice, relevant for Corinthian society, was very different: remaining married required mutual consent, so either party could divorce the other with little notice. Financial arrangements and relationships between families deterred simply divorcing because of, say, an argument. Nevertheless, divorce was widespread in Corinth, as in many other cities; many believers were likely already remarried before their conversion.

7:12–13 Paul must address a situation not specifically envisioned in Jesus’ general principle (see vv. 10–11 and notes). Many Corinthian Christians were already married to nonbelieving spouses when converted; divorce practice in Corinth allowed either party to unilaterally end the marriage. Paul, however, rejects spiritual incompatibility as grounds for divorce.

7:14 your children . . . are holy. Roman laws addressed the status of children in marriages between classes or between Roman citizens and provincials; Jewish laws addressed whether the offspring of Jewish-Gentile unions were Jewish; and so forth. In ancient divorces, custody of the children normally went to the father.

7:15 But if the unbeliever leaves, let it be so. Paul qualifies here Jesus’ general principle (see vv. 10–11 and notes), which was not designed as a law covering all situations. In Greek and Roman marriages, either party could dissolve the marriage unilaterally by leaving it. not bound. What happens when the marriage is dissolved against the believer’s will? In divorce contexts, the meaning of “not bound” is clear; this was the precise language in Jewish divorce contracts for freedom to remarry.

7:17 live . . . in whatever situation the Lord has assigned. Greek philosophers, especially Stoics, emphasized accepting one’s situation (although one was welcome to change it if possible and if the change was beneficial, vv. 21–24). But whereas Stoics identified the God who directed their lives with Fate, Paul trusts God as a loving Father.

7:18 become uncircumcised. Greeks exercised naked, and when Greek culture invaded Judea two centuries earlier, adherents of its “progressive” culture ridiculed Jews for circumcision. Some Jews therefore submitted to an operation to pull the remains of their foreskin forward and make them appear uncircumcised. Other Jews regarded this procedure as an act of apostasy.

7:21 if you can gain your freedom, do so. Even full-scale wars to free slaves had failed, and the small minority of thinkers who rejected slavery in principle lacked means to change the institution. Urban household slaves, the sort addressed here, could face significant hardships, but at other times wielded significant influence and power. In a few cases, slaves of powerful aristocrats wielded more power than some other free aristocrats (see Introduction to Philemon: Situation). Nevertheless, freedom was the better option when possible; slaves who earned money could purchase their freedom. In many other cases, slaveholders freed them to reward their service—or because they did not want to provide for them in their old age.

7:22 the Lord’s freed person. Under Roman law, a freed slave continued to belong to his or her former holder’s extended household and to have some obligations to honor the former holder. Likewise, the former holder was obligated to help the freed person with connections and money; much to the chagrin of some aristocrats, some enterprising freedmen achieved greater wealth than hereditary aristocrats. Many of Corinth’s residents were Roman citizens, and slaves they freed normally became Roman citizens themselves. Many of Corinth’s residents descended from freed persons.

7:26 good for a man to remain as he is. During times of intense hardship (see vv. 29–31), including the expected period just before the end, marrying and having children could just make matters more difficult (cf. note on Mk 13:17).

7:27 pledged . . . free. The NIV translation of Greek terms here as “pledged” and “free” might make sense if Paul addresses fiancés of virgins (Paul mentions “virgins” in v. 28; see note on v. 36). More likely, Paul simply mentions groups he has already discussed in vv. 12–16 (see note there), and adds “virgins” in v. 28 just by way of comparison. The term that the NIV translates as “pledged” here usually means “married”; the term it translates as “a woman” often means “wife,” which is how the NIV translates it later in the same verse. The term first translated “released” and then translated “free from such a commitment” later in this verse is literally “freed,” hence would normally mean “divorced” (the term could also mean “widowed,” but that sense does not fit its first use in this verse). This verse therefore probably addresses marriage and divorce, along with divorce and remarriage, although qualifying the statement in v. 28, presumably at least for the sorts of situations noted in 7:15.

7:29–31 These verses describe a time period just before the end times. See note on v. 26.

7:32–34 Cynic sages feared that marriage would distract them from the freedom of the Cynic lifestyle, which included no possessions and no responsibilities. Paul acknowledges that family responsibilities can distract from pure focus on the kingdom, although he has also acknowledged that some will be more distracted without marriage (v. 9) and later notes that most apostles were married (9:5).

7:36–38 Mothers and especially fathers, normally consulting with their children, arranged their children’s marriages. Some scholars believe that Paul addresses virgins’ fathers here, translating accordingly (e.g., NASB); although the matter remains debated, the NIV follows the more common interpretation, that Paul addresses virgins’ fiancés. Betrothal involved an official agreement between families; breaking betrothals was therefore an official act. Jewish men often married around age 20 and usually married women just a few years younger; Greek men often married around age 30 and married women about 12 years their junior; the ages in Roman marriage generally fell between these ages.

7:39 if her husband dies, she is free to marry. One traditional romantic ideal in antiquity was the widow who never remarried (cf. Lk 2:36–37), but Augustus’s tax policy had encouraged younger Roman widows to remarry, and remarriage after a spouse’s death was common (cf. 1Ti 5:14).

7:40 I too have the Spirit of God. Ancient Jewish circles often associated the Spirit with prophetic inspiration.

8:1 We all possess knowledge. Some Corinthian believers may have been making the claim that there is just one God (v. 4), so they can eat sacrificial meat (v. 7). On Paul recounting their views, see notes on 6:12, 13; 7:1.

8:4 Idols, or deity statues, were in fact worthless (Isa 44:9–20; 46:5–7), and there is only one God (Isa 45:5–6, 18, 21–22; 46:9). Unfortunately, some were using this truth to justify eating sacrificial food (v. 7).

8:5 many “gods” and many “lords.” Like other Gentile cities, Corinth was full of deities. Among the most highly honored deities in mercantile Corinth were Poseidon/Neptune, god of the sea; Aphrodite/Venus, goddess of sexuality; and the emperor.

8:6 but one God. Many philosophers spoke similarly of one supreme God over the other deities, as many Diaspora Jews were happy to remind them. The cornerstone of Jewish faith was the confession that there was one God and Lord (Dt 6:4); Paul adapts the wording to apply to both the Father and Jesus. Jewish tradition affirmed that God used personified Wisdom to design and form creation, a role here applied to Jesus (cf. 1Co 1:30). from . . . for . . . through. Using different prepositions, ancient intellectuals often distinguished kinds of causes, including material (“from”), instrumental (“through”), modal (“in” or “by”) and purpose (“for”).

8:9 Although Paul’s general point is clear, the specific background here is debated. exercise of your rights. Some argue that “rights” indicates their citizen rights to eat at festivals. It might simply refer, however, to the authorization to eat sacrificial food being claimed by the “strong.” become a stumbling block to the weak. Some regard “the weak” as those with less social power, who cannot afford food except at festivals and therefore associate all meat consumption with idols. Paul might simply refer, however, to their weaker conscience, perhaps defined as weaker by the “strong” (vv. 7, 10, 12; 10:28–29). Philosophers often claimed that “all things” belonged to them (cf. notes on 3:21; 4:8); many despised human opinion, and some despised human custom. Jewish teachers, however, generally warned about doing what could set a bad example for those who misunderstood. For them, nothing was worse than causing another to stumble, i.e., to fall from the right way and be excluded from the world to come.

8:10 eating in an idol’s temple . . . what is sacrificed. Although the sacrificial status of food offered in the market was not always clear, food available in the temple had clearly been sacrificed.

9:1 Am I not free? Philosophers valued being “free” (cf. v. 19; 10:29)—free from concern about others’ opinions of them, free from false ideas and also often free from property concerns and thus being self-sufficient. Freedom was frequently associated with rights (cf. 8:9); thus Paul, who invites the Corinthian believers to sacrifice some of their rights, offers an example of surrendering his own (vv. 4–6, 12, 18).

9:2 seal. Imprints made by signet rings in hot wax could attest or authenticate a document; by extension, a seal could thus mean an authentication.

9:3 my defense. Although digressing in ch. 9 to offer himself as an example (as sages sometimes did), Paul also offers something of a defense. Defense (and some other) speeches often drove home a point with a series of rhetorical questions (vv. 4–8, 12–13). More elite members may have found Paul’s artisan work (4:12) an embarrassment among peers of their own status: in their setting, more respectable sages depended on patrons or tuition. For the elite, manual labor was for those not worthy of support. Probably sometime after this letter, rival teachers play on this concern about Paul (2Co 12:13–18).

9:5 right to take a believing wife along with us. Most people in antiquity married and took this expectation for granted (see the article “Celibacy in Antiquity”). Cynics and other wandering sages, in contrast to stationary teachers, normally could not marry; this was presumably also the case for John the Baptist, Jesus, and earlier, Jeremiah (Jer 16:2). Even disciples who left home to study Torah might be away from their wives for weeks or more at a time. Given the size of Galilee, Jesus’ disciples were probably rarely more than two or three days’ distance from their families, but those who were married (such as Peter; Mk 1:30) did not bring their wives at that time. (Most men did not marry before 18, and disciples were typically younger than that.) Whether because children were grown or because distances were greater, however, most apostles by the time that Paul writes were married and traveled with their wives.

9:6 right to not work. Among Gentiles, the most respectable means of support for sages were dependence on a wealthy patron or charging tuition. Elites despised manual labor, though artisans did not feel the same way. Most people looked down on the other common means of support—begging—but Cynics took pride in how this practice disdained human honor. Many Jewish sages did respect manual labor.

9:7 soldier at his own expense. Many common soldiers working for Rome earned about three drachmas a day (far more for centurions; legionaries earned more than auxiliaries); three drachmas amounts to more than three denarii, hence roughly three days wages for an average worker in much of the Roman Empire in this period. Retirement benefits were significant for those who survived the full 20 years of service. plants . . . and does not eat. Tenant farmers paid landowners a share of the crops but normally retained a significant amount for their own use. tends a flock and does not drink. Urban residents had more access to cheese than milk, but sheep and goat milk were more common in the countryside.

9:9 Do not muzzle an ox while it is treading. Jewish interpreters often recognized Biblical injunctions regarding kindness toward animals (as in Dt 25:4) as instilling kindness that should also be applied even more fully toward people.

9:12 we did not use this right. In antiquity, many people mistrusted traveling sages as seeking others’ money; Cynics even begged on the streets. Other sages worked to counter the stereotype that sages were greedy. If Paul depended on the support of wealthy Corinthian Christians, he could be viewed as their client (see note on v. 6). Patrons expected such dependent sages to please them, but Paul maintains his independence—his “freedom” (see vv. 1, 19)—so he can preach truth. rather than hinder the gospel. Philosophers often claimed to be unconcerned with others’ opinions of them, but some did seek to avoid offending others needlessly; Paul labors to avoid being classified with stereotypical greedy sages.

9:13 food from the temple. Priests in most ancient temples (including Israel’s, Lev 6:25–26, 29; 7:5–6; Eze 42:13) had the right to eat assigned portions of the sacrificial food (see also the article “Sacrificed Food”).

9:14 the Lord has commanded. Paul alludes to the Lord’s command later recorded in Mt 10:10; Lk 10:7 (cf. 1Ti 5:18).

9:15 I have not used any of these rights. Philosophers emphasized being free from concern and free from depending on others; some also appealed to their financial independence to distinguish themselves from greedy charlatans. I would rather die. A common verbal contrast with a terrible situation, for both Jews and Gentiles.

9:16 I am compelled to preach. Stoics, the most popular philosophic sect in this period, believed that one could not evade Fate, so one should embrace it. More relevant for the personal God of the Bible: God’s call was not optional (cf. Ex 4:13–14). Woe to me. Those lamenting over a situation, both Jews and Gentiles, often cried in this way.

9:19 I am free. See notes on vv. 1, 12, 15. made myself a slave to everyone. Rhetoricians recommended adaptation for various audiences; some of the more moderate Pharisees also were ready to accommodate their hearers to bring them to love the Torah. By contrast, many aristocrats despised those who were too flexible as fickle demagogues who tried to please the masses; they sometimes dismissed such demagogues as “slaves.” Still, some valued being “slaves” or “pleasing” others if it maintained public order. Paul here serves an even greater purpose.

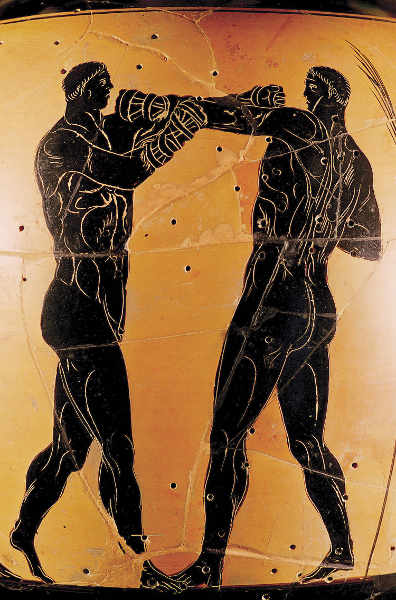

9:24 all the runners run. Runners and other athletes competing in the Greek games competed on behalf of their cities, following strict rules of training. the prize. A garland that would decompose over time. See the article “Athletic Imagery in 1 Corinthians 9.”

9:26–27 Paul describes the physical training athletes endured to seek a prize. See the article, “Athletic Imagery in 1 Corinthians 9.”

10:1–2 under the cloud . . . passed through the sea . . . baptized . . . in the cloud and in the sea. Jewish people looked back to the exodus as their corporate experience of redemption; Paul makes an analogy with salvation in Christ (cf. 5:7), including baptism (cf. 12:13).

10:3–4 spiritual food . . . spiritual drink. Access to spiritual food and drink did not prevent judgment in the past (vv. 8–10), so the present spiritual food and drink (vv. 16–17) would not protect those who committed the same sins (vv. 6, 11).

10:4 spiritual rock that accompanied them. Noticing that Israel drank from a rock in more than one place (Ex 17:6; Nu 20:8), Jewish tradition sometimes suggested that the rock followed them during their journeys. Some Jewish thinkers also compared the rock with personified Wisdom. Paul, who will soon (vv. 20, 22) quote from Dt 32, may think also of Dt 32:13, where God is Israel’s rock. Paul may use “spiritual” to offer an analogy (cf. Rev 11:8, where “figuratively” translates “spiritually”); or he may mean, “from the Spirit,” on which believers must depend. As a source of life, the rock corresponds to Christ.

10:6 examples. Speakers regularly exhorted people based on lessons from ancient examples; ancient historians recorded events partly for this purpose (cf. also Nu 16:38; 26:10). setting our hearts on evil things as they did. Despising manna, the spiritual food God provided (v. 3), Israel craved something else (Nu 11:4–6, 18, 20), and died (Nu 11:33).

10:7 idolaters. Jewish people generally regarded the worship of the golden calf, recalled here (Ex 32:4–6), as the most embarrassing incident in their history.

10:8 sexual immorality. When Midianite women seduced Israelite men for sexual immorality and then idolatry (Nu 25:1–8; 31:16), God judged Israel with a plague that killed 24,000 (Nu 25:9), probably Paul’s primary reference here. Paul’s slight numerical difference might also recall the three thousand who died in the immediate aftermath of the sin in v. 7 (Ex 32:28), followed by another plague (Ex 32:35).

10:9 We should not test Christ. Although God provided food (v. 3) and water (v. 4), Israel complained about these gifts and thus tested God (Ex 17:2, 7; Dt 6:16; Ps 78:18). killed by snakes. Complaints continued, and finally God sent snakes (Nu 21:5–6).

10:10 grumble. See note on v. 9. destroying angel. Lit. “destroyer”; see Ex 12:23.

10:14 flee from idolatry. Writers on moral topics frequently urged their hearers to run from vices (cf. 6:18). Sacrificial food was closely connected with idols (10:14–23).

10:15 judge for yourselves. Speakers often appealed to hearers in this way.

10:16 the cup of thanksgiving. A blessing over wine, thanking God, was normal before Jewish meals, including Passover (see note on 11:25). If the Passover practice in this period was the same as in our somewhat later documents about it, the Passover meal included four cups, as in Greek banquets.

10:17 one loaf. Jewish meals also included a blessing over bread. we, who are many, are one body. See note on 12:12.

10:18 those who eat . . . participate in the altar. All Israel shared in the Passover offerings (cf. 5:7); priests ate parts of most kinds of sacrifices (see note on 9:13). In antiquity, eating together established relationships, and sacrificial meat was connected with the deity to whom it was offered.

10:19 that an idol is anything. Paul agrees with Scripture (e.g., Isa 44:12–20) that idols are nothing themselves (cf. 1Co 8:4); but the demons that are associated with them (see note on v. 20) are the problem.

10:20 demons. The Septuagint, the pre-Christian Greek translation of the OT, sometimes renders idols or false gods as “demons” (Dt 32:17, partly quoted here and in Baruch 4:7; see also Ps 96:5; 106:37; Isa 65:3, 11). Most early Jewish and Christian sources regard the spirits that Gentiles worshiped as demons, as Paul does here.

10:21 the Lord’s table . . . table of demons. Ancient temples had tables for depositing offerings. The OT uses “the Lord’s table” similarly (Mal 1:7, 12), including for the place of the consecrated bread afterward eaten by the priests (Ex 25:30; 1Sa 21:6). Ancient invitations to dine at a temple often speak of the deity’s “table” (e.g., the “table of the lord Serapis”).

10:22 Continuing the context evoked in v. 20, Paul here uses the Greek version of Dt 32:21 (echoed also in Baruch 4:7). As in vv. 19, 23a, Paul may partly concede their objection, only to refute it afterward.

10:23 not everything is beneficial. See note on 6:12. Because others associated sacrificial meat with the demons behind the idols (vv. 28–29), one should abstain.

10:25 anything sold in the meat market. Sacrificial meat not used in the temple was sold in Corinth’s meat market, without being distinguished from other meat there not brought from this source. To avoid both sacrificial meat and meat that had not been butchered in a kosher manner (draining the blood), Jews in large cities normally had their own meat markets. Probably only people of means could normally afford to purchase meat.

10:26 The earth is the Lord’s. In reality, everything created belongs to God, not to other spirits. Although documented somewhat later, Jewish tradition associated the verse cited here (Ps 24:1) with blessing (thanking God for) meals.

10:27 If an unbeliever invites you to a meal. People invited friends and subordinate clients to banquets; to refuse would insult the host and provoke enmity. eat whatever is put before you. One was not obligated to eat all the kinds of food served at a banquet, though meat was expensive and valued.

10:28 do not eat it. Because sacrificial food was associated with sacrifices, a polytheistic friend would understand one’s willingness to eat explicitly sacrificed food as implied acceptance of sacrifice to the deities in question. (Jewish critics, who refused even to eat pork, would also be scandalized by fellow monotheists eating sacrificial food.)

10:30 with thankfulness. Jewish tradition included giving thanks before meals, a practice adopted by early Christians.

10:31 whether you eat or drink. God’s honor should control one’s choices even of food and drink at friends’ banquets (vv. 27–29). for the glory of God. Jewish teachers emphasized honoring God’s name; many philosophers also understood that eternal considerations should take priority over temporal ones.

10:32–11:1 Conclusions of works or, as here, sections within a work often included summarizing statements (cf. 9:19–23).

10:32 Do not cause anyone to stumble. Sacrificial meat could confuse Greeks and scandalize both Jews and some fellow Christians.

11:1 Follow my example. As in ch. 9, Paul appeals to his own example; other sages sometimes also did this, and disciples were expected to follow their teachers’ example.

11:2 Ancient writers often used digressions; the present one (vv. 2–16), digressing from matters of sacred food, is framed by Paul’s praise (v. 2) and lack of it (v. 17). I praise you for remembering me. Both letters and (more often) speeches could focus on praise or criticism. traditions just as I passed them on to you. Teachers often passed on traditions orally to disciples, expecting them to continue passing them on.

11:3, 4 head. Besides its literal sense of the top of one’s body (cf. vv. 4–6), “head” often signified a position of authority (cf. v. 3; others cite instances also for “source” or “prominent part”). Husbands did hold that role in ancient households, especially Greek and Roman ones. Paul might connect the wife dishonoring her physical head with bringing shame on her family. Ancient writers often argued based on wordplays, and the behavior of one family member was thought to reflect on one’s whole family. Romans covered their heads for worship but Greeks uncovered them.

11:5 woman who prays or prophesies. Although men normally held the most visible roles in ancient Israel, female prophets were respected (Ex 15:20; Jdg 4:4; 2Ki 22:14; Isa 8:3). Traditional Greeks often frowned on women speaking in the presence of men outside their families, but even they permitted women to speak by a deity’s inspiration.

11:6 she might as well have her hair cut off. Ancient Mediterranean men often viewed women’s hair as sexually appealing; shaving the head had the opposite effect and in that culture was humiliating for a woman (perhaps a factor in Dt 21:12–14). Writers sometimes reduced their opponents’ positions to the absurd by showing where they could lead if carried to an extreme.

11:7 A man . . . is the image and glory of God; but woman is the glory of man. Although some ancient Jewish texts (in contrast to others) spoke of only men as God’s image, both genders reflect God’s image in Ge 1:27 and (especially clearly) Ge 5:1–2. Paul may be emphasizing women’s derivation from man (see v. 8 and note).

11:8 woman from man. God formed the first woman from the rib of the first man in Ge 2:21–23.

11:9 woman for man. In Ge 2:21–23, God created woman because there was no “helper suitable” for the man (Ge 2:18; the Hebrew expression involves the man’s need and does not demean the woman).

11:10 the angels. Scholars propose various possible meanings. One proposal is that they refer to fallen angels attracted to human women (the most common ancient interpretation of Ge 6:1–2), although this interpretation might suggest the danger of conceiving giants (cf. Ge 6:4). Others, citing a similar idea in the Dead Sea Scrolls, suggest that the angels are simply angels present for worship, offended by immodest apparel. A further possibility is that Paul concisely evokes the angels mentioned earlier in his letter (6:3), implying that because these women will someday judge angels, they should use their authority (the same term translated “right” or “rights” in 8:9; 9:4–6, 12, 18) responsibly.

11:11–12 Some used arguments similar to vv. 8–9 to subordinate women harshly; Paul warns against extrapolating more from his argument than he intends.

11:12 woman came from man . . . man is born of woman. Everyone knew that men were born through women (Job 14:1; Gal 4:4), though the language here may echo especially the widely-read work 1 Esdras 4:15–17 in the Septuagint, the pre-Christian Greek translation of the OT. Those who argued mutuality of some sort were usually among those ancient writers friendlier toward women. from . . . of. These prepositions translate terms used for different forms of causation (see note on 8:6.)

11:13 Judge for yourselves. See note on 10:15.

11:14 very nature of things. Many people, and especially philosophers (notably the Stoics), made arguments from nature. Philosophers sometimes argued, e.g., that nature had given men beards to distinguish them from women, so that a shaved man was against nature (though clean-shavenness was the preferred style among honorable men in this region in this generation). if a man has long hair, it is a disgrace. Among others, ancient Greek heroes, whose statues abounded, and Biblical Nazirites (Nu 6:5) had long hair. Shorter hair was currently in fashion for men, however. Paul would know that peoples outside the empire, e.g., the feared Parthians to the east and Germans to the north, wore their hair very long, but arguments from “nature” were of various kinds, sometimes (as possibly here) from culture.

11:16 we have no other practice. Paul has offered various arguments, including from Scripture (vv. 7–9) and nature (vv. 14–15); now he appeals to consensus. Appeal to local or in-group custom was a common form of argument in antiquity. (Indeed, for one skeptical ancient intellectual group called the Skeptics, this was the only persuasive argument.)

11:17 I have no praise for you. Paul returns to the matter of sacred food after the digression in vv. 2–16. In contrast to the earlier discussion, the food discussed here is dedicated not to other gods but to the Lord. praise. Also in v. 22; see note on v. 2.

11:18 divisions. Might include the social divisions in v. 21. to some extent I believe it. Some scholars understand Paul’s statement here as mock astonishment, a rhetorical device used to drive home the inappropriateness of their behavior.

11:20 the Lord’s Supper. Cf. note on 10:21; here the phrase contrasts ironically with their own supper (11:21).

11:21 one person remains hungry. Some non-aristocrats may have been coming late from work as laborers or slaves (cf. v. 33), in contrast to the wealthier hosts who had leisure after their morning appointments. Alternatively, the hosts and any elite guests may want to eat their own high-quality food apart from the more modest meal being shared by the rest of the gathered believers. (This is true whether the guests bring their own food or the host supplies it; hosts were not expected to feed socially subordinate guests at their own social level.) another gets drunk. Although people regularly got drunk at banquets, ancient associations had rules for maintaining order at their community meals, barring quarrels. Scripture treated drunkenness as shameful (Pr 20:1; Ecc 10:17). For the contrast between Corinthians’ banquet expectations based on local practice and Passover-based expectations for the Lord’s Supper, see the article “Banquets in Corinth.”

11:23 received . . . passed on. Teachers and others who passed on traditions often used these words together (cf. v. 2). received from the Lord. This need not mean that Paul received this directly by revelation, since Jewish teachers often described their traditions as “received from Sinai”—by which they meant only that the traditions went back to Moses. on the night. As a Passover meal, the Last Supper occurred at night (Mk 14:16–18).

11:24 when he had given thanks. Jewish people gave thanks over bread and wine at the beginning of meals. This is my body. At the Passover, the bread was declared to be “the bread of affliction that our ancestors ate” when redeemed from Egypt. No one, of course, considered it literally the same bread from more than a millennium earlier; the point was that they were reenacting Passover, in some way sharing in the experience of their ancestors. As Passover commemorated God’s act of redeeming his people (Ex 12:14; 13:3; Dt 16:2–3), so the Lord’s Supper commemorates Jesus’ act of redemption (cf. 1Co 5:7). Cf. Lk 22:19 and note.

11:25 This cup is the new covenant in my blood. See note on v. 24. Jesus’ language evokes the blood of the covenant at Sinai (Ex 24:8), but plainly as part of a new covenant (cf. Lk 22:20 and note), promised in Jer 31:31. Cf. Mt 26:27–28 and notes. Because the cup is after supper, it could match the third or possibly fourth cup of the Passover meal (cups divided the banquet into phases). Greeks often had a drinking party with entertainment (or sometimes discussion or lectures) after the meal; for early believers, this may have been the time instead for Scripture exposition. (Pharisees and some other pious Jews insisted that the Torah be the main topic of conversation even during the meal; cf. Dt 6:7; Ps 1:2.)

11:26 until he comes. When Jewish people commemorated the Passover, they often also contemplated their future redemption. Many also anticipated an end-time banquet for the righteous (cf. Isa 25:6), which Jesus at the Last Supper also promised (Mk 14:25).

11:27–29 unworthy manner . . . without discerning the body of Christ. By treating those of lower worldly status as of lesser worth (vv. 21–22), believers in Corinth failed to discern Christ’s body in one another (cf. 10:17), and thus demeaned the commemoration of Jesus’ sacrificed body.

11:30 weak and sick. Possibly Paul implies that demeaning members of Christ’s body (see previous note) also inhibits corporate gifts of healings (12:9). asleep. A standard euphemism for “dead.”

11:32 so that we will not be finally condemned with the world. Jewish teachers often emphasized that the righteous suffer in this life to atone for their few sins, whereas the wicked will be tormented in the world to come for their many sins. For Paul, suffering may be a means not of atonement (cf. 1:30; 5:7; 6:11) but of bringing repentance (cf. 5:5).

11:34 eat something at home. The urban poor often had limited access to food and cooking in their small rooms; some people cooked on charcoal braziers, but people often ate at cheap neighborhood taverns. Those with more means could eat in their homes before the church gathered. further directions. Letters often promised further instructions when the writer would come; speaking face to face was preferred (e.g., 3Jn 10, 14).

12:1 Now about. Sometimes used by ancient writers (and in the Greek text of 7:1, 25; 8:1; 16:1, 12) to transition to a new subject.

12:2 mute idols. Idols were unable to speak (e.g., Ps 115:5); possibly Paul alludes here also to Greek oracles, where priests or priestesses might speak for a deity. Paul is for prophecy (14:1)—so long as it comes from the true Spirit that honors Jesus (v. 3).

12:4–6 There are different kinds of . . . different kinds of . . . different kinds of. Beginning new clauses the same way is called anaphora. Spirit . . . Lord . . . God. Like a good orator, Paul emphasizes his point here by repeating it in three parallel ways (in this case including the Spirit, Jesus and God the Father).

12:6 same God at work. God gets the credit for all the gifts, so no one can boast over their gift versus another’s.

12:7 Speakers sometimes emphasized a matter by bracketing it; v. 7 and v. 11 together reinforce the dependence on God’s Spirit to empower the activities in vv. 8–10.

12:8–10 Ancient orators liked to use lists (as also in vv. 28–30; 14:26), as well as repetition (here, “to another” seven times, most of them the same Greek term).

12:8 message of wisdom . . . message of knowledge. Corinthian culture valued speaking (in rhetoric), wisdom (in philosophy) and knowledge.

12:9 gifts of healing. Gentiles in Corinth could seek healing at local shrines (especially that of Asclepius), but the Spirit provided healing gifts from the true God among the believers.

12:10 prophecy. Prophecy was familiar from the OT (the most common ministry of speaking God’s message noted there). tongues. Speaking in tongues began at Pentecost, and unlike prophecy, lacked significant pagan parallels at the time.

12:12 a body, though one, has many parts. Earlier Greek and Roman thinkers had compared the state and even the universe to a body of interdependent members. Often ancient writers used the analogy to support hierarchy, but Paul here values the importance of the diverse functions represented. Speakers also would elaborate an important point; Paul elaborates the point here in vv. 12–27; vv. 12, 27 together identify the theme of the section they frame.

12:13 baptized by one Spirit. Gentiles who converted to Judaism were immersed in water and Christians had adopted and developed baptism also as a public act of conversion. Most important, however, Christians recognize that God’s own Spirit initiates us into this new relationship with God and one another (cf. the promise in Eze 36:25–27). the one Spirit to drink. Jewish sources speak of drinking from divine Wisdom, but see especially 10:4 and note.

12:14 not made up of one part but of many. Speakers sometimes emphasized a matter by bracketing it; v. 14 and v. 20 together stress the value of all the members in the one body in vv. 15–19.

12:15–16 if the foot should say . . . if the ear should say. One rhetorical device often used by ancient orators to hold attention was personifying impersonal objects so that they could speak.

12:17–19 Rhetorical questions in a series drive home a point. Orators also sometimes would dwell on a point, reiterating it in various ways to drive it home, as in Paul’s repeated emphasis throughout this section on the one body with many members.

12:21 The eye cannot say . . . the head cannot say. See note on vv. 15–16. The absurdity of eyes or hands independently speaking reinforce in a graphic, humorous manner the point of our members’ interdependence.

12:23 parts that are unpresentable. May be the genitals and excretory organs, which people normally covered in public. Exceptions to such coverings included Greek athletics, conventional settings such as public baths and public toilets, and shameful settings such as victims being executed.

12:24 giving greater honor. Paul’s use of honor and power language may subvert a common ancient use of the body analogy to support hierarchy.

12:28 Orators liked to use lists (see vv. 8–10, 29–30). first of all. Numbered examples were usually ranked, although other elements that were not numbered could be randomly arranged.

12:31 desire the greater gifts. Speakers sometimes framed a digression with a related thought; desiring the most helpful gifts here and in 14:1 frame a discussion of the gifts and love in ch. 13.

13:1–13 Sometimes ancient orators would praise a virtue at length, using exalted prose. Early Christians could elaborate in similar ways on faith (Heb 11) and love (here in ch. 13). Paul’s praise of love here is not, however, merely theoretical; it directly challenges the behavior of many of the Corinthian Christians, who are boastful and proud (e.g., compare v. 4 with 3:21; 4:7; 5:2, 6).

13:1 If I . . . but do not have love. Orators often repeated a phrase (vv. 1–3) to emphasize a point emotionally. tongues . . . of angels. Scholars debate whether Paul implies special angelic languages (which some evidence suggests that some ancient Jews may have believed in) or simply uses hyperbole. gong. The Greek term indicates an object made of bronze, a metal for which Corinth was well known (although scholars often suggest that not all Corinthian bronze was made in Corinth, and some of what circulated under that label may have even been counterfeit).

13:2 faith that can move mountains. Cf. Mk 11:23; moving mountains was apparently an ancient figure of speech, also attested in some Jewish sources, for doing what was virtually impossible.

13:4–8a Orators would sometimes develop a point at particular length, here the characteristics of love. Clever repetition of sounds also could sustain attention; every word in v. 4 ends with a vowel sound (the two most common ending sounds here are–ei and–ai). Three consonantal endings in v. 5 are the only exceptions to vowel-sound endings through v. 8a.

13:8b–13 Valuable as God’s present gifts are, they are less permanent, and therefore from a Greek perspective less valuable, than eternal virtues.

13:8b where there are. A good preacher, Paul three times repeats this phrase; such opening repetition is anaphora, an ancient rhetorical device that drives home a point and sounds pleasant.

13:9 prophesy in part. Prophetic insight, like other knowledge, is often quite limited; see, e.g., 2Sa 7:3–5; 2Ki 2:3, 5, 16–18; 4:27; Lk 7:19; Ac 21:4.

13:11 When I became a man. Around age 13 (at least in later Jewish tradition) or around age 16 (more often for Romans), boys would enter manhood; at that time a Roman boy would replace his childhood toga for an all-white adult toga.

13:12 reflection as in a mirror. Many mirrors were made from bronze, including Corinthian bronze (see note on v. 1), but ancient mirrors offered reflections much less clear than direct sight. face to face. Moses saw God “face to face,” unlike other prophets (Nu 12:6–8, especially in the Greek version; Dt 34:10), though even he could not see God’s glory fully at that time (Ex 33:20). know fully. Jeremiah had announced a time when all God’s people would know him (Jer 31:33–34).

13:13 greatest of these is love. Ancient writers sometimes repeated a point at the beginning and end of a topic, as with love’s eternality in v. 8 and here. Ancient thinkers varied in their views of the chief virtue, but Jesus’ teaching united his followers around love (Mk 12:29–31).

14:2 anyone who speaks in a tongue. Although many ancient peoples claimed to have prophets, speaking in tongues may have been unique to early Christians. Supposed ancient parallels were usually simply a matter of priests editing already basically intelligible speech into a more coherent and eloquent form. mysteries. Highly valued—especially when interpreted (cf. Da 2:28–29, 47).

14:3 for their strengthening, encouraging and comfort. As in the OT, prophecy could include strengthening (building up, as in Jer 1:10), encouraging and comfort (cf. Isa 40:1). That Paul omits specific mention of messages about judgment, despite their frequency in earlier Scripture, may be because he expects this to be less relevant for churches (though cf., e.g., 11:30; Rev 2:5, 16).

14:5 I would like every one of you. Moses also wanted all God’s people to prophesy (Nu 11:29), and Joel promised that God would empower all his people in this way (Joel 2:28). Although some individuals might remain characteristically prophets in contrast to others (1Co 12:28–29), the outpouring at Pentecost democratized prophetically-guided speaking for God far beyond the models in ancient Israel.

14:7–8 Although musical instruments lack language, they could communicate meaning; e.g., flute melodies could give instructions to flocks, and trumpets regularly signaled armies (see note on v. 8).

14:7 pipe. A wind instrument that sounded like an oboe; common in religious and emotional music, it often had two pipes from the mouthpiece. harp. A stringed instrument that often accompanied singing; people regarded it as particularly harmonious.

14:8 trumpet. Used to summon troops for battle, to march and so forth; an uncertain trumpeting would confuse the soldiers.

14:11 foreigner. Translates a Greek term by which Greeks often designated those who did not speak Greek.

14:13–15 Many Greeks and some Diaspora Jews believed that prophetic inspiration temporarily possessed and displaced the mind. Paul seems to disagree regarding prophecy (v. 32), and believes that the mind can be used (through interpretation) even in connection with tongues, though tongues appear to focus more on the affective than the cognitive dimension of the human personality. Some in ancient Israel experienced inspired (prophetically guided) worship (e.g., 1Sa 10:5; 1Ch 25:1–3); it became more pervasive in Jesus’ movement (cf. Jn 4:24; Eph 5:18–19; Php 3:3).

14:16 say “Amen.” Jewish prayers typically concluded with “Amen,” already used by ancient Israelites to express affirmation (e.g., Ps 41:13; 72:19; 106:48).

14:19 ten thousand. The largest Greek number, often thus used hyperbolically.

14:20 stop thinking like children. Referring to adults’ immaturity in important matters demeaned them (see notes on v. 21; 3:1).

14:21 other tongues. In Isa 28, God warns that because Israel acts like immature children (see note on v. 20), refusing to understand his message (Isa 28:9–10), God will speak to them instead by judgment through the unintelligible Assyrians (Isa 28:11).

14:22–25 In light of the quotation in v. 21, the point in v. 22 might be that one of the functions of tongues was to signify that judgment was coming on the disobedient. Some others suppose that Paul cites a Corinthian idea in v. 22 and then refutes it in vv. 23–25. Still others suggest that the point in vv. 23–25 is that tongues can confirm unbelievers and prophecy can invite them to be believers. Or possibly vv. 23–25 shows that even when the situation of v. 22 is reversed, prophecy is more valuable.

14:23 inquirers or unbelievers come in. Hosts and members could invite unbelieving friends to the house gatherings. out of your mind. Ancient Mediterranean people were familiar with prophecy but not tongues, which lacked close parallels in antiquity. Greeks often were impressed with prophetic madness that would make inspired people out of their mind (this was more common and more relevant to the idea of inspired frenzy than the group frenzy of certain cults proposed by a minority of scholars here).

14:25 secrets of their hearts are laid bare. Accurate revealing of their hearts’ secrets (an eschatological foretaste; cf. 4:5; Ro 2:16), however, would lead to repentance. fall down and worship. Outsiders bowing and acknowledging God probably recalls Isa 45:14.

14:26–40 That Paul offers these regulations suggests that he had not provided them earlier during his lengthy stay (Ac 18:11, 18). These regulations, then, are probably directed toward a situation of abuses. We also should keep in mind that they applied to house churches, which probably rarely could accommodate 50 or more members. Although principles of order would remain, specifics might differ for larger congregations that could not accommodate all the ministries of v. 26 within one service, and for smaller groups meeting for private prayer without possible unbelievers present.

14:26 come together. Synagogues in this period were Jewish community centers used most fully for prayer and corporate study of the Torah on the Sabbath. Many may have been much less formal and allowed wider participation than in a later period. hymn. Lit. “psalm”; Jewish people used Biblical and sometimes post-Biblical psalms. By contrast, for anyone to bring a “revelation” or be inspired to speak in a “tongue” they did not know was unlike virtually all other assemblies in antiquity.

14:27 one at a time. Ancient assemblies varied in their emphasis on order (those in the Dead Sea Scrolls required strict order), but order would be lost anywhere if multiple persons tried to speak at once. Paul disagrees with the Greek view that inspired speech was uncontrollable (v. 32).

14:29 others should weigh carefully what is said. In ancient Israel, many junior prophets probably learned especially in small groups under the mentorship of more experienced prophets (cf. 1Sa 19:20; 2Ki 2:3–7, 15; 6:1–7). Most first-generation churches lacked such prophetic mentors, so fellow junior prophets in the congregations would have to help evaluate the extent to which their peers were hearing the Spirit accurately. For the limitations of prophecy, see notes on 13:9; Ac 21:4.

14:30 someone who is sitting down. In Diaspora assemblies, one would stand to speak.

14:31 you can all prophesy in turn. Paul here depicts house churches more like a school of the prophets (cf. 1Sa 19:20, though Paul requires more order) than like ancient synagogues or other meetings of ancient associations. See the article “Prophecy in Antiquity,” see also note on v. 5.